Articles/Essays – Volume 47, No. 2

What Shall We Do with Thou? Modern Mormonism’s Unruly Usage of Archaic English Pronouns

This article is the first of a two-part series. The second article will examine what the usage of archaic pronouns can tell us about Book of Mormon translation theories.

What shall we do with thou? If this question grates on your ear, it may be because you recognize that thou is a nominative pronoun (a subject) and therefore never follows a preposition. If it doesn’t grate, then you are living, breathing evidence of the difficulties presented by archaic second-person pronouns in twenty-first-century Mormonism.

English-speaking Latter-day Saints have an uneasy relationship with archaic pronouns. Although we do not use thou, thee, thy, thine, thyself, and ye in everyday speech, we encounter them frequently in three very different contexts in our religious communication. First, we read them in scripture, both ancient and modern. Second, we encounter them somewhat randomly, in other religious texts—hymns, histories, and patriarchal blessings, for instance. Third, we employ them in prayer. In the second of these three contexts, we expect to see inconsistency. But if we look at the first and third carefully, we may be surprised to find that our usage of these archaic terms is not just uneven; it is problematic on multiple levels—enough to give a professional editor like me serious syntactic dyspepsia.

Given the lay of this particular linguistic land, let me offer a quick disclaimer. The purpose of the ensuing analysis is not to offer suggestions on how we should solve these usage inconsistencies. In some ways, we have quite effectively painted ourselves into a perplexing grammatical corner. Rather, my intent is to begin an exploration of certain trouble spots, so that Latter-day Saints become more aware of how the English language is used in the Church, and so that those whose responsibility it is to make far-reaching decisions regarding language issues have more information to work with.

For readers who wish for more detail regarding the early evolution of English second-person pronouns, I have included a brief appendix. At this point, however, suffice it to say that Old English morphed into Middle English by about ad 1100, Middle English gave way to Early Modern English in about ad 1500, and by this time second-person pronouns had settled into the pattern we see in the King James Bible—the singular forms thou and thee, and the plural forms ye and you. A few centuries earlier, however, second-person pronouns in many languages, including English, began a rather odd semantic shift that would complicate their usage and that would, in time, set English apart in this regard from the family of Indo-European languages and lead to the difficulties that Latter-day Saints experience today.

In about the thirteenth century, the singular second-person pronouns became a familiar form of address, used with children or persons of inferior rank, while the plural forms began to signify respect in addressing superiors.”However, “by the sixteenth century the singular forms [thou, thee, thy, thine, thyself] had all but disappeared from polite speech.”It is important for us to understand how this development came about, because it leaves English in a unique and awkward relationship with other languages, explains why LDS usage of archaic pronouns is so problematic (particularly in prayer), and raises significant policy questions for an expanding multilingual church.

The T-V Distinction

In their 1960 paper “The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity,” Roger Brown and Albert Gilman identified a distinction between second-person pronouns signifying either familiarity or formality. Although they focused on this distinction in English, French, Italian, Spanish, and German, it occurs in many other Indo-European languages as well. “The European development of two singular pronouns of address begins with the Latin tu and vos. . . . In the Latin of antiquity there was only tu in the singular. The plural vos as a form of address to one person was first directed to the emperor and there are several theories about how this may have come about.”

“Eventually the Latin plural was extended from the emperor to other power figures.”This created a dual means of addressing others, and in time tu was used primarily with intimates, peers, or those of lesser station and vos with those of a superior rank or social standing or with those who were socially distant though equal in rank. In order to speak of this distinction in a uniform way, regardless of language, Brown and Gilman used the first letter of the relevant Latin pronouns and thus referred to the informal or familiar form as the T form and the formal, respectful form as the V form. Later this dual pattern of address came to be known as the T-V distinction. Not only was this power semantic rather complex in how it determined which form was used in various situations, but it also evolved over time and was applied somewhat differently in each language and culture. In modern German, for instance, the informal singular pronoun is du, with a corresponding informal plural of ihr. The formal pronoun, however, which is both singular and plural, is Sie, and it is not derived from the plural second-person pronoun but is instead identical in pronun ciation and verb conjugation to the plural third-person pronoun sie (they). In spoken German, context alone specifies whether the speaker is addressing someone (second person) or speaking about others (third person).

In earlier times, parents addressed children with the T form while children addressed their parents with the V form. The nobility likewise used T with the common people, but the people used V in addressing the noble class. “In later years similar asymmetrical power relations and similar norms of address develop[ed] between employer and employee, soldier and officer, subject and monarch.”

In relationships of relatively equal power, where there was no superior or inferior, speakers generally used the same form with each other. “During the medieval period, and for varying times beyond, equals of the upper classes exchanged the mutual V and equals of the lower classes exchanged T. . . . For many centuries French, English, Italian, Spanish, and German pronoun usage followed the rule of nonreciprocal T-V between persons of unequal power and the rule of mutual V or T (according to social-class membership) between persons of roughly equivalent power.”Eventually, Brown and Gilman maintain, the power semantic that determined which pronoun was appropriate came into conflict with another semantic. They call this the solidarity semantic. Although two people may be unequal in power, they may, however, be from the same family, the same school, the same profession, the same military unit, the same employer, or the same political party. If the feelings of solidarity outweigh the sense of superiority and inferiority, then the mutual T or V is used. For instance, although in earlier times parents used T with their children and the children responded with V, members of the same family now address each other with T in almost all cultures and languages. And since World War II, the French Army has “adopted regulations requiring officers to say V to enlisted men.”These subtle shades of usage vary from culture to culture and shift over time within a given culture. For instance, when my wife and I visited Germany in 2006 to pick up our son from the same LDS mission where I had served thirty years earlier, I noticed a distinct shift to a generally more frequent use of the T form (du) among people of the same age than had prevailed when I was a missionary.This personal observation supports the assertion of Brown and Gilman that the solidarity semantic is gaining supremacy over the power semantic.

In terms of English linguistic history, three overlapping developments gradually unfolded. First, the nominative plural ye was replaced by the objective you. Second, you became the formal singular nominative pronoun (the V form), while thou was the corresponding informal (T) form. Finally, for various reasons, thou slowly vanished from everyday speech, leaving you as the only second-person pronoun for either subject or object, a development unique to English. For several centuries, the usage of thou and you as singular pronouns was governed by shifting conventions and became rather complex. A short summary of this evolving usage appears in the appendix.

Shakespeare, the King James Bible, and the Quakers

By Shakespeare’s day,the usage of thou, ye, and you was sometimes indistinct. While thou was gradually falling out of everyday usage, the distinction between ye and you was becoming increasingly ambiguous. “Ascham and Sir Thomas Elyot appear to make no distinction in the nominative, while Shakespeare says A southwest wind blow on ye And blister you all over!”

In Shakespeare’s works we find a variety of usages in the second person between characters of different rank. Some have claimed that this is an indication of the ambiguities that had entered the language by the sixteenth century, but The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language points out that “if we adopt a sociolinguistic perspective, readings of considerable interest can result,” including the dialogue between King Lear and his daughters. “In the opening scene . . . Lear’s daughters address him as you, and he addresses Goneril and Regan as thou (as would be expected); but his opening remark to his ‘best’ daughter, Cordelia, conveys special respect: ‘what can you say.’” But when Cordelia’s response displeases her father, he addresses her with an angry “But goes thy heart with this?”Similar intentional shifts in usage in Hamlet, Richard III, and Henry VI suggest that Shakespeare was keenly aware of the subtle shades of meaning that could be created with the skillful use of pronouns.

Perhaps the most in-depth examination of second-person pronoun usage in Shakespeare was conducted in 1936 by Sister St. Geraldine Byrne.She interprets the usage of second-person pronouns in Shakespeare’s plays in chronological order, scene by scene, and concludes that Shakespeare’s treatment of these pronouns is “Elizabethan usage at its height,” when you “had become the ordinary form in the average speech of the higher and middle classes, while thou generally endured in the speech of the lower ranks with no claim to refinement. Moreover, you had become the tranquil form prevalent in polite conversation, in cool, unimpassioned intercourse, whereas thou had come to connote an emotional content. Finally, you had become the accepted pronoun of compliment and honor, thou had persisted as the accepted pronoun of intimacy and ease.” Considering these intricacies in the Elizabethan usage of second-person pronouns, Byrne argues that “Shakespeare uses the Pronoun of Address with the acme of

consistency.”The purpose behind his usage “was that general desire to indicate grades of social position,” which in Elizabethan society included “the King and his court, the nobility and their retinue, the smaller country gentlemen, the professionals, the commercial classes, and the servant class.”Shakespeare’s kings, Byrne observes, shift between thou and you to portray subtle shades of social interaction and circumstance. “No ordinary men seem to have quite the same liberty of pronoun usage.”While Byrne asserts that Shakespeare’s usage is impeccable, it is also “in keeping with dramatic and artistic truth. . . . Sometimes, indeed, Shakespeare is primarily concerned with character qualities rather than social position,” and he “misses no opportunity to call the pronoun [thou] to his aid in the depiction of certain character qualities.”

Terry Walker has examined the usage of second-person pronouns in Early Modern English using three primary sources: drama comedy and transcriptions of both trials and depositions. While none of these sources can be said to represent real extemporaneous speech, transcriptions of legal proceedings or depositions come closest to giving us a picture of how people actually spoke. The primary problem with using drama as an indicator of actual impromptu speech is that it is a creation of the author. “Drama Comedy,” writes Walker, “is often seen as bearing a close similarity to everyday speech, and as a result has been the focus of many previous studies of thou and you. However, it has to be kept in mind that the dialogue is fictional: the text is constructed by an author. Moreover, the intention of the author is presumably to entertain, and the language is often manipulated, for example, for purposes of characterization and/or humour.”Thus, the usage of thou and you by Shakespeare and others may have been exaggerated or manipulated in other ways to enhance dramatic effect. Still, these studies do reflect in some way the patterns of usage that prevailed in earlier times and are useful to us as we seek to understand how our language has evolved.

As mentioned above, the subtle shades of meaning achieved by Shakespeare in his dramatic works were already being abandoned in his day in common speech and writing as thou gradually slipped from everyday usage and as you replaced ye in the nominative. This trend continued until thou, thee, thy, thine, thyself, and ye had virtually vanished from common speech. Thus, in today’s vernacular, the only usage of thou/thee is found in certain fixed phrases such as “holier than thou” or “fare thee well” that have come to us from our distant past, and certain biblical phrases that are quoted in appropriate circumstances (“Get thee behind me, Satan”). Linguists do not agree on an exact time frame when the now archaic forms dropped from common usage, but Oswald T. Allis suggests that the King James (or Authorized) Version employs them not because they were still in common use in 1611 but for the simple reason that they accurately reflect distinctions the translators found in the original Greek and Hebrew texts:

It is incorrect to claim that . . . “thou” represents the usage of the 1611 period when the AV [Authorized Version] was prepared . . . . The AV usage is not Jacobean or 17th century English. It is biblical English. The Greek of the New Testament like the Hebrew of the Old Testament distinguishes between the singular and the plural forms of the second person. The AV makes this distinction simply because NT Greek does so, and because that is the only way to translate the Bible correctly.

Allis makes a significant point here. Some modern translations of the Bible have dropped the distinction between second-person singular and plural to reflect a more contemporary vernacular. But in doing so, they have also erased subtle but important shades of meaning in some rather notable Bible passages. For instance, when the Savior says to Peter, “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan hath desired to have you, that he may sift you as wheat” (Luke 22:31), it is possible he is referring not just to Peter, since the pronoun is plural. (The italicized words in the King James Version, of course, indicate words that were not in the original manuscripts but were added by the translators to clarify meaning.) Interestingly, Joseph Smith, in his translation of the Bible, rendered this verse, “Satan hath desired you, that he may sift the children of the kingdom as wheat,” indicating the plural, albeit in the third person, and also removing or replacing the italicized words, as he often did. Likewise, when Jesus said to Nicodemus, “Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again” ( John 3:7), he was perhaps referring to the fact that all people must be born again, not just Nicodemus.

Pronoun usage in the King James Version, however, does not always follow the straightforward singular/plural or subject/object distinctions we may expect. Sometimes, particularly in the Old Testament, pronoun shifts occur, not because the translators were careless, but because the original Hebrew mixed singular and plural pronouns. Lyle Fletcher points out that pronoun shifts were sometimes intentional, such as when a speaker to a large group suddenly shifted from the plural to the singular. This shift had the effect of making the listeners feel that the speaker was addressing them individually.A significant example of this is Exodus 19:4–6, where the Lord speaks to Israel with ye, reminding them of how he delivered them from the Egyptians and wishes to make them a covenant people. But these verses are prelude to the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20, which are delivered using thou, as if the Lord is addressing each individual Israelite. A similar shift occurs several times in the Sermon on the Mount, where the Savior says, for instance, “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth; But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also” (Matt. 5:38–39). Fletcher correctly points out that although we cannot know whether these are accurate quotations from the Savior and from Moses, the ancient Hebrew and Greek texts did allow for this sort of pronoun shifting.

Fletcher also discusses at length the fact that there were over 300 instances of a nominative you in the 1611 Authorized Version, which may have been a reflection of the vernacular of the day. In an attempt to create a grammatically consistent King James Bible, however, most of these instances of the nominative you were replaced with ye by 1762. Interestingly, William Tyndale’s translation (created nearly a century before the AV, in the mid 1520s) contained no instances of the nominative you, although his personal writings contain frequent usage of this form. The reason for this may have been Tyndale’s emphasis on preserving clear lines between nominative and objective forms, as well as between singular and plural forms.

Of course, the King James translators drew heavily upon William Tyndale’s translation, including Tyndale’s use of thou and ye to distinguish between singular and plural in the second person. According to Frank Nolen Jones, thou and ye had already fallen from the everyday vernacular at that early date: “Tyndale knew of such subtleties, and he deliberately revived words that had already passed from common usage to handle faithfully the translating into English. In doing so, he actually created a special variety of English— a Bible English—for the purpose of clearly conveying the precise meaning. Tyndale thereby elevated the English usage by Scripture rather than accommodating Scripture to the English vernacular.”By replacing several hundred of Tyndale’s nominative yes with yous, however, the King James translators diluted that precision. While Byrne would dispute Jones’s assertion that Tyndale had to revive “words that had already passed from common usage,” the decision by Tyndale did create a scriptural dialect, which also had the effect of establishing a form of general religious usage that mirrored biblical English (though not precisely)and would persist for centuries. The use of thou in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, adopted by many churches in the Anglican Communion, likely added to the practice of addressing God with thou, even after the pronoun had passed out of the everyday vernacular.

If thou had not totally vanished from common usage by Tyndale’s day, or by 1611 when the KJV was completed, the beleaguered pronoun suffered yet another setback in the late 1640s with the rise of the Quakers. According to Brown and Gilman, “In the seventeenth century ‘thou’ and ‘you’ became explicitly involved in a social controversy. The Religious Society of Friends (or Quakers) was founded in the middle of this century by George Fox. One of the practices setting off this rebellious group from larger society was the use of Plain Speech, and this entailed saying ‘thou’ to everyone.”To the Quakers, using you with another person was both a religious and social corruption. They “disapproved of the way singular you had come to be part of social etiquette, and [they] accordingly used thou forms to everyone. This usage, it was felt, was closer to the way Christ and his disciples spoke, avoided unnecessary distinction, and was grammatically more exact.”Ironically, in the countries where English is spoken today, society has achieved the leveling and uniform informality the Quakers desired, but it has occurred with the formal, objective you replacing the other three second person forms. Meanwhile, some contemporary Quakers choose to cling to an archaic nominative thee that sets them apart as both peculiar and ungrammatical (thee is, thee were).

In summary, the disappearance of thou from everyday usage is not easily explained, but several factors seem relevant. First was “a general trend in English toward simplified verbal inflection.”Second may have been “a popular reaction against the radical ism of Quakers,”although it appears thou had already largely vanished from common speech by the 1640s. A third possible factor was the rise of the middle class and a general leveling of the classes as the Industrial Revolution displaced aristocratic institutions and relationships. A fourth factor may have been the evolving usage of thou to show contempt toward superiors or even equals.“The ‘thou’ of contempt was so familiar that a verbal form was created to name this expressive use. Shakespeare gives it to Sir Toby Belch (Twelfth Night) . . . : ‘Taunt him with the license of ink, if thou thou’st him some thrice, it shall not be amiss.’ In life the verb turned up in Sir Edward Coke’s attack on Raleigh at the latter’s trial in 1603: ‘. . . for I thou thee, thou traitor.’”

The relevant point for Latter-day Saints in this brief recounting of linguistic history is that thou was never used in everyday English to signify respect or honor. Quite the contrary, thou was actually abandoned partly because it had become a term of disrespect or contempt. Initially, thou signified only number (singular) and was used to address every individual, regardless of rank, until with the rise of the formal you it became the familiar or informal form. Finally, thou was abandoned altogether and replaced in the nominative by you, formerly an objective plural pronoun.

Thou in Religious Communication

Interestingly, in its entry on “Thou,” Wikipedia singles out the Latter-day Saint prayer tradition, which uses Thou to signify respect for deity. Grant Hardy points out that the reason Wikipedia singles out the LDS prayer tradition may be that we are the last major denomination to use the King James Version exclusively. “Archaic prayer language and the KJV—both of which make us different from most other English-speaking Christians—are intimately related.”Of course, some other Christian denominations still recognize the reverential Thou that is used in prayer, although its usage is gradually losing out to the more common You. One Baptist website, for instance, makes this statement about the use of reverential pronouns:

We who are familiar with, and use these pronouns in speaking to God, certainly should not be too critical of those, who, because of a limited exposure to traditional language and the widespread use of modern translations have difficulty in using such terms. But, if we understand the terms and appreciate the significance of using them in prayer to God, we should use them and encourage their use by others. We should treasure these special terms of reverence as part of the rich heritage we enjoy in the English language and not let them fade out of use. To do so will not only impoverish the English language, but also the prayers of God’s people.”

Other Christian websites are less conservative in their views, and some point out that people using these archaic pronouns can sound pompous, pretentious, or even irritating, especially if they mangle the grammar.

Bible translations have also become less conservative over time. The Revised Standard Version (1946), for instance, uses you almost exclusively, retaining thou only for addressing God (see John 17). This is an unusual pattern, since it reflects neither the uniform treatment of pronouns in the original manuscripts nor modern usage; it introduces instead a form of usage in which thou occurs only in prayer, but in no other instances, mirroring, interestingly, current Latter-day Saint practice. The translators of the New American Standard Bible (1971) made a similar decision, but in 1995 reversed course and have now eliminated all instances of thou, thee, thy, thine, thyself, and ye, as have the translators of the New International Version, the Good News Translation, the Common English Bible, the Contemporary English Version, the New Century Version, the New Living Translation, Today’s New International Version, the New Revised Standard Version, the New King James Version, and others. What this indicates is that Tyndale’s singular-plural distinction in the second person, which the King James translators preserved, has now been almost completely removed from recent versions of the Bible. With this shift, thou is becoming ever more scarce, even in prayers, and its correct usage therefore becomes ever more difficult, even for enthusiastic students of the Bible, unless they are using the King James Version. But most Christians today do not use the KJV, which places Latter-day Saints and particularly LDS missionaries in the awkward position of not speaking the same biblical language that their friends and investigators are accustomed to.

As pointed out above, during the period when thou was common in everyday usage, it was never used to signify respect or reverence. This meaning developed later, after thou had dropped from the common vernacular. Since it was preserved in the Bible, it thus became associated with religious speech rather than a mere signifier of either singular or familiar address. Eventually, as thou dropped even from other forms of religious speech, its use in prayer persisted; and this is likely the reason Latter-day Saints sometimes refer to it today as “prayer language” or “the language of prayer.” That thou has come to connote reverence, however, is purely an accident of English linguistic history. It is certainly not something God ever required, as evidenced by all the languages that do not have an archaic reverential pronoun and in which God is addressed in the familiar.

Joseph Smith’s Use of King James English

Even though many Latter-day Saints may think “the language of prayer” is in some way a revealed part of the Restoration, Joseph Smith would not have even been familiar with the term. It can be fairly easily argued that to Joseph the use of thou was not “prayer language”—it was simply religious language. Joseph did not use thou exclusively for prayers; he used it for religious speech in general. Thou appears frequently (although not consistently or exclusively) in the revelations he dictated and similarly in the Book of Mormon, in blessings, and in certain religious declarations and teachings (“Thy mind, O man! if thou wilt lead a soul unto salvation, must stretch as high as the utmost heavens, and search into and contemplate the darkest abyss, and the broad expanse of eternity—thou must commune with God”).To Joseph, and to others of his generation, this was merely the form religious speech assumed, presumably because it was the pattern preserved in the King James Version.

But Joseph was not well-educated. He was certainly no grammarian. Consequently, his use of these forms was uneven or (pun intended) unruly. For example, in the revelation that is now section 28 in the Doctrine and Covenants—a revelation to Oliver Cowdery—the second-person pronouns switch back and forth between singular and plural forms, even though the Lord is addressing only Oliver. Verse 1, for instance, which has been corrected in the current edition, originally read: “Behold I say unto you Oliver that it shall be given unto thee that thou shalt be heard by the Church in all things Whatsoever thou shalt teach them by the Comforter concerning the Revelations & commandments which I have given.”The initial “you” was later changed to “thee.” But even in the current version of D&C 28, the usage is inconsistent. Verses 1 through 6 use thou. Verses 8 and 9 use you. Verses 10, 11, and 14–16 revert to thou. This inconsistent usage appears in other early revelations that were directed to particular individuals.

What can we conclude from this? First, that Joseph was evi dently not receiving these revelations verbatim from the Lord. More likely, concepts were revealed to him, and he was then obliged to find suitable language to express these ideas. Doctrine & Covenants 1:24 supports this assumption: “Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding.” At least early in his prophetic career, Joseph expressed frustration over his inability to articulate in words the ideas that filled his mind. In a letter to William W. Phelps, Joseph lamented, “Oh Lord God deliver us in thy due time from the little narrow prison almost as it were totel darkness of paper pen and ink and a crooked broken scattered and imperfect language.”In essence, Joseph was doing his best to frame in his own language the inspired concepts he was receiving. But he was attempting to do more than just render these ideas in nineteenth-century American English; he had the added challenge of trying to express inspired communications from God in what to him was the already archaic religious terminology of his day, patterned after the King James Version.

Yet, as has already been discussed, neither Tyndale nor the King James translators attempted to introduce into their translations any sort of distinction between familiar or formal address, because the T-V distinction was not present in either ancient Hebrew or ancient Greek. So, in the King James Version, Jesus addressed the leper (“be thou clean”) with the same pronoun he used to address the Roman prefect (“Thou sayest it”) or his Father (“glorify thou me”). These three persons were equal in the Savior’s eyes in the only way that mattered linguistically: they were each one single individual. When he spoke to more than one person, he used the appropriate plural form (“Whom seek ye?”) except in certain instances, such as the Sermon on the Mount, where singular and plural pronouns shift in some sentences, possibly as an oratorical device to single out each individual listener in the group. But there was no special pronoun in the KJV that signified either respect or familiarity.

And this is the language Joseph Smith was trying to mimic in his religious writings. To Joseph, then, thou was not a formal, reverential form of address reserved only for prayer. It was simply the singular pronoun in the second person, and the fact that he used it unevenly is probably an indication of his lack of formal education, nothing more.

Book of Mormon Pronoun Usage

Perhaps the most persistent grammatical inconsistencies in the Book of Mormon revolve around the use of second-person pronouns, which is markedly erratic (but not uniformly so) throughout the book. Consider, for instance, Alma’s individual instructions to his sons, recorded in Alma 36 to 42—seven chapters of text abounding in second-person pronouns. Alma starts chapter 36 by addressing Helaman in the plural: “My son, give ear to my words; for I swear unto you, that inasmuch as ye shall keep the commandments of God ye shall prosper in the land” (1). Two verses later, Alma switches to the singular: “And now, O my son Helaman, behold, thou art in thy youth” (3). The next verse switches back to the plural, and Alma uses the plural pronouns ye and you throughout the rest of chapter 36 and most of chapter 37. Then, in verse 35 of chapter 37, he switches again to the singular: “O, remember my son, and learn wisdom in thy youth.” He stays with the singular in verse 36 and most of verse 37, but it concludes with “And if ye always do these things, ye shall be lifted up at the last day.” After a few verses of commentary, Alma resumes addressing Helaman in verse 43 with the plural: “And now, my son, I would that ye should understand that these things are not without a shadow.” The final verse of Alma’s instructions to Helaman is likewise plural.

Chapter 38 contains Alma’s brief commandments to Shiblon. Verse 1 starts in the plural: “I say unto you, even as I said unto Helaman, that inasmuch as ye shall keep the commandments.” But two verses later, in the middle of a sentence, he switches to the singular forms: “I say unto you, my son, that I have had great joy in thee already, because of thy faithfulness and thy diligence, and thy patience and thy long-suffering” (3). Verse 4 then continues with the singular: “For I know that thou wast in bonds.” But verse 5 reverts to the plural: “And now my son, Shiblon, I would that ye should remember.” The remainder of the chapter employs the plural.

But chapter 39, addressed to Corianton, begins with the sin gular, switches briefly to the plural, then returns to the singular: “And now, my son, I have somewhat more to say unto thee than what I said unto thy brother; for behold, have ye not observed the steadiness of thy brother, his faithfulness in keeping the com mandments of God? Behold has he not set a good example for thee?” (1). The next three verses employ the singular forms. But verse 5 switches to the plural: “Know ye not, my son, that these things are an abomination in the sight of the Lord.” The next four verses are exclusively plural, but in verse 10, Alma again mixes pronouns within the same sentence: “And I command you to take it upon you to counsel with your elder brothers in your undertakings; for behold, thou art in thy youth, and ye stand in need to be nourished by your brothers.” The same pattern, if we can call it that, holds throughout the rest of Alma’s instructions to Corianton; he switches back and forth seemingly at random between singular and plural, concluding chapter 42 with a final verse in which the two are again mixed: “And now, O my son, ye are called of God to preach the word unto this people. And now, my son, go thy way, declare the word with truth and soberness, that thou mayest bring souls unto repentance, that the great plan of mercy may have claim upon them. And may God grant unto you even according to my words. Amen” (31).

These seven chapters are unusual in the Book of Mormon, because they are instructions given to individual sons by Alma and are, therefore, all in second-person discourse. Most of the book, being a history, is related in the third person, with occasional quotations or snippets of dialogue in the second person. By my count, these seven chapters contain 81 of the 207 instances in the Book of Mormon where ye steps in inappropriately for thou, 46 of the 110 instances where you appears instead of thee, and 32 of the 58 instances where your replaces thy or thine.

The most comprehensive analysis of second-person pronoun usage in the Book of Mormon is Lyle Fletcher’s 1988 BYU master’s thesis, “Pronouns of Address in the Book of Mormon.” Fletcher not only analyzes all instances of pronominal shifting in the Book of Mormon, he also addresses pronoun usage in the Bible, the Doctrine and Covenants, and other writings of Joseph Smith. This comparison is valuable, for it enables Fletcher to compare pronoun shifts in the Bible due to Hebrew or Greek patterns with shifts in Joseph Smith’s scriptural and other documents. Fletcher’s final conclusion is that inconsistent usage of pronouns in the Book of Mormon is most likely a product of Joseph Smith’s linguistic tendencies rather than Hebraisms or other patterns that occurred in the original plate text.

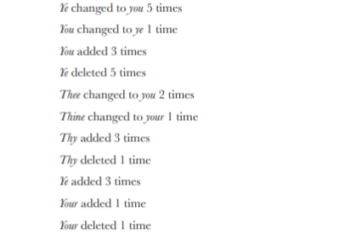

An indication that these inconsistencies may have been a product of Joseph Smith or at least the translation process and not the Nephite record is that Joseph himself corrected several of these grammatical errors in subsequent editions of the Book of Mormon. The Church has continued to follow Joseph’s lead in this, although very conservatively. Indeed, Fletcher enumerates the types of changes that have been made since the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon involving second-person pronouns. These include:

Ye changed to you 5 times

You changed to ye 1 time

You added 3 times

Ye deleted 5 times

Thee changed to you 2 times

Thine changed to your 1 time

Thy added 3 times

Thy deleted 1 time

Ye added 3 times

Your added 1 time

Your deleted 1 time

Thou changed to ye 11 times

“With regard to pronouns of address,” explains Fletcher, “most revisions in the texts have tended to consistency and modernization in usage of pronouns rather than inconsistent and archaic usage.”

While some pronoun shifting in the Book of Mormon may be a reflection of similar patterns in the Nephite language, of which we know little,most of these shifts are so random and erratic that they are more easily explained by looking to the translator’s lack of education or at least lack of familiarity with the intricacies of King James English. Indeed, the Book of Mormon usage of second-person pronouns is quite similar to usage in the Doctrine and Covenants. It is therefore tempting to conclude that the English text of the Book of Mormon originated with Joseph Smith, a largely uneducated translator who attempted to mimic King James language and who was only marginally successful since his own contemporary idiom did not employ the distinction between the singular and plural forms in the second person. Because this distinction had dropped from the English language, Joseph may have simply been unaware of what in earlier centuries had been standard usage. Indeed, in five instances, the word yourself appears in the Book of Mormon (Alma 39:9, twice; Alma 39:11; Alma 42:30; Mormon 1:4), a form that, technically, is impossible in a linguistic system that distinguishes between the singular thou/thee and the plural ye/you (it would be similar to themself ).

In Joseph’s defense, Fletcher points out that some of the Prophets’ better-educated contemporaries (such as Tennyson, Melville, and Scott) were also inconsistent in their use of the pronouns of address.In their day, as in ours, using archaic pronouns was no simple matter, even for well-educated writers. As I indicated above, it is tempting to conclude that Joseph Smith was responsible for the inconsistent pronoun usage in the Book of Mormon, but after looking at the text editorially and considering accounts of those who observed the translation process, I have come to a different conclusion. This will be the topic of the brief companion article to the present study.

For now, let me merely observe that if Joseph recognized that the text was imperfect and needed some corrections, the question might well be asked whether the Church should perhaps, in the spirit of improving the clarity of the text, correct obvious grammatical errors involving the use of second-person pronouns (and perhaps some verb conjugations) in a future edition of the Book of Mormon. The fact that Joseph himself made editorial corrections in later editions of

the book and that the Church has followed his example by making additional editorial changes over the years suggests that such edits are theoretically acceptable. Elder B. H. Roberts, operating on the perhaps mistaken assumption that Joseph formulated the English text, offered an argument for such corrections, which the Church appears to have followed, albeit conservatively:

There can be no reasonable doubt that had Joseph Smith been a finished English scholar and the facts and ideas represented by the Nephite characters upon the plates had been given him by the inspiration of God through the Urim and Thummim, those ideas would have been expressed in correct English; but as he was not a finished English scholar, he had to give expression to those facts and ideas in such language as he could command, and that was faulty English, which the Prophet himself and those who have succeeded him as custodian of the word of God have had, and now have, a perfect right to correct.

Following Roberts’s reasoning, those who are called in our day as custodians of the word of God have “a perfect right to correct” grammatical errors in the Book of Mormon, and it could be argued that achieving a grammatical consistency in the use of second-person pronouns would not only provide greater clarity in the scriptures, but would also simplify the work of Church translators whose task it is to transfer the meaning (and where possible the form) of these sacred works into languages that maintain a distinction between second-person singular and plural pronouns. For whatever reason, the Church has chosen a very conservative approach in correcting grammatical errors in the English text, although, as Lyle Fletcher indicated, several second-person pronouns have been corrected over the years. Yet scores of such errors still remain, and my understanding of Church translation procedures is that scripture translators are instructed to retain these grammatical errors in the various target languages, where possible. How well the translators follow this instruction would make a fascinating and useful study, though well beyond the scope of this paper. I did, however, perform a computer search in the German Book of Mormon of Alma’s instructions to his sons (Alma 36–42), which was examined above for inconsistencies in the English usage of second-person pronouns. Interestingly, in every instance where Joseph Smith dictated the plural ye but the context required thou, the German translators have corrected the grammatical mistake. Not once did Alma, in the German text, address one of his sons as ihr (plural); he consistently addressed each of them with du (the singular). A similar search of section 28 in the German Doctrine and Covenants shows the same result: the German translators have corrected every instance where Joseph Smith dictated a plural pronoun instead of singular in the Lord’s message to Oliver Cowdery. This raises the natural question of why the Church would correct pronoun inconsistencies in a foreign translation but retain them in the English original.

When considering the challenge of translating the English Book of Mormon into some 180 languages, another question arises: whether the Church should not only correct all the instances of incorrect pronoun usage in the book, but perhaps go one step further and follow the lead of modern Bible translations in changing all second-person pronouns in the Book of Mormon to you, thus simultaneously eliminating the inconsistencies and archaisms and in the process making this book of scripture more accessible to English speakers who are investigating the Church or who are newly baptized members. Fortunately, that is a decision I am not responsible for. So let us leave this topic and consider LDS usage of thou in nonscriptural settings.

“Solemn Language” and the Rise of the International Church

It appears that while thou gradually vanished from the common language, it survived in “sublime” or “solemn” language, including prayer. This is likely due to the predominance of the King James Bible. But as the Authorized Version has given ground to newer translations that do not use thou, thee, thy, thine, thyself, or ye, and as these archaic forms retreat ever further from the everyday vernacular, they are being replaced in many Christian denominations by the ubiquitous you even in prayer. It should be noted, however, that although thou may have been used for a time in religious or “sublime” contexts, until recently it never really car ried the reverential connotation that Latter-day Saints and others have assigned to it. It became a formal pronoun for solemn occasions or contexts, but its religious usage was based largely on its prominence in the KJV, and in both the Bible and other religious contexts it was never an honorific or reverential pronoun. It was simply the singular second-person pronoun.

An example of this “sublime” but nonreverential use of thou as a singular pronoun of address in LDS religious speech can be seen in its somewhat random persistence in patriarchal blessings. While an examination of the use of second-person pronouns in such blessings over the history of the Church would be a fascinating study, it is well beyond the scope of this paper. I will therefore offer just a few examples to shed light on its usage over time. The first patriarch of the Church was Joseph Smith Sr., the prophet’s father. With very few exceptions, the elder Smith used archaic pronouns in his blessings and, I might add, used them rather well, perhaps indicating that he possessed a better formal education in this regard than his better-known son. Now and then a stray you would creep into his blessings, occasionally he would misconjugate a verb, and, for some reason, a handful of his blessings used you exclusively, but for the most part he was very consistent in his usage.Interestingly, in the handful of blessings given by Joseph Smith of which we have record, the Prophet used neither thou nor you. He began his blessings with a statement such as “Blessed of the Lord is my brother Hyrum” and then proceeded to use third-person pronouns. Hyrum Smith, who succeeded his father as patriarch, was almost his exact opposite in pronoun usage. In his first blessing, to John Bennett, Hyrum used primarily thou and its various siblings, but in all subsequent blessings he used you exclusively. William Smith, who succeeded his brother Hyrum after the martyrdom, was very consistent in his inconsistency. He began almost every blessing with a statement such as “I lay my hands on your head and give you a blessing” but then switched immediately to thou, often within the same sentence, and retained the archaic forms throughout the blessing. I have seen only one blessing given by John Smith, Joseph Sr.’s brother, who succeeded William Smith. On August 12, 1853, Rebecca Williams, wife of the deceased Frederick G. Williams, received a second patriarchal blessing (the first had been given by Joseph Sr.). In this blessing, John Smith’s usage is the exact reverse of William Smith’s. He begins by saying, “I place my hands upon thy head,” but then switches to you immediately and never uses any form of thou again.

As these examples illustrate, there was no consistent practice among patriarchs in the earliest days of the Church, and usage certainly varied for many years thereafter until, in recent times, thou has likely vanished from patriarchal blessing vocabulary. A personal example may illustrate this general trend. My grandfather (born in 1899) was addressed in the first part of his blessing (given in 1919) with thou, but the patriarch suddenly shifted over to you and never returned to the more archaic (and likely less comfortable) form. By the time my grandfather became a stake patriarch himself, in 1966, thou was not part of his blessing vernacular. My own blessing, which I received from him in 1974, employs you exclusively. I should note, however, that Eldred G. Smith, the last patriarch to the Church, seems to have used thou in the blessings he gave and appears to have used it impeccably.The important point here, though, is that when thou has been used in patriarchal blessings, it has followed the scriptural pattern rather than our current reverential usage of the pronoun in prayer. It simply signifies the singular, but in a solemn or “sublime” setting.

All of this merely reinforces the idea that thou in English has a complicated and unique history, which makes its persistent prevalence in prayer troublesome in an increasingly international Church. For in most Indo-European languages, there is still a definite distinction between the formal, respect-laden second-person pronoun (the V form) and the informal or familiar pronoun (the T form). Thus, for example, in Germany children address their fathers with du (the T form) but address adults outside of their family with Sie (the V form). Significantly, however, they address God in prayer with du, the familiar form, not with Sie, the formal or respectful form. And so it is in almost every language that retains the T-V distinction. In English, had we not lost the familiar thou (the T form) in everyday usage, people would have still addressed God with thou—not because it would have signified formal or respectful speech (for this they would have had to use you), but because it would have denoted a familiar and familial relationship. The disappearance of the T form in English is the effect of the solidarity semantic prevailing over the power semantic. Indeed, the solidarity semantic prevailed so completely that today we have no power semantic.

When the T-V distinction vanished from English centuries ago, it left us without a distinction between formal and informal in second-person pronouns and, similarly, without a distinction between singular and plural. We have only you, which first displaced ye as the nominative second-person plural and then displaced thou and thee as the nominative and objective forms of second-person singular. In English, all speech has been flattened so that there is no power semantic at all. There is only solidarity. So, if we wish to address God in either a familiar manner (as do speakers of most other languages) or even in a formal manner, the only pronoun available to us, in a practical, everyday sense, is you.

Apparently, though, at some point during the period when thou was falling out of even common religious speech but was still employed in prayer, the notion gained popularity that thou was a reverential form of second-person address, perhaps because of Jesus’s pronouncement in the Sermon on the Mount, “After this manner therefore pray ye: Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:9–10). But, as already indicated, this was simply the singular form of the pronoun, and Jesus used it with ordinary mortals three verses prior to the Lord’s Prayer: “But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet” (Matt. 6:6). Thou is not reverential in the King James Version. It is merely singular. But because these singular pronouns dropped out of common speech, including religious or “sublime” speech, and appeared almost exclusively in biblical passages, they retained a religious connotation, and any reverential meaning they subsequently assumed went far beyond the intent of the King James translators or, especially, of the initial authors of the books in the Bible. Indeed, we might well ask, if Jesus did not address his Father with special reverential pronouns and did not teach his disciples to do so, why should we? John W. Welch observed of the Savior’s prayers, “Where he found people calling upon God with abstract, distant titles, Jesus introduced a homely, personal word, Abba. This word, important to the earliest Christians (see Gal. 4:6, Rom. 8:15), translates simply as father; but it is actually slightly less formal than that and contains a flavor of familiarity and trust.”If we, by contrast, persist in using the archaic second-person-singular pronoun to address deity because we believe it signifies respect and honor, there is no historical or linguistic or even scriptural backing for this practice, and most Church members who are native speakers of other languages simply cannot conform, because they do not have archaic forms that signify respect and honor. Indeed, the evolution of the reverential thou in English is not a manifestation of the T-V distinction. It is instead the exact opposite of the T-V distinction, which places English in an awkward and irreconcilable relationship with every language that retains the distinction between the formal and informal second-person address.

The Difficulty Factor

Because of its uniqueness in the family of languages, this odd English linguistic development, complicated by Joseph Smith’s uneven use of singular and plural pronouns, creates myriad translation difficulties in the Church. Translation challenges, however, pale in comparison to the confusion thou produces in non-English speakers when instructed to use a special “language of prayer,” a directive they cannot comply with. But perhaps the most significant drawback to our use of thou is practical. To put it bluntly, the biggest problem with using Thou in prayer is that almost no one in the Church gets it right consistently, and the Church does not seem inclined to teach correct usage. While Church leaders admonish members occasionally to use the language of prayer, none of them ever offer any specific instruction on how to do this. From time to time, an adventurous scholar or editor has undertaken such a task, but always with negligible effect. I speak from experience here.

Several years ago, while working as an editor at Church magazines, I wrote an article explaining how to use “prayer language” correctly. It covered such topics as the difference between thou and thee, regular verb conjugations with the pronoun thou, irregular verb conjugations (“thou art,” “thou shalt,” “thou wilt”), when to use thy and thine, and the difference between dost and doest. The need for this article was widely acknowledged among the editorial staff, but in the end it was deemed by Correlation to be unpublishable because terms such as conjugation were considered too technical for Ensign readers.The article was later published by BYU’s Religious Studies Center in The Religious Educator,and I hope it has been somewhat helpful to seminary and institute teachers as they try to help young people learn the prescribed language of prayer in the English-speaking Church. But Correlation’s point is worth considering. If “prayer language” is so complex to English speakers, who encounter it primarily (and somewhat erratically) in scripture, that even a straightforward how-to article explaining its proper usage is deemed too technical for an audience of adult, educated readers, then perhaps we ought to consider joining the majority of non-English-speaking Church members in addressing our Father in Heaven in more familiar, familial, and grammatically uncomplicated terms.

I am sympathetic with Correlation’s concern. Because archaic pronouns and verb conjugations are so difficult to master, almost no one in the English-speaking Church uses “prayer language” correctly. Joseph Smith was not alone in his struggles to accurately mimic the language used in the King James Version. Modern Mormon usage is as unruly as anything Joseph ever dictated. Listen carefully to any prayer in any LDS meeting, and you will probably hear misconjugated verbs or mixed pronouns. Prayer language is certainly a stumbling block for new converts, who have not grown up hearing King James English, but even General Authorities routinely make grammatical errors in opening and closing general conference sessions with prayer. And prophets also sometimes struggle with these archaic forms in temple dedicatory prayers, even though they have the added advantage of writing these prayers out beforehand.

But this is an issue that reaches beyond obvious grammatical difficulties or usage inconsistencies. It involves questions more vital than whether our missionaries are able to teach people in a vernacular they are comfortable with. There are ethical dimensions to this matter of archaic pronouns that touch upon the central tenets of the gospel. Using archaic pronouns correctly, or even mostly so, can create a mark of distinction for members who were raised in the English-speaking Church (and, likely, in middle-class, educated environments), setting them apart from converts, members who are less educated or less materially successful, and, of course, native speakers of other languages. This is an issue that can divide the Church into subtle classes, a social condition the Book of Mormon warns against repeatedly.

A Dual Dilemma

So, what shall we do with thou? This is not an easy question, but thou is becoming an increasingly troublesome matter in an increasingly modern, multinational, multilingual church. This question is made more difficult by the fact that we use thou, basically, in two different contexts, and we use it not only incongruently between those contexts, but we also use it inconsistently within each of the contexts. In scripture, we use thou merely to signify singular, as opposed to the plural ye, and yet in our uniquely LDS books of scripture, this usage is grammatically uneven. In the nonscriptural context, we use thou primarily in prayer, and we use it in a highly specialized way, to denote respect for deity, a convention that does not even exist in scripture. Unfortunately, because this specialized speech employs archaic forms, our usage is grammatically chaotic here too. Additionally, this specialized usage is unique to English and comes trailing clouds of historical ambiguity.

Generally speaking, there are two opposing ways of looking at language usage. The linguist is interested primarily in how language is used and is not really concerned with correcting that usage. Indeed, to the linguist, there is often no correct or incorrect usage. There is just language and the way people speak it. The linguist, for example, would find Joseph Smith’s shifting pronouns in the Doctrine and Covenants fascinating but not disconcerting. The editor, by contrast, is concerned with correct or at least effective usage. In order to communicate ideas effectively, the tool of language must be used according to certain rules and conventions. If it is not, then meaning is compromised. In the spirit of full disclosure, as a professional editor, my own bias should be obvious. I understand quite well that inconsistent language usage handicaps communication. I believe that our inconsistent usage of thou, in two different ways, hampers our ability to communicate and understand truth effectively.

That said, I must admit that bringing grammatical consistency and linguistic congruity to the two contexts in which we currently employ archaic pronouns would be a monumental project, somewhat akin to enforcing the adoption of the Deseret Alphabet. So, how can we possibly make sense of this peculiar linguistic inheritance the English language and our own history have bequeathed to us? I don’t pretend to have the answer to this question. But leaving things as they are certainly makes as little sense as any other option.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue