Blog

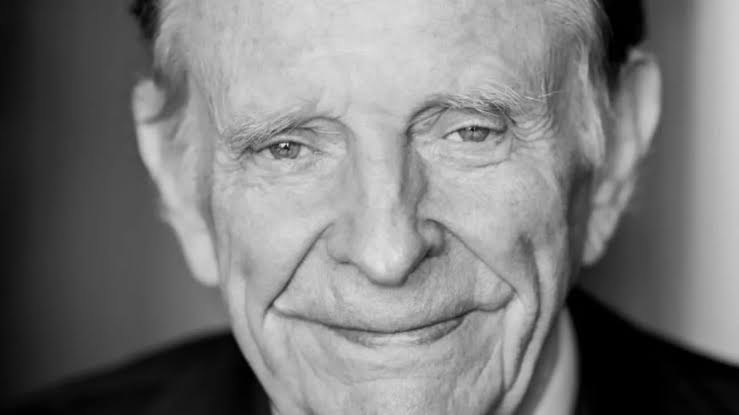

Bushman on Friendship

September 5, 2011

Richard Bushman: My thanks to Grant Underwood for conceiving this panel and going to all the work to put it together under the auspices of the American Society of Church History. It was a generous act of friendship on his part. I am delighted also that Skip, Gordon, Catherine and Laurie, agreed to comment. It is a little uncomfortable for me to be the center of attention. But it is gratifying nonetheless to hear so many interesting people reflect on what I have written. My intention is to enjoy it for a few minutes and then forget everything that has been said.

I want to use the occasion to reflect a little on what this all means. At the Harvard commencement the president welcomes the new graduates into the company of educated men and women. Today I wish to celebrate the company of men and women historians. I have been teaching American religion at Claremont this past year, and it has brought great pleasure to find how many of the books I assign were written by people I know. I know their styles, a few idiosyncrasies, and something of what matters to them. Although I see them only occasionally, I still feel that we constitute a circle of friends as well as group of scholars. Perhaps one of the most important parts of becoming an historian is to be initiated into that circle.

In forming these academic friendships, our books are our surrogate selves, our initial introductions to one another. I rode up in an elevator at a convention once with David Hall and glancing down at the name tag of another conventioneer, David snapped out two titles. There was instant recognition. Had there been time there could have been conversation. Pauline Maier once said that for her the payoff for all the work was access to this comradeship.

In this company of historians, person and writing merge. As we become better acquainted, we begin to hear personality coming through the words on the printed page. “So like her,” I say to myself. Knowledge of the person helps us to understand the writing better, and the writing opens up the person. The combination creates a kind of intellectual kinship that is one of the great rewards of our profession.

In the interests of furthering our sociability, I want to speak about this intermingling of writing and life in my own work. As the years go by, my historical work, in my own mind, blends more and more with biography. I see my writing emerging from a life and not just from a discipline. Careful as I tried to be in reading the evidence, what went on the pages of the histories I have written is recognizably my own.

From Puritan to Yankee, for example, though written as a kind of bottom up analysis in the spirit of the town studies coming out in the 1960s, also grew out of my Mormon upbringing in Portland, Oregon. When I was choosing a dissertation topic in the late fifties, most of the important work dealt with high politics or high intellectual history. I was not attracted to that kind of history. I wanted to work at another level, not because writing about ordinary people was in the air, but because I was interested in people like the ones I had grown up with–my family friends, and fellow church members in Portland. There was a huge gulf between my life in Portland and my life at Harvard. I actually loved Cambridge and was more myself there than anywhere I had been, but still the Portlanders were my people and represented the real world in my mind. It was that world I wanted to return to as I began my research.

I hit on the Great Awakening as the central problem of my work because it seemed like an exceptional opportunity to get inside the minds of a large number of otherwise inarticulate people. I had sat in testimony meetings in my Latter-day Saint congregation and heard one person after another stand and talk about his or her innermost problems as they were encouraged to do on the first Sunday of each month. Listening from my place at the sacrament table where young priests sat to bless the bread and water, the adults’ expression of their inner turmoil was reassuring. Their struggles resonated with my own adolescent miseries. Remembering those occasions, it was not a far stretch for me to see in the Great Awakening an opportunity to gain access to the inner lives of ordinary eighteenth-century people like my Mormon brothers and sisters in Portland.

Not just the subject, but my explanation for the revivals came out of my early life. In the book I posed the question why were so many eighteenth-century people willing to hear preachers tell them they were hopeless sinners and believe it? Why the pervasive guilt that must have lain beneath the consciousness of thousands of hearers? The answer in From Puritan to Yankee was that many in the population had resisted the authority of the standing order–in moving out of the town centers, in breaking from the churches, in seeking wealth over piety. They had not followed the Puritan practice of weaned affections–diligently pursuing their earthly callings without giving their hearts to them–but had sought material well being to the point of repeated conflicts with civil and ecclesiastical authority.

Other historians at the time when I wrote had seen the Great Awakening as resistance to oppressive authority, and it was surely that. What I added to the mix was acknowledgment that resistance to authority produced guilt. People paid a price for standing up to authority, I believed, and that came right out of my Mormon upbringing. Mormons live in a structured world of church and family authorities who are not easy to resist. They are benevolent figures, dedicated to the well being of those in their charge. Talking back to them is like talking back to a father whom you know truly loves you. The price of resistance to that kind of power is guilt. It is heroic and liberating to resist authority, but also costly. I cast this Mormon view of authority onto the Puritans and came up with the guilt that fed the Awakening.

That same dynamic ran through King and People in Provincial Massachusetts. Initially I thought of it as an extension of From Puritan to Yankee. The study I began on Connecticut would extend into Massachusetts and focus more on politics than on religion. I sensed a similar psychological structure in revival religion and revolutionary rebellion. Both began with a tyrant–a God who unfairly condemned the sinners he had made and a king who oppressed his subjects. The language in both contexts, religious and political, sounded the same to me. I thought I could write a book that joined the two, though the outcome was different in each case. Revival converts ultimately reconciled themselves to God. They admitted their unworthiness and found a way to love the God who threatened to cast them off. The revolutionaries never made peace with the tyrant king. They destroyed him, smashing his image, and putting themselves on the throne. My work with Erik Erikson during a two-year post-doctoral fellowship at Brown University was an attempt to explore the psycho-dynamics of these two struggles.

The book I had planned never was written. I drew back for two reasons. The first was that I began to question my subject. Who and what was I writing about? I feared it was some abstract “mind” of the culture. Scholars spoke of the American mind in the 1950s. In the 1960s, as the sociological turn occurred, we wanted to treat real people who could be named and numbered. My tyrant-ridden mind seemed to be reside somewhere off the planet. I wanted to root my arguments in real people and events. Hence my turn to political culture and the realities of Massachusetts politics.

The second reason for the switch was my inability to sustain a narrative. I did a ton of research in political and religious documents, and each summer set out to write. I would turn out forty or fifty pages and the narrative would sink into the sand like river water in the Great Basin. I could not figure out where I was going. I came to doubt my powers as a historian. Where had the historian who produced a Bancroft Prize winner on his first try gone to? I thought of leaving the university and going to work in the Church historian’s office.

I was saved by the Bicentennial of the American Revolution. Every early Americanist in the world was asked to lecture during 1976. What was I to lecture on? All I had was the pile of notes I had accumulated over the past decade. I was forced to ask what is it I really want to say. By staring at texts in the microfilm readers for hundreds of hours, I had discovered the themes of dependence and independence that run through King and People. I got down to bare bones of my thinking, cobbled together the lectures, and by the end of the Bicentennial year I had the outline of a book. I was saved not by the bell but by the celebration.

To my eye now, every one of my books has personal dimensions. The Refinement of America is a treatise on my mother’s and my grandmother’s culture. The book is shot through with ambivalence about the merits of gentility. In the book gentility is portrayed as both a civilizing ideal and a meretricious and snobbish device for enforcing class boundaries. My grandmother was the daughter of a German school teacher who had taught art in a Dresden gymnasium before migrating to Utah as a Mormon convert. There his attempts at teaching school for tuition failed, and he became a shoe salesman. My grandmother as a girl worked in a shoe factory and had no education, but she created a home where her artist father’s frustrated tastes were made manifest. She had a hand for making everything beautiful including the furniture she finished herself. To my youthful eyes, her living was was gorgeous. My mother grew up aspiring to make everything beautiful too–the leading theme of genteel culture. I admired her but in a typically boyish way fought her as she imposed those standards on me. That prepared me to partake of the disillusionment with gentility in the larger culture as I was growing up. I was aware even then of class divisions and didn’t like them. The outcome in the book as in my life was a kind of ironic distance between me and gentility, both in my life and in the book–embracing it as the culture of my mother and grandmother while lamenting its superficialities and hurtful exclusions.

Besides recognizing gentility as an instrument of class power, I also saw it in a religious light. The book actually rests on a theology of culture I learned from Reinhold Niebuhr. While in graduate school I had come under the influence of Niehbuhr’s The Nature and Destiny of Man: A Christian Interpretation. Niebuhr argued that humans combine a yearning for the infinite with the reality of finitude. They aspire to be gods when they are actually confined by human limitations and corruptions. Many of the highest human achievements grow out of this drive for power, but also the evils of human history. The yearning for the infinite, manifest itself in the noblest reaches of art, science, and politics but equally in the drive for power that underlies the most horrible crimes. I read into the genteel urge for elevation, for beauty, for perfect grace, another symptom of the yearning to transcend human finitude. It was an elevating aspiration, noble and generous at its best, but prideful, vain, superficial, and invidious in many of its manifestations, a source of hurt, shame, and social conflict. It was both godly and devilish. I probably should have dedicated the book to Reinhold Niebuhr.

My personal involvement in my early books might never occur to a casual reader; not so with Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, my biography of the Mormon prophet. It probably appears to be the most personal of all my books. Here I bring my personal religious beliefs into the open in directly addressing Mormonism’s most controversial figure, Joseph Smith. Readers both Mormon and non-Mormon have imagined this as a difficult book to write, since it attempts to confront the whole Joseph Smith–his extravagant claims to visions and revelations, his polygamous excursions, his boosterism and braggadocio, his engagement with magic, his temper and raw emotional force as well as his religious ingenuity and his capacity for evoking the sacred. Was it not hard for you as a believing Mormon, I am asked, to lay it all out for your readers? Weren’t you challenged in your beliefs; weren’t you worried about what other Mormons would say; weren’t you divided in yourself?

Strangely that was not my experience in writing the book. I was not constantly asking how do I handle this hot potato or that. I simply gathered what information I could from the sources and wrote the story. There were no long debates with myself about what to include and what not. Everything I thought relevant I put in. Virtually every reader will sense my sympathy for Joseph Smith, but that is how I write about all historical subjects. My inclination is to give the historical subject’s own perspective priority, rather than to act as critic. I felt I was treating Joseph Smith as I would treat Benjamin Franklin were he the subject. Anything that revealed something about Smith’s character or his plight went into the book.

I have always applauded Fawn Brodie for creating a Joseph Smith who was a credible human being and not a caricature of religious fanaticism as earlier works had presented him. She made him a pious fraud, but intelligible and sympathetic, a believable person. I wanted to portray a believable Joseph Smith too, but one who was sincere, a man who thought he was a prophet and carried that conviction through his life. On the basis of the evidence alone, I am not sure that you can choose between the two, but I wanted readers to have a choice. That simple aim made the book relatively easy to write. I was aware that many would not follow me through the book. I asked them to accept more than they could stomach. But the simple premise of Smith’s sincerity guided me through the tangled story.

So what have I offered you? Probably the least trustworthy of all histories is a writer’s account of his own motivations. How can we take a writer’s stories seriously when we know all of us have to protect ourselves and make ourselves presentable to the world? The need for myth making is all the greater when we write about something we cherish as much as our own work. But trustworthy or not, I think it useful to tell our stories about ourselves as I have tried to do today. I go back to the Mormon testimony meetings I attended as a boy. When those people stood to account for themselves, they spoke from a mythic world spun from their culture and their psychic pain. I can see now that they were spinning the stories to make themselves believable and the world sensible. Even so, as I listened, I felt that I encountered life at a deeper level. I was hearing human beings trying to create meaning out of the raw materials of their experience.

In something of the same way I listen for the deep bass notes in the writings of my fellow historians. I value their skill, their industry, their pursuit of truth, but I read their books as more akin to my Mormon friends than you would think. They too are constructing mythic meanings for themselves and their readers. However scholarly, they are trying to make themselves believable and the world sensible. You will understand then why I hear in the works of my esteemed colleagues a kind of testimony bearing, and why I value their friendship all the more for that.

Back to all blog articles

Back to all blog articles