Articles/Essays – Volume 42, No. 1

Roundtable on Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Web Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Editor’s note: The publication of Massacre at Mountain Meadows (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008) by Glen M. Leonard, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Ronald W. Walker, a history of Mormonism’s darkest hour, is itself a history-making event. A scholarly discussion of their book and its significance in Mormon and Western studies was held at the Salt Lake Public Library on September 5, 2008, sponsored by the Charles Redd Center for Western History at Brigham Young University, the Mormon History Association, the Tanner Humanities Center at the University of Utah, the Tanner Center for Non-Violent Human Rights also at the University of Utah, and the Salt Lake City Public Library.

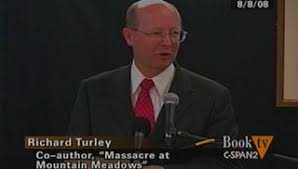

ROBERT A. GOLDBERG, professor of history and director of the Tanner Humanities Center at the University of Utah, chaired the panel. (See his review of Massacre at Mountain Meadows in the “Reviews” section, this volume). The three panelists were notable scholars with expertise in Western, Mormon, and Native American history. After their commentary and analysis of the book, one of its authors, Richard E. Turley Jr., responded extemporaneously. All four have edited transcripts of their remarks in that forum for publication here.

JOHN MACK FARAGHER is Arthur Unobskey Professor of American History at Yale University. His books include Women and Men on the Overland Trail (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1979); Sugar Creek: Life on the Illinois Prairie (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986); Daniel Boone: The Life and Leg end of an American Pioneer (Austin, Tex.: Holt, 1992); The American West: A Neiu Interpretive History (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Scott, Foresman, 2000) with Robert V. Hine; A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005); and Frontiers: A Short History of the American West (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008), also with Robert V. Hine. He teaches the history of the American West and directs the Howard R. Lamar Center for the Study of Frontiers and Borders.

PHILIP L. BARLOW, Arlington Chair of Mormon History and Culture, joined the faculty at Utah State University in 2007. He earned a B.A. from Weber State College and an M.T.S. and Th.D. (1988, with an emphasis on religion and American culture and on the history of Christianity) from Harvard University. In addition to articles, essays, and reviews, Dr. Barlow has published Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-Day Saints in American Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); The Neiv Historical Atlas of Religion in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), with Edwin Scott Caustad; and, as co-editor with Mark Silk, Religion and Public Life in the Midwest: America’s Common Denominator? (Lanham, Md.: Alta Mira Press, 2004). He is past president of the Mormon History Association.

DONALD L. FlXICO is Distinguished Foundation Professor of History, Arizona State University, in Tempe. He is a policy historian and ethnohistorian. His work focuses on American Indians, oral history, and the U.S. West. He has published numerous books—three of them with the University of New Mexico Press in Albuquerque: Termination and Relocation: Federal Indian Policy, 1945-1960 (1986); The Urban Indian Experience in America, (2000); and edited Rethinking American Indian History (1997). Other of his titles are Urban Indians (New York: Chelsea House Publications, 1991); The Invasion of Indian Country in the Twentieth Century: Tribal Natural Resources and America?! Capitalism (Norman, Okla.: University Press of Colorado, 1998); The American Indian Mind in a Linear World: American Indian Studies and Traditional Knowledge (New York: Routledge, 2003); Daily Life of Native Americans in the Twentieth Century (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2006); and edited Treaties with American Indians: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty, 3 vols. (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Santa Barbara, 2007); and An Anthology of Western Great Lakes Indian History (Milwaukee: University of Milwaukee-Wisconsin, 1988). His current research interests are Osceola: Patriot and Warrior of the Seminoles (forthcoming from Pearson Longman Press in 2009) and a textbook on American Indian history for Oxford University Press.

RICHARD E. TURLEY JR., assistant Church historian and recorder for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints since March 2008, previously served for eight years as managing director of the combined LDS Family and Church History Department, and before that (1986-2000) as managing director of the LDS Church Historical Department. In addition to Massacre at Mountain Meadows, he is also the author of Victims: The LDS Church and the Mark Hofmann Case (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), and editor of Selected Collections from the Archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press/Family and Church History Department, 2002). He is chairman of the editorial board for THE JOSEPH SMITH PAPERS series and general editor of THE JOURNALS OF GEORGE Q. CANNON series. He has been president of the Genealogical Society of Utah and vice president of the Small Museum Administrators Committee, American Association of Museums. He has also served as a member of the committee for Fort Douglas Heritage Commons, a “Save America’s Treasures” project; the Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board, National Historical Publications and Records Commission; and the Copyright Task Force, Society of American Archivists. In 2004, he received the Historic Preservation Medal from the Daughters of the American Revolution.

John Mack Faragher

The organizers of this forum have asked me to focus my response to the book on the question of violence, particularly frontier violence. I am by no means an expert in the history of Mormonism, or the history of Utah, or the Mountain Meadows Massacre in particular. Nor am I an expert on the history of frontier violence, although it is a subject in which I am now deeply engaged. I hope this evening to evaluate the book in light of that important context.

For me, the most important question in the book is this: What led “normally decent people” (128) to commit mass murder in a method and a manner and on a scale “so calculated, . . . so improbably sinister, . . . so premeditated, evil and cunning”? (199). The men who committed the atrocity at Mountain Meadows, they write, “were neither fanatics nor sociopaths, but normal and in many respects decent people” (128).

I want, first, to comment briefly on the choice of words here. “Sociopath” is not a clinical but a lay term, and I think it is something of a strawman. I don’t know of any historian who claims that the Mormon militia of southern Utah was made up of men who suffered from psychopathic personality disorders, although a number may well have been psychopaths of one form or another. And as far as “fanaticism” goes, this term, too, is somewhat slippery. The authors themselves characterize John D. Lee as a “religious zealot” (144), a man who saw himself as a “modern-day Joseph of Egypt” (158), and an instrument of “God’s purpose” (144). If that does not qualify Lee as a fanatic, I’d like to know what does. Indeed, they also quote Mormon Samuel Knight who referred to perpetrators Isaac Haight and William Dame in precisely those terms: as “fanatics” who were guilty of a “dastardly deed” (213).

So I think a more general and neutral terminology here, to start, would be better. For “normally decent people,” I would substitute the less presumptive, yet significant phrase of German historian Christopher R. Browning—”ordinary men.”

In order to address the problem of why and how ordinary men became mass murderers, the authors draw on several key studies in the sociology of collective violence. I am quite familiar with this literature; and in my opinion, they summarize it succinctly and utilize it fairly. “The conditions for mass killing,” they conclude, “demonizing, authority, obedience, peer pressure, ambiguity, fear, and deprivation—all were present in southern Utah in 1857” (xiv).

The first four of these conditions are, I think, much more important than the others. They are preconditions for collective violence, if you will. The literature clearly suggests that the single most significant factor in incidents of collective violence is the process the authors call “demonizing”—the classification of one people by another as “the other” (xiv). Devaluing, stereotyping, and finally dehumanizing the enemy makes mass murder possible. A great deal of historical work indicates that mass murder is unlikely, even impossible, without this precondition. The authors provide a good deal of evidence, most of it drawn from LDS sources, that the processes of demonizing Gentiles and enforcing hierarchical authority were both well advanced in 1857 Utah.

The other significant factor is a political structure of unassailable authority, absolute obedience, and significant peer pressure, allowing “errant leaders to trump the moral instincts of their followers” (xiv). The so-called Mormon Reformation of 1856 and 1857 seems to have played a key role in the development of such a structure of authority and obedience, and I think the authors spend too little time exploring this event.

I am not especially interested in the controversy of whether Brigham Young ordered the massacre, and I won’t speak directly to that issue; but I do wonder to what extent sermons from Young and other leaders that preached the necessity of blood atonement and the legitimacy of destroying angels created the context for vigilante and mob action. There is a difference between legal responsibility and moral responsibility, but both are legitimate subjects for the historian, and I’d like more of a discussion of moral responsibility. The authors do say that “the tough talk about blood atonement and dissenters must have helped create a cli mate of violence” (25), but they refer only obliquely to the Reformation-related murders in the community of Springville, despite quoting its militants as proclaiming, “We have declared war against the whole world” (109). During the Reformation at Cedar City where the Mountain Meadows massacre was plotted by local leaders, there was much talk of “blood-sucking gentiles,” of “pruning the ‘bitter branches'” from the LDS community, and the “need to obey strictly ‘those who are over us'” (25). Notably, when some Mormons at Cedar City refused to comply with Brigham Young’s order to send their cattle north to Salt Lake City, local commander John D. Lee threatened them with punishment, writing to Young that he was determined to enforce local discipline “if it need be by the shedding of the Blood, of those cursed, wicked, apostate, fault[-]finding wretches” (63; brackets are authors’). And after the massacre, perpetrator Nephi Johnson wrote about his fellow Mormon perpetrators, “A good many objected, . . . but they didn’t dare to say anything” (191). The authors might have asked more direct questions about the connections between the leadership and these local developments.

Informed by the historiography and sociology of group violence, my hypothesis would be that the Reformation of 1856-57 was a signal event in creating the conditions necessary for collective violence, first, by enforcing group discipline and ensuring that no one would disobey, and second, by sanctioning legal violence in pursuit of sanctified goals.

This second point—the moral sanction of lethal violence by LDS leaders—might have been emphasized more. The authors rightly note the initial pacific Mormon response to the murder ous violence of their opponents in Missouri and Illinois. The Mormons must be “exterminated or driven from the state,” declared Governor Lilburn W. Boggs in 1838 (12); and in 1844, an Illinois newspaper editorialized against the Mormons that “war and extermination is inevitable” (13). That Mormons tired of turning the other cheek is understandable, yet the way LDS leaders chose to partake of the rhetoric of “extermination” is also notable. The authors quote from Sidney Rigdon’s infamous Fourth of July oration of 1838: “We warn all men in the name of Jesus Christ, to come on us no more forever. . . . And that mob that comes on us to disturb us; it shall be between us and them a war of extermination, for we will follow them, till the last drop of their blood is spilled, or else they will have to exterminate us; for we will carry the seat of war to their own houses, and their own families, and one party or the other shall be utterly destroyed” (11).

Such moral sanction for lethal violence continued as an important part of Mormon rhetoric. On Pioneer Day 1857 in Cedar City, men unfurled the banner inscribed “A terror to evil doers” and a group of boys carried another with the title “Zion’s Avengers.” Isaac Haight, one of the leading perpetrators, declared, “I am prepared to feed the enemy the bread he fed to me and mine” (131).

To be sure, Mormons were fearful, rightly, of federal invasions—fearful, rightly, of yet another attempt to destroy them. But nothing justified focusing their fears on that immigrant train from Missouri and Arkansas. “I feel like fighting,” wrote Charles Jameson, who had been wounded at Haun’s Mill, “and if any Mob comes here, I feel like giving them the best I have got in the locker” (107). The authors quote another Mormon who itched to deliver to the immigrant wagon train “such a drubbing that, if the[y] survived, the[y] would never forget” (93; brackets are authors’). In their narrative of the events leading to the massacre, the authors offer compelling evidence of the mix of self-righteousness and lust for vengeance among Mormons. It was a lethal combination.

The plan of employing the Paiutes to do the dirty work of killing, particularly of killing the women and children, was despicable and shocking. But equally damning is the fact that the final massacre was planned as a cover-up of the initial crime. “If we let them go,” reasoned one local leader, “.. . they will raise hell in California, and the result will be that our wives and children will have to be butchered and ourselves too, and they are no better to die than ours” (189; ellipses authors’). In the end, self-interest and moral cowardice led to the logic of extermination. Men killed men, women, and children in cold blood, shooting people point-blank, cutting their throats, “butcher[ing]” people “like hogs,” in the words of one perpetrator, because they feared the consequences of what they already had done or condoned (201). Finally, it came down to the most ancient modus operandi known to man: the attempt to destroy the evidence.

In conclusion, I’d like to raise two more general critical points. The first is the context of violence. Early on, the authors point to the fact that nineteenth-century America “could be a violent place, particularly for racial, ethnic, and religious minorities” (xiii). This violence is a critical part of the historical context; and if anything, they greatly understate and underestimate that violence. Within the wider realm of American history, and particularly of frontier and Western history, I believe that this theme of violence is not sufficiently elaborated.

The United States did not experience the precipitous drop in homicide rates that took place with the creation of the modern state system in nineteenth-century Western Europe and Canada. Max Weber famously defined the state as the social institution claiming “the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory,” and there is good evidence to suggest that the rise of the modern European state was accompanied by a new code of civility that resulted in damping down the incidence of everyday lethal violence. But at precisely that time, the United States suffered through an intense crisis of the state, not only with the Civil War but also with the acquisition of vast western territories that were weakly governed for many years. The struggle over the legitimacy of the federal state and the loss or absence of confidence in the power and authority of that state contributed to massive outbreaks of both political and everyday violence. Homicide rates, which are the historian’s most reliable marker for generalized lethal violence in society, rose highest in the United States in the South and the Southwest, where the legitimacy of the state was most seriously contested. And indeed, those spatial patterns of the distribution of violence continued through the twentieth century and remain true today.

Frontiers were places of conquest that included the violent destruction of indigenous peoples, which Americans of the time called “extirpative war.” “From both necessity and hands-on experience,” writes historian John Grenier, “successive generations of Americans, both civilians and soldiers, made the killing of Indian men, women and children a defining element of their military tradition and thereby part of a shared American identity.” Frontiers were places that attracted reckless and violent men; the twin phenomena of lawlessness and vigilantism consistently characterized the American frontier.

Another aspect of frontier violence directly relevant to the Mountain Meadows massacre is that frontiers were, by definition, places where no group enjoyed a monopoly on violence. They were beyond the sphere of the routine action of centralized authority. The frontier context of the massacre was the intense and violent competition between two emergent political formations: on the one hand, the federal Territory of Utah, and on the other, the theocratic state of Deseret.

The frontier experience did much to set the United States on a different course from other democracies, retarding the development of central authority and a more civic and pacific populist temperament. No doubt the frontier contributed to a rich culture of liberty, but it also contributed importantly to the legacy of lethal violence. One of the issues is the place of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in this history of frontier violence. The significance of this subject is strengthened by this context.

The final issue I wish to raise is that we need to develop a more sophisticated approach, not only to the whys of frontier violence, but also to the hows. We need a better understanding of the patterns of socialization that trained Americans in violent behavior and taught them to see violent means as the most appropriate way of resolving conflicts. Even in a society that approves and sanctions lethal violence, there are non-violent men as well as lethally violent men. Legend lias it that Abraham Lincoln prevented a group of his fellow militiamen from murdering a captured Sauk soldier during the the Black Hawk War of 1832. But then there were others—the shooters at the final massacre at the Battle of Bad Axe, near present-day Victory, Wisconsin, where the Sauks attempted to escape across the Mississippi, the militiamen who shot down the Indian women and the elderly, the men who slaughtered the little children, declaring as they did so that “nits make lice.” Western and frontier historians need to explain how it was that such men existed.

We tend to take violence for granted. We tend to see it as a straightforward and uncomplicated phenomenon; but in fact, it is nothing of the sort. From the perspective of socialization theory, people are prone to violence when their primary groups—their families, their mentors, and significant others—see violence as acceptable, hold beliefs in support of violence, and are themselves violent. The socialization to violence is a developmental process that usually takes place at home during childhood. It commonly includes violent subjugation by an authority figure, the witness of the violent abuse of a loved one, usually a mother or sibling, and what amounts to the deliberate coaching in violent techniques. You have to learn to be violent. “You have to be carefully taught,” as the children sing in South Pacific. The child asks, “What can I do to prevent this kind of abuse except to use violent means to protect myself?” The individual tests that proposition by getting into fights, making threats, and developing a cynical attitude about institutions and authorities. Such individuals, if successful at developing a violent reputation, find themselves treated with fear and respect; they become comfortable with their violent persona. In the end, this process reproduces violent individuals.

Documenting such personal histories requires that we as historians penetrate the curtain that has been drawn across domestic life. This is difficult historical work, but it can be done. The authors tell us, for example, that John D. Lee wrote of being raised by an aunt whom he described as “a regular spit-fire.” He recalled, “I have been knocked down and beaten . . . until I was senseless, many times” (60). Lee learned about violence at home and was later accused of domestic violence by one of his wives. Significantly, the authors tell us that Lee was a participant at the Battle of Bad Axe where those Sauk women and children were deliberately destroyed (60). The Mountain Meadows massacre, it turns out, was not the first time Lee had participated in an act of collective extirpatory violence. I don’t know if the historical evidence exists to detail the violent training of the perpetrators of the Mountain Meadows Massacre; but until we do that kind of historical work, we will never truly understand why they found it so easy to turn to violence.

Philip L. Barlow

I congratulate the authors of Massacre at Mountain Meadows, along with their many associates who contributed. I also congratulate Oxford University Press, the LDS History Department, and the sponsoring LDS Church. This is a helpful, formidable piece of scholarship, sensitive to the memories of diverse victims and their heirs.

There will be time in other venues to critique this volume in a formal way. I construe my task here as something else: an opportunity to think about implications, both of the book and of the wretched event that prompted the book. What does the massacre teach us about Mormonism? What does it teach us about religion? What does the book’s appearance mean for Mormon studies? And what does it mean about the LDS Church and for the LDS Church that the Church opted to approve, facilitate, and fund at considerable expense this exhaustively researched and candid work?

It is appropriate to honor the achievement of the authors; it is important also to comprehend that their project represents an institutional decision and effort. As such, it is not merely an important work about a crucial episode in history; the book is historiographically historic. Coupled with the influence of Richard Bushman’s faithful, honest, and popular Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), the new Oxford book will change the sort of history that fairly mainstream Latter-day Saints will in the future encounter.

It was the authors rather than the Church who initiated the venture. Rumors that the Church helped underwrite the costs of publication at Oxford are untrue. And the authors—creditable men—insist that before launching their effort they reached an agreement with the Church that they would follow evidence where it led. It seems they have done so, despite swimming in a legacy a century and a half in the making of avoidance, obfuscation, and denial.

On the other hand, the book consummates an institutional effort in several senses. Despite the dust-jacket’s accurate listing of Ronald W. Walker as an independent historian, he, like Richard E. Turley Jr. and Glen M. Leonard, was in the employ of the Church during most of the research and writing. The project required ecclesiastical approval at the highest echelons. Without the blessing of the judicious and generous Church Historian, Elder Marlin K. Jensen, and the Quorum of the Twelve to whom he reports, the book in anything resembling its present form would have been impossible. Scholars acquired access to materials in the custody of the Church, including some in the vault of the First Presidency, that haven’t been made available to previous scholars, at least not for decades. Without the material support of the Church, the book would not have been accomplished with even twenty years’ work by these resourceful scholars. A small army of volunteer and professional researchers assisting the authors received necessary time and travel monies to explore countless threads at hundreds of repositories in fully two-thirds of the states in the country. They also had leave to meet—incessantly, year after year—to probe, generate inquiries, weigh evidence, and debate a galaxy of points and perspectives. This is not the way my books get written.

The resulting research seems exhaustive and honest. Few institutions could or would have done this so well. And yet our three authors had at last to write the book themselves, adjudicate among conflicting views of their research team, accent or dim various understandings, and withstand lobbying from those who did not want the book produced at all and, conversely, those who insisted it be done before it was done. It was back at the Tucson meeting of the Mormon History Association in 2002 when the authors announced the project and estimated a completed manuscript within a year or two. As co-author with Edwin Scott Gaustad of a comparably large project, the New Historical Atlas of Religion in America (Oxford University Press, 2000), I am reassured to contemplate that I am not the only writer to have missed a contract date by five or so years.

There has of course been resistance from some quarters to the publication of this book. Michael Landon drew my attention to a category of response I ordinarily ignore: an avalanche of hostile commentary posted online by readers of a balanced and thoughtful report by Carrie Moore of the Deseret News concerning the forthcoming volume (“Book Confronts LDS Tragedy,” July 19, 2008). Since the volume had not yet arrived in bookstores, these strong reactions came from people, often anonymous, who had not read a page but who often were condescendingly or bitterly sure that no book on the massacre authored by Church employees could achieve balance and honesty.

Researchers also encountered the tender nerves of descendants of the perpetrators of the massacre and others concerned for the image of the Church. Some of these lamented the reopening of an issue they want closed. It is long past time to move on, they said. “Let sleeping dogs lie.”

But these dogs have never slept soundly, not for serious students of history, not for the descendants of the victims, not for some Native Americans whose ancestors were conveniently blamed for the slaughter, not for thousands across the nation who have stood aghast when they stumbled into awareness of the episode, and, of course, not for those on a relentless campaign to impugn Mormonism. Literally and figuratively, the bones of the victims at Mountain Meadows have had a hard time staying buried.

Because the book is thoughtful, thorough, and frank, and because the painful enterprise of writing it was sponsored by the Church, many Latter-day Saints who read anything of the episode will read only this one book. This turns out to be the proper choice if readers limit themselves to a single treatment amid the torturous dozens that have appeared since 1873. It is just as well, for instance, that modern readers spare themselves the derivative sensationalism of Sally Denton (American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857 [New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003]), the nicely written pejorative errors of Larry McMurtry in Oh What a Slaughter: Massacres in the American West: 1846-1890 (New York: Simon 8c Schuster, 2005), or the flagrant propaganda of the film September Dawn (Christopher Cain, 2007). More avid students, however, will want to compare the work of Mssrs. Walker, Turley, and Leonard to Will Bagley’s Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), valuable despite the axe it grinds, and with David Bigler’s and Bagley’s documentary history: Innocent Blood: Essential Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, Fall 2008), important in making available primary documents relating to the outrage. Readers who want to know not only about the massacre, but about the work of coming to terms with it, will want exposure to Juanita Brooks’s standard account, The Mountain Meadoius Massacre (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1950; 2d ed., Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962), and Levi S. Peter son’s exquisite biography, Juanita Brooks: Mormon Woman Historian, (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988), and her heroic struggle to write on Mountain Meadows. One should also consider Shannon A. Novak’s newly published House of Mourning: A Biocultural History of the Mountain Meadows Massacre (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2008), a flawed but fresh approach by a forensic anthropologist whose primary concern has been the victims, including what she judges we can learn from their bones, inadvertently disinterred and briefly available to her. William P. MacKinnon’s recent and superb documentary treatment, At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 (Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008), is indispensable to the Utah War, apart from which the massacre at Mountain Meadows remains incomprehensible.

The success—and I am sure it will be a success—of the Walker-Tui ley-Leonard book will mean a number of things. It will likely encourage the Historical Department of the LDS Church to address other difficult aspects of its history in the future. The Saints and their leaders are apt to see that the Church will not be undermined by an authentic probing of difficult as well as inspiring contours of its own history. We can look for more treatments, perhaps of polygamy, perhaps of the history of blacks in the LDS culture. And because of Massacre at Mountain Meadows and its reception, we can expect that this future writing of the Mormon past under official sponsorship will be treated less defensively than has frequently been the case and with more concern for balance, truth, thoroughness, and probing inquiry.

Oxford’s new volume may have another effect. A good many collateral topics presented themselves to the research team in the course of the work and may result in fruitful future labor. Possibilities include a look at changes in Utah law regarding capital punishment as a consequence of first-hand accounts of John D. Lee’s execution, at the evolution of Brigham Young’s Indian policy, at additional episodes of whites disguised as Indians committing criminal acts, and at the incidence and effects of cattle disease in Utah and California and on the western trails in 1857 and during the 1850s generally. (Among the explanations proffered for the massacre has been the allegation that emigrants had poisoned Mormon cattle.)

Perhaps the most obvious likely outcome from the book will be a cultural catharsis, a shedding of corporate and local evasions. Our authors have gone beyond words like “unfortunate” or “tragic errors” to describe the event. More accurate and harrowing terms like “sinister plan,” “atrocity,” “murder,” and “desecration” lace these pages.

Catharsis will prove culturally healthy for the LDS community. Many Mormons, especially converts and those in their twenties and younger, have not heard of the Mountain Meadows Massacre; they are unaware of the albatross that has long hung about their collective neck in the eyes of thousands of outsiders. Other Saints have at least heard of the event but can scarcely grasp how it was possible, how it has anything to do with the Mormon people. More informed Saints know something of Mountain Meadows and absorb a remote, vague guilt, or else declare freedom from guilt: “men will be punished for their own sins”; “I wasn’t there.” Still others—descendants of Lees or Haights, for instance—have carried the stigma of the tragedy over generations. For decades after 1857, a number of parents in southern and central Utah steered their children away from alliances with these families, who in turn resented the scapegoating of the few for an action given aid or assent by many. Finally, sectors of Utah’s Dixie as a whole have sensed that the guilt was more diffuse yet, that those who carried out the crime were not atypical Mormons, that circumstances fated these with the opportunity to enact the hysterical and lacerated sensibilities of an entire abused people (Peter son, Juanita Brooks, 219-20.)

Catharsis for their heirs, then, will be healthy. But catharsis can in some situations be too thorough. It can allow neglect of important truths the authors of Massacre embrace. Of particular note is this: We humans, including LDS humans, who ordinarily strive for goodness, are capable of evil. We are, under severe duress, capable of demonizing and even destroying innocent others. Puritans striving for holiness at Salem Village in 1692—93 learned to their later horror that they were capable of murderous evil. So did the German nation, veterans and heirs of the 1930s and ’40s. American soldiers in Vietnam, at the hamlets of My Lai and My Khe, annihilated in 1968 three times as many victims as were murdered at Mountain Meadows. Some of the slain Vietnamese were shown to have been tortured, maimed, or sexually assaulted, some of the corpses mutilated. Not necessarily guilty of these last outrages, several Latter-day Saints were among the troops at My Lai, demonstrating that LDS soldiers have faced dilemmas about atrocities at various times, not only at Mountain Meadows.

Walker, Turley, and Leonard explore the recipe that can lead to the distortion of our ordinary moral sensibilities. The recipe includes conditions of extreme deprivation and an acute fear of rivals. Ambiguous messages from headquarters may add pressure and uncertainty. Minor wrongs transmogrify into what seems in tolerable wickedness. Rumors expand. Pressure builds to conform to group thought and group action against a perceived and pressing threat. People not of one’s own collective become “the Other”—devalued, demonized. The enemies are wicked; time is running out; preemptive action seems essential. An atmosphere of authority and obedience grows exaggerated, trumping the moral instincts of individuals. Voltaire observed long ago that if people can be made to believe absurdities, they can be made to commit atrocities.

There is, then, such a thing as beneficial discomfort. We Latter-day Saints have much for which to be grateful and proud: a culture in pursuit of that which is virtuous, lovely, and of good report; a heritage of sacrifice and resilience, of optimism and constructive efficiency, of meaning and service and faith. But if—in the interest of maintaining a “positive attitude” or “moving on” or burnishing our public image—we wholly suppress unpleasant memory and a healthy unease with national or tribal errors, we put ourselves in a dangerous place. We might find ourselves in a position, for example, of supporting the launch of preemptive war, a policy forbidden in Mormon scripture. If we neglect such lessons as the massacre at Mountain Meadows proffers, who knows what further entanglements, not necessarily entailing blood, await in a world sure to grow sporadically unsettled?

The massacre reminds us that Mormons are humans. This may have occurred to some of you previously. But I mean three things in particular: The first I’ve mentioned already. Although we are not deeply aware of it, under certain conditions we Latter-day Saints, like all others, are capable not merely of mistakes, not merely of sins, but of evil—of constricting, wounding, or destroying the innocent. This is a notion more amply explored in Protestant and Catholic than in LDS thought.

Second, Brigham Young was human, too. I am persuaded, as Will Bagley is not, that Young did not order the massacre. And I believe he was in diverse ways an admirable leader, whose general policy was to avoid confrontation unless outsiders “come upon us and compel us either to fight or be slain.” Nevertheless, under the duress of survival in an inhospitable land and of tensions between the federal government and a people who had historical reasons to fear violent outsiders, Young issued other orders and sermons that fostered a violent tone in the territory. Beyond well-known allusions to blood-atonement theology, for instance, and not many days after he dreamt of threatening federal judges W. W. Drummond and George P. Stiles with “oblivion,” and only two weeks before two cases of apparent vigilante assassination in southern Utah, President/Governor Young in February 1857 ad vised bishops and stake presidents in the South to be on the look out for two thieves thought to be traveling in their vicinity. If stealing were observed, he instructed local leaders (in a thrust toward summary extra-legal violence) to act expeditiously to eliminate the problem: “We do not expect there would be any prosecutions for false imprisonment or tale bearers left for witnesses.”

Such a policy was consistent with sermons he had preached for years, as with this, of April 8, 1853: “If you will cause all those whom you know to be thieves to be placed in a line before the mouth of one of our largest cannon, well loaded with chain shot, I will prove by my works whether I can mete out justice to such per sons, or not. I would consider it just as much my duty to do that, as to baptize a man for the remission of his sins.”

Only a few years before the events at Mountain Meadows, as many as one hundred women, married and unmarried, left Utah on account of liaisons with departing Gentile soldiers who had enjoyed hospitality in Salt Lake City. One soldier, Second Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry, had overtly courted Brigham’s daughter-in-law, Mary Jane Avers Young, with her encouragement, while her husband, Brigham’s son, was on a mission in Britain. An understandably livid Brigham Young offered blunt warning to any future soldiers coming to the vicinity “to prostitute [our women], to ruin them, and send them to the grave, or to the devil, when they had done with them…. I am after [such men] with the barbed arrow of the Almighty. To what extent? Let them intrude upon the chastity of my family, and, so help me God, I will use them up. . . . I would rather follow her to the grave, and send her home pure, than suffer my daughter to be prostituted.” Such rhetoric naturally affected the attitude of Young’s devoted followers.

Brigham Young was a human prophet-leader whose people were caught in a wrenching and precarious circumstance of repeated exile, then war and proto-war; I am in no position to judge him. His are nonetheless strong words in light of later blood spilt in the Territory of Utah. One can imagine Joshua anciently conjuring such language as Young did. It is harder to imagine Jesus doing so.

Third, the massacre and the new Church-sponsored book about the massacre may present to the Latter-day Saints the option of a different paradigm for construing their faith than that to which they are accustomed. In this alternate paradigm, the Church is not divine, marred only by the imperfections of its human members and leaders. Instead, one might think of the Church as consisting entirely of human beings, with all that such status can entail, who are trying to respond to the divine with which they have, in faith, been touched. It may seem a subtle distinction; I think it a crucial one.

An implication of this alternate model and of Massacre at Mountain Meadows is that there are proper limits to authority, obedience, and faith. LDS culture and teaching emphasize obedience; often it is presented as the first law of heaven. Adam obeyed for reasons he knew not, save he was commanded. Faith is cast as an unalloyed virtue; more faith is always good. Beyond most cultures, Mormonism has elevated notions of authority to great heights, and this is surely a part of its extraordinary success. Indeed, I personally work to honor, cooperate with, and exercise priesthood.

But Joseph’s revelations also provided for limits: unrighteous dominion dissolves authority (D&C 121:36-38). I can discern nothing virtuous about blind obedience or blind faith. Terrorists, fanatics, and fools of all sorts have plenty of both. Proper obedience, even in response to revelation, requires a thoughtful faith, which Alma 32 characterizes as a reasoned and experienced trust, developing organically by way of feedback and edifying results.

All humans, secular or religious, rely on selective sources of knowledge, although few humans are very deliberate about it. Secularists may imagine that their sources of knowledge are wholly rational and reasoned, but often it is the prestige of some authority figure or group, rather than deeply reasoned inquiry, which persuades them. This phenomenon is readily apparent in the way students sometimes argue about the relative merits of evolutionary theory or “intelligent design” as explanations for the earth’s character. Few of these students can articulate persuasively the evidence for their argument; they frequently rely on the prestige of the Bible or of scientists whose work they do not well understand. Religious understanding, in turn, may rest primarily on reason, scripture, living leaders, councils, tradition, intuition, personal revelation, community, or experience. Usually, even if unconsciously, it is a combination of several of these.

The authors of our book, analyzing disaster, point specifically to the realized danger of a theocracy where all power is concentrated in single or few hands. They seem to suggest that there may be a time to say no.

Twenty-first century Saints are not apt to be called upon under Church authority to participate in killing someone, though the religious principle of “obeying the law of the land” can be tricky business in an international church in a conflicted world. There are, however, other issues encountered in the Church where ecclesiastical policy grows in tension with the private sensibilities of Saints—Saints who are not winners and self-justifying agitators, but devoted servants, eager where possible to support, take counsel, and act constructively. It was so in the nineteenth century with the injunction to practice polygamy; it was so at the turn of the twentieth century with the ambiguous injunction to give up polygamy; it was so at mid-century with understandings of blacks and their roles in the Church; it has been so concerning women’s place in the home, in the world, and in Church councils; it is so with understandings of homosexuality and the policy of Church-sponsored activism against gay marriage. All these wrenching, complex issues imply questions about the relation of ecclesiastical authority and private conscience.

The publication of Massacre at Mountain Meadows marks the passage of time. We find ourselves in a new era in which the flowering of Mormon studies and the existence of the internet render it impossible for any institution entirely to fence its history while maintaining credibility in the wider society. The subject, honesty, and quality of Oxford’s book also proclaims that Mormon culture is maturing, is more confident, more prepared than at any time since the 1970s to be a genuine partner in the pursuit of historical understanding. The book will legitimize the impulse of many Saints to assert, as Juanita Brooks did more than half a century ago, that “nothing but the truth is good enough for the Church of which I am a member” (The Mountain Meadows Massacre, vi). The Church will not finally be undercut but will gain in credibility for at last coming to terms with an agonizing episode in its past, for demonstrating public regard for the victims and their heirs, and for showing a willingness to point to the culpability of its own people as opposed to the Piutes who, from the time of the tragedy, have labored under an unjust, wildly disproportionate judgment.

Some contemporary writers, such as sensationalist author Jon Krakauer in Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith (New York: Doubleday, 2003), come near to implying that violence inheres in Mormonism’s seeds, with today’s clean, cheerful, mainstream Church as a sort of polite and naive dilution of its dangerous original core that could arise again at any moment. Others construe the slaughter at Mountain Meadows entirely as an anomalous distortion, having nothing to do with Mormon principles; they literally cannot believe that the events at Mountain Meadows have anything to do with them. And the massacre is indeed a grotesque smear of Mormonism’s real intent, its typical and highest reaches, its contemporary consciousness and ways and aspiration. These comprise Mormonism’s dominant gene: the aspiration to be good—to seek, to experience, even to achieve and express the divine.

An authentic and prudent historical consciousness is nonetheless better served not utterly to forget a recessive gene in nineteenth-century Mormonism that partook of its time and inclined toward the violent under severe pressure. Most Saints will not be aware that the scars and wounds from brutal assaults and clashes with outside society during the nineteenth century ran deeply enough that Mormon sacred ritual and hymnody, even into the early decades of the twentieth century, urged heaven to avenge the blood of the martyred Prophet Joseph Smith. President Anthon H. Lund’s diary for November 8, 1902, captures both Mormonism’s dominant gene of restraint, forgiveness, and charity as well as the contrasting recessive gene, born of ordeal. Lund recounts how President Joseph F. Smith warned against yielding to impulses. Smith had related

how he at one time felt when a man in Iowa told him that he lived near Carthage where his father and the Prophet were murdered. This man said he was present. Joseph said when he heard this everything turned black and, when [the speaker] further stated [that] his day, the President said he could only think of that dastardly crime and that here was one of the perpetrators before him. What a relief to have the man say that he thought it was one of the most wicked crimes ever committed. . . . The President said I woke up as of a trance and found my knife open in my hand. Had he boasted of being one of the murderers I would have killed him. How thankful I was that I was preserved against such a fate. The Lord says “Revenge is mine.” Men must not take it themselves.”

In light of such tender, deep-seated, and dangerous nerves among the persecution-conscious Saints, it is little wonder that Juanita Brooks ran into obstacles and resentment before and after publication of her 1950 account of the massacre at Mountain Meadows. Unlike Fawn Brodie, who published No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet (1945; 2d ed. rev. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971) only five years before her, Brooks remained loyal to the Church. She wrote of Mountain Meadows under difficult circumstances, with roadblocks set before her both by her local Mormon society and by the specific actions of Church officials who looked askance at her enterprise and denied her access to important materials.

In 1979 KSL-TV aired a documentary featuring Juanita. In one scene she declared, haltingly, that upon publication of her book she had been disfellowshipped from the Church. (For years rumors had circulated to that effect.) Actually, she had not been. No Church court was ever convened. Yet as her biographer cast her television appearance, “her tongue at last spoke what her heart had felt.” She had been ostracized, shunned as a turncoat by her Mormon community even as she continued to attend services—disfellowshipped de facto if not by official edict.‘

Her book, welcomed among scholars and other readers, was greeted with near-total silence by Juanita’s ward, bishop, stake president, and almost all General Authorities who were asked by others about it. Few were those who would acknowledge that they had read it, and perhaps they did not. Juanita reported: “They evade it with the delicacy and solicitude they might show to a mother who has given birth to a monster child.”

We might wish the Church had stepped forward sooner to respect if not to honor her labor, which ultimately would have fostered healing. But it was too soon for an institution still emerging into respectability after generations of alienation from the American nation. And it was too soon for most Saints; close relatives of participants at Mountain Meadows were living and breathing around Juanita. Recoiling in such circumstances is a human and not merely a Mormon impulse. Brooks discovered that even the editors at Stanford University Press, eager to expose a Mormon atrocity, would not countenance her apt comparison to atrocities committed by American soldiers during the stress of World War II. They found the comparison to “our fine spirited soldiers” unpatriotic.

Among Mormons, the cool reception of Brooks, bearer of an unbearable truth, points to the fact that the massacre at Mountain Meadows was not only a tragedy for the slain victims and their families but also a trauma for the Mormon people, followed by fifteen decades of evasion and diffused familial and tribal guilt.

Two generations after Brooks’s heroic work, punctuated by the interval of the 1970s Arlington Spring, we have in hand a pivotal, honest, courageous, sensitive, thoroughly researched, finely crafted, institutionally sponsored book treating the same subject, at untold cost and labor. It is offered in the interest of truth-telling, catharsis, at least oblique self-examination, and rapprochement. The LDS Church History Department does not exist to multiply abstract facts. It exists to foster the purposes of the Church. Hence, the decision to support the historical exploration of this institutionally agonizing affair would not have been made unless the highest officials of the Church deemed it in the Church’s self-interest to do so.

They were right.

Donald L. Fixico

This work is monumental, a role model for scholarship. It is carefully conceived, carefully approached, carefully written and structured, carefully revised and revised and revised. (Those of us who write books don’t really write them—we rewrite and rewrite and rewrite them!) This particular book is the kind of work that scholars want to write, a pivotal book. Pivotal books cause change to happen, cause people to change their way of thinking, and cause us to address new questions. Tragedy at Mountain Meadows is such a book.

I want to address four main points: perspectives, questions, treatment of native peoples, and relationships. I was asked to comment, first, on whether this book succeeds in placing the massacre in the broader context of western history and of colonialism in the West, and, second, on the question of “Where are the Indians?” The answer to the question about the book’s success is an obvious “yes.” Also American Indians are part of the story here, even though they are not the main part.

In this regard, this book does something that a lot of Western scholarship does not do. When American Indians are involved, nearly always, they are in the past. I could be standing in a museum next to a non-Indian who is telling another person that “They’re all gone.” Even in our histories, native peoples are relegated to the sidelines, part of mythic history more than scholarly history. They have always been marginalized, relegated to a sidebar, or entirely left out of the story of the development of the American West. That was not right. Although we as scholars are trained to be objective, in our treatment of American Indians’ roles in the development of the West, we have failed to be objective and accurate. So it is with considerable appreciation that I see, in this book, evidence that we have finally reached a time in American Indian history in which native people have come to center stage. This book appropriately assigns many roles to the American Indians—victims, victors, losers in war, mercenaries, partners in civilization, pawns of imperialism. The Paiutes were both victims and pawns, used as allies. This book gives native people a part of the larger story of the American West, makes them part of the narrative, and gives them several roles.

In previous histories of Mountain Meadows, it was as if the Paiutes represented the whole population of native peoples at the time. This book does not make this mistake. This book makes native people present in two important ways: as they actually were there at the scene, but also in the way they were present in the collective imagination of the Mormon settlers. The fear and paranoia about Indian attacks on wagon trains, which the Mormons played up during the tense days leading to the massacre, makes Indians present in a way, even before they physically arrive in the action. You get the sense that the Indians were almost ready to attack on their own. From this account, one gets a sense of the presence of native people woven intricately in and out of the whole story. It points to the presence of Indians in the imagination. I applaud the authors for doing that, for paying attention to all of the ways Indians are part of the story. To write about American Indians is really difficult. This presence I’ve talked about is one in which there were presumptions about natives, but Brigham Young and the Mormons knew Indians better than many people did (and do).

Over the years, I have identified thirty-six stereotypes that people presume about Indians. There are six more that are positive and another six that are neutral; only six of them are positive, and only six are neutral. Even today, if two Indians are standing together on a street corner in Salt Lake City, people will wonder what they’re up to. Overcoming stereotypes and making native people seem real and complex is an important facet of this book.

The presence of natives in this book illuminates the nature of the relationship between Mormons and native peoples, the partnership. The groups shared land and shared the experience of uncertainty about the land. At some point, they both became vulnerable to westward expansion. American Indians had felt such vulnerability repeatedly. In 1970 Dee Brown wrote in Bury My Heart

at Wounded Knee about the feeling that a quarter of a million Indians must have had of facing east and imagining innumerable wagon trains coming toward you during the late nineteenth century. In fact, Dee Brown suggested to readers, “Americans who have always looked westward when reading about this period should read this book facing eastward.” Native people felt it constantly all the time, but Mormons were feeling it, too: Immigrants were coming, soldiers were coming. The native people felt that uneasy pressure constantly, so they shared that perspective with the Mormons, who were also watching this threat coming from the East.

Indians faced the real possibility of total destruction. There were at least 1,642 skirmishes waged against Indians between 1790 and 1895.” The amount of violence, the number of battles—it’s very large. I hope that no other native group has ever suffered or will ever suffer that much. I did a quick count of the battles. There were forty-one massacres between the 1500s and 1890, and that is probably a conservative estimate. Of the 41, Indians were the victims in twenty-two. So this concept of violence continued through the entire history of the settlement of North and South America by Europeans. By 1890, the year of the Wounded Knee massacre, there were only 250,000 Indians left in the United States from an estimated pie-contact total of 5 million; the genocide was nearly total. Brigham Young had felt that fear, the fear that what he had built would be wiped out. Mormons felt the same way—that what they had built would be dissolved.

It is also important to note that it was not only white settlers who were perceived as threatening by native peoples. There was a great deal of fear and suspicion of other Indians. The authors touched on it, but I wish they’d gone further into how native cultures operated. In Indian country, in the world of intertribal relations, it was tribe versus tribe. There were many longstanding Indian rivalries, not just between Paiutes and Utes, but also between the Chippewa and Dakota in Minnesota, Lakota and Crow on the northern Great Plains, Hopi and Navajo in Arizona, and Osage and Kiowa in Oklahoma, among others. These rivalries had existed for centuries; and by working with and understanding native peoples, Brigham Young had some sense of these intertribal tensions. I do see Brigham Young as understanding native peoples. He made efforts to meet with them and communicate with them. He told his people to go to them, learn their languages, and teach them to farm. In this way, he put himself in a precarious position; by sending Mormon settlers to areas adjacent to natives’ land and having them act as mediators in the Walker War of 1854, he put the Mormon community between the Indians and the U.S. government. It was agents of the U.S. government that had attacked native people in all parts of the country, and the Mormons could be seen as allied with native people against the government’s incursions in Utah Territory. Brigham Young was smart. He understood that they were allying Mormons with natives and used this relationship to his advantage; but by treating Indians as allies, he was also recognizing the power in them. They had power because they were an ally in the eyes of Brigham Young. In this way, perhaps, the Indians played more than a minor role.

I want to say a little more about Brigham Young and how he entered this understanding of native people and their reality. The authors do not say it because this isn’t their topic. But a major purpose in studying Indians should be to understand their reality. Native people believed in spirits and visions and ghosts. I’m suggesting that the native reality was a combination of the metaphysical and physical. Those of you who write and teach know that you get ideas when you’re not consciously working; the subconscious, metaphysical world intrudes on the physical one in this way. For native people, such metaphysical messages are a constant feature of their reality. And I think Brigham Young understood that. He not only understood the natives, but he treated them respectfully as allies, because he recognized their spiritual power as well as their political power. Native people also understood Brigham Young’s political position; it was a real partnership in many ways. However, the Indians were not simply trusting of the Mormons; Indians were skeptical and distrustful of relationships with non-Indians—just as they were with native peoples not of their tribe. Although there was a partnership, an alliance, between Mormons and Indians, it was always uneasy.

To conclude, I return to the idea of perspective, which is illustrated by this story. Once there was a man named Smith who could not keep up with his neighbor, Jones. Jones always had the best and the newest of everything. Smith determined to do something about this frustrating situation. In the classified ads of a newspaper, he saw an advertisement for a dog that could walk on water and thought he could finally get something that Jones did not have. So he got the dog and then invited Jones to go for a walk with him. They went toward the lake. Mr. Smith threw a stick out onto the lake and the dog walked across the water to get it. As they drove home, Jones said nothing. Finally, exasperated, Smith asked Jones if he had noticed anything about the dog. Jones said, “Yes, I noticed that he can’t swim.”

Many stories are altered by the perspective from which they are told; this book invites us to view this history from a new perspective.

Richard E. Turley Jr.

I’d like to thank these three notable scholars for their comments about our book. I suppose every author hopes to be read, and there is a certain expectation and hope that people will not only read but that they will understand. For many authors like myself, there is a great deal of humility in approaching a book when it has been read by three scholars of the caliber of our panelists; so I want to thank them for coming and for participating in a discussion of this horrible event in the history of Utah and of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that we call the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

As Dr. Faragher has reminded us, “The United States could be a violent place,” as we put it. And as he put it, that statement was very understated, very underestimated. That’s a theme he felt we should have developed more. It’s a theme we did develop in initial drafts to a greater extent. One of the constraining factors we had was the page count for our manuscript. There was a temptation to which we gave way over and over again to write at length about some of these topics that engaged us so much, only to realize, as we looked at the larger picture, that we could not continue dealing with everything at that pace. As one of my co-authors is wont to say, for every paragraph in the book, there were three or four left on the cutting-room floor. Ultimately, we concluded that we could only touch the tips of the icebergs as we walked across this ocean, with the hope that others would come later and develop for us many of these important themes. What was especially gratifying to me in listening to the remarks of our panelists was that they were able to identify so many of these themes. I don’t know how many graduate students or academics who might write about these subjects are in the audience; but if you are searching for a thesis or dissertation topic, you’ve heard several this evening!

I particularly like Dr. Faragher’s reference to “ordinary men.” If you’re familiar with the book he references, dealing with ordinary people in Europe eventually engaging in the unthinkable, you will feel a sense of discomfort. It was our intention that our book create discomfort, because, if we look at the Mountain Meadows Massacre from a distance, merely from a pedestal of righteous indignation, we miss much of its meaning. We tend to think of the people who carried out the crime as somehow categorically different from ourselves, as strangers capable of committing acts we ourselves would never do. And yet the history of violence suggests that the distance between ordinary people and those who commit atrocities is a very short distance. Our hope was that, in reading this book, people would understand the shortness of the distance.

One book I readnoted that we Americans particularly like our criminals to be so different from us that we can rest easy, believing that we ourselves would never do what they have done. Hence, we watch television shows in which criminals, having just tussled with police, look a little banged up and disheveled so that we can convince ourselves that people who commit crimes look different from us. They are so different from ourselves that we don’t need to worry about our own proclivity toward violence or evil. We hope that readers of our book will shorten that perceived distance immensely and recognize that all human beings, unless they check a natural tendency within themselves, may give way to violence under certain circumstances.

Dr. Faragher also raised the point about Mormon rhetoric and its influence on the Mountain Meadows Massacre. This is an extremely important point, because violence does not happen in a vacuum. The Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred against an environmental backdrop of the Utah War and the Mormon Reformation, and it’s very important for us to recognize that context because, in this distance between peacefulness and violence, there is a spectrum that goes from vilifying and demonizing to language that’s often used to characterize “the other” in the discourse of war. And it’s only a short distance from the discourse to war itself.

I also found it very interesting that Dr. Faragher would talk about the importance of having more information about the place of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in the history of frontier violence. We tried to look at the massacre not as just an anomalous event in Utah history, but rather as a part of the larger his tory of the West. We need far more work to be done on this aspect. How did violence in Utah compare to violence elsewhere? How was the massacre part of an overall pattern and texture of frontier violence? Dr. Faragher referred to the phrase often used by people who attempted the murder of native peoples or even their genocide: “Nits will make lice.” It’s the same phrase that one of the men at Haun’s Mill used when he justified shooting a young boy at close range/ You can see here that it’s not a huge distance from the language to the act.

I found Dr. Barlow’s remarks about the impact of this book on Mormon historiography quite interesting. He asked what this book means for Mormon studies. What we hoped, as we set forth, was that this work would give confidence and encouragement to scholars of Mormonism. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is, in our opinion, the most difficult subject in Mormon history. And our feeling was that, if we could confront this topic face to face and in a straightforward manner, with all of its horrors then people who write about Mormon history would feel able to confront virtually any topic. Our hope is that, in fact, this book will not only give way to a number of books and articles on the themes we’ve touched upon, but will also help to generate good scholarship on other difficult points of Mormon history.

Dr. Barlow reminded us that the book can create pain that leads to catharsis but that we need to beware that such catharsis doesn’t become too thorough. Humans are capable of evil; and if we, either as authors or as readers, forget that point or think that this book somehow gets it all out of our system, we will have missed one of the main points we hoped to make in the book.

I do think, as he said, that sufficient time has now passed that we can enjoy this flowering of Mormon studies, including the flowering of information about the Mountain Meadows Massacre. There has been a virtual renaissance of work on this subject over the last twenty years, and I think that is healthy.

Dr. Fixico talked about the Mountain Meadows Massacre and our book in terms of native peoples and native perspectives. As he uttered the number of 1,642 wars and skirmishes that have been carried out against native peoples, I thought how many other crimes have been committed against them. In the case of Mountain Meadows, an effort has been made to vilify them, to saddle them with a crime committed principally by white southern Utah men.

I want to make a particular point that the Paiutes, who from the very beginning were intended as scapegoats for what happened at Mountain Meadows, have suffered under a burden that needs to be relieved. I don’t mean to get too personal here; and for those who may recognize the circumstances I’m describing, I don’t intend to be offensive. I have sat with groups of people in southern Utah who continue to insist that the burden for the massacre should remain on the Paiute people. When I hear such statements, I say, as gently and as clearly as I can, “You need to give that up. It was your ancestors who were the principal aggressors in this event, [applause] You need to lift from the Paiutes the burden under which they have suffered now for a century and a half.” Another tragedy of the Mountain Meadows Massacre as it relates to native peoples was that, as Dr. Fixico pointed out, these people in southern Utah had been sent to befriend the Paiutes and to live among them. A relationship of trust was established, and that trust was violated in the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Now the anthropological literature is full of statements about whether the conversion to Mormonism of some of these Paiute peoples was nominal or whether it meant something more. I’m not here to discuss that topic, but I will say this: Some of those people who became the victims of this scapegoating were at least nominally Mormons. And so what you had here was a case in which some people who had developed a relationship of trust were foisting upon their fellow human beings, who were also their fellow Church members, the blame for something that they had done. That’s an abuse of authority that needs to be recognized.

And then I’ve thought about other events in Utah history that need further attention. Some attention has been given in the last several years to the Bear River Massacre. But for the Paiute people in particular, the Circleville Massacre is a topic that needs greater attention and greater candor in some circles.

Finally, I want to say that a book of this nature could not have been completed without the help of many, many people. We’ve tried to recognize people in our acknowledgments, but that is in adequate recognition of the truly amazing time and effort that many people put in—our colleagues, our research associates, our editors, our friends from across the country who sent us information, our many readers who gave us their insights from different points of view. I conclude, as I began, with gratitude to these people and to our panelists for being willing to grapple with what I think is the most difficult event in Utah and Mormon history.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue