Articles/Essays – Volume 46, No. 2

Communicating Jesus: The Encoding and Decoding Practices of Re-Presenting Jesus for LDS (Mormon) Audiences at a BYU Art Museum

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

There is a growing recognition among scholars that museums are discursively constructed sites. One scholar noted that museums often are merely a “structured sample of reality” where science empowers their message. Alternatively, museums might encourage a pseudo-religious experience of ritually “attending” them— factors, some critics observe, that reduce the probability of resistant readings by patrons. Either view suggests a potential for tension between the secular and the religious, or perhaps the discourse of the museum versus the worldviews of patrons. This paper addresses this tension by examining the meaning-making practices of a museum and patrons at an art exhibit featuring both original religious paintings and digital media at a Carl Bloch exhibit at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art (MoA).

Historically, traditional museums emphasized the sanctity of the artifactand the ritualistic practice of “attending” them. However, since the advent of cinema and other competing media, museums have retooled their relationships by increasingly emphasizing new media rather than artifacts to appeal to a larger number of people. Curators are adding interactive features and investing in public relations campaigns while retooling their exhibits to appeal to populist views. These shifts in museum presentation strategies alter the ritual-symbolism of attending a museum and of fetishizing the object—creating the potential for tension between educating and entertaining the patrons.

When history is conflated with theology and technology (as might be the case in an exhibit featuring historical works of religious art), which perspective is dominant in the discourse of that exhibit? Which elements resonate with visitors? Does the exhibit emphasize the historic or the religious, and how is its message either resisted or reinforced by the religious views of the patrons? This paper addresses these questions with an analysis of an art exhibit at BYU featuring Carl Bloch paintings of New Testament stories.

Background

Carl Bloch: The Master’s Hand was the title of the religious art exhibit presented at the MoA from November 12, 2010 through May 7, 2011. The exhibit featured five large altar paintings (one owned by the museum and others borrowed from churches in Sweden and Denmark) and other works of the nineteenth-century artist (including portraits, landscapes, and sketches). Entrance to the exhibit was free, but patrons paid a fee to use an iPad with interactive features that included panoramic views of original placement of altarpieces and churches where they originated, discussions of the art by MoA staff and LDS Institute instructors, and recordings of Mormon leaders’ sermons about Christ.

The exhibit was preceded by a public relations campaign that included articles in BYU and MoA magazines, press releases across the media (especially in Church-owned newspapers, magazines, radio, and television stations), an official website from the MoA, and a BYU television documentary about Bloch and the exhibit. Although the media blitz extended beyond Utah borders, the emphasis in church-owned media certainly made clear the primary targets were people within the LDS community.

This study draws in part from Stuart Hall’s encoder/decoder model, which was initially used to show how audience members’ socioeconomic standing could narrow their interpretation of mediated texts. We expand this model in two ways: first, we read a museum (rather than television or newspapers) as a text; second, we move beyond the politics of class—focusing instead on religion in both the production and interpretation of meaning. Given that patrons describe museum attendance as a numinous experience, we seek to know whether such experiences are plausible given various institutional pressures and technological filters accompanying the exhibit.

Our approach recognizes that museums are organized using the sense-making practices of both producers and audiences, and that attendees bring to an exhibit varying social practices and worldviews which influence their experience. The interplay of religious culture and museum discourse plays a significant role in the process—at least in the case of the Carl Bloch exhibit. Hence, patrons are likely to apply a “negotiated” reading of the exhibit. Such a reading “accord[s] the privileged position to the dominant definitions of events while reserving the right to make a more negotiated application to local conditions.” We suggest that religious discourse can be localized in the interpretive practices of museum attendees particularly because “other discourses [especially religious ones] . . . are always at play besides those of the particular text in focus.” These other discourses, Hall later notes, mean that we see our subjectivity as disunited—a site of struggle—rather than as ideologically cohesive.

Moreover, the Bloch exhibit is of special interest because it integrates discourses of history and religion in an exhibit marketed primarily to appeal to Latter-day Saints in Utah. This interplay of history, art, and religious discourse gives rise to a number of potential encoding/decoding strategies because in some instances museums are empowered precisely because they are perceived in the public consciousness as a powerful means of understanding, organizing, and managing the world using an “object-based epistemology.” Furthermore, the accompaniment of the interactive iPad feature adds yet another facet to the rubric of potential influencers in this particular exhibit.

In this study we examine the role of religion in this rubric of meaning-making for museum patrons. This approach moves be yond a cultural studies approach that fetishizes the text by instead “locating both texts and audiences within broader contexts that articulate the identity and effects of [the] practice” of attending a museum.

Museums as Media

The literature is replete with examples of how museums in fluence or reflect culture. Pearce suggests that museums are communicative venues in which diverse media coalesce to generate synergist effects. Museums also offer a representational narrative of other realities and at times create a sense of the numinous by fetishizing the objects they present.

Museums are in many ways akin to churches or other religious monuments in the way they exhibit culture and artifacts. They are like religious shrines or temples in their role as repositories of knowledge; they also display objects that mimic the sacred in that they are beyond the gaze of patrons. Attending a museum exhibit has also been likened to participating in religious ritual practices. The discourse is enhanced by layouts that invoke organized walking or designs that discourage interaction among visitors, often requiring of their patrons “respect for the collection” through their “do not touch” discourse. In this sense, museum attendance is identified as a ritualistic participatory experience akin to religious worship.

Only a handful of studies have examined museums in an effort to determine how meaning is contested when both encoding and decoding practices are considered. These studies focus primarily on the hegemonic nature of museums and the limited capacity of consumers to resist the “preferred” text. Bella Dicks’ analysis of a heritage museum in the United Kingdom suggests that the producers of the exhibit intentionally offered a “preferred” message that was ambiguous (and relatively open) in order to appeal to a collective memory of consumers. Analysis of consumer readings of this site reflected that openness. However, visitors of the Newseum in Arlington, Virginia—the first “interac tive museum of news”—negotiated through a relatively closed text. By drawing on the collective memory of major news events, and by equating the economic incentives of newspaper owners with freedom of the press, this exhibit effectively limited the capacity of attendees to resist the dominantly pro-newspaper industry message.

How patrons define and practice religion is also key to understanding the communicative strategies of museums. Patrons are increasingly willing to have religious-like experiences within museum walls. We have previously demonstrated that the scientific elements of a Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit in North Carolina were co-opted by the religious discourse prevalent in the exhibit’s public relations strategy and the religiosity of its guests. Visitors typically expressed religious sentiment accompanying their visit to the museum—especially when they saw actual scroll fragments.

In this case, the objects themselves were fetishized as a means of bringing museum guests closer to the location of Jesus and biblical writers. For these guests, the experience of the numinous was enhanced primarily by their proximity to original scroll fragments rather than the presence of the exhibit’s interactive features.

This finding adds insight to the question of the empowering capacity of interactive and digital media features in traditional museum settings. However, Murray argues that allowing visitors merely to “push buttons” to move through a narrative is not especially empowering. Furthermore, high-tech interactive features might not always add to the educational value of an exhibit. One study of an interactive Holocaust museum found that visitors were reluctant to engage with interactive features that offered information beyond what they “already knew.”

Religious Art and Worship

Of course, in an exhibit featuring religious art, the power of attendance as religious ritual increases. This is because art possesses the essential elements of religion (i.e., deep feeling, belief, ritual use, and the ability to create community). Morgan and Promey trace a growing trend in the study of religion recognizing the contribution of cultural artifacts (art and objects) as elements of religious practice. Quite a few scholars in recent years have suggested a need to better understand the interaction of religious identity and popular culture.

Geertz maintains that a religion’s appeal “rests in turn upon the institutions which render these images and metaphors available to those who thus employ them.” Religious art has been used since the earliest days of Christian worship, and in an era of mass-produced religious iconography, religious art can be reproduced to expand its sentimental impact, while at the same time enhancing the mystical quality of the original. As Korne gay argues:

Whether it be a statue of the Virgin Mary, a decorative passage of calligraphy from the Qur’an, or mass-produced plastic figurines of Hindu Gods, visual expression is a central element in virtually every religious belief system.

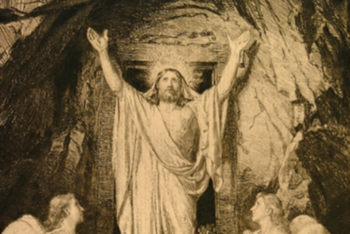

Religious representations are more persuasive when they appropriate cultural referents—culminating in a cyclical reproduction of religious images that are relevant to believers because they have “seen” similar representations elsewhere. Hence, Morgan’s conclusion that believers identified with Sallman’s Head of Christ painting because it assimilated a “long-standing paradigm of his physical appearance as a light-skinned Euro-American man.” Subsequently, other renditions of Jesus continue the cycle—departing little from Sallman’s rendition, resulting in a culturally-bound Jesus who is “more archetypal, more transcendent, [and] less historical.”

The LDS Church has contributed to re-presentations of an archetypal Jesus to be revered by congregants. Sallman’s rendition of Christ was displayed in many LDS churches from the 1950s un til, in the 1970s, the LDS hierarchy began regulating the art that might be hung in chapels. Subsequently, in 1983, church leaders commissioned Utah artist Del Parson to paint a head of Christ. According to Parson, he was instructed to make his rendition more “masculine” than the Sallman image—and even his approved rendition was revised five times until it met the measure of masculinity required by LDS leaders. Despite its emphasis on the “more masculine” Jesus, Parson’s “approved” Euro-American Jesus reflects the archetype. More recently, however, the LDS leadership has been including Bloch’s images of Christ in church buildings and publications. This ability to determine which Christ images are “acceptable” in LDS buildings serves to reinforce archetypal perception of Christ while at the same time imbuing those images with the stamp of the Church’s approval. This, in turn, might add to their appeal as accurate representations of Christ among LDS congregants.

Research Questions and Procedures

Given the potential for contradictory discourses (art, history, science, religion) in an exhibit featuring historical paintings of a European Lutheran artist to be presented at a predominantly Mormon community, we first seek to determine the dominant narrative of the exhibit and its attending public relations campaign. Next, we seek to determine which subjectivity of the visitors is at play when attending the exhibit, as we address the following questions:

1. What is the dominant theme of the exhibit and the attending media campaign?

a. How is it expressed in both latent and manifest discourse?

b. How does it reflect cultural, religious, or historical subjectivities?

2. Is the dominant theme accepted or rejected by attendees (as noted in their blog entries)?

3. Does the public relations campaign promote numinous aspects of the paintings? Do patrons describe numinous experiences as they visit the exhibit?

In this paper, we address these questions with a close reading of the Bloch exhibit patterned after Stuart Hall’s introduction in Paper Voices. This approach requires that we read the museum as a “visual construct, employing symbolic means, shaped by rules, conventions, and traditions intrinsic to the use of language in the widest sense.” We begin with a brief analysis of the public relations efforts preceding the exhibit in an effort to determine the larger narrative accompanying the exhibit. Next, we examine the exhibit itself before grounding that analysis in a reading of guest comments dated from the opening of the exhibit on November 20, 2010 until January 10, 2011. These comments were read and sorted in systematic fashion to identify categories of dominant themes.

Given the polysemic nature of mediated events, it is not our intent to suggest that our reading represents the only plausible interpretation. Certainly, attendees bring with them many subjective positions (e.g., self, gender, age group, family, class, nation, ethnicity, etc.). We also recognize that this study is premised on observations in a fixed time and place, so it cannot make a full assessment of the fluidity of cultural boundaries. Finally, we admit that the encoding process is impacted by many factors (e.g., budgets, time constraints, curators’ interests and expertise, availability of specific documents and experts, corporate culture). Hence, as is the case with other mediated texts, we do not claim that the preferred text necessarily reflects the intent of the exhibit’s curators or staff.

Findings

The dominant theme of the public relations campaign and the exhibit itself centers on the religious, rather than the artistic or historical, value of the paintings. The public relations campaign and interactive iPad features work together to embed Bloch’s art within cultural and religious referents of the LDS Church. Moreover, the exhibit itself crafts a sense of the numinous by recreating the experience of visiting a church (through both the layout and design of the exhibit and interactive features of the iPad) and injecting theology into discussion of the paintings. Bloch’s artistic ability, when it is expressed, is also embedded in religious discourse. Furthermore, both the museum and public relations messages frequently distinguish Bloch’s art from that of other artists—creating a latent theme that suggests his work is more inspired than other depictions of Jesus. The guest diary entries affirm this narrative with comments typically highlighting religious sentiment accompanying the museum visit.

Public Relations and the LDS Experience

The public relations campaign offers a narrative that highlights the religious power of the paintings and the spiritual message of the LDS Church. Prior to the launch of the campaign, numerous articles and reprints of Bloch’s work had been distributed in official LDS publications (New Era, Ensign, Liahona) that are typically aimed at indoctrinating and enhancing the faith of Church members. The media campaign takes advantage of these same sources, and additional articles and reprints of Bloch’s art are featured in articles and on the cover of Ensign just prior to the exhibit’s opening. Furthermore, the media blitz targets LDS-owned publications in Utah (KSL television, the Deseret News, Church News, BYU Magazine, and Mormon Times). Given the context of these news media, emphasis on the coming exhibit in these publications adds to the religious draw of the work. The message among these church-owned publications emphasizes the power of Bloch’s work to inspire people and also that God inspired Bloch’s art. Bloch is quoted to have said, “God helps me, that’s what I think, and then I’m calm,” in the initial MoA press release—a statement that is reiterated frequently in advertising, newspaper stories, magazine articles, newscasts, a BYU documentary program aired on the local PBS station, and even in the Church’s ecclesiastical monthly periodical, Ensign.

Additionally, the media campaign frequently celebrates the numinous value of Bloch’s paintings as particularly important to Mormons. News releases note that Bloch’s work was not appreciated in much of the art world after the rise of modernism, while at the same time noting that it has been venerated by Latter-day Saints since the middle of the twentieth century after his works were introduced into LDS publications. This observation serves not only as a critique of modernism, but also as a defense of kitschy LDS and other overly sentimental religious art popular in LDS culture. The Church News asserts that Bloch’s work is “beloved by Latter-day Saints worldwide” before quoting museum curator Dawn Pheysey saying of Bloch’s work, “they are powerful, powerful paintings. Bloch’s depictions of a masculine, compassionate Christ is very appealing to members of the Church.” This construct of Christ being uniquely masculine in Bloch’s images bifurcates his “inspired” art from those “effeminate” representations of Jesus found in much of the Renaissance era, while at the same time affirming the LDS Church’s visual construct of masculinity. This construct, while not uniquely Mormon, has special significance given the hyper-masculinity of Book of Mormon men portrayed at Temple Square in Salt Lake City and the Church’s “Proclamation on the Family,” an official statement from the First Presidency of the Church that emphasizes traditional gender roles and reinforces the construct of masculinity as central to LDS theology.

Additionally, we learned that public references to Bloch’s talent serve primarily as a means of celebrating the spiritual nature of his paintings. Meridian Magazine cites curator Pheysey as saying, “ . . . it was [Bloch’s] tender and sensitive soul that defined his ability to portray the plights of others with kind consideration, and his deep-seated faith that enabled him to render compelling images of the Savior with devotion and love.” Pheysey is also cited in the Salt Lake Tribune (the competitor of the LDS-owned Deseret News), a newspaper more popular in Salt Lake City among non-Mormon residents, noting that Bloch “presented a Christ that is divine but approachable.” This “approachable” interpretation of the Bloch painting contrasts with that of MoA director Campbell Gray, who is quoted in a BYU magazine: “[Bloch] employs visual devices to engage the viewer in a direct moral conversation about the personal choices proposed by a painting’s story.” Gray then concludes that the exhibit will “ . . . affirm Christ’s mission of salvation and, at the same time, challenge the viewer to make tough choices that bespeak living faith.” Despite the heaviness of this latter statement when contrasted with Pheysey’s more approachable account, both agree on the spiritual nature and force of Bloch’s work—a message repeated throughout the public relations campaign. Even the Standard-Examiner, an independently-owned newspaper in Ogden, Utah (a predominantly LDS town) draws from this perspective, adding after commentary on the brush-strokes of the artist that “what draws viewers to Bloch’s paintings . . . is the artist’s sensitivity and compassion.”

These and similar statements throughout the public relations campaign coalesce with an approving nod of LDS leaders in Church publications to generate an expectation among the faithful Latter-day Saints of experiencing the numinous when visiting the museum. The taken-for-granted message throughout the campaign advances a latent discourse that distinguishes Bloch from less-approved artists, elevates his work, and occasionally suggests a particular “Mormon” orthodoxy regarding which forms of religious art or representations of Jesus are inspirational or “correct.”

The Exhibit: Centering on Christ and the Sacred

The exhibit highlights the numinous in three ways: 1) by con structing Bloch as uniquely special to Latter-day Saints, 2) by recreating the experience of attending a church (in both physical and virtual space), and 3) by offering interactive features that integrate LDS doctrinal or spiritual messages (rather than emphasizing the historic or artistic) when describing Bloch’s work.

The exhibit itself is consistent with the media narrative—often emphasizing the “unique” appreciation among Latter-day Saints of Bloch’s work. Additionally, the layout and design join interactive features that highlight the sentimental and religious experience. The dominant text also presents Bloch’s religious art as consistent with Latter-day Saint views of Jesus. The latent theme not only attributes Mormon views of Christ to Bloch’s art, but it also conflates his unique representations of Jesus (much is said in the exhibit to differentiate his work from that of other artists) as peripheral in the world of religious art in much the same way that the LDS Church is viewed by many non-Mormons as an outlier (at best) among Christian churches. As such, Mormons are presented as more highly sensitive to (and perhaps appreciative of) Bloch’s work than other Christians or art critics. In this way, Bloch’s life and work resonate with the Mormon experience of practicing faith outside the mainstream culture. Furthermore, the interactive features and layout of the exhibit integrate LDS sermons and commentary that further embed the discourse within the Latter-day Saint experience.

Upon entering, guests are introduced to Bloch’s native county in a room that is offset from the remainder of the exhibit. Here, a panoramic display of Denmark, Sweden, and several cathedrals is projected onto the walls surrounding seated guests as classical music plays. The narrator informs visitors that Bloch’s art is unappreciated in much of the world (since modernism), despite being revered by Latter-day Saints. This narrative, combined with music and scenery, evokes feelings of awe as majestic scenes from a bygone era in Europe surround guests.

The remainder of the exhibit is structured to recreate the experience of visiting the cathedrals where the paintings usually hang. The five altarpieces hang in recessed archways much as they did in their original churches. The strategic use of museum lighting and recessed archways enhance Bloch’s use of light and shadow, making these particular pieces appear three-dimensional—a quality that enhances a sense of “being there” in the presence of Christ.

The interactive features of the iPad enhance this experience by recreating panoramic views of the cathedrals from where the paintings were borrowed. These features allow guests to virtually visit the paintings in their original setting, while viewing the cathedral space, altars, stained glass windows, domed ceilings, and even the church grounds in Europe. This creates an immersive atmosphere that equates visiting the MoA in Provo, Utah, with touring the sacred spaces in Europe where these paintings are used in conjunction with worship services.

The placards accompanying the paintings also reinforce the religious message of the art, with emphasis on the New Testament and additional information about the history of the particular piece at hand.

Similarly, the iPad narrative emphasizes the sacred over the historical or artistic nature of the exhibit. There are three primary interactive features on the iPad which accompany each of the five altar pieces: the first offers commentaries about the message/painting itself (with audio, print, and/or video segments), the second link offers explanations of the artistic nuances of the paintings (allowing visitors to choose a particular element of a painting to activate another narration), and the third recreates panoramic views of the paintings hanging in the churches (many in the sanctuary) from which they came.

In our interaction with the first two features, we discovered that the religious message of the paintings was almost always central—even when the touch screen icon promised to link patrons to a detailed analysis of the Bloch’s artistic approach. For example, the information for Christ and the Young Child offered three interactive links titled, “Who is this child?” “Why does Christ command us to become as a child?” and “How should we behold our little ones?” These links feature a video of Hanne Korsbey (parish council president, Sankt Nikolai Kirk, Holbaek, Denmark, from where the painting was loaned) noting that all of us are children of God; another video featuring Jared Ludlow, a BYU professor of ancient scripture, sharing his witness of the need to become like a child to enter heaven; and finally, an audio clip of an LDS general conference talk by Jeffrey R. Holland (one of the twelve apostles of the LDS Church) referring to children entering the kingdom of heaven (accompanied by a reference to Luke 18). Similarly, the interactive feature for Christ in Gethsemane offers three links that also emphasize the religious (“Biblical Context,” “The Divinity and Humanity of Christ,” and “Understanding Christ’s Sufferings”) rather than the artistic merit of the painting. The accompanying interactive narrative features LDS scriptural references about the suffering of Christ, quotes from the New Testament, a video of a BYU professor sharing his witness of Christ’s atonement while contrasting the LDS belief about the atonement with what may be portrayed in Bloch’s image, and also an audio track of another LDS Church apostle (Neal A. Maxwell) giving a sermon on the power of redemption through Jesus Christ. These interactive features—despite drawing from a variety of sources (scriptures, scholars, non-Mormon clergy, and LDS leaders)—all deliver a similar message emphasizing the divinity of Christ.

We learned that even interactive features promising to explain the artistic attributes of the paintings typically addressed the dominant religious narrative instead. For example, in an iPad link promising to offer insight into the artistic methods of Bloch, we found six references to Christ in Gethsemane, all of which emphasized the religious. These included an audio narrative explaining that the painting serves as “a vital reminder of the atonement,” Pheysey explaining the LDS belief that the atonement happened both on the cross and in the Garden of Gethsemane, Ludlow contrasting Bloch’s winged angel with non-winged angels in LDS art (and also testifying of the eternal nature of Christ’s suffering), two references to Hebrews 12:12, and a cursive script that reads, “wherefore lift up the hands which hang down.” The only reference specifying Bloch’s artistic ability on this page was titled “Dark Background,” where the narrative explained that Bloch used shadows in this painting to emphasize the heaviness of the moment for Christ in Gethsemane. However, this solitary reference to the artist’s method is still embedded with a religious message, this time from LDS Church President Thomas S. Monson, in a video capture saying, “No mere mortal can conceive the full import of what Christ did for us in Gethsemane.”

Diary Entries: A Sense of the Numinous

We examined 1,000 comments in the diaries. These diary entries generally mirror the dominant religious theme presented in the public discourse about the exhibit. The majority of comments emphasize either the sacred experience of participating, or the beauty of the art (which typically overlaps with a sense of the numinous). Secondary were references to Bloch’s artistic ability.

References to deity (God, Christ, etc.) were dominant (955 references), but this was expected given that Christ was the subject of each painting in the exhibit. Beyond that, we discovered five major themes in the comments, some of which overlapped: those highlighting the numinous (423) and the beauty of the art (266)— accounting for 70 percent of the major themes—followed by comments about the artistic ability/talent of Bloch (213), the exhibit as a testimonial or referent specifically to doctrinal statements unique to the LDS Church (65), and a small number of references to scripture (7). Only 21 references were made about the iPad; most were positive, focusing on how it gave them more information. Only one guest expressed disappointment that the interactive features highlighted the “sugar-coated” kitsch of Mormon culture, rather than a more in-depth analysis of the corresponding works of art.

In terms of the numinous, patrons most often expressed feeling God’s spirit attending their visit, followed by comments indicating they were inspired, uplifted, moved to tears, and that their faith was strengthened as a result of the experience (Figure 2).

For these patrons, attending the exhibit was akin to walking in sacred space. Patrons’ comments make evident the numinous nature of their visits:

There is a reverence and power in Bloch’s work that truly touched me. The spirit of this exhibition is exquisitely moving. I can honestly say I feel closer to my Savior as I learn more of His life and message through these depictions.

I was overcome with emotion as I walked through the exhibit and looked at the art and thought of my Savior Jesus Christ. It was truly moving and beautiful!

As I viewed one of the large paintings, I closed my eyes and said a prayer, receiving some direction in my life. The spirit is present in these halls.

My first view of the exhibit was a spiritual moment I will long remember. It brought tears to my eyes and love to my heart for this dear mans [sic] work and talent.

Our second key finding was that the conversations about the artistic abilities of Bloch were framed within the context of the religious. The emotional/spiritual relevance of the experience was prevalent in comments about the beauty of the art and the abilities of Bloch as an artist. Typical were comments framing Bloch’s talent and ability as evidence that God inspired him:

The art of Bloch was amazing to me. His brushwork, his scope, his unfailing concentration on every detail, his ability to portray the range of human emo tion, his use of color and light, and so much more all broadened and enriched the spiritual dimension. Truly, he knew the Savior.

Surely his talent which he worked on for very many years was God-given.

These remarks are not only illustrative of the link between talent and religion for these guests, but are also reflective of the taken-for-granted appeal of archetypal renditions of Christ re-presented by the LDS Church in meetinghouses, temples, tourist destinations, and church literature or media venues.

Numinous sentiment was enhanced by the experience of standing before the originals (or “actual” paintings, to use the term of many patrons), rather than because of the virtual experience offered by the iPad. This sentiment is summarized by an anonymous entry stating, “I really like these paintings because they are so often seen at church buildings, but being able to come here and actually see them in real life is a completely different experience,” or, as noted by another observer, “Christ’s power is evi dent in these paintings.” To some guests, this inspiration was indicative of Bloch’s link to the faithful Latter-day Saints, even though he was not himself a Mormon:

I was really amazed by how when [sic] Carl Bloch wasn’t even LDS, he made a gigantic difference in the church with his talents in art.

Bloch depicts the facial expressions very well, explaining the feelings of the people and the mood of the painting. . . . Even though he was Lutheran, I feel he was inspired by God to paint and etch these for us so we can draw closer to Christ.

These comments are among the many that coalesce to demonstrate how the experience of the visitors is one that integrates spirituality and the talent of the artist within the framework of LDS theology and culture. Taken for granted is the archetypal Je sus portrayed by Bloch in his work—one that the patrons identify with because they have already familiarized themselves with Bloch images hanging in LDS churches or reprinted in LDS publications. In this context, Bloch himself is appropriated by the Church, the museum, and its guests as “one of their own.”

Discussion

In this study, we see the power of merging cultural referents of Jesus with the authority of the LDS Church in a museum setting that itself recreates a sense of religious ritual. Despite the possibility of a number of subjective readings of the exhibit, the vast majority of visitors accepted the preferred reading of the exhibit that appropriated the images of Christ and works of Bloch as sacred. By framing the exhibit as more religious than artistic, LDS patrons are given an instructive frame within which to experience and discuss the exhibit. From the data collected here, we learn more about the strategic nature of campaigns in accomplishing these goals. In this case, positioning the display within the context of Mormon theology is a key finding; endorsement from Church leaders was implicit from the outset. Given that hierarchy is fundamental in Mormon theology, the promotional frame is seen as trustworthy. Something is also learned about tactics in this regard. Placing the exhibit in an LDS framework was done through authoritative media (i.e., trusted sources within the religious culture). A communication strategy of the museum itself (and LDS sources) created a religious frame from which to subsequently view the originals when later attending the museum. Analysis of the campaign reveals meticulous strategizing about the main things visitors should glean before their actual visit. Although we cannot draw conclusions as to whether the public relations strategy and museum display emphasized the sacred because it was endorsed by LDS leaders, or because such an approach would likely draw a larger crowd to the exhibit, we do come to realize how intricately planned and sophisticated Church museum display can be.

Much is also learned about the effectiveness of the campaign, although there is always some space for independent thinking. Patrons’ experiences were more numinous than critical/analytical; the great majority were deeply affected at the level of deep feeling in a way that unified them with LDS beliefs. Not only is the museum a source of the numinous, but it can also reinforce commitments within the context of a specific denomination. It is possible that after seeing the promotions, adherents attended hoping to strengthen devotion to the Church in a pre-planned way.

Although less the case, artistic critique also occurred despite the fact that it was deemphasized in the campaign. That is, many patrons also discussed the quality and nature of the artwork. This underscores the aesthetic power of art to elicit aesthetic commentary, although this was not the dominant experience. Critical discussion may be difficult given the public framing and packaging of the exhibit as upholding Mormon doctrine and theology. It is justifiable to conclude that museums can be a source of significant religious experience, but the nature of that experience can be affected through promotional efforts. These findings suggest that the museum is and will continue to be an important subject for researchers of media and religion.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue