Listen on Apple Podcasts.

Listen on Spotify.

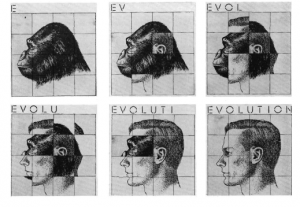

Dialogue is proud to launch a new monthly podcast series on the dialoguejournal.com/topicpages, exploring key issues in the history of LDS scholarship. Join host Taylor Petrey, editor of Dialogue and associate professor of religion at Kalamazoo College as he studies Evolution as viewed through the scholarship found within Dialogue’s pages.

Transcript

Hello and Welcome to the newest episode in Dialogue Topics. I’m Taylor Petrey, editor of Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought. This season we are talking about the history of LDS scholarship on speciific themes, explring a topic indepth and to consider how Dialogue has been a forum for these important issues since its founding. We’ll also bring you up to date on these topics with our more recent issues to discuss some of the current trends. All of our topics pages are curated to bring you comprehensive collections of annotated scholarship and may be found at dialoguejournal.com/topicpages, all one word or navigate there from our homepage. you’ll find amazing resources and research on tons of issues. And thanks for your sustaining support.

This month, we are looking at the history of scholarship on Evolution. Now, this one is a little different from others. It is a topic that once dominated the pages of Dialogue and was a major controversy for most of the 20th century. However, its moment has largely past, at least in scholarly circles the issues is settled. Still, it is useful to track the issue.

That’s because it remains controversial in certain demographics, and acutely so in our community as a whole. According to the PEW report, one of the most reliable surveys on religion in American life, more than half of all Latterday Saints believe that humans always existed in present form. Only 11% believe that humans evolved due to natural processes, and 32% who say that we evolved some other way.

That puts us near the bottom of religious groups that accept natural evolution in America. Compare to Catholics, where only 27% say that humans have always existed in present form and 69% say that humans evolved. Those are flipped among white evangelicals, with 60% denying human evolution and 36% accepting evolution in some form. Only 12% of white evangelicals accept evolution according to natural processes. Evangelical protestants, Mormons, and Jehovah’s Witnesses are the three religous groups least likely to accept evolution. Buddhist, Hindu, and Jewish religous groups in the US are the most likely.

So, in order to tell the story of how we got here, it is useful to talk about where we came from, and how we have evolved over the years…

Act I: Before Dialogue

In 1859, Charles Darwin finally published his book, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. It is impossible to overstate the impact that this book had.

The issue gradually transformed American christianity as it confronted new scientific advencements on evolution, as well as geology. Both of these discpilines challenged simplistic readings of the Biblical timeline and creation story, suggesting the world and the human species was much older than the bible indicated. When this was coupled with new historical and literary approaches to the bible that challenged traditional history, Christianity found itself backpedalling and attempting to adapt to these new discoveries.

So, Latter-day Saints weren’t totally cut off from these discussions. But the first major address came on the 50th anniversary of Darwin’s Origin of Species. In 1909, the First Presidency issued an authoritative document titled “The Origin of Man.” This argued for a historical Adam, created as the offspring of God, and denied that humans evolved. There wasn’t much of a middle ground sought here.

This 1909 statement had some pretty important consequences, because many Latter-day Saints had been receiving education at eastern schools like Chicago, Columbia, and Harvard, and were bringing this back to the Saints. In 1911 at the Brigham Young Academy a controversy erupted when some of the professors were teaching evolution and critical approaches ot the Bible. These were believers who were trying to reconcile these new discoveries with their faith, as modernist protestants were doing, but many church leaders were uncomfortable with their solutions to the problems, preferring to believe the problems themselves were based on false premises.

These conflicts between the modernists who thought science and belief were compatible and the fundamentalists who thought that belief superceded secular knowlege engulfed Christanity in the first half of the 20th century. The famous Scopes Monkey trial in 1925 was a classic example of the conflicts over evolution in public schools, for instance, that hinged on modernist and fundamentalist approaches to biblical hsitory. These controversies included Mormonism. Modernists like BH Roberts, James E. Talmage, Henry Eyring, Sterling McMurrin, and others from this period confronted these issues, including evolution attempting to find solutions. Fundamentalists like J. Reuben Clark, Joseph Fielding Smith, and others decried such efforts and drew on fundamentalist Christian ideas.

The fundamentalists gained the upper hand, for a variety of reasons, though they have never fully controlled the church. For our history, the most powerful however is Joseph Fielding Smith. In 1954, after BH Roberts and James E Talmage passed away, Joseph Fielding Smith published Man, His Origin and Destiny, just 5 years before the 100 year anniversary of Darwin’s text on origins. Smith drew heavily on Seventh Day Adventist creationist George McCready Price. Man: His Origin and Destiny was a hugely popular book attacking evolution and any moderate position that attempted to make it compatable with the Bible. He wrote elsewere, “if evolution is true, the church is false.” Now, the church president at the time, David O. McKay wasn’t particularly happy with this and made clear that there was no official church position on evolution, but when a popular apostle, and his son in law Bruce R. McConkie, repeatedly teach that evolution is a satanic idea, it is hard to persuade the general membership to remain neutral on the matter. The fundamentalist approach framed evolution as an existential threat to the truthfulness of the church’s teachings. Intellectuals in the church were pushing back against this extremism, and had support from other senior church leaders, but they were drowned out.

One last issue that I want to point out, and that is that the church membership actually got increasingly conservative on this issue. In 1935, 36% of BYU students denied the evolution of human beings. That is a pretty small minority. By 1973, 81% of BYU students denied evolution.

So, when Dialogue is born in 1966, this was already an old conversation, more than a century old. There had been members of the church, including very senior ones, who accepted evolution and sought to reconcile it with their religious views, but as we enter the 1960s, those who accepted evolution were increasingly pushed to the side It was bound to be an issue that Dialogue took up.

Act II: Prophetic and Scientific Authority in Conflict

Dialogue isn’t a scientific journal, and one of the challenges of writing about evolution is the specialized scientific knowlege. But this issue transcended the boundaries of traditional science and went right to the heart, for many, of the truth claims made in the bible about the creation of humanity. But it was also embedded, as I mentioned, in a whole host of other scientific challenges to religious belief.

The first time the topic is addressed in Dialogue is the Autumn/Winter 1973 issue that has a whole dedicated collection on “Science and Religion.” It is worth mentioning that Joseph Fielding Smith was president of the church at the time these essays were written, which is important becuase of his strong teachings opposing evolution.

There are a couple of short essays in this issue. Robert Rees, “Science, Religion, and Man.” He wrote expressing the compatablist view: “what we need is a new alliance between science and religion based on mutual trust and a recognition by each of the uniqueness of the others contribution to man’s life. When either science or religion acts as if it has exclusive rights in the domain of truth, it is a guarantee that the truth will not be served.”

There is also Richard Haglund, “Science and Religion: A Symbiosis.” This further expressed the views of compatability. Haglund is the father of Kristine Haglund, the eidtor of Dialogue for much of the 2000s.

There is a great interview in this issue with Henry Eyring, the most accomplished LDS scientist from the first half of the 20th century. He was interviewed by Ed Kimball, son of Spencer W. Kimball. Ed became a really important historian.

Next in this issue is Clyde Parker, “Dialogues on Science and Religion.” These are also interviews with different anonymous LDS scientists asking how they reconcile their beliefs. One of these is a converswtion with a biological scientist that gets into evolution.

However, for our purposes, the most important article in this 1973 issue is “Seers, Savants and Evolution: The Uncomfortable Interface,” by Duane E. Jeffrey. Jeffrey is one of the most important scholars on this topic in the late 20th century. He was a professor of intergretive biology at BYU for many decades and has many important publications. This was a really important essay that was republished a number of times—some consider it one of the most important articles published in Dialogue, comparing it to Lester Bush’s foundational article on race. It was not only the most sophisticated treatment of the topic by any Latter-day Saint up until that time, but in some ways the only sophisticated treatment.

Jeffrey picks right up from Darwin, and indicates that Mormons really haven’t dealt with this issue seriously. He notes that church leaders have opposed it, but also that Latter-day Saints have lots of tools for dealing with this issue. We don’t believe in biblical infallibilty or literalism generally. We don’t believe in ex nihilo creation, and more. So, he looks at the age of the earth in LDS teachings, the fixity of species, the source of life, the special creation of humanity, and so on, and finds a lot more variety in early LDS thought than the fundamentalist persepctives. The Pratts and Brigham Young, for instance, had huge disagreements on related matters. Jeffrey also responds to the 1909 statement, and other authoritative statements from church leaders after that. He specially leaned on those that emphasized that there was no official church teaching on the matter, suggesting those superceded not only 1909, but all subsequent statements that suggested that the church opposed evolution. So, the article is really good for laying out the history of LDS teachings on the matter, including extensive quotes from primary sources, up through the conflicts between David O McKay and Joseph Fielding Smith on the matter. Ultimately, Jeffrey puts forward his view that God works through evolutionary processes: “Mormonism is committed to the concept of a lawful, loving, orderly Deity to whom capriciousness and deceit are anathema. The concept that God works through universal law, that He is God because of His obedience to and operation within the framework of such law, is fundamental. This gives Mormonism a basis for synthesis that exists in few if any other Western religions; it cannot be ignored with impunity.”

The 1973 issue was a sensation. A letter to the editor said: “Thanks for another superb issue of Dialogue. The issue on Science and religion was most timely. One would wish that every teacher from the Mormon ranks would read it and come to mental grips with the problem of what constitutes the basics of our religion and what should be left to scientific study. …Yes, I have a knot in my stomach! I have seen too many minds closed by well-meaning teachers who thought they were saviours of the cause. You see, I am a geology teacher and too often have the opportunity to ob- serve these mind sets in action.”

The following year in 1974, Dialogue published “Sees, Savants and Evolution: A Contiuing Dialogue.” This was a collection of brief responses to Jeffrey’s article, kind of like letters to the editor. It also included a reponse by Jeffrey. Stephen and Kathy Snow begin: “Duane Geoffrey is to be thanked for his article, seers savants and evolution: the uncomfortable interface. It is an excellent summary of the history of thought on evolution of the church to illustrate its power, it made us very carefully reconsider our own anti-evolution bias and again perceive evolution as a possibility.” It then went for a very big, “However,” and argues against evolution and reconciliation. At the same time, the authors were open to those who accepted evolution in good faith as not apostates, so that was something. Dow Woodward chastised Jeffrey for “not going far enough” and coming accross as an “apologist for the church.” Norman Eatough was tough on the other end: “Jeffrey’s willingness to compromise church history to reach a conclusion that the church has not taken a stand against his pet scientific dogma has an all-too-familiar tone. Readers of dialogue were entitled to more than selected rehash of quotes on creation and evolution to reach the dubious conclusion that no stand has been taken.” He gives several examples, including “The views of Joseph Fielding Smith should be enough to convince anyone that a president of the church has articulated a position against evolution.” This response was and remains typical of many who oppose evolution, who want to emphasize all of the times church leaders have condemned it rather than the times church leaders have professed neutrality. It reveals a long-standing weakness of church governance, where extreme conservative positions are professed alongside statements of neutrality from more moderate voices, but the conservative stridency often wins the day. Duane Jeffrey’s long responses demolishes Eatough’s analysis, with more minor attention to the Snows, if you’re interested in a reading a good tussle.

There were bigger tussles going on too. the article made its way to Ezra Taft Benson, an arch conservative apostle. Benson was flabbergasted by the article, according to reports, especially since it was written by someone at BYU. The following here, he denounced evolution and BYU professors who taught it at a BYU fireside. Several people tried to get Jeffery fired over it, but BYU President Dallin Oaks saved him, with the help of Gordon B. Hinckley. Apparently the efforts to get Jeffrey fired continued for many years afterward. As late as 1970, Benson was recommending Joseph Fielding Smith’s book Man: His Origin and Destiny to parents as a rebuttal to evolution as taught in public schools to children.

The problem of a recent church president, Joseph Fielding Smith, speaking out so forcefully against evolution, really did put those who accepted evolution on the defensive. Smith certainly didn’t believe that the church was, or should be, neutral on the matter. But in 1979 there is a great little article shedding light on the authority of Smith’s infamous book, Man: His Origin and Destiny. We saw that many considered this to be the definitive treatment of the subject by church leaders. But, Professor William Lee Stokes, head of the department of geology at the University of Utha, submitted an important piece of evidence into this converstaion with his brief piece, “An Official Position,” published in 1979. This is a brief article, more of a note. But it includes a reproduction of a peronsal letter that Stokes recieved from President David O. McKay on Feb 15, 1957. “Dear Brother Stokes, Your letter of February 11, 1957 has been received. On the subject of organic evolution the Church has officially taken no position. The book, “Man, His Origin and Destiny, was not published by the Chruch, and is not approved by the Church. The book contains expressions of the author’s views for which he alone is responsible. Sincerely your brother, David O. McKay.” He understood that given his position at the UofU teaching many LDS students, and the stated reasons for his inquiry, he should share the letter with anyone who might be confused, but he kept it private without explicit permission. In 1968, he inquired about sharing the letter and was granted permission. The idea that the church had no official position on the topic of evolution has been repeated many times since, but the unofficial position that the church opposes evolution continued to be popular.

Act III: Normalizing Evolution

The issue remained a slow burn controversy. In 1984, Cedric Davern. Davern was a geneticist and professor of biology at the University of Utah, who published his artilce, “Evolution and Creation: Two World Views.” The origins of the article traced back to 1982 and Davern engaged in a debate with a creationist named Dwayne Gish, who was the associate director of the Institute for Creation Research at the time. It is a useful summery of key disagreements on teh meanings of terms and concepts, and again makes teh case that evolution and religious belief are not mutually exclusive. In particular, he traces the idea of providential evolution, a view put forward by many christians who sought to reconcile divine creation with organic evolution. This view held that God was the designer who set in motion or otherwise shaped the processes of evolution.

More than a decade past in the materials that I could find before the subject was addressed again. There was an article, David Bailey, “Science and Mormonism: Past, Present, and Future,” in the Spring 1996 isusue. This is a great article, examining the quesiton of the church’s historical approach to science, and asking whether it will be able to adjust to further developments. In the periodization offered here, Bailey argues that in the 19th century, Mormonism was in fact open to new scientific views and tried to make LDS revelations compatiable with the popularized science of the day. But by 1930 a fundamentalism began to take over. By 1954 Joseph Fielding Smith’s anti-scientific perspectives really took off. While there were several leaders in teh 50s-70s that were open to scientific perspectives, especially evlution, but others remained vocal opponents. By the 1990s, he noted a general softening among LDS leadership and in published materials. The he turns to the future. 25 years later it is interesting to see how his predictions played out. He anticipates discussion of climate change as well as new DNA research emerging, and many others. He mostly asks questions about how how theology and church teachings might adapt. “Fortunately,” he says, “the church has one important advantage over many other religious denominations in dealing with teh challlenges of science: its belief in continuing revelation.”

In Winter 2002 we see a whole set of articles dedicated to science and religion. There are a lot of really great articles here covering evolution, as well as other topics. We are going to focus just on the evolution articles.

First up, is actually an interview with Duane Jeffery, “Thoughts on Mormonism, Evolution, and Brigham Young University.” Jeffery was a professor of Zoology who’d published that groundbreaking article in 1973. In the interview, he talks about how he got into science as a profession, and how he was influenced by the progressive LDS tradition that was thinking about science and religion together. He talks about his experience teaching at BYU, including how BYU Religious Education was the primary source of opposition to evolution at BYU in the 1970s. “One of the members of the religion faculty wrote a seven-page letter to his dean to tell him he would never participate in such a Satanic enterprise as meeting with the scientists on campus, and he never did show up.” There are lots of great anecdotes, but most important is the story of what happened in 1992. It was that hear that the Board of Trustees at BYU approved teh creation of a packet of information that countered the anti-scientific biases on campus. It includes the earlier anti-science statemetns such as the 1909 first presidency letter, but also those which indicate that there is no official doctrine on evolution. It is handed out to all students at BYU whenever evolution is taught. Anyway, there is a lot more about the problems of creationism and more juicy gossipy stories. Its super fun to read.

Next up is Michael Ash, “The Mormon Myth of Evil Evolution.” This was in the same 2002 issue. This reprises some of the history of contoversies over evolution since 1909, and makes the case, somewhat strangely, that this is not an antievolution text and is consistent with the official position that there is no official position. Anyway, it goves into a lot more detail on various turning points and episodes in LDS history in the 20th century, focusing especially on controversies over “pre-Adamites,” a dispute over one of the ways that BH Roberts and Talmage and others proposed to solve the problem of evolution, that Adam was not the first human, but the first human to have a relationship with God. It also gives lots of good documentation about just how controversial Joseph Fielding Smith’s book had been among senior church leaders, who seemed to be telling everyone who asked that it was simply an opinion. However, as we mentioned before, they did little to counter its influence publicly. Ash’s article then offers more details about controversies at BYU, including when Dallin Oaks arrived there as presient in 1971 and had to negotiate conflicting feelings and support the scientists on campus. Ash also gives more info on the current moment at BYU in the 1990s, and the important entry on Evolution in the 1992 Encyclopedia of Mormonism. “Like other myths,” he says, “both inside and outside the church, the myth of “evil evolution” is perpetuated by the masses who are unfamiliar with information which refutes such falsehoods.” He proposed that the popularity of Dialogue, Sunstone, and the growth of LDS websites would leader to greater acceptance of evolution. Twenty years later, I think it remains to be seen.

Next is David Bailey, “Mormonism and the New Creationism.” You’ll remember Bailey’s 1996 article on the past, present, and future of Mormonism and science. In this article in the special 2002 issue, Bailey looks more specifically at “creation science,” the development of views in conservative religous circles that sought to make creationism compatible with evolution and to do so with a claim to scientific, rather than dogmatic, arguments. He discusses surveys about LDS attitudes, including the strong prevalence of antievolutionary views even among BYU students. Nearly 50% of BYU first year students in Bio 101 surveyed denied that evolution happened to humans. 29% of seniors in zoology classes at BYU agreed. The scientist professors surveyed accepted eovlution, but huge numbers of faculty in BYU Religious Education decried it. That department—then still home to Joseph Fielding McConkie, the hier of the Fielding-Smith/McConkie legacy—was a stronghold of fundamentalism continuing at least into the early 2000s.

Bailey’s article traces out this history even more, showing how Joseph Fielding Smith relied on the work of creationists in developing his own ideas, proving that antievolution teachings were borrowed from other christians. He looks at other creationist, creation science, and young earth creationist books published, providing a good survey of the culture of these writings and how they influenced LDS writers. He also summarizes some of their key arguments and provides a scientific assessment of their validity.

Finally, in this 2002 issue is “The Human Genome Project, Modern Biology, and Mormonism: A Viable Marriage?” by Devyn M. Smith. Smith’s article walks through DNA studies and the mapping of human DNA that was completed with the Human Genome Project. It was still ongoing as of the writing of this article. He discusses its importance primarily in terms of pharmacology, ethics, and more. Yet, he notes that almost nothing had been said about this massive scientific adavance by church leaders. “the ethical issues arising from the Human Genome Project are no longer potential scenarios, but very real situations that will occur and are now occurring. It is critical that leaders of the church become aware of these issues before they become acute, so that appropriate responses are considered.” Questions about agency, bodily identity, abortion, and more, are given new data with this project.

Finally, I want to mention a brief personal essay in this 2002 issue by Dynette Reynolds, “Coming Out of the Evolution Closet.” Its a humorous story about her conflicts with members of her Ogden, UT ward, and an experience that probably many members of the church have had about seminary teachers or sunday school teachers making some negative remark about how people who accepted evolution were stupid or evil.

In Spring 2003, David Tolman wrote, “Search for an Epistemology: Three Views of Science and Religion.” This was literally in the issue immediately after the winter 2002 issue on science, so i don’t know if they ran out of room or he didn’t make the deadline or what, but I’m going to include it as part of this time period.

So, these few decades saw a couple of important developments. First, we saw greater historical research on the church’s antievolutionary views. Second, there was a decline in antievolutionary voices in the senior leadership of the church. BYU issued a packet on evolution in 1992 and in the Encyl of Mormonism. Senior church leaders hardly spoke about the topic publicly after that. Yet the old teachings reamined dominant even as they stood alongside denials of any official position. And the intellectual class in the church cointued to try to make room for religious belief and evolution.

Act IV: Recent Treatments

This final act begins in 2006, just a few years after the last one ended, not necessarily because there was any major shift in approach–in fact we have seen a lot of consistency in this century long struggle—but because i had to end somewhere. And in the last 15 years it seems Dialogue has only published two articles that I could find on evolution. In a way, that’s not so bad. The issues havne’t really evolved much—pun intended. Except these last two articles really do raise some new theological questions.

In 2006, Kent C. Condie publishes “Premortal Spirits: Implications for Cloning, Abortion, Evolution, and Extinction.” This is a really interesting article that comes at the issue of evolution not from the perspective of creationism or biblical authority, but rather from the distinctive LDS teachings of premortality. What is the relationship between the premortal spirit and the genetically produced body? How does free agency match up to genetic contraints? Don’t genes imply the heresy of predestination or determinism? Condie proposes some solutions to these problems by suggesting that specific spirits aren’t necessarily predestined to inhabit specific boides. This addresses the issue of cloning and abortion as well, not to mention evolution! So, Condie supports the idea of a created spirit, rather than an eternal one, and a more generic spirit that doesn’t have to be predestined to anticipate every single genetic development of thousands and thousands of generations.

The final article is Spring 2010, famed scholar and author Steven Peck, “Crawling Out of the Primordial Soup: A Step Tward the Emergence of an LDS Theology Compatible with Organic Evolution.” Peck is an evolutionary biologist at BYU. This article asks an even more profound question about evolution. He goes specifically to the heart of the question, not about the compatability of a divinely guided evolution, but about the ethics of such a view. Isn’t the god of such a theology pretty brutal in his direction of nature to produce the current results? What other theological ideas does evolution challenge, besides creationism? This essay looks at a number of what it calls “sticking points” in compatabalism. So, this essay is really theological, exploring the problems that evolution raises from several different theological perspectives, atemporal theism, temporal theism, eschatological theism, and more. Peck puts forward what he calls “Mormon Evolutionary Theology.” This draws on hisrtorical attempts to reconcile evolution and LDS thought, going back to the 1911 BYU professors, John Widtsoe, BH Roberts, and James E. Talmage. But Peck also discusses those ethical issues, natural evils, he calls them, that seem to be implied by the idea of an intelligent designer. Instead, Peck draws on ideas in contemporary LDS theology that limit God’s role in the human drama, including limiting his power as designer. This arises as a solution to the problem of evil as well. “To me, evolution is an empowering idea. Linking it to our theology provides answers to several perplexing questions. It suggests that there is something wonderfully important about embodiment and why physical access to the universe is so important. Our doctrines, informed by evolution, answer questions about why such a cruel and wasteful process was chosen for creation and resituate the problem of evil. I find easy adaptations to our most important and profound doctrines. I see no reason why Mormons cannot, fully and without apology, embrace Darwinian evolution.”

It seems to me that we end in a truly new place. Peck provides a framework for a full, if long, long, delayed theological assessment of Mormonism in light of evolution. We aren’t just hand wringing about it anymore, or writing the history of how we got ourselves into a creationist quagmire, but truly seeing scholars engage wholeheartedly with evolution, including giving up intelligent design.

Since 2010, I couldn’t find another article on evolution in Dialogue. Perhaps that is a good sign in a way, that the force of the issue has died down. It seems less urgent now. Still, that transformation is interesting and holds a lesson I think. Sometimes these tough issues take decades, if not generations, to work themselves out, or at least to a stalemate. BYU professors aren’t getting fired anymore, or facing serious opposition. Dialogue isn’t getting letters to the editor decrying evolutionary ideas. If Duane Jeffery represented the beginning of our journey with evolution in Dialogue, and Steven Peck our ending point, we also see that the nature of the questions have changed as well, as well as the theological sophistication of the answers. Still, though I’m pleased that this once contentious issue is a little less so, I can’t help but hope to see more. We certainly don’t have all the answers, but the questions sure are compelling.

All Episodes

All Episodes