Articles/Essays – Volume 45, No. 1

The Truth Will Set You Free | Errol Morris, Tabloid

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

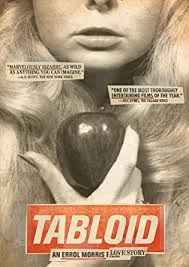

Tabloids, it seems, make good headlines. When Errol Morris’s new film Tabloid began its limited release on July 15, 2011, British papers were themselves dominating the news, with the News of the World closing its doors on July 10 and Rupert Murdoch appearing before Parliament less than two weeks later. The timing was weirdly appropriate: Morris’s film examines an episode from 1977 when the British papers were awash with the story of Joyce McKinney, an American girl alleged to have abducted a Mormon missionary and briefly made him her sex slave. In looking at the tactics of tabloid reporters in 1977, it seems that not much has changed. Surely the reporters then would have hacked McKinney’s mobile phone had they been able.

But Tabloid is also a film that deals extensively with Mormonism, so it is appropriate that it be released at a time when Mormons are again ascending the world stage. The June 13 Newsweek cover proclaimed the headline “The Mormon Moment,”a view seconded a month later by the New York Times.As the articles explain, with the phenomenal success of The Book of Mormon on Broadway, two Mormon presidential candidates, the culmination of Big Love on HBO, and the prominence of Mormons like Harry Reid, Stephenie Meyer, and Glenn Beck, the Church is receiving more scrutiny—and possible acceptance—than ever in its history. Mormon viewers of Tabloid can then profitably ask themselves whether public opinion and press coverage of the Church have improved in the last thirty-four years, or if headlines about “the Manacled Mormon” would still find acceptance today.

Tabloid tells its story by doing what Morris does best: identifying one remarkable individual and delving as deep into her psyche as possible. And Joyce McKinney is indeed remarkable—Morris has called her his “favorite protagonist.”What makes her so compelling? She’s charismatic, persuasive, and determined— great qualities for the camera all—but it is primarily the enigma of her story that lends her so well to Morris’s vision. As she tells it, she had a fairytale romance with a young Mormon named Kirk Anderson until his church snatched him away and sent him to England. She followed, rescued him (at gunpoint), and took him to Devon for a weekend of sex, cake, and chicken—her attempt to win him back from his cult. Afterward, Anderson left and McKinney was arrested. The trial became a media circus, with the Daily Mirror publishing old nude photos and alleging that McKinney had worked as an S&M prostitute. She eventually jumped bail and fled the country. Great Britain made no attempt to extradite her.

The driving force behind all of Morris’s films is the quest to discover the truth. His motto might well be Jesus’s statement in John 18:37: “For this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth.” Upon closer examination, however, his working mantra actually seems more akin to Pilate’s terse rejoinder: “What is truth?” It’s perhaps fitting, for Morris’s world, that Jesus gives no recorded answer to that question. The truth is out there but is perhaps ultimately unattainable. On rare occasions—most notably in The Thin Blue Line (1988)—Morris arrives at definite conclusions; but generally, instead of giving answers, his films are about the questions, the quest. He examines his own incredulity, his desire to believe but his ultimate restraint. As Roger Ebert says, Morris’s films are always “about the intensity of his gaze.”Through his famous invention, the Interrotron—a two-way teleprompter that films his subjects from behind a video image of his own face—we stare not just through Morris’s lens but literally through his eyes. This makes the Interrotron more than a slick technological innovation: it becomes the symbol of his oeuvre’s raison d’être.

Does Tabloid measure up to this standard? It’s a lighter, frothier work than Morris’s past two films, Standard Operating Procedure (2008) and the Oscar-winning The Fog of War (2003), returning us to the discomfiting zaniness of titles like Gates of Heaven (1978) and Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control (1997). It also loses focus in the final third when it deals with McKinney’s later life. But it is as complex and probing as anything Morris has done. What is the truth behind Joyce McKinney’s story? What is a lie? And what is the difference? Speaking of her (alleged) lover’s (alleged) betrayal, at one point McKinney says, “You know, you can tell a lie long enough ’til you believe it.” It’s difficult, however, to determine just who exactly she’s talking about.

Unfortunately, however, the film ultimately fails in its examination of Mormonism. Kirk Anderson has sagely refused any public comment on the case, this film included, and hence Tabloid is left without an authentic voice for the Church.As a result, where every other aspect of the film is generally treated with a degree of nuance, the Church and its teachings are depicted throughout as myopic and ridiculous, its members as prejudiced, cruel, and utterly moronic for believing the cosmic bunk the Church puts out. The token expert is Troy Williams, identified on-screen as a former Mormon and gay activist. Despite his background and presumed ability to speak as intelligently about Mor monism as he does about McKinney’s story, Williams does nothing more than regurgitate tired anti-Mormon clichés like adherents’ belief that they can one day get their own planets. And Morris buys right into this: It is his voice, from off-screen, that first mentions “magic underwear,” and it was presumably his decision to incorporate animated footage from The God Makers to illustrate Mormon theology.

In entering the theater I did not expect glowing pro-Mormon propaganda. The story could not be fully told without probing Mormon beliefs on chastity and salvation, or even temple covenants and garments; McKinney reports that she and Anderson burned his as a symbolic gesture during their weekend together. But I did hope a filmmaker as thorough as Morris would seek out a genuine Mormon voice to help navigate those portions of the narrative. What is most intriguing about this omission is the fact that McKinney herself, who blames the Mormons and the wire services for ruining her life, seems to have more in common with the faith she reviles than she might care to admit. She easily uses Mormon vernacular like “Heavenly Father,” and her quest is actually quintessentially Mormon: She desires an eternal family. She repeatedly describes her relationship with Anderson as eternal; and when that plan is thwarted, she refuses any other husband and eventually turns her affection to her pets, especially her pit bull Booger. She describes in detail her attempts to keep her ailing dog alive; and when that failed, she turned to South Korean scientists, reportedly paying $25,000 to have the deceased Booger cloned into five puppies. Ultimately, she found a way to defeat death and extend her family, apparently eternally.

In the end, Tabloid is not a major work, but it comes from one of the world’s best documentarians and is a thrilling, hilarious, and thought-provoking film. Ultimately we are left to ponder the issues Morris wants us to ponder. The truth is out there somewhere; and though we may never attain it, it is the search, perhaps, that will set us free.

Errol Morris. Tabloid. Sundance Selects, Moxie Pictures, & Air Loom Enterprises, 2010. 87 min. Rated R for sex and nudity.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue