Articles/Essays – Volume 42, No. 4

What is Mormon Cinema? Defining the Genre

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Latter-day Saints made their first known cinematic appearance in 1898 in Salt Lake City Company of Rocky Mountain Riders, part of a series of very short motion pictures depicting American troops in the Spanish-American War. Since then thousands of films and television programs have dealt with Mormonism; at present the Mormon Literature and Creative Arts database lists 4,591 such items. This vast corpus includes a broad array of styles and subject matter, with motion pictures by non-Mormons, by Church members, and by the institutional Church. The diversity of content is evident in titles such as the independent missionary feature God’s Army (2000), the inspirational drama Windows of Heaven (1963), the anti-Mormon video The God makers (1983), the cult favorite Johnny Lingo (1969), the prosaic instructional film Teaching with Chalk (1956), and even the temple endowment, which was first presented on film in 1955. Fiction films, documentaries, instructional pieces, experimental works, filmed sermons and presentations, and even home movies all hold an important place in the historical corpus of Mormon film.

Since the 1910s, various terms have been applied to Mormon ism’s cinematic tradition and its various components: “Mormon cinema,” “LDS cinema,” “BYU films,” “Church films,” “seminary videos,” “Sunday School films,” and so on. These terms have been historically mutable. A “Mormon film” in the 1910s was a vastly different object than a Mormon film in each of the subsequent decades.

In 1912, for instance, the trade journal Moving Picture World ran the headline “Mormon Pictures in Demand,” yet the pictures in question were the sensational 1911 Danish film A Victim of the Mormons and six similar anti-Mormon productions that followed quickly in 1912, illustrating what the general public thought constituted a Mormon picture at the time. But by 1928 the Cleveland Ohio News christened the film All Faces West, produced primarily by non-Mormons under official guidance from Church leaders, “the first Mormon picture,” demonstrating a changing public perception. New manifestations of Mormon cinema could be seen in 1940 when Twentieth Century-Fox released its large-scale production of Brigham Young, in 1953 when the Church established a Motion Picture Department at Brigham Young University, and at other times until 2000 when Richard Dutcher released God’s Army. At that point his website called God’s Army “the first . . . Mormon film,” and commentators quickly agreed. As one example among many, in 2003 BYU’s student newspaper the Daily Universe called Dutcher “the creator of the first LDS film ‘God’s Army.'”

If both A Victim of the Mormons and God’s Army could be hailed by the press as preeminent examples of Mormon cinema in their day, then it seems profitable to examine just what the term means, both historically and now. Before doing so, however, two important questions must be addressed. First, what can we gain by approaching Mormon film from a taxonomical perspective? Second, given the wide diversity of individual films (doctrinal, comedic, nonfiction, dramatic, anti-Mormon, etc.) and the plethora of generic labels (Church films, Mormon films, LDS films, etc.), each with its own connotation concerning production, content, and audience, is it possible to speak of one monolithic Mormon cinema, or is it a blanket term covering several distinct traditions?

To answer the first question, there are many potential benefits to filmmakers and critics in identifying the center and the periphery of Mormon film. Many of these are endemic to the films themselves; for example, understanding Neil LaBute’s relationship to Mormonism provides greater insight into his work. But other benefits move beyond the films to deal with the Church’s place in the contemporary world. Mormon cinema, in fact, can often be seen as a synecdoche for all of Mormon society; along with music and temple architecture, it is the most prominent Mormon art form, continually invoked by the Church in its public relations and proselytizing efforts. Church leaders and members obviously believe that motion pictures can be an effective means of shaping public opinion. Hence, understanding the films that the Mormon community holds up as representative of itself, as well as those it rejects, increases our comprehension of Mormons’ self-perception and self-presentation to the world. Likewise, understanding what films outsiders have used to approach Mormonism helps us situate the Church in its broader social context. Thus, understanding Mormon film as a genre helps us comprehend the entire Mormon movement and its social milieu, again both historically and at present.

Answering the second question—what is Mormon cinema?—is more difficult. As mentioned, the term has constantly shifted, avoiding any single definition. However, Mormon film does have components in common with film genres, certain ethnic cinemas, and even national cinemas, among other precedents. It can therefore be useful and not inaccurate to describe Mormon film as a genre, or at least approach it from that perspective. To be more accurate, however, we must define Mormon cinema as a religiously based ethnic cinema that is continually developing characteristics of an actual genre or even multiple genres. Thus, positioned in the interstices between genre and ethnic cinema, Mormon film exhibits characteristics of both but complete adherence to neither.

To examine Mormon cinema as genre, a helpful entry point is an essay by Mormon film enthusiast Preston Hunter, co-founder of the popular website Ldsfilm.com, followed by two case studies that probe his arguments. I will then turn to two non-Mormon academics: first, film and social theorist Hamid Naficy, to investigate the characteristics that Mormon cinema shares with certain types of ethnic cinemas, and, second, Rick Altman, one of the most influential contemporary film genre theorists today, to examine how Mormon cinema does and does not constitute a genre.

What Is Genre?

The French word genre (pronounced zhan’-ra) entered English around 1770. It comes from the Latin genus (which itself has a Greek root), meaning a kind, sort, style, or class of items; in biology, genus indicates a distinct subgroup, generally containing multiple related species, within a broader family. Genus and its related prefix generate the roots for such English words as generate and genesis (the creation or origination of something uniquely new and distinct); generation (a group of individuals born of the same parent or at the same time); gender (a group of individuals sharing the same sex characteristics); and of course genes and genetics (literally, “pertaining to origins,” which geneticist William Bateson popularized in the early twentieth century to indicate the biological units that endow individuals with their distinctive characteristics). All of these words indicate groups of items that share certain characteristics with each other but differ from items outside the group. This is perhaps the best way to approach genre as well.

In everyday English, genre is used less frequently than its adjectival form generic. Often this word has connotations of low quality, including B-films, store-brand groceries, or cheap medication, but this is not the thrust of its literal meaning, which is simply to pertain to a certain genre, genus, class, group, or kind of related items. Today brands, trademarks, and advertising try to distinguish items from a competitor’s similar products—a point we will return to in discussing Rick Altman—but they nevertheless all belong to the same genre.

With films, even if viewers do not use the term genre, they easily distinguish between westerns, science fiction, comedy, horror, and other categories. The concept is as familiar as the layout of a video store. Grouping films by genre makes them more accessible and also tells consumers what to expect: no bloodbaths at the end of a romantic comedy, for instance. Film scholar Dudley Andrew has pointed out that genre criticism is the blood brother of auteur theory: the first looks at similarities in films of similar content regardless of the director, and the second looks at similarities in films by one director regardless of the content. “Both these methods . . . follow an organized approach and some invariable principles which can be applied to a series of films, one after another,” Andrew says. “But even this is not theory in its pure sense, for its goal is an appreciation of the value of individual works of cinema, not a comprehension of the cinematic capability. We might call [genre and auteur] criticism ‘applied film theory, ‘just as we call engineering ‘applied physical science.'”

Thus, even though a generic study does not deal with film theory proper—in other words, it remains strictly on the taxonomic level—we can still apply a generic analysis to Mormon films in order, as Andrew says, to appreciate their value, both individually and collectively. In turn, I believe this will provide a framework from which to reach increased insight into how cinema—and in particular Mormon cinema—functions.

Preston Hunter and www.ldsfilm.com

Though many Latter-day Saints may not know of Preston Hunter and Thomas Baggaley, since 2000 they have been two of the most influential people in Mormon cinema. As co-webmasters of www.ldsfilm.com, launched not long after the release of God’s Army, they created an online repository for everything related to Mormon film: news articles, information on upcoming productions, box office statistics, biographical material, and other information. As a result, the site is an excellent research aid and a resource in the creation of a Mormon film community. While considering all films relating to Mormonism, Hunter and Baggaley placed special emphasis on theatrical releases made since God’s Army. To cohere and identify these films, Hunter posted a brief essay, “What Is LDS Cinema?,” on April 30, 2001. Slightly amended in February 2005, it has appeared on the site ever since.

It is important to situate this article historically. Hunter was writing immediately after the release of Dutcher’s second theatrical film, Brigham City (2001), and thus was literally the only one writing on Mormon cinema at the time. Since he was attempting the difficult task of writing on the cusp of a new movement, he exhibited wonderful foresight but also an inevitable lack of knowledge about Mormon film’s history, parameters, and future. This fact increases the essay’s historical importance, capturing how one thoughtful observer perceived a new movement at its very beginning. More importantly, Hunter established the vocabulary used on ldsfilm.com; thus far, its definition of Mormon cinema has been generally if implicitly accepted by the larger community without much critical assessment. Without denying the essay’s importance, the time now seems right for such an evaluation.

Hunter begins by praising Dutcher as the first Latter-day Saint to create a feature film about Latter-day Saints. In promoting God’s Army, Dutcher essentially established the parameters of “LDS Cinema” (the term consistently used on the website, often with a capitalized “C”), which Hunter spends the body of the essay investigating. Taking an exclusionary stance, he states that calling it “cinema” immediately excludes anything not released in commercial movie theaters, such as videos, televised films, and official Church productions. Films must also be “made for a wide aspect ratio (‘wide-screen’), not a television set.” He acknowledges the importance of excluded productions—specifically the documentaries of Lee Groberg—but says they “clearly belong in a different category. And it is useful to be able to talk specifically about ‘cinema’ without frequent reference to often incompatible audiovisual media of other types.”

The “LDS” modifier, on the one hand, excludes films made by Mormons but without Mormon content, like Casablanca (1942) and The Land Before Time (1988), and, on the other, films about Mormonism directed by non-Mormons, such as Brigham Young (1940) and Orgazmo (1997). Hunter realizes that a hypothetical film about Mormon scripture would disrupt his unstated definition, however, so he allows that what can be included are, in his quotation marks, “films with overtly Latter-day Saint characters or themes.”

Returning to an exclusionary stance, he appraises the intended audience and rules out anything not marketed primarily or exclusively to Latter-day Saints, such as the irreverent sci-fi spoof Plan 10 from Outer Space (1994). He continues this train of thought into his conclusion, where he implies that LDS cinema must be orthodox: no Mormon villains, for instance. Comparing Mormon films with African American films, he points out that the filmmaker’s orthodoxy is a problem unique to religious cinema, for while either a director is black or not, an ethnic Mormon may not be active in the Church. “. . .A film which was highly offensive to most Latter-day Saints would [not] be recognized as ‘LDS cinema'”—and would not make much money anyhow. Then, to his credit, he wisely leaves the entire essay open to interpretation, commenting that future films “will force re-evaluation of the term. It will be interesting to see what develops.”

Although Hunter never states his definition outright, it may be thus inferred: An LDS film is a feature-length (of at least roughly ninety minutes) fictional film released after God’s Army in main stream commercial cinemas which is marketed specifically and exclusively to Latter-day Saints, is directed by a faithful Latter-day Saint, and favorably depicts faithful Latter-day Saints or characters based in ancient LDS scripture.

Such a definition may describe the heart of Mormon cinema as enthusiasts envision it in the early twenty-first century, but it fails to completely map the terrain. It does not help, for instance, to demarcate a place where Mormon cinema ends. All of Hunter’s criteria are exclusionary except for the single positive characteristic that a film should depict “LDS characters or themes.” This methodology, to define the platonic center of a genre by excluding everything it is not, is very common in genre studies; in fact, it is possibly the preferred methodology for most critics. So this approach is not to Hunter’s discredit, but it does omit a great many films that thoughtful critics—and the writers at Moving Picture World and the Cleveland Ohio News—may want to include.

His first exclusion, of non-theatrical releases, is somewhat troubling for a movement that has produced so much material for video, television, subsidized film distribution (in meetinghouses), and other outlets. His concession to Lee Groberg suggests that Hunter recognizes the problem, but including even one such production would open a Pandora’s box for his definition. Defining “cinema” as referring only to commercial theaters discounts many historical precedents in various national film industries that have had to rely on distribution outlets like agitprop trains, special screenings in civic venues, government subsidies, and video. The vast majority of Mormon-related films—well over 90 percent, by my guess—was designed for similar distribution models, and excluding them would remove the context for the remaining 10 percent.

Hunter has good reason to exclude secular films created by Latter-day Saints, but the cases of Casablanca and The Land Before Time are interesting for their disparity. The former is presumably mentioned because the screenplay passed through the hands of Casey Robinson, a Church member and one of Warner Bros.’ top screen writers at the time. After two other screenwriters had already done a great deal of work in adapting the original play Everybody Comes to Rick’s, Robinson began working on the Ingrid Bergman character and the love story. Simultaneously, two other writers, the Epstein brothers, hashed out the male characters and the war material; a few months later, staff writer Howard Koch was also brought onboard, staying throughout production for rewrites that included changing the entire climax and ending. Robinson, by then well into a successful career, refused to share screen credit, a decision that cost him an Oscar. Also, his limited involvement produced no Mormon characters or themes. In contrast, director Don Bluth’s extensive involvement with The Land Before Time (discussed below) yielded a picture that demonstrates how an ostensibly secular film can indeed contain “overtly Latter-day Saint themes” and be revelatory of the Mormon experience. The wisdom of excluding such films from the corpus is therefore debatable.

Hunter’s next point is that LDS cinema cannot include anything “made,” presumably meaning directed, by non-Mormons. Ironically, his example of director Henry Hathaway’s Brigham Young provides the perfect argument against his point, as Church members—including Heber J. Grant and John A. Widstoe—were extensively involved in its creation. From sympathetic portrayals of lightning-rod issues like polygamy to the use of Mormon hymnody in its score, the film is thoroughly infused with Mormonism. Hunter’s second example is the completely thematically unrelated Orgazmo, an NC-17 picture in which a returned missionary acts in pornographic films to pay for his temple wedding. In analyzing these two productions Hunter says: “But neither Hathaway nor [Orgazmo director Trey] Parker are Latter-day Saints, which seems to be the deciding factor, because both films (and many others made by non-Latter-day Saint filmmakers) predated God’s Army” This sentence requires a small leap of logic, as it is difficult to make the connection between God’s Army’s release date and Henry Hathaway’s religion. There is obviously no causality between the two, and hence Hathaway’s faith is not “the deciding factor.” This slip does, however, tacitly reveal Hunter’s most important criterion: that all LDS films must be released after God’s Army.

Finally there is the issue of the intended audience, a troubling point for all genre studies. As Rick Altman amply demonstrates, most films are marketed as different genres to different potential customers, with broadsides reading, “Action! Comedy! Romance!” Hollywood studios do this because they seek the largest audience possible, and Mormon filmmakers are no different, even if it means marketing to two different groups. Brigham City, for instance, reportedly was packaged in two different cases for its initial DVD release. One, designed for sale in Mormon-oriented outlets, featured head shots of the actors and the tagline, “Nothing attracts a serpent like paradise,” while the other, designed for general retailers, featured blood and much more implied violence. Are half of the Brigham City DVDs Mormon cinema and half not? Similarly, New York Doll’s (2005) video release came in two edits, a family-friendly version and a “mainstream” (i.e., uncut) version with slightly more profanity. Pride and Prejudice (2003) had most of the already scarce Mormon references from its theatrical version excised for DVD.

Not only can marketing and content vary for individual titles, but the entire concept that a genre or ethnic cinema must be marketed exclusively to one group seems invalid. Fiddler on the Roof (1971), a favorite prototype for many Mormon filmmakers, would no longer be considered Jewish cinema by this definition because it was popular with a general audience. The same is true of Schindler’s List (1993), Woody Allen’s films, or any ethnic movie that seeks success beyond the filmmaker’s demographic. In fact, most theatrical Mormon films of the past decade have sought crossover success, which by this definition would exclude them from the Mormon canon as well.

Even if Hunter’s criteria do not entirely withstand scrutiny, his intention—to identify a group of films beginning with God’s Army that share distinctive characteristics in terms of both content and production—is laudable. Films like God’s Army, The Other Side of Heaven (2001), The Singles Ward (2002), The Work and the Glory (2004), and The Errand of Angels (2008) appear to form a historically cohesive group with greater similarities in style and content than differences. They therefore seem to mark the beginning of something like a new wave. Indeed, some of Hunter’s most perplexing omissions are films like the 1977 Brigham, the 1931 Corianton, and the 1915 The Life of Nephi, which otherwise fit all of his stated criteria; they are excluded, however, simply because they predate God’s Army and are not part of Mormon cinema’s modern movement. While there should be accessible terminology for these post-God’s Army films, it is unfortunate that Hunter uses the broad term of “LDS Cinema” for such a small and historically cohesive group, as of 2009 constituting barely one-twentieth of Mormon film history since 1898. The effect is to appropriate the name of an entire movement for its most recent manifestation. If these few theatrical films constitute “LDS cinema,” then what are we to call everything else?

This is perhaps an overly harsh critique of Hunter, who needed to establish a working definition for these films when only two had been released. As the discussion of Rick Altman will show, if questions of Mormon genre are ultimately beyond Hunter’s initial essay, it is because the questions of film genre are often beyond all of us, to a much greater degree than previous generic studies have admitted. Still, Hunter does raise several profound issues about Mormon film that warrant further scrutiny. Perhaps the most important of these is the religious affiliation of production personnel who work on supposedly Mormon films.

Categorizing Mormon Films in Terms of Production

Many discussions of Church-related motion pictures mention whether they are made by Latter-day Saints. In this sense, Mormon cinema resembles ethnic cinemas like Jewish or African American cinema, where the boundaries frequently blur around the edges, particularly when content and authorship are at odds. How does one classify a film about African Americans produced by Jews or Caucasians? Does one include a film by a famous African American director if it features white characters? Such films fall in the liminal space between cultures and hence often have their genricity contested, a pattern that holds true for Mormonism as well. For instance, Wagon Master (1950), directed by John Ford, a Catholic, is arguably one of the most resonant Mormon-themed films in existence, yet it is virtually never included in discussions of Mormon cinema. Religious cinema experiences further complications when the filmmaker’s devotion to the faith changes or is enigmatic or problematic, as with the Catholicism of The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), endorsed by the Vatican but directed by avowed atheist Pier Paolo Pasolini. This issue touches Mormon cinema with the recent work of Richard Dutcher, such as Falling and Evil Angel, made after his public disassociation from the Church.

Even with the possibility for such complex relationships, a simple schema of production personnel’s religiosity can be a useful tool in allowing differentiation within the vast corpus that includes both The Godmakers and God’s Army.

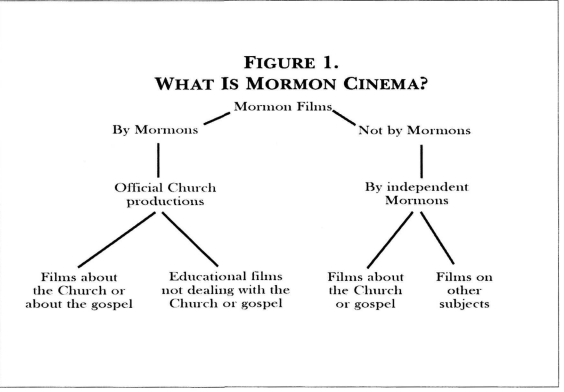

The first two tiers in Figure 1 deal exclusively with who made the films: the institutional Church, Mormons acting independently, or non-Mormons. The final tier addresses content: secular or religious. Demarcating this split is not necessary in an exclusively personnel-based discussion, but it does identify, for instance, how the secular Johnny Lingo qualifies as a Mormon film; any taxonomy that deals with films strictly in terms of the Mormonism of their content would exclude this work, regardless of its historical importance. For this reason, not just to accommodate content-based discussions, understanding personnel is crucial to understanding Mormon cinema, and that includes secular films made by Mormons as well.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1: What Is Mormon Cinema?, see PDF below, p. 28]

One could hardly discuss Jewish cinema without including the “non-Jewish” work of William Wyler, Billy Wilder, Mel Brooks, Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg, and a host of others, and the same is true here: Mormon cinema is very much shaped by the secular work of Neil LaBute, Hal Ashby, Lyman Dayton, Kieth Merrill, T. C.

Christensen, Ryan Little, and others (and not just directors), let alone the hundreds of Church-produced educational productions like Johnny Lingo. But admitting Johnny Lingo, Napoleon Dynamite (2004), and Battlestar Galactica (1978) into the corpus of Mormon films returns us again to some of the issues that Hunter dealt with by excluding such productions. To further assess whether this uniform exclusion is indeed appropriate, we must examine some films that appear to be near the periphery but whose content makes them prime examples of the expression of Mormonism in film.

Looking at Content: How Mormon Is It?

As this cursory analysis of production models reveals, there can be no linear scale of “Mormonness” for a film. Films are complex works that should be evaluated individually, often with unexpected results. A film that initially appears to have nothing to do with the Church might, in fact, be quite thoroughly infused with Mormonism, while one that is apparently full of Mormon content might be rather devoid of it. Disagreement on this issue largely fueled the controversy over States of Grace in 2005. Dutcher’s supporters averred that the film used unconventional situations to explore the Mormon understanding of the Atonement, while his detractors saw it as a worldly film about sex and violence disguised under a Mormon veneer. This disagreement merely shows that the religious content of a film may be different than anticipated and that Mormon material may appear in unexpected places, such as the mainstream cartoons of Mormon director-producer Don Bluth and the 1969 musical western Paint Your Wagon.

Don Bluth

Don Bluth began his animation career at Disney but left in 1979 to found his own studio, finding his greatest success in the 1980s with films like The Secret of NIMH (1982), An American Tail (1986), and The Land Before Time (1988). He has continued working in films, video games, and books up to the present. Many of his films’ narratives, which he helps construct, invite a typological reading in which the events on screen are symbolic of larger mythological or theological patterns. Foremost among these is his use of the hero’s journey, in which the protagonist travels from an initial heavenly union through earthly isolation and back to a more mature heavenly state. In An American Tail, for instance, the young Fievel Mousekewitz is separated from his family en route to their new Zionistic home in the United States. He navigates through a dreary world that tests and tries him, longing to be with his family eternally. Eventually, the family’s Utopian vision is realized when their reunion transforms America into an earthly heaven.

Mormon author Benson Parkinson has identified an even more intricate typology in Bluth’s 1997 film Anastasia, which depicts the surviving Russian princess several years after the fall of the Romanov dynasty. In Paris and not knowing her real identity, Anastasia must strive to remember her past life and reunite herself with her grandmother, overcoming the attempts of the undead Rasputin to assassinate her. Eventually Anastasia and her grandmother recog nize each other by matching amulets. Parkinson says:

Read typologically, Anastasia holds up better . . . than the Disney films. Think of the St. Petersburg palace as a regal, pre-existent, celestial home, mostly-forgotten, towards which we grope, with little more than hope to guide us most the time. We are opposed by a sinister member of the court who has been expelled, and we have to be diligent and pure, and help each other, to overcome the obstacles he puts in our path. We’re given emblems that help us recognize our heavenly parents when we find them, and once we’re united with them we can’t be separated again. Typologically speaking, Disney shows tend to boil down to, “True love (i.e. romantic love) conquers all.” Anastasia boils down to, “If you’re diligent in your quest, you can find your true identity and be sealed to your family eternally.”

How we think of typology depends partly on what we see the author doing. It’s perfectly legitimate to find Christian allegory in Snow White or The Lion King, whether the authors intended it or not, because one view of typology is that these patterns in all the world’s stories are pre-existent—they resonate because we knew them before we came. I think Anastasia is different, both because of Bluth’s LDS background and because he’s explored these same themes in his other films: discovering one’s identity in The Secret of NIMH, and finding one’s family in An American Tail and The Land Before Time. .. . I see Bluth as a Latter-day Saint trying consciously to give these themes a purer expression so they will resonate with people and prepare them for the gospel, or at least help make them truer to their natures.

Parkinson may be more correct than he suspects. In a 1989 Church News interview, Bluth commented, “Everything I do is centered around the gospel. Even our films are, although the secular world would never realize it.”

Bluth made this statement soon after completing The Land Before Time, and this film is perhaps the strongest example of his point. Set in the age of dinosaurs, it tells the story of the young brontosaurus Littlefoot. Initially his herd consists of himself, his mother, and two grandparents. His mother teaches him about the Great Valley, where they must go, before being killed by a Tyrannosaurus rex. Unable to find his grandparents, Littlefoot forms a new herd of orphaned or abandoned herbivore youngsters and begins leading them to the Great Valley. Despite internal dissensions and the continuous threat posed by the prowling Tyrannosaurus, Littlefoot succeeds in leading his friends, after many challenges, safely into the Great Valley, where they are reunited with their families, including Littlefoot’s grandparents.

There are two legitimate ways to read the film typologically. The first posits Littlefoot as a Christ figure: His birth is auspicious—he is described as the herd’s “last hope for the future”—with no physical father present. Later a leaf described as a “tree star” descends upon him like the Holy Ghost at Christ’s baptism. He thereafter becomes a spiritual and literal leader of his people. This typology fails, however, to be completed via a Passion or Atonement process. In fact, it is his friend Petrie who is seemingly resurrected after the climactic battle with the Tyrannosaurus. The second and thus more consistent typology sees Littlefoot as an everyman undertaking a hero’s journey, which is enhanced by his role as a prophet as he guides others to the Edenic Great Valley. Encouraged by visions of his dead mother, Littlefoot is described as the only one who knows the way. Like Anastasia, he overcomes a being like himself but completely infused with evil immediately before finding his way to the valley and reunion with his family. At this point the film’s title seems purposely engineered to give a double meaning to this extra-temporal heavenly state. Here, Littlefoot’s ancient grandparents may represent heavenly parents he vaguely remembers from long ago; the facts that there are a mother and father and that he has retained a veiled memory of them begin to move clearly in the direction of doctrine specific to Mormonism.

There is, however, a third way to interpret the film, one that connects it to the historical Church as well as to Mormon theology. Key to this interpretation is the simple fact that the Great Valley is explicitly to the west, as the caravan is told to follow the shining circle—the sun—day after day over increasingly rough terrain. Thus, their journey becomes a representation of the 1847 pioneer trek: The previously acceptable surroundings in the east are no longer hospitable; the migrants have never seen the valley but believe they will reach it if they obey and persevere, walking every step of the way; the land becomes more arid and mountainous as they proceed; and the Great Valley itself (a simple rechristening of the Great Salt Lake Valley) is fertile but surrounded by deserts and mountains (something, admittedly, historically true in Utah only after irrigation). Littlefoot is both a Joseph Smith—he sees a pillar of light and receives heavenly visitors—and a Brigham Young—he leads his followers across the plains. The film’s closing line of narration even sounds as if it comes from a Church production on the pioneers: “And they all grew up together in the valley, generation upon generation, each passing on to the next the tale of their ancestors’ journey to the valley long ago.”

What Bluth has done, therefore, is to create a typological plan of salvation structure overtly patterned on the trek of the Mormon pioneers, creating a three-way equation between the dinosaurs’ physical journey, the pioneers’ physical journey, and everyman’s spiritual journey. By rooting the narrative in physical, tangible, and relatively recent historical events, the film opens up new meaning on Church history: the pioneer as a type of each of us in mortality. The shadow of the pioneers has been consciously included. Don Bluth’s secular films, then, are part of the religious tradition of the Latter-day Saints.

Paint Your Wagon

Bluth’s insertion of his own faith into his films is not astounding, but Paint Your Wagon (1969, based on the 1951 Broadway musical) is a more surprising achievement. This movie was made with no Mormon involvement and treats Mormons comically, but it is still revelatory of LDS beliefs. Opening in No Name City, California, in 1848— the year between the Mormon pioneer trek and the California gold rush—the film shows how a hen-pecked Mormon man auctions off one of his wives, Elizabeth (Jean Seburg), to Ben Rumson (Lee Marvin), who immediately marries her. She in turn falls in love with his Pardner (Clint Eastwood) and eventually lives consensually with both men outside of town. As the city grows and civilized values encroach, this arrangement is found unsatisfactory. Elizabeth and Pardner evict Ben and pretend to be legitimately married until their desire for feigned monogamy becomes real. Eventually Ben leaves town of his own accord to seek greener, less civilized pastures.

Any discussion of the film’s Mormon content must take into account the genres of the musical and the western. Paint Your Wagon is not the only musical western (or western musical) in history, but it seems to be peculiarly torn between the sensibilities of the two genres in a way that films like Oklahoma (1955) and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) are not. The film features semantic and syntactic elements of both genres but gives precedence to the semantic elements of the western—guns, horses, and cowboys—and the syntax, or events, of the musical—a romantic narrative and even the fact that Elizabeth and Pardner essentially decide to “put on a show.” In essence, the visuals belong to the western while the major plot points belong to the musical; the musical therefore eventually dominates, forcing the western (along with Ben) out of the narrative completely. The rough and tumble frontier town of No Name City is gradually subsumed into a musical milieu, and in the end Pardner and Elizabeth enact the musical syntactic conclusion of the boy getting the girl. Ben rejects this musical world in favor of the western. He literally and symbolically destroys No Name City, making it collapse in on itself as his underfoot mine implodes. Then he disappears, bound for a new frontier. The generic contrast at the conclusion is complicated immensely by the fact that Ben is singing the title song while Pardner and Elizabeth resolve their relationship in a showdown almost as terse as Eastwood’s earlier spaghetti westerns. In these moments, Paint Your Wagon can seem torn apart by its conflicting generic affinities, and Mormonism is caught in the middle.

On the surface, the film’s Mormon influence is minimal and rather inaccurate. Elizabeth’s first husband Jacob is a completely comical figure, caught between two feuding women and complaining under his breath how Brigham Young can handle all his wives but he can’t get along with just two. After Elizabeth’s auction, Mor monism is completely eradicated from her character. This position suggests that Mormonism’s only characteristic is plural marriage and that when Elizabeth loses her Mormon husband she also loses her Mormon identity; true religion is represented later in the film by monogamous Protestant families. Given this quick dismissal of Mor monism, however, it is interesting to realize that the entire body of the film is essentially a meditation on the ethics of polygamy. When Pardner falls in love with Elizabeth, he tells Ben and plans to leave to avoid disrupting their family life. It is Elizabeth who rejects this plan because she loves both men. If “my husband had two wives,” she reasons, “why can’t I have two husbands?” After some thought they all agree that on the frontier—that is, in the world of the western—people can do whatever they like. Polygamy and polyandry are acceptable whenever there are no civilizing structures to dictate otherwise. The logic of this libertarian self-governance is so compelling that marriage ceremonies are dispensed with and Pardner moves in immediately.

Thus in 1969 a Hollywood film apparently accepted and even defended polygamy, the most controversial if antiquated of Mormon beliefs. The film could end at this point with a happy polyandrous resolution were it not that gold is discovered, the city booms, and the urban world of the musical begins encroaching, deftly utilizing the western’s traditional play between frontier and civilization. The family’s home lies outside of town and hence outside the troublesome parson’s influence; but when Protestant families arrive, Elizabeth is forced to provide shelter for one, thus bringing her cottage within the confines of Protestant civilization. From this point on, the western is left behind and with it the compelling frontier logic that had allowed the protagonists to justify plural cohabitation. Elizabeth evicts one of her husbands simply for appearance’s sake. The film’s complete acceptance of Mormon thought thirty minutes earlier proves limited and conditional. It is just a matter of time, now, until the musical wins and plural marriage must disappear entirely.

Ben never fits in the new environment. While the others are becoming civilized, he busies himself corrupting a Protestant youth in the new whorehouse, and thus Pardner becomes the active dramatic character in the film’s final third: He must choose between the dialectic forces of civilized/musical/Protestantism and uncivilized/ western/Mormonism. He picks the former, and he and Elizabeth are described as “a real family after all” and “like a real husband and wife,” implying that, in the musical, polygamous families are in some way false. Now the rejection of Mormonism seems complete, but it is a dissatisfying denouement given the fact, left over from the period of western dominance, that no marriage was ever performed between Pardner and Elizabeth, or for that matter a divorce between her and Ben, let alone with her Mormon husband. Thus, plural marriage remains the driving force behind their de facto union, strongly undercutting the Protestant ending with a lingering sense of polygamy’s validity and importance. Ben’s decision to rediscover his western frontier is sound, given that the No Name City which Pardner and Elizabeth have adopted is not only full of prostitution, greed, and gambling, but has literally just fallen from its foundations, a house built over not just sand but empty air. It is possible at this point to feel that Mormon thoughts and values are more solidly founded than those of “civilization” and that they are afforded a permanent place where Ben is going, where they may not only interact with Protestant notions but even hold their own against them. The frontier—traditionally the place of freedom and opportunity in American mythology—is also the place where Mormonism can thrive. There is some validation of the faith after all.

Paint Your Wagon thus provides a very complicated view of both LDS theology—at least as seen through the prism of polygamy—and film genres. Its complexity does not allow it to endorse or condemn plural marriage. Rather, it creates a space where polygamy can exist as part of a functioning society, dependent on generic norms. Paint Your Wagon, for all its camp, is therefore perhaps the most sophisticated fiction film ever made on American polygamy. Similar examinations could be made of many films and filmmakers, revealing in each case an unforeseen degree of consonance—or dissonance—with Mormon mores and beliefs.

Hamid Naficy and An Accented Cinema

Despite the potential utility of studies such as these, Mormon cinema cannot be treated exclusively as a traditional film genre. Given its nature as a religiously based ethnic cinema, Mormon film also shares many characteristics with traditional ethnic cinemas, but these are highly modified by Mormonism’s condition as a subculture within a larger national context. In examining Mormon film’s ethnic components, it is therefore useful to explore the work of film and cultural scholar Hamid Naficy. Naficy, an Iranian immigrant to the United States, has identified a new type of ethnic filmmaker arguably most akin to Latter-day Saints: exiles and displaced people who are working in a host culture other than their own. Although most Mormons are not geographically exiled, their Mormon ethnic identity is remarkably similar to those exilic cultures discussed by Naficy, as can be seen through two key points. First, all members of the Church have a distinct national and racial identity in addition to their religious identity: they are just as black, white, Jamaican, Afrikaans, Chinese, Bolivian, or Indian as their non-Mormon counterparts. This prompts them to think of themselves as having a multivalent nature, including religious, racial, and national components. Second, Church membership and hence Mormon culture is spread across the globe, from Heber to Hong Kong. This means that all Mormons, in adopting Mormon culture—whether as converts or lifelong members—accept their dualism and find themselves living, in a sense, as a minority in a host culture that both is and is not their own. This dualism is exemplified to a degree by the popular maxim that one should be “in but not of the world.” A globally dispersed culture like Mormonism will manifest itself differently in each national/ethnic culture where it exists. In that sense, comparing Mormonism with diasporic and exilic filmmakers can prove quite profitable.

Hamid Naficy has studied Third World and Iranian cinema as well as theories of exile, displacement, and diaspora and their manifestations in popular culture. His 2001 book, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking examines similarities across a broad range of filmmakers who for various reasons have left their countries and are now working in host cultures. To my knowledge the first Mormon to suggest a connection between Naficy’s accented cinema and Mormon cinema was Heather Bigley, in a paper presented at the University of Toledo in 2004. Bigley offers this cogent summary:

[Naficy] works out qualities of postcolonial alternative cinemas. Careful to remind us that these cinemas are too diverse to categorize as a genre, he divides postcolonial cinema into three groups: Exile, Diaspora, and Ethnic/Identity films. All three worry over the relationship of the main character/filmmaker to the homeland and to the refuge country. Naficy calls them “accented” and then extends that name past postcolonial cinema: “all alternative cinemas are accented, but each is accented in certain specific ways that distinguish it.”

Despite the rather broad group of alternative films this definition may imply, Naficy’s emphasis is decidedly on exilic filmmakers. Their films are generally differentiated from the mainstream in both their artisanal mode of production—using small multitasking crews—and their nonconformist aesthetics. They are often self-aware, autobiographical, or both; and they tend to emphasize issues like personal space, travel, communication, borders, and language. The very term accented, in fact, implies a linguistic precedent. Naficy points out that we all have accents for various reasons, including religion, but the cinema in question here “derives its accent from its artisanal and collective production modes and from the filmmakers’ and audiences’ deterritorialized locations. Consequently, not all accented films are exilic and diasporic, but all exilic and diasporic films are accented.”

As a consequence, Mormon cinema, while accented, shares only certain characteristics with exilic or diasporic cinema. Although Mormons may expect to eventually build Zion in Jackson County, Missouri, they generally do not have a sense of exile like nineteenth-century pioneers or a yearning for what Naficy calls “a homeland yet to come” like modern Palestinians. Because Mormons are so completely subsumed within their national cultures, Mormon cinema most closely resembles Naficy’s category of “postcolonial ethnic and identity filmmakers,” focusing on life “here and now in the country in which the filmmakers reside” rather than life in the homeland, a stance consistent with the modern Mormon emphasis on building Zion wherever Church members live. Consequently, Mormon films lack some important characteristics of much accented cinema such as polyglotism, a focus on geographical and other borders, written text on the screen, and, for that matter, politics.

Mormon culture, however, obviously remains distinct from its national host cultures, retaining unique beliefs and practices and adapting other national norms to fit these beliefs. Because temple worship has no equivalent in most contemporary societies, it is completely unique to Mormonism. Dating and courtship, in contrast, are general phenomena but are modified by Mormons to include provisions against premarital sex and teens dating before the age of sixteen, as well as substituting many culturally specific activities not based on theology or morality (such as, possibly, watching Mormon movies). In the United States, some Latter-day Saints embrace the hyphenated term “Mormon-American,” simultaneously indicating their national affiliation and their resistance to complete homogenization within it; rather, they accept a native discourse that “lies[s] outside ideology and predate[s], or stand[s] apart from, the nation.”

Simultaneously, they also share a “horizontal and multisided [consciousness] involving not only the homeland but also the compatriot communities elsewhere,” Zion throughout the world. There is a sense of fellowship and commonality within the Church despite differences in geography and national culture, and in general Mormons are concerned with how the Church is faring in distant lands. This international interest provides one way in which Mormon cinema proves similar to exilic accented cinemas, despite Mormon film’s tendency to mimic mainstream cinematic aesthetics. This international interest is often quite literal, as Mormon films frequently feature a displaced protagonist either as a pioneer emigrant or, perhaps more commonly, a missionary. Also, like other exilic films, Mormon pictures set in the Church’s pioneer era almost invariably include geographic movement from one place to another. Ironically, however, this migration—which is usually undertaken en masse and not, as in most exilic films, by individuals—is not the central focus of most Mormon movies as it is in pictures like Gregory Nava’s El Norte (1983, about two Guatemalan immigrants trying to enter the United States). Migration, for example, plays a relatively minor role in the Work and the Glory films and even Legacy (1993). In fact, there has only been a handful of fiction films in which migration has actually been the narrative’s key focus: titles like the Church-sponsored All Faces West (1928), the major studio production Brigham Young (1940), and John Linton’s Perilous Journey (1983) and Kels Goodman’s Handcart (2002), both about the 1856 handcart expeditions.

Because missionary films are more common and tend to consistently feature many of the same semantic elements in similar syntaxes, they are sometimes considered the most developed subgenre within Mormon cinema. Missions, unlike pioneer emigrations, are a modern phenomenon with which all Church members are familiar. By definition mission stories trade in culture shock, foreign languages, homesickness, departures, homecomings, and letters—all components of accented cinema. Letter writing, for instance, figures heavily in both The Best Two Years (2004) and The Other Side of Heaven (2001). Letters form a significant preoccupation for the elders in the former and the spine of an otherwise cyclic narrative in the latter. Letters also figure in the plots of other films: a missionary’s written request for advice to his father in A Labor of Love (1990), a Dear John letter in John Lyde’s The Field Is White (2002), and Julie’s letters, or lack of them, to her missionary boyfriend Wally in Saturday’s Warrior (1989). Departures and homecomings also appear in many missionary films, including those just mentioned as well as The RM (2003), Return with Honor (2007), and, most poignantly, States of Grace, although in that case it is the disgraced missionary’s mother who journeys to him.

But in the use of foreign languages, where one might most expect to see components of accented cinema, Mormon cinema circumvents expectations. The majority of missionary films obviates the problem of language by locating the missionary within his own country. Even when the missionary learns a foreign language, many recent films remain in English by either implying that the characters are speaking a foreign tongue when the actors are not—Tongan in The Other Side of Heaven—or contriving the plot so that the characters will continually speak English despite a foreign location—Holland in The Best Two Years. In contrast, accented films often assume a bilingual audience and dispense not only with English but with subtitles, something hardly done at all in Mormon pictures. One excellent exception, however, is the brief use of American Sign Language in Michael Schaertl’s Christmas Mission (1998).

Two non-American Mormon directors living in the United States may have given us the best examples of diasporic Mormon cinema so far. Ryan Little, from Canada, has worked on numerous Mormon and mainstream films, including directing two Mormon themed features, Out of Step (2002), a romantic comedy about a Mormon girl from Utah attending the dance program at New York University, and Saints and Soldiers (2004), about an American Mormon soldier serving in France during World War II. Despite their divergent subject matter, these films are strikingly similar in their use of exilic themes. Both are about characters from the Mormon heartland journeying outside of it. Both emphasize the geographic displacement of their protagonists and how it affects them psychologically, leading to a decrease in mental acuity and preexisting skills Jenny’s dancing and Deacon’s marksmanship. Both characters struggle to communicate their faith and decisions to their peers and companions, and both long for a connection with their distant parents. But Saints and Soldiers goes further than Out of Step: its German is not subtitled, and it is important that Deacon (played by Corbin Allred, the same actor who used ASL in Christmas Mission) is the only bilingual person in the film, having served a mission in Germany. A subtle scene with a French farmwoman is centered entirely around the characters’ desire to communicate across language barriers. The film’s ending also features virtually the only border crossing in Mormon film as the protagonists attempt to cross from German to Allied territory. Finally, Little also functions as his own cinematographer, doubling a production role as is common in the artisanal methods employed in much accented cinema.

Christian Vuissa, from Austria, has consistently devoted more of his output to Mormon films than Little, including founding the LDS Film Festival in 2001 and organizing it every year since. Vuissa’s first feature, Baptists at Our Barbecue (2004), was a disappointing comedy that relied heavily on Hollywood aesthetics. But his earlier short film, Roots and Wings (2002), was much more complex, rewarding, and accented. It featured a Mexican family living in the United States and dealing with the pressures of acculturation: a teenage son who plays basketball and won’t speak Spanish, a brother/uncle who exhorts the father to return to Mexico with him, and the invasion of an American religion—Mormonism—that threatens to subvert their Catholic faith and pull the family apart. Significantly, the script was a semiautobiographical work by Mexican-American Maria Augustina Perez.

Vuissa co-wrote his second feature film, The Errand of Angels (2008), with Heidi Johnson, who similarly created a semiautobiographical script from her mission experiences in Austria, Vuissa’s homeland. Besides the fact that this is the first film to ever feature female Mormon missionaries in the central roles, the most refreshing aspect of the picture is its extended use of German, not only with the natives but among the missionaries themselves. The film uses subtitles, and the American missionaries’ poor language skills have been criticized by some as purposely disrespectful of the quality of fluency achieved by actual missionaries, but the fact that German is used as extensively as it is marks a major milestone in the representation of missionaries on film. This film is also the missionary film most concerned with culture shock and acculturation, rather than proselytizing and the conversion of investigators.

While crossing borders and adjusting to new cultures is not the point of Mormon cinema in its broader sense, we can take the examples of these exilic films and build upon them as we examine all Mormon pictures, including those set right in the heart of modern Utah. Virtually all Mormon films are accented in certain ways other than those explained above, and it is these that, again, help increase our understanding of what Mormon cinema is and how to characterize it as an ethnic or generic cinema. The two most important such characteristics are the films’ incorporation of, first, Mormon language and, second, Mormon values.

Employing a vernacular language without translation for the audience is perhaps the most common and important way for alternative cinemas to express their independence, and Mormon films have excelled at this since their inception. God’s Army was partly seen as revolutionary because it used missionary lingo without explanation, but older BYU films from Judge Whitaker’s tenure (1953-74) likewise did not explain terms like “the elders’ quorum presidency” in When Thou Art Converted (1968), “home teaching” in Worthy to Stand (1969), or even “tithing” in Windows of Heaven (1963). In recent years HaleStorm Entertainment has proven the most adept, if comically, at exploiting Mormon jargon. The best example from HaleStorm’s productions is The RM, which employs an alphabet soup of LDS acronyms and features a pun-intensive restaurant location. The trend continued with other producers. Napoleon Dynamite, made by Latter-day Saints for a general audience, created a nationwide fad with its vocabulary, a heightened and stylized language based in actual Mormon profanity like “gosh,” “heck,” “freakin’,” “retarded,” “sweet,” “dang,” “fat lard,” and the less-common “butt-load.” The Best Two Years bases an entire subplot on one character’s use of the missionary cussword “flip.” When non-Mormon filmmakers get the vocabulary or basic customs wrong, as in Angels in America (2003), September Dawn (2008), or the HBO series Big Love, it is painfully obvious to insiders.

Not incidentally, music may function like language, enhancing authenticity and invoking increased meaning when Mormon tunes are employed. When Max Steiner’s score for Brigham Young quotes “The Spirit of God,” it has much greater resonance for the Mormon viewer than the general viewer because the former is thoroughly familiar with that hymn’s lyrics and history as well as, perhaps, personal experiences in which that hymn was involved with spiritual or emotional manifestations.

On the second point, to say that Mormon films invoke Mormon values may sound quaint, but it is the logical and much more important extension of invoking Mormon language. The worldview of Latter-day Saints is different than that of non-Latter-day Saints, even within the same nationality, race, and economic class. Sharing that worldview makes Mormon films engaging for their audiences, but non-Mormon viewers, who do not understand the “accent,” can react with incomprehension or apathy. As a hypothetical example, a film about a recent convert’s temptation to drink coffee could be gripping to Mormons but inconsequential and boring to others. At its best, when not trying to pander to non-Mormons by watering down its Mormonism, Mormon cinema is full of references to theology, doctrine, scripture, culture, and history that enrich the experience for the culturally literate viewer.

Given that understanding, however, it is still helpful to recognize the diversity that exists within Mormonism. The Singles Ward, for instance, is not a film about Mormonism in general but a specific group, single adults, in a specific location, Utah Valley, thus leaving many of the jokes and references incomprehensible for Church members as close as Idaho, let alone India. The Singles Ward was much criticized for this approach, but such a level of specificity can be beneficial as long as it is not treated as a true synecdoche for the whole of global Mormonism. It is also important to remember that the spiritual components of Mormon culture are fairly universal de spite ethnicity or national host cultures. It is these spiritual characteristics—faith, repentance, family, revelation, and so on—that form the heart of Mormon identity and hence Mormon cinema.

Thus, while Mormon films do not always reflect accented cinema’s emphases on internationality, they generally do reflect a Mormon culture superimposed upon a host national culture. Understanding this duality can help us relate Mormon films to the broader non-Mormon world, cinematic or real.

The final and most important way in which Hamid Naficy’s theories aid an understanding of Mormon cinema, however, is in relating them back to Mormon society, including both the films’ supporters and critics. The result is a much richer comprehension of how Mormon films function within their own social context. As mentioned, Mormon filmmakers are not marginal or subaltern but interstitial, emanating from where dominant and minority groups interact: “To be interstitial .. . is to operate both within and astride the cracks of the system, benefiting from its contradictions, anomalies, and heterogeneity.” This duality affects the thinking of all members of accented communities, not just the filmmakers; thus, most “ethnic communities are highly sensitive to how they are represented by both … outsider and insider filmmakers. They often feel protective and proprietary about their ‘image,’ sometimes even defensive—all of which forces accented filmmakers either to accede to the community’s self-perception and demands or to take an independent path at the expense of alienating the community and losing its support.” Naficy terms this dilemma “accented cinema’s extraordinary burden of representation.”

Richard Dutcher is without doubt Mormonism’s prime example of this dilemma. Indeed, Naficy’s descriptions of Atom Egoyen and other filmmakers could have been written about Dutcher. Like Egoyen, an occasionally controversial Armenian-Canadian director, Dutcher is an artisanal multitasker who has appeared in his films and incorporated autobiographical elements, principally in God’s Army and Falling. Like Ryan Little, Dutcher depicts Mormon community members dealing and communicating with the outside world, whether on missions in God’s Army and States of Grace or by bringing the outside into the cloistered Mormon heartland of Brigham City. In this light, we can see that the negative response of many Latter-day Saints to Dutcher’s work is not dependent so much on the films themselves as on preexisting social issues within the Mormon community. Accented communities exert tremendous pressure on filmmakers to create super-films, containing “all of the best that the ‘original’ or the ‘authentic’ culture is perceived to possess and to rep resent as fully as possible the diaspora community,” a task which is not only impossible but which can lead to films that whitewash the group’s image and become artistically sterile. Despite criticism, Dutcher has eschewed this temptation, creating instead honest films that depict Mormonism with all its intricacies intact.

Those who object to Dutcher’s films seem to do so for one of two reasons: either for portraying the faults of his Mormon characters, as occurred most publicly with the outcry over States of Grace, or, inversely, for depicting priesthood ordinances, a concern that preoccupied most critics of God’s Army. On the surface these criticisms appear diametrically opposed—the one for showing faults and the other for showing spiritually private experiences—but they actually both stem from the same concern over a non-idealized cinematic image. Naficy gives many examples of the first type, such as the response of Indians against Mir a Nair’s India Cabaret (1985) for its exotic female dancing and Salaam Bombay! (1988) for its depiction of poverty. As for depicting ordinances, Naficy examines similar criticisms against showing the traditional Muslim slaughter of a sheep to welcome a new bride in Ghasem Ebrahimian’s The Suitors (1989):

These [negative] reactions … show that the exiles felt betrayed by a director who exposed and signified upon aspects of the native culture from an insider perspective but did so for the benefit of outsider audiences. This is because Ebrahimian violated two norms of Iranian collective identity: maintaining a clear separation between self and other, and loyalty to the insider group. . . . When indigenous practices are both produced and viewed outside their naturalized contexts, they become defamiliarized and may be devalued, particularly if viewers are defensive about those practices. If viewers are not defensive [perhaps Dutcher’s goal], then defamiliarization may produce the promised critical awareness and pedagogical effect that Bertolt Brecht theorized.

This critical awareness has been made available to Dutcher’s viewers. When my brother first saw the scene in God’s Army in which the missionaries bless and heal the cripple Benny, he assumed an ironic and detached attitude at the event’s improbability. But after further introspection, he realized that such a blessing is indeed possible, an effect that might not have occurred had he heard the story in a traditional setting like a Sunday meeting. Precisely because it was presented in the defamiliarizing context of a movie theater, he paid greater attention to it and felt increased faith in priesthood power. Still, accented filmmakers must be careful not to overstretch and offend too much of their target audience—as Dutcher has apparently done with Falling—or, particularly, potential investors for future pictures.

Culturally specific films have a much harder time securing financing and distribution than mainstream films, adding to the appeal of crossing over into the mainstream. After Saints and Soldiers, Ryan Little switched to mainstream films, as have Dutcher, Andrew Black, Kurt Hale, and a host of other Mormon directors. Even Atom Egoyen has become increasingly homogenized into classical norms as his popularity—and budgets—have grown.

I believe that the Mormon accent diffused throughout Mormon film best exemplifies how it can be considered an ethnic cinema, particularly in explaining its reception among Mormons and non-Mormons and how anticipation of that reception can influence filmmakers’ choices. In the context of this cultural setting, Mormon films do, however, exhibit characteristics more traditionally assigned to film genres. Thus, while recognizing Mormon film’s ethnic components, investigating its generic characteristics will lead to a comprehen sive—if evolving—understanding of how Mormon cinema exists in the interstices between a singularly ethnic and generic identity.

Rick Altman

Rick Altman is a well-known film historian and theorist whose specialties include film sound and genre. In 1984 he published the article “A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre” in Cinema Journal in which he proposed a new approach to film genre that reconciled two divergent strains in previous genre theory. Not only has the essay been extensively republished, but its approach has been widely accepted and applied in the ensuing years, including in Airman’s own 1987 book, The American Film Musical. He remained troubled, how

ever, by flaws in his theory and, in 1999, published Film/Genre, a book which revises his original thoughts. Throughout the rest of this article, I will put Mormon film through the same evolutionary process, following Altman’s theories from 1984 to 1999.

“A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre”

In his original essay, Altman begins with a summary of film genre studies up to that point. He posits that these contain three fundamental contradictions, two of which concern us here. The first is that recent genre criticism had taken a structuralist stance, treating genres as neutral constructs in an ahistorical space rather than as evolving phenomena generated by a linguistic community, generally Hollywood, and intended for a specific audience. In other words, they are treated as ahistorical artifacts when they are in fact historically mutable. Second, different people often discuss a single genre in vastly different terms: half take an inclusive stance, often compiling unwieldy lists of every possible film, and half take an exclusive stance, usually written as an essay, that proposes an elite group of films as the fundamental core of a genre. Altman illustrates this discrepancy in an invented dialogue comparing Elvis Presley films with Singin’ in the Rain; Presley, because he sings, must be grudgingly admitted into the corpus, but Singin’ in the Rain is “a real musical.” We have already seen this problem in Mormon cinema: the list of 4,591 films included in the Mormon Literature and Creative Arts Database represents the tautological, all-inclusive approach. In contrast, Preston Hunter’s essay delineates what he sees as the core of Mormon film, not by creating positive inclusive criteria but negative exclusive ones that whittle the genre down to its classical ideal.

How do these divergent positions exist simultaneously? A close look reveals that the first position deals with the semantics of genres, the second with syntax. Semantics in this case means elements nouns—that usually make up a genre’s content, like the guns and horses mentioned earlier as part of westerns. The syntax is the way in which these elements are composed or arranged—the verbs. Guns and horses may also appear in period romances and war films, but when they are arranged in a syntactic narrative structure that uses them in a way distinctive to the frontier—the main street showdown or charging cavalry, for instance—then the film can be called a western. Thus, guns and horses semantically exist in a broad range of films but are used in a specific way only in a narrower syntactic group.

The relationship between semantics and syntax is the area of play where Altman suggests the study of genre be located, thus alleviating the contradictions that had hitherto plagued the field. For example, genres historically may be created by either a stable set of semantic elements being arranged into a new syntax or by an established syntax taking on new semantic elements. Also, the discrepancy between critics who create broad tautological lists and those who focus on an elite corpus of highly similar texts would diminish as they both investigate what genres consist of and how these elements are arranged at both the center and the margins.

Applying this theoretical model to Mormon-themed films quickly shows that they cannot be considered a single genre, for the semantic and syntactic elements are too broadly drawn and too sparsely shared. Some semantic elements include temples, pioneers, missionaries, baptisms, covered wagons, handcarts, sacrament meetings, prayer, testimonies, meetinghouses, scriptures, family home evenings, and priesthood leaders—in other words, elements of Mormon history and culture. Arranging them syntactically, however, is problematic, as no body of films has used enough of them similarly enough to establish consistent patterns. This is true despite the fact that a few films share a handful of syntactic elements, such as a character repenting or undergoing conversion. Even if we examine just one semantic element, such as priesthood leaders, its syntactical placement from film to film varies significantly; note for example the difference between Jared as the elders’ quorum president in The RM and Wes as the bishop in Brigham City, or the difference be tween the home teachers of The Home Teachers (2004) and Worthy to Stand. If we recognize that the most common semantic element is Mormon characters, then we quickly see that the range of their syntactic use renders discussion useless. No single definition can aptly summarize all Mormon films.

[Editor’s Note: for Figure 2: What Is Mormon Cinema?, see PDF below, p. 47]

There are, however, similarities among smaller groupings of films. Two pictures like Legacy and Saturday’s Warrior could not seem farther apart, yet both feature a romance between a young woman and a man converted by a missionary she knew beforehand, the rebellion of the oldest son against his father’s faith, the rebellious son’s return, and cultural conflicts between Latter-day Saints and the society around them, personified in street gangs/mobs. Furthermore, in God’s Army, The Other Side of Heaven, The Best Two Years, and States of Grace, mission presidents reprove and encourage missionaries, a semantic element used in a specific syntactic manner. Similar examples proliferate throughout Mormon film, allowing us to create a taxonomy of potential genres and subgenres within the larger corpus of Mormon cinema.

In suggesting these schemata, I am including only films in which Mormon elements play a major role, excluding the Church’s educational films and films that include only passing reference to Mormonism. Also, I am not specifically including nonfiction films, although many will fall within the same categories. (See Figure 2.)

The boundaries between these categories are plastic and permeable. Because they are also fairly self-explanatory, rather than list pertinent titles for each I would like to mention a few points illustrating how these schemata relate to Altman’s original thesis.

The first division, between traditional and instructional narratives, is based upon a syntactic difference. The Church has produced many films for classroom and training purposes that subvert traditional narrative structures by pausing the film for class discussion, inserting portions of general conference sermons or other direct address, or inserting diagrams or other instructional materials. Otherwise, such films retain all of the semantic elements expected in Mormon films.

Films with traditional narratives can perhaps most easily be divided by their historical setting, whether in this or in past dispensations or eras. Those in the latter category are essentially set in the context of ancient scripture like the Bible and Book of Mormon. Of these, some adhere faithfully to ancient texts, including essentially every film to depict Jesus Christ, while others take narrative liberties. The Testaments of One Fold and One Shepherd (2000) embodies this

division as its scenes from the Bible adhere strictly to the scriptures and even classical painting (primarily by Carl Bloch) while all the material set in America is completely invented. A similar dichotomy can be seen in the Living Scriptures cartoons of the New Testament from the 1990s, where much dialogue and action are invented for other characters, including those in the parables, but virtually never for Jesus himself.

Many films set in the present era feature traditional Mormon semantics but not always in ways favorable toward the Church. Anti-Mormon films like A Victim of the Mormons and Latter Days (2003) have many of the same elements as pro-Mormon films but deploy them in remarkably different syntaxes, such as, in Latter Days, a missionary finding liberation in accepting his homosexuality. With both negative and positive films on Mormonism, it is interesting to note that, with very few exceptions such as The Other Side of Heaven, they are either set in the present or before 1900; if more films were set in the early twentieth century then a new division would be in order. Pioneer-era films can either cover the Church’s whole nineteenth-century history, as with Legacy, or focus on only one specific historical period, such as that of frontier Utah. Films with these settings often exhibit syntactic affinities with films set in the present (e.g., repentance or romance); but as period pieces, their semantic elements are remarkably different.

I have divided modern films into four categories, though there could be more. At this stage, many of the semantic elements, the physical trappings of modern Mormon culture, are shared. The divisions are thus based upon semantic emphases: a character’s repentance, conversion, or spiritual epiphany; a traditional romance; achieving a goal not directly related to religion; or executing a Church calling. Repentance films can center on any type of spiritual awakening and often overlap with another plot such as a romance or mission service.

I have further subdivided romantic comedies depending on whether both characters, or only one, are active Latter-day Saints, with a further division for films where the love interest is inactive or non-Mormon (as in Charly, 2002) or the protagonist is (The Singles Ward). Likewise, “nonreligious quest films” refers to pictures that feature Mormon characters who are pursuing traditional secular goals, such as solving the murders in Brigham City or becoming rock stars in Sons of Provo (2005).

Films about Church callings can also be subdivided into several categories. Because of the disproportionate number of films dealing with missionary work, I have made them a separate category, subdivided by whether the protagonist is the missionary (The Errand of Angels) or the investigator (Roots and Wings). The majority, though not all, of films dealing with other Church callings have been produced by the Church itself to inspire members to greater service; most of these were commissioned by the Sunday School or other auxiliary organizations in the decades when they held their own annual conferences. Examples include Teacher, Do You Love Met (1986), No Greater Call (1967), Continue to Minister (1988), It’s the Ward Teachers (1956), and so on. A significant subset of these films, which I have called “brother’s keeper films,” depicts those who, acting in their callings, reach out to someone who has strayed or is in spiritual peril, as in What About Thad? (1968), That Which Was Lost (1969), Come Back, My Son (1954), and of course My Brother’s Keeper (1961).

This taxonomy is obviously imperfect and incomplete—many other potential categories could be added—but I hope it can help stimulate discussion of specific patterns within Mormon cinema. It is easier to discuss the semantic and syntactic similarities of films that focus on fulfilling callings or pioneers gathering to Utah than for Mormon cinema as a whole. It also provides a springboard for comparisons among groups. We can now examine how a semantic element like the temple is handled differently in the modern romance Charly than in a period piece like The Mountain of the Lord (1993). Such comparisons can help us identify and negotiate the interstices between apparently unrelated films and thus better understand the general unity among all Mormon movies.

Film/Genre: A Semantic/Syntactic/Pragmatic Approach

The most prominent flaw with the preceding taxonomy is that it still treats Mormon films as ahistorical entities, forever static and defined. Altman himself sensed that limiting discussion to semantics and syntax ultimately did not solve this problem, prompting him to return to the issue with a much more thorough and historically based analysis in his Film/Genre. In order to properly evaluate film genre, he examines the history and conception of genre itself, including predecessors of cinema such as literature and painting, before moving into a pragmatic analysis of how film genres follow similar patterns.

Since Aristotle, there has been very little agreement about what genre actually means. Altman points out that “the term inconsistently refers to distinctions derived from a wide variety of differences among texts: type of presentation (epic/lyric/dramatic), relation to reality (fiction versus non-fiction), historical kind (comedy/tragedy/tragicomedy), level of style (novel versus romance), or content paradigm (sentimental novel/historical novel/adventure novel).” Essentially the only point of agreement is that genres exist, generally as stable a priori entities, and that critics are independent of them. Not only does Altman now dispute both claims, but he also asserts that the descriptive criteria used to separate genres (form, source, content, etc.) often render discussion futile.