Articles/Essays – Volume 26, No. 3

B.H. Roberts’s Autobiography

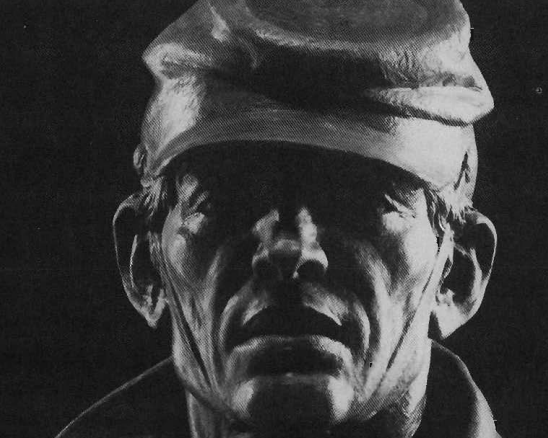

Less than one year before his death in 1933 at the age of seventy-six, Brigham H. Roberts began the bittersweet task of composing his autobiography (which was finally published nearly sixty years later by Signature Books). Known variously as “biographical notes” and “Life Story,” Roberts’s memoirs span the breadth of his life from the late 1850s as a neglected child in Dickensian England to post-World War I Utah as a respected, outspoken official of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They emphasize his adventures in pioneer Utah, his missions for the church, his career in partisan politics (including his opposition to women’s suffrage and to prohibition), his bid for the U.S. House of Representatives (from which he was barred for polygamy), and his activities as one of seven presidents of the First Council of the Seventy.

Only briefly did Roberts broach his marriages and family life; the historical and theological writings for which he had become known such as his Comprehensive History of the Church; or the last fifteen or so years of his life. He did not mention his appointment as a chaplain in France during World War I; his controversial study of the origin of the Book of Mormon; his unpublished theological magnum opus, “The Truth, The Way, The Life”; his treatises on Joseph Smith: Prophet, Teacher, The Mormon Doctrine of Deity, Defense of the Faith and the Saints, or Succession in the Presidency; or his disagreements with ecclesiastical colleagues over politics and church doc trine. As he approached more contemporary events perhaps he was unwilling to be as revealing as he had been in recounting earlier experiences; or perhaps the job of dictating his life story was simply too much of a strain for a man already suffering the debilitating effects of diabetes, depression, and old age; or perhaps he simply was reluctant to open old wounds.

Of his autobiographical notes, Roberts once disingenuously commented, “I do not think much of them. The conviction grows upon me that they ought not to be published. First, because my life is not of sufficient importance for a biography; second that it could not be fully told without arraigning others, and if told it must be fully and of course truthfully told; if that were done all Israel [the LDS church] could be greatly shocked. Theonly thing that would induce me to publish it would be to prevent someone else half and weakly doing it.” Of course, had Roberts lived longer there is little doubt that he would have seen to the completion of his “notes.” More than most, Roberts appreciated the lasting historical, social, literary, and political value of publication.

Although not completely reliable in every detail, nor as definitive and as thorough as might be hoped for, Roberts’s autobiography reveals a man of complexity and contradiction. For example, he insisted that he loved his mother deeply, yet it is apparent that he was devastated as a child when she abandoned him and his sister to abusive strangers while she emigrated with two of her other children to America. Her subsequent less-than-enthusiastic greeting at their reunion in Salt Lake City only underscored her apparent ambivalence. Roberts’s later relationships with women, especially his three wives and fifteen children, were probably colored by the conflicting emotions he felt toward his mother.

In addition, although Roberts pointed out that Mormon leaders hoped to double their political clout by granting women’s suffrage, he nonetheless was much slower than his contemporaries to be converted to equal rights for women. It is difficult to imagine that the same person who would later argue against prohibition—saying that nothing is “so dear to me as the liberty of the individual”—would not be similarly supportive of women’s suffrage. But such are the contradictions and inconsistencies that spot Roberts’s life.

While he chronicled in his autobiography a few incidents in his life after the mid-1920s, such as his concern over the status of the Seventy, Roberts failed to mention the deaths of two of his wives and his arguments with church officials. His first wife, Sarah Louisa Smith, twenty-three years old when they married in 1878, gave birth to seven children before passing away in 1923. She was followed less than three years later by Roberts’s third wife, Margaret Curtis (Shipp). Seven years Roberts’s senior, she married Roberts in 1890 and died at the age of sixty-nine in 1926. Celia Dibble, Roberts’s second wife, was twenty years old at the time of her marriage in 1884. She bore eight children and outlived her husband by two-and-one half years, passing away in 1936. In his autobiography, Roberts noted in passing only his marriages to Sarah and Celia, and his children by Celia.

In late 1921, two years after returning home from France where he served as a chaplain during World War I, Roberts was asked to respond to a series of questions regarding the historicity of the Book of Mormon. In response, he produced two manuscripts, “Book of Mormon Difficulties” and “A Book of Mormon Study,” detailing problems which could be used to question the validity of the church’s founding scripture as an ancient document.

The first manuscript was presented to the Council of Twelve Apostles for their consideration in late January the next year. Roberts had noted linguistic problems in the Book of Mormon, wondering, for example, how so many languages could have evolved from one language in only one thousand years. Also, he was concerned about the lack of archeological evidence for Book of Mormon mention of domestic animals, iron, steel, wheat, barley, and wheeled vehicles. The second manuscript, which he apparently completed in 1923 and did not present to church authorities, discussed possible Book of Mormon parallels with an early 1820s book on native Americans and ancient Israelites, entitled View of the Hebrews, and internal inconsistencies in the Book of Mormon.

In a cover letter to church president Heber J. Grant, which accompanied the first manuscript, Roberts explained his motives for undertaking such a project. “I am thoroughly convinced,” he wrote, “of the necessity of all the brethren herein addressed becoming familiar with these Book of Mormon problems, and finding the answer for them, as it is a matter that will concern the faith of the youth of the Church now as also in the future, as well as such casual inquiries that may come to us from the outside world.” Believing that “our faith is not only unshaken but unshakable,” Roberts felt it was desirable to face these challenges directly. ‘Maintenance of the truth of the Book of Mormon is absolutely essential to the integrity of the whole Mormon movement,” he wrote in another letter to Grant, “for it is inconceivable that the Book of Mormon should be untrue in its origin and character and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to be a true church.”

Roberts’s controversial studies were interrupted when he was called in early 1922 to serve as president of the church’s eastern states mission, headquartered in New York City. Although never printed during his life, his two manuscripts were first made available in 1980 by Modern Microfilm Company of Salt Lake City and then published by the University of Illinois Press in 1985 as Studies of the Book of Mormon, edited and introduced by Brigham D. Madsen, with a biographical essay by Sterling M. McMurrin.

After five years in New York City, Roberts was released in 1927 and began work on a new theological project he hoped would be his “master work.” Late the next year, he submitted to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles a bulky, 747-page manuscript entitled, “The Truth, The Way, The Life: An Elementary Treatise on Theology.” Designed as a lesson manual for Melchizedek priesthood quorums throughout the church, Roberts’s ambitious work contained, he explained, “a full harvest of all that I have thought, and felt and written through the nearly fifty years of my ministry, that is on the theme of the title.” Within three weeks, the twelve apostles appointed a reading committee, composed of Elders George Albert Smith, David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, Stephen L Richards, and Melvin J. Ballard, “to examine the manuscript of Brother Roberts’ work, and make a recommendation as to its suitability for the study of the High Priesthood.”

One year later, committee chair George Albert Smith reported his group’s findings to the rest of the twelve. The committee found that by and large the work was a “very worthy” treatment of church beliefs. They were, however, uncomfortable with “some objectionable doctrines advanced which are of a speculative nature and appear to be out of harmony with the revelations of the Lord and the fundamental teachings of the Church.”

The committee voiced special concern with the following points: the existence of races of humans before Adam; the suggestion that Adam was a translated being subject to death who did not bring death to his posterity as a result of the Fall; Adam’s placement on the earth before other life belonging to our present dispensation; the complete destruction of all life prior to Adam’s advent; and God’s continuing acquisition of knowledge. Other problems existed, and of the fifty-four chapters, twenty were found to contain questionable teachings.

The twelve formally reported to President Grant in mid-May 1930, one month after Roberts lost part of his right foot to diabetes, that “[we] do not regard said work in its present form as a suitable study for the Priesthood quorums of the Church.” Throughout the next months, Roberts was told that his treatise would be published if he modified or changed altogether his more controversial concepts in keeping with the committee’s suggestions. Roberts refused, adamant that his work appear in its present form or not at all. Consequently, though abbreviated excerpts have since appeared in articles and books, Roberts’s magnum opus, “The Truth, The Way, The Life,” has gone unpublished for more than sixty years. (In fact, only recently has work begun under the editorship of Stan Larson, a curator at the University of Utah library, on preparing the manuscript for publication.)

Joseph Fielding Smith, who had served on the committee of apostles to review Roberts’s manuscript, subsequently criticized Roberts’s views in public. Always ready to defend his position, the feisty Roberts immediately registered an official complaint with the First Presidency. “If Elder Smith is merely putting forth his own opinions I call in question his competency to utter such dogmatism either as a scholar or as an Apostle,” he wrote to President Grant. But Grant recorded in his diary, “I think no good can be accomplished by dealing in mysteries, and that is what I feel in my heart of hearts these brethren are both doing.” Roberts hoped that a formal airing of both sides would help pave the way for the publication of his own beliefs.

Hearings before the twelve at which Roberts and Smith presented arguments in support of their views—especially on the existence of pre-Adamic races—resulted in a stalemate, and the controversy was referred back to the First Presidency. Lacking an authoritative statement on the subject, Grant and counselors ruled that the topic was not to be raised again by church officials, though one general authority, James E. Talmage, eventually countered Smith’s denunciations in a 1931 address in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. Talmage argued for the existence of death before the fall of Adam and for a geologically old earth. His speech was later published and widely distributed.

The final three years of Roberts’s life were marked by the publication of his six-volume Comprehensive History of the Church in commemoration of the centennial of the church’s founding, completion of routine church assignments and administrative matters, public sermons (Roberts was a favorite speaker at funerals), attendance at the World Fellowship of Faiths in Chicago, and the preparation and dictation of his autobiography. Despite bouts of severe depression, including migraine headaches and spells of dizziness, Roberts also contemplated several new projects, including the establishment of a theological school, but poor health prevented him from accomplishing these goals.

Shortly before noon on Tuesday, 27 September 1933, Roberts passed away in Salt Lake City. He was buried four days later on 1 October. His last words, reportedly spoken to an attending nurse, were: “You had better give me my coat. I am not going to stay here in bed. I have stayed long enough.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue