Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

Daryl Prays, The Snake River, and Insomnia

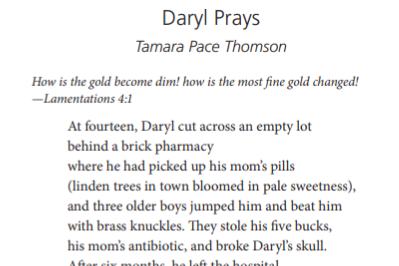

Daryl Prays

How is the gold become dim! how is the most fine gold changed!

Lamentations 4:1

At fourteen, Daryl cut across an empty lot

behind a brick pharmacy

where he had picked up his mom’s pills

(linden trees in town bloomed in pale sweetness),

and three older boys jumped him and beat him

with brass knuckles. They stole his five bucks,

his mom’s antibiotic, and broke Daryl’s skull.

After six months, he left the hospital

with crutches and a baseball cap,

with a crooked knee and erratic hands.

Forty years later, Daryl lives in a group home

where he tells jokes:

Why can’t a bank keep secrets?

Because it is full of tellers!

We laugh—to be polite.

And his hands tremble,

his crutches lean against a mauve wall,

his trucker’s cap is grease coated,

and his pant leg is half tucked into a white

tube sock.

Over the Thanksgiving dinner he offers to pray:

Thank you, God, for the abundance

of divine providence,

and for the farmers who toil to grow our food.

And please anoint us with power, and wisdom,

and healing.

And Daryl says, Many are our pleasures,

dear Lord.

Thank you for the truckers who bring us our food

And for our dear friends who prepare it

That we might be strong and healthy.

Daryl’s lower lip sags like a fractured lamp post—

his eyes are the color of depleted soil.

He says, Bless you, God, our flaming sword,

our light of kings, our feast of comfort,our sanctuary. Bless you.

The Snake River

The night is cool but the window

is open—lilac, lilac, lilac fills the room;

robins begin their call early and I awake.

A week ago, my father’s last sister passed—her ashes

await a grave in Burley where alfalfa

and cottonwoods are greening

this mid-spring beneath sun and rain and moon.

I remember, from my childhood,

a night near the river, its movement orphic,

the undying smell of mud and water—

wading, sinking—my feet

sucked under the splintered dock,

trees and then water above my head,

the taste like mollusks on my tongue.

Just twenty yards from me,

my father and his sister visited

in her home on the water’s edge—

I was their unknown oblation

to the river, to the night,

to the slime of the bank my fingers clawed.

But it couldn’t be that the river filled my lungs,

as I remember,

and the medallion in my pocket,

was it real? Etched with the profile

of a Native chief in feathered

headdress, stern chin, eye of a stallion?

I remember this:

all was silent but for the kickof my feet against the dock.

Insomnia

Sleep aids fail her—from chamomile to Ambien. Nerves alight like

electrons moving in a wire. Power lines cross the yawning canyon and

pullulate and seethe with wind—the sound gushes past her ears and

all but drowns the who’ll who’ll who of a perched owl. What memory

comes to her is the layered tissue open through muscle to the bone

of her sister’s knee when they chased a wheat-colored hare westward

across a field where old barbed wire slept decades after the last farmer

had abandoned the mountain’s short growing season. And, later, how

the calico dress her sister wore teased the fibrous scar that was shaped

like a sickle cupping her sister’s knee. Leaves in decay beneath scrub

oak smell of stale tobacco spilled in her leather bag. Aster petals curl

in muteness. She longs to prophesy. To see into the future and not only

the past—for her sleeplessness to presage visions. To see fire on the hill.

In Aeschylus’s telling, she remembers, Clytemnestra learned the news

of fallen Troy, during her midnight watch, from flames of signal fires:

fire for word of fire. Troy was burning. Clytemnestra was no woman of

visions or senseless dreams—yet she prophesied that Agamemnon and

his men were eating breakfast on the last remains of Troy. But here, in

the clamor of canyon wind and the withering year, there is no burning,

no idiot’s tale to tell, no fire for word of fire, only the call of an owl, the

perishing of green things, the sightless and sleepless night. And, she

thinks, What light can match my darkness?

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue