Articles/Essays – Volume 40, No. 4

“The Other” in the Limelight: One Perspective on the Publicity Surrounding the New LDS Temple in Finland

Media attention is a two-edged sword with the potential for both positive and negative publicity. Still, many societal actors find it important to stay in people’s minds through media exposure. Religious movements, for example, often want their share of attention in order to shape public attitudes and attract converts.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is no exception. In the United States in recent years, the Mormon Church has been given the broadest exposure through events not directly related to it, such as the candidacy of presidential hopeful Mitt Romney. The Mormons and their faith also had worldwide coverage during the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics. Furthermore, the Latter-day Saints tend to surface in mainstream media through their missionaries, humanitarian projects, and sometimes features perceived as peculiar.

At the local level, new Latter-day Saint temples are probably one of the largest single sources of media attention. The stated purpose of temple building is, of course, to give devout Mormons easier access to their most sacred religious ceremonies. Nevertheless, these building projects are always accompanied by media attention as a highly welcome side dish, especially during the public open houses that are organized before the completed temple is dedicated. Thus, while the Church spares few means to make the temple construction project itself successful, it also expends great efforts to make the public open house a success in terms of public relations. With temple open houses as interesting intersections between the esoteric and the exoteric, the Church also takes great care to train temple tour guides (usually local Latter-day Saints) and to give an understandable picture of its sacred and partly secret temple tradition to the public.

According to Jan Shipps, interested observers have of late been able to witness a “templization” of Mormonism.[1] While this means, among other things, an increased focus of Mormon discourse and religious practice on the faith’s temples, templization can also be seen in the accelerated pace with which Latter-day Saint temples are being built around the world. During five-year periods from 1987 to the present, the number of new temples dedicated has been four, five, fifty-eight, and seventeen, respectively.[2]

The result of this proliferation is that public open houses at temples occur much more frequently than they did a couple of decades ago. Thus, the general public is more frequently exposed in its own locale to Mormonism, often a foreign faith phenomenon. Considering how frequently open houses currently occur and how important a role they play in introducing individuals to Mormonism (and, not least, in shaping the Latter-day Saint image through the media), research literature on the topic is surprisingly silent.

The purpose of this article is to begin filling that gap by discussing some of the publicity accompanying the recently built Helsinki Finland Temple, located in the southern Finland city of Espoo. Discussions of the public open house among Latter-day Saints in Finland have understandably tended to emphasize positive feedback from the general public. After years of rejection and difficulties, many saw the great interest of the public as something miraculous. In order not to skew the overall picture, however, it is important to also discuss the wider variety of thoughts Finnish people had concerning Mormons and their temple. While many visitors had highly positive things to say, most Finns did not visit the temple, nor was every visitor’s experience positive.

This article represents one attempt to nuance the picture by focusing on Mormons as the cultural or religious “other” in media stories related to the Helsinki Temple building project. The analyzed discourses can be roughly divided into an otherness-promoting hegemonic discourse and into a counter-discourse that seeks to remove the Mormon image of otherness. By otherness-promoting discourses, I refer to modes or manners of speaking that seek to construct an image of something as foreign, as not belonging to one’s own group, “not us,” as simply “the other.” By counter-discourses or otherness-diminishing discourses, I refer to those modes or manners of speaking that seek to eliminate mental images of “the other” and to construct an image of familiarity, normalcy, and something related to and part of “us.”

My material consists of more than 100 newspaper and magazine clippings, radio stories, and television news reports from around Finland.[3] The greatest interest in the temple project was naturally displayed in the media of the capital city region around Helsinki. However, bulletins by the Finnish News Agency or other writings on the Mormons were published in general newspapers around Finland and in professional, religious, and other magazines or periodicals.[4] Chronologically, the material begins in May 2001 when the location of the projected temple was announced and ends in December 2006. It is most abundant for the fall season of 2006. As a general observation, the spectrum of Finnish media where information about the temple appeared is fairly wide geographically and especially wide ideologically.[5] Billing it as “Finland’s first Mormon temple” also naturally aroused interest outside the capital city region.

The context of the publicity is a culture in which a stereotypical and passive Lutheranism is thought of as the most characteristic form of religiousness. Lutheranism often forms the base against which all other religiousness is evaluated.[6] In the case of foreign religions, the media have often concentrated on what is appropriate in Finnish society.[7] My discussion is thus theoretically anchored to the religious and cultural identity of Finns and to the power of the media to maintain boundaries between “us” and “them”—in this case, between average Finnish religiosity and Mormonism.

I will first discuss ways in which the foreign image of the Mormons was brought up by the general media, the religious media, and ecclesiastical representatives of other churches in Finland. Second, I will discuss how Finnish Latter-day Saints sought to diminish or remove images of themselves as “the other.” The subheadings in this article are actual quotations from the publicity and exemplify the themes and attendant discourses. Due to the mass of material, I will limit my discussion and perspective to only a few recurring main themes. One should thus keep in mind that this article is not a general overview of the publicity related to the new Helsinki Temple. Rather, it discusses the publicity from a very specific perspective.

Before engaging with the material, however, I will first build a context by describing the Finnish religious landscape and Mormonism’s place in it, discuss the Helsinki Temple project and open house, and evaluate the role of the media in discussions of phenomena perceived as foreign by the cultural mainstream.

Religion and the Mormon Church in Finland

Finland is a country with 5.2 million inhabitants. About 80 percent are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. According to some sociologists of religion, however, the situation can most aptly be described as the Finns believing in belonging to rather than believing in the tenets of the Lutheran Church.[8] One must also keep in mind that only a fraction of Finns who are Lutherans are active churchgoers. In general, Finland can be said to be a highly secularized country, where membership in the Lutheran Church is more a sign of cultural belonging than a mark of religiosity.

In addition to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland and the Finnish Orthodox Church (comparatively small), both of which hold the status of state church, several smaller churches and religious movements operate in Finland. These can be roughly divided into older Christian or Christian-based churches, the religious traditions of immigrants, and new religious movements. Studies show that Finns often have reserved feelings toward religions that deviate from the mainstream.[9] Although the reasons for these feelings have not been studied in depth, I surmise that the negativity is a reaction to proselytism, popularized images of brainwashing, and the culturally foreign.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been present in Finland in one way or another ever since the first missionaries entered the country in 1875. The country was first dedicated for the preaching of the Latter-day Saint gospel in 1903, with a rededication following in 1946. Since that year, missionary work has continued without interruption. According to the Church’s own statistics, there are currently approximately 4,500 Mormons in Finland, assembling in thirty congregations around the country. LDS meetinghouses have been constructed since the 1950s. Approximately half of the membership is “active” by Latter-day Saint standards, meaning that they attend at least one religious service per month. The Church is ecclesiastically divided into the Helsinki and Tampere stakes in the south while the Finland Helsinki Mission’s districts cover the rest of the country.

Finnish Mormons have often been described as very dedicated temple attendees. They have regularly organized temple excursions since the dedication of the Bern Switzerland Temple in 1955 and, since 1985, to the temple near Stockholm, Sweden. With a temple now completed in their own country, Finnish Mormons have entered an interesting new era, the effects of which remain to be seen.

In spite of the relative normalcy of individual Finnish members who compare well to the general Finnish population, the Mormon Church in Finland has never shaken off its foreign image. Finns are accustomed to religion that is historically tied to Finland and led by their own countrymen. The Mormon Church, in contrast, is transnational but strongly American. LDS leaders who visit Finland are usually American. Mormon missionaries working in Finland are mostly Americans who speak Finnish with clearly perceptible accents and very limited vocabularies. In the past, these American missionaries have even been suspected by some of being spies for the U.S. government.[10] Compared to Lutheranism, the Mormon Church is conservative in biblical interpretation, sexual ethics, and its male-only priesthood. In addition to its non-Finnish features, then, the image of the Church’s otherness in contemporary Finnish society is strengthened by the values it espouses.

The foreign image is, of course, not unique to Mormonism in Finland. Mormonism fights an identity of otherness and foreignness in all new host cultures into which it spreads. To conquer these difficulties, Latter-day Saints would have to arrive at unique acculturation solutions in each country. So far, however, the operating model has emphasized the international unity (and, by extension, the American nature) of the Church. Policies and operating models are formed in the United States and spread worldwide to other countries and cultures through a hierarchical leadership and organizational structure. Thus, it may be said that the Mormon Church, when detached from its culture of origin, operates to some extent as a colony; the organizational model, methods of action, and Church culture are American-influenced, and there is relatively little leeway for cultural adaptation.[11]

Attitudes toward Mormon otherness are ambivalent among the general population in Finland: some want to draw strong boundaries, while others champion religious pluralism. Globalization and immigration have increased Finnish tolerance for and understanding of other cultures, even though these processes have not removed the traditional feelings of foreignness and otherness. It is clear, for example, that membership in the Mormon Church is not thought of as normative Finnish religiousness. Rather it is something foreign that creates an identity of otherness.

Mormons themselves generally seek to remove boundaries. Undoubtedly, their purposes vary from promoting mutual respect to creating cultural continuity in Christian host cultures and thus lowering the threshold of conversion.[12] In this, the Mormons are not alone; most churches that seek to increase their membership numbers and their influence in society court acceptance by the mainstream to various degrees. Some sociologists of religion speak of a search for optimum tension. A church has to be sufficiently different from the mainstream to be an attractive alternative. On the other hand it cannot be too different, as that would lead to the church’s societal marginalization.[13]

The New Temple in Finland

New buildings have great symbolic power because they change the existing physical landscape. They serve as landmarks and visible reminders of changes in a country’s culture. People sometimes voice objections to building projects if they find them unsuitable for one reason or another. Examples of this are the “not in my backyard” objections encountered by the building projects of foreign religions. In the southern city of Turku, Finland, for example, some people have objected to the construction of an Islamic cultural center with its minarets.[14] Difficulties with mosque-building projects have been reported also in Sweden, a country similar to Finland in many respects.[15]

The southern cities of Helsinki and Vantaa responded unenthusiastically to the prospect of a Mormon temple for reasons that have not been made public. However, a building site was eventually found in the neighboring city of Espoo, where assistant city manager Olavi Louko voiced his own feelings that Mormonism was a foreign religion, explaining to a newspaper reporter that “Espoo had just included multiculturality and tolerance in its values. I thought that values must be lived by and promised to find a site.”[16]

The Helsinki Temple was completed in the fall of 2006, about six and a half years after the temple project was announced.[17] An open house was scheduled for September 21 through October 7, 2006,[18] with local Latter-day Saints serving as guides. The temple tour consisted of a short introductory video in the nearby accommodation building, a walk through the temple itself, and refreshments and possible further individual discussions after the tour in a tent outside the temple. Depending on the number of people and the length of queues at the temple site, the tour lasted anywhere from about one to three hours. The temple was open from 10 A.M. to 9 P.M., with the evening hours often extended to 10 P.M. to accommodate those who had been waiting.

A press conference was held on September 19, 2006, during which both local and American LDS officials spoke. The conference and the temple tours for the media that followed resulted in television and newspaper stories across Finland, which in turn attracted visitors. In addition to small pass-along invitation cards, the Church also prepared an eight-page advertisement in tabloid form, financed largely by local Latter-day Saints. It was distributed professionally to homes in the Helsinki region and, to a lesser extent, by local congregations elsewhere in Finland. Three weeks after the open house had begun, a total of 55,791 visits to the temple open house had been logged. Some of these visitors were, of course, local Mormons and repeat visitors from Finland and other countries in the temple district. Still, a very large number, mostly Finns, visited the temple of a religion often thought of as foreign and as “the other” on the Finnish religious landscape.

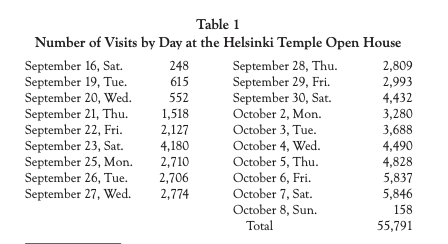

The high number of visitors is, in fact, an interesting and to some extent a puzzling phenomenon, because recent studies show that the Latter-day Saints do not have a good public image in Finland. A poll from 2003 shows that 57 percent of Finns had a negative attitude toward the Latter-day Saints.[19] The figure is 40 percent for the fifteen-to-twenty-nine-year-olds who were interviewed for the 2006 Youth Barometer.[20] In view of the Church’s own goal of 25,000–30,000 visitors, from the numbers alone, the open house was a resounding success. (See Table 1 for a daily breakdown of visitors.)

The Media’s Role in the Discussion of Otherness

In discussing the media’s presentation of “the other,” the media themselves cannot be thought of as the primary source for discrimination or images of otherness. Instead the media reflect attitudes already present in the mainstream of society. The real origin of otherness must be sought in other social processes.[21]

Table 1: Number of Visits by Day at the Helsinki Temple Open House

| September 16, Sat. | 248 | September 28, Thu. | 2,809 |

| September 19, Tue. | 615 | September 29, Fri. | 2,993 |

| September 20, Wed. | 552 | September 30, Sat. | 4,432 |

| September 21, Thu. | 1,518 | October 2, Mon. | 3,280 |

| September 22, Fri. | 2,127 | October 3, Tue. | 3,688 |

| September 23, Sat. | 4,180 | October 4, Wed. | 4,490 |

| September 25, Mon. | 2,710 | October 5, Thu. | 4,828 |

| September 26, Tue. | 2,706 | October 6, Fri. | 5,837 |

| September 27, Wed. | 2,774 | October 7, Sat. | 5,846 |

| October 8, Sun. | 158 | ||

| Total | 55,791 |

However, there is a sort of symbiotic relationship between concepts of otherness and the media, a relationship in which one feeds the other. The media affect individual attitudes and may thus promote an image of various minorities as groups that are foreign to the culture. The media also have a primary position as an actor that articulates the host culture’s relationship to “the other.”[22] Moreover, the religious media in particular interpret and evaluate current events from the perspective of a certain religious worldview.

The media are usually thought of as an objective news producer and thus become crucial when reporting on minorities, since they often function as the majority’s primary contact with the minority. If the image they construct is distorted, the actual reality of a minority group remains inaccessible except to individuals who have special knowledge of it through, for example, an acquaintance who is a member of it. In short, the media occupy a responsible position, as the information they transmit strongly impacts the construction of the minority’s public image.[23]

The role of the media is especially problematized in the case of churches and religious movements. While the media should provide a neutral and objective look, religious movements often seek to mediate a growth-promoting image of themselves. This characteristic, of course, also holds true for any non-religious group with a special interest or bias to promote. In such cases, the media must tread carefully to avoid stereotypical views and to give correct information based on credible sources. At the same time, the media should not function as a critiqueless propagator of the interests of either minority groups or their antagonists.

Achieving a balance can be difficult, and reporting on minority faiths has often been negative, even to the extent that a negative public image can become part of a religious movement’s identity.[24] This is probably true to some extent in the case of the Latter-day Saints in Finland. After the public open house at the Helsinki Temple, for example, the official Church News, a special weekly section of the Church-owned Deseret News, stated in a somewhat black-and-white manner that Finnish media had been the Church’s “long-time detractors” but that things had now changed.[25] Actually, however, Finnish media had already earlier balanced negative descriptions with neutral and positive information on the Latter-day Saints.

Even with good intentions, the media often produce discourses that follow the perspective of the mainstream population. This can occur, for example, due to the private feelings and thoughts of the reporters themselves. Hence, discourses about the Mormons often show features that deviate from average Finnish culture. Furthermore, media reporting can construct an image that creates differences between society’s majority and minority, between “us” and “them.”[26] For example, when Finnish media describe “the Mormon way of life,” it is hard to imagine that they would similarly employ such a blanket generalization in speaking of “the Lutheran way of life.” That way of life is thought of as part of the mainstream’s attributes, and it is therefore not necessary to speak of it in the same way.

Although journalists strive to be fair, their manner of speech can easily promote a foreign image of various groups. Smaller churches may be called religious “communities” or “societies,” while the Evangelical Lutheran Church is often merely called “the Church.” In this kind of discourse, the Lutheran Church becomes familiar and safe, while other churches and movements are something out of the ordinary. In some cases, a sinister label can be implicitly attached to smaller churches. For example, when reporting on the recent suicide of a religious person, a journalist wrote that “no particular denomination or sect was found” behind the matter. Instead the believers accused of aiding the now-deceased person to commit suicide had become acquainted with her in “a completely regular Lutheran Bible circle.”[27]

As a simplified summary, then, it can be said that the choice of topics and words by the media affects the image of familiarity or foreignness attached to churches and religions. At the same time, it must be remembered that the point of analyzing discourses is not to criticize individual reporters; they function within the larger discourses of society and may thus maintain images of otherness without noticing it themselves.[28]

A few clarifying words on the media specifically in Finland are appropriate to contextualize the following discussion. The television media in Finland consist mostly of a handful of nationwide channels and a larger number of small regional channels which, in general, are less popular than the nationwide channels. The radio media similarly consist of a handful of nationwide stations with both nationwide and local broadcasts and a fairly large number of local stations. The print media consist of three truly nationwide newspapers, some larger regional newspapers, a multitude of smaller local papers, and a wide variety of secular and spiritual newspapers, magazines, and periodicals. Material for the news media is distributed nationwide by the Finnish News Agency (Suomen Tietotoimisto, STT) and is often printed in the same form in newspapers around the country. In addition to this source of news, every news outlet also creates its own stories in normal fashion. (See Appendices 1–2.)

The General Media: “The Feeling Is Different Than in Churches Usually”

The purpose of this section is to illustrate Mormon-related discourses of othering in the general media. While these media are aimed at the general Finnish population, even Finns who are not actively religious are likely to be members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland and therefore likely to accept it as an element of the national identity of Finland. As sample themes, I have chosen the special nature of the Helsinki Temple as a construction site, the temple as a closed place of worship, the American image of the Mormon Church, and distancing reactions to the religious ceremonies performed in Mormon temples.

“The Week’s Special: The Mormon Church’s New Sanctuary”

Temples are especially sacred to Latter-day Saints. Whereas weekly worship services are held in ward and branch buildings, temples can be interpreted as sites of pilgrimage that are visited less often. The sacredness of the temple can be seen in, among other things, the special arrangements at the construction site and the entry requirements of a completed temple. Both of these issues received attention from the Finnish media.

On the construction site, the Mormon Church instructed its contractors not to smoke, swear, or listen to the radio. Moreover, the press juxtaposed this unusual site with regular worksite conditions by commenting that “not even a girlie calendar hangs on the walls of work site booths.”[29] The quality requirements for the work were extremely high, and the site was lauded widely as a place of high quality where professionals could utilize the full range of their skills and do their jobs properly.[30]

In contrast to Lutheran churches, Mormon temples are closed places of worship. According to a Finnish LDS public affairs representative, the temple is “isolated from the world and a protected space. Only the worthy may enter.”[31] Many newspapers emphasized the significance of the open house in contrast to its future inaccessibility: “This building is not open for everyone,”[32] and after the open house, “the temple will be dedicated, and those not of the religion have no business in the temple after that.”[33]

People in Finland are used to seeing the symbol of the cross associated with buildings of Christian churches. The cross is perhaps the most important symbol creating unity among the Christian ingroup. Latter-day Saints do not use it, however. Some media outlets noticed this omission: “There is something like a Church tower seen on top of the trees [as you approach], but there is a golden angel on the top.”[34] The comment shows the surprise concerning this element. The ban on photography inside the temple also differs from many other religious buildings and was a regular comment in articles about the temple.

Finnish churches often contain a large hall where the congregation gathers. When looked at from the outside, Mormon temples give the impression of containing such a spacious assembly room instead of the numerous smaller rooms they actually contain. One reporter in the capital city region commented: “By the way, the temple doesn’t, to the surprise of many, have any large undivided hall space like our churches do, Lutheran churches and others.”[35] The innocuous contrast between “our churches” and the Mormon temple implicitly labels the temple as part of “the other.”

“Light for the People in the American Way”

While it may be quite difficult to exactly and objectively define the essential differences between American and Finnish culture, many reporters thought they saw Americanisms as they visited the open house. The practical arrangements of the temple open house were taken care of by Finnish Mormons. The general instructions, however, came through supervision from Church headquarters—in effect, from Americans, and perhaps were thus culturally slanted.

Some reporters thought the temple felt American due to its architecture and its furnishings. One journalist noticed artificial flowers and even pondered in a lighter mood, based on the general impression, whether the teeth of the visitors were possibly whitened,[36] whereas a radio reporter noticed the “American [interior], . . . deep carpets and shiny thick panels, light and space like . . . in Hollywood props.”[37] The totality was, in one writer’s opinion, “undeniably ‘American’ and has little in common with cool Nordic or austere Finnish design.”[38] As another writer put it, “There is just something too American in it, even if most of the building work is Finnish.”[39] Indeed, a reporter thought the Mormons were now offering “light for the people in the American way.”[40]

Many open house visitors met—especially on the day of the press conference—foreign Mormon leaders and missionaries in addition to Finnish temple tour guides. The reporter of a nationwide tabloid newspaper wrote that he was greeted in English as soon as he entered the temple site, and “along a strip of 20 meters I meet at least three young men speaking broad American English.” In addition, he wrote, a “slew of American brothers” presented “in the beyond-the-puddle style what felt like an unending amount of thank yous.”[41] The experience implicitly mediates a message depicting Mormonism as a foreign phenomenon. This foreign image was strengthened by a news feature shown on nationwide television, which included an American Mormon leader’s comments in English.[42]

A radio reporter in the capital city region commented on his positive experience among the visiting crowd by saying that “the Americans are splendidly competent at handling large crowds punctually and efficiently. . . . [The crowd] is kept in control very well, and the atmosphere is upheld in a really professional manner.”[43] The comment is interesting, considering that Finnish Mormons handled the local arrangements. Does the comment represent the reporter’s subjective assessment, preconceived notions, arrangements that really deviated from Finnish norms, or something else?

“A Foreign Sect Enters Finns’ Forefathers into Its Baptismal Registers”

Latter-day Saint temple ceremonies are esoteric and Mormons do not normally speak of them in public in a detailed manner. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, the practice of proxy baptism in particular generated negative feelings in some of the general print media, mostly during the spring of 2004 and usually in the more popular media rather than traditional “quality” papers.

An article in a nationwide tabloid newspaper was headlined “The Deceased Will Soon be Baptized Here” and stated among other things that Adolf Hitler had received Mormon proxy baptism.[44] A regional newspaper stated shortly thereafter in a small piece on its front page that the “baptism of the deceased” and other proxy ceremonies that Hitler had received were “hair-raising rituals.”[45] A column in a newspaper distributed free, mainly in the capital city region around Helsinki, was headlined “Baptized against One’s Will.” The writer thought that “the fact that the sect has already married Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun by proxy should ring the warning bells.”[46] A nationwide magazine article reinforced the image of Mormonism as a foreign and strange religion by stating that “the American Mormon Church is going to baptize into its own faith the forefathers of the Finns.”[47] The writer, identifying former Finnish president Urho Kekkonen as an icon of the nation, stated that a proxy baptism had been performed for him, too.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Latter-day Saints financed microfilming parish registers of the Lutheran Church in Finland.[48] While the Church advises its members to perform proxy ceremonies in behalf of their own ancestors, such ceremonies have also been performed without regard for kinship relationships through Church-sponsored “name extraction” programs. Some Finns have voiced their disappointment and their irritation that their Lutheran forebears have received Mormon proxy baptisms. Said one: “My forefathers have been members of the Lutheran Church as far back as parish registers are available. It is therefore very insulting that Mormons in their temple rites use the names of my ancestors.”[49]

The juxtaposition of Finnish forefathers and foreign Mormons has been strengthened by stating that many people find “detestable the thought that a foreign sect is entering their forefathers into its own baptismal registers” and that “the sect” in so doing forgets the will of the deceased.[50] The Finnish Data Protection Ombudsman stated that it is a surprise for many Finns “that the information of their relatives is in the Mormons’ books.”[51] A former Mormon stated that she had gotten upset about the doctrine of proxy baptism a number of years ago and that the Lutheran Church “awoke to the newcomer too late” to prevent the construction of the temple near Helsinki.[52]

In summary, some see proxy baptisms as a practice offensive to Finnish customs and even as dishonoring the deceased. Such an emotion-invoking discourse can be seen as a strong reinforcement of images of otherness. Its main message seems to be that “Mormon activity is not within the bounds of good taste and offends Finnish identity.” This and the aforementioned otherness-promoting discourses support my original assumption that the Mormons are to some degree regarded as foreign in Finnish society.

The Religious Media and Ecclesiastical Representatives: “Interest Can Be Dangerous”

The religious media reflect the attitudes of the general media toward Mormonism but with a particular emphasis and from a different perspective. While the general media may be more interested in the position of religions and churches as actors in society at large, the religious media and ecclesiastical representatives are often interested more in questions of faith content and theology.

In the case of the religious media and ecclesiastical representatives, word choice and particularly its mental associations create a window into the religious values of the person who employs the particular discourse of othering.[53] And since religious newspapers, for example, are often the organs of specific churches, they may emphasize the drawing of boundaries between themselves and other churches and religious movements. Ecclesiastical representatives may also feel that the drawing of such boundaries is necessary in their public comments.

One could surmise that religious actors in a secularized society would show understanding and less prejudice toward other churches that are also fighting the common problem of secularization and indifference toward organized religion. However, these religious actors also take part in discourses of othering and in drawing distinct boundaries. Their reasons lie in matters such as mutually contradictory truth claims, cultural differences, and perceived rivalry.[54]

Examples of both affinity and rivalry can be seen in connection to the Mormon temple in Finland. A former minister of the Lutheran Leppävaara Parish in Espoo gave some positive public statements concerning the temple. For example, he thought that the temple was beautiful to the point of nearly arousing envy and that the Mormons were dedicated people with high morals. He “doesn’t see the Mormons as competitors.”[55]

On the other hand, about a dozen signatories announced to Espoo city officers that they objected to “the Mormon heresy’s coming to their home area.”[56] The boundary between Lutherans and Mormons is also clear when the parish minister hopes that the Lutheran Church will be believable enough, so “that people won’t feel the need to change religion.”[57] One writer thanked the Espoo Parish Union for drawing a clear boundary in its newspaper “on the strange doctrine that has become situated in the area of its parishes.”[58]

In the next section, I describe some discourses of othering brought up by the religious media and by ecclesiastical representatives. For thematic examples, I have chosen the contested Christian identity of Mormonism, the drawing of boundaries, and the temple’s religious ceremonies.

“The Mormons’ Doctrine Deviates Greatly from Christianity”

The term “Christian” is problematic due to its multiple definitions. Parties can define the term in a way suitable to them in order to make their own division between Christians and non-Christians or, sociologically speaking, between “us” and “them.” Protestants, for example, often want to draw a boundary and create a dichotomy with Christians on one side and Mormons on the other. Mormons, on the other hand, regard themselves as clearly Christian and sometimes wonder how anyone can think differently. The situation is problematic: Who has the right to judge which definition of the term “Christian” is correct and which definitions of Christian terminology and symbolism are correct? An analysis of religious newspapers shows that some Finnish Protestants do not like the Mormon way of using familiar terminology with meanings different from Protestant custom. Mormons may in those cases be thought of as misleading evangelizers and may even be accused of “duplicitous ecumenism.”[59]

The religious media and ecclesiastical representatives sometimes connect Mormons with new religions that have their basis in Christianity. However, sometimes they say clearly that the Mormon Church is not Christian,[60] basing their exclusion, for example, on theological arguments concerning the atonement of Jesus Christ or on the Mormons’ rejection of the traditional Christian creeds.[61] Sometimes they justify their exclusion in part by arguing that “Christian churches” do not accept the Mormons as Christian.[62] This appeal to majority opinion is an example of the difficulty of making a judgment based on objective criteria.

One representative of the Free Church compares Protestantism with Mormonism and uses the expression “the thing that makes Christian truth superior” in referring to the crucial difference.[63] By doing so, he creates an interesting dichotomy; the wide diversity of the Christian ingroup is diminished, perhaps owing to the crucial importance of maintaining the boundary. In reality, of course, “Christian truth” is not a monolithic whole but rather consists of a great variety of diverging opinions. The diminishing of the differences within one’s own ingroup can be done for effect in a discourse of othering.

Finally, the relationship between Protestants and Mormons may sometimes feel uncomfortably unclear for the Protestants themselves. The following comment shows the uncertainty that can surface when boundaries are unclear: “Christ has a very central place in their doctrine. Then again their concept of God is very different than the one people are used to in Christian Churches. . . . Many Christians think that it is easier to deal with religions clearly different from one’s own faith, such as Islam or Judaism, than with the kind of ‘cousin’ of the Christian faith as Mormonism. In the latter case one contradictorily feels both close and far away at the same time.”[64]

“Mysteries and Secrets, Closed Temples and Unknown Religions”

In addition to denying the Christian identity of Mormonism, the religious media found other reasons to be suspicious of the temple construction project. According to one observer, the project meant that “an American faith is conquering Finland.”[65] Finland was seen as a mission field “where souls are fought over”[66] and where the Mormons would begin to operate more eagerly than before.

Half-humorously, one writer mused on the difficulty of abstaining from alcohol, coffee, and tea and decided that she would “remain Lutheran after all.”[67] A letter to the editor stated: “I cannot refrain from informing Kyrkpressen’s Christian readers that the Mormon Jesus is a brother to Lucifer. The one with the horns.”[68] The writer did not attempt to describe the Mormon belief in a premortal existence in which all beings, mortal and supernatural, Jesus and Lucifer included, are brothers and sisters. Thus, the letter creates an even more strongly alienating image of Mormon theology.

As might be expected, the religious media tended to be suspicious of the secret Mormon temple ceremonies. One writer characterized the Church as “nearly like a sect of freemasons.”[69] Another reporter stated that “a Mormon has to perform secret oaths and rituals in the temple.”[70] The depiction is technically accurate, but a Mormon would probably have chosen the words “sacred ordinances” instead of the more frightening words “oaths and rituals.” As a parallel example, an outsider perspective of the Christian communion could create an even stronger image of foreignness by depicting it as a cannibal feast, where believers eat and drink their god’s flesh and blood. The depiction is technically correct but generates strong feelings of otherness and completely ignores the symbolic and well-known meaning of the communion to the believers themselves.

One writer regarded the Mormon form of church government with suspicion, calling it an “aggressively authoritarian” organization that sought to “control the entire lives of its members.”[71] Another writer described it as a “syncretistic composite religion,”[72] possibly meaning that it was a compound of elements from Christian and non-Christian sources. From a larger perspective, one can, of course, view Christianity itself as a syncretistic composite religion. In any case, one-sided choices of words and perspectives distance and alienate Protestant readers from Mormons and create sometimes alarming images of otherness.

“Next to Desecrating Graves and Tampering with the Deceased”

The concept of proxy ceremonies was dealt with in the religious media and by ecclesiastical representatives with greater disapproval than by the secular media. Christian baptism has been thought of as a once-in-a-lifetime event, and proxy baptism can thus be seen as meddling with the faith choices of a deceased person. In Finland, proxy baptisms aroused such strong feelings that their compatibility with legislation on religious freedom has been called into question. In answer, an officer of the Ministry of Education, which is the highest authority in matters of religion and state in Finland, pronounced proxy baptisms as being within the bounds of the law.[73] A letter to the editor reported that a feud among some older persons in an extended family had broken out due to proxy baptisms having been performed by a young LDS relative.[74]

Representatives of the Lutheran and Orthodox Churches have at times been very critical of proxy baptisms. For example, the archbishop of the Finnish Orthodox Church was reported as stating that proxy baptisms are “a completely impossible and unbelievable thing: baptizing popes and marrying nuns. Just preposterous.”[75] The bishop of the Lutheran Church’s Kuopio Diocese felt Mormon activities were “dubious” and that proxy baptisms were akin to “desecrating graves.”[76] A representative of the Tampere Parish Union stated that the Lutheran Church “does not in any form approve of the Mormon custom of baptizing the dead.”[77]

When criticizing Mormon proxy baptisms, the Protestant mainstream does not usually acknowledge that Christian theology itself could be criticized on the same basis: It requires belief in the doctrine of a Savior who atoned in behalf of every person. An officer of the Ministry of Education came up with another similarity: “I don’t know if we’re talking about anything much different from a Christian praying for somebody who is dead even though that person may not be a Christian.”[78] Regardless of these similarities, many religious writers have portrayed proxy baptisms as foreign and unsuitable in the Finnish religious landscape.

Thus, generally speaking, it can be said that the otherness-promoting mode of discourse used by the religious media and ecclesiastical representatives is stronger than that employed by the general media, although there are exceptions.[79] They feel that more is at stake than just relaying information on the Mormons. In their eyes, the Mormons are not only culturally foreign but also religiously heterodox actors who compete for the same resources and individuals, and against whom one’s own troops must be “vaccinated.”

Finland’s Mormons: “We Would Like for This Veil of Mystery to Be Taken Away”

During the nineteenth century, Latter-day Saints tended to withdraw from the rest of society and define their identity by differentiating themselves from others. The internal discourse often maintained an image of the rest of the world as evil and of their own group as the only place of salvation. During the twentieth century and especially toward its end, Mormonism changed and, at present, seeks to identify itself to some extent in the general population’s mind with Protestant and Catholic Christianity, normal “mainstream Christianity.” Ignoring their polygamous past and other eccentricities, Latter-day Saints seek to generate an image that emphasizes the general Christian features of their faith.

To some extent this desire is justified, because much misleading and sensationalistic information on the Mormons has been distributed throughout the years, a problem Mormonism shares with many other religious minorities. On the other hand, this mainstreaming discourse may in itself create a misleading image of the Latter-day Saints, because Mormonism also has clear differences from traditional Christianity. Latter-day Saints have also been accused, often on solid grounds, of withholding their higher and more controversial teachings from the general public through this mainstreaming discourse.

The public open house at the Helsinki Temple gave the Mormons in Finland an opportunity to employ their otherness-diminishing discourse in public outside their own publications. According to a public affairs representative, the open house was a clear opportunity “to increase knowledge concerning the Mormon religion and to rectify flawed views.”[80] In a nationally televised interview prior to the open house, another public affairs representative hoped that the forthcoming publicity would improve the Mormon Church’s image in Finland: “We believe that the completion of the temple will bring at least good publicity. The completion of the Copenhagen Temple in 2004 didn’t really bring new members, but attitudes toward the Church changed. The Church became a better match with society. This will hopefully happen also in Finland.”[81] In the following section, I will deal with some LDS ways of utilizing an otherness-removing counter-discourse in connection with the Helsinki Temple open house. As themes, I have chosen the emphasis upon the normalcy of the Church and its members, the temple and its ceremonies, and Mormon Church relationships with Finland.

“When They Learned to Know, the Prejudice Departed”

One way that the LDS Church sought to promote a familiar image of itself was by referring to its worldwide dimensions. One newspaper article quoted a foreign Mormon leader at the temple open house as stating that the Mormon Church is “one of the fastest-growing churches in the world.”[82] The Mormon-produced press package also claimed that the Church is “one of the world’s fastest-growing Christian churches.”[83]

The Church’s growth since the second half of the twentieth century has, in fact, been numerically impressive. It has grown from a 1 million member denomination to a worldwide church with more than 12 million members. However, claims of rapid growth are to some extent misleading. The Church typically reports only numbers of members of record without acknowledging informal disaffiliations or even that some members’ whereabouts are unknown. Unless members formally resign or are excommunicated, they continue to be counted as members, even though they may no longer regard themselves as Mormons. This is one reason that Mormonism is still in many ways a North American phenomenon, although large numbers of baptisms have been performed elsewhere.[84]

In some highly secularized countries including Finland, actively religious individuals of whatever denomination is sometimes thought of as peculiar. In connection with the temple open house, Mormons sought to emphasize their normalcy. An American sister missionary working in Finland, for example, commented on claims of peculiarity by saying that “we do, for example, use makeup and watch TV; we do normal things.”[85] A Mormon public affairs representative on national television described herself and her husband as attending “all kinds of places” and social events without, for example, drinking coffee or alcohol. But “we haven’t been considered oddities in any way.” She also emphasized that Mormons do not use external religious symbols, that they invest in education, and that they belong to all classes of society. She tries to “live as probably every other Christian person tries to live,” thus emphasizing the Mormon identification with Christianity.[86] “The Church offers a healthy way of life that fits with modern times,” commented a Mormon bishop in Espoo. He continued: “The Church is at its best when it offers its members solace and safety.”[87]

In Finnish society, the most easily recognizable Mormon image is the missionary stereotype: Dark-suited Americans who speak Finnish with a distinct accent and go from door to door explaining their faith and Church. Their presence has even made its way into Finnish popular culture.[88] During the temple open house, the Mormons emphasized that the door-to-door technique was less utilized at present as “not so suitable in Finnish culture.” For example, missionaries had been serving as officials in the Jyväskylän Suurajot rally.[89]

Religious evangelization is sometimes thought of as negative and pushy with a message that people are not really interested in. Although the ultimate goal of LDS missionaries is for individuals to accept the doctrines of the Mormon Church and join it, this purpose can move to the background in normalcy-emphasizing discourses. According to a public affairs representative, for example, the missionaries are “not so much seeking to convert, but to help people find a new lifestyle.”[90] She is speaking of the same thing, but the mainstreaming discourse presents the matter in a more neutral manner.

Mormons have also emphasized their Christian identity,[91] explaining the lack of the Christian cross in Mormon iconography as a desire to concentrate on Jesus as a living person. A typical explanation is: “Although we are a Christian Church, we don’t use the cross, since we want to remember Jesus as a living person, not as a dead person.”[92] However, since the presence of the cross does not prevent Christians from believing in the resurrection (and, hence, in Jesus as a living person), it seems reasonable to ask to what extent the omission of the cross represents early Mormonism’s efforts to draw a boundary between itself and mainstream Protestantism.[93]

“There Is Nothing Secret [in the Temple]”

The ceremonies of the temple are very sacred to Latter-day Saints. The ceremonies are not discussed in detail with persons not of the faith, with Church members who have yet to participate in them, or even with other temple-going Mormons outside of the temple itself. The esoteric, symbolically “unwritten” nature of the ceremonies promotes an experience of sacredness and strengthens the social ties of the members.[94] Consequently, in the minds of the non-Mormon public, Mormon temples are a mystery. Moreover, narratives concerning temples by former Mormons may reinforce the foreign and mysterious image.

A public open house at a new temple is thus always an interesting challenge for the Mormon Church: how to inform the public in an understandable, clear, and normalcy-emphasizing manner, while at the same time preserving the esoteric nature of the ceremonies. Latter-day Saints themselves emphasize the sacred nature of the temple and usually sidestep the esoteric nature of the ceremonies. The Church’s spokesman in Finland,[95] for example, stated in a nationally televised news interview, “There is nothing secret there. We think there are sacred things there, and now we have the chance to show it and tell about it to people.”[96] Similarly, a public affairs representative said in another nationally televised interview, “There are no mysterious rituals connected with visiting the temple, but instead everything is very beautiful, simple, symbolic, and pure.”[97] In practice, the ceremonies are partly secret chiefly because of their sacredness, as was clear during the guided tours during the open house. Of course, a reasonable question is the practical issue of trying to engage laypersons in discussions of ceremonies and symbolism that require a deep understanding of Mormon theology, especially in an open house setting where time is limited and conditions are crowded.

Latter-day Saint explanations of temple ceremonies usually emphasize the “family-centered” nature of the ceremonies and often mention eternal marriage and proxy baptisms for the dead. Mormons think of these ceremonies as uniting families for eternity, and the person in the street can connect marriage and baptism with his or her own experiences. Allusions to the endowment ceremony proper are more vague, while initiatory ceremonies are even rarer in public descriptions of the temple ceremonies by Mormons. LDS spokespersons usually stick to a general explanation that the temple teaches the purpose of life.

As has been mentioned, proxy baptism has been met with criticism as tampering with the religious choices that the deceased made during his or her lifetime. Mormons themselves have acknowledged that people may consider such a state of affairs offensive, and a public affairs representative in Finland commented: “Because of that we neither baptize or perform marriages for other deceased persons than our own relatives,”[98] and “The custom is that our Church’s members want to give their deceased relatives a chance” to accept the gospel in the next life.[99] This limited and misleading picture, which ignores the hundreds of thousands of ordinances performed by nonrelatives through name extraction programs, is probably motivated to promote a discourse of mainstreaming.

In contrast, other Latter-day Saints have sometimes clearly explained that, while proxy ceremonies are primarily performed in behalf of the deceased relatives of Mormons, the activity is not limited to them. Another Church public affairs representative commented that “the purpose is to give everyone a chance, and they will then decide whether they accept baptism or not. There should not be anything stranger in it than that.”[100] Mormons have emphasized that proxy ceremonies do not bind the deceased in any way nor change their religious choices against their desire. Mormons have also compared proxy baptisms to the universal nature of Jesus’s atonement.[101]

However, the universal nature of proxy work has sometimes placed the Mormons in difficult situations. For example, because God’s justice in principle requires that salvific ceremonies be performed by proxy for all those that did not take part in them while alive, in order to give the same chance to everyone, they have been performed also in behalf of Adolf Hitler. From the Mormon point of view, such a step is theologically consistent because Hitler was, despite his atrocities, a human being like everyone else. Others have been shocked that Mormons consider such a person worthy of salvation and would be willing to associate with him on any basis. Perhaps partly due to the difficulty of explaining this theological point, the Church has erased these ceremonies from its records and stated that it is not appropriate to perform proxy work for persons such as Hitler.[102] Some Finnish Mormons have mistakenly denied, for example, that a proxy sealing has been performed for Adolf Hitler and his mistress, Eva Braun, although such a ceremony has in fact been performed. When a newspaper reported this fact and a Mormon spokesperson requested a correction, the newspaper that reported these “hair-raising rituals” obliged by stating that “the article’s claim that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun would have been married later is not accurate, either.”[103]

Latter-day Saints maintain a database of those in whose behalf proxy temple ceremonies have been performed. In contrast to other genealogical information provided by the Church which is openly available on the internet, the temple ordinance files are not. Attempts to obtain the information have raised suspicion in the minds of some non-Mormon Finns.[104] A Church public affairs representative sought to erase this suspicion by claiming that “all information is freely available to everyone. There are no secret registers, only normal genealogical information.”[105] This statement is accurate except that it applies only to genealogical (i.e., birth, marriage, and death dates) information, not temple ordinance data. In summary, although it is true that the symbolic meaning of the temple ceremonies would be difficult to explain in a brief, clear way, it can also be claimed that the Mormon Church does not explain its temple ceremonies in a more detailed manner to defuse its image of otherness. Nonetheless, despite the efforts of the Latter-day Saints to appear normal, the secrecy of their temple ceremonies maintains a boundary between them and the Finnish population in general.

“The Atmosphere in Finland Used to Be Different. . . . Fortunately Things Are Different Now”

In their mainstreaming discourse, the Mormons have also emphasized the connection between the Church and Finland. During the guided tour at the Helsinki Temple, for example, the introductory video explained how Finnish President Tarja Halonen had met LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley in connection with the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics, and how Mormon missionaries helped out in the 1952 Helsinki Summer Olympics. Presumably these items were mentioned to reduce the boundaries between the Finnish identity and Mormonism and bolster the credentials of Mormonism among the Finns.

The Church’s spokesman in Finland also emphasized how architects worked to make the temple’s architecture compatible with Finnish designs. He stressed a common element: “This kind of rising, strong tower stands out on Finnish churches.”[106] He also commented reassuringly that “there were no problems with obtaining the building permit.”[107] No Mormon mentioned the earlier less-than-enthusiastic general reactions from the cities of Helsinki and Vantaa in any media reports that I have seen, thus muting a source of possible differences.

However, some Latter-day Saints also acknowledge their label of foreignness on the Finnish religious landscape. According to the Church’s spokesman, “General lack of awareness of us is perhaps our greatest problem.” A Finnish Mormon who had been to the United States compared the religious atmospheres of both countries and contrasted the U.S. acceptance of religious pluralism with Finland’s general uniformity and lack of religious interest. “In Finland you do not talk that much about religion. If you do not belong to the state religion, then it is something different,” she stated in an interview on a national television network.[108]

At the same time, Mormon discourse lowers boundaries by emphasizing that the atmosphere has changed and that diversity is better tolerated nowadays. “Contemporary youth have a lot of knowledge and they are open-minded, which reduces unnecessary prejudice,” a Mormon bishop commented in a newspaper interview.[109] When people “learn to know,” prejudice departs.[110] The open house at the Helsinki Temple gave the Latter-day Saints an excellent opportunity to help Finnish people “know.”

Summary and Discussion

This article has dealt with the Helsinki Finland Temple open house through the perspective of discourses on Mormon otherness in Finnish society. I have focused on three different viewpoints, each with a limited number of representative themes: the general media, the religious media and ecclesiastical representatives, and Latter-day Saints themselves.

Themes in the general media dealt with matters such as the temple as an atypical building and construction site, American features in the Mormon Church and the temple’s architecture, and proxy ceremonies performed in the temple. The religious media and ecclesiastical representatives dealt more deeply with Mormonism by approaching its theology, comparing LDS doctrines with “Christian” doctrines. The result was usually to distance Mormons from what was seen as the Christian ingroup. In all, the entire spectrum of media contained fairly similar and clear discourses that strengthened the foreign image of Mormons in Finland to varying degrees.

Mormons themselves sought to reduce their image of otherness and to be regarded as a legitimate and normal part of Finnish religiosity. They emphasized the sacred nature of the temple and its meaning to them, downplaying or not mentioning the temple’s symbolic ceremonies but instead presenting them in general statements about the purpose of life and the important family-building ceremonies of proxy baptism and eternal marriage. Mormons also reminded the public that they consider themselves to be part of Christianity.

Although Mormons are thought of as foreign and as representatives of “the other” in Finnish discussions, they are not unique; any religion different from Lutheranism probably must explain its doctrines and existence. This is true for Christian minorities, immigrant religions, and new religious movements. Mormonism’s status as “foreign” in Finland is also interesting because, while the highest leadership mostly comes from the United States, the local membership and leadership in Finland consists of Finns. Those adhering to Islam and Hinduism in Finland, in contrast, are usually immigrants and often of visibly foreign origin. Does this Finnish element diminish the image of Mormons as foreign in Finland? Or, in contrast, does Mormonism in Europe practically demand that its adherents replace pieces of their own national culture with American-colored features—becoming, in anthropologist Walter van Beek’s terms, “European Mormons” instead of “Mormon Europeans?”[111]

On the whole, it can be argued that the wide media coverage of the open house at the Helsinki Temple tended to make Mormons less other. Invisible psychological barriers about visiting the temple diminished as generally positive news reports came out and as early visitors told friends about their own experience. The success of the open house had a snowball effect (indications of which are seen in Table 1), resulting in more visits than the popular fair featuring summer vacation homes, arranged that year in Koli, northern Finland (approximately 56,000 versus 38,000). Many visitors even had to queue in the rain, but they still wanted to see the Mormon temple. Of course, the temple’s location in the well-populated capital city region certainly helped produce the relatively high number of visitors.

It is important not to skew the overall picture, keeping in mind that most Finns did not visit the temple and that some visitors had a negative or indifferent experience (not reported in this article). Still many people clearly felt very positive about what they saw and the peace and beauty they experienced. Church members were mostly happy about their friends visiting and reckoned that the experience had reduced feelings of foreignness. A Finnish Latter-day Saint explained: “For years, family and neighbors have thought us to be different. A group of 10 colleagues came. They felt the spirit of the edifice and shed tears. Now they understand my life. It is not strange to them anymore.”[112]

The Church gathered comments from visitors by making available a feedback form in the refreshment tent after the guided tour. Nearly 6,000 forms were returned and would constitute an interesting corpus for further study. What did people think about what they saw? Did their image of the Mormons become less or more foreign, or was it foreign to begin with? Were their preconceived notions strengthened or did their thoughts change? The source material is not, of course, representative of all Finns because of the method through which it was gathered; but such a study could nevertheless provide interesting perspectives on Finnish religiosity and Finnish people’s thoughts as they got acquainted with a religion many perceive as being foreign.

However, one must also be cautious not to overemphasize the degree to which the Mormons actually are thought of as foreign in Finnish society. Much reporting was positive from the Mormon point of view, praising the aesthetics and peacefulness of the temple. Articles also mentioned features of Mormonism that were thought of as “normal” in Finnish society, such as routine Mormon participation in military service.[113] A fairly lengthy radio interview with a Finnish Mormon lawyer profiled him as a well-educated and busy professional man and father in whose life faith is an important component.[114]

Conversely, it is also important to acknowledge that the Mormons themselves maintain boundaries between themselves and mainstream Finnish society. Accompanying the mainstreaming discourses emphasized in this article, the Church has practices that clearly strengthen an image of otherness. For example, the LDS Church in Finland does not participate in ecumenical cooperation with Christian churches except in providing humanitarian aid, rarely takes part in societal activities in a visible way, and does not usually announce its local activities through established information channels such as newspapers. The temple tradition is itself exclusive. Not even all believers are automatically welcome in Latter-day Saint temples.

The Mormon Church is thus, like other churches, continuously facing the challenging problem of optimum sociocultural tension mentioned earlier. How may it balance inclusiveness and exclusiveness so that its own doctrine and core identity are not excessively diluted and so that the tension between itself and society at the same time is not so strong as to inhibit growth? This question in and of itself would form an interesting field of research with regard to changing Mormon identity and avoiding an otherness-promoting public image in Finland. Comparative data already exist from the perspective of Mormonism in the United States.[115] It must also be kept in mind that the rough division into general and religious media that this article used for reporting convenience disguised nuances among different actors that belong to the same group. In general, looking at media groups as monolithic entities can be misleading. Nevertheless, I have chosen this approach to provide a detailed overview from one particular sociological perspective. In the future, it would be interesting to compare a broader report of publicity associated with the Helsinki Temple with publicity connected to new temples and their open houses elsewhere. Scandinavia alone, for example, would provide comparisons with the 1985 open house of the Stockholm Sweden Temple and the 2004 Copenhagen Denmark Temple, at least the latter of which used approaches, models, and publicity materials very similar to those employed in Finland. Comparisons with temples in other countries and on other continents would provide further illumination.

Conclusion

In this article, I have discussed otherness-promoting and otherness-removing discourses related to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Finland. My data came from publicity related to the newly completed Helsinki Finland Temple, specifically comments and statements by professional media journalists, religious entities and representatives, and the Latter-day Saints themselves. The findings show that the Latter-day Saints do indeed have a foreign image in Finland. Finnish media projected an image of the Latter-day Saints as “the other” through, for example, evidence of American culture, allegations of suspicious activities, and deviation from traditional Christianity. Latter-day Saints, for their part, often employed a counter-discourse intended to emphasize the normalcy of Mormons as Finnish citizens with a worldview slightly different from that of the mainstream.

The completion of the Mormon temple in Espoo and the accompanying publicity thus provided a clear example of the existence of otherness-promoting and otherness-diminishing discourses for one religious minority in Finland. The participants looked at matters from their own perspective, which framed and shaped their comments. The mainstream Finnish population finds the Mormons foreign in many ways, while Mormons themselves feel that they are simultaneously part of the regular mainstream population in many ways yet different from it. As is so often the case when constructing an image of society and evaluating the place of various groups in it, the problem culminates in difficult questions. Where should the boundaries of a questionably homogenous mainstream be drawn? And perhaps most important of all, who is authorized to draw them?

[Editor’s Note: For the Appendices, see the PDF below.]

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Jan Shipps, “No More ‘Mormon’ Church?,” Sunstone Symposium, Washington, D.C., 2001. Audio online at http://www.sunstoneonline.com (accessed October 1, 2005).

[2] Data from the chronological listing, http://www.ldschurchtemples. com (accessed January 21, 2007).

[3] I sincerely thank all those individuals who have helped me compile the database of material that served as the basis of this study and without which it would not have been possible to conduct the study. The English translations of most of the quotations from Finnish or Swedish in this article are mine. I have also provided English translations of newspaper article headings in parentheses and of newspaper names or broadcast program names in brackets on first usage.

[4] The temple district consists of the countries of Belarus, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Russia (partly). I’ve limited my material to items published in Finland, although there was some publicity in at least neighboring Estonia.

[5] I have collected much of the material by monitoring media outlets closely, especially during the public open house, assisted by several interested individuals located around Finland. Additionally, I have been in contact with Mormon Church Public Affairs in Finland in order to benefit from that office’s findings. The resulting database seems more than sufficient, especially as the purpose of this article is not to give a full overview of all media attention to the new Mormon temple, but rather to give examples of certain types of discourses related to the Mormons.

[6] Martti Junnonaho, “On Religious Otherness in Finnish Discourse,” in Beyond the Mainstream: The Emergence of Religious Pluralism in Finland, Estonia, and Russia, edited by Jeffrey Kaplan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2000), 191–99.

[7] Tuomas Martikainen, “The Houses of Foreign Gods,” in Urbanism and Globalization, edited by Frank Eckardt and Dieter Hassenpflug (Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang, 2004), 180.

[8] Grace Davie, Religion in Modern Europe: A Memory Mutates (Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 2000), 3.

[9] Kimmo Kääriäinen, Kati Niemelä, and Kimmo Ketola, Religion in Finland: Decline, Change and Transformation of Finnish Religiosity (Tampere, Finland: Church Research Institute, 2005), 79.

[10] Kim B. Östman, “The Mormon Espionage Scare and Its Coverage in Finland, 1982–84,” Journal of Mormon History, 33, no. 1 (Winter 2008).

[11] Walter E. A. van Beek, “Mormon Europeans or European Mormons? An ‘Afro-American’ View of Religious Colonization,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 38, no. 4 (Winter 2005): 3–36.

[12] Rodney Stark, “Why Religious Movements Succeed or Fail: A Revised General Model,” in Cults and Religious Movements: A Reader, edited by Lorne L. Dawson (Malden, Eng.: Blackwell, 2003), 259–70.

[13] For a theoretical discussion of the concept of sociocultural tension, see, for example, Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge, The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival, and Cult Formation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 19–24.

[14] Martikainen, “The Houses of Foreign Gods,” 175–89.

[15] Pia Karlsson, “Making Room for Islam—Mosques in Sweden,” in Islam and Christianity in School Religious Education: Issues, Approaches, and Contexts, edited by Nils G. Holm (Åbo, Finland: Department of Comparative Religion, Åbo Akademi University, 2000), 183–202.

[16] “Kirkko valittiin mallikirjasta” (“Church Chosen from a Model Book”), Helsingin Sanomat [Helsinki Gazette], July 21, 2006, A10.

[17] Gordon B. Hinckley, “A Time of New Beginnings,” Ensign, May 2000, 87.

[18] In addition to the public open house, tours were also organized for construction workers and their families on September 16, for VIPs and the media on September 19–20, and for workers at the Stockholm Sweden Temple and their families on October 8. I include the number of visits from these days in the total number of visits. The temple was closed on Sundays, which is interesting, considering that Temple Square and the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City are open on Sundays.

[19] Kääriäinen, Niemelä, and Ketola, Religion in Finland, 79.

[20] Sami Myllyniemi, “Nuorisobarometri,” in Uskon asia—Nuorisobarometri 2006, edited by Terhi-Anna Wilska (Helsinki: Nuorisoasian neuvottelukunta, Nuorisotutkimusverkosto ja Nuorisotutkimusseura, 2006), 79.

[21] Sari Pietikäinen and Heikki Luostarinen, “Vähemmistöt suomalaisessa julkisuudessa,” in Vähemmistöt ja niiden syrjintä Suomessa, edited by Taina Dahlgren et al. (Helsinki: Yliopistopaino, 1996), 172.

[22] Junnonaho, “On Religious Otherness in Finnish Discourse,” 196.

[23] Pietikäinen and Luostarinen, “Vähemmistöt suomalaisessa julkisuudessa,” 178.

[24] See Markku Ihonen, “Mediakummajainen? Herätysliikkeen julkisuusongelmien äärellä,” Tiedotustutkimus 23, no. 4 (2000): 68–78, for the case of Laestadians in Finland.

[25] “Open Hearts Abound: Some 56,000 Finns Attend Open House of New Temple,” Church News, October 28, 2006, 7.

[26] Pietikäinen and Luostarinen, “Vähemmistöt suomalaisessa julkisuudessa,” 175, 184.

[27] “Uskonystäviä syytetään naisen surmanhypystä parvekkeelta Kangasalla” (Faith Friends Accused of Woman’s Death Jump from Balcony in Kangasala), Aamulehti [Morning Paper], November 7, 2006, A7.

[28] Stephen Harold Riggins, “The Rhetoric of Othering,” in The Language and Politics of Exclusion: Others in Discourse, edited by Stephen Harold Riggins (Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1997), 25.

[29] “Mormonitemppelin rakentaminen on kolmen vuoden urakka: Temppelin työmaalla ei kiroilla eikä tupakoida” (Building of Mormon Temple is a Three-Year Job: No Swearing or Smoking on Temple Work Site), Länsiväylä [Western Route], May 25, 2005, 4.

[30] “Millintarkka temppeli” (A Millimeter-Precise Temple), Rakentavasti [In a Constructing Manner], Summer 2005.

[31] “Mormonitemppelin rakentaminen on kolmen vuoden urakka.”

[32] “IHAN vähän amerikkalaista” (JUST a little American), Vartti [Quarter], September 24, 2006, 6.

[33] “Helsingin uuteen temppeliin tutustuu tuhansia ihmisiä: Lars Gröndahlilla fantastinen tunnelma” (Thousands of People Getting to Know New Helsinki Temple: Lars Gröndahl Feeling Fantastic), Loviisan Sanomat [Loviisa Gazette], September 29, 2006, 12.

[34] Horisontti [The Horizon], Yle Radio 1, September 24, 2006, emphasis added.

[35] Ylen aikainen, Yle Radio Suomi, October 3, 2006.

[36] “IHAN vähän amerikkalaista,” 6.

[37] Ylen aikainen, Yle Radio Suomi, October 3, 2006.

[38] “Tung utanpå, prålig och glittrig inuti” (Heavy on the Outside, Fancy and Glittery on the Inside), Hufvudstadsbladet [Capital City Paper], September 20, 2006, 4.

[39] “IHAN vähän amerikkalaista,” 6.

[40] “Valoa kansalle Amerikan malliin: Suomen ensimmäinen mormonitemppeli häikäisee prameudellaan,” (Light for the People in the American Way: Finland’s First Mormon Temple Dazzles with Its Glitter) Iltalehti [Evening Paper], September 20, 2006, 12–13. In contrast are other glowing descriptions of the interior that make no reference to American architecture. See for example “Kirkko kuin koru” (Church like a Piece of Jewelry), Seura [Company], 72, no. 39 (September 29, 2006), 14.

[41] “Valoa kansalle Amerikan malliin,” 12. “Rapakon takana,” meaning “beyond the puddle,” is a Finnish saying sometimes used when referring to the United States on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

[42] Seitsemän uutiset [Seven o’clock News], MTV3, September 19, 2006.

[43] Ylen aikainen, Yle Radio Suomi, October 3, 2006.

[44] “Vainajia kastetaan pian täällä” (The Deceased Will Soon Be Baptized Here), Ilta-Sanomat [Evening Gazette], April 17, 2004, 12–13.

[45] “Vainajakaste” (Baptism of the Deceased), Satakunnan Kansa [The People of Satakunta], April 23, 2004, 1.

[46] “Kastettavana vastoin tahtoaan” (Baptized against One’s Will), Metro [Metro], April 29, 2004, 6.

[47] “MAP-kirkko pystyttää temppeliä Espooseen: Esi-isämme kastetaan mormoneiksi” (LDS Church Erecting Temple in Espoo: Our Forefathers Are Baptized as Mormons), Nykyposti [Modern Post], 27, no. 5 (2004): 14–18.

[48] Maria Ollila, “Käsin kopioinnista mormonien rahoittamaan mikrofilmaukseen: Suomalaisten kirkonkirjojen jäljennystyö 1924–1955” (M.Th. thesis, University of Helsinki, 2003).

[49] “Sex gånger döpt” (Baptized Six Times), Vasabladet [The Vaasa Paper], September 23, 2006, 11.

[50] “MAP-kirkko pystyttää temppeliä Espooseen: Esi-isämme kastetaan mormoneiksi,” Nykyposti 27, no. 5 (2004): 16.

[51] “Mormonien kasterekisteri arveluttaa tietosuojavaltuutettua” (Data Protection Ombudsman Iffy about Mormon Baptism Register), Ilta-Sanomat, April 20, 2004, 11.

[52] “Vainajia kastetaan pian täällä.”

[53] Pietikäinen and Luostarinen, “Vähemmistöt suomalaisessa julkisuudessa,” 184.

[54] Gordon W. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979), 444–57.

[55] “Laaja keskus palvelee myös Venäjää ja Baltian maita: Espooseen kohoaa mormonitemppeli” (Large Center also Serves Russia and Baltic Countries: Mormon Temple Rises in Espoo), Kotimaa [Homeland], 101, no. 28 (July 14, 2006): 3. A new parish minister has also been positive. Quoted in “Miten seurakuntaan lisää jäseniä Leppävaarassa?” (How to Get More Members in Leppävaara Parish?), Länsiväylä, January 17, 2007, 4.

[56] Espoo city planning board minutes, September 11, 2002. Nonetheless, in comparison with many other planned Mormon temples (e.g., Boston), the Helsinki Temple project seems to have proceeded with minimal protest-related problems.

[57] “Laaja keskus palvelee myös Venäjää ja Baltian maita: Espooseen kohoaa mormonitemppeli,” 3.

[58] “Mormonien ja kristinuskon erot” (The Differences between Mormons and Christianity), Verkko-Esse [Net-Esse], http://www.esse.fi accessed October 3, 2006).

[59] “Emävale-ekumeniaa” (Duplicitous Ecumenism), Sanansaattaja [The Messenger], 131, no. 40 (October 5, 2006): 2.