Race

Introduction

Since its inception, Dialogue has bravely entered conversations and cultural moments with integrity, hope, and charity and this is true with the issues surrounding race.

The Church has engaged in ongoing dialogue about its racial history and has taken steps to address the legacy of its past teachings. This includes essays published on the official Church website that address controversial historical issues, including race. While significant progress has been made, there are still challenges and discussions surrounding race within the LDS community. Some individuals and groups continue to grapple with the legacy of past policies and how they are understood and interpreted today.

Exploring this curated topic might provide valuable insights into the historical and contemporary discussions surrounding race within the Mormon community, as well as the efforts being made to address and understand these issues. It could include articles, essays, interviews, and other resources that contribute to a more informed and nuanced understanding of race within the context of Mormonism.

Dialogue Topic Podcasts: Race

Featured Issues

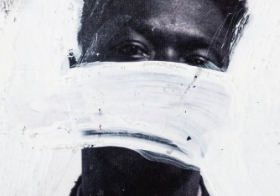

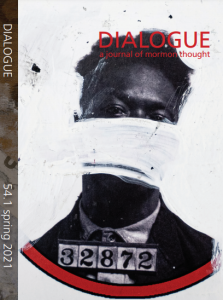

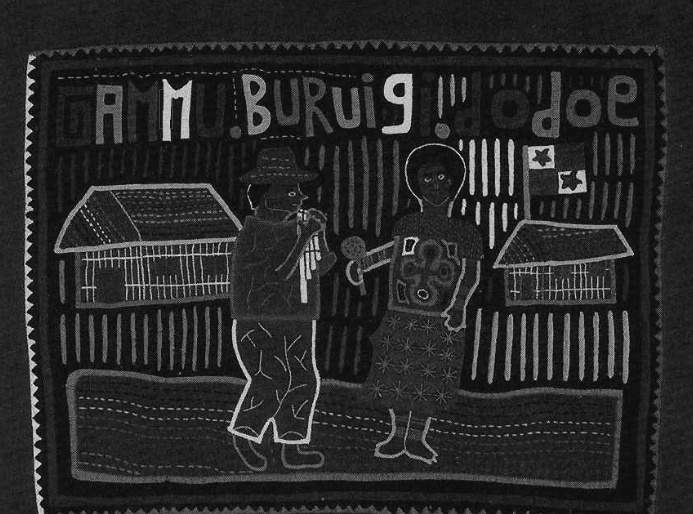

Spring 2021: The Spring 2021 Issue startles the viewer with it’s powerful cover by Marlena Marie Wilding that Darron T. Smith then unpacks with his Art Note: The Mask We Must Wear in a Racist Society: Reflections of Black Suffering in the LDS Church Through Art. The issue also includes an incredible Roundtable on White Supremacy in Mormonism.

Fall 2019 Issue: The Fall 2019 Issue includes an important panel of students of color and then another roundtable looking at the change of the name of the church. Some of the offerings include James C. Jones, “Racism”; Margaret Olson Hemming and Fatimah Salleh, “Wrestling with Racism in the Book of Mormon”; and Rebecca de Schweinitz, “There Is No Equality: William E. Berrett, BYU, and Healing the Wounds of Racism in the Latter-day Saint Past and Present.”

Fall 2018 Issue: The Fall issue commemorates the lifting of the priesthood ban and in true Dialogue style, scholars discuss and dissect it’s implications esp. Lester Bush, “Looking Back, Looking Forward: Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine Forty Five Years Later”; Darron T. Smith, “Negotiating Black Self-Hate within the LDS Church”; Joanna Brooks, “The Possessive investment in Rightness: White Supremacy and the Mormon Movement”; and Matthew Harris, “Mormons and Lineage: The Complicated History of Blacks and Patriarchal Blessings, 1830-2018.”

Spring 1973 Issue, especially Lester E. Bush, Jr. “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview,” and the responses to Bush’s article.

Curated Articles

How a Mormon Ended Up at Union Theological Seminary: A Step Toward Racial Justice and a Better Church

James C. Jones

Dialogue 56.1 (Spring 2023): 7–50

In the decade since I made that decision, a lot has happened that ultimately reoriented me back to the academy and to theological studies in particular. First, the job I took after graduating from Brigham Young University took me to Boston, Massachusetts. I immediately noticed a refreshing difference between the congregations I attended in Utah and congregations in Boston. These were the most educated people I had ever worshiped with in my adult life, and it was the safest I had ever felt being my authentic self at church.

Listen to the audio version of this essay here.

Four years ago, I was living my best life as a touring a cappella singer. The sum of my ambition was to make great and meaningful art and create the first a cappella group to play the Superbowl halftime show. For years, a photo of the colorfully lit MetLife stadium was my lock screen as a gentle and constant reminder of that goal. Today, I have just finished my first year of graduate school studying Black liberation theology in hopes to create a more complete and enriching Mormon theology that validates marginalized folks and, by extension, creates a space that is more in line with the integrated and diversified New Testament church that Christ intended. As much as I love the restored gospel and the Church, this is the last place I saw myself.

I used to clown returned missionaries who couldn’t seem to let go of their missions. They would continue to dress like missionaries weeks after their return, talk endlessly about their missions, and pursue academic tracks that led to working in Church education. In retrospect, I see that loving the Church, the gospel, and the scriptures so much that you want that to be your vocation isn’t the worst thing, but, at the time, it read like fanaticism to me. I loved the scriptures and the gospel too, but I felt my ministry lay in a different academic path and aggressively acted accordingly.

Time would tell me, however, that my ministry wasn’t in the academy at all—at least for this season of my life. I wasn’t a great student, and school stressed me out. As I prepared for graduation, I got rejected by every program I had hoped would improve my odds of advancing my academic and professional career, including the only grad school to which I applied. When Teach For America rejected me a second time, my ego had had enough and I forsook academia for the arts with no intention to return.

In the decade since I made that decision, a lot has happened that ultimately reoriented me back to the academy and to theological studies in particular. First, the job I took after graduating from Brigham Young University took me to Boston, Massachusetts. I immediately noticed a refreshing difference between the congregations I attended in Utah and congregations in Boston. These were the most educated people I had ever worshiped with in my adult life, and it was the safest I had ever felt being my authentic self at church. Some of the Saints had also organized local events to have Latter-day Saint scholars, thinkers, influencers, and leaders share their expertise, experience, and testimonies. The first event I attended like this featured a discussion on womanist theology by a Harvard- and Howard-educated Black Latter-day Saint scholar. I could not have gotten that anywhere else in the world.

Second, the murders of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown happened. They weren’t the first unarmed Black men to be gunned down by the police or white vigilantes, but they were the first high-profile cases in the age of social media. They were for millennials what Rodney King was for Gen Xers. Their deaths were catalysts to what would become the rallying affirmation and organization #BlackLivesMatter, in addition to other civil rights organizations. Everyone had an opinion. The most troubling ones to me were, regrettably, from members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—people I had considered friends, people I’ve prayed and preached the gospel with. The callous response to Black pain—my pain, my family’s pain, my community’s pain—was inexcusable for any of the Saints. To make matters worse, going to church was not the balm of Gilead it should’ve been for Black members. Most of the time our pain was ignored, and if it was mentioned at all, it was straight up minimized. There was no mourning with those who mourn or comforting those who stand in need of comfort. When I went to interfaith vigils to mourn properly, I was almost always the only Latter-day Saint present. I would not accept that this was the best the Church could do in the face of racism and Black pain—not the restored Church of the same Christ who was literally lynched by the state for threatening corrupt political systems that oppressed the marginalized.

Third, the exclusion policy of November 2015 happened. For many of the Saints, including myself, this was something of a crisis. Somewhere at the intersection of my close associations with queer people, my inability to theologically and rationally justify such a policy, and my disdain for bullying and discriminatory behavior, I had to confront queer pain and my faith and figure out how to reconcile the two. Ultimately, the question wasn’t how to reconcile my faith and queer pain—our theology already validated queer life when I honestly looked at it. What I needed to come to terms with was what that knowledge requires of me as a person of faith. Peace would not come if I didn’t hold our institutions accountable to the Christ we read about in the scriptures, and that meant challenging policy that denied the imago dei in our queer siblings, that denied all were alike unto God, and that denied God was no respecter of persons. Anything less would be cowardice and dishonesty on my part. I wasn’t alone in my feelings, and this would become palpable in the coming years.

Fourth, in 2019, during the second annual Black LDS Legacy Conference, I felt prompted to create a space to keep conversations going similar to those at the conference. Black folk were able to talk about the gospel in a way that centered Blackness—a way that honored our pain while seeing our strength and, wherever possible, using the restored gospel as a tool to do as much. The conference was a liberating experience. As a Black Latter-day Saint, I’m used to at least one of those identities constantly being scrutinized anywhere I go. But at that event, my body is able to release much of the tension it holds. I don’t have to explain my existence to anyone in that space. I am not a guest. I am home. I wanted to create something close to that for myself and others who struggle to fit in because they look different, love differently, think differently, or otherwise have different needs. They too deserve to be in a space where they feel home.

This desire ultimately gave birth to what is now Beyond the Block, a podcast I’ve been running for a few years with the goal of centering the marginalized in Mormonism. The podcast discusses the Come, Follow Me lesson each week while prioritizing a reading for the marginalized. My co-host, Derek Knox, a queer theologian and friend, seemed the perfect conversation partner as pretty much every time we got together, our conversations would turn into a Beyond the Block episode. The show has a modest but loyal following. As of this writing, there hasn’t been a congregation I’ve visited in the United States where there wasn’t someone familiar with the show. The day after my records were transferred to my ward in New York, I was tapped to substitute teach seminary because of the work I had done on Beyond the Block. It is validating to know that something that heals my soul also helps others too, gives them voice, empowers them to affirm the least of these, and helps them be more enriched by our faith.

The show’s popularity gave me opportunity to speak at several events and to several publications. People thought our ideas were equal parts life-giving and provocative, though we didn’t feel we were saying anything particularly radical in terms of the scope of our sacred texts. That was the point, though. We already have the tools to affirm people on the margins and we don’t have to read too closely or too much to find them. All we need is a different lens, and that can be difficult to find when our institution is overwhelmingly white and we’re all taught the same scriptures the same ways by the same presumably straight cis white dudes born in the Jim Crow era.

Bear in mind: though I knew I was doing important work, it’s work I was doing on the side. I had and still have no professional ambitions where theology and religion are concerned. But the Church and the United States’ political climate demands more of the Church. People my age and younger were becoming increasingly disaffected with it, feeling it had nothing relevant to contribute to our lives or to the most urgent and important matters we faced. The Church was troublingly silent on issues of race, despite having a rich theology from which to create solutions, and it still refuses to engage any real interrogation of policies that alienate queer people or keep women, who represent close to three times the active membership of men, relegated to marginal positions of power and leadership. I believe all of this is a stumbling block to our retention and missionary efforts among the least of these, those with the most to teach us about Christ, and that frustrated me. Side hustle or not, I wanted to put myself in the best position I could to address these problems. With my new influence and opportunities, it quickly occurred to me that I’m still a relative amateur in the world of theology, yet when people want to talk race, theology, and Mormonism, I’m one of the folks consistently getting called and, frankly, I feel underqualified. I regularly studied and prepared as thoroughly as I could for every engagement I did, but I felt keenly that something was missing from my learning experiences.

As a final point, a week after the same 2019 Black LDS Legacy Conference that inspired the podcast, I was invited to give a talk on racism at church (now published in the Fall 2019 issue of Dialogue). Perhaps because I sourced the scriptures liberally, multiple members of the congregation suggested looking at divinity schools. I received the compliment but heartily laughed at the suggestion. I had a job. I hated school. I didn’t think I was suited for the academy (and still don’t). And what was a degree in theology going to do for me professionally? It was bad enough my undergrad degree was pretty useless; I didn’t want an advanced degree that was also useless. As time went on, however, the need for better theological education, especially in our church, became more apparent. With rising racial tensions in the United States, I was getting busier. At church and on my own, I didn’t feel I was gaining the tools needed to study scriptures more intelligently and imaginatively, nor did I feel I was gaining the tools to more critically engage my faith in the public square. My education likely wouldn’t progress if I didn’t intentionally create more time for it and use the best tools available, including academic institutions.

By summer 2020, I was at least open enough to the idea of divinity school that I decided to apply to some just to see what would happen. Around that same time, my elders quorum president led me through a discernment process that helped clarify my goals and the role the divine had in them. The November night I sent off my first three applications, I knew I was getting in, and I felt good about that. Sure enough, I got my first acceptance letters a few months later and was not just relieved but energized. The news felt good, and it felt right. Whatever I was to do with my future, the Spirit seemed to confirm that divinity school was going to better prepare me for it.

I applied to another institution primarily for its prestige. I didn’t feel anything pushing me toward the school, but it was a stone’s throw from my home, somewhat familiar, I potentially had a connection there, and it is pretty popular for Latter-day Saints who do venture into theological studies. It also housed Cornel West, one of the most provocative and brilliant thinkers in philosophy, politics, and theology, and I didn’t want to pass on the opportunity to work with such an influential Black figure. I even gave him a whole paragraph in one of my application essays. I was rejected. In a twist of fate, though, he had a very public falling-out with the university and was taking his talents to Union Theological Seminary, the school where he had begun his teaching career. At this point, I hadn’t yet considered Union, but it actually made perfect sense. The most frequently referenced school in the biographies of the theologians I read was Union. My theological idol and the creator of Black liberation theology, James Cone, had spent most of his career there, and one of his most notable students, The Very Reverend Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, one of the founders of womanist theology known for her trailblazing work addressing sexuality and homophobia in the Black church, is a professor and dean there. Further, social justice isn’t just an elective subject there but baked into the school’s culture and curriculum itself. In short, Union Theological Seminary seemed to be the institutional expression of my Black Christian prophetic identity. Gaining access to all the resources of Columbia’s various schools as well as getting to live in New York wasn’t a bad benefit either. I accepted their scholarship offer the following month. Serendipitously, Dr. West isn’t just my teacher but my advisor as well.

Since being here, my faith hasn’t come up much—at least not as something to be scrutinized. In my first meeting with Dr. West, he told me of one of his first encounters with Mormonism was being part of the first expanded crop of Black Harvard recruits in 1970. The relatively new dean of admissions who facilitated the influx was Chase N. Peterson, a Latter-day Saint. In that light, the idea that I wanted to create a more inclusive and liberating theology didn’t seem all that foreign to him. The other Black seminarians have been curious about my membership as I’m the only Black Mormon most of them know, but they seem to care less about my religious affiliation and more about how that affiliation moves me to show up for others. How does our theology liberate Black people? What does it offer those without an address? What does it say to us about our responsibility to the poor and the exploited? How does it help us break generational curses? How committed is it to the resistance of oppression? These are all great questions that I hope to refine our answers to during my time here.

I’m the only Latter-day Saint at this school and, to my knowledge, the only one ever to pursue a degree from here. That’s not an accident. Besides Latter-day Saint leaders not being required to obtain a theological education, places like Union that prioritize affirming theologies (Black liberation theology, queer theology, womanist theology, et al.) don’t attract members of a church that doesn’t do the same. We’re not really conditioned to, and that’s tragic. The Church’s decision to adopt American standards of respectability has moved us away from our radical, groundbreaking, and affirming roots. Specifically, the infections of white supremacy and patriarchy have compromised our movement and blurred the lens through which we view our text and our theology. It’s not a coincidence that the majority of our significant revelations came in the early days of the Church and that we haven’t had one since the lifting of the priesthood and temple restrictions in 1978. It’s not an accident that we’re consistently one of the later churches to condemn racism nor is it an accident that Black, queer, and other marginalized groups are consistently underrepresented in Latter-day Saint congregations, let alone Church leadership. I live in Harlem, a famously Black neighborhood, yet it’s not an accident that the Harlem congregation is only about 20 percent Black on its best Sundays. Only hours ago, I returned home from a Sunday School lesson in my mother’s ward on Official Declaration 2 with no Black people present but my mother and me. In my estimation, these realities are unacceptable for the restored Church of the same Christ who lived and operated in the margins.

If I am to help change these realities, I have to know what I’m talking about and what I’m doing. I have to know the scriptures and our history better than those who would use the same to discriminate or cause harm. I also have to venture outside of Sunday School, elders quorum, the Church Educational System, and other Mormon-centric spaces to learn other ways to read sacred text and perhaps, most importantly, to understand the role of theology in the world today and how to practically implement that in justice efforts in and out of the Church.

There will be and already has been resistance to these efforts. Ever since Beyond the Block gained steam, many have taken offense that I would suggest bigotry exists in the Church, that some of our policies are scripturally unjustifiable, or that the brethren don’t know everything and can act in ways that do active harm. I was slated to be the creator of the Church’s first anti-racist online course via their publishing company. My public criticism of a living Church leader’s prejudice, however, kept them from publishing it, even though my course, they said, was likely to be the most popular one they ran. The irony of being hired to teach others to fight prejudice and then being fired for calling out prejudice was not lost on me. I’ve made peace with the idea that operating strictly within the Church’s institutional parameters—an institution where there is no real way for members to seek redress for policies that harm others and where there is punishment for simply being critical of leaders—is likely not going to be the way the necessary changes come about.

However, something I’m still making peace with is the fact that I even need to be here. This work is primarily a labor of love; I’m grateful to be in a position to do it, and I feel closer to the divine than I’ve ever been when I use God’s words to affirm the least of these, even when there is a social and emotional cost to it. There is, however, a tinge of resentment at being in this position. Activism, let alone theologically informed activism, was not my Plan A. I don’t believe it’s anyone’s. I had a whole career that brought me immense joy prior to entering grad school. This is exhausting work. I don’t feel the academy suits me, and learning disability, processing disorders, inexperience, and neurodivergence aggravate this experience. I don’t particularly enjoy the study of theology, though I recognize its importance and how life-giving it can be. What I resent is that I feel that my entire existence in this space—a space that I neither love nor feel equipped to be in—is a response to bigoted idolatry within my faith community, who should know better as disciples of Christ. I should not be here. No one should be. No one should spend any part of their existence defending it because of their race, gender, orientation, ability, socioeconomic status, or other identities. I’d like to believe, however, that that resentment is an appropriate tribute to and evidence of my love for and commitment to the marginalized. I’m still learning to navigate this tension with love. At the end of the day, all I want to be is a sharper instrument of the Lord’s peace, and I have come to the conclusion that I can’t do that if all my education comes from the same people teaching the same things, none of which seem to be adequate to address many of the world’s and my own most urgent and important issues. One of the reasons I started Beyond the Block was to create a space to facilitate the discussions I feel we need to have as a church but aren’t having. With a graduate education in theological studies, I’m hoping to be better at that work so that others in and out of the Church may see what those like me see in our theology and, eventually, build and mobilize a culture that shifts us more in line with the New Testament church of Christ and away from the idols of patriarchy and white supremacy. Further, if I actually manage to create a new field of study, I’ll be able to help ensure that this work, which stands on the shoulders of the great Black individuals like Cathy Stokes, Darius Gray, and many others, will be further legitimized, grow, and continue long after I’m gone. My decision to go to school, in short, is simply my best effort to help build Zion.

[post_title] => How a Mormon Ended Up at Union Theological Seminary: A Step Toward Racial Justice and a Better Church [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 56.1 (Spring 2023): 7–50In the decade since I made that decision, a lot has happened that ultimately reoriented me back to the academy and to theological studies in particular. First, the job I took after graduating from Brigham Young University took me to Boston, Massachusetts. I immediately noticed a refreshing difference between the congregations I attended in Utah and congregations in Boston. These were the most educated people I had ever worshiped with in my adult life, and it was the safest I had ever felt being my authentic self at church. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => how-a-mormon-ended-up-at-union-theological-seminary-a-step-toward-racial-justice-and-a-better-church [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2024-03-18 14:26:09 [post_modified_gmt] => 2024-03-18 14:26:09 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=32229 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Joseph Fielding Smith’s Evolving Views on Race: The Odyssey of a Mormon Apostle-President

Matthew Harris

Dialogue 53.3 (Fall 2021): 1–76

Given the inadequate tools to police racial boundaries, LDS Church leaders like Joseph Fielding Smith struggled to define precisely where Black and light-skinned Latter-day Saints fit into the Church’s conception of soteriology.

Listen to the Out Loud Interview about this article here.

In 1963, Joseph Henderson, a non-Mormon from New York, wrote a pointed letter to LDS Church apostle Joseph Fielding Smith asking him about the racial teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[1] The letter triggered a sharp response from Smith, who informed his interrogator that he was “getting a little fed up on the idea that so many people think I am responsible for the Negro not holding the priesthood.”[2] It is easy to see why Henderson held Smith responsible for the Mormon priesthood ban, which also restricted Black people from temple access. The apostle had authored several books defending the ban and he was the Church’s most aggressive leader condemning Mormon intellectuals who criticized it. Smith saw himself as the guardian of Mormon orthodoxy, not just on matters of race and lineage but also on issues like evolution and doctrinal exegesis.[3] Yet over the course of Smith’s long ministry, and especially during the last decade of his life, he began to envision a more inclusive LDS Church for persons of African ancestry. He took dramatic steps to both convert and retain Black Latter-day Saints. It was less a change in how Smith read scripture and more about the turbulent times in which he lived. The civil rights movement—and more critically Smith’s own awareness of how the priesthood and temple ban affected Black members—convinced him to reimagine a place for them within the Church.

***

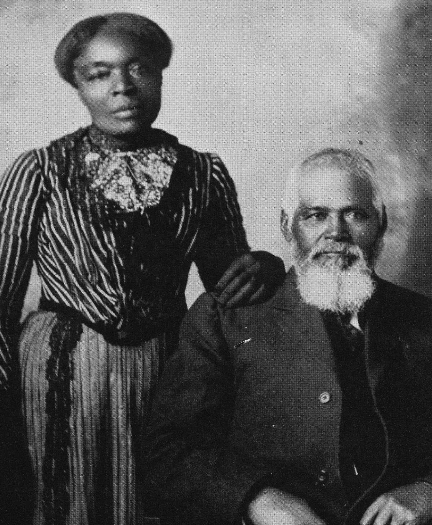

Born in 1876 in what was then the Utah Territory, Joseph Fielding Smith came from royal Mormon stock. He was the grandnephew of Mormon founder Joseph Smith, grandson of high-ranking Church leader Hyrum Smith, son of apostle and Church president Joseph F. Smith, and cousin, brother, or relative to several other apostles, including leaders in the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (today the Community of Christ). He was unique in that he spent virtually all of his adult life in the highest councils of the LDS Church. Though he lacked formal training in higher education, Joseph Fielding Smith was one of the Church’s most prolific writers in the twentieth century, authoring scores of books and articles that, as two recent writers explained, “helped educate generations of Latter-day Saints about the history and doctrine of the Church.”[4]

Called as an apostle in 1910 at the age of thirty-four, Smith served in a number of capacities in the Church, including Assistant Church Historian, Church Historian, president of the Genealogical Society, president of the Salt Lake Temple, president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, First Presidency counselor, and Church president.[5] Like many Latter-day Saints, Smith received a patriarchal blessing—a special bestowment by an LDS Church patriarch—that guided his life and shaped his ministry.[6] He received the blessing in 1913 at the age of thirty-seven, three years after he was ordained to the Council of the Twelve Apostles, the second-highest governing body in the LDS Church next to the First Presidency. The patriarch promised him that he would “always be in possession of the spirit of revelation” and that his “counsels will be considered conservative and wise.”[7] The blessing proved prophetic, for Smith’s vigorous defense of the priesthood and temple ban during his sixty-two years as a Church officer marked both his commitment to conservative Mormon teachings and his willingness to defend the ban as revelatory and divine.

Although Smith first discussed the ban in a 1924 article published in the Church’s magazine, the Improvement Era, his most spirited defense of it occurred in 1931 when he published The Way to Perfection.[8] It was one of his most successful publishing ventures, second only to his Essentials in Church History (1922) and perhaps the Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (1938).[9] The Way to Perfection went through eighteen reprint editions and sold tens of thousands of copies, amassing royalties even after his death in 1972. Published in English, German, Dutch, French, Portuguese, Danish, Finish, and Japanese, it did not go out of print until Church authorities removed the hard copy from publication in 1990 and the Amazon Kindle edition in 2018.[10] The book served as the manual for a Sunday School course in genealogy, reflective of Smith’s close association with the Genealogical Society of Utah. The First Presidency approved it, and the book quickly became an authoritative statement on LDS racial teachings.[11]

Smith published The Way to Perfection at a time when Mormon racial teachings were unsettled and when Americans in general struggled to define race.[12] Although Smith and early Church leaders had taught for years that Black people bore the mark of a divine curse—that they merited a black skin for their sinful conduct in a premortal life—these teachings raised more questions than answers. Since the Church’s founding in 1830, leaders offered a variety of conflicting statements about Black people, undoubtedly influenced by the culture of slavery in which they lived. As recent scholarship attests, early LDS leaders could not determine to what degree Black people should be able to participate in the Church’s rituals.[13] Mormon founder Joseph Smith produced three books of scripture that, along with the Bible, later became canonized as the standard works, yet these scriptures were largely silent on the spiritual destiny of African descendants. Correspondingly, the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants—two essential books of Mormon scripture (the other the Pearl of Great Price)—had much to say about Lamanites or American Indians, privileging them for “redemption and whiteness.”[14] By contrast, the Bible—specifically Genesis chapter 4—discussed a “mark” God had placed on Cain, which LDS apostles equated with dark skin, designating Black people unfit to hold the priesthood. The other proof text was Abraham chapter 3 from the Pearl of Great Price, which the Church hierarchy interpreted to mean that Black members were disqualified from the Church’s sacred rituals because they had committed some alleged misdeed or sin before they were born.[15]

Church leaders arrived at these conclusions gradually over the course of the nineteenth century. There is no evidence that Joseph Smith restricted Black people from the priesthood or disqualified them from the Church’s temple rituals. In fact, early records indicate that at least a handful of Black men had been ordained to the LDS priesthood during Smith’s tenure as founding prophet.[16] Some even received their patriarchal blessings, which pronounced their lineage and provided a roadmap to their eternal salvation, and some participated in important temple rituals, served church missions, and presided over church congregations. Black Latter-day Saint women enjoyed special privileges too. They received patriarchal blessings and participated in some temple rituals.[17]

However, the status of Black Latter-day Saints changed dramatically after Joseph Smith’s death in 1844. In the ensuing years, Smith’s successors developed a theology of race that marginalized Black people. In 1845, apostle Orson Hyde was the first Mormon leader to link black skin with moral impurity, declaring that Black people had been neutral in a premortal “war in heaven,” which prompted God to place them “in the accursed lineage of Canaan; and hence the negro or African race.” In 1847, apostle Parley P. Pratt advanced the argument further, insisting that their cursed lineage had disqualified them from the priesthood.[18] In 1852, after Latter-day Saints migrated west to the Great Basin, territorial governor and Mormon prophet Brigham Young reversed Black priesthood ordination and instituted a ban barring Black people from full access to temple rituals. Young announced a “one-drop” rule to determine African heritage, but he provided no guidelines on how to do it.[19]

This rudderless policy left Young’s successors in a lurch, for he never specified how Church leaders could detect one drop of African blood. At the time, there were no ways to detect bloodlines or reliable ways to discern lineage. Light-skinned and biracial people with African ancestry were the most difficult to identify. Their mixed-race status presented additional challenges for LDS Church leaders as they grappled with the uncertainty of not knowing who had Black ancestry.[20]

The “one-drop” rule, moreover, posed another significant challenge for leaders: It negated years of African, European, and Native American cohabitation in colonial North America. These multiracial peoples had shared the continent for hundreds of years, mixing and marrying, which complicated racial policing and made it all but certain that no one truly had a “pure race.” From the convergence of these free and unfree peoples on the North American continent arose new racial identities resulting in “mulattoes,” “mestizos,” “mustees,” and other “mixed bloods.”[21] Determining a cursed lineage was therefore difficult to discern because mixed-race peoples were ubiquitous in early America.

***

Given the inadequate tools to police racial boundaries, LDS Church leaders like Joseph Fielding Smith struggled to define precisely where Black and light-skinned Latter-day Saints fit into the Church’s conception of soteriology. In 1907, as the Assistant Church Historian, Smith called the rationales of the ban “tradition” and “the opinion” of earlier leaders.[22] Here he echoed the view of Church president Lorenzo Snow, who noted in 1900 that he did not know whether the curse of Cain teaching originated with Joseph Smith or Brigham Young. He could not determine if this teaching was the product of revelation or whether Young “was giving his own personal views of what had been told to him by the Prophet Joseph.” Likewise, in 1912, Church president Joseph F. Smith and his counselors Anthon H. Lund and Charles W. Penrose confessed that they did not know of any “revelation, ancient or modern” supporting the teaching that “negroes” were “neutral in heaven,” which was clearly at odds with apostle Orson Hyde’s teachings some sixty years earlier.[23]

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, Church leaders continued to express unease over how the Church had justified its teachings about race. In 1918, apostle Orson F. Whitney wrote that “Ham’s sin, which brought the curse upon Canaan . . . may not be fully known; but even if it were,” he cautioned, “there would still remain the unsolved problem of the punishment of a whole race for an offense committed by one of its ancestors.” In contrast, while Whitney found the Church’s teachings about the premortal existence “unsolved,” apostle Melvin J. Ballard sermonized in 1922 that “it is alleged that the Prophet Joseph said—and I have no reason to dispute it—that it is because of some act committed by them before they came into this life.”[24]

In any event, Joseph Fielding Smith’s labeling Mormon racial teachings “the opinion” of earlier leaders was hardly reassuring to Latter-day Saints who wanted definitive answers about why Black members were barred from the priesthood and temple. When he published The Way to Perfection in 1931, he knew that Mormon racial teachings were in flux, functioning more as speculative theology than as revealed doctrine. At the same time, Smith also knew that the Church lacked a clear-cut revelation affirming the ban, which prompted apostle Ballard to assert that “it is alleged” that it began with Joseph Smith. Joseph Fielding Smith’s father, acting in his capacity as Church president, was even more frank in admitting that “there is no written revelation” to “show why the negroes are ineligible to hold the priesthood.” Nevertheless, he opined that it began with “the Prophet Joseph Smith.”[25]

The uncertainty about the ban’s origins troubled Joseph Fielding Smith throughout his ministry, particularly questions dealing with the fate of Cain and Abel’s posterity. In a letter to a concerned Latter-day Saint, Smith noted that “Abel was cut-off without posterity but according to the doctrine of the Church, he will have posterity in eternity because he is worthy of all the blessings.” Smith further claimed that “until he does, the seed of Cain are barred from holding the priesthood.” When the interrogator expressed skepticism about Smith’s answer, the apostle exasperatingly noted that this issue “comes back to me constantly as a plague.”[26] In another revealing letter, a concerned Church member asked Smith to explain “why the negro has a black skin and why he cannot hold the priesthood. I have heard many different reasons but I would like to know where I can find the true one.” Smith could not answer the question satisfactorily and admitted in the reply letter that the “information we have regarding the Negro is limited.”[27]

Particularly challenging were questions Smith entertained when he visited LDS Church missions. When a missionary in Brazil asked him point-blank, “Where is the revelation denying the Priesthood to the seed of Cain?” Smith stumbled.[28] He couldn’t answer the missionary because neither he nor his colleagues had ever found one. These questions presented a challenge for other Church leaders, too. In 1921, then-apostle David O. McKay embarked on a mission tour to the South Pacific and encountered a “worthy man” with a cursed lineage. McKay promptly wrote Church president Heber J. Grant asking if he could ordain the man to the priesthood, but the Church president said no. “David, I am as sympathetic as you are, but until the Lord gives us a revelation regarding the matter, we shall have to maintain the policy of the church.”[29] Other apostles experienced similar challenges, as did lower-level Mormon leaders. In the early 1970s, Lester Bush, a Latter-day Saint medical doctor, compiled an exhaustive documentary record on Mormon racial teachings, which included dozens of letters from local LDS leaders in which they asked the First Presidency difficult doctrinal questions about Black members, lineage, and the priesthood and temple restriction. Many of them date to the 1910s and 1920s as the Church expanded in the United States and abroad.[30]

This uncertainty and ambiguity prompted Smith to write The Way to Perfection. He sought to quell doubts about the origins of the ban but, more importantly, he wanted to create a theological framework for Black priesthood denial. Among Smith’s most controversial chapters include 15 (“The Seed of Cain”) and 16 (“The Seed of Cain After the Flood”). There the apostle outlined a hierarchy of race based on his interpretation of Mormon scripture, his study of the racial theories of early LDS Church leaders, and his embrace of two secular theories—British Israelism and eugenics—prominent during his lifetime.[31]

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, Mormon leaders were immersed in British Israelism ideology—a Protestant teaching that privileged Anglo-Saxons as God’s “favored lineage.” For Latter-day Saints, these “lost tribes of Israel” had “believing blood,” meaning they were more likely to convert to the LDS Church than groups or races outside of the house of Israel. Mormon Sunday School manuals and other Church publications echoed these views. Such theories reflected similar concepts expressed by Joseph Smith and Brigham Young half a century earlier.[32] Church publications, moreover, informed Latter-day Saints of their chosen status. Unlike persons of African lineage, who were deemed cursed and therefore excluded from the Abrahamic covenant, white people derived their ancestry from Anglo-Saxons and were considered the “covenant race.” To that end, many Latter-day Saints believed that because of their chosen lineage, they had to preserve and protect their “racial purity” lest miscegenation taint their bloodlines.[33]

Smith and his fellow apostles imbibed these ideas, but they also looked to eugenics to privilege hierarchies of race. In the early twentieth century, Latter-day Saints, like many Americans, embraced eugenics—the faddish (and erroneous) idea that science could improve the human race by breeding, good hygiene, and good morals.[34] “A very great deal is expected of this movement,” General Authority B. H. Roberts stated in 1916.[35] Mormon leaders opined that Latter-day Saints were uniquely qualified to improve the human race. As polygamists and virtuous Christians, Mormons would preserve their status as God’s covenant people through child-rearing and righteous living. This required them to shun birth control and embrace proper parenting and child-rearing practices consistent with Latter-day Saint teachings about families. If Latter-day Saints failed in this sacred obligation, Joseph Fielding Smith reasoned, the “more worthy race” would be overwhelmed by “lower classes” of European immigrants then flocking into the United States following the American Civil War. The failure of the “covenant race” to reproduce would lead to “race suicide” putting “themselves and their kind out of this mortal existence.”[36]

All of these ideas culminated in The Way to Perfection, which affirmed Smith’s belief that God privileged racial hierarchies. He insisted that because God had placed a curse upon “negroes,” they were a “less favored lineage,” which barred them from the “holy priesthood.” Furthermore, he argued that because of their “less valiance” in a premortal life, the blessings of the house of Israel did not apply to them like it did the descendants of Ephraim and other “favored lineages.” Only “choice spirits” from a “better grade of nations” could enjoy the full privileges of the Church’s liturgical rites. But Smith did not stop there: He claimed that Black people were an “inferior race,” forever doomed as eternal servants to God’s covenant people. Less dramatic but no less significant, Smith posited that the priesthood restriction began with Joseph Smith, despite the absence of a definitive revelation and despite the fact that Black men had been ordained to the priesthood during his great uncle’s tenure as founding prophet.[37]

The Way to Perfection proved a seminal work. It was the first time that an LDS leader had ever systemized Mormon racial teachings. Several of Smith’s colleagues, impressed by his thoroughness and clear, conversational writing style, recommended chapters 15 and 16 of The Way to Perfection when Latter-day Saints asked about the priesthood ban; Smith himself recommended the same chapters when he fielded similar queries. In addition, the book was cited in LDS Church manuals, in the publications of Mormon prophets and apostles, and in sermons at the faith’s semiannual general conference in Salt Lake City.[38] Most notably, the essential teachings of The Way to Perfection were incorporated into an adult Sunday School manual in 1935. Accompanying the manual was a fifty-three-page “Topical Outline,” which included a section called “Study Thoughts.” These study questions asked students to ponder a number of passages about Black people—in specific, “How do we know the negro is descended from Cain through Ham?” “Name any great leaders this race has produced.” And most dramatic, “Discuss the truth of the statement in the text, p. 101, that Cain ‘became the father of an inferior race.’”[39]

Perhaps most importantly, however, The Way to Perfection became the basis for a First Presidency statement in 1949, in which the Church hierarchy enshrined into doctrine the divine curse and the premortal existence hypothesis. The First Presidency cleared up any ambiguity about the provenance of the ban when they declared unequivocally that it was a “direct commandment from the Lord on which is founded the doctrine of the Church from the days of its organization.”[40] The First Presidency’s bold statement, however, ignored the fact that Black Mormon men were ordained to the priesthood during Joseph Smith’s tenure as founding prophet and that at least one of them participated in limited temple rituals and presided over a Mormon congregation.

Smith followed up The Way to Perfection with additional books that defined and reaffirmed Mormon racial teachings as essential Church doctrine. Along with The Way to Perfection, Smith’s Doctrines of Salvation (1954–1956) and Answers to Gospel Questions (1957–1966) established him as the Church’s foremost authority on the priesthood and temple ban.[41] Because of these definitive works, his fellow Church leaders turned to him to settle difficult questions involving race and lineage. In 1951, for example, Stephen L. Richards and J. Reuben Clark, Smith’s colleagues in the Church hierarchy, wanted to know if Smith could determine if “the inhabitants of the Melanesian and Micronesian Islands” were of “the seed of Cain.” After thoroughly researching the matter in the Encyclopedia of Britannica, Smith claimed he did not know.[42] Similarly, Brigham Young University president Ernest Wilkinson looked to Smith for guidance on whether a prospective student with “one-eighth negroid” ancestry could enroll at the Church-owned school. “What is your advice to me?” Wilkinson asked. “Should we try to discourage him from coming to Provo?” Just as importantly, when LDS Church patriarchs had questions about how to pronounce lineage for Black and biracial Latter-day Saints, they looked to Smith for guidance. He informed them that they had to declare the lineage of Cain.[43]

As Smith’s hardline views on race circulated throughout the Church, some teachers within the LDS Church Educational System challenged him. Lowell Bennion, a highly-regarded Mormon religion instructor at the University of Utah Institute of Religion, criticized him, as did others within the Church Educational System. During one memorable moment in 1954, Bennion “openly questioned” Smith’s racial teachings at a training session attended by dozens of Church seminary and institute teachers at Brigham Young University. Smith took offense at such criticisms, deciding that Bennion was not sufficiently orthodox and had to go. In 1962, Bennion and his colleague T. Edgar Lyon, another critic of the ban, were ousted in a well-publicized purge at the University of Utah Institute of Religion.[44] Smith, who had clashed with Church religion teachers and Mormon intellectuals repeatedly over the years, recorded the experience in his diary: “I received a number of letters of protest because of the release of Drs. Bennion and Lyon who have been at the Institute for a number of years. I have also interviewed some students who were taught by them and reached the conclusion that the change and release was in order.”[45]

Other Mormon intellectuals likewise incurred Smith’s wrath. Sterling McMurrin, a liberal Mormon philosopher at the University of Utah, emerged as Smith’s most vocal critic. The two had clashed since the 1950s, culminating in Church president David O. McKay’s vow to protect McMurrin from Smith, who wanted to excommunicate the outspoken philosopher.[46] Smith’s ire toward McMurrin reached an inflection point when, in 1968, McMurrin delivered a forceful speech to the Salt Lake City chapter of the NAACP in which he condemned LDS racial teachings as “crude,” “superstitious,” and “harmful to the church.” He chided LDS leaders like Smith for maintaining a racist policy and predicted that if the Church did not lift the ban, members would leave. The speech received extended media coverage throughout the United States, causing embarrassment for the Church, already under fire for the priesthood and temple ban.[47] After reading McMurrin’s address, an agitated Smith vowed to excommunicate him again.[48] He failed because of McMurrin’s strong support from within the Mormon intellectual community. Not only was he a one-time United States Commissioner of Education in the John F. Kennedy administration, the grandson of high-ranking LDS Church leader Joseph W. McMurrin, and author of two critically acclaimed books on Mormon theology, but he was close friends with then–Church president David O. McKay and his counselor Hugh B. Brown.[49]

More critically, Smith’s passionate defense of the priesthood and temple ban affected his relationship with counselor Brown, who denounced the “curse of Cain” ideology as “a bunch of gobbley gook.”[50] The two had clashed for years over the ban. Not only did Smith keep Brown out of the Quorum of the Twelve when Church president Heber J. Grant first proposed his name for ordination in 1931, but he vigorously protested Brown’s repeated attempts to lift the ban. The first attempt occurred in 1961 just after McKay appointed Brown as a counselor in the First Presidency. Brown, deeply affected by letters coming into Church headquarters questioning the ban, supported granting Nigerians the Aaronic Priesthood when Church leaders proposed a mission there in the early 1960s. Smith and other hardliners scuttled the move, fearing that ordaining Black men to the lesser priesthood would prompt them to want the Melchizedek Priesthood, the so-called “higher priesthood.”[51]

Establishing the Church in Black Africa prompted heated discussions within the Quorum of the Twelve about ordaining Black men to the priesthood.[52] In 1962, Brown confided to a concerned Church member that the priesthood ban “is having [more] constant and serious attention by the First Presidency and the Twelve than at any time, I think, in the history of Church.”[53] Also that year, Brown informed Lowell Bennion that the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve had been discussing the issue intently. “Almost to a man,” Brown explained, the apostles agreed that “a change would have to take place. President McKay said a change must come, but he didn’t know when.” McKay further reiterated that the “Negro question was the greatest issue the church had faced since plural marriage.”[54]

The following year, Brown escalated the tension between himself and Smith when he violated an unspoken quorum rule by reaching out to the media to disclose sensitive deliberations the apostles had been having about lifting the priesthood ban. “We are in the midst of a survey [now] looking toward the possibility of admitting Negroes,” Brown explained to New York Times reporter Wallace Turner. The counselor’s frank admission prompted Turner to write that “The top leadership of the Mormon church is seriously considering the abandonment of its historic policy of discrimination against Negroes.”[55] Senior apostles, stunned by Brown’s private conversations with Turner, confronted him, demanding an explanation. Embarrassed, Brown said he had been “misquoted,” but a Church public relations employee who heard the interview confirmed the accuracy of Brown’s statement, as did Wallace Turner, who noted that the “quotes that appeared in the story were precisely the words spoken by Mr. Brown.”[56]

Blindsided by the New York Times story, Smith countered Brown. In a public interview, published in October 1963, just a few months after Brown’s interview with the Times, the senior apostle bluntly declared that “The Negro cannot achieve the Priesthood in the Mormon Church.” This was consistent with Smith’s position of the previous year when he claimed that “No consideration is being given now to changing the doctrine of the Church to permit him to attain that status.”[57]

***

Meanwhile, as Smith tussled with First Presidency member Brown over the priesthood and temple ban, Smith also encountered pushback from some of his fellow apostles in the Quorum of the Twelve. The post–World War II years exposing racial injustices with the brutal murder of Emmett Till, the arrest of activist Rosa Parks, and the nonviolent marches of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his supporters brought civil rights issues in the United States under a laser-like focus.[58] Smith’s racial teachings, which were promoted unabashedly within the Mormon community in the 1930s and 1940s, were now spoken of in hushed whispers in the 1950s and 1960s as more Americans, including Latter-day Saints, became attuned to the injustices of Jim Crow America. In the mid-1960s, for instance, the First Presidency dropped chapters 15 and 16 from The Way to Perfection when they published the Portuguese edition of the controversial book.[59] At the same time, they denied permission for BYU religion professor James R. Clark to publish the 1949 First Presidency statement on race and priesthood in a multivolume edition of The Messages of the First Presidency, and they refused to print a controversial address dealing with race and lineage by Church patriarch Eldred G. Smith “because of the present turmoil over the Negro question.” And finally, they instructed Church leaders to refrain from speaking about Black people as cursed or less valiant in public expressions to the media. Our teachings about “negroes,” the First Presidency declared in 1968, must be “clear, positive, and brief.”[60]

Smith was certainly not immune to the changes swirling around him, the Church, or the broader American society. During the turbulent civil rights years, he began to rethink the status of Black people and their place within the Church. When dozens of Latter-day Saints petitioned him asking if the scriptures justified denying Black people civil rights, Smith experienced a change of heart.[61] Sensitive to public criticism about The Way to Perfection, the aging apostle denied in the LDS Church News and in Answers to Gospel Questions that he ever taught that Black people were an “inferior race.” More instructively, he began to champion a qualified version of racial equality for persons of African lineage—this despite Mark E. Petersen, Ezra Taft Benson, and other apostles opposing civil rights at the time.[62] In Answers to Gospel Questions, Smith stated unequivocally that Black people should have equal access “to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,’” adding that they “should be equal in the matter of education” and that they “should be free to choose any kind of employment, to go into business in any field they may choose and to make their lives happy as it is possible without interference from white men, labor unions or from any other source.”[63] Furthermore, Smith did not object to Hugh B. Brown’s landmark 1963 statement in the LDS Church general conference when he proclaimed that “there is in this Church no doctrine, belief, or practice that is intended to deny the enjoyment of full civil rights by any person regardless of race, color, or creed.”[64]

Even so, racial equality had limits for Smith, as it did for many of his colleagues in Church leadership. He shared the fears of miscegenation common in the rest of the nation and he still referred to Black people as the “seed of Cain” in his sermons and writings and even called them “Darkies” during a well-publicized interview.[65] Just as troubling, he did not support specific civil rights bills, although he accepted civil rights as a general concept. When Catholics along with two of the South’s oldest and most prominent regional churches—the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) and the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC)—supported integration and called for protections in jobs and housing, Smith remained conspicuously silent.[66] All the while, he was mindful of how housing and employment bills to prevent racial discrimination could complicate the Church’s anti-miscegenation teachings. He feared that if Black and white people lived and worked among each other, it could potentially lead to dating and ultimately marriage. To an inquisitive Church member, the apostle said forcefully that “It would be a serious error for a white person to marry a Negro, for the Lord forbade it.”[67]

But Smith’s issues with Black people extended well beyond theology; Black music vexed him. He cautioned BYU president Ernest Wilkinson not to permit the “negro twist” at school-sanctioned dances, fearing that this popular dance, which involved a series of gyrations and stomps, would sully the morals of the predominantly white student body. He also demanded loyalty from BYU faculty on LDS racial teachings. He supported a survey, for example, asking two unorthodox religion professors a series of questions about fundamental LDS teachings. One question asked: “Is the Church wrong for not giving the priesthood to the Negro?”[68] Furthermore, Smith expressed ambivalence about proselytizing among persons of African descent. Determining who had “negro blood” was a challenging and serious problem, especially as the Church accelerated its missionary efforts following the Second World War. Proselytizing in racially-mixed countries like Brazil and South Africa posed considerable challenges for Smith and his fellow apostles because missionaries could not determine who had “a cursed lineage.” To avoid controversy, Smith instructed missionaries that “whenever possible” they should avoid teaching persons of African ancestry “in view of the problems which generally arise.”[69]

Smith fumbled on questions regarding Black priesthood ordination as well. When a well-intentioned Latter-day Saint asked him about Elijah Abel, an early Black Latter-day Saint priesthood holder, Smith noted that the “story that Joseph Smith [had] ordained a Negro and sent him on a mission is not true.” On another occasion, he informed a concerned Church member that there were actually two Elijah Abels in Nauvoo in the 1840s—one Black and one white. The white Elijah Abel held the priesthood, he stubbornly insisted. Assistant Church Historian Andrew Jenson stoked the controversy when he published a four-volume book entitled Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, in which he acknowledged that early Church leaders had conferred priesthood ordination on Abel. Smith claimed, without evidence, that Jenson was mistaken, and the apostle huffed that admitting Abel’s ordination had done “the Church a disservice that has turned out to plague us.”[70] To BYU and Church Educational System educators, however, Smith acknowledged Abel’s ordination, even conceding that “perhaps more than one negro” was ordained during the early days of the Church. But he quickly added that “when it came to the attention of the Prophet Joseph Smith, he said it was wrong.”[71]

Why did Smith offer conflicting accounts of Abel’s ordination? Simply put, he could not reconcile Black priesthood ordination with the narrative he created in The Way to Perfection.

Nevertheless, Smith insisted that Black people had a place in the Church. In The Way to Perfection, he commented that “these unfortunate people” could be baptized into the Church but that was the extent of their involvement. In Doctrines of Salvation and Answers to Gospel Questions, he offered more details, outlining the basic functions of the Church in which Black members could participate. They could be baptized, have their children blessed, participate in the sacrament, receive their patriarchal blessings, and even qualify for the “celestial kingdom” if they “remained faithful and true to the teachings of the church.”[72] In that context, Smith declared that “the Church does and can do more for the Negro pertaining to his salvation than any other Church in existence.”[73]

In 1955, at about the same time that Church leaders began to de-emphasize The Way to Perfection, Smith showed another side of himself when, as president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, he proposed a program to the First Presidency to better meet the needs of Black Latter-day Saints in the Salt Lake Valley. He recommended that “all the Negro members in the [Salt Lake] area be organized into a unit and made a part of one of the stakes of Zion.” He envisioned that it would act as “an independent unit which would function somewhat the same as the Deaf Branch or the Spanish-American Branch.” Of the “144 Negroes in this area,” Smith explained, “very few of them are active, undoubtedly because the church has not met their needs.”[74] The following year, he instructed apostle Mark E. Petersen to hold “Cottage Meetings in Negro homes for the purpose of finding out why so few Negroes belonged to the Mormon Church.” On instructions from Smith, his file leader, Petersen promised Black Latter-day Saints that the Church “would build them a chapel of their own where they could worship themselves” if they remained loyal to the Church.[75]

Smith’s proposal did not come to fruition at the time. The First Presidency rejected the proposal because they feared that a segregated unit within the Church would bring unwanted national publicity, especially during the turbulent civil rights years when civil rights activists condemned Protestant churches for segregating their pews.[76] The public, in other words, would assume that the Church wanted to segregate Black and white church attendees when this was not Smith’s intent. He wanted to reactivate Black Latter-day Saints, create a community for them, and provide a hospitable place for them to worship. Years later, his efforts culminated in the founding of the Genesis Group, the LDS Church’s first Black support group.[77]

During the later years of his ministry, Smith also dampened expectations for Latter-day Saints who expressed anguish over Mormon racial teachings. When he was president of the Quorum of the Twelve, he met with a concerned Church member who agonized over the notion that Black people were “less valiant” in a premortal life. As the two searched the scriptures together during one intensely revealing meeting, Smith assured the troubled Latter-day Saint that he did not have to believe in the Church’s racial teachings to stay in its good graces. As the man recounted years later: “President Smith patiently went through the sources with me, particularly the Pearl of Great Price, and then he said something quite remarkable: ‘No, you do not have to believe that Negroes are denied the priesthood because of the pre-existence.’” Smith told his interrogator that he had not received a “revelation on the matter.” The Church member, a liberal BYU professor named Eugene England, was overjoyed at Smith’s frankness and his willingness to make himself vulnerable on a subject that seemed so firm and so entrenched in his sermons and writings.[78]

***

In addition to advocating for civil rights and stand-alone worship services for Black people, Smith began to internalize the consequences of the priesthood and temple ban when Latter-day Saints discovered they had a cursed lineage. He was aware, for example, of the pain that such disclosures caused Latter-day Saint families, for he had interviewed dozens of Latter-day Saints of African lineage. He knew of examples in the Church when branch presidents and bishops discovered their African ancestry, only to be released from their church callings amid embarrassing and painful humiliation. He also knew of instances in heavily-populated Mormon communities when white members refused to patronize businesses after learning that the store owners, many of whom were faithful Latter-day Saints, had “negro blood.”[79]

After hearing about these troubling episodes, and indeed lamenting over them, Smith became more sensitive to Mormon racial teachings toward the end of his life. In the early 1960s, for instance, when Smith was the presiding authority at a Church priesthood meeting, a teacher in the LDS Church Educational System informed him about a young man with a cursed lineage. The young man had been active in the Church, served a church mission, and was scheduled to be married in an LDS temple. His family was also active. His brothers had served in several positions within the priesthood: an older brother served as a stake president, another as a high councilor, and the other in a bishopric. And now the problem: despite having “blond hair and blue eyes,” the young man discovered that he was “128th negro.” His “great-grandfather had apparently gone to the West Indies and married a native woman who was half Negro and half Indian.”[80]

As Smith listened to the story, he was at first impervious to the young man’s plight. Without hesitation, he told the religion teacher that he should instruct the young man to tell his fiancée about his cursed lineage, which meant, of course, that there would be no temple wedding. “Our doctrine is very clear on that,” Smith intoned. But as he pondered the situation further, Smith had a change of heart. At the close of the meeting, he whispered to the religion teacher to see him in private. There, the aging Mormon leader—the man who once said that Black people were inferior—did something dramatic and uncharacteristic for this dogmatic and seemingly unyielding man: He told the religion teacher to tell the boy to keep the matter to himself. Smith explained that if the boy disclosed his ancestry, it would harm himself and his brothers. “All of these [men] have been married in the temple and have participated in Church ordinances,” Smith noted. This disclosure “would ruin their lives.” Smith further instructed the religion teacher to inform the boy not to explain his circumstance to either his fiancée or his bishop. “This is something between him and the Lord, and if the Lord ratifies the sealing in the Temple, who are we to question it?”[81]

Such episodes revealed the increasing difficulty that LDS Church leaders encountered in policing racial boundaries. Indeed, the “one-drop” rule meant that the man noted above could pass as white even though his Church leaders had deemed him Black after learning of his African ancestry. LDS apostles, keenly aware of this reality, lamented that it was “impossible” to determine “those who have Negro blood and those who have not.”[82] During Smith’s lifetime, there were no scientific means to test bloodlines or reliable ways to trace lineage. Thus, Smith and his colleagues knew that they were baptizing and conferring priesthood ordination on persons of African descent, yet they felt powerless to stop it because racial identification had eluded them, much as it did Americans in general throughout the twentieth century.[83] When asked about the “practical problems” of dealing with members who have “one-eighth Negro blood or something of that kind,” Smith’s colleague N. Eldon Tanner candidly stated, “We just deal with them as they come.”[84]

It is impossible to determine how many Latter-day Saints of African lineage flouted the Church’s racial marker and crossed the color line. Scholars are only now beginning to uncover the extent to which these individuals passed as white.[85] Nevertheless, as questions of race and lineage vexed the Church hierarchy, Smith’s belief that the Church should do more to help Mormons of African descent was reinforced. During his brief tenure as Church president, Smith authorized his counselors, Harold B. Lee and N. Eldon Tanner, to form the Genesis Group, the Church’s first Black support group.[86] Formed in 1971, a year after Smith became the Church president, the First Presidency instructed the Genesis Group to hold monthly sacrament services for families, weekly Relief Society meetings for women, and weekly Primary meetings for children. Following Smith’s instructions to the First Presidency in 1955, Genesis members were tasked with reactivating some 250 Black members in the Salt Lake Valley who had drifted away from church activity. At the same time, the elderly Mormon leader wanted to create a spiritual home for Black Latter-day Saints where they could “identify with each other,” as Genesis member James Sinquefield remembered.[87] Today, the Genesis Group spans congregations in nearly a dozen cities in the United States, comprised of hundreds of Black Latter-day Saints who serve in a variety of leadership positions within the Church.[88] Smith’s official biography is silent on this aspect of his Church ministry, yet it marks an important episode in his maturing views toward persons of African lineage.[89]

***

Joseph Fielding Smith, Mormonism’s most important theologian of race in the twentieth century, died in 1972 after having taught for nearly six decades that Black people were cursed. But as his support for the blond-haired, blue-eyed boy suggests and as he became more attuned to the racial injustices faced by Black people, another side of him emerged that was nearly lost on the Church body. His views about Black people had evolved. He was no longer the hard-crusted, doctrinaire theologian as he appeared in The Way to Perfection. Times had changed—and Smith had too. True enough, he still defended the priesthood and temple ban as divine, but he also recognized that persons of African lineage had suffered because of it.

In 1978, Smith’s teachings on race and lineage became moot when LDS Church president Spencer W. Kimball lifted the 126-year-old priesthood and temple ban, some six years after Smith’s death.[90] Kimball’s revelation announcing the end of the ban led to new racial doctrine, for it prompted Mormon apostles to challenge Smith’s most fundamental claims in The Way to Perfection. None other than Smith’s son-in-law, apostle Bruce R. McConkie, himself a controversial figure within the Mormon community, played a critical role in this endeavor—this despite his own anti-Black teachings in his seminal book Mormon Doctrine.[91]

In an important memo to President Kimball, just weeks before the priesthood revelation, McConkie collapsed the theological scaffolding for Black priesthood denial when he insisted that Black people could be “adopted” into the house of Israel by virtue of their priesthood ordination. He averred that “Negro blood” would be purged from their bodies when they converted to Mormonism, thereby making them heirs of the Abrahamic covenant.[92] Following the priesthood revelation, McConkie continued to finesse his late father-in-law’s teachings. He proclaimed that God favored all groups and lineages equally, doing so in a prominent address called “All Are Alike Unto God.” McConkie likewise asserted that God had lifted “the ancient curse” on Black people, making their past misdeeds in a premortal life both obsolete and irrelevant.[93]

As the twenty-first century approached, Church authorities continued to slice away at Smith’s racial theology. In 1978, less than two months after the priesthood revelation, Spencer W. Kimball asked the apostles not to teach that Black people lacked moral impurity in a premortal life. Neither did he want them to sermonize on the “curse of Cain,” which further distanced the Church from Smith’s embattled teachings. “We just don’t know what the reason was” for the priesthood and temple ban, Kimball concluded.[94]

In 2013, the Mormon hierarchy eclipsed the last vestiges of Smith’s racial teachings when it publicly repudiated them. In an important document entitled “Race and the Priesthood,” posted on the LDS Church website, high Church leaders condemned “the theories . . . that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse” and the notion that the priesthood and temple restriction reflected the “unrighteous actions [of Black people] in a premortal life.” At the same time, the essay acknowledges that Black men held the priesthood during Joseph Smith’s tenure as founding prophet and, just as importantly, that Brigham Young had implemented the ban. And finally, the Church hierarchy denounced the idea that Black people “or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else,” unambiguously repudiating Smith’s most controversial claim.[95] In these stunning admissions, the Church hierarchy demonstrated just how far it was willing to go to confront and condemn Smith’s racial teachings. What is most remarkable, though, is that the “Race and the Priesthood” essay places Latter-day Saints among the ranks of the penitent: Latter-day Saints had now joined Presbyterians, Southern Baptists, and Pentecostals in expressing regret for their anti-Black teachings.[96]

The author wishes to thank W. Paul Reeve, Matthew Bowman, Newell G. Bringhurst, Armand L. Mauss, Becky Roesler, Taylor G. Petrey, and Stirling Adams for their warm encouragement. Each reviewed a draft of the article and provided constructive feedback.

[1] This article uses Latter-day Saint, LDS, and Mormon interchangeably. All denote members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[2] Smith to Henderson, Apr. 10, 1963, Matthew Harris files. We can glean the contents of Henderson’s letter from Smith’s response.

[3] For more on Smith condemning Mormon intellectuals for expressing unorthodox views, see Thomas Simpson, American Universities and the Birth of Modern Mormonism, 1867–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 115–17; Philip L. Barlow, Mormons and the Bible: The Place of Latter-day Saints in American Religion, rev. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 136–41, 156–57, 170; and Richard Sherlock and Jeffrey E. Keller, “The B. H. Roberts, Joseph Fielding Smith, and James E. Talmage Affair,” in The Search for Harmony: Essays on Science and Mormonism, edited by Gene A. Sessions and Craig J. Oberg (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1993), chap. 6. Smith’s most important book advancing his position on science and religion, particularly as it relates to evolution, is Man, His Origin and Destiny (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1954).

[4] Reid L. Neilson and Scott D. Marianno, “True and Faithful: Joseph Fielding Smith as Mormon Historian and Theologian,” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 1 (Winter 2018): 7. See also “New Volume of ‘Answers’” in the Church News, published in the Deseret News, Nov. 26, 1966, in which the editor stated that Joseph Fielding Smith “is known Church-wide as an authority on Church doctrine. It has been said of him: ‘In the Church he is a scriptorian without peer. . . It would be difficult to find a subject of Church doctrine or history that President Smith has not written extensively upon in magazine articles, pamphlets and books.” Matthew Bowman notes that Smith was one of “Mormonism’s most respected religious thinker[s]” in the decades after World War II. In Matthew Bowman, The Mormon People: The Making of An American Faith (New York: Random House, 2012), 200.

[5] For three hagiographic accounts of Smith, see Joseph F. McConkie, True and Faithful: The Life Story of Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971); Joseph Fielding Smith Jr. and John J. Stewart, The Life of Joseph Fielding Smith, Tenth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972); and Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph Fielding Smith: Gospel Scholar, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992).

[6] An LDS Church patriarch is an ordained position within the LDS lay priesthood. Patriarchs give special blessings to the Mormon faithful, providing them with comfort, guidance, and caution. Patriarchs also declare lineage in these blessings. For more on LDS patriarchal blessings, see Irene M. Bates, “Patriarchal Blessings and the Routinization of Charisma,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 26, no. 3 (Fall 1993): 11–29; Matthew L. Harris, “Mormons and Lineage: The Complicated History of Blacks and Patriarchal Blessings, 1830–2018,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 51, no. 3 (Fall 2018): 83–129; and Irene M. Bates and E. Gary Smith, Lost Legacy: The Mormon Office of Presiding Patriarch, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018).

[7] Blessing of Joseph Fielding Smith by Patriarch Joseph D. Smith of Fillmore, Utah, May 11, 1913, box 3, folder 9, Irene Bates Papers, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter JWML).

[8] Joseph Fielding Smith, “The Negro and the Priesthood,” Improvement Era 27 (Apr. 1924): 564–65; Joseph Fielding Smith, The Way to Perfection: Short Discourses on Gospel Themes, 5th ed. (1931; repr., Salt Lake City: Genealogical Society of Utah, 1945).

[9] Joseph Fielding Smith, Essentials in Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1922); Joseph Fielding Smith, ed., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith: Taken from His Sermons and Writings as They Are Found in the Documentary History and Other Publications of the Church and Written or Published in the Days of the Prophet’s Ministry (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938). Mormon rare books dealer Curt Bench estimates that these two books were among the most influential Mormon books ever published. See Curt Bench, “Fifty Important Mormon Books,” Sunstone 14 (Oct. 1990): 55–57; and Neilson and Marianno, “True and Faithful,” 9–10. Gregory A. Prince, Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2016), 185, notes that Essentials of Church History “sold about ten thousand copies a year.”

[10] For the popularity of The Way to Perfection, see Gibbons, Joseph Fielding Smith, 311, 370; and Smith Jr. and Stewart, Life of Joseph Fielding Smith, 210–11. For the publishing history of The Way to Perfection, see Stirling Adams’s video, “Race, Lineage, and the 1920s–1940s Genealogical Society of Utah,” DialogueJournal.com, Mar. 27, 2019.

[11] Topical Outlines to the Way to Perfection (Salt Lake City: Genealogical Society of Utah, 1936), 1.

[12] In the early twentieth century, laws defining racial groups varied from state to state. Some states defined “negroes” as anyone with one-eighth African ancestry, some with one-sixteenth, while others “one drop” or one-quarter. The best studies of the construction of race in the United States include Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2008); Peggy Pascoe, What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009); and Peter Wallenstein, Race, Sex, and the Freedom to Marry: Loving v. Virginia (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2014).