Articles/Essays – Volume 12, No. 2

Elijah Abel and the Changing Status of Blacks Within Mormonism

On the surface it was just another regional conference for the small but troubled Cincinnati branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on a summer day in June 1843. Not unlike other early branches of the Church, the Cincinnati congregation had a number of problems, including internal dissension and just plain “bad management.” Presiding over this conference was a “Traveling High Council” consisting of three Mormon apostles.[1] As the visiting council probed the difficulties plaguing the Cincinnati Saints, its attention was drawn to the activities of Elijah Abel, a unique member of the branch. Abel, a black Mormon Priesthood holder, found himself under fire because of his visibility as a black Mormon. Apostle John E. Page maintained that while “he respects a coloured Bro, wisdom forbids that we should introduce [him] before the public.” Apostle Orson Pratt then “sustained the position of Bro Page” on this question. Apostle Heber C. Kimball also expressed concern about this black priesthood holder’s activities. In response, Abel “said he had no disposition to force himself upon an equality with white people.” Toward the end of the meeting, a resolution was adopted restricting Abel’s activities. To conform with the established “duty of the 12 … to ordain and send men to their native country Bro Abels [sic] was advised to visit the coloured population. The advice was sanctioned by the conference. Instructions were then given him concerning his mission.”[2]

This decision represents an important turning point not only for Elijah Abel but for all Mormon blacks. For the first time race was used as a criterion for limiting the activities of a black Latter-day Saint. Until 1843, Abel had suffered no known racial discrimination despite his status as one of Mormonism’s few black members. His membership in the Church went back to 1832 when he was baptized by Ezekiel Roberts.[3]

Abel was born on July 25,1810 in Maryland and later migrated to Mormonism’s headquarters in Kirtland, Ohio.[4] Within four years of his conversion, he was ordained an Elder in the Melchizedek Priesthood.[5] By June 1836, he was listed, along with a number of other Mormon priesthood holders, as a duly licensed “minister of the gospel.”[6] As a member in good standing, he was promoted in the Melchizedek Priesthood to the rank of Seventy in December 1836[7] and received a patriarchal blessing in the same year. This ordinance, performed by Joseph Smith, Sr., father of the Mormon Prophet, proclaimed that Abel was “ordained an Elder and annointed to secure thee against the power of the destroyer.” In this blessing were apparent allusions to Abel’s unusual status as one of Mormonism’s few black members. In contrast to his white fellow Saints who were often declared descendants of a particular biblical lineage—usually Joseph or Ephraim—Abel was not assigned such a lineage. Instead, he was proclaimed “an orphan.” Finally, this blessing promised, “Thou shalt be made equal to thy brethren, and thy soul be white in eternity and thy robes glittering.”[8]

Like many of his white male priesthood brethren, Abel served as a missionary for the Church during the late 1830s. The field of Abel’s missionary labors included New York state and Canada. Little is known about his success as a missionary, but his activities did generate controversy. According to one account, Missionary Abel was accused by the non-Mormon residents of St. Lawrence County, New York, of murdering a woman and five children. “Handbills were pasted up in every direction . . . and a great reward was offered for him.” Apparently Abel was successful in refuting these charges, leaving the community “unmolested.”[9] While in Canada, Abel also ran into difficulties—this time with his fellow Saints. He was challenged on “some of his teachings, etc.” Abel proclaimed “that there would be Stakes of Zion in all the world, that an elder was a High Priest and he had as much authority as any H.P.” He was also accused of “threatening to knock down” a fellow elder. Abel reportedly rationalized this behavior, declaring that “the elders in Kirtland make nothing of knocking down one another.” The topic of Abel’s behavior came up in a meeting of church leaders, which included Joseph and Hyrum Smith and Sidney Rigdon as well as the Quorum of Seventies, but no disciplinary action was taken.[10]

Abel had not been the only black Mormon to create controversy within the Church during the 1830s. “Black Pete,” through his activities in Kirtland as a self styled “revelator,” attracted notoriety both within and outside Mormonism.[11] Unfortunately, little is known about his background. According to one account, Pete migrated to Ohio from Pennsylvania where he had been born to slave parents.[12] After his arrival in Ohio, Pete joined the Mormon movement in late 1830 or early 1831. This “man of colour” was described in two other accounts as “a chief man, who [was] sometimes seized with strange vagaries and odd conceits.”[13] On at least one occasion Pete fancied he could “fly” and

took it into his head to try his wings; he accordingly chose the elevated bank of Lake Erie as a starting-place, and, spreading his pinions, he lit on a treetop some fifty feet below, sustaining no other damage than the demolition of his faith in wings without feathers.[14]

There is some confusion over Pete’s other activities among the Saints. According to one reminiscence Pete “wanted to marry a white woman” but Joseph Smith could not get any “revelations” for him to do so.[15] According to another, however, Pete was active at a time when Joseph Smith and other church authorities were not around. Whatever the case, the Mormon Prophet brought forth in February 1831 a revelation condemning false revelators such as Black Pete. Smith was told that only certain individuals “appointed unto you” were authorized “to receive revelations.”[16] Thereafter, several of the self-appointed revelators, possibly including Pete, were “tried for [their] fellowship” and “cut off” from the Church.[17]

Despite the controversy caused by the Mormon activities of both Black Pete and Elijah Abel, Latter-day Saint leaders did not establish a subordinate ecclesiastical place for black people within Mormonism during the 1830s. The number of free blacks casting their lot with the Saints was very small. According to Apostle Parley P. Pratt, “one dozen free negroes or mulattoes never have belonged to our society in any part of the world, from its first organization [in 1830] to this date, 1839.”[18] As for the secular status of black slaves in Missouri and the slaveholding South—regions of increased Mormon activity during the 1830s—the Church in 1835 officially adopted a strong anti-abolitionist position which assented to the servile conditions of these blacks.[19] At the same time, concerned Latter-day Saints maintained a basic dislike for slavery as a viable institution for themselves. This attitude, originally articulated in the Book of Mormon but muted during the 1830s, was still evident throughout this period. By expressing antipathy for both slavery and antiabolitionism, in turn or even concurrently, the Saints were able to avoid internal divisions over slavery and to minimize Mormon involvement in the increasingly acute national controversy.[20]

Thus, in 1839 when Elijah Abel migrated from Kirtland to Nauvoo, Illinois, he was still accepted in full fellowship both within the Church and the larger community. As an active Latter-day Saint, Abel participated in at least two baptisms for the dead following his arrival in Nauvoo.[21] He earned his livelihood as a carpenter and joined with six others who described themselves as “the House Carpenters of the Town of Nauvoo.” In February 1840 the group published a small “book of prices” which outlined the uniform rates to be charged by these Nauvoo carpenters.[22] In addition, Abel, according to his own recollections, was “appointed” by Joseph Smith “to the calling of an undertaker in Nauvoo.”[23] In this occupation, Abel was kept busy by the appallingly high number of deaths from malaria and other diseases during the early years of Nauvoo’s settlement.[24]

While in Nauvoo, Abel apparently had close contact with the Joseph Smith family. According to one account, Abel was “intimately acquainted” with the prophet and lived in his home.[25] Abel recalled being present at the bedside of Patriarch Joseph Smith, Sr. “during his last sickness” in 1840. The following year Abel, along with six other Nauvoo Mormons attempted to rescue Joseph Smith after his arrest for earlier difficulties in Missouri.[26]

In 1842 Abel moved for unknown reasons from Nauvoo to Cincinnati, where he continued to labor as a carpenter.[27] While in Cincinnati he married a black woman, Mary Ann Adams, and by the time of his migration from Cincinnati to Salt Lake City in 1853, he was the father of three children.[28] Just six months before the June 1843 conference that attempted to limit Abel’s visibility, Joseph Smith apparently alluded to him in a positive way. The prophet declared “Go to Cincinnati . . . and find an educated negro, who rides in his carriage, and you will see a man who has risen by the powers of his own mind to his exalted state of respectability.”[29]

Abel continued to remain active in the affairs of the Cincinnati branch. In June 1845, for example, “Elder Elijah Able [sic] preferred a charge against” three women for their failure to attend church meetings and for “speaking disrespectfully of the heads of the Church.”[30] Nevertheless, the Mormon status of Elijah Abel and all black Latter-day Saints deteriorated after 1840 despite their faithful activity.

In addition to Abel, other Mormon blacks found themselves in conspicuous situations during these years. One such member was Walker Lewis, a barber in Lowell, Massachusetts. Little is known of Lewis’ background other than that he was apparently ordained an Elder by William Smith, the younger brother of the Mormon prophet.[31] As with Abel, Lewis’ role or place within Mormonism was not initially questioned by church officials. Various Mormon apostles visiting Lowell as late as 1844-45 seemed to accept Lewis’ priesthood status.[32] One of these visitors, Apostle Wilford Woodruff, merely observed in November 1844 that “a coloured Brother who was an Elder”—presumably Lewis—manifested his support for the established church leadership during this time of great internal division.[33] By 1847, however, Lewis’ status within the Church was challenged by William L. Appleby who was in charge of Mormon missionary activity in the eastern states. During a visit to Lowell in 1847, Appleby encountered Lewis, and in a terse letter to Brigham Young expressed surprise at finding a black ordained to the priesthood. Appleby asked the Mormon leader if it was “the order of God or tolerated, to ordain negroes to the priesthood … if it is, I desire to know it as I have yet got to learn it.” Unfortunately by the time Appleby’s letter arrived at Winter Quarters, Young was on his way to the Great Basin with the first group of Mormon settlers, and thus was unable to reply in writing to Appleby’s question.[34]

However, by 1849, Brigham Young was willing to assert that all Mormon blacks were ineligible for priesthood ordination. Young’s 1849 statement—one of the earliest known declarations of black priesthood denial—came in response to a question posed by Apostle Lorenzo Snow concerning the “chance of redemption . . . for the African.” Young replied:

[T]he curse remained upon them because Cain cut off the lives [sic] of Abel, to prevent him and his posterity getting ascendency over Cain and his generations, and to get the lead himself, his own offering not being accepted of God, while Abel’s was. But the Lord cursed Cain’s seed with blackness and prohibited them the priesthood, that Abel and his progeny might yet come forward, and have their dominion, place, and blessings in their proper relationship with Cain and his race in the world to come.[35]

Brigham Young’s decision to deny blacks the priesthood was undoubtedly prompted by several factors. Among the most important may well have been the controversy generated in 1846-47 by the flamboyant activities of William McCary, a half-breed Indian-black man referred to variously as the “Indian,” “Lamanite,” or “Nigger Prophet.”[36] The descriptions of McCary are vague and often conflicting, making it difficult to determine his exact activities and relationship to the Latter-day Saint movement. McCary’s origin and occupation are not known. The earliest known account, written in October 1846, claims that Apostle Orson Hyde while at a camp near Council Bluffs, Iowa, “baptised and ordained … a Lamanite Prophet to use as a tool to destroy the churches he cannot rule.”[37]

By late October 1846, McCary shifted his base of operation east to Cincinnati. The Cincinnati Commercial described the exploits of “a big, burley, half Indian, half Negro, formerly a Mormon” who built up a religious following of some sixty members “solemnly enjoined to secrecy” concerning their rites due to their apparent practice of plural marriage.[38] McCary “proclaimed himself Jesus Christ” showing his disciples “the scars of wounds in his hands and limbs received on the cross;” and performed “miracles with a golden rod.”[39] The blessing that he conferred upon his followers reflected at least some knowledge of Latter-day Saint ritual.

Accept this blessing in the name of the Son, Jesus Christ, Mary, the mother, God our Father, our Lord. AMEN. It will preserve yours, yourself, your dead, your family through this life into [the] celestial kingdom, your name is written in the Lamb’s Book of Life, AMEN.[40]

It is not clear whether McCary had any contact with Elijah Abel or any of the other Cincinnati Saints upholding the leadership claims of Brigham Young and the Twelve. Whatever the case, McCary’s Cincinnati-based movement was short lived. By mid-November his following had dwindled to thirty, and by February 1847, McCary himself had left Cincinnati.[41]

McCary returned west to Winter Quarters, Nebraska, joining the main body of Saints under the leadership of Brigham Young in their temporary encampment. Young and others initially welcomed McCary into the Mormon camp where he was recognized as an accomplished musician, entertaining the encamped Saints during the months of February and March 1847.[42] The Saints might have had other uses in mind for McCary. In a somewhat ambiguous statement, John D. Lee, a follower of Young, said that the black Indian “seems to be willing to go according to counsel and that he may be a useful man after he has acquired an experimental knowledge,” and he advised his fellow Saints to “use this man with respect.”[43] By late March 1847, however, McCary had fallen from Mormon favor. What he did to offend Brigham Young is not clear but at a “meeting of the twelve and others” summoned to consider this matter

[William] McCary made a rambling statement, claiming to be Adam, the ancient of days, and exhibiting himself in Indian costume; he also claimed to have an odd rib which he had discovered in his wife. He played on his thirty- six cent flute, being a natural musician and gave several illustrations of his ability as a mimic.[44]

Following this March 1847 meeting, Church leaders expelled McCary from the Mormon camp at Winter Quarters. Subsequently, Apostle Orson Hyde preached a sermon “against his doctrine.”[45]

This was not the end of McCary’s Mormon involvement, although his subsequent activities are even more difficult to trace.[46] It appears, however, that McCary remained active in the area around Winter Quarters and proceeded to set up his own rival Mormon group drawing followers away from Brigham Young.[47] According to a July 1847 account, the “negro prophet” exerted his influence by working “with a rod, like those of old.”[48] By the fall of 1847, McCary was teaching and practicing racial miscegenation in which McCary had a number of women

. . . seald to him in his way which was as follows, he had a house in which this ordinance was preformed his wife . . . was in the room at the time of the proformance no others was admited the form of sealing was for the women to go to bed with him in the daytime as I an informed 3 diforant times by which they was seald to the fullest extent, [sic]

McCary’s activities and this “Sealing Ordinance” caused a negative reaction among those Latter-day Saints in the surrounding community not involved with his sect, particularly the relatives of McCary’s female disciples. One irate Mormon wanted “to shoot” McCary for trying “to kiss his girls.” But McCary, sensing the impending storm, “made his way to Missouri on a fast trot.”[49]

While the whirlwind generated by McCary’s activities upset Brigham Young and other church leaders, the decision to deny blacks the priesthood was probably prompted as much, if not more, by the exposure of the Latter-day Saints to a large number of blacks—both slave and free—following the Mormon migration to the Great Basin. This region’s black population of 100 to 120 individuals, who arrived during the years 1847-49, stood in sharp contrast to the twenty or so blacks that had lived in Nauvoo during the Mormon sojourn there.[50] The sudden appearance of these Great Basin blacks—a significant proportion of whom were slaves— helped to encourage Brigham Young and other church leaders to clearly define both their secular and ecclesiastical status, and that of black people generally. In response, Latter-day Saint leaders not only prohibited blacks from holding the priesthood but also adopted through the Utah territorial legislature a set of antiblack laws that limited the rights and activities of free blacks and gave legal recognition to the institution of black slavery in the territory.[51]

A final factor not to be overlooked as influencing the 1849 Mormon decision to deny blacks the priesthood was the intensification of Mormon antiblack attitudes during the 1840s. The Latter-day Saints became more prone to associate blackness, black counter-figures, and indeed black people with a widening circle of opponents and enemies.[52] While this tendency was certainly evident before Joseph Smith’s death, it became increasingly prominent after Brigham Young’s emergence as the leader of the Saints who migrated West. As Lester E. Bush, Jr. has suggested, Brigham Young was more willing than Joseph Smith to embrace certain antiblack racial concepts and practices prevalent in American society. This, in turn, played a crucial role in the emergence of Mormon black priesthood denial in 1849.[53]

When Elijah Abel migrated from Cincinnati to Utah in 1853, he found that his status within Mormonism had been undermined. While no effort was made to declare Abel’s priesthood authority “null and void” (despite later suggestions to the contrary), Abel was prohibited from participating in certain temple ordinances considered essential for full Mormon salvation. When Abel “applied to President Young for his endowments … to have his wife and children sealed to him,” the Mormon president “put him off” because, according to one account, participation in these ordinances was “a privilege” that the Mormon president “could not grant.”[54] This refusal was ironic in light of Abel’s willingness to contribute his time and labor to the construction of the Salt Lake Temple.[55]

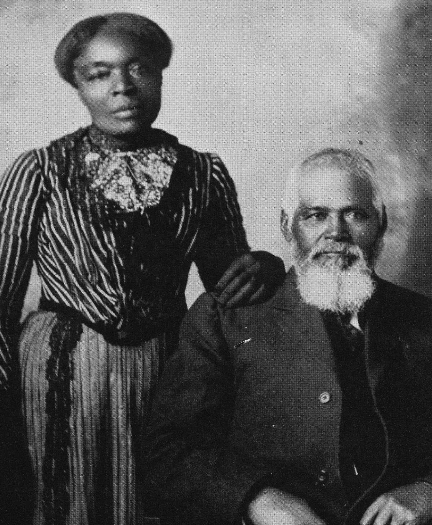

Despite these difficulties, Elijah Abel tried to make the best of his situation. By 1857 he was listed as a member of the Mill Creek Ward in Salt Lake City where he, his wife, and his oldest son, Maroni, were rebaptized like so many other Saints during the “Mormon Reformation” of 1857.[56] In 1877, “Bro Elijah Abel was notified that he was still a member of the Third Quorum” of Seventies.[57] In the meantime Abel’s family continued to grow. At least four daughters and one son were born during the years 1856-1869.[58] Throughout most of the period, Abel continued to support himself and his family as a carpenter.[59] In addition, for a brief period in 1859, he and his wife managed the Farnham Hotel in Salt Lake City.[60] Abel also resided for a very short time during the early 1870s in Ogden, where according to the recollections of one old-time resident the Abel family “went around from ward to ward . . . putting on minstrel shows.”[61]

The period 1855 to 1877 was also marked by difficulty and disappointment for Elijah Abel. On at least two occasions, in 1855 and again in 1864, Abel was listed as delinquent in paying his taxes.[62] Also in 1864 Abel’s son Maroni “was charged before Alderman Clinton with stealing a shaving knife from an emigrant on the Public square.”[63] The Abel family was plagued with further heartache in 1871 when Maroni died while still in his early twenties.[64] Six years later Abel’s wife Mary Ann died of pneumonia at the relatively young age of 46, leaving the aging black priesthood holder to care for himself.[65]

Despite these difficulties, Abel once again renewed his application for his temple endowments to John Taylor, who by 1880 had succeeded Brigham Young as Church president. Taylor submitted Abel’s request to the Council of the Twelve which rendered “a decision unfavorable to Brother Abel.”[66]

Abel was not the only black Mormon trying to secure temple ordinances during this period. Like Abel, Jane Manning James petitioned church leaders on several occasions for her endowments and sealings. The background and experiences of Jane Manning dramatized the changing and, indeed, deteriorating place of blacks within Mormonism.[67] Manning was also a long-time member of the Church. She joined the Mormon movement during the early 1840s while a resident of Wilton, Connecticut. Following her conversion she and eight members of her immediate family migrated to Nauvoo in 1843. Upon her arrival in the Mormon community, Manning became “a member of Joseph Smith’s household” where she stayed until “shortly before” the Mormon prophet’s death. Just before the Mormon abandonment of Nauvoo, she married Isaac James, a free black Mormon who had lived in Nauvoo since 1839.[68] Jane Manning James and her family were among the earliest Saints to migrate west, arriving in the Great Basin in 1847. Like so many Great Basin Mormons, the James family engaged in farming and achieved a fair degree of success. However, Jane and her husband had separated by late 1869 or early 1870.[69] Possibly as a result of this separation, Jane became concerned about her future salvation. Realizing the importance of temple ordinances for future exaltation, she petitioned for the right to receive her sealings and endowments. This was done in a number of requests submitted to various Latter-day Saint leaders, including John Taylor and Joseph F. Smith, throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[70] In the most interesting of these requests, James asked to be “sealed” to Walker Lewis, the black Mormon elder who had lived in Lowell, Massachusetts, during the 1840s. According to James, “Brother Lewis wished me to be sealed to Him.”[71] These requests were rejected by Church authorities.[72]

As for Elijah Abel, even though he failed to secure his long-sought temple ordinances, he continued to be accepted as a member of the Third Quorum of Seventies as late as 1883.[73] In fact, during that same year Abel, then an elderly man in his early seventies, was appointed to serve a mission for the Church. He was set apart by Apostle Joseph F. Smith and sent to Ohio and Canada.[74] Abel’s missionary activities, however, were cut short by ill health, and he returned to Utah in early December 1884. Two weeks later he died of “old age and debility.”[75] His motives for going on a mission at such an advanced age is a mystery, especially at a time when his status as well as that of blacks in general had deteriorated. Perhaps he was motivated by a desire to demonstrate his “full faith in the Gospel” and thereby obtain long-sought temple endowments and sealings before his death.

The story of Elijah Abel and his activity in the Church is significant for several reasons. First, Abel’s changing status was a microcosm of what happened to all Mormon blacks during the nineteenth century. Up until the 1840s, Mormon blacks were accepted in full Mormon fellowship including the right to receive the Priesthood. However, by 1849 this was no longer the case; Mormon black priesthood denial was recognized as a churchwide practice. Even though Abel “got in under the wire” in receiving the priesthood, he and all other black Mormons were unable to participate in temple ordinances considered essential for full Mormon salvation.

Abel was significant for a second reason. Despite the parallels between Abel and other black Mormons, he was unique because of his status as one of Mormonism’s few known black priesthood holders. Because of his unusual status, Abel was the only known black Mormon to fulfill not one but three missions for the Church: full time missions in the 1830s and 1880s and a local mission in 1843. In addition, at least two of Abel’s descendants were apparently allowed to hold offices in the priesthood despite their black ancestry.[76] The unique status of Abel and his descendants was further underscored by the fact that they apparently did not interact with other Great Basin blacks or really consider themselves a part of Utah’s small but growing black community during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Abels stood part from other well-known black Mormons, including Jane Manning James, Samuel Chambers and Edward Leggroan.[77] In fact, it has been suggested that by the early twentieth century Abel’s descendants had managed to “cross the color line” and “pass for white.”[78]

Despite these developments, Abel’s race remained an issue that Latter-day Saints had to deal with during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1879, while Elijah Abel was still alive, his status as a black priesthood holder figured prominently in the efforts of certain Latter-day Saints to trace the origins of priesthood denial back to Joseph Smith. One of the leaders of this movement, Zebedee Coltrin, conceded that “Brother Abel was ordained a seventy because he had labored in the [Nauvoo] temple.” But Coltrin maintained that when Joseph Smith learned of Abel’s black lineage “he was dropped from the quorum and another was put in his place.”[79] However, Apostle Joseph F. Smith felt that “Coltrin’s memory was incorrect as to Brother Abel being dropped from the quorum of Seventies to which he belonged” since Abel had in his possession two certificates attesting to his status as a Seventy; the first “given to him in 1841” and a “later one” issued in Salt Lake City.[80] Abel spoke up in his own defense, stating that he had been ordained a Seventy back in 1836 by none other than Zebedee Coltrin! In addition, Abel stated “that the Prophet Joseph told him he was entitled to the priesthood.”[81] John Taylor tried to reconcile the conflicting views of Abel, Apostle Smith, and Coltrin by suggesting that Abel had “been ordained before the word of the Lord was fully understood.” Abel’s ordination, therefore, was allowed to stand.[82] By 1908, Joseph F. Smith, then president of the Church, abandoned the position he had taken in 1879 that Elijah Abel’s priesthood authority had been recognized by the Mormon Prophet. According to Smith, even though Abel had been “ordained a seventy … in the days of the Prophet Joseph Smith . . . this ordination was declared null and void by the Prophet himself” when he became aware of Abel’s black lineage.[83] Smith’s later view of Abel’s relationship to Joseph Smith fit in with the widespread Mormon belief that it was Joseph Smith, not Brigham Young who had fostered the practice of black priest hood denial.[84] This “rewriting of the Mormon past” was also reflected in the way Elijah Abel was presented in Andrew Jenson’s Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (1920). According to Jenson, Abel was ordained to the priesthood because “an exception” was “made in his case with regard to the general rule of the Church” against black ordination.[85] By 1955 even this qualified view of Abel’s place as a Mormon priesthood holder was denounced by Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith. In response to a private inquiry, Smith rejected Jenson’s account of Abel, suggesting that there were two Elijah Abels in the early Church—one white and the other black. Jenson had confounded the “names and the work done by one man named Abel . . . with the name of the Negro who joined the Church in an early day.[86]

At about the same time Joseph Fielding Smith was trying to bury the ghost of Elijah Abel once and for all, other individuals brought Abel back into the limelight through their efforts to probe the origins of black priesthood denial and the changing role of blacks within the church.[87] By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the unique status of Abel figured prominently in studies on the Mormon-black issue written by Dennis L. Lythgoe, Stephen G. Taggert and Fawn M. Brodie.[88] However, it was Lester E. Bush’s seminal Dialogue article that really underscored the unusual position of Elijah Abel both during his lifetime and after his death and its relationship to the often contradictory twists and turns of Mormonism’s policy toward its black members.[89] It would be nice to believe that the publicity given the history of Elijah Abel and his unique Mormon ordeal had some effect in undermining the historical justification for black priesthood denial. Whatever the case, the bringing forth of the June 1978 revelation abandoning black priesthood denial has restored Mormon blacks to the position of equality that they occupied during the 1830s when Elijah Abel joined the Church.

The author wishes to express his deep appreciation for the suggestions and information provided by the following individuals: Lester E. Bush, Jr., Associate Editor of Dialogue; H. Michael Marquardt of Sandy, Utah; Noel Barton of the LDS Church Genealogical Society; and William G. Hartley of the LDS Church Historical Department. Without the assistance of these individuals this article would not have been possible. In addition, a summer Grant-in-Aid provided by Indiana University at Kokomo made it possible for me to examine certain crucial materials in the LDS Church Archives in Salt Lake City.

[1] The three included John E. Page, Orson Pratt and Heber C. Kimball. Lorenzo Snow, an apostle (1849) and later church president, was also a member of this “Traveling High Council.”

[2] “Minutes of a conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints held in Cincinnati, June 25, 1843.” Original in LDS Church Archives.

[3] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, vol. 3 (Salt Lake City, 1920), p. 577.

[4] According to “Joseph Smith’s Patriarchal Blessing Record,” 88, recorded by W. A. Cowdery, Original, LDS Church Archives, Abel was born in 1808. In other census and church records, the 1810 birth date is used. There is some confusion about in which Maryland county Abel was born. According to Abel’s patriarchal blessing, he was born in Frederick County, but the “Mill Creek Ward Record of Members,” no. 1913, p. 63, original LDS Church Archives, lists Abel’s birthplace as Hancock, Washington County, while the “LDS Missionary Record” books A & B, 6176, Pt. 1860-1906, p. 75 (1883), microfilm 025664, Original LDS Church Archives, lists Abel’s birthplace as Hancock County. Finally, Abel’s obituary in the Deseret News (Salt Lake City) December 26, 1884 lists his birthplace as simply Washington County.

[5] The exact date of Abel’s ordination as an Elder is not clear. Abel’s December 26, 1884 Deseret News obituary says that he “was ordained an Elder as appears by certificate dated March 3d, 1836.” It is possible that Abel had been ordained before this date since “certificates of ordination” were frequently issued after the date of original ordination.

[6] Latter Day Saints Messenger and Advocate (Kirtland, Ohio) June 1836.

[7] “Minutes of the Seventies Journal,” kept by Hazen Aldrich, December 20, 1836. Original in LDS Church Archives.

[8] “Joseph Smith’s Patriarchal Blessing Record,” 88, recorded by W. A. Cowdery. Original, LDS Church Archives. Copied from Lester E. Bush, “Compilation on the Negro in Mormonism,” 16-17 (copy of unpublished manuscript in possession of author).

[9] Eunice Kenney, “My Testimony of the Latter Day Work” (unpublished manuscript 1885?, LDS Church Archives).

[10] “Minutes of the Seventies Journal,” June 1, 1839.

[11] As indicated by articles in newspapers, not only in Ohio, but as far away as New York and Pennsylvania. See Ashtabula Journal (Ashtabula, Ohio), February 5, 1831, taken from Geauga Gazette [n.d.]; Albany Journal (Albany, New York), February 16, 1831, reprinted from Painesville Gazette [n.d.] and The Sun (Philadelphia) August 18, 1831, taken from the A.M. Intelligencer [n.p., n.d.].

[12] Naked Truth About Mormonism (Oakland, Calif.), January 1888, quotes a statement of Henry Carroll, March 18, 1885, on Black Pete’s background.

[13] Ashtabula Journal, February 5, 1831 and Albany Journal February 16, 1831.

[14] The Sun, August 18, 1831. Also see Ashtabula Journal February 5, 1831. Later recollections have Pete chasing “a ball that he said he saw flying in the air” or “revelations carried by a black angel.” See Times and Seasons (Nauvoo, Illinois), April 1, 1842 and Journal of Discourses, (Liverpool, England), 11, George A. Smith, November 15, 1865.

[15] Naked Truth About Mormonism, January 1888.

[16] Doctrine and Covenants, 43:3-6.

[17] This according to a later recollection in the Times and Seasons, April 1, 1842.

[18] Parley P. Pratt, Late Persecutions of the Church of Latter-day Saints (New York, 1840), 28.

[19] As outlined in “A Declaration of Belief regarding Governments and Laws in General” approved by a general assembly of the Church held on August 17, 1835 which stated in part, “we do not believe it right to interfere with bond-servants .. . to meddle with or influence them in the least to cause them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life . . . such interference we believe to be unlawful and unjust, and dangerous to the peace of every government allowing human beings to be held in servitude.” This declaration was included as part of the Doctrine and Covenants (ultimately section 134.12) which was canonized in 1835.

[20] For one view outlining the development of Mormon antiabolitionist-antislavery attitudes during the 1830’s see Lester E. Bush, “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview, ” Dialogue, VIII (Spring 1973), 12-15. Also see: Warren A. Jennings, “Factors in the Destruction of the Mormon Press in Missouri, 1833,” Utah Historical Quarterly 15 (Winter 1967); Dennis L. Lythgoe, “Negro Slavery and Mormon Doctrine, ” Western Humanities Review 21 (Autumn 1967); and Stephen L. Taggart, Mormonism’s Negro Policy: Social and Historical Origins (Salt Lake City, Utah, 1970).

[21] See “Elijah Abel bapt for John F. Lancaster a friend,” as contained in Nauvoo Temple Records Book A100, original LDS Church Archives. Also see two other entries in this same record: “Delila Abel bapt in the instance of Elisha [sic] Abel. Rel son. Bapt 1840, Book A page 1” and “Delila Abel Bapt. in the instance of Elijah Abel 1841, Rel. Dau. Book A page 5. ”

[22] See Elijah Abel Papers, LDS Church Archives, for a description of this pamphlet which was printed according to an “Agreement, ” February 20, 1840, between E. Robinson and D. C. Smith—the Nauvoo town printers—and “Elijah Abel, Levi Jackson, Samuel Rolf, Alexander Badlam, Wm. Cahoon, W m . Smith and Elijah Newman. ” Robinson and Smith agreed “To Print for Abel, Jackson & Co., small pamphlet of 200 copies ‘Book of Prices of Work adopted by the House Carpenters of the Town of Nauvoo ‘ to be paid upon in labor or putting up a building when called upon. ” The sum agreed upon was $58.1 have not had the opportunity to look at the original but according to this reference the “original is in the possession of Mrs. Alfred M. Henson, St. George.”

[23] As recorded in “Minutes of First Council of Seventy, 1859-1863,” p. 494, March 5, 1879, LDS Church Archives.

[24] As noted by W. Wyl, Mormon Portraits (Salt Lake City, 1886), 51-52.

[25] Kate B. Carter, The Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City, 1965), 15; Jenson, Latter-day Saints Biographical Encyclopedia, 577. It is somewhat unclear what Carter meant by “living in the home” of Joseph Smith. It seems unlikely that Abel resided with the Smith family itself. Probably Abel lived in the Nauvoo House, a hotel guest-house run by the Smith family. In addition, Isaac Lewis Manning and his sister Jane Manning James were described as “servants” of Joseph Smith who both “lived for many years in the household of Joseph Smith.” See Carter, 9-13.

[26] Joseph Smith, Jr., History of the Church, (Salt Lake City, 1908). IV, June 6, 1841.

[27] As noted in the Cincinnati City Directories for 1842, compiled by Charles Cist (GS 194001) and for 1849-50 (GS 194002).

[28] As indicated by 1850 U.S. Census, 10th Ward, Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio, August 26, 1850 and 1860 U.S. Census, 13th Ward, Salt Lake City.

[29] Smith, History of the Church (Salt Lake City, 1902-1912) IV, January 2, 1843.

[30] “Minutes of a special Conference of the Cincinnati [sic] branch of the Church . . . held at Elder Pugh’s on the 1st day of June, 1845” as noted by Times and Seasons, June 1, 1845.

[31] William L. Appleby to Brigham Young, June 2,1847; also noted in William L. Appleby, “Journal,” May 19,1847, William L. Appleby papers in LDS Church Archives. There is, however, some confusion over who actually ordained Lewis. According to the recollections of Jane Elizabeth James, “Parley P. Pratt ordained Him an Elder.” See Jane E. James to Joseph F. Smith, February 7, 1890, as reprinted in Henry J. Wolfinger, “A Test of Faith: Jane Elizabeth James and the Origins of the Utah Black Community,” p. 149. The Wolfinger article is contained in Clark Knowlton, Editor, Social Accommodation in Utah (American West Center Occasional Papers, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1975). Also through an error committed by the compilers of the “Journal History,” MS in LDS Church Archives, the impression that Walker Lewis was a member of the Mormon branch at Batavia, New York was created. See “Journal History,” June 2, 1847. Such a false impression was obtained because Appleby’s letter describing Walker Lewis was mailed to Brigham Young from Batavia, New York. However, the contents of both this letter and Appleby’s “Journal” show Lewis to be a resident of, and member of the church at Lowell, Massachusetts.

[32] See Wilford Woodruff to Brigham Young, November 16,1844. Woodruff in his “Journal” during late 1844 and early 1845 made note of his numerous visits to Lowell and the areas around Lowell. Woodruff Papers, LDS Church Archives. Both Apostles Brigham Young and Ezra Taft Benson visited these same areas during 1844-45 and reported nothing unusual in the ethnic or racial qualities of Mormon priesthood holders.

[33] Woodruff to Young, November 16, 1844. According to Ezra Taft Benson to Brigham Young, January 22, 1845, Benson Papers, LDS Church Archives, the particular difficulties in the Lowell Branch came about as a result of church finances and the collection of funds.

[34] William L. Appleby to Brigham Young, June 2,1847; also noted in William L. Appleby, “Journal,” May 19, 1847, William L. Appleby Papers, LDS Church Archives. When Young finally had a chance to respond to Appleby’s inquiry following his return from the Great Basin to Winter Quarters in the fall of 1847, Appleby was present in person at Winter Quarters. Therefore, Young and/or other church leaders were able to respond to any questions that Appleby had on this matter. As for Walker Lewis, little is known about his activities after 1847. However, by October 4,1851, Lewis had journeyed to the Great Basin where he received a Patriarchal Blessing at the hands of John Smith. It is interesting to note that Lewis was assigned the lineage of Cainan. “Historian’s Office Patriarchal Blessings,” vol. 11, p. 326 as noted in Patriarchal Blessing Indices,” CR 5001 #64, LDS Church Archives. Lewis’ assigned lineage stood in sharp contrast to the “orphan” status assigned Elijah Abel some fifteen years earlier. But the lineage of “Cainaan” had been assigned to Mormon blacks as early as 1843. See references to patriarchal Blessings given by Hyrum Smith to Jane Manning and Anthony Stebbins as noted by “Patriarchal Blessing Index,” CR 5001 #64.

[35] “Manuscript History of the Church,” February 13, 1849, original, LDS Church Archives.

[36] McCary’s name was spelled a number of different ways: “McGarry,” “McCairey,” “McCarry,” “McCarey” as well as “McCary.” In one source he was referred to as “Wm. Chubby,” Juanita Brooks ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout (Salt Lake City, 1966), entry for March 8, 1849. In The True Latter Day Saints Herald (Cincinnati, Ohio), March 1861, he was referred to as “Mr. Williams the imposter.” For uniformity and simplicity of spelling I will refer to him as William McCary.

[37] Voree Herald, October 1846. According to the True Latter Day Saints Herald, March 1861, the agreement between Hyde and McCary was made in Nauvoo, Illinois where Hyde “married” McCary “to a white sister.”

[38] Cincinnati Commercial, October 27, 1846.

[39] Ibid. As indicated by a warning in the Commercial cautioning the citizens of this city to “Lookout for more sensuality in open daylight, in your families, and almost before your eyes, all under the cloak of sanctity.”

[40] Ibid, November 17, 1846.

[41] Zion’s Revelle (Voree, Wisconsin), February 25, 1847. Despite the short-lived nature of McCary’s Cincinnati activities they were noted by newspapers as far away as Illinois and Missouri. See Nauvoo New Citizen, December 23, 1846 and The Gazette (St. Joseph, Missouri), December 11, 1846.

[42] Juanita Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844-1861 (Salt Lake City, 1965), Vol. II, p. 244; John D. Lee, “Journal,” February 27, 1847, John D. Lee Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[43] John D. Lee, “Journal,” February 27, 1847. Young possibly had one or more of the following uses for McCary’s talents: (1) to dupe or mislead his Mormon rivals (2) to be an interpreter among the Indians as the Saints traveled west (3) to entertain the Saints on their westward trek with his talents as a mimic and ventriloquist.

[44] “Manuscript History of the Church,” LDS Church Archives, March 26, 1847. According to other accounts this “coolored man [sic] . . . showed his body to the company to see if he had a rib gone” and demonstrated his talents as a ventriloquist by passing himself off as an ancient Apostle Thomas— throwing his voice and claiming that “God spoke unto him and called him Thomas.” See Wilford Woodruff, “Journal,” March 26, 1847, Wilford Woodruff Papers, LDS Church Historical Department; The True Latter Day Saints Herald, March 1861. A brief mention of the confrontation between McCary and church leaders is also contained in Willard Richards, “Journal,” March 26, 1847, Willard Richards Papers, LDS Church Archives.

[45] Lorenzo Brown, “Journal,” April 27, 1847, Lorenzo Brown Papers, LDS Church archives; John D. Lee, “Journal,” April 25, 1847, Lee Papers.

[46] According to one account McCary joined the dissident Mormon Apostle Lyman Wight, then on his way to Texas. See John D. Lee, “Journal,” May 7, 1847 and the Latter-day Saints Millennial Star, January 1, 1849, which notes the interaction between Wight and the “Pagan Prophet.” Other accounts, however, suggest that McCary joined Charles B. Thompson, the leader of a minor Mormon schismatic sect based initially in Missouri and later in Iowa. In this regard see my “Forgotten Mormon Perspectives: Slavery, Race, and the Black Man as Issues Among Non-Utah Latter-day Saints, 1844- 75,” Michigan History, LXI, Winter 1977, 357-70. Finally, it has been suggested that McCary traveled “South to his own tribe.” See Lorenzo Brown, “Journal,” April 27, 1847, Brown Papers.

[47] Ibid., Nelson W. Whipple, “Journal,” October 14, 1847, Nelson W. Whipple Papers, LDS Church Archives; Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, entry for April 25, 1847.

[48] Zion’s Revelle, July 29, 1847.

[49] Nelson W. Whipple, “Journal,” October 14, 1847.

[50] These are my own compilations as derived from a number of sources including: Kate B. Carter, The Negro Pioneer; Henry J. Wolfinger, “A Test of Faith,” and Jack Beller, “Negro Slaves in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 2, 1929, 123-26. It is worth noting that the total number of blacks within Utah as compiled from these sources is considerably greater than the official U.S. census totals of 24 black slaves and 26 free blacks as reported for 1850. See U.S. Bureau of the Census, The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850 (Washington, D.C., 1853), p. 993.

[51] For two discussions of the forces leading to the enactment of these measures see Lester E. Bush, Jr., “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine,” 22-29 and Dennis L. Lythgoe, “Negro Slavery in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 39, 1971, 40-54.

[52] Newell G. Bringhurst, “A n Ambiguous Decision: The Implementation of Mormon Priesthood Denial for the Black Man—A Reexamination, ” Utah Historical Quarterly, 46, 1978, 45-64.

[53] Lester E. Bush, Jr., “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine, ” 22-29.

[54] Council Meeting Minutes, January 2, 1902, George A. Smith Papers, University of Utah Library; Council Meeting Minutes, August 12, 1908, Adam S. Bennion Papers, Brigham Young University Library.

[55] “Salt Lake Temple Time Book, ” December 1853, June and July 1854, originals in LDS Church Archives.

[56] “Mill Creek Ward Record of Members ” #1913 , pp. 63, 69. Original in LDS Church Archives.

[57] First Quorum of Seventies Minute Book, June 6, 1877, original in LDS Church Archives.

[58] This according to U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1860 Census, Utah, Salt Lake City, 13th Ward , #80S313, and 1870 Census, Weber County, Ogden, July 16, 1870, p. 44.

[59] This according to Salt Lake City Directory for 1869 and 1874, p. 14.

[60] Valley Tan, (Salt Lake City), April 26, 1859; Deseret News, April 27, 1859.

[61] Mrs. Annie Hermine Chardon Shaw, Federal Writer’s Project, pp. 1 & 5, Manuscript File, Utah State Historical Society.

[62] Deseret News, November 30, 1855; February 5, 1862.

[63] Ibid., July 27, 1864.

[64] “Ogden City Cemetery Records,” GS#979228/01 Vol. 220, pt. 1, give Maroni’s date of death as October 20, 1871.

[65] Deseret News, November 28, 1877, and “Salt Lake City Death Records, ” 1848-1884, #8099 , p. 203.

[66] Council Meeting Minutes, January 2, 1902, Adam S. Bennion Papers.

[67] For an excellent description of Jane E. Manning James’ life and activities see Henry J. Wolfinger ” A Test of Faith: Jane Elizabeth James and the Origins of the Utah Black Community, ” 126-147. Also see her autobiographical “Life Sketch of Jane Elizabeth Manning James, ” original in the Wilford Woodruff Papers. A copy of this “Life Sketch” has been included with Wolfinger’s essay, pp. 151-56.

[68] Wolfinger, 129-30.

[69] Ibid., 130-34.

[70] See “Documents Relating to Jane E. James” as contained in Henry J. Wolfinger, “A Test of Faith,” 150-151.

[71] See letter from Jane E. James to Joseph F. Smith, February 7, 1890 as reprinted in Wolfinger, “A Test of Faith,” 149.

[72] Church officials allowed Jane James to “be adopted into the family of Joseph Smith as a servant” through a “special” temple ceremony prepared for that purpose. See minutes of a Meeting of the Council of the Twelve Apostles, January 2, 1902, George A. Smith Papers.

[73] Third Quorum of Seventy, Minutes, 1883-1907, December 10, 1883, original in LDS Church Archives.

[74] Missionary Records, 6175, Part 1, 1860-1906, p. 75, 1883, original in LDS Church Archives.

[75] Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, vol. Ill, p. 557; Deseret News, December 26, 1884.

[76] This according to the findings of Jerald and Sandra Tanner, Mormons and Negroes (Salt Lake City, Utah, 1970), pp. 12, 16, which contains documentary evidence indicating that Enoch Abel, a son of Elijah Abel, was ordained an Elder on November 10, 1900, and that a grandson Elijah Abel was ordained a priest on July 5, 1934, and an Elder on September 29, 1935. The Tanners also suggested that Elijah Abel’s other surviving son, also named Elijah, may have been ordained to the priesthood.

[77] This is my own tentative conclusion based on an examination of various secondary works which describe the interaction and, indeed, intermarriage between members of Utah’s black community. See: Wolfinger, “A Test of Faith,” Kate B. Carter, The Negro Pioneer, and William G. Hartley, “Samuel D. Chambers,” The New Era, June 1974, 47-50.

[78] According to Jerald and Sandra Tanner, Mormons and Negroes, 18.

[79] L. John Nuttal, “Journal,” May 30, 1879, L. John Nuttal Papers, Brigham Young University Library. Coltrin also recalled that:

In the washing and Annointing of Bro Abel at Kirtland I annointed him and while I had my hands upon his head, I never had such unpleasant feelings in my life;—and I said I never would again Anoint another person who had Negro blood in him. unless I was commanded by the Prophet to do so [sic].

[80] Council Meeting, June 4, 1879, Adam S. Bennion Papers.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Minutes of a Council Meeting, August 26, 1908, Adam S. Bennion Papers.

[84] This important development is described in Bush, “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine,” 31-34.

[85] Vol. III, 577.

[86] Joseph Fielding Smith to Mrs. Floren S. Preece, January 18, 1955, S. George Ellsworth Papers, Utah State University, Logan.

[87] The first to do this was L. H. Kirkpatrick, “The Negro and the LDS Church,” Pen, 1954, 12-13, 29.

[88] Lythgoe, “Negro Slavery and Mormon Doctrine,” Taggart, Mormonism ‘s Negro Policy and Brodie, Can We Manipulate the Past? (First Annual American West Lecture, Salt Lake City, 1970).

[89] Bush, Op Cit 16-17, 31-34.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue