Articles/Essays – Volume 43, No. 3

Light in Darkness: Embracing the Opportunity of Climate Change

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

“I howl like a wolf and mourn like an owl.” (Micah 1:8)

Some readers of this article may know me as an environmental activist (my version of public and church service). A few may know me as an outdoor photographer (my day job). But here I’d like to put on another of my hats. Long before I took up cameras and activism, I was a student of the ancient Near East, with a special interest in Israel and the Bible. In this article, I propose to turn exegete once again and examine the biblical notion of Zion as a model for sustainable living in a world threatened on many fronts by the consequences of its own success. I do this with an appreciation of the irony involved, for Bible study was, at least indirectly, the beginning of the end of my active involvement in organized religion. However, in part because of that crumbling of belief, my Bible study was the start of everything good that has followed, including the photography and the activism. What’s more, although I now approach the Bible very differently than I did as a Mormon missionary thirty years ago, the Bible is, if anything, more significant to me now. For me, as I hope for readers of Dialogue, it remains a foundational cultural and spiritual document.

I begin, however, with a proposition that would seem to be far removed from the Bible and its concerns. Indeed, my proposition would seem to be at odds with typical notions of what religion is all about. My proposition is that the issue that should be at the top of our agenda isn’t the defense of marriage, it isn’t “values,” it isn’t abortion. It isn’t states’ rights or the danger of socialism or Obamacare or any of the things that now preoccupy our neurotic, values-obsessed, and values-poor society. The central problem of our time is climate change, in comparison to which all other issues, even legitimate ones, shrink to insignificance. Climate change is the problem of problems. It is the ecological problem, the social and economic problem, the health problem, and the moral problem—and not just of our time but of all time.

My proposition has an equally odd-sounding correlate: that churches have a uniquely important role to play in addressing this problem of problems. Indeed, it is in addressing this problem, I contend, that churches will find a moral purpose and a relevance that they have lacked now for many years. In the case of the LDS Church in particular, I believe that it is in embracing the opportunity for personal and societal transformation represented by climate change that we will rediscover Zion. Indeed, I would go further: the future material and spiritual success of the Church are tied, for better or worse, to how we respond to climate change, which is both litmus test and potential catalyst, stumbling block and keystone. Climate change is, for our time, what the political crisis of Isaiah’s and Jeremiah’s time was for ancient Israel: the ultimate moment of truth. With this preamble, I’d like now to consider what light the Bible, “that book so little read in so many places at so many times” (Thomas Greene), might shed on this issue for religious institutions that, in theory if not always in deed, honor the Bible as a foundational document.

Arise, shine, for thy light has come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee.

For, behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and gross darkness the people: but the Lord shall arise upon thee, and his glory shall be seen upon thee.

And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising. (Isa. 60:1–3 KJV)

The speaker of these words called himself Yesha‘yahu, or Isaiah, and was the second or third of Israel’s prophets to use that name. He wrote at the end of the biblical period and, as one of the last of the writers of the Bible, could look back over hundreds of years of thought and action inspired by Israel’s unique faith. As one of the last of its prophets, he saw himself and his people at a turning point when at last the promise of God’s covenant with Israel would be mutually fulfilled.

If the Bible has a red thread, an organizing principle, it is certainly the concept of the covenant. What does this covenant mean? To understand, we must go back to the beginning of Israel’s history, as Israel’s priests did when they were putting the Torah in its present form. For them, the story began with God’s creation of humankind, “Let us make mankind in our image, according to our likeness” (Gen. 1:26). For Israel’s priests, the resemblance between God and human beings was both physical and spiritual. It was this resemblance that made it possible for God at a later date to tell Israel, “Holy you shall be, because I, Yahweh, your God, am holy” (Lev. 19:2). Without such a resemblance, such a requirement would be impossible. But even at the beginning of history, before ever saying a word to this effect, God expected people to model their behavior on His.

They didn’t. God’s first attempt to create a holy following failed. The descendants of Adam and Eve created a world filled with violence. Clearly, if people were going to become holy, God would have to do something more than simply turning them loose on their own recognizance. And so, after wiping out all life on earth except the beings saved in the ark, God gave humankind its first instructions on how to behave. He told Noah that people may not kill each other because they are the image of God. And He told Noah that, while people would now be allowed to eat animals as opposed to just plants for food, the life of these animals, as represented in their blood, belonged to God and to God alone.

This was the first simple statement of ethics and the first dietary law of the Bible (Gen. 9:3–6). Once more, however, humanity failed to live up to its promise and its obligation. Human beings again filled the earth with violence and even proposed to take heaven by storm by building a gigantic siege tower (Isa. 14:13–14: Babel and Babylon, the same city at different ends of history, define arrogance). God responded by scattering humanity to the winds and making it difficult for them to work together. Students of foreign languages will be forever grateful for this difficulty.

And so God made a third attempt. Again He singled out one good man and made him a promise that He had not made with Noah or with Adam. God bound Himself to this man as a friend, with the promise that He would be a friend not only to the man but also to his offspring. In time, God took the descendants of His friend, Abraham, and set them down at the foot of Sinai for a lecture like no other in history. In painstaking and unprecedented detail, God laid out for the Israelites what it means to be holy. No aspect of life was too trivial for consideration. Diet, clothing, hygiene, behavior, governance—God spelled it all out for them so that there would be no room for excuses. This was Israel’s Torah, the Teaching, the basis for the agreement between God and His people. If they would follow His Teaching and become a holy people, He would be their God and would dwell among them—literally. In Israelite thought, the giving of the Torah and the covenant at Sinai are the epitome of God’s relations with humankind, for at Sinai God at last gave human beings the knowledge of how to become like God.

Such is the vision of the Torah. But the biblical story of God’s passionate involvement in the life of Israel of course does not end there. It continues in the prophets, whose theme is the failure of Israel to live up to this covenant responsibility. The tone of the prophetic message down the ages is set by Samuel, the first great prophet after Moses of whom we have any substantial record. Samuel rebukes Israel for its desire to have a king like the other nations, for Yahweh was its proper king (1 Sam. 8:10–22). Samuel also rebukes Saul, Israel’s first king, for having saved some of the spoils of battle to make a grand sacrificial offering, despite Yahweh’s command to destroy them. Samuel’s response to Saul will echo through generations of prophecy, “Does Yahweh desire whole offerings and sacrifices as he desires that you hear him? To hear is better than sacrifice, and to listen better than the fat of rams” (1 Sam. 15:22).If king and priest were the anointed executors of the divine will, the prophets were the guardians of it, a role that from the beginning put them at odds with the political and religious establishment. “So these men, the prophets, who mostly have no appointment but only a mission . . . stand and summon to justice the representatives on the royal throne for their treachery against YHVH and His commandments,” wrote Martin Buber. “One after another they repeat God’s words, ‘I have anointed thee to be melekh,’ or ‘I have appointed thee nagid’: Samuel to Saul (1 Sam. 15:17), Nathan to David (2 Sam. 12:7), Ahijah to Jeroboam (1 Kgs. 14:7). For four hundred years, they come one after the other and take their stand before the prince and reprove him because of the violated covenant, and finally Jeremiah (22:6ff), sometime after the disaster [the fall of Jerusalem], announces destruction for the king’s house which had not been just, and therefore was no more justified.”

The conflict is tragic and deeply moving, as in the case of David, who is Yahweh’s champion in war and a charismatic figure of enormous human depth and obvious faith. Even David, who, like Abraham, was promised that his dynasty would enjoy God’s special favor forever (2 Sam. 7:16) and who was the model for and progenitor of the Messiah, does not escape prophetic censure. In contemporary pagan literature, kings were the subject of epic and hagiography. In Israel, they are the foils of the prophets, cautionary tales of the failure of even the greatest to live up to their responsibility. It’s an extraordinary tale, without parallel in world literature, which perhaps is why many people today still read it, long after the royal propaganda has been relegated to the dustbin. I wonder, though, how many readers understand its message. No book in history sits less comfortably with the status quo than the book that has so widely become the icon of the status quo.

In the end, what the prophets look for and universally fail to find is the transformation of a people. In the view of the prophets, it is precisely the Lord’s chosen people who are the most blind and deaf to God (Isa. 42:19–20, 43:8; Jer. 5:21, 6:10; Ezek. 12:2. See also Isa. 30:9; Jer. 6:17; Hos. 4:6, 16; 7:11), who do not understand God (Hos. 4:1 || lack of covenant loyalty; 4:6 || forgetting the To rah; Isa. 5:13; Jer. 22:16–17), and who are unclean (Isa. 64:6). The prophets therefore seek a national purification, a return to funda mental principles. In Hebrew to this day, the word for repentance is simply “return,” teshuvah. Jeremiah tells Jerusalem, “Wash your heart of evil (kabbesî mera‘ah libbeka) that you may be saved” (Jer. 4:14). “Circumcise yourself to the Lord, remove the foreskin of your hearts” (Jer. 4:4) so that you become in fact as well as in belief a holy people (Amos 5:14; Isa. 62:12; see also Jer. 2:3; Isa. 6:13).

The apparent resistance of the people to deep, wholesale, and permanent transformation provokes the prophets to anger and sorrow, for they see, as the people do not, the disparity between what is and what could be, and between what is and what must be. In reality, the Israel of the prophets was probably not, for the most part, a society run amok, prophetic indictments notwithstanding, but an everyday kind of society with its “normal measure of daily sin.”Hezekiah (715–687 BCE) and Josiah (640–609 BCE), for example, ruled for almost sixty years between them during a century of exceptional political turbulence and social change. Such longevity itself says something about the likely quality of their leadership. The Bible recognizes that they were, in fact, good kings who generally did right by God and by the people. Of Hezekiah, the author of 2 Kings says, “In Yahweh, the God of Israel, he put his trust. . . . There was nobody like him among all the kings of Judah who succeeded him or who had gone before him” (2 Kgs. 18:5). Josiah “did what was right in the eyes of the Yahweh, following in the footsteps of David, his ancestor, and deviating neither to the right nor to the left” (2 Kgs. 22:2). Jeremiah himself says of Josiah that “he upheld the cause of the lowly and the poor” (Jer. 22:15). And yet, it is during this same period that Isaiah and Jeremiah thunder against Israel, because there were also less-than-exemplary kings, less-than exemplary ruling classes, and even less-than-exemplary poor. Jeremiah blankets them all with furious denunciation, “From the smallest to the greatest of them, all seek gain, from prophet to priest all deal falsely” (Jer. 6:13, 8:10).

In an ordinary society, notes Abraham Heschel, one of the greatest Jewish interpreters of the prophets, “Few are guilty, but all are responsible. . . . In a community not indifferent to suffering, uncompromisingly impatient with cruelty and falsehood, continually concerned for God and every man, crime would be in frequent rather than common.”Israel had crime, and corruption, and poverty even at the best of times, like all societies before and since. But for a people under covenant to be holy, being ordinary—being like every other nation—was to fail God. The fact that crime and corruption and all of the ills of normal society had not disappeared demonstrated to the prophets that Israel’s commitment to the covenant was insufficient. In the end, while the prophets produced a long litany of the people’s offenses, what they really condemned Israel for was being ordinary.

The importance of this point cannot be overstated. Believing readers of the Bible today who suppose that Israel was punished because it was in fact unusually wicked fundamentally miss the point, which is that the Israelites were probably just like most people in most ages, and the prophets condemned them. The prophets were not sociologists or moral statisticians. Their indictment of Israel was not compiled from an encyclopedic knowledge of the people’s sins but rather from the observation of Israel as a whole and its self-evident failure to be something radically different. The prophetic indictment was therefore not subject to mitigation by the righteousness of some individuals. The prophets were no more concerned with individual righteousness than with individual wickedness. Of course individuals must be righteous. But if society as a whole cannot rise to the challenge, individual righteousness does not matter. The righteous and the wicked perish together. “To a person endowed with prophetic sight,” Heschel continues, “everyone appears blind; to a person whose ear perceives God’s voice, everyone else appears deaf. No one is just; no knowing is strong enough, no trust complete enough. The prophet hates the approximate, he shuns the middle of the road. . . . The prophet disdains those for whom God’s presence is comfort and security; to him, it is a challenge, an incessant demand. . . . The prophet’s word is a scream in the night. While the world is at ease and asleep, the prophet feels the blast from heaven.”

For the prophets, the transformation of the world—and their ultimate vision is of a transformed world modeled on Israel’s holiness (Isa. 2:2–4, 42:6–7, 45:22, 49:6, 56:6–7, 66:18–22; Mic. 4:2; Jer. 3:17, 4:2, 12:16, 16:19; Zeph. 3:9–10; Zech. 2:15, 8:20–23; 14:16–21)—requires, first, that God’s people take their divine mission to heart in a way that they have not yet done. Israel is the first fruits of God’s harvest of the nations (Jer. 2:3). Thus, after chastising Israel for its failure to embrace its mission, God tells Jeremiah, “I will put my teaching (torah) inside them and write it on their heart, and I shall be their God and they shall be my people” (Jer. 31:33). In this last chapter in the story of God’s relations with hu mankind, “they shall no longer teach each other, man and neighbor and man and brother, to ‘Know the Lord,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest” (v. 34). Bringing the story full circle, Jeremiah reminds his people that the person telling them this is “the Lord, who gives the sun to light the day . . . and who ordains the moon and the stars to light the night” (v. 35). Only at this point can God say of humankind, “It is good.”

The essence of biblical prophecy is not to see what will be but to see what is and what can be. The reality that the prophets saw is that, while the physical universe is all that God intended it to be, God’s masterpiece, humanity, “is still in the process of being created.”And what God hopes to achieve with this part of His creation is an image of Himself. While God prohibits icons to Israel, He permits Himself one: Israel is God’s icon. Israel is God’s mate, His love, His passion. According to the Bible, God intends to create a nation that embodies His own holiness, His own righteousness. Thus, Isaiah in a striking image says, “But the Lord of hosts shall be exalted in justice, the Holy One of Israel sanctified in righteousness” (5:16). It is not in His omnipotence or His omniscience that God says He is distinguished, but in His righteousness. Omnipotence and omniscience are qualities that uniquely characterize God, yet in Isaiah’s vision these qualities are not what God chooses to dwell on. Rather, it is the quality that He shares with His human creation.

What God seeks in humankind is the same overflowing of righteousness that exists within Himself, that seeks to fill and to transform the world. “Let justice flow like water, and righteousness like a stream” (Amos 5:24).This righteousness is an irresistible, positive force, not the static balancing of interests or the maintenance of “law and order” that we associate with justice. In real-world justice and law and order, there are many ways, especially for the powerful, as the prophets knew only too well, to side-step responsibility. Even in the midst of social order, therefore, in justice and inequity abound. Righteousness does not tolerate such a status quo. It seeks constantly to redeem the imperfect. “It is by justice that Zion shall be redeemed, and by righteousness her inhabitants” (Isa. 1:27). And the scope of the intended redemption is universal: government, religious life, and civil life as well as individual behavior must all be transformed.

As Amos’s metaphor illustrates, justice and righteousness in prophetic thinking are not principles that exist in the abstract. They are not morals or ethics but the force of goodness in action that emanates from God to human beings. In fact, they are important ultimately because—and only because—they bless human life, for God Himself seeks fulfillment in human beings. Injustice, too, is a force that flows in the other direction. Thus, “injustice is condemned,” observes Heschel, “not because the law is broken, but because a person has been hurt,”and God, too, feels that hurt. “You shall not afflict any widow or orphan. If you do afflict them, and they cry out to me, I will surely hear their cry . . . I will hear, for I am compassionate” (Ex. 22:22–23, 27).Or as Jesus would later stress: Inasmuch as you do it to the least of these, you do it to me (Matt. 25:40).

There is no more profound expression of the human aspiration for goodness. Nor is there a more tragic appreciation of human reality, which expresses itself in the prophets as divine pathos. In nothing are the prophets as moving as in their sense of the disjunction between God’s desire to touch His people’s hearts and their unwillingness to be touched. “My land, my land, my land,” cries Jeremiah (22:29).

Go up and down the streets of Jerusalem. . . . Can you find anyone who acts justly, anyone who seeks the truth, that I may forgive that city? People may swear by the life of the Lord, but in fact they perjure themselves. Lord . . . you punished them, but they took no heed; you pierced them to the heart, but they refused to listen. They made their faces harder than flint; they refused to repent. I said, “After all, these are the poor, these are folk without understanding, who do not know the way of the Lord . . . I shall go to the great ones and speak with them; for they will know the way of the Lord. . . . ” But they too have broken the yoke and snapped their traces. (Jer. 5:1–5; NEB)

What the prophets hold out to Israel and see refused is the prospect of abundant life (see esp. Isa. 55). As Moses says at the beginning of Israelite history, “Life and death I have set before you, and blessing and cursing. Choose life” (Deut. 30:19; see also Amos 5:5–6). What Moses and his successors hold out is not simply a way of life that avoids imminent, nasty death. It is not a stay of execution. It is rather a blessing, a life of unimaginable possibility and radical freedom empowered by the presence of God Himself. Yet Israel, in the prophetic view, refuses it.

For the prophets, as Heschel observes, “The opposite of freedom is not determinism [an inability to act freely], but hardness of heart [a refusal to act rightly]. Freedom presupposes openness of heart, of mind, of eye and ear. . . . Hardening of the heart is the suspension of freedom. Sin becomes compulsory and self-destructive. Guilt and punishment become one.”Freedom is therefore more than the simple possibility of self-determination. It is the active opposite of all those qualities that characterize Israel in its refusal to be touched: stubbornness, hardness, and brazenness of heart (Deut. 29:18; Lam. 3:65; Ezek. 2:4), the willful refusal to see and hear reality (Isa. 42:19–20, 43:8; Jer. 5:21, 6:10; Ezek. 12:2; see also Isa. 30:9; Jer. 6:17; Hos. 4:6, 16, 7:11). To be free is to become all that one can become, not simply to make one’s way with God knows how many shackles holding you back (Isa. 5:18).

Despite their sorrow at Israel’s present rejection of freedom, the prophets to a man hold out the possibility that at some point things will change and Israel will at last embrace its mission. If the present scene is bleak, the ultimate outcome is a happy one. How could it be otherwise? If Israel’s refusal to become the image of God were to be the last word, then God’s creative purpose would come to nothing. By definition, such a frustration of creation cannot happen. Confidence in the human capacity to repent saves the prophets from despair.

Such is the paradigmatic, biblical story of God and his people from the creation to the fulfillment of creation in Zion. In the thinking of the Bible, the unity of God and His people at the end of time is what will inspire the rest of the world, the nations and their kings, to come knocking on Israel’s door in search of the same blessing. This is the biblical paradigm of Zion, the kingdom of God, the exemplary city on the hill that brings about the final transformation of humanity into the true image of God. This is the essential, unifying message of the Bible throughout its long history.

This is therefore the theme that Jesus, too, comes preaching. “Now after that John the Baptist was put in prison, Jesus came into Galilee preaching the gospel of the kingdom of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand: repent ye, and believe the gospel’” (Mark 1:14–15; KJV). Jesus’s gospel wasn’t new. He didn’t need to explain the kingdom to his fellow Jews, because they already knew what it meant. The gospel, the good news of Jesus of Nazareth, is the old priestly and prophetic ideal of the holy nation, the Zion society, that is built upon the premise that men and women are under a divine injunction to be holy, to realize in themselves the divine likeness that is theirs in potentia. In the Gospels, this ideal is personified in Jesus. It is an inner, individual reality, as all righteousness must be. Jesus’s whole moral teaching underscores this point. But it is also a collective truth. For Jesus, or any other individual, to be the sole, essential, or isolated embodiment of the ideal renders the notion of a “kingdom” meaningless. Thus, Jesus can say, “The kingdom of God is entos hymon” (Luke 17:21) and mean both “among” and “within you.”To live up to this injunction is the biblical value.

There is in all of this long story of the Bible an astonishing integrity, as of a man’s life that makes sense as he looks back on it in old age. Although what we now call the Bible, the so-called Old and New Testaments, was written by many hands over many centuries, it has meaning as a whole that unites the many disparate and not always mutually consistent parts. The same can be said of the history of “God’s people” after the Bible. The Zion idea reaches into the Christian tradition of monasticism, which likewise sought to create a community of holiness that linked the mundane aspects of life with the spiritual quest. The Zion idea is in part the inspiration for the Puritan tradition and, through it, for not a little of the American religious experience, whose most extraordinary manifestation is the religion of the Latter-day Saints.

It was this ideal that brought my ancestors here to the Great Basin 150 years ago in what they believed was the end of time, the “latter days,” a turning point, like Yesha‘yahu’s, when all of God’s purposes for humankind and the world would be fulfilled, those purposes that have inspired people wanting to call themselves saints since Yesha‘yahu’s day and beyond.

For my ancestors, those would-be saints, as for their biblical role models, there was ultimately no distinction between the sacred and the profane.All of life was encompassed by the injunction to be holy. From how you make your clothes to how you raise your food to how you make your living, absolutely everything was part of the gospel of the kingdom. Mormons would easily have agreed with Josephus: “Moses did not make religion a department of virtue, but the various virtues—I mean, justice, temperance, fortitude, and mutual harmony . . . —departments of religion. Religion governs all our actions and occupations and speech; none of these things did our lawgiver leave unexamined or indeterminate.”The Mormon symbol for this all-encompassing mandate of holiness was the all-seeing eye above the beehive with its busy bees and the inscription “Holiness to the Lord.” Today, we see that inscription, though not that image, only on Mormon temples. But in earlier times, we might also have seen it on a warehouse or a ward house or a storefront; it didn’t matter. All were equally the province of God.

The critical question now is whether this biblical paradigm embraces us. For myself, the answer is an emphatic “Yes!” despite the fact that I haven’t worshipped in a Mormon chapel (or any other) for twenty-five years and despite the fact that I don’t even believe in God—at least not in the sense that my ancestors or my fellow Mormons today do.

What draws me, and I hope others, to the biblical tradition of Zion is that it is a defining, and, in some ways, definitive expression of the human search for goodness. It recommends itself, even imposes itself on us, not because it comes from an omnipotent, gray-bearded, cosmic tyrant, but because it is the summary of our own search for meaning and grounding in life. It is an expression of the human need, if not the divine imperative, to be sanctified. And what is the sanctification that we seek? It is a comprehensive goodness, a life lived in accordance with principles of fairness, compassion, and community with others. It is a life based on the rejection of arrogance and superpower. The great biblical imperative is: “You shall have no other Gods before me.” In my secular interpretation, this is our way of warning ourselves against the idolatry of the self and the worship of our wants and desires.The biblical paradigm of Zion is a way of life that knows contentment. It’s a way of life that is at peace with the world, in both the human and the physical senses of the word.

But it is not the American way today. We have been at war with the physical world—our own world, no less—since the day we set foot on Plymouth Rock. No nation in history has enjoyed such natural bounty or destroyed it so quickly. In just three centuries, we have consumed our way through a continent of resources, a continent of virgin hardwood forest that we simply burned, a continent of prairie that was an American Serengeti, a continent of wildlife where salmon were once so common they were called poor man’s hamburger. We brought the beaver to the edge of extinction. We slaughtered 60 million bison and left their carcasses to rot. We dammed almost every river and stream in America, destroying riparian ecosystems by the tens of thousands. We’ve scraped mountains to the ground. We’ve drained and developed wetlands. We’ve poisoned our air with acid and soot and our water with mercury. It’s not an exaggeration, therefore, or a metaphor, to say that we have waged war against our own world, just as we have waged war against the native human inhabitants of this world, with equally deadly results. And always, it has been a war without limits or compromise. We have insisted that the natural world must surrender to us unconditionally.

Punctuating this perpetual natural war have been spasms of smaller-scale war instigated by us and directed at other people beyond our borders: Mexicans, Spaniards, Cubans, Koreans, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians, Iranians, Grenadians, Panamanians, Iraqis, and Afghanis. We also fought the large-scale and astronomically costly Cold War with the Soviet Union, which sent probably hundreds of thousands of innocent people to their death as “collateral damage” from proxy wars, political subversion and revolution, environmental destruction, economic deprivation, and nuclear fallout. Although the Soviet Union never dropped a bomb on us, we exploded over 900 nuclear weapons on our own soil, 100 of them in the open air.That’s fifty times as many as we dropped on our then-mortal enemy, Japan. We even contemplated the possibility of waging nuclear war at an “acceptable cost” of tens of millions and perhaps hundreds of millions of lives.

In saying that the biblical way embraces me, I am saying that I reject the American tradition of war. And I reject much of what we call the American dream, which has been the American nightmare for uncountable billions of other living things that we have destroyed. Our way today seems to me to embody precisely that worship of the self and of the selfish that is the great sin in biblical thinking, and it seems to be tending toward the same sort of result that biblical arrogance did. If there is a Jungian archetype for cataclysmic, self-induced destruction, we are living it.

The more I think about the problems we face today, therefore, the more I find myself, infidel though I am, gravitating toward the way of life pioneered by my ancestors and their biblical models. Does the biblical tradition of Zion, or the Mormon tradition of Zion, have anything to say to us arrogant Americans today? At the heart of my emphatic “Yes!” is the notion that inspired Yesha‘yahu 2,500 years ago: the idea of a community that embraces the principles of fairness, compassion, and dedication to the common cause against the worship of self and superpower.

To be meaningful, the biblical ideal of righteousness, of goodness in action, must be embodied in community and not just in individuals. As I’ve said, in the Hebrew Bible, the focus is almost entirely on community. What concerns priests and prophets alike is Israel’s righteousness, not that of isolated individuals. God’s promises and punishments therefore apply to the people as a whole. If they will be righteous, He will dwell among them and be their protector. If not, they will perish en masse. There is no promise to or concern with individuals as such.This collective gospel continues in the post-biblical ideology of the Messiah, the royal descendant of David, who will lead God’s people in their ultimate resurgence.The Messiah is not a personal but a national savior. In short, the Hebrew Bible is a teaching less for individuals than for a people. It is a handbook for creating a holy nation.

The early Mormons sensed this collective dimension of the Hebrew gospel intuitively if not explicitly. Unlike most of the rest of religious America and very much unlike other settlers of the American frontier, the Mormons thought from the beginning in collective terms. The heart and soul of early Mormonism was the sense of being called to build a new society, Zion. This objective of building Zion, or as Mormons sometimes called it, the City of Enoch, was what created the first Mormon communities in Kirtland, Ohio, Independence, Missouri, and Nauvoo, Illinois. From the start, Mormons felt compelled to build a new community. They were not content with simply becoming converts to a new religion and living where and more or less how they had lived before, with just a change of ideology. They were not content to be so many independent selves trying to live righteously on their own. Thus, religion, as other Americans tended to practice it, held no interest for the Mormons. They weren’t out simply to live a pious life but to create a new world. This mentality ultimately brought them west when it proved impossible to build their ideal community among other Christians. And, the Zion mentality was, in large measure, responsible for the success of the Mormon Saints in an environment that few thought inhabitable.

Common faith gave the communitarian Mormons what modern Communists lacked, a basis of voluntary but total commitment, of genuine and total passion.Their common faith gave them something that frontier expedience, however great, also could not: It made their experience meaningful. It did this by putting their experience in a context that linked them in a common cause to each other and to generations past and future without end. It made their life a living sacrament.

Sacraments not only connect people to God but people to people. Sacraments are a treasured inheritance passed down from generation to generation. They are entered into with others in common worship. In a Mormon temple marriage, for example, bride and bridegroom kneel facing one another across the altar. Behind each of them is a mirror, and the two mirrors, reflecting one another, create a series of kneeling couples that stretch on in each direction into eternity. At the center of this procession of life is the couple being married now. Eternity ends and begins in this moment. It is in the nature of a sacrament to focus eternity in the present moment. To live sacramentally, therefore, as the early Mormons tried to do, is to act in each moment with the awareness of an eternity leading to and from this moment. It is to act with awareness and appreciation of those who have preceded us and who will follow us in the procession of life.

This sense of the sacramental in the everyday, this exaltation of the everyday, is what the religious worldview, and above all the Zion worldview, offers, even if it is secularized as in my case, that no mere ideology can provide. My emphatic “Yes!” is therefore a cry to bring a kind of Zion to life in our time, a self-sufficient, morally driven, sacramental community that at least on essential points of first principles is, as Mormon scripture puts it, “of one heart and one mind” (Moses 7:18). In such a community, steward ship of the earth would top the list of first principles because, without a sustainable relationship with the earth, life itself is not possible. In such a community, responsibility for insuring that the procession of generations continues would be a first principle, and it would be a sacrament. In such a community, day-to-day decisions—like how we build our homes, how we raise our food, how we get about—are sacramental decisions, because they impinge on eternity. In 1857, Mormon apostle Heber C. Kimball addressed the Saints in Salt Lake City on the sacrament of life:

We dedicate and consecrate the wine or water that we partake of in the sacrament, and we also dedicate the bread to the Lord; and it should be just so with everything; it should all be dedicated to the Lord; and upon all that we do and put our hands unto, we should ask his blessings. We should never meddle with anything on this earth that we cannot lay our hands upon and bless and dedicate and consecrate to the Lord. . . .

Brethren, go out and dedicate your gardens, and when you get a tree that you want to set out, dedicate the ground, the root, and the elements that you are going to place around it, and ask God to fill it with warmth and with power to vegetate. Dedicate the seed that you are going to put into the earth, and then dedicate the earth, and nourish it when it springs forth . . . and do not say that it cannot be quickened, for I say it can. . . .

The Lord will now bless our labor; he will bless the fruits of the earth, he will bless our tanneries, he will bless our sheep, our flocks, and everything we undertake to handle and manage . . . and we will dedicate and consecrate them to God, and we will ask God to fill the earth with the resurrecting power; for life is the resurrecting power . . . and it is that power which brings forth vegetation; it is the same power which brings forth food and raiment; and by the same power we shall be brought forth in the morning of the resurrection.

Is my hope for a Zion community in twenty-first-century Utah any more than the pipe dream of Yesha‘yahu or Jesus or St. Benedict or Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball? Probably not. We don’t seem to be able to stick with this vision long enough or with sufficient dedication to build the new society that these followers of the biblical way had in mind. At the same time, I must also confess that I have even less hope for civilization as it stands, which seems to be on the brink of self-induced catastrophe. If there is any hope for our civilization, it is the hope that inspired the biblical tradition of Zion.

As the boy in the Passover Seder asks, How is this time different from all others? Why should there be any more hope now for the establishment of Zion than in the days of Yesha‘yahu or Jesus or Brigham Young? The answer is that we, in ways that go beyond mere religious belief, really do live in the last days. If these aren’t the last days of history or time, they are the last days of civilization as we know it. There is an apocalypse on our doorstep. It’s called climate change.

Apocalypse is much more than an old-fashioned word for disaster. We do face disaster and on a scale beyond anything we have ever experienced. But we face apocalypse in the truer meaning of the word, which is literally “uncovering.” The apocalypse of climate change is the uncovering of the fact that our present way of life is utterly—root and branch—unsustainable. Climate change is the coming together, the perfect storm, of the many different manifestations of our worship of self and superpower. Climate change is the result of the reckless pursuit of narrowly defined self-interest at others’ expense. It’s the result of the injustice of 6 percent of the world’s population consuming a quarter of the world’s fossil fuels and producing 20 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. It’s the result of the hypocrisy of this 6 per cent wagging an admonitory finger at the Third World about emissions and doing nothing about its own. It’s the result of a healthcare system that spends billions treating heart disease, obesity, and diabetes—the diseases of an indulgent lifestyle—while leaving the lifestyle in place. It’s the result of the worship of consumption, in which no product is too inexpensive and no true cost too invisible. It’s the result of an attitude that views living systems of all kinds, including our own bodies and minds, as mere resources to exploit for profit. Climate change isn’t just another in a series of problems. It’s the sum of all of the many problems that we have faced and failed to solve or refused to solve in our idolatry of the bottom line.

Standing against this tendency of our civilization is the biblical concept of Zion, the good society that embodies our deepest aspirations for individual and social transcendence. While these two aspects of our humanity have always been in conflict, they come to blows now as never before in the problem of climate change. The next few decades will either be the moment when humans at last take something like the path we imagined for ourselves three thousand years ago in ancient Palestine, or they will be our undoing. Climate change will be the catalyst for deep individual and societal transformation, or it will be our Deluge, our Babel, and our Exile. This is the moment when myth becomes history. We will create Zion or we will create the Apocalypse. The choice is ours.

In this endeavor, we will succeed together or fail together. Climate change is the result of systemic problems in our society, and it will be averted only by a systemic response. This fact means that, if all we can muster is random, individual transformation, then we will fail. If, for example, it’s just “environmentalists” putting up solar panels and getting rid of their cars, we will fail. If it’s just the wealthy doing the environmentally responsible thing, we will fail. If it’s everyone acting on his or her own, we will fail. This is something that everyone must do and something that we must do together, with common purpose.

The change we need is as radical as it is universal. One of the paradoxical recent discoveries of climate science is that the piece meal conservation that we have practiced thus far is actually contributing to climate change. When just a few people do all of the right things or a few more people do bits and pieces of the right things, all society as a whole gets is modestly improved efficiency. But a more efficient version of the present system is precisely what we do not want. A more efficient system that is still essentially devoted to utilizing earth’s resources for profit is not progress. We need a complete turnaround, societal repentance, a new collective mind. With 6.5 billion people on earth, soon to be 9–12 billion, we must forever abandon the old way of doing things.

The good news, and really the only good news, is that crisis is the catalyst of change for individuals and for society. In my opinion, it is in our communities of faith that the transformation of individuals and society must begin. It is in communities that have some understanding of and commitment to the biblical paradigm that this transformation can start, if it can start anywhere. I don’t say that this is the only place where the transformation can happen. In any community deeply committed to the underlying principles of Zion lies hope for transformation. But transformation is not what our present American political system is committed to, nor is it what American business is committed to. Both of these are alike and interchangeably committed to profit and self-interest at all costs. Looking at American society, the only place I see communities that could rally around the idea of Zion is our churches.

The degree to which politics and business as usual have betrayed us became abundantly clear in Copenhagen. What happened, or rather didn’t happen, in Copenhagen, even with Barack Obama in the White House and Democrats controlling both houses of Congress, is the truest expression of the degree to which American culture is in thrall to the darkness, the cosmic evil—and I do not speak in metaphor—that is today’s American capitalism. Copenhagen was an apocalypse, a sneak preview of the Apocalypse that will surely come if people of faith do not stand up for the alternative.

By standing up, I don’t simply mean vocal protest, though that in itself would be a step forward, for there is precious little protest in America right now. I mean, first and foremost, individual and collective commitment on the part of people of faith to live the principles of Zion here and now, and to live them radically. And to the age-old principles that Yesha‘yahu would have known, we must now add a new one: carbon neutrality. Until every church and every member of every church is carbon-neutral, we Christians are not living the gospel that we profess.

The imperative for our time, as for Jesus’s, is to repent. The Aramaic word for repentance that Jesus would have used means “to return,” that is, to return to one’s roots, to return to the covenant, to return to God, forsaking competing alternatives. Zion, the covenant community, is the result of such repentance. As long as such a community does not exist, people are, by definition, failing to live up to God’s expectation. In my secular rendition, this means that we are failing to live up to our own sense of what we are capable of. The Greek word that Mark uses for Je sus’s call to repentance is metanoeite, literally, to get a new mind. Jesus invites those who would be his followers to realize that the world has changed and that a new order now governs how they should act. In Jesus’s teaching, the individual new mind and the new kingdom go hand in hand. Followers of this way are in fact the very temple of God (1 Cor. 3:16), the source from which the kingdom takes its strength. The news of Jesus’s kingdom is an invitation for people to believe that a radically different way of life is possible, a way that values people as a manifestation of God and not simply as human resources. Even I, as an unbeliever, can subscribe to this idea. I believe that we can become whatever we imagine we can become.

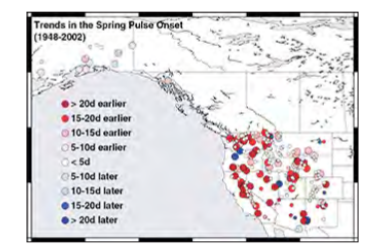

The central problem of climate change has nothing to do with the environment. Ours is not an environmental problem in the way that living in the desert or in the jungle is an environmental problem. Nothing we are experiencing as a result of climate change is dictated by factors outside our control. Not yet anyway. Ours is a problem of impoverished imagination and will. We cannot think outside of the desperately narrow little boxes that we mentally and physically inhabit. And the manifestation of our loss of imagination is neurosis on a scale never before seen in history.Our neurosis—indeed, I would call it psychosis—is so profound that we cannot even see that we are in cri sis, despite the fact that evidence of the crisis is all around us in plain sight. The earlier onset of the spring run-off in the West is one such evidence.

Climate change is for us what the threatened destruction of Israel was for the biblical prophets: a singular opportunity for people to look inward, to reexamine their lives at the deepest level. At least from the prophetic point of view, Israel failed to seize that opportunity. But its failure has been our gain, for it prompted the most extraordinary outpouring of radical ethics the world has ever seen. “Prophecy,” writes Heschel, “is a moment of unshrouding, an opening of the eyes, a lifting of the curtain. Such moments are rare in history.”

It’s easy, especially for those of us who cannot call ourselves true believers, to dismiss the relevance of the prophets. But I can’t. In what Hugh Nibley called the long night of human history, there are precious few shining lights. I think of Mahatma Gandhi, Jesus, and the Buddha of Compassion. And I think of the prophets. What these men represent for me is the refusal to accept that the world we create for ourselves cannot be something dramatically better than what we have seen so far. For me, the significance of these visionaries lies not only in their moral outrage but also in their willingness to think and to do the unthinkable in the quest to transform their people. The prophets asserted, for example, that being God’s chosen people was no protection against folly and self-induced catastrophe. They proclaimed that worship was meaningless—indeed, offensive to God—if it was not accompanied by righteous living. They foretold the destruction of the temple, God’s own dwelling. They pummeled government officials, ecclesiastical leaders, business elites, and ordinary people. And they illustrated their message with outrageous acts guaranteed to shock. There was no idea so sacred, no person or institution so powerful, that the prophets were unwilling to attack it in their goal of shattering the people’s complacency. In the biblical view, to be a prophet is to be an iconoclast. But then, to build Zion, one has to be.

At some point, every society, if it is to thrive, must shatter its icons. These have their proper place. But mistaken for God, they become demonic. Our icons—consumption, growth, profit, extreme individualism, and superpower—now threaten life itself. To overcome these demons, we, like the prophets, must think the unthinkable and we must do it. As in Isaiah’s time, our fate depends on whether we act while there is still time to prevent catastrophe. What holds us back is our own success. As Heschel warns, politics, business, and religion—booming industries and vested interests all—are

. . . isolated, self-subsisting, self-indulgent. . . . The answers offered [are] unrelated to the problems, indifferent to . . . man’s suspended sensitivity in the face of stupendous challenge, indifferent to a situation in which good and evil [have become] irrelevant, in which man [is] increasingly callous to catastrophe and ready to suspend the principle of truth. . . . [T]he terms, motivations, and concerns which dominate our thinking may prove destructive of the roots of human responsibility and treasonable to the ultimate ground of human solidarity. The challenge we are all exposed to, and the dreadful shame that shatters our capacity for inner peace, defy the ways and patterns of our thinking. One is forced to admit that some of the causes and motives of our thinking have led our existence astray, that speculative [or any other] prosperity is not an answer to spiritual bankruptcy. . . .

The prophet was an individual who said No to his society, condemning its habits and assumptions, its complacency. . . .

Prophecy ceased; the prophets endure and can only be ignored at the risk of our own despair. It is for us to decide whether freedom is self-assertion or response to a demand; whether the ultimate situation is conflict or concern.

As a catalyst for change, climate change is a godsend. It will challenge us like nothing else in history. It will be our doom or our finest hour. The choice is ours.

Each evening God takes his shining wares

from the shop window—

mystical chariots, covenant tablets, pearls of great price,

luminous crosses and bells—

and returns them to dark boxes

inside and closes the shutters. “Again,

not one prophet came to buy.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue