Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith's Theology

Dialogue has a rich and long history covering Mormonism’s founding prophet Joseph Smith.

Joseph Smith’s teachings and the development of Mormon theology have had a lasting impact on religious and cultural history. Exploring the curated topics below can provide a more detailed understanding of different perspectives and scholarly discussions on Joseph Smith’s life, teachings, and historical context.

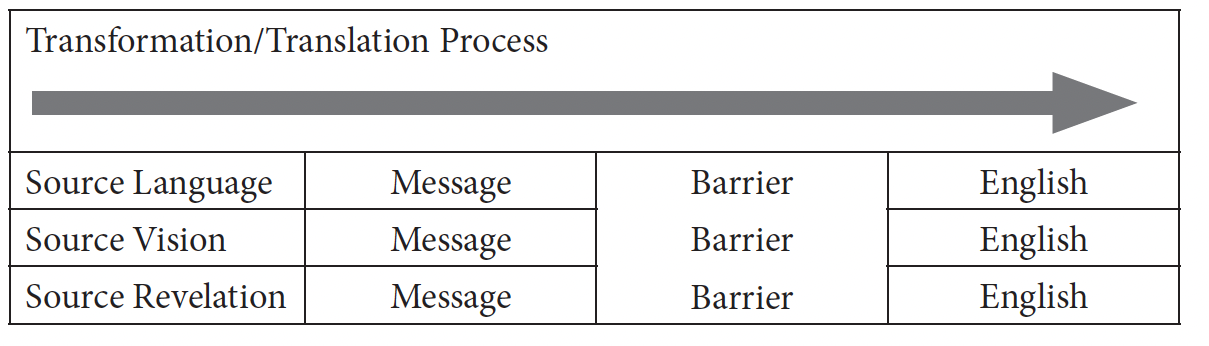

A Reflection on Joseph Smith’s Restorationist Vision of Truth

Ryan D. Ward

Dialogue 55.2 (Spring 2022): 93–102

The way of viewing truth in the Church differs from the common philosophical concept of truth as something that corresponds to the historical or present facts of a given situation.

“Truth, the sum of existence . . .”

—John Jaques, 1851[1]

The way of viewing truth in the Church differs from the common philosophical concept of truth as something that corresponds to the historical or present facts of a given situation. The Church’s version of truth is that it is something possessed by God, it never varies, is eternally fixed, and is made known to humankind through revelation.[2] This absolute view of truth is problematic because it is open to being used by those in positions of power and influence to manipulate and oppress others. Everyone is familiar with the colloquialism “history is written by the victors.”[3] This statement conveys the way that the concept of truth has been manipulated and used to oppress throughout history. The damage and trauma is littered across generations, from the ruthless persecution of so-called heretics after the adoption of Christianity as the religion of Roman empire to the Spanish Inquisition, from the Crusades to the witch hunts, from the massive slaughter, enslavement, exploitation, and oppression of Indigenous peoples throughout the world sanctioned by Christian colonizers to the use of theological and scriptural “truth” to oppress and marginalize women and other vulnerable groups throughout history and into the present day.

In some cases, the concept of absolute truth is used to explicitly oppress and exploit in the name of religion. But more often, this view of truth leads to an inadvertent discounting or marginalizing of alternative views and groups. Due to the specific gender, racial, and cultural makeup of Church leadership, some groups or issues may not be addressed or considered. At an institutional level, religious organizations, including our own, may dictate acceptable positions, doctrinal beliefs, and practices and levy penalties for nonconformity. Those with different experiences who criticize or openly challenge official teaching or narrative can be subject to informal ostracization or formal ecclesiastical discipline. Thus, tight control is maintained over the interpretation and verification of truth by leaders, and the degree to which personal experience and opinion may be held to correspond to the truth is circumscribed. Because an absolute notion of truth is vulnerable to misuse and abuse, what is needed is a way to incorporate individual, varied, and diverse human experience into our understanding and conceptual view of truth.

Truth Revealed Anew

On May 6, 1833, following the summer adjournment of the School of the Prophets in Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith received a revelation that was to become section 93 of the Doctrine and Covenants. The revelation taught that all humankind existed in the beginning with God and Christ as intelligences—autonomous agents organized by God: “Man was also in the beginning with God. Intelligence, or the light of truth, was not created or made, neither indeed can be.”[4] In the very next verse comes a startling pronouncement which forms the basis of my exploration: “All truth is independent in that sphere in which God has placed it, to act for itself, as all intelligence also; otherwise there is no existence.”[5]

There are three important aspects of the verse to consider: 1) truth is independent, 2) truth is an autonomous agent able to act for itself, 3) existence itself depends on this independence and autonomous agency.

Truth as an Independent Agent

For truth to be independent suggests that it exists outside of God’s control. It has not been created, neither can it be, according to verse 29. God is able to place it in a specific sphere, but, once placed, it functions as an autonomous agent that acts outside of God’s control. Aside from this verse, there is no further mention of the independence of truth anywhere in the scriptures. Teaching and interpretation of this concept by Church leaders often mentions this verse as indicative of the fact that there is absolute and relative truth.[6] Absolute truths cannot be changed, whereas relative truth refers to facts that someone discovers that are not veridical statements of reality but approximations that change with further inquiry, experience, and revelation.[7]

Absolute truths are here referred to as the unchanging reality of God’s relation to the world—even if people do not believe, they are still true. But it is unclear how this type of “truth” stands independent of a creator of the world to which it applies and by which it is circumscribed. Furthermore, according to Alma, God is also subject to eternal laws that must be obeyed or he will “cease to be God.”[8] This presents a conundrum in that it is unclear how laws that stand outside of God and to which he is subject could be “placed” anywhere by him, as is clearly stated in verse 30. For these and other reasons, truth here being independent does not seem to refer to an absolute truth of God or the universe that remains unchanging and unchangeable for eternity.

The fact that truth is referred to here as an autonomous agent that can act for itself has more scriptural and doctrinal parallels within our theology.[9] The doctrine of agency is critical to our understanding of the purpose and meaning of the existence of humanity. The interpretation that truth is placed by God in a sphere to act for itself is consistent with foundational Mormon teachings about agency and supports interpreting verse 30 as indicating that truth is crucially related to embodied mortal experience.

Truth as the Action of Embodied Humanity in History

If we consider embodied human beings as a critical aspect of truth, our understanding of truth necessarily has to be informed and conditioned by the critical and varied aspects of human existence. The embodied nature of our existence means that each individual will live out their lives in different places, countries, cities, and are subject to different life experiences, opportunities, and challenges as a function of their particular state, including the impacts of gender, race, and ethnicity, along with cultural, economic, political, and other factors. If embodied human existence constitutes truth, then truth must encompass the range of experiences, perspectives, choices, consequences, and life trajectories of all humanity. Truth was placed in the world as embodied humanity in all its infinite diversity and continues to be truth as we grow and act as agents throughout our lives.

To clarify, truth can be defined as the action of embodied humanity in history. As such, truth in the world is ever evolving and becoming. Verse 24 says that truth is “knowledge” of things as they are, and were, and are to come. I take this to mean that knowledge of these things comes through experience, either personally or through the works and words of others, or through divine gift of understanding the realities of human experience throughout history. In experiencing, we come to know the truth of human existence. Truth is, in actuality, things as they have been, are, and will be.[10] For individuals, then, truth constitutes knowledge of human action in history. From an omniscient perspective, truth is the actual, ongoing action of humanity in history.

Jesus as the Truth

Because truth cannot be separated from individual human experience, only one who fully experienced what all of humanity experienced could claim to understand and comprehend all truth. In section 88, Joseph revealed how Christ’s atonement and condescension into mortality had granted him such comprehension: “He that ascended up on high, as also he descended below all things, in that he comprehended all things, that he might be in all and through all things, the light of truth.”[11] Now we begin to understand what Jesus means when he refers to himself as “the truth.” His life in mortality, surrounded by the suffering of the poor, oppressed, and marginalized, already had allowed him to “bear witness unto the truth.”[12] Furthermore, one interpretation of this view is that Jesus’ solidarity with humanity through his incarnation and atonement enabled him to experience all that embodied humanity had, would, and will experience. When Jesus personally experienced in mortality the sum total of human experience, he quite literally became the totality of truth.

Another interpretation that is consistent with the view of truth proposed here is that in calling himself the truth, Jesus was explicitly referring to his mortal embodiment. According to this view, Jesus was truth in the same way that embodied humanity is truth. By referring to himself as truth, Jesus affirmed this central characteristic of the truth of humanity. Although this idea may seem unfamiliar to many members of the Church, it has a long historical and scholarly tradition. At issue is the meaning of the phrase “son of man,” which appears numerous times in the Bible. The translation of the phrase from Hebrew and Aramaic indicates that it was a colloquial way of referring to a generic human being, or humanity generally, but with a specific contrast to deity in its emphasis on the mortal condition.[13]

Why would Jesus refer to himself in this way? Why not refer to his own divinity, or use the other names that have become common for him: Savior, Redeemer, Lord, Messiah? In fact, at every opportunity to embrace these titles, Jesus rejected them, preferring this diminutive generic term for humanity. The revelation by Joseph Smith that Jesus grew from “grace to grace” and “received not of the fullness at first”[14] suggests that he may have been unaware of his purpose and mission for a time. One might assume that once awareness struck, he would begin referring to his divinity, but this does not happen. There seems to be something very important to Jesus about his mortal embodiment and humanity in general. The view of truth taken here suggests that it was Jesus’ humanity that made him the truth, not his divinity. His referral to himself as “son of man” seems to indicate that he recognized the truth of his embodied mortal action as a part of the ongoing truth of humanity acting in history.

God’s Glory as Truth

We understand the purpose of this life as being to demonstrate that we can keep God’s commandments, make and keep sacred covenants by receiving saving ordinances, and become progressively sanctified through the atonement of Christ. A succinct statement of this is given in the book of Moses: “For behold, this is my work and my glory, to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”[15] Here we find ourselves at loggerheads regarding what to make of a scriptural term that is used in multiple different ways. Specifically, what exactly is referred to here by God’s “glory”? At various times in the scriptures, “glory” refers to worldly fame and accolades,[16] heavenly blessing and favor,[17] exultation,[18] aesthetic beauty,[19] brightness,[20] fullness of life in the world to come,[21] and an enabling power,[22] among other things. Later in the revelation in section 93, Joseph gives as succinct a definition of God’s glory as we get in scripture, yet when considered with the view of truth explored above, it provides a key to understanding God in relation to humanity and why human existence and experience as truth is crucial to God: “The glory of God is intelligence, or, in other words, light and truth.”[23] Up until now in the revelation, Joseph has played loosely with these three terms: intelligence, light, and truth. Here he clarifies for us that intelligence, light, and truth are synonymous. Not only that, they are the glory of God. When considered in conjunction with the interpretation of truth explored above, we can interpret this verse to mean that the glory of God is the perpetual and ongoing truth being lived out in and through embodied humanity.

This definition of glory helps us make sense of Moses 1:39 in context. The way we usually read this verse is that God’s work and glory, everything that he does and the crowning achievement of his being, is to bring to pass our immortality and eternal life. But this verse comes at the end of Moses’ vision of the creation and the natural and human history of the world.[24] God has here shown Moses all of the earth’s existence and inhabitants, the whole of the natural history of the earth. He has also intimated that there are numberless other worlds and inhabitants that he has created. It is at the end of this spectacular vision that verse 39 comes. God seems to be saying that the driving force in all of creation, including humankind, is to progress toward a state of godliness. Everything that has happened, everything that is happening, and everything that will happen, is moving toward that final end. God’s glory is creation and humanity in action in history. Because this theology considers all of our experience in mortality as helping us to become like God—indeed, gods in our own right—we can therefore view God as the potentiality of humanity and creation. As such, God’s glory is necessarily incomplete and ongoing and will not be realized fully until all humanity and creation lives out the totality of its existence. As long as there is an ongoing creation that acts with agency, God’s truth and glory will continue to deepen and expand.

An Expanded Restorationist View of Truth

The view of truth as the action of embodied humanity in history cannot accommodate an interpretation of truth that includes anything less than the totality of human existence and experience. According to the current interpretation, God cannot create truth because truth is independent of God. He organizes it in creation, and it acts for itself. It is therefore not possible for any organization or religious tradition to hold either more or less truth than any other, any more than it is possible for God to create truth. This means that God also does not dictate what is true and what is not because truth is a function of embodied human experience. Intelligence, cloaked in mortal humanity, acts with agency, and this is truth. It is not something that can be revealed, verified, or witnessed to, at least not in the sense we traditionally think of. It is simply the ongoing action of humanity in history.

Rather than being a form of relativism or pointing to the belief that all truth claims are equally valid and therefore we can believe and act however we will, this position claims that truth, as understood by individuals, is incomplete because it forms only a part of the total truth as comprised by human existence. Therefore, it makes no sense to compare one “truth” to another because the sum total of all truths being lived out individually and in relation is the full truth. Thus, this view subsumes relativism within a totality of truth that is ongoing, continuously changing, and being realized in the lived experience of humanity.

Our faith tradition claims to accept all truth wherever it may be found, yet we often view and portray ourselves as holding a strict monopoly on truth. The interpretation explored here suggests that such claims are incompatible with the fundamental nature of truth as an independent agent. Thus, for our tradition to encompass all truth, we would need to recognize, accept, and claim all human experience as the ongoing truth of God. The challenge of our missionary and other efforts would not be to determine and decide how most successfully to convert others to our faith but instead how to understand and experience our lives within our covenant community in light of, and in relation to, the ongoing truth around us in our communities, cities, nations, and the world.

Within our congregations and pews, we would feel less threatened and more empowered by the diversity of experience and perspective of our members. Historically oppressed groups, such as women, racial groups, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other minorities, would be given respected places in our conversations and efforts. We would recognize that prevailing views, understandings, and treatment of some groups and individuals have been conditioned by a long history of the normalization of their marginalization and oppression in society. Failure to acknowledge this, coupled with a position on truth that denies the reality of the truth of all unique existence and experience, has amplified marginalization in our faith tradition and theology. Recognizing all lived experience for the truth it is would help us to embark on the long-needed and painful journey of justice and reconciliation. Such reconciliation would allow our faith tradition to more fully reflect and embody the full majesty and beauty of the glory of God manifest in the ongoing truth of the lived experience of humanity. I believe that the seeds of a more universal, expansive, and inclusive vision of truth were revealed, however fleetingly and opaquely, to Joseph Smith in this brief but magnificent verse. Perhaps reflections like this one can contribute to the recovery and further imagination, development, and articulation of this unique and powerful restorationist concept of truth.

[1] From “Truth,” a poem included in the first edition of the Pearl of Great Price. It was later set to music by Ellen Knowles Melling, titled “Oh Say, What is Truth?,” and included in the LDS hymnal as no. 272.

[2] Doctrines of the Gospel Student Manual, Religion 430 and 431 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2010), chap. 1.

[3] This statement is generally attributed to Winston Churchill, although this claim is unsubstantiated.

[4] Doctrine and Covenants 93:29.

[5] Doctrine and Covenants 93:30.

[6] Spencer W. Kimball, “Absolute Truth” (devotional address given at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, Sept. 6, 1977).

[7] D. Todd Christofferson, “Truth Endures” (address to CES religious educators, Salt Lake Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Utah, Jan. 26, 2018).

[9] 2 Nephi 2:13–26; 2 Nephi 10:23; Alma 12:31; Helaman 14:30.

[10] This notion of truth parallels the thought of Hegel, who asserted that to truly know something was to know its past, present, and future state. All present “truth” is but a snapshot of the “absolute” or “totality” of truth that is becoming. See Georg Hegel, The Science of Logic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015; first published in German in 1812). Similarly, Harold Joachim’s “coherence” theory of truth suggests that something is true to the extent that it coheres with the character of a more significant “whole.” For Joachim, there is only one “truth,” and individual judgments or beliefs are only true “to a degree.” See Harold Joachim, The Nature of Truth (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977; first published in 1906).

[11] Doctrine and Covenants 88:6.

[13] Restoration scripture has been interpreted as indicating that the name is another title for the Savior. See Doctrine and Covenants 45:39; 49:6, 22; 58:65; Moses 6:57.

[14] Doctrine and Covenants 93:13.

[16] Proverbs 25:27; Matthew 4:8; 6:2; John 7:18; 1 Thessalonians 2:6; 1 Peter 1:24; Doctrine and Covenants 10:19; 76:61.

[17] 1 Samuel 4:21; Psalm 8:5; 62:7; 84:11; Proverbs 4:9.

[18] Psalm 149:5; Jeremiah 9:24; 1 Corinthians 3:21; James 3:14; 1 Peter 1:8; 2 Nephi 33:6; Alma 26:16.

[20] 1 Corinthians 15:41; 2 Corinthians 3:7; Doctrine and Covenants 76:70.

[21] Proverbs 4:9; 2 Corinthians 4:17; Colossians 3:4; 1 Timothy 3:16; 1 Peter 5:1, 4, 10; 2 Peter 1:17; Alma 14:11; 36:28; Doctrine and Covenants 6:30; 29:12; 58:3; 66:2; 75:5; 76:6; 101:65; 104:7; 124:17; 130:2; 132:19; 133:32; 136:31; Moses 6:59; 7:3; Abraham 3:26.

[23] Doctrine and Covenants 93:36.

[post_title] => A Reflection on Joseph Smith’s Restorationist Vision of Truth [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 55.2 (Spring 2022): 93–102The way of viewing truth in the Church differs from the common philosophical concept of truth as something that corresponds to the historical or present facts of a given situation. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => a-reflection-on-joseph-smiths-restorationist-vision-of-truth [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2024-01-28 18:43:08 [post_modified_gmt] => 2024-01-28 18:43:08 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://dj.slanginteractive.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=30132 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Was Joseph Smith a Monarchotheist? An Engagement with Blake Ostler’s Theological Position on the Nature of God

Loren Pankratz

Dialogue 55.2 (Spring 2022): 37–72

Joseph Smith’s teachings on God found in his preaching at the April 7, 1844 general conference, known as the King Follett Sermon, and Smith’s Sermon in the Grove, given at a meeting held just east of the Nauvoo Temple on June 16, 1844, have appeared to many to give strong support to this view. There, he taught that God was not always God but developed into God over time.

Many members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints hold a view of God in which “God became ‘God’ at some first moment through obedience to moral principles that were given by a prior god, the Father’s Father.”[1] This supposition follows the teaching of many erstwhile theologians and authorities of the Church who have understood Joseph Smith to teach that God became God at some moment in the past, having been exalted to his divine stature by another being due to his obedience to eternal laws.[2] Joseph Smith’s teachings on God found in his preaching at the April 7, 1844 general conference, known as the King Follett Sermon, and Smith’s Sermon in the Grove, given at a meeting held just east of the Nauvoo Temple on June 16, 1844, have appeared to many to give strong support to this view. There, he taught that God was not always God but developed into God over time. Eschewing this traditional notion, Blake Ostler defends a view of God in which the head God (the Monarch) leads all other subordinate gods.[3] He argues that this kingship monotheistic view is the proper interpretation of Joseph Smith’s teaching on God. Ostler seeks to harmonize this monarchotheist viewpoint with Smith’s teaching both generally and, more specifically, in the King Follett Sermon and his Sermon in the Grove.[4] Ostler is not just making a theological argument but a historical one about what Joseph Smith’s own views were. This paper demonstrates that Ostler’s monarchotheist construal of Joseph Smith’s teaching is not supported by the evidence.[5]

An 1840 Sermon of Joseph Smith

To be successful, the monarchotheist must reconcile this theological position with the teaching of Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo period and the tradition that developed from it. One of the most important issues is reconciling the notion from classical theology that God is eternal and unchanging with Smith’s idea that God was not always God. Ostler develops an important solution to this that allows him to hold both that God was always God and that God was at one point a human. He argues that Joseph Smith’s teachings support the position that “There was an interval of time from T2 through T3 during which the Father was mortal and not fully divine, but the Father was fully divine eternally prior to T2 and forever after T3.”[6] In this argument, T2 and T3 represent time markers in the life of God. His claim is that while God the Father may not have been fully divine in one period of time, namely that period we can symbolize as between T2 and T3, still he was fully divine both prior to T2 and after T3. In the argument, the time between T2 and T3 is to be thought of as a mortal sojourn of some sort. Thus, Ostler’s contention is that Smith’s teaching is consistent with the view that God the Father was fully divine prior to and following his mortal sojourn. It is Ostler’s contention that this view is consistent with Smith’s later teaching that God was not always God found in the 1844 King Follett Sermon.

Ostler begins his argument for a rereading of the King Follett Sermon that is consistent with the monarchotheist position by first seeking to add context to this position. He points to a sermon Smith preached on February 5, 1840. In this sermon, Smith was preaching in Washington DC, describing his religious beliefs to outsiders.[7] Here Smith taught, “I believe that God is Eternal. That he had no beginning and can have no End. Eternity means that which is without beginning or End.”[8] Ostler admits that this seems to contradict what Smith says in the King Follett Sermon, in which he claims, “for I am going to tell you how God came to be God. We have imagined and supposed that God was God from all eternity. I will refute that idea, and will take away and do away the vail, so that you may see.”[9] There appears to be a contradiction between what Smith taught in 1840, in which God is said to be God eternally, and the 1844 teaching, in which the eternal divinity of God seems to be denied. Ostler’s solution to this seeming contradiction is to argue that, in fact, both of these claims are in harmony with the monarchotheist position and that the 1840 sermon helps one interpret what Smith meant in 1844.

I agree that there is not necessarily a contradiction between Smith’s two statements, but on different grounds from Ostler. Rather than supporting the monarchotheist position, the February 5, 1840 sermon appears to confirm the notion that God has not been fully divine from all eternity. In this 1840 discourse, Smith does not merely claim that God is eternal but also that souls in general are eternal and have no beginning. Just after claiming that God is eternal, having no beginning or end, he said, “I believe that the Soul is Eternal. It had no beginning; it can have no End.”[10] Matthew Livingston Davis, the scribe of the February 5 sermon, understood Smith’s point to be that neither God nor the human soul had a beginning, and they will not have an end.[11] Smith does not highlight an attribute of God in distinction to what is common to humanity; rather, he is claiming that the “soul of man” is as eternal as God is.[12] Thus, rather than setting up a seeming contradiction that needs to be resolved, the 1840 sermon supports the interpretation of Smith’s teaching in which God is thought to have eternally existed (as have all souls) but was exalted to divinity at some point in the past. This sermon shows that Smith, in 1840, taught that humans share God’s same trajectory, at least potentially. Contra Ostler, this sermon does not show that Smith taught that God was divine from all eternity. There appears to be no conflict between Smith’s 1840 sermon and his later teaching on God as understood and espoused historically by Church theologians and authorities. Having addressed this preliminary matter, I now turn to Ostler’s specific interpretations and revisions of Smith’s King Follett Sermon.

The King Follett Sermon

At the April 1844 general conference, Joseph Smith delivered a funeral oration for a man named King Follet to a crowd of Latter-day Saints estimated to be around twenty thousand in number.[13] This sermon, known as the King Follet Sermon (KFS), has become one of his most important theological discussions. In that sermon, Smith preached,

It is the first principle of the Gospel, to know for a certainty the character of God, and to know that we may converse with him as one man converses with another, and that he was once a man like us––yea, that God himself, the Father of us all, dwelt on an earth, the same as Jesus Christ himself did, and I will show it from the Bible . . . What did Jesus say? (Mark it Elder [Sidney] Rigdon;) the Scriptures inform us that Jesus said, ‘as the Father hath power in himself, even so hath the Son power’, to do what? Why what the Father did; the answer is obvious, in a manner to lay down his body and take it up again.[14]

It is not part of the historical teaching of the Church that each human was fully divine prior to our mortal life. Thus, when Joseph Smith taught that God was “once a man like us,” he seemed to imply that God had not been fully divine prior to his mortal sojourn. Ostler acknowledges that passages from the KFS, like this one, can be interpreted to support the notion that “there was a time T2 at which the Father first became fully divine, but that he was not fully divine prior to T2.”[15] That is, this passage appears to be consistent with the belief that God, like humans generally, was not fully divine from all eternity, and that he was later exalted to his present fully divine stature after being resurrected from the dead. This interpretation is also consistent with the belief taught in 1840, that the Father, like all souls, has always existed without beginning and will always exist without end. However, Ostler moves the discussion of this passage in a different direction. He claims that “it is uniformly taught in Mormon scripture and by Joseph Smith that Christ was a fully divine person prior to mortality.”[16] Ostler reads the KFS to support the view that the Father was fully divine prior to his mortality. He claims that “the Father’s mortal experience was like Christ’s, and thus it is more consistent to interpret Joseph Smith to assert that the Father, like Christ, was divine before his mortal sojourn.”[17] Ostler’s contention is that the above passage of the KFS only teaches that there was a time (i.e., during his mortal sojourn) when God was not fully divine, while remaining open to the possibility that God was fully divine prior to that time. He bases this on his understanding of Jesus as being in possession of all the essential properties of divinity prior to his mortal life.

This interpretation seems far from secure. First, Smith is claiming that there is something Jesus has in common with the Father, not something the Father has in common with the Son. He is pointing out specifically that just as the Father had the power to lay down his body and take it up again, so the Son has the power to lay down his body and take it up again. This comparison says nothing of God’s ontological status prior to his mortal life. The KFS is aimed to give comfort to those grieving the loss of a beloved member of the community. This funeral sermon provides hope for those who have not been divine from all eternity by teaching that they can follow the example set by God and Jesus. Smith claims that both the Father and Jesus laid down their lives and were later exalted, and in this sermon he extends that hope to all humans generally. Ostler takes this quotation from the KFS to mean that if Jesus was divine prior to his mortal life then God was divine prior to his. However, logically speaking, Jesus’ claim to follow the Father’s example does not necessarily imply that the Father was fully divine before his mortal sojourn, even if Jesus was fully divine before his mortal existence. When predicating some distinctive attribute of person A to person B, one is not thereby committed to predicating some other feature of person B to person A. The passage does not say that what is true of Jesus is also true of the Father. Rather, it only claims that what is true of the Father is true of the Son. Thus, Ostler’s contention that this passage implies that the Father was fully divine prior to his mortal life is not substantiated.

Secondly, Ostler’s interpretation of this passage from the KFS, if correct, disproves his main point. While it may have been uniformly taught in Mormon scripture and by Joseph Smith that Christ was a fully divine person prior to mortality, it is also taught that there was a time when Jesus was first exalted. That is, Jesus was the firstborn spirit child of God in the premortal existence and progressed to divinity. For example, in the winter of 1834–35, lectures were given in Kirtland, Ohio that served as an early attempt to “formulate a systematic Latter-day Saint theology.”[18] These lectures were published in the Church’s newspaper in May of 1835, and “All seven lectures were published together later that year in the first edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, the lectures constituting the ‘doctrine,’ and Joseph Smith’s revelations, the ‘covenants.’”[19] While it is debated whether or not Joseph Smith personally delivered all of the lectures, the “inclusion of the lectures in the Doctrine and Covenants in 1835 strongly suggests that Joseph Smith approved of the content of the lectures.”[20] These lectures have been said to represent the “breadth and depth of the mind of Joseph Smith.”[21] “Lecture Fifth” of the Lectures on Faith teaches that Jesus, having overcome, “received a fullness of the glory of the Father.”[22] Later, in “Lecture Seventh” of the Lectures on Faith, it is taught that Jesus Christ is the prototype of a saved and glorified person. He is the example for us to follow, a person who, through faith, “has become perfect enough to lay hold upon eternal life.”[23] This early summary of the theology Joseph Smith developed depicts Jesus advancing from having a non-deified status to being one who takes hold of eternal life, having received a fullness of glory. Thus, even if Christ becomes the archetype of pre- and post-mortal divinity, his trajectory also includes an initial progression to divinity. There was a time, call it time T, when Jesus was not fully divine. Then at T1 he was exalted, then at T2 he was mortal (and not glorified), and then at T3 he was full of glory once more. Ostler has argued that the KFS passage above is consistent with monarchotheism because Smith claimed that Jesus did only what he had seen the Father do before him, and since we know that Jesus was fully divine prior to his mortal sojourn, then God must have been fully divine prior to his subsequent exaltation as well. However, the trajectory of Jesus represented in the KFS and in the Lectures of Faith appears to be one of a being who was exalted at some time after he was born of heavenly parents. If Ostler is correct in his interpretation and Jesus follows the Father’s path, then this would imply that God the Father was once a mere organized being who was later exalted, after which he became mortal and then, finally, was glorified again. Thus, if Ostler is correct, God the Father still has not been God from all eternity. Ostler’s treatment of the passage from the King Follett Sermon does not work to effectively undermine the understanding of many members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who hold that “God became ‘God’ at some first moment through obedience to moral principles that were given by a prior god, the Father’s Father.”[24]

There is a second key passage in the King Follet Sermon that seems to establish the notion of a progression toward deity. Smith preached,

Here, then is eternal life—to know the only wise and true God; and you have got to learn how to be Gods yourselves, and to be Kings and Priests to God, the same as all Gods have done before you, namely, by going from one small degree to another, and from a small capacity to a great one; from grace to grace, from exaltation to exaltation until you attain to the resurrection of the dead, and are able to dwell in everlasting burnings, and to sit in glory as do those who sit enthroned in everlasting power.[25]

Ostler concedes that this passage may indicate that persons “learn how to advance to become Gods by becoming a ‘god’ at some first time T1 by advancing from one capacity to another until they reach the status of gods.”[26] However, Ostler seeks to reconcile this with his own view of a static and unchanging divine status. He argues that readers should not assume “that those engaged in the process of learning to be gods cannot already be gods.”[27] Ostler claims this passage should be taken to mean only that “God the Father has been in a process of eternal progression from one exaltation to another for all eternity, and humans can commence to progress toward godhood by engaging in the same activity of progression.”[28]

Contrary to Ostler’s interpretation, this passage is aimed at communicating to mortal humans, who have (presumably) never been gods, how they may progress to “be Gods yourselves.” Humans, who at present have never been fully divine, may become so by following the same process “as all the Gods have done before” them. Smith taught humans to take as their model for exaltation other beings who have learned little by little how to progress from a small capacity to a great one. He is not talking about a separate class of eternally divine beings. Even “the only wise and true God,” in Joseph Smith’s theology, does not appear to be exempted from this mimicable process. “All Gods,” Joseph Smith explains, have followed this trajectory. The above passage is all the more remarkable because in the sermon, just prior to the quoted passage, Smith led the congregation to consider what God is like. He petitioned his listeners, “I want to ask this congregation, every man, woman and child, to answer the question in their own heart, what kind of a being God is,”[29] and Smith takes it as his “first object” to “find out the character of the only wise and true God; and what kind of being he is.”[30] The portion of the KFS quoted above is Smith’s answer to this question. What sort of being is the only wise and true God? He is a being who has learned to be God, advancing from one capacity to another, as all gods have done. Ostler’s contention does not fully consider the context and aim of the sermon.

There is a third passage in the KFS that Ostler has opened for reinterpretation. In the most well-known version of the King Follett Sermon produced by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Joseph Smith states:

It is necessary we should understand the character and being of God and how He came to be so; for I am going to tell you how God came to be God. We have imagined and supposed that God was God from all eternity. I will refute that idea, and take away the veil, so that you may see.[31]

In this passage, Smith reportedly refutes the idea that God “has always been God or always had divine status.”[32] Here again, he put forward the idea that God “came to be” at a certain point, indicating that divinity occurred at a particular time.

Ostler’s strategy with this passage is to argue for a revision of the text that will allow for a different interpretation. There exists no stenographic record of this sermon. Instead, what we have are a number of individuals’ notes of the sermon. Several of these accounts were scribes from Smith’s presidential office and other authorities of the Church, making this the best recorded of Smith’s discourses.[33] Ostler’s primary argument maintains that the above statement, while supported by Willard Richards’s and Wilford Woodruff’s recollection of the sermon, is not in harmony with Thomas Bullock’s report of the discourse.[34] Ostler also points out that another observer of the address, William Clayton, omits the statement “about a refutation altogether.”

However, one should accept the traditional text as published by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for three reasons. First, William Clayton’s report does convey that Smith claimed to “tell you how God came to be God.”[35] While he does not reproduce the exact phrase as Willard Richards and Wilford Woodruff, he does produce the same teaching. Presumably, for Smith to tell us how “God came to be God,” he will have to refute the idea that God has been God for all eternity.

Secondly, there is actually another version of the sermon that reports the same idea. Samuel W. Richards’s record is brief but remarkably records Smith’s refutation that God has been God from all eternity. It states, “to have eternal life, God: a man like one of us, even like Adam. Not God from all Eternity.”[36] Richards’s account provides another witness to Smith’s refutation of the notion that God has been God from all eternity, making it difficult to maintain, as Ostler does, that Smith did not teach this.

Thirdly, Bullock’s account is not out of harmony with Willard Richards’s, and Wilford Woodruff’s account as Ostler claims. Bullock’s report records, “I am going to tell you what sort of a being of God. for he was God from the begin of all Eternity & if I do not refute it.”[37] Ostler claims that Bullock’s report states that Smith does not intend to refute the idea that God has been God from all eternity. However, Bullock’s report is ambiguous, as he reports Smith to have said only, “if I do not refute it.” He does not say “I do not refute it.” The statement as recorded by Bullock could well be understood as shorthand for something like, “& [see] if I do not refute it.” Supporting this notion, Bullock notes that just after this statement, Smith went on to claim that “God himself the father of us all dwelt on a Earth same as J C himself did.”[38] This seems to refute the idea that God has been God from all eternity. God dwelt on an Earth, and during that time God was not fully divine. Bullock’s notes continue that humans have this capacity to dwell on an Earth and be exalted to divine status as well, claiming “you have got to learn how to be a God yourself & be K[ing] & Priest to God same as all have done by going from a small cap[acit]y to an[othe]r. from grace to grace until the res[urrectio]n. & sit in everlasting power as they who have gone before & God.”[39] The theology Bullock records, that God and all humans share a trajectory of progress, is entirely in line with the one reported by Richards, Woodruff, and Clayton. Ostler’s interpretation of this passage from Bullock’s report would set it against not only the other records of the discourse but against Bullock’s own account.

The idea that there is a disagreement between Bullock and the other witnesses on this point is weak. Bullock himself was responsible for preparing the minutes of the conference based on his and William Clayton’s notes.[40] These minutes were then published in Times and Seasons. In Bullock’s published minutes, Smith claimed, “We have imagined that God was God from all eternity,” but that it is necessary to “understand the character and being of God, for I am going to tell you how God came to be God.”[41] The preponderance of the reporting seems to point in one direction: namely, the interpretation Ostler seeks to avoid.[42]

As a final consideration regarding the view of God found in the King Follett Sermon, Ostler points to Smith’s reconstruction of Genesis 1:1 as proof of his monarchotheistic leanings. Smith claimed that Genesis 1:1 should be read to say, “The head one of the Gods brought forth the Gods.”[43] Ostler claims that Smith’s revision of Genesis 1:1 “entailed that there is a single God who is the head of all other gods.” As has been argued elsewhere, Smith used Hebrew “as he chose, as an artist . . . in accordance with his taste, according to the effect he wanted to produce, as a foundation for the theological innovations.”[44] In Kevin Barney’s study of Smith’s emendation of the Hebrew behind Genesis 1:1, he admits that it is difficult to piece together Smith’s exact logic in his reconstruction. Rather than attempting to follow Smith’s interpretation of the text of Genesis 1:1, Barney concludes that it seems more fruitful to interpret Smith as conjecturing that the original Hebrew of Genesis 1:1 had been altered and that his reading was the original.[45] While it may be difficult to ascertain how Smith arrived at his reconstruction of Genesis 1:1, Barney claims that the basic thrust of Smith’s argument is not as uncertain. Joseph Smith appears to make the claim that Genesis 1:1 is describing the council witnessed to in the book of Abraham 3:23, in which God called other gods to council in order to create our world. This certainly does not necessitate God’s being fully divine from all eternity, as God could have been fully divine at this point in his existence and could be the head God of this creative event. This is fully consistent with the belief that God was not fully divine from all eternity. Ostler contends that Smith “believed that the text of Genesis 1:1 had been corrupted and that it originally indicated that the head God brought forth the other gods in a council of gods.”[46] This claim will be revisited in the next section while reviewing Ostler’s claim regarding Smith’s use of Genesis 1:1 in the Sermon in the Grove.

Sermon in the Grove

Joseph preached his final sermon in a grove east of the Nauvoo Temple.[47] He began the sermon by quoting Revelation 1:6, “And hath made us kings and priests unto God and His father.”[48] The King James Version of the Bible places “and His father” after “God,” which Joseph Smith took to mean that the verse was stating that Jesus makes Christians to be kings and priests under God the Father and God the Father’s father. This understanding seems to have been seized upon by Joseph Smith and used as a proof text from which to proclaim that “the Father had a father and that there is another ‘Father above the Father of Christ.”[49] In this view, God the Father of Jesus Christ also has a father.

Ostler believes that the Father of God here refers only to his earthly existence. He explains, “when the Father condescended from a fullness of his divine state to become mortal, he was born into a world and had a father as a mortal.”[50] Ostler begins his defense of this interpretation by noting that Smith continues to stress that Jesus does “precisely” what the Father did before him.[51] As we saw above, this strategy fails to suit Ostler’s purposes because, if the analogy holds, it proves too much. If Jesus truly follows the Father’s precise example, then the example is that of a person of divine parentage who became divine, entered into mortality, and exercised power to take his life up again after death. If Jesus’ divine Father was the trailblazer of this precise path, then he too would have both a spiritual and mortal father.

Ostler puts forward other evidence for his reading of this sermon in support of monarchotheism. He points to George Laub’s journal notes from this sermon. Ostler quotes Laub as reporting that “the Holy Ghost is yet a Spiritual body and waiting to take upon himself a body, as the Savior did or as god did.”[52] Ostler concludes from this that “Joseph Smith taught that already divine persons, including the Son and the Holy Ghost, take upon themselves bodies.”[53] The major problem with this use of George Laub’s journal is that Ostler’s quotation of this portion of the journal is incomplete. Laub’s sentence continues on where Ostler provides a period. Laub’s record reads, “But the holy ghost is yet a spiritual Body. and waiting to take to himself a body as the savior did or as god did or the gods before them took bodies.”[54] This indicates that Smith taught that all gods follow this path, with Jesus, Jesus’ Father, and the Holy Ghost as exemplars of the pattern. Laub’s notes go on to further extend the analogy: “the scripture says those who will obey the commandments Shall be heirs of god and joint heirs with Jesus Christ. we then also took Bodies to lay them down and take them up again.”[55] Laub’s understanding is that we do just what Jesus did, which is just what the Father did before him, and other gods before him. Laub’s journal provides deeper evidence that Smith’s thinking about God is that the Father, the Son, and we humans are but three links in an eternal chain of gods.

William McIntire’s and Thomas Bullock’s record of Smith’s Sermon in the Grove relates that in this sermon Smith returned again to his modification of Genesis 1:1.[56] Ostler contends that Smith’s understanding of Genesis 1:1 is that a monarchotheistic head God presides over a council of gods.[57] However, in Thomas Bullock’s account of this sermon, Smith understands the term “Eloiheam” from Genesis 1:1 to be translated “in the plural all the way thro––Gods––the heads of the Gods appointed one God for us.”[58] Rather than there being a head God who organizes a council, there is instead an insistence that in the beginning there were heads of the gods who appointed one God for us. Smith proclaims, “Intelligences exist one above anotr. that there is no end to it.”[59] That there is “no end to it” suggests that Smith sees no one head God at the end of the line. He states, “in the very beginning there is a plurality of Gods—beyond the power of refutation.”[60] From Thomas Bullock’s record, Smith is clear, there are a plurality of head gods who appointed one God to preside over the earth. Ostler’s contention that Smith taught there to be one head God does not hold up.

William McIntire’s report of the sermon, though brief, shares Bullock’s understanding of Smith’s use of Genesis 1:1 in the Sermon in the Grove. McIntire claims that in this sermon, Smith “proceeded to show the plurality of Gods” with his explanation of the “origanel [sic] Hebrew” of Genesis 1:1.[61] McIntire claims that Smith shared with the gathered crowd in the grove that the “Head Gods organized the Earth & the heavens.”[62] McIntire’s witness claims Joseph Smith spoke of the “Head Gods” (plural), rather than a singular “head God,” as Ostler would have it. Thus, the reports of Smith’s teaching in the Sermon in the Grove does not support Ostler’s contention that Smith taught there to be a monarchotheist Head God who presides over a council of gods. Smith teaches a plurality all the way through.

Conclusion

Ostler’s interpretation of Joseph Smith’s teaching rests on three principal arguments. First, he claims that Smith’s teaching in the KFS implies that the Father was divine prior to becoming mortal just as Jesus was divine prior to mortality. Yet the KFS was shown to be better interpreted as claiming that God was elevated to his status as God at some time in the past. Further, if we press the analogy between the Father and the Son as Ostler does, the conclusion runs contrary to Ostler’s contention and God the Father is still elevated to divinity from some state of non-divinity at some point prior to his mortal life. Second, Ostler claims that Smith’s teaching that the Father had a father from Smith’s Sermon in the Grove should be interpreted as God the Father’s having a father in mortality, and not that there was a God prior to the Father. After reviewing Ostler’s arguments, it seems clear that Smith’s point in that sermon was indeed to claim that God the Father of Jesus himself had a spiritual progenitor. Third, Ostler argues that Smith’s use of Genesis 1:1 shows that Smith believed in a monarch God who rules over a heavenly council of gods. This is a novel thesis, but as a historical argument it does not hold. The great lesson Smith stresses from his emendation of Genesis 1:1 is that there is a plurality of gods at play from the very beginning. The heads of gods appointed the God of this world to his station. This is a process Smith appears to envision having no end.

Ostler’s contention that the best interpretation of Joseph Smith’s teachings about God is to suppose God to be the head God (the Monarch) who leads all other subordinate gods has not been persuasive. Ostler’s kingship monotheism does not appear to be represented in the two key discourses of Joseph Smith that have been examined in this paper. Instead, the best interpretation of Smith’s teaching on God in those discourses is that God the Father himself had a premortal father and came to be exalted to divinity at some first moment, that Jesus followed God the Father’s example, and that humans may follow Jesus’ example in turn.

[1] Blake T. Ostler, Exploring Mormon Thought: The Problems of Theism and the Love of God (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2006), 91.

[2] Terryl Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 63. See also: Givens, Wrestling the Angel, 60; Parley P. Pratt, Key to the Science of Theology, 4th ed. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1877), 37; John Widtsoe, A Rational Theology: As Taught by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: General Boards of the Mutual Improvement Association, 1932), 175.

[3] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 442.

[4] Portions of this article draw on research from the author’s PhD dissertation. See Loren Pankratz, “Traditional Christian and Mormon Views of God and Their Compatibility with the Moral Theistic Argument: An Exercise in Ramified Natural Theology” (PhD diss., South African Theological Seminary, 2020).

[5] This paper will use the phrases “traditional view” and “traditional thought” as representing the view expressed in the paper’s opening sentence. As Samuel Brown has illustrated, there are a variety of ways Latter-day Saints may conceive of God from within this traditional viewpoint. See Samuel M. Brown, “Mormons Probably Aren’t Materialists,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 50, no. 3 (Fall 2017): 39–72.

[6] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 93.

[7] “Discourse, 5 February 1840: Historical introduction,” The Joseph Smith Papers.

[8] “Discourse, 5 February 1840.” See also, Ostler, Problems of Theism, 433.

[9] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1 [1 July 1843–30 April 1844],” 1970, The Joseph Smith Papers. See also, Ostler, Exploring Mormon Thought, 433.

[10] “Discourse, 5 February 1840.”

[11] “Discourse, 5 February 1840.”

[12] “Discourse, 5 February 1840.”

[13] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1,” 1968.

[14] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1,” 1970.

[15] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 435.

[16] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 438.

[17] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 438, emphasis in the original.

[18] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church History Topics, “Lectures on Theology (“Lectures on Faith”). Robert Millet calls the Lectures on Faith a “systematic study of faith.” See, Robert L. Millet, Precept Upon Precept: Joseph Smith and the Restoration of Doctrine (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016), 217.

[20] “Lectures on Theology.” See also Charles R. Harrell, “This Is My Doctrine”: The Development of Mormon Theology (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 121. Harrell claims that the consensus concerning authorship of the Lectures on Faith is that Joseph Smith “ultimately endorsed their contents and sanctioned their publication.” Joseph Fielding Smith reminds the reader that the Lectures “were not taken out of the Doctrine and Covenants because they contained false doctrine,” and that “the Prophet himself revised and prepared these Lectures on Faith for publication; and they were studied in the School of the Prophets.” See Joseph Fielding Smith, Seek Ye Earnestly (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1970), 194.

[21] Millet, Precept Upon Precept, 236.

[22] Joseph Smith Jr., Lectures on Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1985), 60.

[23] Smith, Lectures on Faith, 75.

[24] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 91.

[25] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1,” 1971.

[26] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 440.

[27] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 440.

[28] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 440.

[29] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1,” 1969.

[30] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1,” 1969.

[31] Joseph Smith Jr., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd rev. ed., edited by B. H. Roberts (Deseret Book: Salt Lake City, 1980), 6:305. See also Ostler, Exploring Mormon Thought, 441.

[32] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 441.

[33] “Accounts of the ‘King Follett Sermon,’” The Joseph Smith Papers.

[34] “Accounts of the ‘King Follett Sermon.’”

[35] “Discourse, 7 April 1844, as Reported by William Clayton,” 13, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[36] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Provo: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University), 361.

[37] “Discourse, 7 April 1844, as Reported by Thomas Bullock,” 16, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[38] “Discourse, 7 April 1844, as Reported by Thomas Bullock.”

[39] “Discourse, 7 April 1844, as Reported by Thomas Bullock.”

[40] Kevin L. Barney, “Joseph Smith’s Emendation of Hebrew Genesis 1:1.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 30, no. 4 (Winter 1997): 107.

[41] “Discourse, 7 April 1844, as Reported by Times and Seasons,” 614, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[42] Stan Larson’s amalgamated text of the King Follett Sermon is in harmony with the traditional published version of the discourse. It reads, “For we have imagined that God was God from the beginning of all eternity. I will refute that idea and take away the veil so you may see.” Larson’s modern amalgamation preserves Smith refuting the idea that God was God from the beginning. See Stan Larson, “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text,” BYU Studies Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1978): 201. See also B. H. Roberts, The Mormon Doctrine of Deity (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1903), 227.

[43] “History, 1838–1856, volume E-1,” 1972.

[44] Zucker L. “Joseph Smith as a Student of Hebrew.” Dialogue 3 (Summer 1968): 53.

[45] Barney, “Joseph Smith’s Emendation,” 128.

[46] Ostler, Exploring Mormon Thought, 442.

[47] Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 378.

[48] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 442.

[49] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 444.

[50] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 444, emphasis in the original.

[51] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 445.

[52] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 445.

[53] Ostler, Problems of Theism, 445.

[54] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by George Laub,” 30, The Joseph Smith Papers, emphasis added.

[55] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by George Laub,” 31.

[56] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by William McIntire,” 21, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[57] Blake T. Ostler, Exploring Mormon Thought: Of God and Gods (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2008), 20. See also Ostler, Problems of Theism, 443.

[58] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by Thomas Bullock,” 2, The Joseph Smith Papers.

[59] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by Thomas Bullock,” 3.

[60] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by Thomas Bullock,” 3.

[61] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by William McIntire,” 21.

[62] “Discourse, 16 June 1844–A, as Reported by William McIntire,” 21.

[post_title] => Was Joseph Smith a Monarchotheist? An Engagement with Blake Ostler’s Theological Position on the Nature of God [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 55.2 (Spring 2022): 37–72Joseph Smith’s teachings on God found in his preaching at the April 7, 1844 general conference, known as the King Follett Sermon, and Smith’s Sermon in the Grove, given at a meeting held just east of the Nauvoo Temple on June 16, 1844, have appeared to many to give strong support to this view. There, he taught that God was not always God but developed into God over time. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => was-joseph-smith-a-monarchotheist-an-engagement-with-blake-ostlers-theological-position-on-the-nature-of-god [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2024-01-28 18:43:47 [post_modified_gmt] => 2024-01-28 18:43:47 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://dj.slanginteractive.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=30130 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Praise to the Man: The Development of Joseph Smith Deification in Woolleyite Mormonism, 1929–1977

Cristina Rosetti

Dialogue 54.3 (Fall 2021): 41–65

However, the 1886 Revelation and subsequent statement also raised their own doctrinal questions that were continually developed through the lineage that became Woolleyite Mormonism. Namely, why was the resurrected Joseph Smith present alongside Jesus Christ at the meeting with John Taylor?

“My testimony is that Joseph Smith is at the head of this dispensation; he is a member of the Godhead and he is the One Mighty and Strong. And it is his work to set the house of God in order.”

Saint Joseph W. Musser, June 25, 1944

The Lorin C. Woolley Statement

On September 22, 1929, Lorin C. Woolley stood before a group of Mormon men and read a statement on the continuation of plural marriage. His statement began with an overview of June 1886, when leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints gathered to raise their concerns about the government confiscating Church property over the issue of polygamy.[1] According to Woolley’s account, many of the men were in support of appeasing the government to preserve Church assets. Leading the charge of this position was George Q. Cannon who, along with Hiram B. Clawson, Franklin S. Richards, John T. Caine, and James Black, met with President John Taylor for his consideration. On September 26, 1886, unable to come to a consensus among the men, Cannon suggested that President Taylor take the matter to God.[2]

In Woolley’s recollection of the evening, he sat in his room and began reading the Doctrine and Covenants, a compilation of LDS Church presidents’ revelations, when, “I was suddenly attracted to a light appearing under the door leading to President Taylor’s room, and was at once startled to hear the voices of men talking there. There were three distinct voices.”[3] Concerned for Taylor’s well-being, who was in hiding for his own participation in plural marriage, Woolley ran to the door and found it bolted. Perplexed, he stood by the door until morning, when Taylor emerged from the room with a “brightness of his personage.”[4] Looking to Woolley, and the other men now gathered at the door, Taylor explained, “Brethren, I have had a very pleasant conversation all night with Brother Joseph [Smith].”[5] Even more perplexed, Woolley questioned the voices, only to learn that the third voice was Jesus Christ. With little additional explanation, Woolley recalled Taylor placing “each person under covenant that he or she would defend the principle of Celestial or Plural Marriage, and that they would consecrate their lives, liberty and property to this end, and that they personally would sustain and uphold the principle.”[6] Following the alleged ordination, Taylor penned the revelation, popularly referred to as the 1886 Revelation, that affirmed the continued practice of polygamy and its place as an irrevocable doctrine for Latter-day Saints.

The 1886 Revelation was a watershed moment for the development of Mormon fundamentalism. In light of government prosecution and internal persecution of polygamists within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the revelation became a touchstone that affirmed the fundamentalist position on plural marriage. At the same time, the revelation became a marker of an alternate priesthood lineage outside of the LDS Church. Rather than follow the leadership of Wilford Woodruff and the subsequent end of polygamy, a priesthood led by John W. Woolley was initiated to preserve the practice. However, the 1886 Revelation and subsequent statement also raised their own doctrinal questions that were continually developed through the lineage that became Woolleyite Mormonism. Namely, why was the resurrected Joseph Smith present alongside Jesus Christ at the meeting with John Taylor?

Since Smith’s death in 1844, Mormonism struggled to place the martyr within their cosmology. In life, Smith’s role as the prophet of the last dispensation went largely uncontested among his followers. While this remains the case, his position in death is much more complex. In Christopher J. Blythe’s work on the apotheosis of Joseph Smith and the struggle to make sense of the late prophet’s identity after death, he describes how early Latter-day Saints conceptualized their late leader, including the use of past sermons that alluded to Smith’s identity as “veiled in mystery.”[7] The most notable and often cited of these mysterious remarks stated, “Would to God, brethren, I could tell you who I am! Would to God I could tell you what I know! But you would call it blasphemy and want to take my life.”[8] Smith’s vague statement on his identity shortly before his death left a knowledge void among his believers that allowed for diverse doctrinal speculation. Summarizing the various responses to Smith’s death, Blythe shows a range of positions, from beliefs that Smith belonged within the angelic hierarchy to assertions that his place was among the godsfrom assertions that Smith belonged within the angelic hierarchy to his place among the gods.

Through doctrinal routinization, LDS leaders sought to distance themselves from the latter position and clarify Smith’s place within Mormon cosmology. Within the LDS Church, Smith was doctrinally concretized as a mortal prophet who spoke with God, but was not God. However, as the LDS Church increasingly moved away from deification, with the eventual concretization of Smith’s place as the prophet of God, but not God, Mormon fundamentalists developed a doctrine of deity that named Smith as the third member of the Godhead. Most notably, Lorin C. Woolley and the men who descend from his priesthood lineage constructed a discourse on the nature of God that placed Smith back within Woolley’s own speculative framework on exaltation.

This article analyzes deification as a discursive practice that, together with Mormon theology of embodiment, exalted Smith to deity. Within many of the largest Mormon fundamentalist groups, Smith’s position as a member of the Godhead fills the void of Smith’s claim and answers for his continued presence in the lives of the Saints. For many Mormons gathering outside of the institutional LDS Church, Smith remains present in the lives of believers and continues to serve as a source of authority for minority Mormon groups because he became one of the gods.

Mingling with Gods

Following the death of Joseph Smith, a poem turned hymn appeared in the August 1844 issue of Times and Seasons, an LDS newspaper that circulated in Nauvoo, Illinois. William W. Phelps wrote “Praise to the Man” to celebrate the life and legacy of the late prophet. While the hymn underwent its own controversy and revision in the twentieth century, the chorus remained an iconic segment of the commemorative poem:

Hail to the Prophet, ascended to heaven! Traitors and tyrants now fight him in vain. Mingling with Gods, he can plan for his brethren; Death cannot conquer the hero again.

The writings of Phelps, and other early leaders within the Church after Smith’s martyrdom, constructed and concretized norms surrounding both faith and the language that serves as its foundation. Through writing, sermonizing, and doctrinal speculation, they created doctrines that became lived realities that governed the lives of the Saints. As authors recalled and theorized Smith’s existence, Smith’s existence came to life. In ensuing decades, Smith became an authoritative figure who governed those who believed themselves the heirs of the faith he founded.

When Lorin C. Woolley first speculated on the nature of Joseph Smith in 1932, he began with the language of Phelps’s hymn to articulate Smith’s central role in both the Church and the eschaton. The first recorded reference to Joseph Smith by Woolley occurred during a meeting of his School of the Prophets on March 6, 1932. Because Woolley did not keep a diary or a record of his revelations and doctrinal developments, early Woolleyite Mormonism is best known through the writings of the men in his Priesthood Council, the group of men ordained by Woolley to maintain the principles of Mormonism outside the bounds of the institutional Church.[9] Woolleyite doctrine recorded in Joseph W. Musser’s Book of Remembrances and the meeting minutes for the School of the Prophets give the most comprehensive overview of Woolley’s teachings.[10]

In his first lecture pertaining to Smith, Woolley expounded on Smith’s infamous “Would to God” statement. He explained:

J.S. repeated the statement—“‘Would to God I could tell you who I am.’ The saints are not yet prepared to know their Prophet leader.” Joseph S. is probably a literal descendent of Jesus Christ of Jewish and Ephraim lineage, the blood of Judah probably predominating—the ruling power. . . . Adam at head of Adamic dispensation; Christ at head of dispensation of the Meridian of Times and Joseph at the head of the last dispensation. “Would to God I could tell you who I am!” Being a God, he is mingling with Gods and planning for his brethren.[11]

In the last year of his life, Smith welcomed his followers to consider their eternality and the transformative aspects of death. In the often-cited King Follet Sermon, delivered by Smith in 1844, Smith remarked, “You have got to learn how to be a god yourself in order to save yourself.”[12] By articulating Smith as “mingling with gods,” Woolley postulated of an already exalted Smith, placing Smith within his own theological development and asserting that through his own mortal probation Smith was exalted into the realm of the gods.

Woolley maintained Smith’s unquestionable role as the prophet who restored the Church and revived the priesthood, or power of God, to earth. Having accomplished this mortal work, Mormons place Smith as the head of the final dispensation, or period of divine time in which an authorized leader holds the priesthood and ministers on behalf of God. As Woolley looked back on the leaders of various dispensations, he accounted for their potential exaltation, especially when viewed through the theological teachings of Brigham Young and the Adam–God doctrine.[13] The three dispensation periods most spoken about by Woolley were the Adamic dispensation that began humanity, the dispensation at the meridian of time led by Jesus, and the dispensation of the fullness of time led by Joseph Smith.[14] Placing these three individuals together, along with Smith’s own comments about his identity, afforded Woolley a starting point for positioning Smith not only within the realm of deity but within the Godhead of Mormon cosmology.

In the last years of his life, Smith offered several comments that alluded to his significance beyond an earthly leader of a temporal Church. The famous “Would to God” statement, paraphrased by Woolley, not only raised the question of Smith’s identity, but offered perceived sacrilege as the reason for not divulging, “But you would call it blasphemy and want to take my life.”[15] Smith’s vague comments were not a deterrent to Woolley. Rather, they were rich with meaning but in need of order and understanding. Central to the early fundamentalist worldview was the belief that doctrines are not available to all people. The assumption being that Smith could not reveal his identity to the members of the Church, but he potentially revealed it to the members of the priesthood.[16] In recollections of his time with Smith, Brigham Young, Smith’s successor as president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, noted that revelations are reserved for a certain time and often only to those prepared for them.[17] For Musser and other members of Mormon fundamentalist movements, the people best prepared for the weightier doctrines were the members of the priesthood. Whereas the Church tends toward introductory doctrine and casting aside of the more challenging principles, the priesthood is reserved to maintain the entirety of the faith, including the nature of God. Similar to Brigham Young’s comment, Woolley claimed that John Taylor, the third president of the LDS Church and the one claimed to have received the 1886 Revelation and ordained the earliest members of the Priesthood Council apart from the Church, eventually came to a knowledge of Smith as a god.

One of the great challenges to historians of Woolleyite Mormonism are his unsourced statements, such as Taylor’s realization of Smith as deity. Because Woolley did not make use of primary sources, Woolley’s own revelations became the primary source material for doctrinal formation. As a prophet, Woolley took disparate histories and statements and transformed them into concrete reality. His power as a leader was his ability to sermonize discourse into doctrine, transforming theological ideas into tenets of the faith. One of the greatest examples of this was Woolley’s brief accounts of the moments leading up to Smith’s martyrdom and the implication that Smith was aware of his divine status prior to death. At a May 5, 1932 meeting of the School of the Prophets, Woolley spoke on Smith’s preaching prior to his death, “Shortly before being murdered, Joseph Smith said: ‘I am going to take my place in the heavens,’ until which time John Taylor did not have a clear understanding of who J. S. was—one of the Gods.”[18] The understanding that Smith continued working on the other side of the veil was not a controversial idea in early Mormonism. In his public sermons, Brigham Young commented on Smith’s role in the afterlife and place in the final judgement, “Joseph Smith holds the keys of this last dispensation, and is now engaged behind the veil in the great work of the last days.”[19]

Because of Smith’s role as the head of this dispensation and subsequent martyrdom, Woolley’s sermons and doctrinal developments assumed his exaltation alongside the great patriarchs of the Old Testament, who were themselves believed to be heads of their respective dispensations. As these developments formed, Woolley’s sermons spoke Smith’s deification into existence. Drawing on Smith’s own theology of embodiment, Woolley preached about Smith as intermingling between the temporal and spiritual. However, it was not until the writings of Joseph W. Musser that Smith became identified with a particular deity of this world who consciously accepted a body. It was also under Musser that the doctrine was further concretized, to the detriment of all other speculative possibilities. Whereas Woolley made Smith a god in embryo, Musser transformed Smith into a god embodied.

The Office of the Holy Ghost

In 1934, Wooley passed away, leaving Joseph W. Musser one step closer to his future role as president of the Priesthood Council. Already before Woolley’s death, Musser’s authorship of multiple doctrinal pamphlets and editorial work for the monthly Truth magazine made him the primary conduit of Woolleyite doctrine.[20] In his leadership role, Musser inherited a religious community marked by both outside prosecution and internal persecution. Having been excommunicated from the LDS Church, Musser joined the Woolley Priesthood Council, an organization that he conceptualized as the highest Joseph W. Musser expression of Mormon priesthood and the avenue for preserving Joseph Smith’s most sacred doctrines.

While most of Musser’s theology focused on the centrality of the priesthood and the continuation of plural marriage, Musser also penned the first full-length fundamentalist pamphlet on the nature of God. Michael, Our Father and Our God: The Mormon Conception of Deity as Taught by Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, John Taylor and their Associates in the Priesthood first appeared in volume 3 of Truth magazine and was later reprinted in four editions as a stand-alone pamphlet. The pamphlet sold for 25 cents and purportedly circulated among LDS elders quorums and Sunday Schools throughout the intermountain West.[21] In this work, Musser articulated the necessity of embodiment for exaltation and acted as an ordering agent who clarified doctrine of God in a way that solidified its place in fundamentalist theology. Through his speculative discourses, Woolley brought doctrine to life. Through his widely circulated writing, Musser solidified Woolley’s speculations as truth.

During the April 7, 1844 conference of the Church, Joseph Smith stood before his congregation and emphatically stated, “We have imagined that God was God from all eternity. These are incomprehensible ideas to some, but they are the simple and first principles of the gospel, to know for a certainty the character of God.”[22] In line with Smith’s statement on the first principle, Musser’s pamphlet was an attempt at Mormon theology that both defended Young’s theory of divine embodiment and accounted for human exaltation. For Musser, the goal of the pamphlet was “acquainting the Saints with the true God of Israel, His genesis, His character and attributes.”[23] Michael, Our Father and Our God, in all of its editions, fulfilled Smith’s 1844 call for the Saints to know for certain the nature of God, a not-too-distant and embodied being that was both familiar and humanity’s goal.

Whereas Woolley made claims regarding the deification of Smith, and the other members of the Godhead, Musser sought to answer the mechanics of the claims. Michael, Our Father and Our God was foremost a critique of contemporary LDS leadership that disregarded Brigham Young’s teaching of the Adam–God doctrine. This doctrine had been central to early Utah Mormonism. On April 9, 1852, Brigham Young delivered an address in the tabernacle for the semiannual general conference on the nature of God. During his sermon, Young asserted that Michael entered an earthly body in Eden and became Adam, “the first of the human family.”[24] At the end of his life, having served his God faithfully, Adam was translated back into his celestial body and attained exaltation.[25] “As a man who was exalted and became God, Adam affords spiritual beings the opportunity to follow his mortal existence and seek embodiment for the purpose of becoming gods.