Articles/Essays – Volume 44, No. 3

Alma’s Experiment in Faith: A Broader Context

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

The thesis of this paper is a modest one, namely, that reading the Book of Mormon with an eye to its literary context significantly enhances the reading experience regardless of whether one’s objective is instruction, insight, aesthetics, or merely the pleasure of discovering coherence in its various details.A necessary corollary is that the Book of Mormon, as a text, is sufficiently crafted to warrant such attentive effort. There is nothing remarkable about the suggestion that internal context matters—that even a minimal level of understanding of any scriptural passage requires consideration not only of who is speaking, why, and to whom, but also of how a particular verse fits into a larger argument or interacts with nearby passages, or of how a discourse re lates to either its immediate or extended corresponding narrative. But this is not the manner in which Latter-day Saints typically read the Book of Mormon, either individually or as a community; even as we make our way sequentially through the book, we are much more likely to reflect upon isolated doctrinal proof texts or paraphrased narrative episodes.

I will attempt to demonstrate a more integrative, contextual approach for reading the Book of Mormon by focusing on a single passage, Alma’s proposal for an experiment in faith found in Alma 32, although any number of other Book of Mormon segments could be equally employed by way of example. One advantage of considering Alma’s experiment in faith is its wide familiarity, since any deepened understanding can thus be more readily attributable to a heightened attention to context. Another advantage in considering this segment on faith is that the verses in question comprise just a portion of a larger discourse which itself is closely tied to an adjoining narrative. This situation is not atypical for other doctrinal passages; most are embedded in sermons, and most Book of Mormon sermons do, in fact, have clearly identified narrative contexts. Alma’s comments here are part of a discourse delivered to impoverished Zoramites in Antionum as part of a missionary campaign with specific political and religious objectives (Alma 31:1–5). Such nesting of a scriptural passage within a doctrinal argument within a background narrative renders a contextual analysis not only fitting but perhaps even indispensable for responsible reading.

A final advantage in considering a passage from Alma as a test case for contextual study is that Alma himself is consistently depicted both as one of the Nephites’ most gifted orators and also as one of their most self-reflective and spiritually mature leaders. Not only are Alma’s sermons tightly and thoughtfully composed, rewarding careful attention to his arguments, but he is also presented as a dynamic character whose skills and understanding are repeatedly enhanced by his pondering of personal experiences. Mormon’s minimal editing of Alma’s words enables us to discern his development as it occurs.

Mormon’s editing also assists us in identifying broader and perhaps less-than-obvious contexts for discovering the richer meanings of particular passages. His methods for doing so include juxtaposition, thematic linking, editorial interruption, distinctive phrasal repetition, and the demarcation of literary units. We will recognize several of these strategies in play as we proceed, but I begin the contextual analysis with a consideration of the last of these: the demarcation of literary units.

In the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, the text we now know as Alma 32 was the central part of a larger unit identified as Alma XVI, a chapter comprising contemporary Alma 30–35. Royal Skousen has argued that the earlier, longer chapters (designated by roman rather than arabic numerals) were indicated by marks or blank spaces on the gold plates themselves, which means that they were part of Mormon’s ancient editing.Taking this original chapter division as an interpretive clue, I will presume that Alma XVI in some way represents a conceptual whole. As we seek to discover the coherence manifest in it, I will consider what additional sense this particular context might bring to the passage at hand.

The narrative in Alma XVI recounts the final public events of Alma’s career, namely his confrontation with Korihor and his missionary efforts among the Zoramites. Although these incidents have typically been read as isolated episodes, the original chapter designation invites us to consider their connections. Such an attempt is supported superficially by the episodes’ geographical convergence: Korihor leaves Zarahemla to preach in Jershon and ends up in Antionum, while Alma and his companions leave Zarahemla to preach in Antionum and end up in Jershon. A connection between the episodes is likewise supported by distinctive phrasal repetitions linking the final verses of chapter 30 with the opening verse of 31: both Korihor and Zoram have led away the hearts of the people (Alma 30:55, 31:1) and “perverted the ways of the Lord” (30:60, 31:1). The detail about bowing down to “dumb” idols (31:1) may similarly have been included as a link to Korihor’s curse (30:49–50), since no further use is made of it.

More substantially, Mormon links the two episodes by narrative and thematic commonalities. In both cases, Alma is responding to religious dissenters who have rejected Nephite prophecies concerning the coming of Christ, although their reasons for doing so are different. Korihor’s rejection is based on a rational argument against prophecy itself—“no man can know of anything which is to come” (Alma 30:14, 26)—supplemented by a disavowal of Adam’s fall and hence of the need for an atonement (30:16–17, 25). The Zoramites, in contrast, have not denied the need for redemption (cf. 31:17), but have rejected the coming of Christ nonetheless, primarily—it appears—because of their desire to distinguish themselves theologically from the Nephites by casting the latter’s traditions as “childish” and “foolish” if not heretical (31:16, 18).

The Zoramites’ second doctrinal argument is only implied— namely, that believing in the Son of God constitutes a violation of the strict monotheism presented in the law of Moses. The Rameumpton prayer provides a hint of this rationale when it indicates that “a belief of Christ . . . doth lead [the Nephites’] hearts to wander far from thee, our God” (31:17), as does the Zoramites’ later question to Alma about “whether they should believe in one God” (33:1; emphasis mine). Alma’s appeal to Moses as one who testified of the Son of God, even though this reference is much more oblique than his citations from Zenos and Zenock, further suggests that the Zoramites had denied this very point, especially when combined with Amulek’s emphasis that “the whole meaning” of the law of Moses is found in “that great and last sacrifice of the Son of God” (34:14). Likewise, the narrative detail provided by Mormon—that the Zoramites “would not observe to keep the commandments of God, and his statutes, according to the law of Moses” (Alma 31:9)—may have been included to reinforce the unstated point that Zoramite objections to a belief in Christ’s coming were not based on genuine Mosaic piety. In both situations, Alma is responding to those who do not merely lack belief but who have hardened their hearts against it (cf. 30:29, 46; 33:20– 21).

The Korihor Incident as Narrative Background

Alma’s initial response to Korihor’s challenge to the coming of Christ is less satisfactory than it appears, although this assessment has been deftly obscured by Mormon’s editing. Alma’s task is to demonstrate the legitimacy of faith as a foil to Korihor’s assertion that “ye do not know that there shall be a Christ” (Alma 30:26), but instead he is sidetracked by a far lesser point, but one which will find its own echo in the Zoramite episode. Mormon minimizes our recognition of Alma’s distraction by dividing Korihor’s message into three teaching occasions: to those in Zarahemla (30:12–18); to those in Gideon (30:22–28); and before Alma and the chief judge (30:30–55). He informs us that Korihor preached the same message each time (cf. 30:30), so that when Alma confronts Korihor, Mormon has already presented Korihor’s main arguments and has him open here with accusations about Nephite priests “glutting on the labors of the people” (30:31). Korihor succeeds in distracting Alma with this line of reasoning and the latter responds defensively to this clearly minor issue, rather than directing his remarks to Korihor’s challenge regarding belief in the coming of Christ. In Mormon’s presentation, the exchange comes off naturally enough that readers are unlikely to notice Alma’s omission of the primary issue.

Alma next shifts to a mode of rhetorical questioning in which Korihor again gets the better of him by responding in direct op position to his expectations:

Believest thou that we deceive this people, that causes such joy in their hearts?

And Korihor answered him, Yea.

And then Alma said unto him: Believest thou that there is a God?

And he answered, Nay. (Alma 30:35–38)

Korihor has caught Alma off guard, but in doing so he inadvertently reminds Alma of the crux of their confrontation, namely, the rationality of belief in Christ’s coming. Alma finally ad dresses this issue by retreating to personal testimony: “I know there is a God, and also that Christ shall come” (Alma 30:39). Al though he has a rational, evidence-based argument to back this up (albeit one derived from his subjective experience and thus non-transferrable to the hard of heart), Alma apparently doesn’t think here to appeal to his own angelic witness (cf. Mosiah 27:11, 15; Alma 9:25-29). What he does do is to continue his rhetorical questioning. But rather than risk Korihor’s defiance again, he answers presumptively on his challenger’s behalf: “Believest thou that these things are true? Behold, I know that thou believest, but thou art possessed with a lying spirit” (30:42).

In the end, Alma carries the day but only because Korihor slips and, in his arrogance, cavalierly promises to believe in God if Alma can produce a sign. Once Korihor is struck dumb, he con fesses his apostasy, his short-lived converts are reclaimed, and Alma’s standing before the people is confirmed. But Alma must have been keenly aware that he had been vindicated only by a miracle, and one can hardly rely on divine intervention to end every argument.Korihor’s challenge regarding the rationality of belief in future events has gone unanswered, and Alma surely reflected upon his inadequate response repeatedly, working through the es prit de l’escalier of what he should have said, and awaiting an op portunity for rebuttal.

The Zoramite Situation as Narrative Context

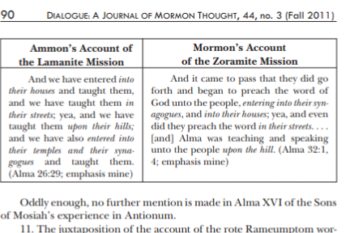

| Ammon’s Account of the Lamanite Mission | Mormon’s Account of the Zoramite Mission |

| And we have entered into their houses and taught them, and we have taught them in their streets; yea, and we have taught them upon their hills; and we have also entered into their temples and their synagogues and taught them. (Alma 26:29; empha sis mine) | And it came to pass that they did go forth and began to preach the word of God unto the people, entering into their synagogues, and into their houses; yea, and even did they preach the word in their streets…. [and] Alma was teaching and speaking unto the people upon the hill. (Alma 32:1, 4; emphasis mine) |

Within Mormon’s single chapter of Alma XVI, the aftermath of the Korihor trial, then, is the background from which Alma mounts a preaching tour to the Zoramites, a community of Nephite dissenters among whom the silent and defeated Korihor went to dwell but where he was “run upon and trodden down, even until he was dead” (Alma 30:59). The Zoramites have settled in a land bordering on Lamanite territory, and many fear that they will enter into a military alliance with the Nephites’ long-standing enemies. So Alma, encouraged by the recent missionary success of the sons of Mosiah’s tour among the Lamanites,musters an eight-man preaching team, consisting of himself, two of his sons, three of the sons of Mosiah, his former preaching companion Amulek, and their convert Zeezrom. Collectively, they have had decades of experience in preaching to the hard of heart, to those who “because of unbelief . . . could not understand the word of God” (Mosiah 26:3). But even so, they are “astonished beyond all measure” (Alma 31:19) when they discover the Zoramites’ innovative and defiant manner of worship. Once a week, believers climb, one at a time, up to a narrow platform called the Rameumptom in the middle of their synagogues, and recite a prayer thanking God for separating them from their wayward brethren: “Holy God . . . we believe that thou hast elected us to be thy holy children; and also thou hast made it known unto us that there shall be no Christ. . . . Thou hast elected us, that we may not be led away after the foolish traditions of our brethren, which doth bind them down to a belief of Christ, which doth lead their hearts to wander far from thee, our God” (Alma 31:16–17).

Alma’s primary reaction to this prayer is concern for the Zoramites’ apostasy, but he is grieved as well because of their excessive pride, that “their hearts were set upon gold, and upon silver, and upon all manner of fine goods” (31:24–26). Alma’s intent in this missionary endeavor is to reclaim the separatist Zoramites, “bringing them again unto [God] in Christ” (31:34), and he prays on behalf of his companions that they might have strength in their anticipated afflictions, success in their endeavors, and wisdom in their teaching approach.

After a laborious struggle to find an audience for their message, the missionary team begins to meet with success among the poor class of the people. Mormon reports that “a great multitude” of “the poor in heart, because of their poverty as to the things of the world” (Alma 32:4), assembled where Alma was preaching, and their spokesman approached with a particular concern: “Behold, what shall these my brethren do, for they are despised of all men because of their poverty, yea, and more especially by our priests; for they have cast us out of our synagogues . . . and we have no place to worship our God; and behold, what shall we do?” (32:5) When the destitute, despised inhabitants of Antio-num come to the missionaries, they, like Alma, are troubled by the rampant materialism that has made their lives miserable. But they do not consider themselves apostates. They fully subscribe to Zoramite beliefs about divine election and the foolishness of looking forward to Christ. Indeed, they worry that their salvation might be forfeit since they have been barred, on account of their poverty, from participating in the Zoramite practice of ritual prayer. The congregation that has gathered certainly knows who Alma is and what he is likely to say, so it must have been out of sheer desperation that they approached him to ask “What shall we do?” They are not interested in learning about Christ, the God of the Nephites; rather they fret, “Our priests . . . have cast us out of our synagogues . . . and we have no place to worship our God” (32:5; emphasis mine).

All of this means that the one message Alma and his companions have come to preach is precisely what the multitude is unwilling to hear. They may be poor in heart, but they are still Zoramites, who have explicitly and emphatically rejected teachings about Christ. Alma recognizes an opportunity: “He beheld with great joy; for he beheld that their affliction had truly humbled them and they were in a preparation to hear the word” (Alma 32:6). But from his recent encounter with Korihor, as well as from the discourse that follows, it is clear that he also recognizes the delicacy of the situation and the rhetorical expertise required to bring this preparatory state to religious awakening. Amulek later suggests that Alma thought through his preaching strategy in advance, considering—in broad strokes at least—how he might “prepare [the Zoramites’] minds” to receive a message about the Son of God (34:3).

Like any good missionary, Alma looks for common ground upon which to base an appeal, much as the sons of Mosiah did among the Lamanites (Alma 18:22–33, 22:5–11), but the objectives of the two parties are nearly irreconcilable: The multitude want to know how they can return to worshiping their God (in a manner that Alma finds reprehensible), while Alma fervently de sires to bring them back into the Nephite religious tradition (which centers upon a deity whom they have decisively abandoned). Although hostile to Christianity, the Zoramites nevertheless believe in the need for redemption and the possibility of revelation (cf. 31:16–17), and they appear to accept at least some of the brass plates’ scriptures as authoritative (cf. 33:12–13). Alma will eventually span the divide that separates them through an astute appeal to the writings of Zenos.

Alma’s Discourse on Faith in Christ

In the much-beloved discourse that follows, found at the heart of Mormon’s Alma XVI (or in contemporary chapters 32–33), Alma demonstrates the very finesse that he seemed to lack in his earlier encounter with Korihor. With a tender and versatile rhetoric (and undoubtedly aided by the wisdom that he had prayed for God to provide), Alma reaches out to the spiritual and emotional concerns of his audience. He speaks with the utmost circumspection throughout, careful to not raise antagonisms or otherwise ignite contrary opinions in the delicate process of challenging deeply held, albeit erroneous, convictions. The display of rhetorical skills that he brings to the task is nothing less than remarkable.

Listening Reflectively. Alma listens carefully enough to the Zoramites’ initial inquiry to repeat it back to them accurately: “Be hold, thy brother hath said, What shall we do—for we are cast out of our synagogues, that we cannot worship our God” (Alma 32:9). In doing so, he communicates that he, unlike the Zoramite elite, values not only his listeners’ concerns but also their dignity: “Their souls are precious, and many of them are our near brethren” (31:35).He further substantiates this respect by inviting them to consider with him both the implications of their dilemma and the hint of a possible way out: “Behold I say unto you, do ye suppose that ye cannot worship God save it be in your synagogues only? And moreover, I would ask, do ye suppose that ye must not worship God only once in a week?” (32:10–11). Alma evidently has a response in mind, but he wants to help his listeners work their way to it with him. In the process, he will keep their attention by continuing to use their question to shape his remarks, recalling it twice more—first, in introducing an experiment in faith (32:24), and again, before quoting several scriptural witnesses (33:2).

Redefining the Situation. Alma encourages the Zoramites to see their current misfortune as a potential asset. He offers hope where they have seen only despair: “I say unto you, it is well that ye are cast out of your synagogues, that ye may be humble, and that ye may learn wisdom” (Alma 32:12; emphasis mine). Likewise, he recasts the value of their reduced social status, identifying their poverty and oppression as spiritual benefits: “blessed are ye; for a man sometimes, if he is compelled to be humble, seeketh repentance” (32:13; emphasis mine). Alma continues in this indirect fashion to enumerate the familiar gospel principles of faith, repentance, baptism—though not explicitly here in the name of Christ—and enduring to the end.Very early in his response, then, he is also subtly redefining the Zoramites’ question itself, from “What shall we do . . . [that we might worship]?” to “What shall we do . . . [that we might obtain salvation]?”

Easing into the Heart of the Matter. Alma addresses the Zoramites’ question about worship without speaking directly of the Rameumptom. He has no interest in debate (his encounter with Korihor had manifested its ineffectiveness) or in provoking his listeners to defend their beliefs. Instead he appeals, ever so gently, to core gospel principles that he knows they had once been taught, hoping to rekindle a spiritual spark from embers long dormant. When Alma does introduce these means of salvation, he does so only hypothetically, drawing no attention whatever to the fact that these appeals actually comprise the solution for which the impoverished Zoramites have been looking. Alma merely offers a glimpse and then retreats. Rather than calling his listeners to repentance or charging them to be baptized, he speaks instead of the blessed state of “he that believeth in the word of God” (Alma 32:16).

A few verses later Alma speaks again of God’s word, this time alluding to a passage from Zenos that he will eventually quote at length: “And now, behold, I say unto you, and I would that ye should remember, that God is merciful unto all who believe on his name; therefore he desireth, in the first place, that ye should believe, yea, even on his word” (Alma 32:22; emphasis mine; cf. 33:4–11). With the simple addition of “I would that ye should remember,” Alma has put into play a clever ambiguity. He is either asking the Zoramites to keep the idea of God’s mercy in mind for the remainder of his discourse, or else he is calling to mind a particular text that he expects to be familiar to his audience. Either way, when he gets to the quotation of Zenos (which describes God as merciful six times in eight verses [cf. 33:4–11]), his listeners will have a flush of affirmation and will find the prophet’s words resonant without particularly noticing why.Alma is adeptly maneuvering toward the possibility of his listeners’ subsequent assent.

Note here also how Alma again suggests and retreats. As soon as he puts forward the idea (not included in Zenos though picked up later by Amulek; cf. Alma 34:15) that “God is merciful unto all who believe on his name,” he modifies it with “yea, even on his word.” Alma, it appears, has a very particular word in mind here—a name, in fact—that he wants the Zoramites to remember but which he is deliberately leaving unsaid. He is executing a subtle transition, from the word of God in v. 16, to this name/word in v. 22, to his own words in v. 27, and finally to a particular though again unspecified word (as we will see below), in v. 28.

Encouraging the Zoramite Poor to Act for Themselves. Alma implies, ever so discreetly, that his listeners need neither the Zoramite elite nor their mode of worship to be “blessed,” that is, to be in a right relationship with God (he repeats this word eight times in four verses [Alma 32:13–16]). He invites them to imagine the superiority of those who humble themselves to those who are compelled to be humble, tacitly encouraging them to aspire to the former. Later, in an aside, he attempts to flatter the impoverished Zoramites into such autonomy: “I verily believe that there are some among you who would humble themselves, let them be in whatsoever circumstances they might” (32:25). He urges them not just to reenvision their situation but to take action to change it: “Awake and arouse your faculties . . . exercise a particle of faith . . . desire to believe . . . give place for a portion of my words” (32:27).

Teaching Them How to Act for Themselves. Alma not only encourages his listeners’ religious autonomy from the Zoramite elite, but he also instructs them on how to achieve it. Ever mindful of their prejudice against belief in the coming of Christ, he outlines an experiment by which they can come to a knowledge of spiritual truth for themselves.

Now, we will compare the word unto a seed. Now, if ye give place, that a seed may be planted in your heart, behold, if it be a true seed, or a good seed, if ye do not cast it out by your unbelief, that ye will resist the Spirit of the Lord, behold, it will begin to swell within your breasts; and when you feel these swelling motions, ye will begin to say within yourselves—It must needs be that this is a good seed, or that the word is good, for it beginneth to enlarge my soul; yea, it beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me. Now, behold, would not this increase your faith? (Alma 32:28–29; emphasis mine)

Alma introduces this seed metaphor in the broadest of terms. But as suggested above, he is not being general here; there is, in fact, one very particular word that he is encouraging his listeners to plant in their hearts. So as not to arouse their prejudice, Alma never mentions the name/word that remains his focus throughout; he continues, instead, to develop the metaphor, instructing his listeners on how to nourish the seed by applying their faith and patience.

After drawing on scriptural testimony, Alma summarizes his message with a final appeal to the Zoramites’ ability to affect their own spiritual good: “And now, my brethren, I desire that ye shall plant this word in your hearts, and as it beginneth to swell even so nourish it by your faith. And behold, it will become a tree, springing up in you unto everlasting life. . . . And even all this can ye do if ye will (Alma 33:23; emphasis mine).

Preempting Objections. Into his discourse, Alma incorporates responses to the Zoramites’ arguments against belief in the coming of Christ. Again, he is not interested in debating these points, but he does want to put the potential issues to rest. By referring to Moses’s testimony concerning the Son of God, he dismisses any claim that belief in Christ violates that prophet’s teachings. (See note 5.) He counters the assertion that one can know nothing about things which are to come (cf. Alma 31:22), by conceding, first, that “faith is not to have a perfect knowledge of things,” and then by explaining that one can, in fact, come to know of unseen things for oneself by exercising that faith (32:21, 27).

From his opening allusion and use of similar wording, Alma manifests that he is here presenting his worked-out rebuttal to Korihor’s challenge regarding the rationality of belief:

| Alma | Korihor |

| Yea, there are many who do say: If thou wilt show unto us a sign from heaven, then we will know of a surety; then we shall believe. Now I ask, is this faith? . . . Faith is not to have a perfect knowl edge of things; therefore if ye have faith ye hope for things which are not seen, which are true (Alma 32:16-17, 21; empha sis mine). | O ye that are bound down under a foolish and a vain hope, . . . why do ye look for a Christ? for no man can know anything of that which is to come. How do ye know of their surety? Behold, ye cannot know of things which ye do not see . . . and except ye show me a sign, I will not believe. (Alma 30:13, 15, 48; emphasis mine) |

This cluster of ideas—of knowing of a surety, hoping, believing in things not seen, and believing only after signs have been shown—is found only in these two scriptural episodes which have been linked by Mormon in a single chapter. Alma has come to realize that as long as one’s heart is not hardened against belief, spiritual understanding is indeed attainable through individual empirical experience; the growth of a seed is, after all, a largely hidden, yet completely natural, universally applicable process. To Korihor’s argument that “ye cannot know of things which ye do not see,” Alma finally responds:

And now, behold, because ye have tried the experiment, and planted the seed, and it swelleth and sprouteth, and beginneth to grow, ye must needs know that the seed is good. And now, behold, is your knowledge perfect? Yea, your knowledge is perfect in that thing . . . and this because ye know, for ye know that the word hath swelled your souls, and ye also know that it hath sprouted up, and that your understanding doth begin to be enlightened, and your mind doth begin to expand. O then, is this not real? I say unto you, Yea. (Alma 32:33–35)

Alma is still answering his own rhetorical questions, but he has now provided rational justification for belief in the future coming of Christ.

Appealing to Scriptural Authority. In keeping with the Mosaic prescription of “two or three witnesses” (cf. Deut. 19:15; 2 Ne. 11:2–3), Alma now appeals to scriptural testimony to buttress the truth of his message. In doing so, he intentionally transfers the authority inherent in these scriptures to his efforts to instruct the Zoramites. Here, too, Alma eases his listeners into the heart of the matter, testing the water with a couple of oblique allusions.

He begins by incorporating Nephi’s interpretation of his father’s vision of the tree of life and its “most precious fruit” into his experiment in faith (Alma 32:40–42; cf. 1 Ne. 8:11, 15:36). As Alma surely knows—and perhaps hopes that the Zoramites will re call—Nephi’s understanding of the meaning of this tree is embedded in a divine testimony of the mission of the Son of God (cf. 1 Ne. 11:6–23). Alma’s next allusion—that in feasting upon this fruit his receptive listeners will “hunger not, neither shall [they] thirst”—similarly takes its context from a scriptural testimony of salvation, this time in the work of the chosen servant described by Isaiah (32:42; cf. Isa. 49:8–10).

After completing his explanation of the experiment in faith, Alma returns at last to the Zoramites’ opening inquiry, about how they are to worship God, by reciting an extended passage from Zenos, a prophet from the brass plates. The quotation that follows fits Alma’s rhetorical needs perfectly: It begins by addressing the Zoramites’ question (its theme is the efficacy of personal prayer) and advances toward Alma’s ultimate objective of bearing effectual testimony of the Son of God. Shifting away from his studied indirection, Alma begins now to make his purpose clear: “Behold, ye have said that ye could not worship your God because ye are cast out of your synagogues. But behold, I say unto you, if ye suppose that ye cannot worship God, ye do greatly err, and ye ought to search the scriptures. . . . Do ye remember [that word again!] to have read what Zenos, the prophet of old, has said concerning prayer or worship?” (Alma 33:2–3)

Note how Alma ingeniously conflates the terms “prayer” and “worship” here (just as he did previously with “name” and “word”). The Zoramite poor have asked specifically about the latter, and Alma—drawing on Zenos—instructs them that spontaneous prayer is worship and that it can be offered anywhere: in the wilderness, in cultivated fields, or in the privacy to be found in either closets or crowds. As he repeats Zenos’s refrain “thou didst hear me,” Alma is also implicitly arguing against the need for priestly mediation in one’s access to God.

Until this point, Alma has carefully avoided a direct confrontation over belief in Christ. He has spoken at length about planting “the word,” but so far has used the term only in ambiguous (and thus deliberately inoffensive) ways. But now, in quoting Zenos’s concluding verse, Alma inches toward theological specificity: “And it is because of thy Son that thou hast been thus merciful unto me . . . for thou hast turned thy judgments away from me, because of thy Son” (Alma 33:11). There is still no mention of the name/word, but the identity of this particular son of God cannot be lost on his audience.

After concluding the passage from Zenos, Alma elaborates upon this very point:

Do ye believe those scriptures which have been written of them of old? Behold, if ye do, ye must believe what Zenos said; for behold he said: Thou hast turned away thy judgments because of thy Son. Now behold, my brethren, I would ask if ye have read these scriptures.If ye have, how can ye disbelieve on the Son of God? For it is not written that Zenos alone spake of these things, but Zenock also spake of these things—For behold, he said: Thou art angry, O Lord, with this people, because they will not understand thy mercies which thou hast bestowed upon them because of thy Son. And now, my brethren, ye see that a second prophet of old has testified of the Son of God. . . . But behold, this is not all; these are not the only ones who have spoken concerning the Son of God. Behold, he was spoken of by Moses. (Alma 33:12–19)

Alma’s primary purpose in incorporating the teachings of Zenos, Zenock, and Moses is to demonstrate their testimonies of Jesus Christ. But he is also making brilliant use of these scriptures to appeal to the particular conditions of his listeners. He uses the Zenos quotation, for example, not only in subtle criticism of Rameumptom worship but also as a remedy for his listeners’ particular afflictions.

It is remarkable just how comparable Zenos’s personal situation is to the context of the Zoramite mission. The opening verses apply directly to the situation at hand from the perspective of Alma and his missionary companions: “Thou art merciful, O God, for thou hast heard my prayer . . . yea, thou wast merciful when I prayed concerning those who were mine enemies, and thou didst turn them to me” (Alma 33:4; emphasis mine). The analogous prayer is when Alma prays for success in reclaiming the Zoramite dissenters (31:26–35). Note that Zenos’s prayer thanks God for turning these enemies not from the speaker—as at Psalms 9:3 or 56:9—but to him. And this is literally what has occurred, and what needed to occur, and what presumably could only have occurred because of the grace of God, when the multitude approached Alma with their question about worship. Had the Zoramites turned from Alma, he would have had no opportunity to teach them.

Subsequent verses apply directly to the situation of Alma’s listeners.Verse 8 includes this indirect criticism of the Zoramite mode of worship: “Thou art merciful unto thy children when they cry unto thee, to be heard of thee and not of men” (Alma 33:8, empha sis mine). The Rameumptom prayer was certainly designed as public display and an iteration of self-importance rather than as the penitent submission Zenos describes. Alma elsewhere explains as much when he instructs his son Shiblon, who had been a member of the missionary team to Antionum: “Do not pray as the Zoramites do, for ye have seen that they pray to be heard of men” (38:13, emphasis mine).

Verses 9 and 10 continue to describe the situation of the Zoramite poor: “Yea, O God, thou hast been merciful unto me, and heard my cries in the midst of thy congregations [i.e., not from the Rameumptom, from which they had been excluded]. Yea, and thou hast also heard me when I have been cast out and have been despised by mine enemies.” In approaching Alma, the spokesman for the Zoramites used these very words to describe their condition: “Behold, what shall these my brethren do, for they are despised of all men because of their poverty, yea, and more especially by our priests; for they have cast us out of our synagogues . . . and we have no place to worship our God” (Alma 32:5). And finally, v. 11 describes the common condition of both the Nephite missionaries and their Zoramite interlocutors: “And thou didst hear me because of mine afflictions and my sincerity; and it is because of thy Son that thou hast been merciful unto me.” (See Alma 31:31– 33 for the missionaries’ afflictions, and 32:6, 24 for the Zoramites’; the sincerity of both groups is self-evident.)

When Alma later quotes Zenock as saying, “Thou art angry, O Lord, with this people, because they will not understand thy mercies which thou hast bestowed upon them because of thy Son,” he is not just linking Zenock’s testimony with Zenos’s in affirming the reality of the Son, but he is also condemning this people, the Zoramites, for their prideful rejection of Christ. He avoids the direct confrontation that such an accusation would otherwise bring, by voicing it in Zenock’s words and by focusing attention on its testimony of Jesus rather than on the Lord’s anger at its rejection. With this one brass-plates’ verse, Alma both condemns those of his listeners who “will not understand” and simultaneously invites those willing to humble themselves to receive the Lord’s mercies.

In appealing to Moses, Alma refers to a narrative rather than a quotation, but again he demonstrates the prophet’s testimony of the Son of God and also uses the scriptural passage to draw out a reading of the Zoramites’ current condition. Like the children of Israel, most of the Zoramites are lacking in understanding and are so hard of heart that they will not look to the Son of God (or to his “type . . . raised up in the wilderness”) to be healed (cf. Alma 33:18–20). Where Alma previously let the indirection of the Zenock passage stand, he now makes the scriptural comparison explicit: “O my brethren, if ye could be healed by merely casting about your eyes . . . would ye not behold quickly, or would ye rather harden your hearts in unbelief . . . that ye might perish?” (Alma 33:21).

Alma’s discourse culminates in the full gospel message, as he urges his audience to “begin to believe on the Son of God, that he will come to redeem his people, and that he shall suffer and die to atone for their sins; and that he shall rise again from the dead, which shall bring to pass the resurrection, that all men shall stand before him, to be judged at the last and judgment day, according to their works” (Alma 33:22). But Alma has still not uttered the one word most likely to offend Zoramite religious sensibilities; he leaves its articulation to Amulek.

Preaching in Tandem. Alma and Amulek work in Antionum as a teaching team, much as they had in Ammonihah. As we have seen, Alma has prepared the minds of his audience through the simultaneous emotional and theological development of ideas, and Amulek’s task is to bring this strategy to its intended conclusion. He begins with a summary of Alma’s message, finally making explicit the word that Alma has held back, which he ties to his listeners’ own unstated concern:

My brethren, I think that it is impossible that ye should be ignorant of the things which have been spoken concerning the coming of Christ, who is taught by us to be the Son of God. . . . And as ye have desired of my beloved brother that he should make known unto you what ye should do, because of your afflictions . . . he hath exhorted you unto faith and to patience—Yea, even that ye would have so much faith as even to plant the word in your hearts, that ye may try the experiment of its goodness. And we have beheld that the great question which is in your minds is whether the word be in the Son of God, or whether there shall be no Christ. And ye also behold that my brother has proved unto you, in many instances, that the word is in Christ unto salvation. (Alma 34:2–6; emphasis mine)

Amulek goes on to explain the necessity of the Atonement and to expound on Jesus’s role in the “great and eternal plan of redemption” (Alma 34:8–16). He reiterates Alma’s admonition that the Zoramites exercise faith and patience in experimenting upon the word (32:41–43; 34:3–4, 17), speaking the name of Christ several times more (34:8, 37–38). He reinforces Alma’s teachings on the centrality of personal prayer by offering his own exhortation based on the repetition of Zenos’s phrase “cry unto him” and including the prophet’s distinctive usage of wilderness, field(s), and closet(s), the only aspects of Zenos’s psalm that Alma had not already incorporated in some way (cf. 34:18–27). He urges the Zoramites to “continue in prayer” and to attend to the needy as a return to observing the performances of the church (34:19, 28–29; cf. Mosiah 18:23, 27; Alma 31:10).

Amulek concludes with an extended and clarion call to repentance, once again following up on Alma’s earlier indirection. Compare Alma’s “for a man sometimes, if he is compelled to be humble, seeketh repentance” (32:13) to Amulek’s: “And now, my brethren, I would that, after ye have received so many witnesses, seeing that the holy scriptures testify of these things, ye come forth and bring fruit unto repentance. Yea, I would that ye would come forth and harden not your hearts any longer; for behold, now is the time and the day of your salvation; and therefore, if ye will repent and harden not your hearts, immediately shall the great plan of redemption be brought about in you” (Alma 34:30– 31). Alma and Amulek are working together here to empower the Zoramite poor to “work out [their] salvation with fear before God, and . . . no more deny the coming of Christ” (34:37).

The Aftermath of Alma’s Preaching to the Zoramites

In concluding Alma XVI, Mormon reports the results of the missionaries’ efforts among the Zoramites: “Those who were in favor of the words which had been spoken by Alma and his brethren were cast out of the land; and they were many; and they came over . . . into the land of Jershon” (Alma 35:6), where they were received and given an inheritance by the people of Ammon. This series of events, in turn, stirred up the remaining Zoramites in anger and resulted in their military alliance with the Lamanites. Within a year, a tremendous battle ensued, just as Alma had feared, such that “the number of the dead was exceedingly great” (44:21), with a consequence that the Zoramites essentially drop out of Nephite history.

Ironically, then, and rather problematically, Alma’s missionary tour directly caused the very scenario it was intended to avert (cf. 31:4–5). But as it turns out, this, too, was foretold by Zenos: “Yea, O God, thou hast been merciful unto me. . . . Yea, thou didst hear my cries, and wast angry with mine enemies, and thou didst visit them in thine anger with speedy destruction . . . . And it is because of thy Son that thou hast been thus merciful unto me . . . for thou hast turned thy judgments away from me, because of thy Son” (Alma 33:9–11). Zenos’s prophecy here underscores the message that the warfare that transpired was indeed God’s will, thereby eliminating any culpability that might be assessed to Alma and his preaching companions.It also specifically identifies the upcoming “speedy destruction” as God’s judgment, and thus redefines the missionaries’ task in Antionum as harvesting the righteous before the wicked are inevitably overtaken, much like what had occurred in Ammonihah.

Those Zoramite poor who hearkened to Alma’s message, ex perimented upon the word, and found mercy from their faith in the coming of Christ, were delivered not only from their sins but also from the battle that obliterated their former co-dissenters. The suddenness of the Zoramite downfall echoes Mormon’s summary of Korihor’s demise: “And thus we see the end of him who perverteth the ways of the Lord; and thus we see that the devil will not support his children at the last day, but doth speedily drag them down to hell” (30:60).

What, then, are we to make of all this? How, precisely, can attending to context affect our understanding of the Book of Mormon? There is nothing wrong with asserting simply and sincerely from a reading of Alma 32 that “faith is like a little seed: if planted, it will grow,”but we are mistaken if we think that this is all Alma has to offer. In expanding from the experiment-in-faith pericope (Alma 32:26–32) to the context of Alma’s entire discourse (32:7– 33:23), for example, we can recognize that his general teachings on faith become increasingly focused on Jesus Christ and that he draws upon scriptural witnesses to support this testimony. As we bring in Mormon’s narrative to supplement Alma’s words, considering the audience and situation that Alma is addressing (31:1–32:6), we come to realize both why he adopted this rhetoric of indirection for the Zoramites and how expertly and gracefully he employed it. (Indeed, it may serve as a model for how to communicate unwelcome truths without provoking hostility.)As we expand our circle of meaning to include Amulek’s words as well (34:1–41), we come finally to understand the specific meaning of the word that is to be compared “unto a seed” and the precious fruit available to those who “exercise [their] faith unto repent ance” and “take upon [them] the name of Christ” (34:17, 38).

Adding the context of the Korihor episode, as Mormon surely intends, not only from his original chapter division but also from common themes and phrasing, we see the development of one called to be an instrument in God’s hands (cf. Alma 29:9) and the unfolding of responses to challenges to faith. Neither do Mormon’s intended interpretive contexts for Alma’s mission to the Zoramites end at the boundaries of Alma XVI. He leaves hints throughout—distinctive phrases, narrative details, repeated words— that earlier events also offer significant material for illumination, including Alma’s and the sons of Mosiah’s youthful anti-Christian preaching and subsequent conversion (Mosiah 26–27), Alma’s labors with Amulek in Ammonihah (Alma 8:8–15:2), and the sons of Mosiah’s mission among the Lamanites (Alma 17:5–27:15). Teachings of earlier prophets—Zenos, Zenock, and Moses, certainly, but also Lehi, Nephi, Jacob, Abinadi, and others—come into play as well through intentional quotation and allusion.

In reading the Book of Mormon, the consequence of ignoring these multiple contexts is a limitation rather than a danger. By its own admission, the book is plain, clear, and didactic. There is little chance of serious misreading and little ambiguity in its central teaching of “how to come unto [Christ] and be saved” (1 Ne. 15:14; cf. Moro. 10:32). But the Book of Mormon is also much richer than is generally supposed even by its adherents (to say nothing of its many detractors). There is an integrated coherence and profound wisdom here that are too often obscured by our attempts to make its truths accessible, whether in contemporary chapter divisions and versification or in the rush to extract eternal principles from its lengthy sermons and intricate narratives. Before we analyze what Alma’s sermon on faith means to us, it would be well to imagine what it meant to his original audience and also to Alma himself, in light of his recent experiences. By studying specific incidents within their broader contexts—especially those indicated by Mormon’s arrangement of his material—readers may be able to find more insight and coherence in this extraordinary book than they had previously expected.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue