Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 3

The Secular Binary of Joseph Smith’s Translations

By 1828, Joseph Smith had carefully created copies and an “alphabet” of the characters on the gold plates to take to scholars to “git them translated.”[1] At this early stage it is easy to see him feeling around to understand his boundaries and to position himself to translate.[2] But what did it mean to translate in a secular world? According to Joseph, he sent the list of characters and a small sample of his own translation with his friend and benefactor Martin Harris to have them examined and academically translated.[3] In other words, Joseph almost immediately faced the problem of finding equivalent characters, symbols, and language to represent revelation from God. He ingenuously sent the characters and a piece of his own translation to linguists to identify a translation equivalency from the characters to English.[4]

By looking for someone to “git them translated,” Joseph opened himself up to an academic translation of the gold plates. In fact, the list of characters that he sent with Harris presented the possibility that he may have even obtained a one-to-one translation in an alphabetic format. One can only imagine Joseph Smith with a “reformed Egyptian” lexicon provided by Samuel Mitchell or Charles Anthon, sorting through the characters on the gold plates. Nonetheless, once Martin Harris returned without an academic translation of the characters, Joseph did not pursue a linguist translation or a one-to-one translation of the characters. He made a conscious decision to distance himself from a linguistic translation and accepted that the kind of translation he would produce was not done by finding equivalence between “reformed Egyptian” and English.[5] Joseph ignored all precision for equivalence in the translation by assuming that the words revealed to him constituted a translation of the characters. In other words, Joseph Smith was not in a position to know for himself whether the translation was correct; he had to trust that God was delivering the correct translation to him.

This episode highlights a central issue in the analysis of Joseph Smith’s translation projects and positions him squarely within the secular age. Were his translations based on a verifiable correspondence of symbols to English words, or did the process require a disconnected metaphysics that was incommensurable to the original symbols? The debate about Joseph Smith’s translations have primarily assumed that the translation was commensurable and focuses upon theories of authorial involvement of Joseph Smith. Scholars place their theories of translation on a spectrum in which God was completely responsible for the translation on one end and Joseph Smith was completely responsible on the other end. This is usually paralleled with another spectrum for how he translated, ranging from reading God’s translation from a seer stone to postmodern critiques about discourse.[6] With the intention of both contributing to and challenging these parallel spectrums of thought, this article will demonstrate Joseph’s realization of the incommensurability of his own translations by looking at his attempts to produce a linguistic translation. It does this by comparing three seemingly disparate translation projects that have rarely been associated together: the Book of Mormon “caractors” document (1829), the Pure Language Documents (1833/35), and the Kirtland Egyptian Alphabet (1835). Running through this examination, it will explore the tension between commensurability and incommensurability of translation.

This paper demonstrates continuity in Joseph Smith’s translation projects by tracking translation and commensurability between 1828 and 1835, giving special emphasis on “reformed Egyptian” characters and their possible English translation. These documents seem to be examples of a translation process that explicitly tried to assign a specific English meaning to a specific character from the mysterious languages from which Smith was translating. Yet, this paper challenges the theory that Joseph Smith was engaged in translation commensurability, i.e., the idea that there is a direct correspondence between two languages. Rather, this paper demonstrates that Smith’s translation projects, even in his most mechanical examples, relied on translation underdetermination, which refers both to the fact that his translations were not precise one-to-one linguistic translations and the broader idea that language offers multiple meanings and possible interpretations. It will illustrate Joseph’s failure to provide a commensurable translation of Egyptian characters and his own acceptance of an incommensurable translation.

Linguists have made it clear that perfect equivalency in translation is impossible, but philosophers of science go even further to demonstrate that our evidence at any given point is underdetermined, or insufficient in determining what beliefs we should hold about nature. Provoking the demise of twentieth-century logical positivism, Willard Van Orman Quine’s theory of the indeterminacy of translation argued that there could be multiple, equally correct translations of one word.[7] Reflecting the problem of translating, Quine skeptically challenged whether identifying synonyms was possible, questioning even whether an idea in one’s head was not a theoretical translation in the first place that needed justification, not just symbolic representation. Even native speakers misunderstand given the complex association with the language and various depths of expression and cultural meaning.[8] Joseph Smith expressed his own sense of underdetermination in his translations, as well as in his revelations. Such a close study of what he thought he was doing can reshape the current debates about his translations by focusing on the role that revelation and religious experience played in them.

This article will examine the tension present within Joseph Smith’s translations between the acceptance of an incommensurable translation and his attempts to find a commensurable translation. This binary is explored in juxtaposition with religion and secularism. The tension illustrates competing pulls between “religious” experience as the mediator of truth and a “common sense” appeal to verifiable secular knowledge.[9] In antebellum America, the competition between religious and secular knowledge shaped the quest for “true religion.”[10] Historian John Modern argues that this secular impulse in the period “conditioned not only particular understandings of the religious but also the environment in which these understandings became matters of common sense.”[11] In this view, the question of a religious and a secular knowledge are not in opposition to one another, but so intimately bound together as to shape and define the contours of each. This tension was the “connective tissue” in Joseph Smith’s world that made true religion, as Modern describes it.[12] In fact the formation of this tension and the creation of this relationship convinced Joseph Smith and his followers that they were religious in a secular world.[13] Like the brilliant research of Tomoko Masuzawa in which she showed how secularism made religion universal, the incommensurability of translation made Joseph Smith’s translations legitimate, but only through that binary.

The Book of Mormon

Translation was a process of change, but in Joseph Smith’s experience that change was not demonstrably a process of equivalent change, like a one-to-one translation of words. In the case of the Book of Mormon, for example, even claiming that there was a commensurable change between languages fails to demonstrate how they would know that. David Whitmer was one of the few witnesses of the translation that tried to make Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon commensurable with the original characters. He apparently told a reporter that “the graven characters would appear in succession to the seer, and directly under the character, when viewed through the glasses, would be the translation in English.”[14] Even if David Whitmer’s story of the translation process were true, in which words and equivalent characters appeared on Joseph’s seer stones, he still could not experience commensurability without knowing “reformed Egyptian.” This leaves Smith within a scenario in which he could not personally compare the gold plates with the English translation of the Book of Mormon. He experienced the process but he did not know through personal experience that it was correct or whether its modern translation represented a historical ontology or a nineteenth-century ontology. He simply could not know.

As early as 1829, the text of the Book of Mormon is self-aware of its incommensurability in translation. It states: “But the Lord knoweth the things which we have written, and also that none other people knoweth our language; and because that none other people knoweth our language, therefore he hath prepared means for the interpretation thereof” (Mormon 9:34). Mormon is self-aware of the problem of translation, since he is worried about his own ability to translate the records into “reformed Egyptian” and he is especially cognizant of the problem of future peoples being able to translate his translations and abridgements. Even reading words from a seer stone, if this is considered a petri dish for perfect transmission, still has the transformation required of the reader, not to mention the reality of errors of human cognition and inevitable reassessment of the canonical text. Just think of the issue of ontological assumptions being made by the producer of the text and the ontological assumptions being made by the reader, especially if they are separated by thousands of years and culturally at odds with each other.[15] The complexity of identity and cognition that come before speech inevitably problematize the outcome of Joseph Smith reading words from a seer stone, let alone translating cultural and ontologically oriented ideas.

The “caractors” document illustrates the point. Though there was a clear disconnect between the characters on the gold plates and the text in the Book of Mormon, Joseph still valued the copies of the characters that remained. Just because he could not assess the commensurability of the translation did not necessarily mean that he did not think it was commensurable. The interest in this kind of evidence for his translation and its relationship with the incommensurability of his translations eventually created a chain of interest in ancient characters from the Book of Mormon “Egyptian” to the book of Abraham “Egyptian.” There are several documented examples from 1828 to 1835 of Joseph identifying this tension. Below we will examine the examples of Joseph Smith attempting to translate Egyptian characters. In fact, even the Pure Language Documents are eventually connected with Joseph Smith’s most concerted efforts to verify or connect his translations back to an ancient language, or at least ancient characters.

Early Revelations

The secular tension present in Smith’s translations is also present in experiences within the leadership too. An important example is found in his history, in which Joseph noted that in November 1831, when they were compiling the early revelations that would eventually be a part of the Doctrine and Covenants, they had “some conversation . . . concerning revelations and language.”[16] Joseph’s revelation at the conference declared that through the spirit and a kind of communion with God, he produced the revelations, in which God declared that his servants were given this revelation “in their weakness after the manner of their language.”[17] Admitting the gap between religious experience and what his servants declared created space for others to experience the divine and to know that Joseph Smith’s revelations were from God. This was similar to the idea that the text led back to enthusiastic experience. The text of the revelation was connected to an experience of the divine. Joseph’s revelation promised:

I say unto you that it is your privilege & a promise I give unto you that have been ordained unto the ministry that in as much as ye strip yourselves from Jealesies & fears & humble yourselves before me for ye are not sufficiently humble the veil shall not be wrent & you shall see me & know that I am not with the carnal neither natural but with the spiritual for no man hath seen God at any time in the flesh but by the Spirit of God neither can any natural man abide the presence of God neither after the carnal mind ye are not to able to abide the presence of God now neither the ministering of Angels wherefore continue in patience untill ye are perfected let not your minds turn back & when ye are worthy in mine own due time ye shall see & know that which was confirmed <upon you> by the hands of my Ser[v]ant Joseph.[18]

Accepting the fact that his language was flawed, Joseph was asking the elders at the conference to have this experience and testify that his revelations were from God, in spite of his inability to communicate as clearly as God.

Some of the elders questioned the verity of Joseph’s revelations because of his linguistic expressions. Joseph challenged them to write a revelation themselves that would be as efficacious as the revelations that he had produced. William E. McLellin, who was the primary instigator, attempted to “write a commandment like unto one of the least of the Lord’s, but failed.” All of the elders apparently watched eagerly as McLellin made a “vain attempt of man to imitate the language of Jesus Christ.” This spectacle demonstrates the secular binaries (foundationally emerging from the binary of religion and secularism) shaping early Mormonism, never letting the divine voice stand without its companion, the secular language of humankind.[19] Writing about his prophetic role to produce revelation, Joseph wrote that “it was an awful responsibility to write in the name of the Lord.”[20]

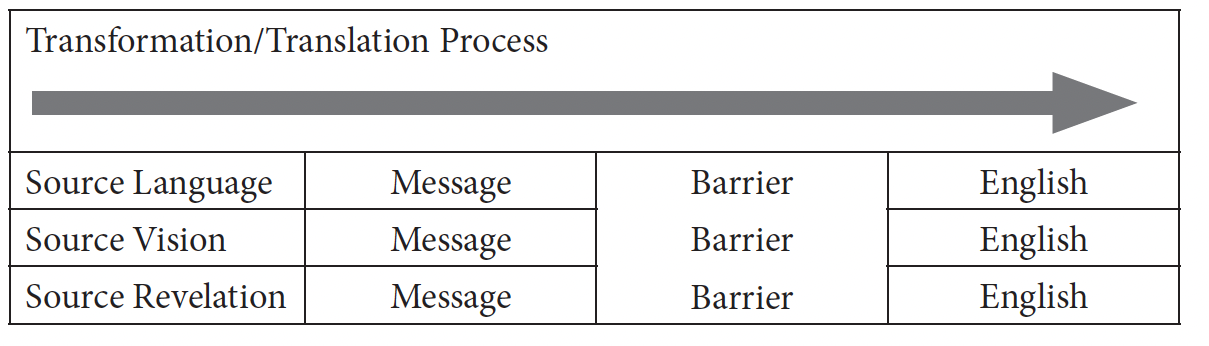

Chart 1: Transformation/Translation Process

This builds a bridge between his translations and his revelations that we will need cross back and forth on, while focusing on translation. Before turning to another example, it’s worth noting that translation can extend beyond just intra-language translation, such as the translation between religious experience and language. George Steiner explains that “translation is one in which a message from a source-language passes into a receptor language via a transformational process,” but his point lies within the fact that “the same model . . . is operative within a single language.”[21] (See Chart 1.) On one level, Joseph Smith was translating time in one language, describing the past and even prophesying the future, all in English. But on another level of translation, he was operating within one language, translating his experience. Because his translations did not include a personal transformation between two languages, it is difficult to completely untangle his translations from his revelations. As the next example will show, they were not historically separate either.

McLellin’s challenge was neither the first time nor the last time Joseph Smith faced the problem of the indeterminacy of language with his colleagues. This all became more of a reality when he and Sidney Rigdon faced the problem of describing their vision (D&C 76) in early 1832. They eventually declared:

But great and marvelous are the works of the Lord, and the mysteries of his kingdom which he showed unto us, which surpass all understanding in glory, and in might, and in dominion; Which he commanded us we should not write while we were yet in the Spirit, and are not lawful for man to utter; Neither is man capable to make them known, for they are only to be seen and understood by the power of the Holy Spirit, which God bestows on those who love him, and purify themselves before him; To whom he grants this privilege of seeing and knowing for themselves. That through the power and manifestation of the Spirit, while in the flesh, they may be able to bear his presence in the world of glory. (D&C 76:114–18)

The Spirit was necessary to mediate the communication precisely because of the difficulty that language itself posed.

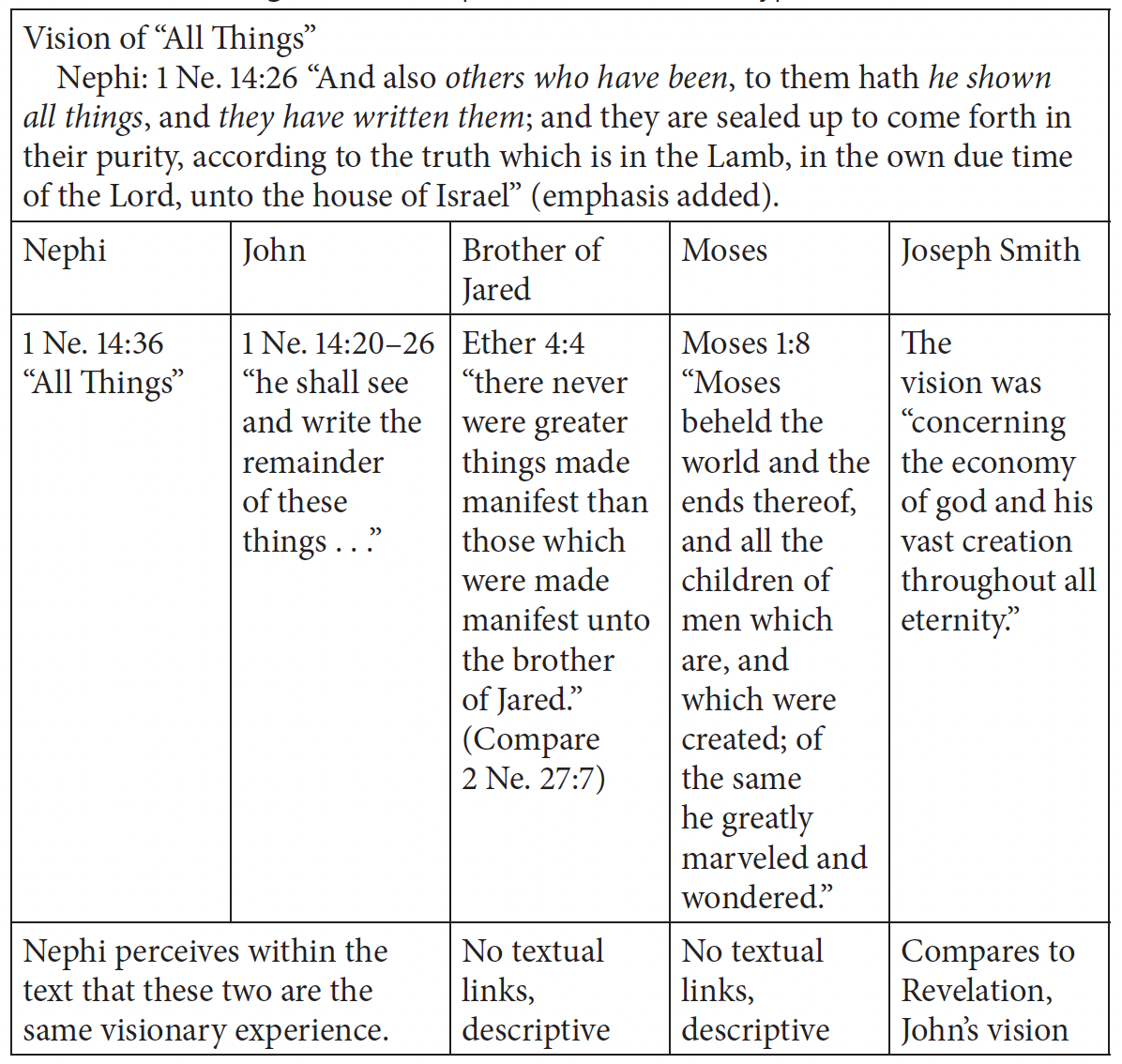

Apparently, visions were particularly difficult to translate into effective words. Yet, Joseph had produced examples of how past prophets had described their visions in some of his other revelations and translations. In fact, the Book of Mormon includes examples of visions similar to Joseph Smith’s vision.[22] (See Chart 2.) Nephi explains that John’s vision in the New Testament (Revelation) was also a vision like unto his own (“all-seeing,” panoptic, or panoramic vision). The Book of Mormon explained that both Nephi and John had “seen all things” in vision, and Nephi compared what John would write to know what he should write down about his vision.[23] They both had visions and both stayed true to their perspective of their visions.

Nephi’s perception of a shared experience with John made their experiences comparable, but their individual perspectives also mattered and determined how they wrote about the vision. Like Nephi, Joseph Smith also compared his vision (D&C 76) with John’s vision.[24] Having described a kind archetypical (panoptic) vision in the Book of Mormon and now having experienced his own vision, he turned to these other authors/prophets (such as John) to know how to write about his incommensurable vision. When he finally writes D&C 76, he explains that God commanded him and Rigdon to write the revelation, but he worries that he will not be able to communicate what he saw in writing. Eventually, he explains in D&C 76 that “Neither is man capable to make them [the experiences in the vision] known.” Language was his problem, not transcendence or knowledge, demonstrating the overarching tension of the secular binary.[25]

Chart 2: All Seeing Vision Comparison as an Archetype

Joseph’s comparison demonstrates his acceptance of the incommensurability of language. Nephi claimed that John had the same vision, and then Joseph used John’s description of his vision (Revelation) to undergird his own interpretation and perspective about his vision. Having examined the text of Revelation carefully, Joseph asked questions about the text, then God would reveal the answer with the meaning and interpretation (D&C 77). His revelation (D&C 77) about John’s vision was written down just after he had seen his own vision. This revelation suggests that he recognized his inability to write about his vision, but it also suggests that his perspective mattered. D&C 77 is an example of how he could clearly address these visionary experiences in his own context and interpretation, after accepting the incommensurability of language.[26]

This overlap between translation and revelation became even more distinct within this project to translate his vision. In fact, his experience receiving D&C 77 led Joseph to ask additional questions about John’s vision. Instead of looking for a word for translation or an acceptable interpretation, he wanted to ask ontological questions about the nature of God. In the same format as D&C 77 (a series of questions posed from the text of Revelation followed by their respective answers), he asked God what the name of God was, provoked from the text of Revelation (3:12). The title of the revelation that he received read “First Question What is the name of God as taught in the pure Language.” This was unlike D&C 77 in the fact that it was not asking for an interpretation. It was asking for a translation in “the pure language,” or in a language that was not incommensurable. That meant that God’s name could not be delivered to him in English, or Egyptian, or Hebrew. Translation into these languages would all be incommensurable, but he seemed to be asking for something more than that. He seemed to be asking for something even more than the primordial language of Adam. He was asking to eliminate the religion and secularism binary to just have religion, which would prove to be difficult, securing him in a kind of prison.

Pure Language Document(s)

Joseph Smith was aware of the problem of translatability since his own translations contemplated a time when there was no need for translation. The book of Moses, which was written within the first year after he established the Church of Christ, expressed similar concerns with the incommensurability of translation. It establishes a timeframe in the beginning of the world when there was only one language, while also claiming that it was “a language which was pure and undefiled” or the language of Adam (Moses 6:5–6). This represents a moment of pure communication, while still finding itself under the strong arm of ontological relativity and the realization that there is still a kind of translation in the movement from prelinguistic cognition and linguistic expressions. Then the book of Moses introduces the reality of translatability within its own pages by describing Enoch trying to preserve Adam’s language amid the multiplication of languages. Even though ontological relativity played a role from the beginning of this narrative, translatability is a central concern, even a central epistemology, for Joseph Smith’s scripture at the earliest stages of his ministry and reemerging in the spring of 1832.

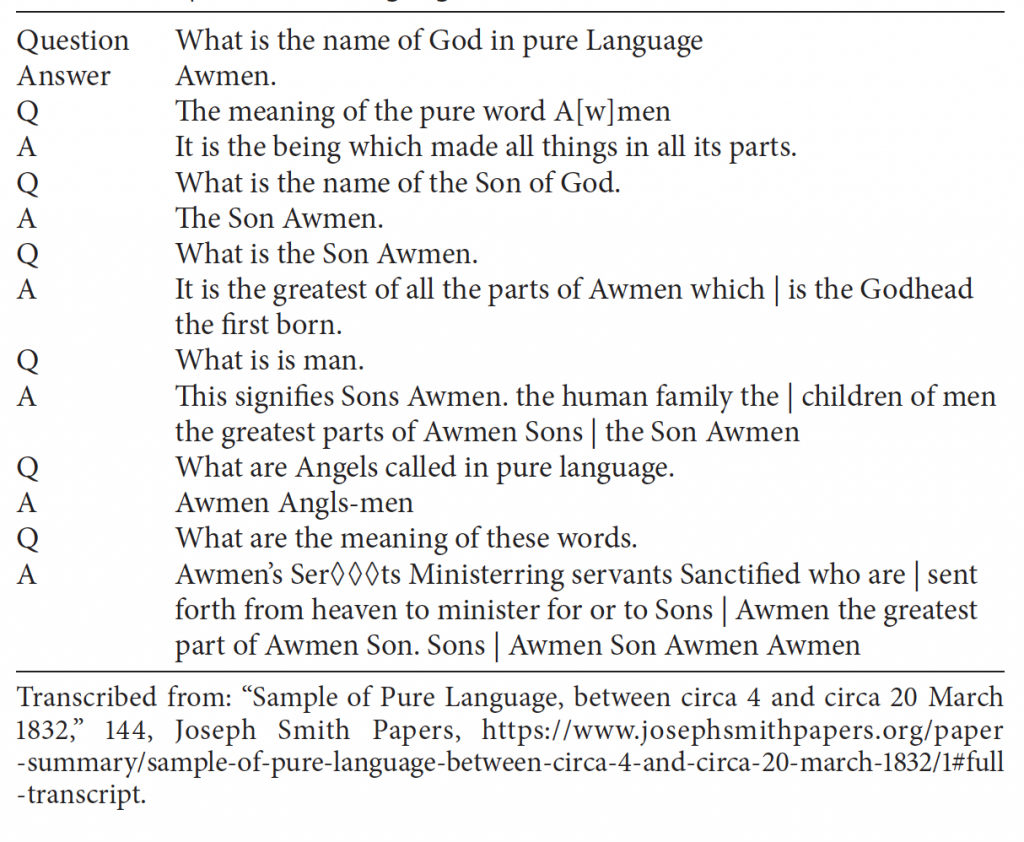

The “Sample of Pure Language” was not just evidence of Joseph Smith’s musings about translation—it represented an important element in his epistemology. First of all, it emerged within the context of creating a framework to transform Joseph Smith’s panoptic vision (D&C 76) into English. Second, it imagined the possibility of a prelinguistic linguistics, in which there was a time when there was a single “pure language.” Scholars have generally associated the “pure language” with the language of Adam, or the “undefiled” language described in Moses 6:5–6, or as the Joseph Smith Papers has associated it with the Jaredites and the confounding of languages.[27] (See Chart 3.) Nonetheless, the “pure language” could have just as easily represented a language before Adam’s language, which was the first corrupted language. Finally, this document is revelation about translation. Though it was not published in the 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, it was included within the manuscript version of Smith’s revelations. Even over time, it was not forgotten though it was not broadly available. Orson Pratt preached about the revelation in 1855, explaining that “there is one revelation that this people are not generally acquainted with . . . it has never been published, but probably will be in the Church History.”[28] This revelation demonstrates the dilemma of receiving “pure” communication and the inevitable incommensurability of translation. What Joseph was doing here has been debated for decades and few have agreed upon its purpose.

One thing that is clear is that this revelation marks Joseph Smith’s cognizance of the incommensurability of language, which reveals the secular binary. The idea of it being a “sample” suggests that the content itself was not its only purpose. Answering the question of what God’s name is was clearly important, but this document suggests that it is a sample of an overarching question that was being asked. The question of language and its nature was a central feature of this document. Joseph was not only interested in theological answers; he was interested in epistemology and communication. He chased these ideas throughout his ministry until he died. The very idea of evoking an original language that was “pure” is an explicit acceptance of the incommensurability of language and translation. Change, or translation, was not a real possibility. Returning to the original language was the most effective way to access the pure knowledge that he sought. Yet, even in this document, the answer is still in English.

Chart 3: Sample of Pure Language

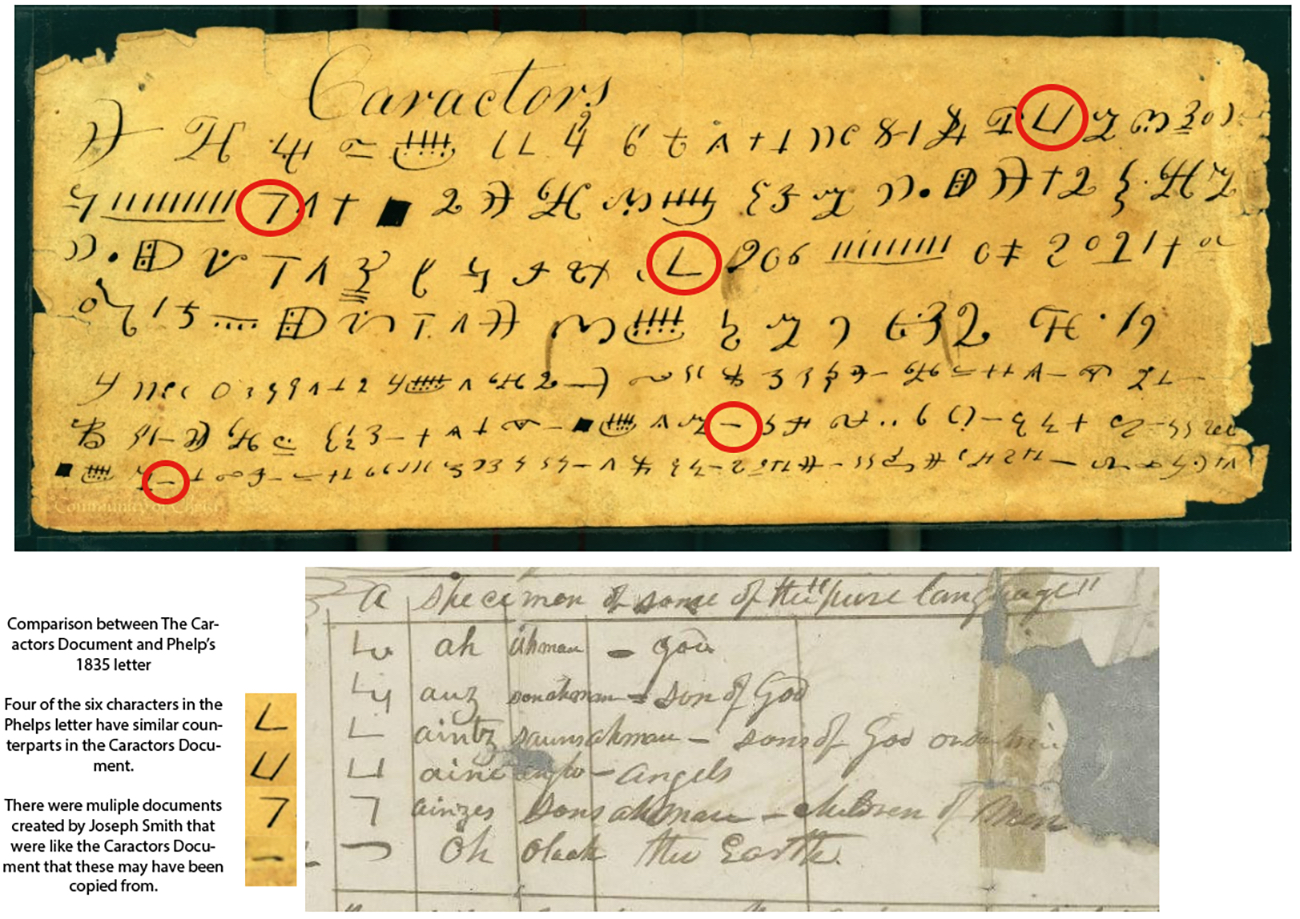

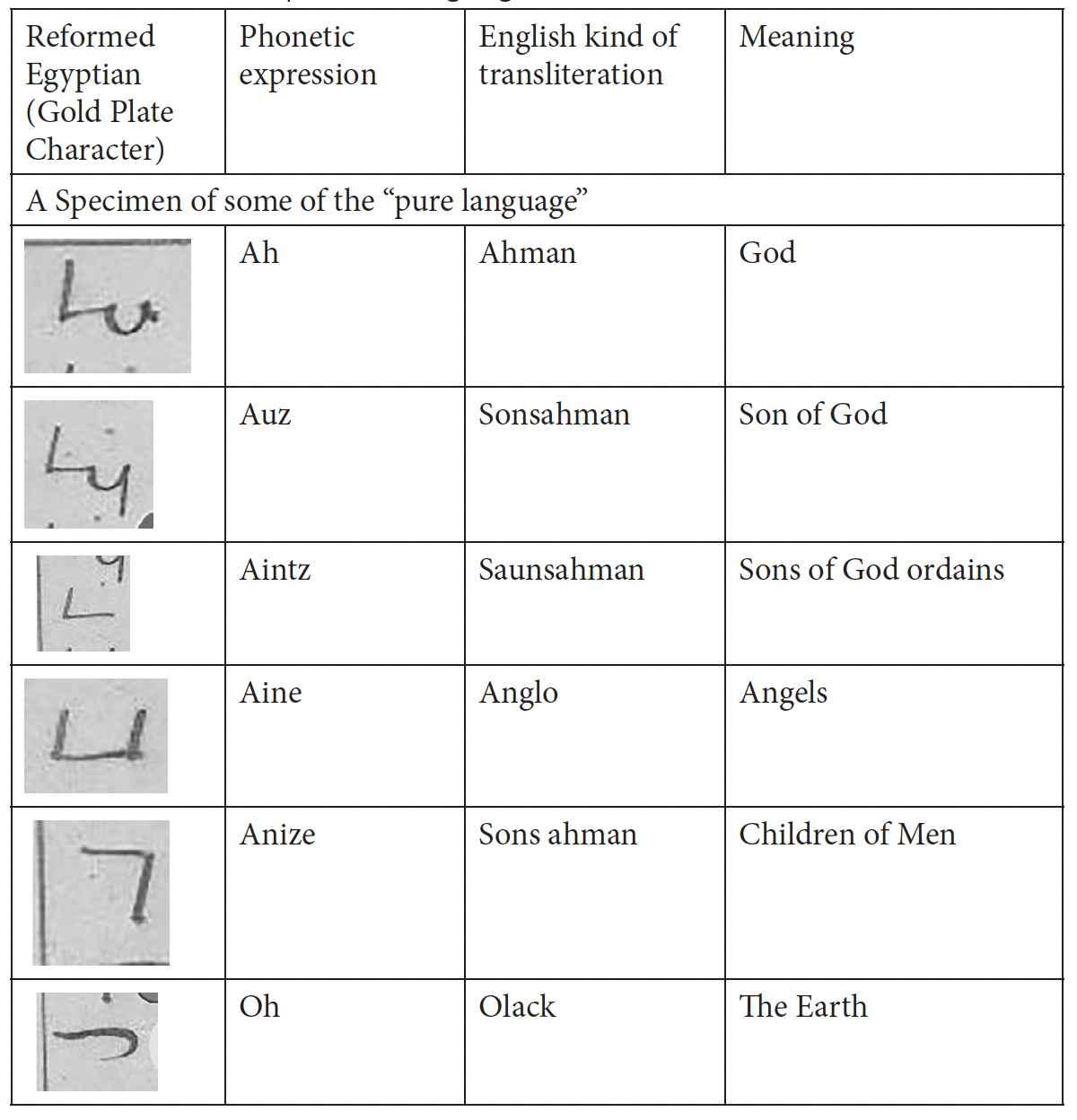

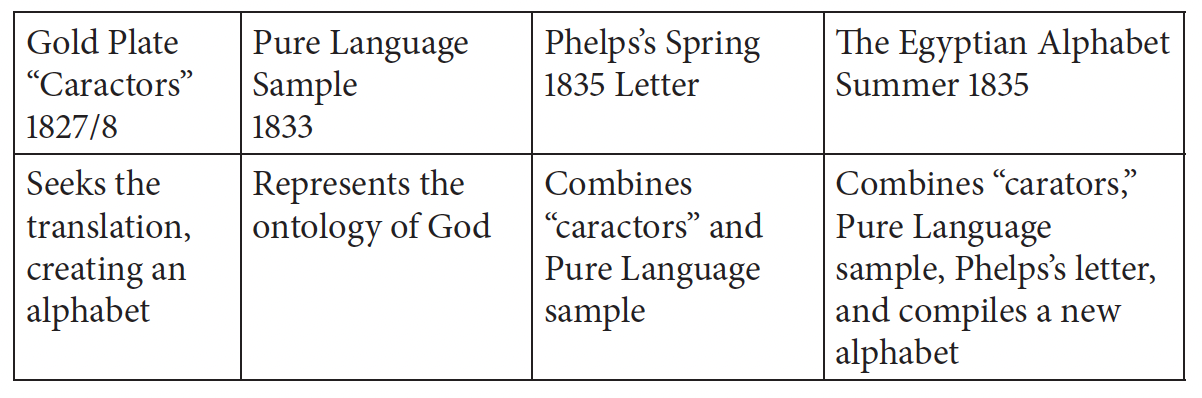

Joseph never forgets the fact that what has been revealed to him still has to be delivered in English and he keeps exploring this idea through the Pure Language Document. This is demonstrated through a few copies of the document. Perhaps the most telling and interesting version of the document was written in the spring of 1835 as part of a letter written by W. W. Phelps to his wife. His letter included a copy of the Pure Language Document, but combined it with characters that Joseph had produced as examples of the characters on the gold plates. Phelps borrowed six characters from the Book of Mormon characters documents and lined them up with the six expressions made in the Pure Language Document (see Comparison #1). Lined up next to the characters are six phonetic sounds, followed by a row of English/pseudo-Hebrew transliteration terms taken primarily from the Pure Language Document. Finally, Phelps aligned the six rows with what seems to be the meaning (also drawn from the Pure Language Document) of the six characters.[29] (See Chart 4.)

This is a comparison between The Caractors Document and Phelps’s 1835 letter. Four of the six characters in the Phelps letter have similar counterparts in the Caractors Document. There are multiple documents created by Joseph Smith that were like the Caractors Document that these may have been copied from.

Chart 4: W. W. Phelps Pure Language Chart, 1835

Phelps’s letter appears to be a one-to-one translation of six characters from the gold plates. His letter is the first known document to express commensurability between the characters and an English expression of the characters. Before Phelps’s chart, there was nothing. Even more remarkable is the fact that Phelps used the Book of Mormon characters, but instead of identifying a word or phrase from the Book of Mormon, he associated their meaning with the revelation that was provided in the Pure Language Document.

However, there is no extant document trying to connect the translation of the “caractors” with any specific passage in the Book of Mormon. The concepts of God, son of God, humankind, and angels are used in the Book of Mormon but never the term “ahman,” nor is the ontology expressed in the Pure Language Document found within its pages. Nonetheless, “ahman” becomes an important concept in the Doctrine and Covenants, especially in its association with D&C 78 and “Adam-ondi-ahman,” a place where Christ would return as part of the Second Coming.[30] This is strange, but it does demonstrate their efforts to identify commensurability between characters and revealed text.

There is another document that also tries to identify commensurability in a similar way. Oliver Cowdery made some notes that also point toward a kind of one-to-one translation of the characters from the Book of Mormon. Having edited this document for the Joseph Smith Papers, I can say it’s difficult to date its production with any accuracy and it was relegated to the appendix of Documents Volume 1. Nonetheless, the first part of his notes includes a verse from the book of Jacob labeled “English,” followed by an indecipherable phrase labeled “Hebrew.” Then the second part includes “Book of Mormon characters” presumably with their translation into English above (see “Written and Kept for Profit and Learning” below). Assuming this is produced at the same time, it demonstrates their efforts to make translation commensurable and binary.

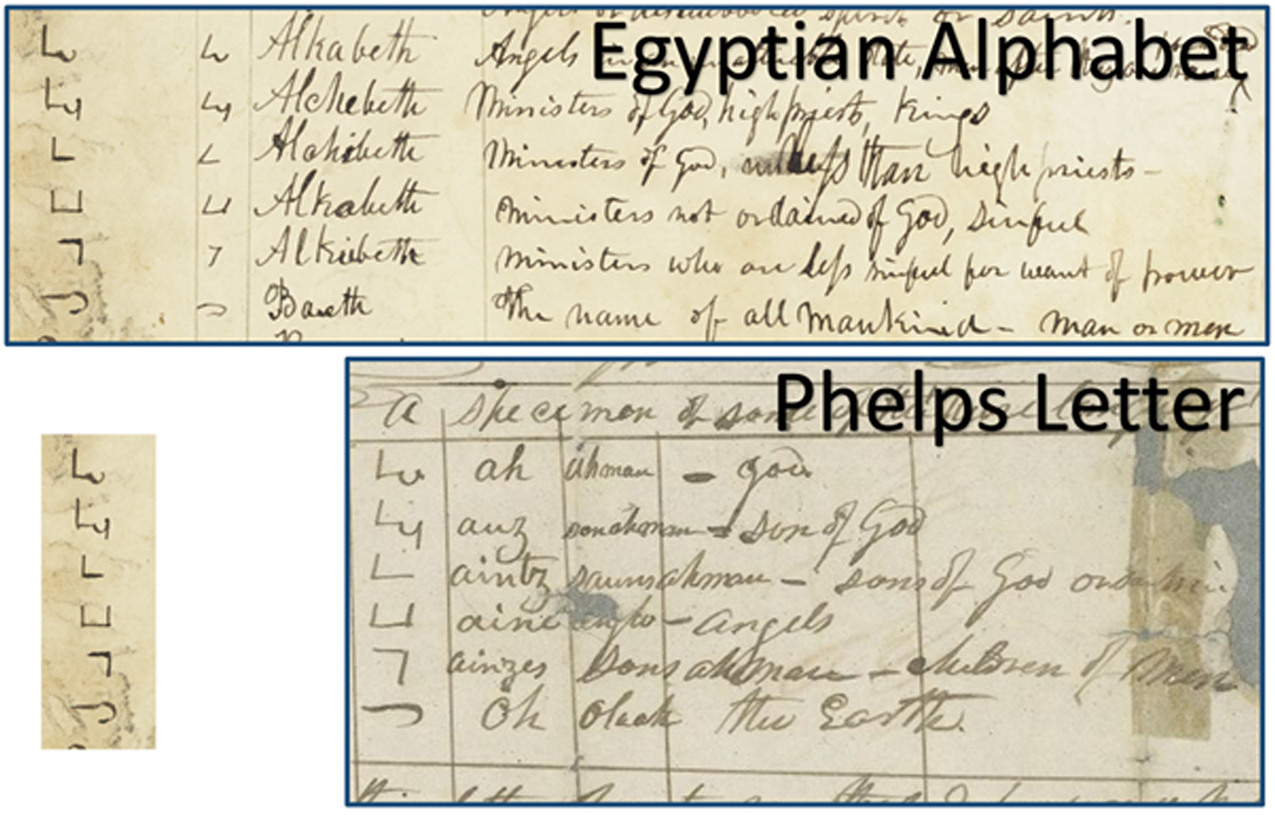

The Phelps letter includes six characters that were also included in the Egyptian Alphabet. This overlap demonstrates continuity and influence from the Pure Language Document (referenced in the Phelps letter) to the Egyptian Alphabet. The definitions represent a series of different sounds and meanings, but still provide an expansion of a root sound or definition (like “beth” or “ahman”) into five degrees of ministry.

What was happening here is unclear, but the Cowdery document demonstrates their efforts to develop a correspondence translation between the Book of Mormon and the “caractors.” However, they fall short in two distinct ways. First, they are not connected to any specific passage and indeed even represent ideas and terms that are not in the Book of Mormon at all (for example, the phrase “the interpreters of language”). Second, they still don’t know the original language in order to develop a corresponding translation (interestingly, within months they begin studying Hebrew). They rely on revelation to make their translations, but not on a verifiable translation process. Because of this, even the most mechanical and minor efforts to show a correspondence of any kind, whether tight or loose, between the English text of the Book of Mormon and the mysterious script of “reformed Egyptian” still do not provide any evidence of a correspondence theory of translation. But that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t create a binary tension.

The Kirtland Egyptian Alphabets

The Phelps letter led to further attempts to create a kind of correspondence translation of the Book of Mormon and the gold plate characters. In the summer of 1835, the three individuals most interested in this work on translation and the search for a pure language over the previous eight years took another try at it. The Egyptian “caractors” copied from the gold plates in 1828 and Pure Language Document that Joseph Smith began in early 1828 and in 1832 have always been considered separately from the first alphabet of Egyptian characters produced in the summer of 1835. Yet, this research shows that they started that summer by examining the Egyptian from the gold plates, not the papyri. This can be demonstrated through the “Egyptian Alphabet” documents that have been assumed to have come from the papyri. Oliver Cowdery, W. W. Phelps, and Joseph Smith each worked on three separate alphabet documents, though they were copies of each other with a few idiosyncratic changes, collectively known as the “Egyptian Alphabet”; it should be relabeled the “Combined Gold Plates Egyptian and Papyri Egyptian Alphabet,” though I will continue to call it the “Egyptian Alphabet.”

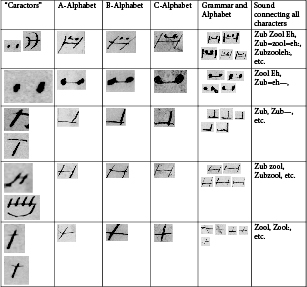

This proposed title change is important. These alphabets shared a similar format and organization with Phelps’s chart including Book of Mormon characters, phonetics, transliteration, and meanings.[31] Further connecting them, some characters from the Book of Mormon “caractors” document ended up in their alphabets just like they ended up in Phelps’s letter on pure language. Some of the Egyptian characters in the alphabet documents have exact matches to the characters associated with the gold plates in 1828 (to my knowledge, the list below is the first time this comparative list has been identified in print or otherwise). Curiously, Oliver Cowdery’s edition of the Egyptian Alphabet shows more signs of being associated with the earlier Book of Mormon characters project. Cowdery’s alphabet appears to be the original or first of the three alphabet documents. Not only do the characters match many of the extant samples of Book of Mormon characters, but Cowdery also frames his alphabet like John Whitmer did for the Book of Mormon “caractors” document by calling the symbols “characters,” while Phelps and Smith called them “Egyptian.” This seems to suggest a relationship between the 1828 alphabet “caractors” project and the 1835 Egyptian Alphabet project.[32] (See Chart 5.)

Chart 5: Comparing Documents Associated with Reformed Egyptian Characters

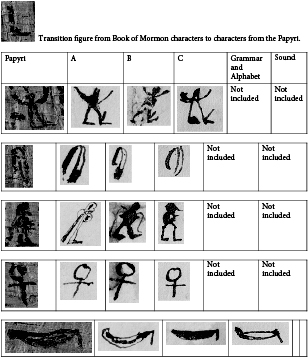

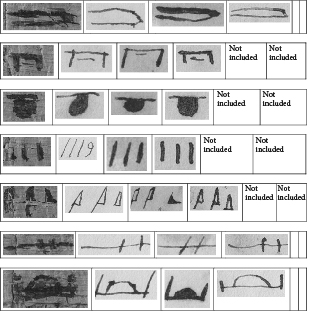

The project that had just begun that summer to develop an Egyptian alphabet experienced an unexpected boost when the Saints came into contact with some genuine Egyptian materials. In July 1835, Joseph Smith and some helpful financiers purchased several scrolls of Egyptian papyri. Since Joseph Smith had already translated the gold plates, which were in “reformed Egyptian,” the papyri became all the more intriguing and a great way to extend their study of language. After recently returning to studying the Book of Mormon’s “reformed Egyptian,” the arrival of the mummies and papyri in Kirtland must not have seemed like a coincidence. It’s clear that Cowdery, Phelps, and Joseph were not finished with the alphabet; once the papyri arrived, Joseph continued by adding characters from the papyri to the list of Book of Mormon Egyptian. The last page of all three copies of the alphabet show the explicit shift from gold plates characters to characters taken from the newly purchased papyri. Though they stopped abruptly after including only a handful of characters from the papyri, the unfinished Kirtland Egyptian Alphabet was then a compilation of four different documents: gold plate “reformed Egyptian” characters (1828), the Pure Language Document (1833), Phelps’s letter (1835), and finally, at the end of the Alphabet, the characters from the papyri (procured in July 1835).[33] (See Chart 6.)

Chart 6

This chart demonstrates that the Egyptian Alphabet is constructed of two different sets of characters. The first set is demonstrably not from the Egyptian papyri, since six of the characters in the first set match the shape and order of six of the characters used in the Phelps letter. They are not taken from the Egyptian papyri because the Phelps letter was written before they purchased it; they also do not match any of the extant papyri. The first set resembles and occasionally matches the characters from the Book of Mormon “caractors” document, but there were multiple Book of Mormon characters documents and the “caractors” copy was likely not the primary document they used to compile the list (though there are still several exact matches with the characters from “caractors”). Cowdery wrote in 1835 that when the Egyptian papyri first arrived, they compared them to “a number of characters . . . copied from the plates.” The second set of characters does exactly what Cowdery said that it did: it compared the Book of Mormon character to the papyri characters. They copied directly from the Egyptian papyri fragment that became Facsimile 1 in the Pearl of Great Price (Fragment of Book of Breathing for Horos). The original has three columns of Egyptian characters that they copied directly from.

Egyptian Grammar and Alphabet and the Book of Abraham

After producing the Egyptian Alphabet, they turned to producing a “Grammar and Alphabet.” They continued to examine characters from the papyri and showed sustained interest in Book of Mormon characters. This new extension of the project had “antecedents in the earlier Egyptian Alphabet documents, all of which are arranged in a similar fashion,” leading back to the Phelps letter.[34] They continued to work through the same methodological dilemma of incommensurability. The “grammar” demonstrated a system in which each line of characters could be deepened by degrees (the Pure Language Document reflects a similar kind of five-part meaning). It explained that any given symbol (say a character, like an “l”) has five parts of speech that can be multiplied five times if a line is placed above the character. The “Grammar” document explains: “The character alone has 5 parts of speech: increase by one straight line thus 5 X 5 is 25 by 2 horizontal lines thus 25 X 5 = 125; and by 3 horizontal lines thus: —125 X 5 = 625.” As a general system, the possibilities of translation multiply quickly, deepening with each line or character.[35] In fact, one character in Egyptian can extend to an entire paragraph in an English definition.

When Smith, Phelps, and Cowdery addressed the fifth or final degree, a single character is lined up with an entire pericope of the text of the book of Abraham.[36] This may actually be a representation for how God’s revealed word was deeper and more profound than the surface-level definitions of the first degree. Brian Hauglid has demonstrated that some of the Egyptian characters and their associated English definitions in the “Grammar” end up in the earliest manuscripts of the book of Abraham. In those manuscripts, there is a single Egyptian character that is lined up with an entire paragraph of English. This is not a definition of a word that can be extended in its explanation like a dictionary. Something else is going on besides a commensurable translation of an Egyptian character into an English word or phrase. One Egyptian character represents a paragraph of English prose, followed by a connected paragraph of English prose that is associated with another Egyptian character. What’s most important for the argument here about the secular binary is that revealed text from the book of Abraham is being associated with actual Egyptian characters. Whether or not the text of the book of Abraham is revelation or simply derivative of the Egyptian or the “Grammar and Alphabet,” it’s still clear that revelatory translation and secular translation created a binary that represented the translation.

What could be more incommensurable? The degree system in the “Grammar” distances the characters from a one-to-one translation and adds a metaphysical component of different ranges of meaning contained within a single character. A character may refer to a single word or an entire paragraph of English. At one point they start with the fifth-degree translation and work backwards as if they know the outcome and are trying to attach the English to an Egyptian character.[37] This leads to the fact that what seems (at first glance) to be a kind of one-to-one translation is not what it appears to be. In fact, it looks like Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon. He has the characters from the gold plates and a revelatory English text but no possible way to tell if they are commensurable. He nonetheless sees them as commensurable, as would eventually be demonstrated through the publication of the book of Abraham that included a precursor claiming that it was a translation of the papyri.

Modern translators can demonstrate that Smith, Cowdery, and Phelps did not know Egyptian, making their efforts in the production of the Egyptian Alphabet, the “Grammar,” and the book of Abraham an attempt to create one side of the secular binary by trying to perform a linguistic translation. The binary did not have to actually be a linguistic translation but it did need to be secular and non-metaphysical. Though they may have felt they were getting closer to a linguistic translation, their work on the “Grammar and Alphabet” further demonstrates the incommensurability of translation that they were getting closer to. They don’t appear to be any further along in becoming linguists or knowing Egyptian, but they show clear signs of believing that there could be a one-to-one correlation in Joseph Smith’s translations with Egyptian. The efforts toward real translation also went hand in hand with the production of new scripture, since at least part of the book of Abraham was produced during their examination and study of the Egyptian papyri.[38]

Yet, all of these efforts to produce a verifiable, commensurable translation are superseded by the actual products of the translation efforts. Translation remained revelatory, though it was identified as a secular process. Maintaining a systematic line of thinking, the relationship between the “Grammar” and the book of Abraham may be an example of the process and depth of meaning rather than definition. Their process of producing the Book of Abraham could easily make claim to the fact that Joseph’s translation came from the papyri, even if none of the characters on the papyri could be directly translated into any of the words in the book of Abraham. Given their previous experience with translation, this makes sense.

The translation of the book of Abraham exhibits the same kind of method and incommensurability demonstrated in the Book of Mormon translation. In the case of Joseph Smith’s 1828 translation, he produced characters to be translated by scholars, but he also apparently provided text from revelation or seer stones. Both show efforts to decipher the meanings of the characters, but both also rely on revelation to provide the English rendition.

This metaphysical process is somewhat different from what Smith and his disciples were attempting to do with the alphabets. Phelps’s May 1835 letter used known text derived from the “pure language” from which he superimposed characters next to the text. It was an effort to assign specific meanings to specific characters. Joseph and his colleagues followed the structure (five parts or states of one definition) of the Pure Language Document with the system of degrees they designed in both the Alphabet and Grammar and Alphabet in the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, but it is unclear whether the text of the book of Abraham came first by revelation or whether the characters inspired the text as an explanation.[39] Either way, it leads back to an underdetermined transference, or experience of divine communication that was derived from their exploration of a system associated with the Egyptian characters. This is like John Modern’s analysis in the fact that “true religion” is not being created by religion or religious experience, but instead it’s being created by the binary of religion and secularism or revelation and translation. Let me further demonstrate this binary with one more example.

Esotericism and Symbolic Translation

Scholars have rightfully compared the incommensurable translation described above with esotericism or attempts to understand Egyptian as a symbolic system that can only be delivered metaphysically.[40] Such an interpretation fits into a well-known intellectual tradition. Europeans struggled for centuries to make sense of Egyptian, developing it into a kind of cryptic language with no logical or systematic approach. The hieroglyphs represented mystery rather than clear expression or language. They treated the hieroglyphs like tiny pictures or symbols that could only be interpreted by ancient priests.[41] As Richard Bushman has argued, this symbolic school of Egyptian interpretation may reflect what Joseph Smith was doing in the Kirtland Egyptian Project.[42] If so, he was in good company. The Swedenborgians attached sacred meaning to the hieroglyphs, explaining that the meaning could only be accessed through divine means.[43] Bushman also points out that Smith used a similar approach to expand Hebrew later, in which simple words like “creation” became “a theory of creation.”[44] This symbolic interpretation of Egyptian drew on these mystical and esoteric theories of sacred language, demonstrating that what Joseph Smith was doing with translation was far less radical when placed within historical context. Egyptian was mysterious to everyone in the Western world.

However, Joseph and his colleagues did not buy wholesale into these mystical approaches either, since they show signs of using some of the nuanced academic approaches to Egyptian. French scholar Jean-François Champollion worked hard to break the Egyptian code by 1822. His breakthrough using the Rosetta Stone was the discovery that he disassociated the hieroglyphs with symbols and demonstrated that they represented sounds. Joseph Smith and his colleagues seem to be familiar with the implications of Champollion’s method. Beginning with Phelps’s letter, they created charts that reflected the comparative diagrams in Champollion’s work that juxtaposed hieroglyphs with phonetic scripts, a kind of comparison commonly found in the work of US-based scholars Samuel Rafinesque and Moses Stuart.[45] The Kirtland Egyptian Alphabet included names for the characters, pronunciations, and explanations. The pronunciations move distinctly away from the esoteric translation of Egyptian and represent the academic work of Champollion in the Kirtland Egyptian Projects by their use of phonetics.

Their exploration of Egyptian emphasized their interest in language but demonstrated more than any other project that their translations were underdetermined. They seemed to have accepted the fact that even if they were to break the code or understand the Egyptian characters, it wouldn’t offer them the pure language of God or even be a perfect reflection of the book of Abraham. Egyptian was certainly the entry point, but like other languages, it was corrupt in their minds, or at least deficient in its ability to deliver the pure communication of God—even a perfect one-to-one translation was still incommensurable in this respect. They did not give up on the usefulness of language, but rather they used the system it represented to see the depth of a particular message within a written language.

This gets us to the underlying tension of this article. It is clear that Joseph Smith knew that the ancient characters he was translating were inevitably incommensurable to the English translations that he offered. He did not devalue his revelatory knowledge, but rather accepted that it was more valuable than a linguistic translation that would also end up being incommensurable. Though Smith was producing translations by revelation, it still did not stop him from trying to create a system that explained and articulated that communication through language. The symbolic system of the Swedenborgians and others evoked a mystical experience by a priest, whereas Joseph was trying to give helpful precision and explanation to his translations. Comparable to Champollion’s phonetics, Joseph tried to identify the pronunciations and sounds of the characters, but then accepted the underdetermined nature of language and tried to develop a system of degrees to deepen the explanation and expand it further. In other words, Joseph did not want to accept the underdetermined nature of translation, but his struggle with it demonstrates that he was cognizant of the problem.[46]

The Prison of Language

Joseph Smith believed in a hierarchy of religious experience over language, but he couldn’t do without language. In fact, he explained, “Reading the experience of others, or the revelation given to them, can never give us a comprehensive view of our condition and true relation to God.” Yet, as he argued, “could you gaze into heaven five minutes, you would know more than you would by reading all that ever was written on the subject.”[47] Visions and revelations were his reality, while language was his prison. Joseph questioned the validity or possibility of finding synonyms, constantly turning back to religious experience for the reality of religious truth. In a letter to W. W. Phelps, Joseph articulately explained the impact of religious experience, writing that “the still small voice which whispereth through and pierceth all things and often times it maketh my bones to quake while it maketh manifest.”[48] Yet still lamenting that “God holdeth up the dark curtain until we may read the sound of Eternity to the fullness and satisfaction of our immortal souls.”[49] This metaphor uses contradictory sensorial expressions of access (sight, touch, and hearing) to demonstrate the withdrawn nature of that access by claiming that one could read sound. The problem of reading sound is a perfect metaphor to help us access what was happening in his translations. Joseph described this division between God’s word and our earthly reality as a prison. He prayed that God would “deliver us in due time from the little narrow prison almost as it were [total] darkness of paper pen and ink and crooked broken scattered and imperfect language.”[50] Perhaps what he never fully realized was that he was describing the ever-present secular tension of antebellum American religion and that his religion itself was dependent upon that tension and the secular binary.

Joseph Smith’s theory of translation couldn’t be expressed any clearer than when he explained that language was like a prison. He could never quite secure his religious and spiritual foundations without secularizing them through an incommensurable translation. Smith was aware of the incommensurability of translation yet he still sought commensurability. Within the binary of religion and secularism, religion became universal, as mentioned above.[51] Yet secularism also de-universalized parts of religion that were not “consistent with the basic requirements of modern society.”[52] In Joseph Smith’s translations, he accepted the secular discourse of translation commensurability and maintained the tensions of the binary with incommensurability to establish the legitimacy of his translations and Mormonism. In this way, his translations were both secular and religious.

[1] See Michael Hubbard MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’: Translating the Characters on the Gold Plates,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo: Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book, 2015), 83–116; Ann Taves, Revelatory Events: Three Case Studies of the Emergence of New Spiritual Paths (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016); Ann Taves, Fits, Trances, and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from Wesley to James (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999).

[2] Michael Hubbard MacKay, “Performing the Translation: Character Transcripts and Joseph Smith’s Earliest Translating Practices,” in Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith’s Translation Projects in the Development of Mormon Christianity, edited by Michael Hubbard MacKay, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Brian M. Hauglid (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2020), 81–104.

[3] Richard E. Bennett, “Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchell,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, edited by Dennis L. Largey, Andrew H. Hedges, John Hilton III, and Kerry Hull (Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book, 2015), 103–15.

[4] Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Robin Scott Jensen, “The ‘Caractors’ Document: New Light on an Early Transcription of the Book of Mormon Characters,” Mormon Historical Studies 14, no. 1 (2013): 131–52.

[5] This was recognized as early as 1829 when Cornelius Blachtely asked for the possibility of accessing the gold plates to identify a one-to-one translation. See Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon (Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book, 2015), chap. 12; Larry E. Morris, A Documentary History of the Book of Mormon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 375.

[6] For a remarkably clear examination and critique of the literature and evidences see Samuel Morris Brown, ”Seeing the Voice of God: The Book of Mormon on Its Own Translation,” in Producing Ancient Scripture, especially 146–67.

[7] Willard Van Orman Quine, Word and Object (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2013), chap. 2. In opposition to the indeterminism of translation, John Searle argues that this would lead to skepticism or the possibility of anyone ever understanding anyone else. John R. Seale, “Indeterminacy, Empiricism, and the First Person”, Journal of Philosophy 84, no. 3 (Mar. 1987): 123–46.

[8] The recognition of the problem of translation has deep roots in religious studies and the translation of liturgy, scripture, and sermons. See Willis Barnstone, The Poetics of Translation: History, Theory and Practice (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993); George Steiner, After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (London: Oxford University Press, 1975); Lydia H. Liu, ed., Tokens of Exchange: The Problem of Translation in Global Circulations (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1999); Christopher R. King, One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); Naoki Sakai, Translation and Subjectivity: On Japan and Cultural Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

[9] Talal Asad argues that to know what the term secular means is to understand the binaries that it creates. Secularims constrains the meaning and power of terms and concepts to their binaries and disallows a singular preference within a binary. Faith is solidified by its shift and delineating relationship with Reason. Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2003), 23.

[10] See Leigh Eric Schmidt, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000); James Delbourgo, A Most Amazing Scene of Wonders: Electricity and Enlightenment in Early America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006); Eric R. Schlereth, An Age of Infidels: The Politics of Religious Controversy in the Early United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013); Sarah Rivett, The Science of the Soul in Colonial New England (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

[11] John Lardas Modern, Secularism in Antebellum America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 7.

[12] Modern, Secularism in Antebellum America, 282. Modern’s thesis is important here in its ability to identify a network of ideas that animates individuals and society to replicate and authenticate particular normative conditions. This is important for the secular idea of translation or the notion of commensurability in translation, which this article demonstrates is set in opposition to incommensurability. Compare this sense of normativity to “hyper-normativity” in Peter Coviello, Make Yourselves Gods: Mormons and the Unfinished Business of American Secularism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 25 and 100. Talal Asad writes, “Only religions that have accepted the assumptions of liberal discourse are being commended, in which tolerance is sought on the basis of distinctive relation between law and morality.” Formations of the Secular, 182.

[13] Charles Taylor foundationally argued that secularism is a force that is opposed to religion and it is certainly not the opposite of religion. Religion in the secular age thrives, not just as a reaction to secularism but in part because of secularism. As Talal Asad has argued, secularism produces binaries that can easily be associated with good and bad religion, rational and irrational religion, both of which are relevant to the binary of commensurability and incommensurability in Joseph Smith’s translations. Asad, Formations of the Secular, 147.

[14] Edward Stevenson, “The Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon,” Millennial Star 48, July 12, 1886, 437.

[15] Quine writes, “An artificial example which I have used elsewhere depends on the fact that a whole rabbit is present when and only when an undetached part of a rabbit is present; also when and only when a temporal stage of a rabbit is present. If we are wondering whether to translate a native expression ‘gavagai’ as ‘rabbit’ or as ‘undetached rabbit part’ or as ‘rabbit stage,’ we can never settle the matter simply by ostension—that is, simply by repeatedly querying the expression ‘gavagai’ for the native’s assent or dissent in the presence of assorted stimulations.” “Ontological Relativity,” Journal of Philosophy 65, no. 7 (Apr. 4, 1968): 188.

[16] “History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834],” 161, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/167.

[17] “Revelation, 1 November 1831–B [D&C 1],” 126, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-1-november-1831-b-dc-1/2.

[18] “Revelation, circa 2 November 1831 [D&C 67],” 115, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-circa-2-november-1831-dc-67/2.

[19] Coviello argues that “secularism’s negative, its enemy, is not religion; it is bad belief.” This is framed first by the binary religion and secularism that moves to other binaries like civilizing and imbruting, or in this case, “God’s voice” and “humankind’s voice.” They thrive off one another, but appear without analysis to be trying to eliminate each other. Make Yourselves Gods, 27–29.

[20] “History, 1838–1856,” 162.

[21] Steiner, After Babel, 29.

[22] The scope of these visions is demonstrated in this passage by referencing them as including past, present, and future. “For he that diligently seeketh shall find; and the mysteries of God shall be unfolded unto them, by the power of the Holy Ghost, as well in these times as in times of old, and as well in times of old as in times to come; wherefore, the course of the Lord is one eternal round” (1 Nephi 10:19).

[23] “And also others who have been, to them hath he shown all things, and they have a written them; and they are sealed up to come forth in their purity, according to the truth which is in the Lamb, in the own due time of the Lord, unto the house of Israel” (1 Nephi 14:26).

[24] According to the Book of Mormon, John is the author of the book of Revelation in the New Testament.

[25] For Samuel Brown, he has firmly moved toward the translation as metaphysical.

[26] There four typical ways of interpreting Revelation, of which Joseph Smith does not conform to or attempt to conform to in his interpretation of Revelation in D&C 77. See Grant R. Osborne, Revelation (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament) (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2002), 20.

[27] Joseph Smith Papers, 2:214.

[28] Orson Pratt, “The Holy Spirit and the Godhead,” Feb. 18, 1855, Journal of Discourses, 2:342.

[29] There are multiple nonextant documents that included characters copied from the plates. The extant document includes some of them, but Phelps may have had a different copy or document than the extant document. The fact that these line up create an interesting situation. MacKay, Jensen, and Dirkmaat, “The ‘Caractors’ Document,” 131–52. See W. W. Phelps, Pure Language chart.

[30] Interestingly, notions of Adam and Adam-ondi-Ahman were added to Doctrine and Covenants (see changes in Doctrine and Covenants sections 27, 78, and 107) in early 1835 just before Phelps wrote his letter to his wife in May.

[31] Joseph Smith Papers, 4:53.

[32] Joseph Smith Papers, 1:345–52.

[33] For an example of contemporary comparison see Oliver Cowdery to William Frye, Dec. 22, 1835, copy in Oliver Cowdery Letterbook, 72, photocopy at Church History Library; Cowdery, “Egyptian Mummies—Ancient Records,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, December 1835, 235.

[34] Joseph Smith Papers, 4:112.

[35] The Grammar is “split into two parts, each of which is further divided into five subsections, called “degrees.” The degrees in each part appear in reverse numerical order. Part I begins with the firth degree and works backward to the first, then part 2 starts over with the firth degree and proceeds in the same manners.” Joseph Smith Papers, 4:112.

[36] See Brian M. Hauglid, “‘Translating an Alphabet to the Book of Abraham’: Joseph Smith’s Study of the Egyptian Language and His Translation of the Book of Abraham,” in Producing Ancient Scripture, 363–90.

[37] “Part 1 begins with the fifth degree and works backward to the first, then part 2 starts over with the fifth degree and proceeds in the same manner.” JSP, Revelations and Translations Vol. 4, 112.

[38] Hauglid, “Translating an Alphabet.”

[39] This scholarly debate continues to be waged primarily between Egyptologists (John Gee and Kerry Muhlestein) and others (like Robin Jensen and Brian Hauglid). Joseph Smith was determined that it came from God.

[40] For studies on semiotic translation, see Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976); Dinda L. Gorlée, Semiotics and the Problem of Translation: With Special Reference to the Semiotics of Charles S. Peirce (Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi, 1994).

[41] Richard L. Bushman, “Joseph Smith’s Place in the Study of Antiquity in Antebellum America,” in Approaching Antiquity, 17.

[42] Samuel Brown, “Joseph (Smith) in Egypt: Babel, Hieroglyphs, and the Pure Language of Eden,” Church History 78, no 1 (Mar. 2009): 26–65.

[43] Emanuel Swedenborg, A Hieroglyphic Key to Natural and Spiritual Mysteries, translated by James John Garth Wilkinson (London, 1874); Sampson Reed, New Jerusalem Magazine 4 (Oct. 1830): 69–71; and J. D., “Egyptian Hieroglyphs,” New Jerusalem Magazine 4 (Feb. 1831): 233–36.

[44] Bushman, “Joseph Smith’s Place in the Study of Antiquity,” 19.

[45] See Matthew J. Grey, “Joseph Smith’s Use of Hebrew in his Translation of the Book of Abraham,” in Producing Ancient Scripture; Moses Stuart, A Grammar of the Hebrew Language, 5th ed. (Andover, Mass.: Gould and Newman, 1835), 9–10 (charts no. I–III); Samuel Rafinesque, “Tabular View of the Compared Atlantic Alphabets & Glyphs of Africa and America,” Atlantic Journal (1832); Jean-François Champollion, Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1828).

[46] His late work on the Kinderhook plates demonstrates his distance from linguistic precision, but his continued prophetic and revelatory expressions show why he would be so intrigued by those plates without concern for a determinacy of language. See Don Bradley and Mark Ashurst-McGee, “‘President Joseph Has Translated a Portion’: Joseph Smith and the Mistranslation of the Kinderhook Plates,” in Producing Ancient Scripture.

[47] Joseph Smith, “Mysteries of Godliness,” Times and Seasons, Oct. 9, 1843.

[48] “Letterbook 1,” 3, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letterbook-1/15.

[49] “Letterbook 1,” 4.

[50] “Letterbook 1,” 4.

[51] Tomoko Masuzawa, The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 29–30.

[52] Asad, Formations of the Secular, 182–83.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue