Articles/Essays – Volume 45, No. 1

Mapping Manifest Destiny: Lucile Cannon Bennion (1891–1966)

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

I don’t remember ever seeing my grandfather and grandmother together. I seem to remember a picture, him standing a foot taller than her, his face weathered. She wears her wide-brimmed gardening hat. But if it exists, I can’t find that picture. During my memory they lived apart. When I was very young she lived in her white, wood-framed house at Greenjacket, near Vernon, Utah, and he lived in his small box of a cabin at Riverbed, fifty miles westward in the desert. Was it her asthma that kept them separate or her desire to support the family with money she earned from selling her paintings? When asked, older relatives mention both reasons, but neither seems sufficient.

The effect for me has been that my grandparents represent opposites. I remember Grandpa—sunburned, whiskery, tall—standing in his irrigation boots at the edge of his alfalfa field. His cabin in the desert, inhabited only by men, held a pail for drinking water, a dirty and scarred table, and an ancient spring bed. The outside walls were tar-papered and there was not a decorative plant anywhere in sight. He was a writer and historian. Gradually he grew less mobile, sitting behind the stacks of historical articles and books about his bed, hobbling to the outhouse on his crutches. That cabin smelled powerfully of juniper smoke and of my grandfather, who never bathed so far as I knew. His main focus later in his life was making it as a rancher and most other considerations were plowed under.

Grandma was short, soft, and white, her face shaded by her wide hat. Her house had a garden, shade trees, beautiful yellow roses, and was surrounded by a tall woven wire fence with mesh to keep out rabbits. She was a painter and historian. Later she moved to an apartment in Salt Lake City.

The past few years I’ve been trying to look beyond their separation, their differences in faith and lifestyle, to see how they were alike. Although opposite in many ways, both my grandmother, Lucile Cannon Bennion, and grandfather, Glynn Sharp Bennion, responded with similar fervor to their dreams of pioneering and colonizing. Both admired explorers, those who searched westward for new land. My grandfather took up and abandoned seven ranches, moving farther and farther west. My grandmother painted adventurers—illuminated maps of explorers of new lands, including Abraham, the Vikings, Columbus, and trappers and fur traders. I admire both his ability as a hard-headed rancher and writer of history and her skill as a painter of detailed, complex maps.

My Bennion progenitors experienced the pull of Manifest Destiny as a religious mission. They felt that God had called them to settle the area around the Great Salt Lake. They weren’t the only settlers in the West to mingle religious and economic desire, but they were certainly among the most ardent. Under Brigham Young’s leadership, pioneers settled communities across the Great Basin, wherever they found sufficient water. Their cultivation of land helped fulfill the prophecy that the desert should “blossom as the rose.” My family’s love affair with the desert began with the first Bennions to come west and is renewed in succeeding generations. The protagonist of my novel Falling Toward Heaven embodies the male Bennions’ obsession with the western desert:

Howard could describe to Allison [his wife] or his mother his father’s desperation at the thought of selling land [or] Howard’s own lust to return, to raise up cattle and children in the desert, but it would be like describing color to the blind, or sickness to the healthy. . . . [L]and, sex, power, and God intermingled in every Rockwood male.

The powerful will in my ancestors and in other pioneers to expand land holdings was not entirely benign. Generally, westward migration displaced native peoples, and my own family moved into land in southern Rush Valley used by the Goshutes who had earlier befriended them. The western pioneers’ desire to skim the desert’s marginal bounty often damaged delicate ecosystems; my people allowed their livestock to overgraze land west of the Jordan River in the Salt Lake Valley and in Rush Valley. Often western women had to do without their men who were off ranching or farming; they have lived in poor lodgings and worked long hours in harsh circumstances. The women in my family birthed children midwinter without proper shelter, left lush, prosperous communities for the desert, and learned to deal with isolation from their own families.

Colonization is so difficult that those who succeed feel they must disregard the rights of those they conquer and sometimes also those who give them aid. In their stories and writings, these adventurers praise their own noble efforts, but rarely count all the costs. In my family, both men and women were affected by the impulse toward westward expansion, but in each generation they have responded differently.

Bennion men in my family manifested the romance of western expansion pragmatically and prosaically. My great-great-grandfather John expanded westward from his land in the Salt Lake Valley, Israel organized a community closer to the water, and my grandfather, Lucile’s husband, ran a series of ranches as he homesteaded westward. They believed that pioneering the wilderness was a heroic act, universally beneficial. They assumed that a well-managed garden, field, pasture, or range manifests an aesthetic, economic, and philosophical beauty. In making such a thing, organizing the undeveloped land, they believed they participated with God in the work of creation as the artist does in making art: a bodying forth.

I believe that my grandfather’s love of a well-ordered field is connected to my grandmother’s love of painting maps. Both involve the aesthetic and practical creation of a good thing. She believed that writing history, or drawing it, brought a useful object into existence. In a letter to my father, she described her husband’s efforts at historical writing:

Your father has just completed a very excellent article on Brigham Young and Jim Bridger. . . . It really is very, very fine. He is all the time gaining in ability to see, to analyse and to express with conviction the wonderful things he finds in the files of the Historian’s Office. I feel too that he has gained this winter a new view of Brigham Young’s work which will be helpful to him, to us and to others who read his findings.

Here she demonstrates her belief that a body of knowledge can be a worthwhile creation, perhaps even more important than a ditch bearing water or a tall field of alfalfa. In her illuminated maps, she chose as subjects men who followed, like her husband and his fathers, the exploring and pioneering impulses. She portrayed them with romantic idealism, as heroic colonizing figures.

My grandmother was born in 1891 and died in 1966. In addition to her labor raising my father Colin and his four siblings, she worked as a teacher and an artist. My earliest memories of her have to do with her efforts to stimulate my imagination. Several times one summer, she led me across the hill behind her house at Greenjacket near the small town of Vernon in western Utah where she showed me a pathway through the junipers that she called the fairy tunnel. There was a ring of junipers where she said the deer council met at night. I imagined the bucks, huge as Bambi’s father, standing inside the circle.

Her house, with a western porch and exterior pine boards, painted white, was surrounded by rose bushes, which produced a small yellow flower. We thought for many years that these flowers had died off, but apparently they go dormant in drought, because in the recent past they have grown back around the house, now inhabited by my sister.

The house still has lovely maple floors; dark wood frames the windows. I have made this house the setting of a novel and several short stories; truth and fiction mingle in my head.

Grandma kept her paints and brushes inside a lacquered Chinese cabinet. She owned a toy Viking ship, made of brown plastic; it sits in my closet now with its cream-colored sail and tiny brown men wielding the movable oars. I remember an easel with a painting, which I wasn’t allowed to touch, set up in her living room.

A copy of her painting, Abraham: Friend of God, Prince among Early Peoples (1958, tempera, 35″ x 60″)was reproduced by the LDS Church for use in Sunday School lessons. I’ve seen a copy in the LDS Church Library in Salt Lake. It shows Abraham in the center with angels in ranks to the left and the right. The angels extend their arms and bow their heads toward him. The circle in which he stands is violet, with a swirl of blue and white below, as if he stands above the curve of the earth. Scriptures from Genesis and the Book of Abraham are inscribed below his feet.

The background maps the lands Abraham wandered, the area bounded by the Mediterranean Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Caspian Sea. To Abraham’s right is Canaan, to his left Ur of the Chaldees. Sailing ships float on the three seas. Small images of Greek, Roman, and Assyrian statuary and Egyptian paintings ornament the map. To the left and right are twelve smaller images titled Canaanite Captives, Felling the Cedars of Lebanon, Semite and Nubian Captives, Measuring and Recording the Harvest, Egyptian Funeral Rites, Syrians Bring Tribute to Pharaoh, Tribute to Nanar, the Moon God, Assyrian Lion Hunt, Scribes Record Plunder, Goldsmiths’ Work at Ur, Sumerian Archers, and Babylonian Two-Winged God.

In creating a map of his physical travels, my grandmother emphasizes Abraham as an explorer and colonizer rather his more common identity as a man of God. For Abraham, moving on and living a righteous life intertwined. The Pearl of Great Price, part of the LDS canon, says that Abraham left the land of his father in order to “be a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge, and to be a father of many nations, a prince of peace.”He wishes to “obtain another place of residence”—certainly for spiritual advancement (to have greater dominion in the eyes of God), but also for economic benefit. My grandmother read in this Old Testament prophet’s life an ideology very close to what the men in my family believed. In fact, she simply painted an ideal narrative that persists today: that the Mormon pioneers follow the pattern of Abraham in their colonizing efforts. She writes in small letters on the painting:

Born among a sinful, idolatrous people, Abraham yet maintained faith in the living God to become his chosen instrument, through whose ministry God’s name should be known in the earth forever. Revered by Christian, Jew, and Mohammedan, he was priest, patriarch, prince of peace, exalted father of many nations; faithful, just, steadfast in righteousness, possessor of great knowledge, through whom all nations of the earth should be blessed.

Both her father-in-law Israel and his father John believed a similar ideology—that those who explored new lands were strong, vital, righteous men. My grandfather Glynn was more of a realist in terms of his historical essays, which showed the cruelty of whites toward the native residents and the carelessness with which they overused the land. Still, he thought of his own enterprises as driven by idealism and when he stopped believing in the LDS Church, he clung to a secular version of that dream.

God promised Canaan to Abram. Apparently Abram didn’t have to fight for the land or force anyone out, something unusual for colonizers. The Bible does not record any strife as Abram’s herds multiply in their new home, except that between the servants of Abram and Lot. His battles are defensive: when Lot is captured by the invading Kings of Mesopotamia, Abram takes an army to retrieve his nephew. Earlier, when he was worried that Pharaoh would murder him in order to marry Sarai, he chose to avoid trouble by lying. While Abraham may seem less violent than many other colonizers, he was ready to sacrifice his son in obedience to God’s command. It seems probable that fulfilling God’s desire to move his herds and family to Canaan would have outweighed all other considerations. This is a common trait of many of the subjects of Lucile’s paintings, that their highest priority is moving into the new land. Their ethical and religious systems are often reshaped to support this end.

Another of Lucile’s maps, The Vikings (1936, tempera, 24″ x 41″),hangs in the hall of my home. She painted light blue for the ocean, beige for the land, with a rim of dark blue defining the boundary between. The map shows the Americas to the left, Greenland upper center, and Europe and Asia to the right. Ships are the most prominent feature—striped sails decorated with images: a rising sun, rearing horse, or long-tailed dragon. These vessels stream from left to right, showing the movement of colonization outward from Norway to the Baltic Sea, the Gulf of Finland, and to an inland Lake Ladoga inside present-day Russia. Ships also stream southward to England through the Irish Sea, past the coast of Portugal, eastward through the Straits of Gibraltar, across the Mediterranean Sea, past Istanbul, and into the Black Sea. Westward the ships pass Iceland, sailing up between the coasts of Newfoundland and Greenland.

Viking figures stand in Europe, Greenland, Iceland, and the eastern coast of America. On the St. Lawrence River floats an Indian canoe. An old Viking warrior/settler stands on Nova Scotia, leaning on his long ax. In the same locale are a lodge and a figure resting on a bier, curved like a ship. A young Viking raises a horn of mead. A horseman rides across Norway. In southern England, a warrior facing an invisible enemy holds his shield before him and raises his sword behind his head, ready to deliver the death blow. She didn’t paint the face of the man he was attacking. A trader standing on Turkey offers furs to a Middle Eastern merch- ant.

Around the border are twenty-eight small inset sketches that alternate between Norse poetry and descriptions. The sketches show Odin, Thor, the Valkyries, the Skalds or singers of the sagas, Niflheim or hell, a dragon ship on a wild sea, and the northern lights. Lucile wrote, “All men who have fallen in fight since the beginning of the world are gone to Odin in Valhalla.”The phrase appears to express something close to what she seems to feel toward their heroic nature as explorers and colonizers. Below the drawing of Valhalla is the following poem, taken from the Sayings of Grímnir in the Poetic Edda and inscribed by my grandmother:

Gladsheim

in Du Chaiilu

is the fifth called

Where the gleaming

Valhalla stands;

There Odin

chooses

EverydayWeapon-dead men.

That hall is very

Easily known to those

Who

come to Odin;The hall is roofed with shafts;

It is thatched with shields;

Benches

are strewn with armor.That hall is very

Easily known to those

Who come to Odin;

A wolf hangs

West of the door;

An eagle hovers above it.Five hundred doors

And forty more

I think are in Valhalla;

Eight hundred warriors

Go through a door at once

When they go to fight the wolf.

Theirs was not the righteous and peaceful colonization of Abraham. By inscribing this poem onto her painting, my grandmother gives colonizers the status of warriors. Elsewhere on the map, she is more specific about the traits she admires in the Vi kings. Next to a picture of a fjord, she wrote: “The small farms of Scandinavia, separated by mountain and fjord, too poor to support a feudal castle, bred a race of proud, freedom-loving men, whose descendants fought tyranny in England and America.” A scroll under the central figure on the map contains her description of the values of the Vikings:

The sagas reveal a magnanimous quality in the Vikings, for the contests therein glorified had to be equal, chief against chief, ship against ship. From this sporting spirit, which included a religious zest for daring enterprise and fierce retaliation for wrong, may be traced to the chivalry of medieval Europe. The Vikings were more than pirates. A mature nobility, a magnificent daring, a power to lead, to organize, to establish a better order of things, made them the master spirit of their age. Independent, just, imaginative, ruled by the heroic tenets of their virile religion, they developed the spiritual elements from which have sprung the institutions of free government.

My grandmother thus endows the Viking wanderings with a romance similar to that described by my male ancestors as they wrote about the settlement of the West. She eliminates references to the Vikings’ savagery, their acts of plunder and destruction against those they conquered. She makes no mention of the British men they slaughtered or the women they raped. The destruction of monasteries with their priceless manuscripts is invisible to her. She single-mindedly describes an idealized version of their conquest. Of course, she likely responded to the historians of her time, who painted the Vikings as romantic adventurers.

A third painting, Columbus (1938, tempera, 15″x11″),is divided horizontally into two parts by the following text: “Born in obscurity, unhonored in death, Columbus yet made the greatest discovery of all time. Sustained through peril and strife by his glorious visions he held to his purpose and won the undying gratitude of mankind.”My grandmother thus situates him in the same heroic group as Abraham and the Vikings. In the upper half of the painting, Columbus stands slightly off center to the right, a sail behind him. He extends his arm toward the sea. Above him is a swirl of clouds containing images of the Far East, where he imagined his voyage of discovery would end. Smaller images surround the main scene—a dragon, Spanish monks and warriors, the Statue of Liberty. With this image my grandmother suggests that his voyage paved the way for all those who left Europe for America where they could search westward for their own land. She could have also drawn in a few Mormon pioneers, who believed that Columbus was divinely inspired to prepare the way for the establishment of Zion on the American continent. Below the text she has painted the Atlantic Ocean; white lines record Columbus’s various voyages between the Old and New Worlds.

As in her portrayal of the Vikings, my grandmother focuses on Columbus’s visionary nature, his bravery and determination. She focuses on his positive achievements and neglects the fact that he kidnapped, enslaved, and killed local peoples. He refused to baptize many natives because that would cause problems for the potential slave trade: Catholic law forbade the enslavement of Christians. Perhaps his most significant act in clearing the New World for Spanish colonization was accidental: the introduction of smallpox to the natives brought the death of millions.

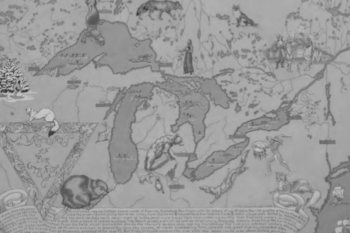

A fourth painting, Trappers (1934, tempera, 18″x23″),centers on the Great Lakes, which looks like a cluster of fallen leaves. Surrounding the lobes of the lakes are images of animals: mink, otter, beaver, fox, wolf. Canoes cross the lakes; trappers and Indians meet to the right of the canvas. An Indian leans forward in a battle stance, shield extended, arm raised to strike with an ax. A scroll across the bottom of the painting reads:

For more than 150 years the Great Lakes region, richest beaver lands of America, furnished New France with its sinews of war & peace. The rich profits of the fur trade & the free adventurous life in the wilds lured the most vigorous young men of the colony from the farms & likewise the Indian from his fields & useful village arts. Suited by temperament to pioneer the trade, the dashing coureurs were never more at home, never more happy than when paddling swiftly over the cold waters or passing noiselessly along ancient forest trails with a band of Indian hunters. The Jesuit priest, patriot as well as missionary, zealously aided in diverting the fur trade from Dutch & English rivals to Montreal. From the forts which dotted the shores the coureurs-de-bois each spring rounded up the Indians with their winter’s stock of furs for the grand rendezvous at Michiliinackinac or Green’s Bay. Here the canoes, at times numbering 400, joined in one great flotilla, proceeded down the Lakes to the annual fair at Montreal, greatest of fur marts. But if the Iroquois were on the war path the lake route was abandoned, portage made & the journey continued by way of the Mattawa & Ottawa rivers.

These images portray the nobility of men who explored the world, moving west to open new lands. For Lucile the most heroic men are those who leave civilization, a mingling of Manifest Destiny and an odd theory of survival of the fittest. To the best men went the rewards of the new lands. In reality those men were generally violent misfits, those who refused or were unable to accept the civilized manner of Eastern cities. They raped native women, stole from each other, became drunken and violent when they gathered, and slaughtered millions of animals for their pelts. Perhaps they valued independence, but this was often translated into antisocial behavior.

In The Big Sky,A. B. Guthrie describes the lives of trappers, who were as savage individually as the Vikings and the Spaniards were collectively. Their story is tragic because they cleared the way for farmers and colonizers who civilized the wilderness the trappers loved. They created the conditions that eliminated their own lifestyle.

While I have a more cynical attitude toward the land fever that made my ancestors see the desert wilderness as a potential field or garden, my grandmother had a romantic vision in which charting wilderness made way for human communities. I don’t know that the cruelty of these people was invisible to her, but she didn’t paint cruelty. She used her paintings to teach a specific vision of the history of westward expansion, participating in the creation of an ideology that fused ideals borrowed from Hebraic, Viking, and European traditions. Through these four maps and many others she portrays acts of exploration and colonization as heroic, as embodying the highest cultural virtues of courage, freedom, ambition, and community.

Maybe she didn’t share our modern, liberal sensitivity to the violence of these early colonizers. To me she was a kind and gentle woman. In fact, she was so calm and her art is so persuasive that I didn’t even recognize that she was telling only half the story until friends in my reading group pointed out the irony of noble Vi kings, a heroic Columbus, and civilizing trappers. Certainly violence was a part of the lives of the English and French trappers, the Spaniards, the Vikings, and the Hebrews. The Mountain Meadows Massacre, the Bear River Massacre, the Battle of Provo River, and the many stories of cruelty against the Goshutes offend my peaceable nature. But it may not be accurate to say that those who lived in times when such violence was invisible and accepted were not good people. It’s apparent that violence as a means to settle conflict was broadly accepted throughout most of the history of the world.

In her short story, “Where Nothing Is Long Ago,”Virginia Sorensen describes a water killing in a turn-of-the century Mormon village. The story suggests that while we as a modern people presume to abhor violence, the reality is that it isn’t that far back in our pasts. In fact, it’s clear that violence hasn’t passed: it remains present in all our lives. It is legal to execute a man for murder in my home state of Utah—an act straight out of the Old Testament law of Moses. We pay boxers and football players millions to attack each other. We have cities with areas where police don’t enter because they would be killed.

I guess what finally causes me the most curiosity about my grandmother is that she doesn’t reference any of this violence. It’s as if it didn’t happen for her. I was a child when she died, and now I long to speak to her, to discover what she thought, to have her tell me why she painted as she did. Even then, I believe my admiration for her will remain strong. She seems to me to embody the nobility she tried to paint.

My grandfather often told me the story of one of her painting expeditions. She drove west toward his homestead and stopped the car in the middle of the wide desert plain just to the south of the present-day Dugway Proving Grounds. She climbed to the top of a bluff, braving any rattlesnakes hidden in the shadows of the boulders. On top she found the vista she had sought as the gray buttes, mountains, and flats spread around her. She set up her easel and started painting. That is how I want to remember her, on top of that bluff, facing west as she sketched the desert.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue