Articles/Essays – Volume 41, No. 1

Can Deconstruction Save the Day? “Faithful Scholarship” and the Uses of Postmodernism

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Writing in the mid-1990s, Mormon-watcher Massimo Introvigne made a counterintuitive observation about debates over Book of Mormon historicity among Mormon intellectuals, as compared to analogous debates between Protestant fundamentalists and liberals. Fundamentalists, despite their reputation for being anti-scientific, were “deeply committed to Enlightenment concepts of ‘objective knowledge,’ and ‘truth,’” confident that an impartial view of the data would confirm the historical authenticity of the Bible. Protestant liberals, in contrast, deployed a “post-modern, anti-Enlightenment epistemology” to undermine absolutist readings of the Bible. The opposite dynamic, however, prevailed in the Book of Mormon debates. Liberals publishing with Signature Books—such as Edward Ashment and David P. Wright—were “staunch defenders of the Enlightenment,” with its ideals of disinterested reason and the unfettered search for truth, while conservatives publishing with the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) held “the late modernist and post-mod ernist position that knowledge is by no means objective, and that ‘true,’ universally valid, historical conclusions could never be reached.”

For observers who equate “postmodern” with relativism or use “deconstruction” as academese for “destruction” (as in “the deconstruction of traditional values”), Introvigne’s analysis must be puzzling. Why would defenders of a religious orthodoxy that claims access to absolute truth and an exclusive dispensation of divine authority align themselves with postmodern epistemologies that destabilize claims to truth and authority? Little wonder that one liberal critic, Brent Lee Metcalfe, has branded the alignment contradictory.

Whether the use of postmodern appeals by orthodox LDS scholars is philosophically consistent or contradictory is not a question I will address in this essay. Partly this is because I lack the training to engage that question with philosophical rigor; partly it is because I see more interesting, and useful, questions to ask. My project here is to provide historical perspective on the use of postmodern appeals by “faithful scholars” over the last twenty-five years, inquiring into these appeals’ rhetorical efficacy and political uses. By invoking postmodern authorities and lines of reasoning, what new discursive and institutional spaces have LDS scholars carved out for themselves? How have orthodox scholars used postmodern appeals to intimidate rivals? And how effective are those appeals likely to be at persuading non-Mormon academics to take seriously the work of faithful scholars at a time when Mormon studies is starting to be institutionalized in the academic mainstream?

While I reject “contradiction” as a term of analysis for my purposes, I do want to underscore the unresolved ambiguities involved when postmodern rhetorics are pressed into the service of LDS orthodoxy or a conservative brand of cultural politics. We will see that LDS scholars hold conflicting or ambivalent attitudes toward postmodernism. At the same time, ambivalence among postmodern scholars outside Mormonism constrains faithful scholars’ ability to invoke postmodern grounds to legitimize scholarship grounded in orthodox LDS presuppositions. In certain respects, postmodernism has been a godsend for LDS scholars wanting to challenge skepticism about their faith’s supernatural claims, but it is not clear how efficacious a savior postmodernism will prove in the long run.

Key Terms

Faithful Scholarship

“Faithful scholarship” is a preferred self-identifying label for what I have elsewhere called “orthodox scholarship,” meaning scholarship predicated on the literal, historical reality of LDS supernatural claims (such as the antiquity of the Book of Mormon), on the LDS Church’s exclusive claim to divine authority, and on the deference owed to Church leaders. Though Richard Bushman coined a precursor term, “faithful history,” in 1969, the terms “faithful scholarship” and “faithful scholars” came into vogue in LDS parlance beginning in the late 1980s, after Neal A. Maxwell expressed his pleasure that “faithful Latter-day Saint scholars” were helping to demonstrate the divinity of the scriptures. Cognate terms include “believing history” and “the perspective of faith.”

“Faithful scholarship” does not name a clearly defined school or methodology, but it does point to an orientation or approach toward scholarship that, as we will see, emerged by distinguishing itself from other approaches within the LDS intellectual milieu, such as the new Mormon history. Faithful scholarship has become normative for institutions affiliated with the Church, including BYU Studies, FARMS, the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Latter-day Saint History (prior to its dissolution in 2005), and the Church and Family History Department of the LDS Church. A number of faculty in BYU Religious Education do faithful scholarship as well, though Religious Education is officially committed to something it calls “gospel scholarship,” which is more overtly faith-promoting and less academically rigorous than “faithful scholarship.” Sunstone and Dialogue occasionally publish works of faithful scholarship; but faithful scholars, given their commitments to orthodoxy, are likely to view Sunstone and Dialogue as unsafe forums in which to publish. The Mormon History Association remains open to scholarship reflecting a variety of orientations but has somehow managed to avoid the stigma attached to Dialogue and Sunstone.

Deciding who counts as a “faithful scholar” is tricky because that label doubles as a description of a particular scholarly orientation and also as a claim about a scholar’s good standing in the Church. Leonard J. Arrington and Eugene England would have insisted that they were faithful Church members, but neither exemplified the orientation I am calling faithful scholarship. Both were too wedded to objectivity as a scholarly ideal (rather than working from “the perspective of faith”) and too closely affiliated with Sunstone and Dialogue. For the most part, “faithful scholars” are those who affiliated during the 1990s or beyond with institutions that used rhetoric about faithful scholarship or working from the perspective of faith to define their missions. By this criterion, the label applies to John W. Welch, Louis Midgley, Daniel Peterson, Noel Reynolds, Grant Underwood, Ronald K. Esplin, Jill Mulvay Derr, Richard Lyman Bushman, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Robert L. Millet, among others. The label also applies to Terryl Givens. Other scholars have affinities with faithful scholarship but don’t quite fit into the “faithful scholar” category, perhaps because they keep some distance from the institutions of faithful scholarship, because they evince certain “liberal” tendencies, or perhaps because they’re simply not interested in working from an overtly LDS perspective. Such scholars include Philip Barlow, Kathleen Flake, and Armand L. Mauss. Scholars who clearly work outside the faithful scholarship category—because their work is too revisionist in tenor or their religious views too heterodox—include D. Michael Quinn, Klaus Hansen, Newell G. Bringhurst, Margaret Merrill Toscano, and Thomas W. Murphy, to name just a few. Mormon scholars outside faithful scholarship, it should be noted, are a highly diverse crowd; they can, in fact, be separated into additional categories, as I will do below.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism is notoriously difficult to define: The term is applied very widely, at times to the work of figures who do not claim the label for themselves. One explicator of postmodernism writes that “the term . . . hovers uncertainly in most current writings between—on the one hand—extremely complex and difficult philosophical senses, and—on the other—an extremely simplistic mediation as a nihilistic, cynical tendency in contemporary culture.” Routine academic usage falls somewhere in between; in that usage, “postmodernism” refers to a theoretical turn—or a set of related theoretical turns—that have transformed scholarly inquiry in many disciplines, beginning in the 1960s but making greatest headway in the 1980s and 1990s.

Postmodernism has been most influential in the arts and humanities, somewhat less so in the social sciences, and considerably less so in the natural sciences. Entirely new fields have emerged from the academy’s turn to ward the postmodern: cultural studies, gender studies, gay/lesbian studies, queer theory, postcolonial theory, and science studies, among others. Critics on the political right charge postmodernists with enforcing an orthodoxy of political correctness, a reaction to the prominence of left-wing identity politics in postmodern scholarship. However, contrary to the impression this charge may create, postmodernism is not a monolith or well-defined school of thought. Postmodernism encompasses, rather, a number of different philosophies or critical theories, and writers commonly accepted as postmodern may be in sharp conflict with one another. For the purposes of my analysis, however, I will hazard the following generalizations.

The “modern” in “postmodern” refers to the intellectual and social transformations that followed from the Enlightenment in eighteenth-century Europe. Those transformations included the rise of democracy and capitalism, European and American imperialism, scientific and technological advances, and the secularization of many social sectors (e.g., as a result of principles of church-state separation). Postmodernists are preoccupied with the totalitarian or destructive aspects of these developments. In the Enlightenment’s pursuit of progress and freedom, who has been excluded or oppressed? Deeply skeptical of grand theories or narratives that profess to account for all phenomena and experience, postmodern scholars shift the focus of attention to those who are rendered invisible or voiceless by accounts of reality that profess to be total or universal. For this reason, postmodern scholarship tends to focus on the voices, knowledges, and interests of those who were marginalized by the Enlightenment: women, racial minorities, sexual minorities, colonized peoples, the working classes, or people stigmatized as irrational or insane. This shift in focus from elites to the social periphery has led to the stereotype of postmodernists as people with a knee-jerk disdain for “dead white males.”

Especially relevant to understanding faithful scholars’ use of postmodernism is the postmodern rejection of professions of objectivity; postmodernists see such professions as characteristic of scholarship in intellectual streams descended from the Enlightenment. Based on sophisticated reflections in epistemology and linguistics, postmodern theorists maintain that human beings cannot apprehend reality as it is—or at least, we could never know if we have apprehended reality as it is—because our knowledge is inescapably mediated by language and culture. To borrow the language of Doctrine and Covenants 93:24, our knowledge of things as they are and were and are to come is confined to representations or interpretations of things as they are and were and are to come.

In this view, truth is not “out there” waiting to be discovered; what human beings take to be truth is something that we ourselves have constructed. Here postmodernism displays the influence of Friedrich Nietzsche’s perspectivist philosophy, according to which we can know things only from a specific perspective. Postmodern scholars are often self-conscious about viewing their subject from a particular social location or position (hence the terms “particularity” and “positionality”), not from the perspective of a universal “everyman” detached from the historical, cultural, economic, political, and linguistic contexts that shape our knowledge. Postmodernists squirm at statements that begin, “All rational people would agree that . . .” They recognize that human beings are never disinterested—that our approach to a subject is always shaped in advance by presuppositions, conceptual categories, or theories, and that there are always agendas at stake (our own or others’) in how we conduct scholarship and what representations we construct as a result.

While postmodernism is undeniably relativistic, it is many times more sophisticated than popular understandings of relativism as “Anything goes,” or “Everyone is right.” For one thing, a postmodern critic would question the concept of the self implicit in popular relativism, i.e., the assumption that we are autonomous individuals capable of making free choices about our beliefs and morals. Postmodernists would want to know how we came to believe that about ourselves: What is the history, or genealogy, of that understanding of the self? Postmodernists would call attention to the historical and cultural forces that produce—and by the same token, restrict—our perceptions of the philosophical or moral options available to us. They would be interested in identifying the social processes that construct the desires which guide our choices. Postmodernists would point out (contra popular versions of relativism) that not all philosophical or moral options are equal because, when we encounter them, they are already embedded in systems that lend some philosophies or moralities greater privilege or power than others. All this is to say that postmodernism is less interested in making pronouncements about what is true than in investigating the historical origins of our ideas about what is true and analyzing the political implications of those ideas. Whose interests are served, and who is disadvantaged, by particular systems of belief or morality? One common mode of postmodern scholarship is to problematize the categories on which dominant constructions of truth rely—for instance, by showing that these categories depend on neat dualisms that cannot, in fact, be neatly maintained, or by showing how ideas assumed to be timeless or obvious arose at specific historical moments to serve particular interests. These destabilizing strategies are often referred to as deconstruction.

It should be clear from this discussion that postmodernism is driven by ethical concerns (e.g., concern about the suffering or injustice experienced by marginalized people). At the same time, postmodernists are wary of ethical systems (or other systems of knowledge) that claim an absolute foundation. Instead, postmodernists see knowledge as resting uneasily on foundations that are provisional or cobbled together—and socially constructed, not originating in a transcendent source such as the will of God or an indubitable conception of the good. This philosophical outlook is known as antifoundationalism. As an extension of their antifoundationalism, postmodernists tend to be drawn toward pluralistic visions of a world in which diverse communities, truths, and moralities negotiate a constantly shifting shared existence.

Among the varieties of knowledge that the Enlightenment heritage has tended to classify as “irrational” is religion—at least the kind of unabashedly supernaturalist religion that Mormon orthodoxy represents. For that reason, religious conservatives from a number of traditions have, during the past couple of decades, adopted postmodern appeals against being marginalized in the name of universal rationality. Mormons in academia are among the religious conservatives making these moves. As I hope is apparent by now, there are some aspects of postmodernism to which LDS scholars could readily subscribe—concern for the marginalized, for instance. At the same time, there are other aspects—such as antifoundationalism—that are more difficult to reconcile with the absolute truth claims of Mormon orthodoxy. We now turn to examining the particular uses that faithful scholars have made of postmodernism and the ambiguities that surround their doing so.

Antipositivism and the New Mormon History

The history of postmodern appeals among orthodox Mormon scholars begins with the antipositivist critiques that BYU political science professors Louis Midgley and David Bohn led against the new Mormon history in the 1980s and early 1990s. Like “faithful scholarship” and “postmodernism,” “new Mormon history” is a problematic label. It has been imprecisely applied, and efforts to identify “new Mormon historians” have yielded different names. Nevertheless, the term was commonly used, by critics and defenders alike, to describe a discernible historiographical orientation that dominated the wave of professional Mormon histories written during the 1960s and 1970s. The most prominent representatives of this orientation were Leonard J. Arrington and Thomas G. Alexander— Arrington because of his influence as Church historian, Alexander because he undertook to publicly respond to the antipositivists’ criticisms.

The chief defining characteristic of the approach to Mormon history championed by Arrington and Alexander was that it aspired to be objective in the sense of transcending pro- versus anti-Mormon polemics. Arrington and Alexander described the new Mormon history as a “middle ground” between veneration and antagonism or between evangelism and secularism. The key to this via media was to maintain what one colleague of Arrington’s called a “restrained religious voice” and what another observer dubbed “sympathetic detachment.” The Story of the Latter-day Saints and The Mormon Experience, both produced by the Arrington led History Division in the Church’s historical department, exemplified this dispassionate approach.

After the new Mormon historians came under attack from the antipositivists, Arrington and Alexander denied that they had ever professed objectivity in the naive sense of believing themselves to be perfectly disinterested or purged of preconceptions. Arrington did, however, characterize the historian’s task as being “impartial and objective.” The new Mormon history aspired to a supposedly universal knowledge—“to understand as scholars of any faith or no faith would seek to understand.” The aspiration to objectivity and universality revealed the deep influence of the Enlightenment on the new Mormon history, although that influence was channeled by way of a Romantic humanism. In this Romantic discourse, religion was interiorized as individual “experience,” a subjectivizing move that allowed the new Mormon historians to sidestep questions about the objective reality of Mormon claims to revelation.

Another figure whose work was targeted by the antipositivist critique was non-Mormon scholar Jan Shipps, author of the first booklength study of Mormonism to use the methods of religious studies (rather than history). Shipps’s “history of religions” approach complemented the via media of the new Mormon history because, like Arrington, Alexander, and others, Shipps declined to evaluate questions about the truth of Mormon faith claims like the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. Instead she focused on “reconstructing the picture of early Mormonism as perceived from the inside.” Shipps described her approach as “bracketing” questions of ultimate truth. She derived the concept of bracketing from the phenomenology of religion, a tradition that emerged in Dutch theological faculties in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Similar to the new Mormon historians, phenomenologists of religion aspired to blaze a third way between the confessional affirmations of theology and what they saw as the reductive—that is, strictly secular—theories about religion that had developed in the fields of psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Phenomenologists believed that their approach was simultaneously objective and sympathetic toward the religions they studied and that it was therefore able to successfully capture the understandings of religious insiders. Although phenomenology of religion opposed more militantly secular forms of Enlightenment-descended scholarship (as represented, for instance, by Freud), phenomenology itself was grounded in Cartesian, and thus quintessentially Enlightenment, ideals of objectivity.

Midgley and Bohn launched their antipositivist critiques of the new Mormon history in the early 1980s together with Neal Kramer, then a doctoral student in English language and literature. Kramer and Bohn accused “the new Mormon historians and their supporters” of having bought into the “positivist ideology” that Kramer and Bohn alleged controlled the discipline of history. Among “new Mormon historians and their supporters,” Bohn named Leonard J. Arrington, Davis Bitton, Robert B. Flanders, Klaus Hansen, Lawrence Foster, and Jan Shipps. In calling these scholars positivists, Kramer and Bohn meant that their work excluded “non-scientific testimony of the role of God” in Mormon history, relying instead on “psychological, sociological, and economic explanations” that claimed to be objective and neutral. Kramer and Bohn rejected that claim, citing in their support a roll call of philosophers and theorists whose work either participated in or anticipated the postmodern turn: Ludwig Wittgenstein, Richard Rorty, Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida. “Precisely because theories are not neutral,” Bohn argued, “Mormon historians can legitimately take issue with secular explanation.”

Midgley was more strident, accusing the new Mormon historians of having committed an “act of treason” against the faith by attempting to be neutral about Joseph Smith’s prophetic claims. Because there is no such thing as objectivity in history, Midgley insisted, LDS historians ought therefore to unabashedly adopt the role of “defenders of the faith.”

Midgley and Bohn pressed their case through the late 1980s and into the 1990s, joined by other voices such as Daniel Peterson, who also lent Midgley the FARMS Review as a forum for his criticisms. After its publication in 1988, historian Peter Novick’s That Noble Dream became a favorite authority to support the antipositivists’ contention that the new Mormon historians’ aspirations to objectivity were futile and naive. To the list of postmodern authorities already cited, the antipositivists would eventually add Dominick LaCapra, Jean-François Lyotard, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Stanley Fish.

In opposing the new Mormon history’s ostensibly neutral approach, Midgley and Bohn extended a critique that had already been made by CES personnel and Apostle Boyd K. Packer, who found the new Mormon history too secular and inadequately faith-promoting. In his controversial 1981 address, “The Mantle Is Far, Far Greater Than the Intellect,” Packer rejected the quest to be “objective, impartial, and scholarly” in writing Church history on the grounds that Latter-day Saints were at war. The “posture of detachment” or “sympathetic neutrality” to which some LDS scholars aspired (Packer was almost certainly thinking of Arrington, specifically) risked “giving equal time to the adversary.”

At its core, the antipositivist complaint was identical to Packer’s: Mormon historians needed to stand on the side of the gospel, not on some fictitious objective middle ground. But Midgley, Bohn, and other antipositivists couched that complaint in much more sophisticated language than Packer. In doing so, they altered the terms of the historiographical debate. When Arrington’s History Division had come under fire during the 1970s from apostles Ezra Taft Benson, Mark E. Petersen, and Boyd K. Packer, media coverage of the controversy framed it in terms of simple anti-intellectualism: “Apostles vs. Historians.” That frame was obviously not applicable to a criticism voiced in the idiom of antifoundationalist philosophy.

The sophistication of the antipositivist critique caught the new Mormon historians off guard. Around the same time, the demise of Arrington’s History Division and the “Petersen inquisition” of 1983— when Mark E. Petersen instructed local Church leaders to interview more than a dozen LDS writers, including Thomas G. Alexander, Armand Mauss, Linda King Newell, David John Buerger, and Lester E. Bush— drove home that Mormon historians were vulnerable to losing their Church membership and, for BYU faculty, their jobs if Church leaders perceived their work as a threat. Probably for this reason, the new Mormon historians were reluctant at first to let the antipositivist controversy enter print. Finally, Alexander broke silence in 1986 with a Dialogue article in which he defended the new Mormon history from the charge of positivism by tracing its intellectual genealogy to a Romantic historical tradition that began with Goethe and Schleiermacher and extended—Alexander claimed—to Max Weber and Michel Foucault. If the mention of Foucault was Alexander’s attempt to invoke a postmodern authority, it was far from obvious what the new Mormon history had in common with Foucault’s sophisticated analyses of power and discourse.

Observers recognized that Alexander had not effectively answered the antipositivists’ objections on the question of objectivity. Alexander was unprepared to deploy antifoundationalism as the political scientists had done. Furthermore, he continued to place the new Mormon history in a middle ground between “traditionalists” and secularists, a position that was becoming indefensible in an increasingly restrictive Mormon intellectual climate. By the mid-1990s—after Church leaders had taken a number of steps to check heterodoxy among intellectuals, including the Statement on Symposia, the September Six excommunications, and the firing of BYU professors—defenders of Arrington’s universalist approach to historiography had fallen silent. The last word in the debate was left to Bohn’s philosophically dense and intimidating 1994 Sunstone essay, “The Larger Issue.” Several years later, a speaker at a Smith Institute symposium on historiography assured his audience that the “positivism” of new Mormon historians—among whom he named Thomas Alexander and Jan Shipps—had been “thoroughly discredited.”

It is doubtful that the postmodern authorities cited by the antipositivists would concur that, from their theories, it followed that Mormon historians ought to defend affirmations of supernatural interventions in history and exclusivist claims to divine authority. Postmodern theorists were useful to the antipositivists because they wielded academic authority against the Enlightenment ideals undergirding the new Mormon history (as well as more radically revisionist scholarship). But Midgley’s and Bohn’s defenses of LDS orthodoxy represented an antimodern rather than a postmodern position. Ultimately, the antipositivists’ agendas had little in common with those of the postmodern authorities whose words they appropriated; although postmodernists and antipositivists alike were critical of the Enlightenment, they had very different motives for being so.

Nevertheless, the antipositivist critiques were highly significant within the Mormon intellectual world because they opened up an important new line of argument for scholars who wanted to be both religiously orthodox and academically credible. In the 1970s, even Boyd K. Packer had conceded that orthodox claims would have to be toned down in a history written for a non-LDS audience. Midgley and Bohn, in contrast, had modeled a way of articulating a commitment to LDS orthodoxy that could make a bid for academic legitimacy. That possibility would be pursued from other angles during the 1990s and beyond.

Faithful Scholarship as Perspectivism

The antipositivist critiques were the forerunner to a diffuse postmodern sensibility among orthodox LDS scholars during the 1990s. This sensibility was not typically expressed in philosophically rigorous language like that with which Bohn had bowled over defenders of the new Mormon history. Instead, the postmodern turn among LDS scholars in the 1990s consisted of the widespread adoption of a rhetoric that asserted the legitimacy of scholarship reflecting an orthodox LDS “perspective.” This appeal for legitimacy relied on a broader turn toward perspectivism that had occurred in academia under the influence of postmodernism. As we will see, it is not evident that orthodox LDS scholars have embraced perspectivism as a philosophy or worldview. But perspectivist language has played important roles: as a potent instrument in contests to elevate “faithful scholarship” over rival orientations among LDS intellectuals and as the primary rhetorical resource for those who hope to win credibility for faithful scholarship within the academic mainstream.

When Neal A. Maxwell popularized the term “faithful scholars” in the late 1980s, he used it to indicate scholars’ commitment to the Church and its doctrines and their willingness to use their intellectual gifts to “protect our flanks” from detractors. It is not clear that Maxwell’s usage implied an appeal to perspectivism. The term “faithful scholarship” took on its perspectivist cast during the subsequent decade as leading centers for the production of Mormon scholarship at BYU incorporated commitments to the faithful-scholarship orientation into their mission statements. When FARMS founder John W. Welch became editor of BYU Studies in 1991, the journal’s mission statement was expanded to accentuate its commitment to LDS perspectivism, namely, to “publish articles that openly reflect a Latter-day Saint point of view.” Similarly, the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute, until it was disbanded in 2005, defined itself as “a center for the scholarly study of Mormon history from the perspective of faith.” Although its language was not explicitly perspectivist, FARMS, too, announced the particularity of its knowledge production when it explained that “work done in the name of FARMS rests on the conviction that the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and other ancient scripture. . . are authentic, historical texts.” This stance was far removed from Arrington’s attempt to understand as someone “of any faith or no faith” would understand—a universalizing project that FARMS’s Daniel Petersen had pronounced doomed to failure.

These three institutions—BYU Studies, the Smith Institute, and FARMS—were not the only sites for producing and disseminating scholarly knowledge about Mormonism; and the perspectivism these institutions employed in explaining their missions was by no means universal among LDS scholars working on Mormon topics. As we will see later, not even all of those who embraced a commitment to “faithful scholarship” understood that commitment in perspectivist terms. However, perspectivism gained greater influence within the LDS intellectual milieu over the course of the 1990s as “faithful scholarship” successfully marginalized all rival scholarly orientations to become normative for LDS scholarship under Church auspices. As a result of that process, BYU Studies, FARMS, and (to a lesser degree) the Smith Institute, together with the scholars associated with them, became advantageously positioned to develop and promote their perspectivist modes of scholarship.

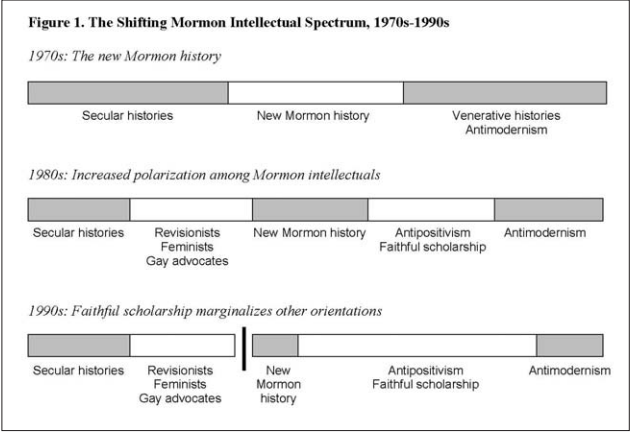

How did this happen? During the 1970s, the chief divide in Mormon intellectual politics had lain between the new Mormon history and the antimodernism represented by CES and leaders such as Packer. This was the conflict that the media had framed as “Apostles vs. Historians.” Arrington’s History Division had been the conflict’s epicenter. In the course of the 1980s, polarizing developments such as the antipositivist critiques, debates around the Hofmann forgeries, and an expanding body of revisionist, feminist, and gay-affirmative literature, had made it possible to map additional “camps” onto the Mormon intellectual spectrum. To the left of the new Mormon historians stood revisionists such as Edward Ashment, George D. Smith, Dan Vogel, Brent Metcalfe, and D. Michael Quinn, who went farther in challenging canonical accounts than new Mormon historians such as Leonard Arrington and Thomas Alexander had done. The revisionists’ work, together with the writings of feminists and gay advocates, created a heightened sense of threat for orthodox Latter-day Saints, as reflected in Boyd K. Packer’s famous 1993 warning against intellectuals, feminists, and gays.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1: The Shifting Mormon Intellectual Spectrum, 1970s-1990s, see PDF below, p. 14]

Meanwhile, occupying a space on the Mormon intellectual spectrum between the new Mormon history and the antimodernism of CES were the antipositivist arguments of Louis Midgley and David Bohn and the work being produced, especially at FARMS, by the cohort Neal A. Maxwell called “faithful Latter-day Saint scholars.” Maxwell directly encouraged the work of this cohort through quarterly meetings held, beginning in 1984, with fellow junior apostle and former BYU president Dallin H. Oaks, then-BYU president and future apostle Jeffrey R. Holland, and faculty members from Religious Education, the Smith Institute, and FARMS. Maxwell and Oaks urged LDS scholars to write effective responses to challenges posed by revisionists like George D. Smith or the awkward revelations of the historical documents being “discovered” by Mark Hofmann. Maxwell was particularly supportive of FARMS. Of these four “camps”—revisionists, new Mormon historians, faithful scholars, and antimodernists—the antimodernists were in the strongest position, institutionally, at the end of the 1980s, given that theirs was the dominant orientation at CES. Faithful scholarship, however, was rapidly rising, while the new Mormon history was in retreat.

The early- to mid-1990s were a period of intense contestation in the Mormon intellectual milieu on several fronts. By the time the dust settled, scholars and institutions that embraced faithful scholarship had achieved a dominant status and, with that status, access to material resources and political clout surpassing those of any other camp along the intellectual spectrum. Despite criticism from leading antimodernists at CES, who feared that FARMS’s scholarly approach to the Book of Mormon was a slippery slope away from faith and testimony, FARMS’s success at defending orthodoxy and winning a good name for the Church through its contributions to Dead Sea Scrolls scholarship did much to convince Church leaders and members of the value of faithful scholarship. As already noted, the debate between antipositivists and defenders of the new Mormon history ended after 1994, with the antipositivists taking the last word. And a succession of controversies in the early 1990s clarified and enforced the boundaries of orthodoxy in ways that placed revisionism beyond the pale. These boundary-clarifying controversies included attacks by FARMS on revisionist anthologies published by Signature Books, the First Presidency Statement on Symposia, the exposure of the Strengthening Church Members Committee, and the “September Six” excommunications. The stigma attached to Sunstone, Signature Books, and, to a lesser degree, Dialogue as a result of these controversies encouraged LDS scholars to do their work in venues connected to BYU—primarily FARMS, the Smith Institute, and BYU Studies—thus enhancing those venues’ importance as centers for Mormon scholarship. The normative force of faithful scholarship was further strengthened by BYU’s academic freedom controversy. As BYU President Merrill Bateman explained, the Statement on Academic Freedom implemented by the administration in 1992 reflected a “paradigm” of “faithful scholars involved in extending the frontiers of knowledge.”

While rhetoric about “faithful scholarship” was not always perspectivist, the ascendance of faithful-scholarship rhetoric in general did lend greater weight to perspectivist versions of that rhetoric as exemplified by BYU Studies, the Smith Institute, and FARMS. A soft-focus pers- pectivist influence was evident as well in the Statement on Academic Freedom. By defining BYU as “an openly and distinctively LDS university” where “faithful Latter-day Saints . . . pursue knowledge from the baseline of religious belief,” the statement linked rhetoric about faithful scholarship to the promotion of knowledge grounded in LDS particularity. It is evident from the sources cited in the statement that its authors had encountered the work of Michael W. McConnell and George Marsden, scholars who, in the early 1990s, attempted to turn postmodernism against itself by invoking its pluralist values on behalf of conservative religious perspectives. McConnell’s and Marsden’s arguments took the form of a protest: that pluralists who championed the distinctive perspectives or worldviews of marginalized groups (women, racial minorities, sexual minorities, colonized peoples) withheld that same tolerance from religious worldviews—by which McConnell and Marsden meant, more specifically, conservative religious worldviews. Marsden, a fundamentalist Presbyterian by upbringing and lifelong Calvinist, expressed the argument this way in a First Things article cited in BYU’s Statement on Academic Freedom:

The post-1960s, postmodernist generation . . . [d]espite their rhetoric of pluralism and their deconstructionist ideologies, . . . behave as though they held Enlightenment-like self-evident universal moral principles. As with the old champions of liberal consensus, they want to eliminate from academia those who do not broadly share their outlook. . . . If in public places like our major universities we are going to operate on the premise that moral judgments are relative to communities, then we should follow the implications of that premise as consistently as we can and not absolutize one, or perhaps a few, sets of opinions and exclude all others. In other words, our pluralism should attempt to be more consistently inclusive, including even traditional Christian views.

Essentially, McConnell and Marsden accused the postmodern academy of reverse discrimination. Both raised the specter of a homogenizing secularism that, by threatening to destroy religious higher education, belied liberal or postmodern professions of pluralism. Writings of Marsden and McConnell—especially McConnell—were influential in shaping the Statement on Academic Freedom’s notion of “institutional,” as distinct from individual, academic freedom, meaning the imperative to protect the university’s distinctive religious identity from secularization. That imperative motivated the dismissal of professors whose work administrators perceived as incompatible with the Church’s teachings or standards.

The assertion that the postmodern turn in contemporary scholarship ought to translate into legitimacy for Mormon particularity was echoed by young up-and-coming LDS scholars in the 1990s and 2000s. In a 1995 Dialogue article, LDS literary critic Michael Austin invoked the turn toward the particular in literary studies to make a bid for bringing Mormon literature into the American canon alongside other minority literatures. By analogy to the hyphenated designations for other American ethnic groups, Austin coined the expression “Mormo-American” to encapsulate “the claim that we, as Mormons, and particularly as American Mor mons, represent a cultural entity whose traditions, heritage, and experience deserve to be considered a vital part of the American mosaic. . . . [A]nyone who doesn’t think we deserve our own place in the canon is a ‘Mormophobe’ whose position should not be taken seriously by an academy that values tolerance, difference, and diversity.”

A decade later, LDS graduate students Reid Neilson and Jed Woodworth drew inspiration from George Marsden’s argument on behalf of Christian perspectives in the academy as expressed in the postscript to his historical study of secularism in higher education, The Soul of the American University. (Marsden had already made the same argument in his First Things article quoted in BYU’s Statement on Academic Freedom.) Neilson and Woodworth credited Marsden with helping to create “a climate more favorable to religious views than in years past.” They were also heartened by a reiteration of Marsden’s appeal to particularity made by Marsden’s colleague, fellow evangelical historian Grant Wacker, who specifically championed the academic legitimacy of faithful LDS scholarship. “There is no reason,” Neilson and Woodworth quoted Wacker as saying, “that a . . . Mormon spin on the past should be any less acceptable in the academic marketplace than a Freudian or Marxist one.” A more senior LDS scholar, BYU history professor Grant Underwood, quoted Marsden to assure a largely LDS audience at the 2005 Joseph Smith symposium at the Library of Congress that faithful scholarship was compatible with academic methodologies. “Scholars today,” Underwood asserted, claiming Marsden as his example, “do not rule it out as a theoretical possibility” that Joseph Smith was “God’s spokesman.” Underwood was less interested than Neilson and Woodworth in Marsden’s use of postmodernism; but for all three of these LDS scholars, Marsden offered hope that distinctively LDS perspectives could gain a hearing in the contemporary academy.

Ambiguities and Ambivalences

The invocation of Marsden provides an entrance point into exploring the ambiguities and ambivalences that surround faithful scholars’ use of postmodernism. Marsden cites the postmodern turn toward positionality to argue that, since postmodern scholars have abandoned Enlightenment pretenses to objectivity and neutrality, “the contemporary academy on its own terms has no consistent grounds for rejecting all religious perspectives.” That is, the academy cannot exclude religious perspectives without violating the principles it professes to embrace. Simply put, Marsden charges the academy with not playing by its own rules. This is not to say, however, that Marsden embraces postmodernism. On the contrary, Marsden believes that “relativistic postmodern anti-realist naturalism” threatens the moral center of the academy and of society more broadly. Ultimately, Marsden does not want to bring Christian perspectives into the academy in order to enrich a perspectivist kaleidoscope of “truths.” Rather, Marsden seeks to bring Christian influence into the academy as part of an ambitious project to make Christ’s sovereignty visible over the entire domain of human existence. Like Midgley and Bohn, Marsden enlists postmodern arguments in support of an agenda that is more antimodern than postmodern.

Marsden’s opposition to “relativistic postmodern anti-realist naturalism” finds an analogue in a strain of cultural conservatism that, during BYU’s academic freedom controversy, advocated faithful scholarship as a counteragent to moral and epistemological relativism. The citation of a number of articles from the journal First Things in the Statement of Aca demic Freedom is one sign of a connection between some versions of faithful-scholarship rhetoric and the “culture wars” of the 1990s, when conservatives moved to check what they perceived as the pernicious excesses of multiculturalism and an oppressive regime of political correctness. The need for BYU to preserve its religious identity in order to resist the trend toward moral relativism in higher education was a key theme of Merrill Bateman’s inaugural address as BYU president; Bateman drew heavily from a First Things article on the subject by Gertrude Himmelfarb. Provost Bruce Hafen likewise promoted conservative cultural politics when he held up First Things as a model for the kind of work he would like to see faithful scholars at BYU produce. A similar politics fueled calls for “faithful criticism” from English professor Richard H. Cracroft, director of BYU’s Center for the Study of Christian Values in Literature. The BYU English Department, a hotspot for academic freedom controversies, was deeply divided for and against postmodern modes of critical theory—feminist, multiculturalist, deconstructionist, and so on. Cracroft, who had long been a voice calling for orthodoxy from LDS writers and critics, became strident during the early 1990s in denouncing “Marxism, Deconstructionism, Post-Structuralism, [and] Feminism,” together with “immoralism, atheism, nihilism, negativism, perversity, rebelliousness, doubt, disbelief, and disorder.” “We need Faithful Critics,” Cracroft exclaimed, “who cultivate the presence of the Holy Ghost” and reject the “creeds of secularism.” Yet another expression of conservative opposition to postmodernism was BYU law professor Lynn Wardle’s complaint, during the academic freedom controversy, that some faculty wanted to turn BYU “into a bastion of post-modern ideology.”

For cultural conservatives in this vein, promoting faithful scholarship at BYU meant taking a stand against deconstruction, identity politics, and the flurry of -isms that threatened to undermine the great moral and intellectual traditions. This was a decidedly anti-postmodern version of the faithful scholarship project. But how do the anti-postmodern sentiments voiced by Merrill Bateman, Bruce Hafen, Richard Cracroft, and Lynn Wardle relate to the postmodern bids for legitimacy made by younger scholars such as Michael Austin, Reid Neilson, and Jed Woodworth, or to the loose perspectivism embraced by BYU Studies, the Smith Institute, and FARMS? Do they represent opposing LDS attitudes toward postmodernism? Or is the coexistence of these voices symptomatic of a lack of clarity among LDS academicians about the tensions involved in attempting to harness postmodern language and sensitivities in the service of orthodoxy?

When LDS scholars invoke postmodern trends to support faithful scholarship, it is not always clear whether they have somehow reconciled orthodox LDS faith with postmodern understandings of truth as social construction60—or whether, like George Marsden, they are simply using the postmodern turn to argue that the academy “on its own terms” is obliged to recognize faithful scholarship as legitimate. Richard Bushman seems to hint at the latter option when he describes himself as “tak[ing] advantage of the postmodern moment” for the sake of undermining “positivist science.” Elsewhere, though, Bushman comes across as am bivalent about the potential for purchasing academic legitimacy on postmodernism’s tab. In a 2001 BYU Studies article (later distributed to the media by LDS Public Affairs during the Joseph Smith bicentennial), Bushman recognized that the postcolonialist impulse to see “colonized people on their own terms” had yielded a “broad tolerance” that makes it possible for non-LDS scholars to approach Mormonism sympathetically despite the faith’s challenging historical claims. It was thanks to this postmodern tolerance that non-Mormon presses were willing to publish Bushman’s Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism and Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, studies that reproduced LDS understandings of the Restoration. But the terms of this sympathy worried Bushman. “By giving in to tolerance,” he warned, “there is a danger that Mormonism will be treated like voodoo”—publicly respected, privately dismissed. Repeating a doubt he had first expressed in the late 1960s, Bushman wondered if perhaps Mormons hadn’t been better off back in the days when the historiography of Mormonism was racked by pro- and anti-Mormon polemics. “Wouldn’t we prefer,” Bushman wrote in 2001, “to be taken seriously enough to be directly opposed rather than condescended to?”

In the field of religious studies, which is the sector of the academy where emerging Mormon studies is finding its institutional home, the postmodern turn has produced a number of trends that, in theory at least, could gain a hearing for orthodox accounts of Mormonism in non-Mormon forums. As Russell McCutcheon, a critic of these trends, has observed, “Postmodern critiques of authority are often appropriated by scholars of religion acting as caretakers and used to legitimize and relativize all contexts; in other words, because we are all contextually bound, or so the argument goes, then all viewpoints deserve equal time in any one discourse.” Faithful scholars make their own versions of this move when they cite the postmodern rejection of claims to objectivity and neutrality to legitimize scholarship from an orthodox LDS perspective. LDS scholars making this move have found allies among the “new evangelical historians” like George Marsden, Mark Noll, and Grant Wacker, who model similar arguments to legitimize scholarship from an avowed Christian perspective. Marsden and Wacker have specifically championed the right of faithful LDS scholars to bring their “spin on the past” into the academy. (At the same time, Marsden has expressed reservations about faithful LDS scholarship, discussed below.) Other scholars outside Mor monism have used postmodern critiques of the Enlightenment to push for relaxing the boundaries between theology and religious studies, which, though often conflated by the public, are organized as separate disciplines. In theory, this push could support efforts to bring faithful LDS scholarship into the academic mainstream by bestowing a greater measure of academic authority on the confessional discourses of religious insiders.

The impact of the phenomenology of religion on the field of religious studies, especially during the 1960s, when religious studies departments proliferated, has produced a widespread sense among scholars that they ought to “take seriously” the perspectives of religious insiders or to study religions “on their own terms.” Not coincidentally, two of the scholars widely perceived as Mormonism’s most sympathetic outsider observers, Jan Shipps and Douglas Davies, self-consciously use phenomenological methods. Although it would be a stretch to call phenomenology of religion “postmodern,” the sympathy it inculcated for religious insiders’ own accounts of their traditions has been reinforced in recent decades by intellectual traditions that are indisputably postmodern. Karen McCarthy Brown, author of a highly influential ethnography of Vodou that was influenced by postmodern and feminist critiques of her field’s traditional methodologies, argues that scholars have an ethical imperative to allow “the people who are being studied . . . to speak for themselves whenever possible.”

Postcolonialism provides another vocabulary for legitimizing insider self-representations. Jewish studies professor Peter Ochs argues that religious studies scholars echo “colonialist behaviors we otherwise disavow” when they “resituate [religious phenomena] within conceptual universes of our own devising.” To “repair these colonialist tendencies,” Ochs calls upon religious studies scholars to make room in the classroom for religious traditions’ self-representations: “how they tend to describe and account for their practices.” American religious historian Ann Taves has written of the “danger” that scientific vocabularies for explaining religion will “subsume the experience of others into what becomes, in effect, a reified colonizing discourse,” thus “violating the lived experience” of the religious. There are affinities between Taves’s concern and antipositivist David Bohn’s warning that “histories of the Mormon past that seek to account for the sacred in secular terms . . . necessarily do violence to the past they are seeking to re-present.” Taves has expressed her commitment to “level[ing] the playing field” between “religious and secular perspectives”—an especially significant statement for faithful scholars given that Taves was a member of the Mormon studies council at Claremont until she left to take a position elsewhere.

While these developments in religious studies may be encouraging to faithful scholars who aspire to greater status for their work, it remains to be seen how far faithful scholars can actually go on the strength of these postmodern trends. As there is ambivalence among faithful scholars about postmodernism, so there is ambivalence among postmodern scholars about faithful Mormon scholarship. Religious studies scholars who champion insider perspectives or a more welcome reception for theology commonly qualify their advocacy with concessions to certain standards of academic rigor, rationality, or plausibility. These standards are not precisely defined. However, they probably rule out orthodox LDS beliefs about Israelite colonies in ancient Mesoamerica and the miraculous translation of golden plates, judging from the fact that non-Mormon scholars who write on these subjects routinely signal their skepticism in a variety of ways, ranging from overt deprecation to subtle rhetorical distancing. Even George Marsden, who has specifically defended LDS scholars’ right to bring assumptions distinctive to their faith to mainstream scholarly venues, draws the line when it comes to claims related to the historicity of the Book of Mormon. “Some of their scholarly concerns,” Marsden diplomatically explains, “such as those regarding the ancient Native Americans, may have to be addressed to other Mormon scholars alone.” Marsden’s advocacy for religious perspectives in scholarship is not prepared to go so far as to argue that non-LDS scholars should have to engage historical claims made by the Book of Mormon. Just how broad is postmodern tolerance, really? The boundaries that emerge from the negotiations involved in establishing Claremont’s Mormon studies chair will prove a revealing case in point. Thus, the emergence of Mormon studies has the potential to force clarity among religious studies scholars about the credibility of insider perspectives—or at least will expose the unspoken limits in scholars’ willingness to take those perspectives “seriously.”

As faithful scholars have run up against those limits, a curious thing has happened. They have adapted by reverting to rhetorical moves reminiscent of the new Mormon history. LDS scholars who move frequently in mainstream academic circles sense what can and cannot be said credibly in those circles. Elsewhere, I have demonstrated that faithful scholars seeking to reproduce an orthodox LDS perspective on the Book of Mormon in scholarship written for non-Mormon audiences (Richard Bush man and Terryl Givens are the leading examples) have always done so in ways that appear to disavow intending to actually persuade readers of the truth of this perspective. In 2001, Bushman had asked whether “believing biographers” wouldn’t “prefer to have the question of authenticity laid squarely before our readers.” But he declined to lay that question squarely before readers of Rough Stone Rolling, published three years later. Instead, Bushman told readers that he would be describing events from an LDS perspective—without the “purportedlys” and other qualifiers that had offended critics of the new Mormon history—in order to “reconstruct the beliefs of [Joseph Smith and his] followers as they understood them.” This was the familiar project of phenomenology of religion. It was, in fact, the project Jan Shipps had pursued twenty years earlier in Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, a project for which she was criticized by Louis Midgley.

Faithful scholars assure each other that the “perspective” of LDS orthodoxy is as legitimate a foundation for scholarship as the perspectives of feminism, Marxism, or any other established variety of critical theory. At the same time, they recognize in practice the extent to which the Enlightenment heritage continues to define the boundaries of credible academic discourse. Furthermore, as the emergence of Mormon studies at non-Mormon institutions prompts faithful scholars to seek common ground with non-Mormon colleagues, faithful scholars have begun to adopt lines similar to those that were criticized in the 1980s and early 1990s by proponents of more conspicuously and militantly LDS approaches to scholarship. When the new Mormon historians sidestepped the prophet/fraud debate in the 1970s and 1980s, Midgley and Bohn denounced this approach as treacherous and epistemologically impossible. In contrast, in 2006 Robert Millet of BYU Religious Education declared himself satisfied that scholars were at least “thinking seriously” about Smith even if they didn’t accept him as a prophet. This was a departure from Millet’s 1987 insistence that the story of the Latter-day Saints “must be told in the Lord’s own way if it is to accomplish what the Savior and his anointed servants have envisioned.” In 2004, Richard Bushman described himself as someone who has “to fight on two fronts”: against “unbelieving” historians who find his faith absurd and against “self-satisfied” Latter-day Saints who expect their historians to “confir[m] the traditional Mormon view.” In representing himself as standing between secularism and uncritical traditionalism, Bushman replicated a move that Leonard Arrington and Thomas Alexander had attempted twenty years earlier, only to encounter much heavier criticism than has fallen on Bushman. Ironically, after defining itself over against the new Mormon history during the 1980s and 1990s in the name of postmodernism, faithful scholarship now shows signs of being pushed by the limits of postmodern tolerance back in the direction of its former foil.

Conclusion

Postmodern appeals among “faithful,” or orthodox, LDS scholars have taken two forms. Beginning in 1981, antipositivists such as Louis Midgley and David Bohn deployed antifoundationalist critiques of Enlightenment claims to objectivity as an instrument to undercut the new Mormon history’s efforts to produce scholarship that was neutral vis-à-vis polemics about LDS claims to revelation. The antipositivists argued that, because knowledge is never neutral, LDS historians should abandon efforts “to understand as scholars of any faith or no faith would seek to understand” and should instead embrace the role of defending the faith from naturalistic or secularist attacks. The second kind of postmodern appeal among faithful scholars has been a diffuse perspectivism, expressed in scholars’ commitment to working from a distinctively LDS “perspective” or “point of view.” This perspectivist rhetoric gained increased currency during the 1990s as a faithful-scholarship orientation became normative and rewarding for Church-affiliated scholars. Echoing arguments by other religious conservatives, LDS perspectivists maintain that, in the postmodern academy, an orthodox Mormon perspective ought to be as acceptable as any other form of epistemological particularity or positionality.

There is no question that the postmodern turn has benefited Mormon studies in the sense that it has generated interest in scholarship on religious minorities. There’s also no question that postmodern lines of inquiry could lead to innovative and illuminating Mormon scholarship. How successful postmodern appeals will be at securing academic legitimacy for faithful Mormon scholarship is less certain. The uncertainty is due partly to a lack of clarity within religious studies regarding just how seriously scholars should “take seriously” extraordinary claims by religious insiders. The uncertainty is also due to LDS scholars’ own unsettled attitudes toward postmodernism. No doubt many faithful scholars find it gratifying to be able to cite canonical postmodern authorities against the Enlightenment rationalism that would dismiss LDS faith as self-evidently absurd. At the same time, most faithful scholars do not appear to share the left-leaning politics that postmodern scholarship usually promotes in practice. Entirely apart from questions of their philosophical consistency, postmodern appeals on behalf of cultural conservatism or religious absolutism are an odd duck, politically speaking.

I suspect that faithful scholars, like other religious conservatives, will find that postmodern appeals work best at assuring intellectually inclined insiders of the credibility of the faith and at discomfiting Enlightenment liberals within the Mormon community. If even George Marsden balks at admitting faithful scholarship on the Book of Mormon into the mainstream of academic conversation, it would appear that the prevailing politics of knowledge militates against non-Mormon academicians being persuaded to put orthodox accounts of the Restoration on a par with secular accounts. Even avowed postmoderns can tolerate only so much deconstruction of the Enlightenment edifice within which they have built their careers. The fact that faithful scholars have begun to shift back to ward rhetorical moves associated with the new Mormon history—the very moves that antifoundationalists attacked—suggests that faithful scholars must capitulate to secular ground rules more than they might prefer as the price for participating in the academic mainstream, postmodern challenges to the Enlightenment notwithstanding. Leonard Arrington’s style of Mormon scholarship may yet see a comeback; Louis Midgley, I imagine, will not be pleased.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue