Articles/Essays – Volume 52, No. 4

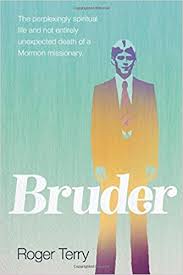

Rare as a Five-Legged Jackrabbit | Roger Terry, Bruder: The Perplexingly Spiritual Life and Not Entirely Unexpected Death of a Mormon Missionary

In November 1976, seventeen months into his Hamburg mission and 152 pages into his memoir about that mission, Bruder (i.e., Elder) Roger Terry and his companion bicycled into the German countryside, seeking a farmer who may or may not have given them an actual, real address. They parked their bikes next to a Mercedes, in front of a two-hundred-year-old thatched roof farmhouse attached to an even older barn. To their surprise, Hans Winter, the struggling farmer they met while street contacting, opened the door. The Mercedes, they later learned, had no engine because Hans only bought it to keep corporate farming conglomerates from bothering him with buyout offers. Even more surprising (to Bruder Terry), it turned out Hans was married to a Ghanaian woman named Juliet. Hans may have been a “typically German agnostic” and as “spiritual as a log,” but Juliet was spiritually alive, fascinated by these Mormon missionaries, and eager to learn more about their message. Juliet asked to meet again with some friends, a couple from Nigeria who were also seriously interested in the Mormon gospel. At this point, Terry had yet to baptize anyone, no serious investigators, and never met people so obviously interested, let alone willing to invite friends. Three willing investigators landed in Terry’s lap, yet he had no idea how to proceed. Again, this happened in 1976, two full years before the revelation that finally allowed people of color to participate in the priesthood. “Terry knew at once that his mission was about to get more interesting” (152).

Terry prefers the understatement. And writing in third-person.

Were this any other Mormon Missionary Memoir (or “MMM,” to borrow Terry’s abbreviation), I’d expect an immediate account of the aftermath of this meeting, what happened, when, where, who all got involved, and the inevitable resulting spiritual growth. But this is not that kind of book.

Bruder does masquerade as a typical MMM. For the most part, it moves chronologically, beginning with Terry’s childhood growing up in North Ogden, Utah, sheltered from the rest of the world and that “terrible decade that starred so regularly on TV newscasts,” the 1960s (6). Terry was an excellent athlete and student, but never thought about going on a mission until his sixteen-year-old girlfriend announced she would only marry an RM. At this point, he addresses one of the great paradoxes of growing up a Mormon Utahn. Although he “didn’t smoke, drink, do drugs, carouse, steal, lie (very often), cheat, sow wild oats, or swear (very loudly or in public),” he had never been very religious (7). Exploring this dichotomy, and the issues facing today’s Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is the book’s actual project.

Terry’s admittedly atypical MMM is clearly interested in toying with the genre itself and his approach to storytelling is truly postmodern. Drawing inspiration from Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut’s own semi-autobiographical novel set in Germany, Terry conflates storyteller, author, and main character. Bruder Terry’s experiences are written using a close third-person point of view, while present-day Terry frequently interjects with a first-person narrator in order to contextualize, philosophize, and question. Terry’s explanation for this approach is that he is not the same person as naive Bruder Terry, who saw the world as black and white, us vs. them. Forty years spent working as an editor of Liahona, Ensign, and eventually BYU Studies Quarterly allowed Terry to study Mormon history, sociology, culture, organization, economics, and theology. “There are certainly scholars who know a lot more about certain portions of the Mormon pie than I do, but there may not be very many who sample as many corners of the tart” (x). More importantly, present-day Terry is able to draw on this vast knowledge, put it in conversation with his mission experiences, and ask the tough (i.e., interesting and important) questions. Mentally, emotionally, and spiritually, the two Terrys are not the same person. Hence, the postmodern structure. I also suspect this approach accounts for the fairly spectacular subtitle. So it goes.

Typical to the genre, Bruder is organized by city and companion, reconstructed using journals, pilfered tracting books, and forty-year old memories. But where other memoirs proceed linearly, developing characters and locations at length and detail, Terry builds his narrative recursively. In order to approach the discussions he’s intent on having, and in order to ask the complicated questions he’s intent on asking, Terry addresses many smaller issues and many smaller questions, cycling back through characters and situations in turn. For example, before picking up the Juliet Winter thread again, Terry devotes a chapter to the birth and death of his complicated thirty-year relationship with Frau Sevier (the most beautiful and golden soul of his mission) and her boyfriend James (the darkest soul he ever encountered). By the time Bruder Terry finally asks his mission president for advice on how to have the priesthood discussion with Juliet and her friend Leon, and he’s told “Brother Terry, I’m just glad this is your problem and not mine,” we’re primed for a heavyweight and sincere discussion (171). And it’s in those moments, where present-day Terry describes how and why everything Bruder Terry “told Leon that day was not just offensive to Leon but to the Lord also” (171), that the book is at its most relevant and heartfelt best.

The effect of this narrative accretion culminates in Terry’s penultimate chapter “The Tongue of the Angels or the Mind of the Borg?” and afterword titled “Facing Reality.” Both of which I would recommend on their own to anyone remotely interested in A) stellar Star Trek analogies and B) a sincere, informed, and honest examination of the Church’s frustrating and perplexing structure and relationship to the contemporary world.

Now, instead of stealing any more of Terry’s thunder, how about some hilarious chapter titles? “J-Dubs [Jehovah’s Witnesses], DJ’s, and Breaking into Apartments,” “Dunking for Donny [Osmond],” and “Going to the Gynecologist.” I already said this wasn’t your typical MMM, which is why you need to read it.

Roger Terry. Bruder: The Perplexingly Spiritual Life and Not Entirely Unexpected Death of a Mormon Missionary. Salt Lake City: By Common Consent, 2019. 242 pp. Paper: $12.95. ISBN: 978-1-948218-10-8.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue