Articles/Essays – Volume 51, No. 3

Roundtable: A Balm in Gilead: Reconciling Black Bodies within a Mormon Imagination

I want to begin by reading a prose poem to give context to my remarks on Black bodies and reconciliation. It is entitled “Blackness” by Jamaica Kincaid.

How soft is the blackness as it falls. It falls in silence and yet it is deafening, for no other sound except the blackness falling can be heard. The blackness falls like soot from a lamp with an untrimmed wick. The blackness is visible and yet it is invisible, for I see that I cannot see it. The blackness fills up a small room, a large field, an island, my own being. The blackness cannot bring me joy but often I am made glad in it. The blackness cannot be separated from me but often I can stand outside it. The blackness is not the air, though I breathe it. The blackness is not the earth, though I walk on it. The blackness is not water or food, though I drink and eat it. The blackness is not my blood, though it flows through my veins. The blackness enters my many-tiered spaces and soon the significant word and event recede and eventually vanish: in this way I am annihilated and my form becomes formless and I am absorbed into a vastness of free-flowing matter. In the blackness, then, I have been erased. I can no longer say my own name. I can no longer point to myself and say “I.” In the blackness my voice is silent. First, then, I have been my individual self, carefully banishing randomness from my existence, then I am swallowed up in the blackness so that I am one with it. The black body is a racialized assemblage of the physical, spiritual, and emotional form. This form inhabits a peculiar existence within the American consciousness. In The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. DuBois referred to freed black people as “refugees.” Author Michelle M. Wright, in Becoming Black: Creating Identity in the African Diaspora, describes African Americans as individuals fixed in the dwelling of the settler colonialist. Both point to a people in suspension. It is in suspension that the black individual crafts an identity, upheld by social, theological, and political discourses predicated on categorization. Likewise, black Latter-day Saints negotiate their subjectivity in the backdrop of a Church body embedded in its racialized history. My remarks are reflections on the suspended as well as the suspension itself.

I acknowledge that “Black,” “Blackness,” and Black bodies differ across time and space. Varied socio-political exchanges between indigenous groups in Africa, citizens of the Afro Atlantic, and white Europeans make it challenging to define a monolithic Black identity. Still, I predicate my remarks on the belief that Mormonism is, arguably, a uniquely American religion. As such, I’ve formed my opinion around reflections on the construction of race in America as a social artifact, an artifact assembled by social, theological, and political theories and practices exchanged between institutions and individuals. In other words, I posit that race is a process of being and becoming. Black Latter-day Saints became Black through the enfleshment of the curse of Cain—whether one identified as Haitian, Ghanian, or Malian, among others—in the Mormon imagination.

Mormonism incorporated prevailing American ideas on race, championing a “pure and delightsome” white subject, the inherently guilty Black Other, and the significance of lineage in determining both, over the course of the latter half of the nineteenth century into the twentieth century. The condemnation of Blackness rang heavily within nineteenth-century America’s flourishing religious landscape. Though some groups and individuals supported abolitionist or integrated visions of community, pro-slavery advocates and segregationists often nodded to the curse of Ham to justify chattel slavery. Meanwhile, pro-slavery preachers used scriptural references to slavery to embolden the enslaved to remain obedient. In Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, author Harriet Jacobs recalls the words of a white reverend. She wrote:

The reverend gentleman knelt in prayer, then seated himself, and requested all present, who could read, to open their books, while he gave out the portions he wished them to repeat or respond to. His text was, ‘Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ.’

Here, the “reverend gentleman” establishes an association between Christ and the slave master.

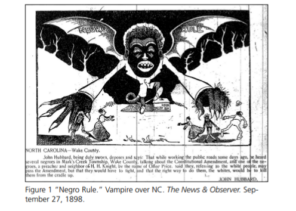

Lineage, as we know, underscored the creation and maintenance race in the Mormon imagination for some time. What we do not speak about in enough detail is the co-constitution of race, theo-ideologies, and lineage. Israelite lineage played a role in the development of what womanist theologian Kelly Brown-Douglas calls the “Anglo-Saxon myth.” The conflation of Israelite narratives and the racialization of bodies, Brown-Douglas notes, gave rise to a theo-ideology that recognized white frames as sacred and protected. The Anglo-Saxon myth sustained the belief that God created the white body in God’s image. The existence of the Black body, then, existed as its opposite: dangerous, unruly, and, at times, demonic.

During a confrontation in 2014, Darren Wilson, a police officer then employed by the Ferguson Police Department, shot Michael Brown, a Black eighteen-year-old from Ferguson, Missouri. When asked about the incident, Wilson stated that at one point, Michael Brown appeared to him as a demon. His words evoked the imagery of the battle between good and evil, in which good ultimately prevails. In this way, Wilson’s rhetoric implicates Michael Brown’s Black body as something to be defeated, thus justifying his death. Whether Darren Wilson saw the face of a demon moments before he ended Michael Brown’s life is not the question. Instead, what are the implications of the connection made between Blackness, evil, and sin?

Nineteenth-century sociopolitical thought situated free Black bodies as the opposite of Western standards of reason, virtue, and purity. Though then prophet-President Joseph Smith campaigned on an anti-slavery platform in 1844, he once warned that abolition would “set loose upon the world a community of people who might peradventure, overrun our country and violate the most sacred principles of human society, chastity, and virtue.”[1] Among his white Christian contemporaries, Smith was not alone in his beliefs about the supposed dangers posed by free Black people. Though the priesthood and temple restrictions did not originate in Smith’s lifetime, American civil and religious discourses on race arguably underlined his and other early LDS Church leaders’ interpretations of relationships between white and Black individuals. Also, it is these explanations, disseminated among the Church body, which bore a theology of racial difference. In the Mormon imagination, the priesthood and temple restrictions converged at the points of racialization, materiality, and theology, inscribing the curse of Cain into flesh. No longer able to fully participate in their faith tradition, Black members of the LDS faith had to redefine their relationships with God, the LDS Church as an institution, other members, and themselves.

In Black Skin, White Masks, sociologist Frantz Fanon describes an experience of alienation through his first encounter with the white gaze. He explains:

‘Look, a Negro!’ It was an external stimulus that flicked over me as I passed by. I made a tight smile.

‘Look, a Negro!’ It was true. It amused me.

‘Look, a Negro!’ The circle was drawing a bit tighter. I made no secret of my amusement.

“Mama, see the Negro! I’m frightened!” Frightened! Frightened! Now they were beginning to be afraid of me. I made up my mind to laugh myself to tears, but laughter had become impossible.[2]

And then the occasion arose when I had to meet the white man’s eyes. An

unfamiliar weight burdened me.[3]

Fanon spoke of the disorientation that occurs when one’s bodily schema is challenged and distorted beyond comprehension. He internalized this gaze—the watchful eye of a child tied to a past that trapped white and Black individuals in perpetuity.

From the time in which early LDS Church leaders implemented the racial restrictions to the present, Black and white Latter-day Saints have been engrossed in the past from which neither can easily escape. Elder Bruce R. McConkie in 1978 admonished members to:

Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or President George Q. Cannon or whomsoever has said in days past that is contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding and without the light and knowledge that now has come into the world.[4]

As much we may hope that one would disregard the explicitly racial teachings of the past, the significance of corporeality in the Mormon imagination is such that Mormonism’s racial wounds run deep. Without a thoughtful consideration of the impact of the priesthood and temple restrictions, their legacy manifests in implicit and explicit ways.

Here, Black Saints negotiate their identity concerning faith, reli gious practice, culture, and history. Am I Black first and Mormon second? Alternatively, am I Mormon first and Black second? The answer may mean the difference between recognition or rejection by the broader community. As one who practices Mormonism, I know that the restrictions are a part of my identity. It is my Black body that was believed to be cursed. However, to internalize that means annihilating a part of myself. Something very curious happens when the images of the divine that reside in holy places don’t look like you. Moreover, though the restrictions dissolved, the revelatory voices continue to come from white Western lips. When you’re told that you should marry someone who shares similar cultural values—knowing the interconnectedness between culture, ethnicity, and race—microaggressions turn into macroaggressions.

“But you’re not like other Black people.”

“Oh, I have a Black friend in the ward.”

“There’s a difference between these two areas we served in—the other area is more ghetto; this area has more educated people.”

When you’re called a nigger in the temple, one may begin to wonder: was I cursed?

To go about the work of healing the Black body within the Mormon imagination, we look toward an alternative vision that acknowledges it in its entirety. I speak not only to the LDS Church as an institution but to the body of Mormonism itself.

Ask yourselves, do representations of Blackness and deep skin tones in Mormonism embody the call that “all are alike unto God”? How would you react to a depiction of God with black or brown skin? Would you find comfort? Representation—not in pursuit of managing a quota or the placation of guilt—is the counter-narrative to the construction of race within the Mormon imagination. We find wholeness in seeing ourselves in the eternal in that we recognize that our existence is not an aberration, but instead, it is intentional. Speaking

to Black Latter-day Saints, this includes seeing yourselves. “(There Is) A Balm in Gilead” references Jeremiah 8:22, and also, an African American spiritual. The first verse of that spiritual reads as follows,

There is a balm in Gilead

To make the wounded whole;

There is a balm in Gilead

To heal the sin-sick soul.

The balm is the hope found in Christ, whose life and ministry provided an alternative vision for those at the margins, a vision of healing, a vision of hope, a vision that makes the wounded whole. It is in this alternative vision that the work of reconciliation begins. Because when you see people as God sees us, in understanding all of us, it is indeed transformative.

[1] Joseph Smith, Letter to Oliver Cowdery, Kirtland, Ohio, ca. Apr. 9, 1836; Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, 2, no. 7 (Apr. 1836): 289–91, The Joseph Smith Papers, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/ letter-to-oliver-cowdery-circa-9-april-1836/1.

[2] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, translated by Charles Lam Markmann, forewords by Ziauddin Sardar and Homi K. Bhabha (London: Pluto Press, 2008 [1986]), 84.

[3] Fanon, Black Skin, 83.

[4] Bruce R. McConkie, “All Are Alike unto God,” BYU Speeches, Aug. 18, 1978, https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/bruce-r-mcconkie_alike-unto-god-2/.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue