Polygamy

Introduction

Welcome to our curated collection of articles and discussions on the multifaceted topic of polygamy. This collection brings together voices from diverse backgrounds, offering a nuanced exploration of the experiences, challenges, and ethical considerations associated with polygamous unions.

Join us on this thought-provoking journey as we engage in a respectful and insightful dialogue about a topic that has shaped and continues to influence societies worldwide. Through these curated resources, we aim to foster understanding, promote empathy, and encourage meaningful conversations surrounding polygamy.

Queer Polygamy

Blaire Ostler

Dialogue 52.1 (Spring 2019): 33–43

Ostler addresses the problems with what she terms the “Standard Model of Polygamy.” She discusses how these problems might be resolved if it is put into a new type of model that she terms “Queer Polygamy.”

According to many accounts of LDS theology, polygamy, also called celestial marriage, is a necessary mandate for the highest degree of celestial glory. Doctrine and Covenants sections 131 and 132 tell us that celestial marriage and the continuation of the human family will enable us to become gods because we will have endless, everlasting increase (D&C 132:20). The Doctrine and Covenants gives a direct warning that if we do not abide by the law of polygamy, we cannot attain this glory (D&C 132:21). Likewise, prophets have stated that theosis and plural marriage are intimately intertwined. Brigham Young, the most notable advocate for mandated polygamy, stated, “The only men who become Gods, even the sons of God, are those who enter into polygamy.”[1] However, he also wrote, “if you desire with all your hearts to obtain the blessings which Abraham obtained you will be polygamists at least in your faith.”[2] It is interesting that he uses the words “at least in your faith.” Was this to suggest that if a man cannot practice polygamy on earth, he will in heaven? Or is this to suggest a man may never enter into a polygamous marriage, but may live the spirit of polygamy in his heart? Later, Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal that “President Young said there would be men saved in the Celestial Kingdom of God with one wife with Many wives & with No wife at all.”[3] Woodruff also wrote, “Then President Young spoke 58 Minutes. He said a Man may Embrace the Law of Celestial Marriage in his heart & not take the Second wife & be justified before the Lord.”[4] What is to be made of these statements? How can one embrace the spirit of polygamy, the law of celestial marriage, but remain monogamous with one wife or even no wives?

This paper will refer to the sex-focused, androcentric, patriarchal, heteronormative model of polygyny as the Standard Model. At a glance, the Standard Model is highly problematic. Though the Standard Model tends to dominate discourse, a more creative interpretation of what the spirit of polygamy includes may offer new insight into what celestial relationships might look like. I’m suggesting a way to reconcile diverse desires for celestial marriage under a new model I call Queer Polygamy, which encompasses the spirit of polygamy without mandating specific marital relations. I will begin with an expository of the Standard Model of polygamy followed by an expository of the Queer Polygamy Model and demonstrate how plural marriage may be redeemed to accommodate diverse relationships and desires, as Brigham Young suggests. I will then point out five common concerns with the Standard Model of polygamy and how the Queer Polygamy Model address them.

The Standard Model of polygamy is often and reductively described as one man having multiple wives. The man will continue to increase in power and dominion according to the number of wives and children he accumulates. This means he is eternally sealed to all his wives and children as a god, like Heavenly Father, who also must have entered into plural marriage. To attain the highest degree of celestial glory and have eternal increase, a man must enter into polygamy. The Standard Model focuses exclusively on the man or patriarch with little regard to what others, especially women and children, desire.

This aesthetic of God and godhood is problematic for many reasons. This view paints a rather androcentric and domineering perspective of what polygamy might look like. Additionally, this makes God a patriarchal monarch whose power and glory aren’t shared with his family and community but used at the expense of his family and community. If God evolved into godhood as a lone patriarch, his power is not holy but tyrannical. This patriarchal model of God, polygamy, sealings, celestial glory, and heaven are not a vision of glory most of us would aspire to as Saints in Zion. The Standard Model also neglects doctrines concerning the law of consecration, theosis for all, and other communal practices of Zion. The people of Zion live together as one in equality (D&C 38:24–27; 4 Ne. 1:3), having one heart and one mind (Moses 7:8). The Saints of Zion together enjoy the highest degree of glory and happiness that can be received in this life and, if they are faithful, in the world to come. Zion can be thought of as a template for how gods become gods. Yet the Standard Model of polygamy doesn’t resemble anything Latter-day Saints might want to strive for. The God of the Standard Model sounds more like a venture capitalist accruing wives and children for self-glorification rather than the leader of a collective group of Saints living in pure love with one another. Community, diversity, nuance, and even sometimes consent[5] are lost in this simplistic narrative.

I believe queer theology is ripe with possibilities to reconcile our diverse aspirations toward Zion in a model I call Queer Polygamy, a model that can accommodate a potentially infinite number of marital, sexual, romantic, platonic, and celestial relationships. The phrase Queer Polygamy almost seems redundant. Polygamy is inherently queer according to contemporary monogamous marital expectations.[6] It is, by Western standards, a deviation from the norm. The word queer may also seem to imply that a person must necessarily be a member of the LGBTQ+ community for these ideas to apply, but this is not the case. Rest assured, heterosexual monogamous couples are an important subset under the umbrella of Queer Polygamy, just as Brigham Young suggested. A person with many, one, or no spouses may be included in this model. The use of the word queer in Queer Polygamy is to signify a more thoughtful and thorough interpretation of polygamy that would be inclusive of such diversity, and many of its manifestations would be rightly considered queer. You may initially find this model strangely foreign, but I believe it is in harmony with LDS theology, both logically and practically, as both scripture and past prophets have taught. The word polygamy is used to convey the plurality of relationships we engage in and to suggest that celestial marriage and eternal sealings include far more practices than heterosexual monogamy or androcentric polygyny. Eternal sealings among the Saints are inherently plural. Queer Polygamy is not in opposition to LDS theology but rather the fulfillment of the all-inclusive breadth that LDS theology has to offer.

The Standard Model of polygamy is problematic for multiple reasons, as many LDS feminists and queer theologians, like myself, have pointed out.[7] I will review five of the most common problems with the Standard Model, then demonstrate how they might be reconciled by adopting the Queer Polygamy Model. The five common concerns are that the Stand Model does not leave room for the following: (1) monogamous couples;(2) women, and other genders, who desire plural marriage; (3) asexuals, aromantics, and singles; (4) homosexual relationships; and (5) plural parental sealings.

First, an unnuanced reading of Doctrine and Covenants section 132 appeals to a patriarchal and androcentric model of polygyny built upon a hierarchy of men who will be given women, also called virgins, as if they were property (D&C 132:61–63). This exclusively polygynous model is a major concern for women who do not wish to engage in plural marriage without their consent, such as the case with “the law of Sarah” (D&C 132:64–65). By extension, the Standard Model does not leave room for couples who wish to remain romantically and/or sexually monogamous. However, there is room for monogamy in the Queer Polygamy Model. To demonstrate this, I’d like to refer to queer sexual orientations not as universal orientations or socio-political identity labels but as specific practices in specific relationships. For example, I identify as pansexual; however, in my relationship with my sister I am asexual and aromantic. Though I am pansexual by orientation, I engage in a specific asexual, aromantic, platonic relationship with her. This is not intended to mean that our relationship is void of depth, intimacy, love, commitment, and loyalty—quite the contrary. I feel all those things for my sister and more, but we have no desire for a sexual or romantic connection. This does not mean my sister is any less important to me than my husband, with whom I do desire a sexual and romantic relationship; it simply means the relationship dynamics are different between my sister and me and my husband and me. In the Queer Polygamy Model, I could be sealed to my sister in a platonic sealing for all eternity while also being sealed to my husband in a relationship that does include sex. I would be sealed to two people plurally, but I would still be practicing sexual monogamy. Thus, for couples who desire to practice heterosexual monogamy with one partner for all eternity, they may still be sealed to other persons they love plurally and engage in those other relationships asexually and aromantically. It is in this way that we can be sealed to our children. I am not only sealed to my husband, but I’m also platonically sealed to our three children. Not all sealings include sex, nor should they. Plural marriages, unions, and sealings among adults could also include plural, platonic sealings among several persons while the core couple still practices exclusive heterosexual monogamy.

Second, the account given in Doctrine and Covenants 132 does not explicitly address women who also wish to engage in plural marriages alongside their husbands. The exclusively polygynous model of polygamy can create a disturbing and problematic power imbalance among the sexes—especially for women in heterosexual relationships. Under the Queer Polygamy Model, plural sealings would be available to all consenting adults, not just men. As stated above, women are sealed to multiple people, such as children and parents, but I suggest that the policy allow women to be sealed to multiple adults whom they are not related to, just as men are afforded that privilege. Though the scriptures do not state that women may have more than one husband, that does not mean they can’t have more than one husband. In fact, more than one of Joseph Smith’s wives was also married to other men.[8] This shows there is room in our religion for women who desire to be married to multiple men, including heteroromantic, sexual, or asexual relationships. It would be up to the participants to decide the relationship dynamics of their sealing or marriage, just as Joseph Smith engaged in sexual relationships with some, but not all, of his plural wives. There are various reasons for plural marriage and/or sealings that do or don’t involve sex. Granted, legitimizing sexual relationships through sealings and/or ritual is important to avoid promiscuity in sexual relationships. Honesty and open communication are key to respecting the autonomy and volition of all participants—though not all past participants of polygamy practiced it in such a manner, namely Joseph Smith.

Third, a traditional interpretation of the doctrine of celestial marriage does not leave room for persons who do not desire marriage or are asexual and/or aromantic. However, there is room for asexual and aromantic sealings under the Queer Polygamy Model. Sealings of kinship, friendship, and love may be offered between persons who wish not to have a sexual or romantic relationship with others. Plural marriage for asexual persons could take the form of an asexual woman married to a heterosexual couple, or three asexual persons who wish to be sealed together in a plural marriage that doesn’t include sex. Again, sealing and/or marriage is not tantamount to sex. Asexual persons, or persons who wish to remain single, could be sealed to parents, siblings, friends, and other partners without committing to sexualized or romanticized notions of marriage and sealings.

Fourth, the Standard Model is aesthetically heteronormative—leaving out the experiences and desires for homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, and other queer persons. This may be one of the more difficult huddles to overcome, because the common perception of Mormon theology implies there is no such room for homosexual unions in celestial cosmology. I do not see why this must necessarily be the case. I have written several pieces about how we could reenvision our reductive views of creation to include homosexual relationships, creation, reproduction, procreation, and families.[9] In my view, homo-interactive creation, which includes homosexuality, is a required aspect of godly creation. If there is anything evolutionary biology has taught us, it’s that the creation of life and flourishing of the human species is far greater than heterosexual monogamy. I have no reason to think that God wouldn’t use natural means of creation to enable all life, goodness, relationships, parenting, and flourishing. If this is the case, it is possible for plural homosexual relationships to exist under the model of Queer Polygamy.

The Queer Polygamy Model leaves room for same-gender and same-sex sealings, whether they are platonic, such as with my sister and me, or homosexual, such as with two wives. Under the Queer Polygamy Model, plural marriage may include multi-gendered partnerships, such as sealings among sister wives that may or may not allow sexual relations between them. If a man is married to two women and the women are bisexual, they may choose to be sealed to each other and have a romantic and sexual relationship with each other as well as with their common husband. Likewise, a transgender woman might be married to a cisgender man and cisgender woman. If all identify as pansexual, it could be the case that they are all in a romantic and sexual relationship with one another. The takeaway is that gender is irrelevant to whether or not there is sexual activity in plural sealings—assuming there is no abuse, neglect, or harm being done to the participants. The purpose of the sealing isn’t to legitimize sexual behavior; the purpose of sealing is to legitimize the eternal and everlasting bonds that people share with one another, be they homosexual or otherwise.

Fifth, the Standard Model doesn’t leave room for children to have autonomy to be sealed or unsealed to diverse parents. In the Standard Model, children are property of their fathers and have little say about whether or not they may be sealed or unsealed to other parents. For example, a child born into a heterosexual marriage may be sealed to the parents, but if the father is gay, divorces his wife, and both marry other men, the child of the first marriage would have four parents—one biological father, one biological mother, and two stepfathers—but would only be sealed to the biological father and mother. Under the Queer Polygamy Model, the children could be granted plural sealings to both the biological parents and their husbands. The child would be sealed to three fathers and one mother, though the dynamics of the relationships are diverse and fluid among the parents. Essentially a child should be able to be sealed to all the parents they love. This is not the case under the Standard Model, which focuses on who the child belongs to in the eternities instead of whom the child desires to be sealed to. A child should not be forced to choose between fathers by mandates of heterosexual monogamy or patriarchal polygyny. Children with plural parents should be granted plural sealings for those who desire them. No child should have to divorce a parent eternally just to be sealed to another, just as no wife should necessarily have to divorce a husband to be sealed to a second. It is to the detriment of the child to assume they are inherently “owned” by their biological father alone when the child has the capacity to love more than one father and mother. Likewise, a child born to a family with three mothers and one father should have the opportunity to be sealed to all her mothers. Heaven isn’t heaven without all the people we love, and I trust God feels the same. If not, heaven becomes hell.

Now that we have a broader understanding of what diverse families and sealings could look like under the Queer Polygamy Model, the words of LDS prophets about families begin to taste sweet again. The family really is central to God’s plan—it is ordained of God. We are all part of one big family—God’s family. The family is far more than just one mom and dad. It is siblings, cousins, spouses, aunts, uncles, friends, grandparents, and the generations of persons who came here before you or me. The family is about creating bonds that extend into eternity as we connect with one another to become something greater than ourselves. Family is everything, yet too often people perceive family to mean something so narrowly defined. It is really a grand and beautiful quilt that envelops us all. Sealings under this broad quilt might include, but are not limited to, spouse-to-spouse sealings, parent-to-child sealings, law of adoption sealings, friendship sealings, and many more. Under the family quilt of Queer Polygamy, we are all interconnected in an infinite number of complex and beautiful relationships.

The spirit of polygamy is love of community. This is the law we must embrace as Saints in Zion if we are to become gods. The spirit of polygamy encompasses the diverse unions of the gods in all their complexity and intricacies. The spirit of polygamy includes, but also reaches beyond, the legitimization of sexual relationships. The spirit of polygamy means I might be sealed to my best friend regardless of whether or not we also share a sexual relationship. It means children may be sealed to all their fathers and mothers, be they biological or adoptive. It means it takes a village to raise our children. It means I may be sealed to a sister wife, not through my husband but with my husband. It means my husband may be sealed to his best friend while they enjoy a platonic, asexual, aromantic relationship. It means an asexual woman may choose to be sealed with a gay couple, independent of sexual activity, but still have a relationship full of meaning, emotional intimacy, and purpose. The spirit of polygamy means heaven isn’t heaven without all the people we love. It means infinite possibilities fulfilled by our infinite love—just like the gods, filled with a multiplicity of heavenly mothers, fathers, and parents that we have yet to imagine. I cannot imagine any God more beautifully Mormon than a God of both plurality and unity who welcomes all families into Zion as we strive to join the gods above.

[1] Brigham Young, Aug. 19, 1866, Journal of Discourses, 11:269.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “I attended the school of the prophets. Brother John Holeman made a long speech upon the subject of Poligamy [sic]. He Contended that no person Could have a Celestial glory unless He had a plurality of wives. Speeches were made By L. E. Harrington O Pratt Erastus Snow, D Evans J. F. Smith Lorenzo Young. President Young said there would be men saved in the Celestial Kingdom of God with one wife with Many wives & with No wife at all” (Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, edited by Scott G. Kenny, 9 vols. [Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985], 6:527 [journal entry dated Feb. 12, 1870]).

[4] Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 7:31 (journal entry dated Sept. 24, 1871).

[5] “The revelation on marriage required that a wife give her consent before her husband could enter into plural marriage. Nevertheless, toward the end of the revelation, the Lord said that if the first wife ‘receive not this law’—the command to practice plural marriage—the husband would be ‘exempt from the law of Sarah,’ presumably the requirement that the husband gain the consent of the first wife before marrying additional women” (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Plural Marriage in Kirkland and Nauvoo,” Oct. 2014).

[6] In this paper I will use the word queer according to its broad definition as anything strange, peculiar, odd, or deviating from conventional norms or societal expectations. If I am using the word queer as a referent to the LGBTQ+ community, I will use queer persons or queer community.

[7] Blaire Ostler, “A Feminist’s Defense of Polygamy,” personal blog, Oct. 27, 2017; Blaire Ostler, “The Problem is Patriarchy, Not Polygamy,” personal blog, Feb. 5, 2018.

[8] “Several later documents suggest that several women who were already married to other men were, like Marinda Hyde, married or sealed to Joseph Smith. Available evidence indicates that some of these apparent polygynous/polyandrous marriages took place during the years covered by this journal. At least three of the women reportedly involved in these marriages—Patty Bartlett Sessions, Ruth Vose Sayers, and Sylvia Porter Lyon—are mentioned in the journal, though in contexts very much removed from plural marriage. Even fewer sources are extant for these complex relationships than are available for Smith’s marriages to unmarried women, and Smith’s revelations are silent on them. Having surveyed the available sources, historian Richard L. Bushman concludes that these polyandrous marriages—and perhaps other plural marriages of Joseph Smith—were primarily a means of binding other families to his for the spiritual benefit and mutual salvation of all involved” (“Nauvoo Journals, December 1841–April 1843,” introduction to Journals: Volume 2, The Joseph Smith Papers). “Another theory is that Joseph married polyandrously when the marriage was unhappy. If this were true, it would have been easy for the woman to divorce her husband, then marry Smith. But none of these women did so; some of them stayed with their ‘first husbands’ until death. In the case of Zina Huntington Jacobs and Henry Jacobs—often used as an example of Smith Marrying a woman whose marriage was unhappy—the Mormon leader married her just seven months after she married Jacobs and then she stayed for years after Smith’s death. Then the separation was forced when Brigham Young (who had married Zina polyandrously in the Nauvoo temple) sent Jacobs on a mission to England and began living with Zina himself” (Todd Compton, In Sacred Loneliness [Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997], 15–16).

[9] Blaire Ostler, “Sexuality and Procreation,” personal blog, Feb. 22, 2016; Blaire Ostler, “Queer Mormon and Transhuman: Part I,” personal blog, Dec. 8, 2016; Blaire Ostler, “Queer Mormon and Transhuman: Part I,” personal blog, Jan. 26, 2017; Blaire Ostler, “Queer Mormon and Transhuman: Part I,” personal blog, Aug. 24, 2017.

[post_title] => Queer Polygamy [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 52.1 (Spring 2019): 33–43Ostler addresses the problems with what she terms the “Standard Model of Polygamy.” She discusses how these problems might be resolved if it is put into a new type of model that she terms “Queer Polygamy.” [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => queer-polygamy [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2024-01-28 19:51:55 [post_modified_gmt] => 2024-01-28 19:51:55 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=23346 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Scared Sacred: How the Horrifying Story of Joseph Smith’s Polygamy Can Help Save Us

Stephen Carter

Dialogue 49.3 (Fall 2016): 75–88

Probably the most destabilizing piece of historical information most Mormons come across is Joseph Smith’s polygamy.

Probably the most destabilizing piece of historical information most Mormons come across is Joseph Smith’s polygamy. Though his practice is vaguely known by many, there seems to come a time when the details really come into focus: when we understand how young some of the girls Joseph took to wife were, how many of the women were already married to his friends, how coercive he could be in gaining a woman’s hand, how he kept Emma in the dark for such a long time, how much pain and heartbreak the practice caused. And it is very difficult to reconcile these details with our desire to revere Joseph Smith as a prophet and as a good man.

This reaction is understandable since so many of us come from cultures that don’t have a history of polygamy. It goes against our tradition of the “one and only,” of the nuclear family, of our hope for equality between the sexes, of our desire to protect children, of our belief in agency. Seriously, would we countenance any of Joseph Smith’s polygamous behavior today? Anyone who would pursue fourteen-year-old girls, or woo already-married women would be lucky to stay out of jail. And certainly that person would be excommunicated.

However, Joseph Smith is not going away. He founded our church, and the Church is committed to defending him, as was shown in the polygamy essay on lds.org that absolved him of his behavior by saying that he was forced into it by an angel with a flaming sword.

The story of Joseph’s polygamy is a disturbing one, but my thesis is that it is also one of the most essential stories Mormonism has—a modern-day version of the story of Abraham and Isaac: a story uniquely capable of shocking Latter-day Saints—not out of the Church, but into a deeper relationship with the divine.

***

The story of Abraham and Isaac is one of the Bible’s most frequently told stories. God commands Abraham to sacrifice his only son on a mountaintop. So Abraham takes Isaac on a long journey and binds him to a boulder. He raises his knife but is stopped by an angel who offers a ram in Isaac’s stead. We have all heard interpretations of this story in church. In fact, it seems to me that we spend much more time on the interpretations than we do on the story itself, probably because, deep down, we feel how horrifying and repugnant the story is to our most basic values. Think about it. A man brought his child to a mountain in order to kill him. Period.

As the Christian philosopher Søren Kierkegaard observed, if you taught the story of Abraham and Isaac in church on Sunday and then on Monday came upon a member of your congregation taking his son to a mountain in order to sacrifice him, what would you do? You would stop him, of course.[1] Using any force necessary. Why? Because killing children is wrong. Period. Further, if you had encountered Abraham on the road with Isaac and understood what Abraham intended to do, what would your reaction be? You would stop him, of course. Using any force necessary. Who cares if an angel was planning to abort the sacrifice at the last second? Who cares if Isaac’s sacrifice is a prefiguration of Jesus’ crucifixion? One does not attempt to kill children. Period.

Given the fact that one should not kill children (period), how can we encounter the story of Abraham’s attempted sacrifice of Isaac? First, we need to go past the story’s events and peer into its inner workings. We need to recognize what the story is doing rather than getting hung up on what it is telling. This is very difficult: it goes against all our training on how to encounter a story.

In some ways, stories are tools. We use them to give order to our experiences. They can be templates that guide our own lives and actions. For example, perhaps we might hear the story of the Good Samaritan and decide to follow the example of the Samaritan by being more compassionate. Perhaps in our youth we are inspired by a testimony given in sacrament meeting, and then, years later, find ourselves testifying of the same thing. When we find a story that resonates with us, we often use it like a cookie cutter, pressing it onto our lives, watching how it molds the once amorphous lump of our experience into a recognizable shape. This reveals a far more profound way that stories affect us. We think that we tell stories, but more often stories tell us. This is a strange thing to contemplate; after all, don’t stories come out of our mouths, through our pens, or through our keyboards?

The science fiction/fantasy novelist Terry Pratchett once described stories as rivers, flowing through space-time.

Stories etch grooves deep enough for people to follow in the same way that water follows certain paths down a mountainside. And every time fresh actors tread the path of the story, the groove runs deeper.

[. . .]

So a thousand heroes have stolen fire from the gods. A thousand wolves have eaten grandmother, a thousand princesses have been kissed. A million unknowing actors have moved, unknowing, through the pathways of story.

[. . .]

Stories don’t care who takes part in them. All that matters is that the story gets told, that the story repeats.[2]

I’m a good case in point. I grew up hearing stories about some of my progenitors who had made their careers as writers, editors, and poets. I decided that I wanted to be a writer as well. So I focused my energies: I joined the student newspaper. I became a full-time news reporter. I got an MFA. I wrote articles, essays, and books, and eventually became a magazine editor. The writer story “told” me, just as it had told my great uncle Paul and great aunt May. Certainly their individual stories had different details than mine because of the time and place they lived in, but we have a very similar overall story. And we deliberately let that story tell us—even invited it. Letting a story “tell” you isn’t necessarily a bad thing: people with knowledge of their family history tend to be more resilient because they have stories close at hand that they can hitch rides on. “Uncle so-and-so was an engineer; I might have an aptitude for that, too. Grandma was a great organizer; I might do well in business.” So, though the first (and usually only) thing we see about stories are the events they narrate, their true power lies in what they do—which can often be invisible. Let’s take a look at the story of Abraham and Isaac again, but instead of focusing on its content, let’s focus on what it’s doing.

***

According to Kierkegaard, the story of Abraham and Isaac is deliberately structured to horrify us. It is trying to break us out of our perceptions of what it means to have a relationship with God. Most of us consider God to be a fatherly figure that blesses us when we are righteous and allows punishment to come upon us when we sin. Mormonism sticks very close to the father metaphor, making God the father of our spirits, a father who presented a plan of salvation for his “children,” who watches over us on Earth as a father might, who wants us to return to live with him. It’s an easily understood and comforting metaphor.

However, Kierkegaard argues that this approach eventually blocks us from being able to enter into a deeper, more direct relationship with God, simply because (as both Christian and Mormon scripture argue) God is beyond our comprehension. As God self-describes in the Book of Moses, “Endless is my name; for I am without beginning of days or end of years” (Moses 1:3). When Moses encounters God, his physical being has to be transfigured in order for him to even survive: “. . . no man can behold all my glory, and afterwards remain the flesh on the earth,” God explains (Moses 1:5). Indeed, when the glory of God leaves Moses, his physical body collapses for hours, and Moses muses that “man is nothing, which thing I had never supposed” (Moses 1:10). When Satan comes to tempt him, Moses sees through him easily simply because Satan is comprehensible to his mortal mind, “where is thy glory that I should worship thee?” Moses asks. “I can look upon thee in the natural man” (Moses 1:13–14).

If Moses, one of the greatest prophets, had never supposed humanity’s utter nothingness compared to God, what makes us think we have even a whisper of understanding concerning the divine? Our mortal minds and weak language can’t even begin to conceive of or attempt to describe God. God is too vast, too powerful, too ineffable, too complex, too simple, too everything. When we approach God, we are stepping into unexplored territory, the one-millionth part of which we’ll never be able to traverse, much less comprehend, much less communicate. What makes us think that a deep relationship with God is epitomized by warm feelings, answered prayers, and a happy life? We are like people living on a sandbar, never even imagining that a continent lies just yards away.

The story of Abraham and Isaac attempts to break us out of our tiny perception by saying something utterly horrifying. “A man of God tried to sacrifice his son.” That sentence should not exist. How can a man of God contemplate the murder of his child? If we are being honest—if we are not letting our awe of scripture and tradition make us lazy—this is where our perceptions explode. This is where we can start to understand that the story is trying to do something normal stories don’t usually do: push us out of itself and into the realm of metaphor. This story is not valuable as a description of a literal occurrence; it’s valuable as a story that brings us into an alternate reality teeming with symbols—like saying, “Once upon a time, a woodcutter brought his son and daughter out into the forest and abandoned them there.” The story of Abraham and Isaac is trying to show us what happens when a person becomes deeply connected with God: when a person has stepped off the sandbar and made for the continent; when a person has gone beyond the father/child metaphor; when a person enters what Kierkegaard called a “subjective” relationship with God.

In order to enter a subjective relationship with God, we need to become a subject ourselves: someone fully aware, fully in control, fully oneself, tapped into the deepest roots of our own unique spark. And then we need to bring that wholeness into a relationship with God, holding nothing back. We are a subject, and God is a subject. There is no subject and object. One does not act while the other is acted upon. We become like Nephi, to whom God granted any desire, not because Nephi had become an excellent sock puppet, but because Nephi knew Nephi, Nephi knew God, and God knew Nephi. They had become one.

When one has entered such a state, conventional morality, which had before taken up so much of our bandwidth, falls away. Not because we should no longer live by it, but because it has become miniscule: irrelevant to our relationship with this amazing being. It was helpful as we groped toward God, but now it’s like sounding out the letters of a word when we know how to speed-read. As the Waterboys once sang, “That was the river. This is the sea.”

When you enter into a subjective relationship with God, the relationship is between you and God only. No one looking at that relationship from the outside has any basis for judging it. The possibilities that this relationship has opened up are so far beyond human understanding that an outside viewer would have no way of perceiving what was happening anyway. That person would have to enter his or her own subjective relationship with God to get even an inkling, and then he or she would be too caught up in his or her own divine relationship to care anymore.

This is what Abraham’s story is pointing us toward: how, when we enter into an intimate relationship with God, we are catapulted beyond good and evil, how human law and rationality suddenly look like pitiful candles in the noonday sun. How we make a quantum leap into a relationship that no eye hath seen nor ear heard nor mind conceived.

At this point, you would be fully justified in saying, with no attempt to hide your incredulity, “You mean that the story of Abraham uses attempted infanticide to symbolize what happens to a person when he or she enters a relationship with God? That’s messed up.” On one level, I completely agree with you. Using a violent, repulsive act to signify a subjective relationship with God seems very strange, especially if, as many faith traditions maintain, God is love.

But I’m hard pressed to think of an approach that would work better simply because of how stories work. As the narrative theorist Robert McKee has pointed out, conflict is the only thing that can drive a story. If things just get better and better for a character, the character has no reason to strive, no reason to struggle; he or she becomes complacent. If the character is nice to the world and the world is nice back, nothing changes. However, the higher the obstacles mount against a character, the more a character struggles, the more he or she suffers, the more intrigued we get, the more invested we become. Conflict arouses our faculties. Niceness lulls us into complacency.

A good example of this principle is Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Everyone and their dog are fascinated with its first book, The Inferno. (Some have even read it.) We hang on every word of Dante’s journey through the nine circles of hell and the torments he observes in each. But less than one percent of those who have encountered The Inferno know a single thing about Purgatorio and Paradiso. Why? Because those two books are full of angels, clouds, and songs. Things just get nicer and nicer—the antithesis of a compelling narrative. So even though our first hope is that a story that could break us out of our complacent relationship with God would be a nice one, it probably can’t be so. Only conflict can awaken us. There must needs be opposition in all things.

To recap. The story of Abraham and Isaac is a horrifying one. None of us here endorse Abraham’s actions in any way. We would all do our level best to stop him from going up that mountain and would probably vote for locking him away. However, this story is not about its content. It is structured to break us out of conventional thought, much as a koan is meant to (e.g., If you meet the Buddha, kill him). It is meant to help us see that a subjective relationship with God is so far outside mortal ken that it cannot be perceived—and especially not judged—from the outside.

***

It seems to me that the tale of Joseph Smith’s polygamy functions as a modern-day Abraham and Isaac story. So many of its events are horrifying; and a man of God commits them. If we caught Joseph Smith on the road to convince a fourteen-year-old girl to marry him, we would do everything in our power to stop him. We would probably even vote to lock him away. Just as with Abraham’s story, the shockingness of the tale wants to eject us from the narrative all together, which is why so few Mormons can stay for long in Joseph’s story without jumping to one conclusion or another: Joseph was forced into polygamy by an angel and is therefore blameless (Abraham was commanded by God to kill his son and is therefore blameless), or Joseph was an oversexed, manipulative, power-drunk man (Abraham suffered from a psychosis; he believed God was speaking to him when it was really his mental illness). If we resist using either of these very understandable escape hatches, I think we can find something of the power of this story.

As with Abraham’s, Joseph’s story is of a man who has entered into a subjective relationship with God and therefore finds himself beyond conventional morality. Abraham was given license to kill. Joseph was given license to marry. But we can’t get caught in the content; in a story like this, it’s all about the symbolism. When one is in a subjective relationship with God, conventional morality is like sounding out letters when one can speed-read. You’ve entered a context where the mortal mind and all its structures are far transcended. God is much too big to be confined to neurons and language. That was the river; this is the sea. The story of Joseph Smith’s polygamy is another version of the story of Abraham and Isaac. They are similarly structured, and they teach the same principle.

Now is the perfect time to say, “But, Stephen, isn’t it obvious that Abraham’s story is a myth while Joseph Smith’s is historical? Actual people were involved in Joseph’s actions. We have records of his doings. How can it be profitable to read his story symbolically when it is painfully literal?” In many ways, I think you’re right. Joseph’s story is thousands of years closer to us than Abraham’s and it takes place in a cultural context similar to our own. Some of it may have happened to our own ancestors. Some of us may feel the reverberations of Joseph’s actions in our own families.

However, I think the story’s proximity is also its strength. As I’ve said, the story of Abraham and Isaac has been repeated so many times that it has lost much of its shock value. (We tell it to children, for Pete’s sake.) And with the loss of that shock comes a diluting of the story’s potency. However, Joseph Smith’s story still hits the gut. We see our own fathers, sisters, wives, husbands, mothers, and brothers in the story. We especially see ourselves. Here is the man we revere as the greatest of all prophets. What would have happened had he approached us? And how do we reconcile our reaction to our respect for prophethood? How do we reconcile our reaction with our own selfhood? Our own subjectivity? We are put in a position of deep conflict, which is where struggle and purification occur. Where a subject begins to get built.

I also think that Joseph’s tale has a somewhat more constructive arc than Abraham’s does. While Abraham’s trajectory leads toward death, Joseph’s leads toward life. Joseph wasn’t commanded to kill; he was commanded to unite—and, implicitly, to multiply and replenish. His unlawful actions tended toward the creation of life, though they also led toward the destruction of many family relationships. His tale’s tendency toward life seems almost like we’re getting our wish that the story of a subjective relationship with God be a less violent one. Joseph breaks foundational social rules, many hearts, and many relationships, but it is because he is uniting while Abraham was destroying. We aren’t headed toward a sacrificial altar; we’re headed toward (let’s not mince words or metaphors) a marriage bed.

Joseph’s story is also more compelling because he actually does the deed. Abraham is stopped before he commits the sacrifice. But Joseph is not. An angel does not step out at the last moment to halt the nuptials. In fact, he seems to be standing behind the couple, wielding a flaming sword (the closest thing an angel has to a shotgun). Abraham gets to go home with a living son, and Joseph gets to go home with a new wife, but also with the hordes of problems that would plague him (and his people) for the rest of his short life.

Joseph’s story seems more honest to me. The person who comes into the most intimate relationship with God isn’t necessarily the person who is happy and prosperous. We need only consider the story of Jesus to understand that. That’s where Joseph’s story finally transcends Abraham’s. Joseph made the “sacrifice.” And the consequences followed. What is it to be in a subjective relationship with God? You find yourself beyond good and evil. You find yourself in a relationship with a being so great, so incomprehensible that no one outside the relationship can understand or judge it. That is its beauty. It is only you and God: an ultimate connection with everything that was, is, and will be. Including everything and everyone. You are not separate. You are one. You are not gone from existence, life, or relationship: you have become sealed to it all. But that is also its danger. The only thing you’re guaranteed from your intimate relationship with God is an intimate relationship with God. Prophets die, sometimes horribly. But if you have that relationship, that’s all you need.

At this point, it is tremendously hard not to go back to the content of Joseph Smith’s polygamy story. It’s hard not to say, “Hold on, you’re saying that Joseph Smith’s subjective relationship with God nullifies all the pain and destruction he caused? All you have to do is say, ‘God told me to do it,’ and you’re off the hook? Are you saying that Joseph Smith had an intimate relationship with God while he was ruining the intimate relationships of so many other people?”

These are totally legitimate questions if the content of the story matters. But in this context, the content matters only insofar as it serves to eject us from the story. Once it has done its job, the content drops off like the booster rocket from a space shuttle. Joseph’s actions propelled us out of the narrative, and now we must leave them in order to explore our own possibilities in the divine.

Yes. If we met Joseph on the road to take a fourteen-year-old wife, we would do all in our power to stop him. The pain resulting from the way he practiced polygamy is real. It will never stop being real. I’m not trying to justify him in any way. I am not arguing that he was allowed to do what he did because he was in a subjective relationship with God. I am talking only about how these two stories work. How they symbolize aspects of an intimate relationship with God. The stories are confusing when their content takes the spotlight, when we don’t see them as pointing to concepts that are galactically foreign to our experience and assumptions. “Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him” (1 Corinthians 2:9).

Probably the most compelling thing about Joseph’s theology is his insistence on our radical agency. The agency of a human soul is so complete, so utter, that one-third of God’s children could choose Satan over Jehovah while in the presence of God (Abraham 3:28). We are the irrevocable creators of our souls. We forge ourselves choice by choice. There is no limit to the heights we can reach or the abysses we can plumb. We can become gods: beings that have penetrated every secret, connected with every soul, experienced every atom. But we are almost always trapped inside nice stories that preach nice morals and bring us to nice endings. But these stories stop significantly short of revealing our potential. We are like people who have never seen the Milky Way because the city lights tower above us. These lights make us think we know the way. They show us paths to known destinations. But that is not what Joseph’s theology was about. That is not what Jesus was trying to teach. Sell everything you have, they said. Leave your family. Let the dead bury their dead. Pluck out your eye. (Each a horrifying metaphor.) Stop at nothing to reach that god-spark inside of you.

***

Both of the stories I’ve talked about have been about men. But there are similarly structured stories involving women. For example, Laura Brown’s character in Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours (or its luminous film adaptation). And just to let you know: spoiler alert. Laura Brown is a 1950s housewife with a doting husband, a new suburban home in southern California, a beautiful (though intense) little son, and a daughter on the way. But it is evident from the very beginning that Laura is burdened by some malaise, one that becomes so onerous she comes very close to killing herself. But at the end of the movie, we find out that a few months after giving birth, Laura had boarded a bus and gone to Canada, never seeing her family again.

Laura Brown’s abandonment of her family is unthinkable to me. “Monstrous,” as one character put it. Her actions are so far removed from my experience and thoughts that I cannot imagine what would motivate her to do such a thing. And the story never gives me any help. I’ve watched the movie at least half a dozen times and have found only one hint as to what might have motivated Laura Brown. At the end of the movie, a much older Laura tells another character, “I had a choice between life and death. I chose life.” No particulars, no details, no back-story. We just have to take her word for it. For a long time, I felt that this was a weakness in the story, but now I see it as a strength.

Abraham’s story is the same: he has a doting wife, a tent in the sunny desert, and a beautiful son. But he is weighed down by a burden so onerous that he comes very close to killing his son. Why does he try to perform such a monstrous act? The story gives us only one hint: because God commanded it (without giving a reason why). Abraham had to choose between obeying and disobeying the life force of the universe. And he chose to obey it. But he gives us no particulars, no details, no backstory. We just have to take Abraham’s word for it. Joseph had to take more wives. Why? Because he was commanded to by an angel with a flaming sword. These stories all have the same structure. My reaction to Abraham’s story is the same as my reaction to Laura Brown’s and Joseph Smith’s. It’s unthinkable. But as we have seen, there are many unthinkables strewn throughout the scriptures.

Is it worth sacrificing money to become one with life? Is it worth sacrificing a job, a boat, a car, social status? These stories careen past those banal questions without even a glance. They take us right to the edge of the cliff and push us off. How great is the worth of one soul? So great that Laura Brown left her young family to bring hers into the light. So great that Abraham made his only son into a sacrifice. So great that Joseph Smith broke hundreds of hearts.

Those who have ears, let them hear past these monstrous metaphors and into their structures.

Jesus did not teach the parable of the person who put off becoming one with God until the next life. He did not praise the rich or the successful or the powerful. He didn’t even teach kindness or tithing or humility or the Word of Wisdom or modest dress codes: he taught atonement. Becoming one with God: something beyond the grasp of every human mind. Something no one has ever been able to capture in any art. Something we can only ever point toward.

In many ways, what “happens” in a story is secondary. Its content is beside the point. What the story does is the most powerful thing about it. Most stories want to tell us. But there are a few that are structured in such a way that they try to violently eject us from themselves and let us see a symbol of a connection with the indescribable Divine. To let us feel for a moment an inkling of what it’s like to be connected with God. The same God who—so long ago, so recently, still—wades deep into matter unorganized and brings forth a brand new story.

[1] Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, translated by Alistair Hannay (New York: Penguin, 1985), 59.

[2] Terry Pratchet, Witches Abroad: A Novel of Discworld (New York: Harper, 1991), 3.

[post_title] => Scared Sacred: How the Horrifying Story of Joseph Smith’s Polygamy Can Help Save Us [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 49.3 (Fall 2016): 75–88Probably the most destabilizing piece of historical information most Mormons come across is Joseph Smith’s polygamy. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => scared-sacred-how-the-horrifying-story-of-joseph-smiths-polygamy-can-help-save-us [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2024-01-28 18:53:53 [post_modified_gmt] => 2024-01-28 18:53:53 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=18937 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

“The Highest Class of Adulterers and Whoremongers”: Plural Marriage, the Church of Jesus Christ (Cutlerite), and the Construction of Memory

Christopher James Blythe

Dialogue 46.2 (Spring 2016): 1–39

Blythe shows the denial among Culterites followers that the founder was involved in plural marriage.

“Anyone who says Father Cutler ever sanctioned, upheld, or practiced polygamy are ignorant, unlearned, dishonest, or deceived, for they took false reports for facts, not knowing the truth.”[1][2]

The Mormon polygamous passage was not traversed solely by those who sided with Brigham Young. Plural marriage was part of the legacy handed down from the Nauvoo experience and as Joseph Smith III once stated, “nearly all of the factions into which the church broke had plural marriage in some form.”[3] There were certainly exceptions to this rule—Sidney Rigdon and Charles B. Thompson, for example, never practiced plural marriage. However, polygamy and questions about its origins and extent could not easily be ignored by any of the sects.

In fact, polygamy served and continues to serve as a means by which one variant of Mormonism positions itself against another. Although some of those who would become members of the Church of Jesus Christ (Cutlerite) were involved in the plural marriage experience in Illinois and Iowa, by the time of its official inception in 1853, the church had rejected the practice. This article traces the evolving memory of and public reaction to plural marriage among the Cutlerites in an effort to understand how a religious movement conceptualizes and re-conceptualizes its past in order to solidify its identity in the present.

Studies of memory—that is, how a community remembers and represents its own past—have already proved useful to scholars seeking to understand Mormon culture. Both Kathleen Flake and Stephen C. Taysom have demonstrated how the LDS Church has “forgotten” its polygamous passage via emphasizing other distinctive historical moments (e.g., Flake’s argument concerning the first vision)[4] or whitewashing these events in Mormon popular histories (e.g. Taysom’s discussion of Gerald N. Lund’s The Work and the Glory series).[5] A similar approach also informed David Howlett’s compelling study of how the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as the Community of Christ) came to remember the practice of polygamy, as their cousins came to forget it.[6]

As these scholars have already emphasized, memory is a crucial component of how institutions define themselves and police their borders. The particular lens through which a group chooses to see its past shapes its members’ understanding of who they are in the present. As David Lowenthal has stated, “the past as we know it is partly a product of the present; we continually reshape memory, rewrite history, refashion relics.”[7] “History” as we are using it here refers to the crafting of the past via available source materials. Neither the process of constructing memory nor the writing of history is unbiased, but the latter is “based on empirical sources which we can decide to reject for other versions of the past,” whereas the former is shaped more by the present requirements of the community’s self-definition.[8]

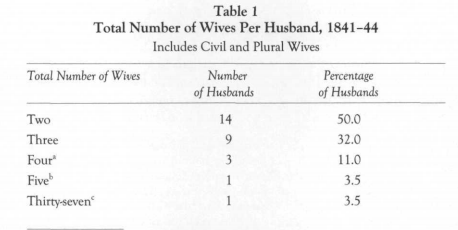

This article is divided into two major parts. The first section is devoted to a history of the proto-Cutlerite—that is, the movement as it existed as a colony before organization as a church—involvement with polygamy. Here we will count wives and husbands and measure the extent of overall knowledge of polygamy during the period. The second section is devoted to a history of the Cutlerite—that is, the movement after the official founding date of the Church of Jesus Christ—memory or representation of polygamy.

The history of Cutlerite understandings of polygamy—their memory of Mormonism’s polygamous past—can be divided into three major periods. The first period, between 1853 and 1864, was characterized by a collective and institutionally enforced silence, which attempted to mute those voices who knew of polygamy’s past. During this period, the Cutlerites were haunted by the memory of polygamy, even when (or perhaps, particularly because) it was unacknowledged in public. As we will see, there were unavoidable reminders of a polygamous past in their midst.

A second period was initiated at Alpheus Cutler’s death and brought on by the growing intensity of RLDS missionary work that closely equated the community with their apparently unfortunate past. Gone was the policy of silence on polygamy altogether. A new strategy emerged in its place, one in which the church openly denied and distanced itself from any involvement in past polygamy. As we will see, such public denials hid residual private anxieties in the second generation. Regardless, it was during this period that the community’s collective aversion to polygamy led the Cutlerites to form their own identity—by pushing against the Brighamites, with their corrupt marital practices, while simultaneously seeking to respond to the insinuations made by RLDS missionaries, former Cutlerites, and neighboring non-Mormon communities.

A third period began with the twentieth-century arrival of Cutlerites to Independence, Missouri. In their new environment, where they were surrounded by a variety of Mormon sects, identity formation became all the more important. Likewise, the twentieth century presented new contradictions to the Cutlerites’ narrative of plural marriage from another source: professional historians. Scholars published en masse concerning Joseph Smith’s many plural marriages; later in the century, they even turned their attention to Alpheus Cutler. The Cutlerites responded in the form of official church histories and even found allies in other movements’ apologetic histories. In effect they moved from doing memory, presenting the past from their personal knowledge, to the claim that they could construct the past from historical documents. Likewise during this period, the effort to construct identity by pushing against the Brighamites was intensified and as a result, Brigham Young and other historical Mormon figures began to appear as stock villains. The history of the Church of Jesus Christ offers us a view of how one denomination has tried both to preserve and to construct a heritage rooted in the past—a heritage which has shifted and been re-imagined over the course of its history.

A Twenty-First Century Encounter

On June 4, 2002, I held my first and only interview with Stan ley Whiting, president of the Melchizedek Priesthood of the Church of Jesus Christ. Like many students of Mormonism, I stumbled across the church in the writings of Danny Jorgensen and D. Michael Quinn and wanted to know something about this small group of believers who claimed to have maintained the Mormons of Nauvoo intact into the twenty-first century. As I sat in the Whitings’ living room in Blue Springs, Missouri, I found something very tender in the elderly gentleman, who would periodically remark that I looked just like his grandson. We spoke for several hours as he bore testimony of the Restoration in general and the history of the Cutlerites in particular. He had recently traveled to visit the rebuilt Nauvoo Temple, before it was dedicated, and kindly expressed the similarities of our faiths, especially the fact that both communities maintained what he referred to as “the upper room work” or simply “the priesthood.”

We had only spoken a few minutes, when he looked at me, smiled, and said, “Now I’m picking on you now and I don’t want you to take this personal, but you belong to the Utah [Church] . . . to us, one of the grossest sins in the world is polygamy.” He went on to express his irritation with scholars who had persistently tried to “destroy our integrity” in reference to whether Alpheus Cutler and the early Cutlerites were polygamists or not. He continued, “And we have got proof in our records that we don’t show to people what happened clear back through Alpheus Cutler. Alpheus Cutler was claimed by the church—your church—as having twenty-seven wives, eighteen wives.” He raised his hands, exasperated. “I don’t pay any attention to that. He only had one wife and that’s Lois.”[9]

Six years later, when I finally presented some of my research on the Cutlerites at a conference of the John Whitmer Historical Association, I remembered Whiting’s concerns and for that reason decided to avoid any mention of polygamy at all. Instead, I was excited to probe the singular ecclesiology of the faith. However, by the end of the session, I was reminded of the interest and controversy in questions concerning the Cutlerite involvement in plural marriage. After finishing the public Q&A, I was approached by several scholars who wanted to discuss the topic. One senior scholar, who had inadvertently offended a Cutlerite a year previously, simply asked if I felt it was accurate to say that Cutler practiced polygamy. Another asked in hushed tones whether the records mentioned anything about their plural marriages. When I answered in the negative, he commented that the records were probably doctored or the important portions left unavailable; otherwise, he speculated, we would find the information “we all” suspected was there.

Despite the guaranteed interest in such a project, I had decided I would leave the subject of plural marriage for someone else to unravel. I wanted to avoid the controversy. Yet, as I continued my research, I came to think that the Cutlerites’ experience and reaction to polygamy was and remains a crucial part of their story. Specifically, I began to look for a way that would allow me to tell the story of Cutlerite polygamy in a historically accurate way—drawing on all of the available source material, while being responsible as a scholar to both my subject and my audience, and even sympathetic to the Cutlerite plight.

Ultimately scholars still do not have access either to those hypothetical documents that Stan Whiting claimed would exonerate Cutler from the allegations leveled against him or to those that the above-mentioned historian suggested would add even further exciting details of polygamy’s heyday. Yet the records we do have paint a more complicated and compelling portrait of the movement than we could gain from being able to add to or subtract wives from the story. Instead, the history of Cutlerism’s reaction to polygamy is one of coping with a memory silenced, repressed, and deliberately forgotten, but ultimately important to the Cutlerite construction of identity.

The History of the Cutlerites and the Cutlerlites in Mormon History

Alpheus Cutler, a Latter-day Saint since 1833, grew to prominence in Nauvoo as a member of the city’s High Council, one of the temple committee, and the temple’s “master builder.” As a confidant of Joseph Smith, Cutler was entrusted with Nauvoo’s emerging esoteric theology. On October 12, 1843, he was initiated as a member of the Holy Order (also known as the Anointed Quorum), through what would come to be known as the temple endowment. On November 15, 1843, he was sealed to his wife, Lois, and subsequently the couple received the ceremony referred to as the “fullness of the Melchizedek Priesthood.” Although he was not one of the original members of the Holy Order endowed in 1842, he was only the sixth man to receive this capstone anointing, one week before the first of the twelve apostles, Brigham Young, received the rite.

On March 11, 1844, Alpheus Cutler was chosen as one of the charter members of the Kingdom of God, frequently referred to as the Council of Fifty, a religiopolitical society designed to promote the Saints’ political interests, including interactions with governments, Joseph Smith’s candidacy for the presidency of the United States, and colonization efforts. The Kingdom was tied to Mormon millenarian expectations and was intended to function as a worldwide government during the millennial reign of Christ. One responsibility associated with the Council of Fifty was the effort to bring the Mormon gospel to the Native Americans. During this period, Cutler received an assignment to conduct such a mission in Kansas.[10]

As a member of the High Council, Cutler played a key role in supporting the leadership of the twelve apostles following Smith’s death. This support included participating in the excommunication of supporters of rival movements.[11] He also served in the temple, administering the ceremonies of the Holy Order to the rest of the Latter-day Saints. Once the westward migration began, Cutler served as the president of the Municipal High Council in the settlement of Winter Quarters. By the end of 1847, he was eager to fulfill the assignment he had previously received as a member of the Council of Fifty. With Brigham Young’s support, he established a mission to the Native Americans, and in the following months relocated to Silver Creek, Iowa, where he served as the branch president.[12]

The period from the undertaking of this mission to the official founding of the Cutlerite church in 1853 could be termed the Proto-Cutlerite period, in which those who accompanied Cutler on his mission began to see themselves as distinct from the rest of Mormonism. In time, the separation between those who accompanied Cutler, with their focus placed on converting the Native Americans, and other Mormons, who were focused on the trek west, led to increasing tensions between the two communities. By the time Young had re-established the first presidency and planned for the colonization of the Great Basin, the proto Cutlerites had begun to see messianic possibilities for their movement in general and for their leader, Alpheus Cutler, in particular. They saw themselves as responsible for building relationships with the Native Americans—relationships that would result in the re-establishment of the Saints in Missouri. Though the rift had its origins in what Richard Bennett has referred to as “difference over place and priorities,” in time it blossomed to encompass competing mental worlds of Mormonism’s future.[13]

Lamanism, as Mormons in the surrounding area termed the proto-Cutlerites’ message, was seen as a heretical threat to the Church. Following a series of investigative trials with the regional High Council directed by the apostle Orson Hyde, the official sanction for the Native American mission was withdrawn. Many of those who were active in the mission were excommunicated; eventually, on April 20, 1851, Alpheus Cutler was excommunicated as well.[14] Not long thereafter, the proto-Cutlerites abandoned their missionary efforts due to a lack of conversions and overwhelming hardship.[15]

In 1852, the colony relocated to southwest Iowa, where they founded the town of Manti. On September 19, 1853, Alpheus Cutler announced that he had had a revelation to re-organize the Church of Jesus Christ.[16] Beginning on that date, his followers were re-baptized and a new church leadership body was selected. The community prospered, numbering a few hundred at its height. In the late 1850s, the Cutlerites attracted the attention of another movement founded only a few months before their own: the “new organization,” later known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The evangelistic group quickly depleted a large chunk of the Cutlerites’ membership.[17] With pressures from the encroachment of RLDS ministers and the death of Alpheus Cutler in 1864, the Cutlerites decided once again to relocate, this time to Minnesota, where they founded the town of Clitherall.

The Cutlerites struggled at the end of the nineteenth century, especially following their renewed encounter with Josephite missionaries, to the point that the church rarely held meetings. With the death of Chauncy Whiting in 1902, there was an eight-year hiatus of any meetings of the organization until Isaac Whiting, his successor, accepted his position. For these reasons, there is a fourteen-year gap in the organization’s minutes before they begin again with a notice that the church “started anew in 1910.”[18] Few of the first generation of Cutlerites remained to assist in this renewal.

In 1930, a group of Cutlerites relocated to Independence, Missouri, an action which inadvertently resulted in schism. Although the Cutlerites were divided between two rival churches for some time, one in Minnesota and one in Missouri, the only surviving community by the 1950s was in Independence, where the church currently resides. For the past hundred years, the community has never been more than a handful of believers, often on the verge of extinction.

The Cutlerites attract a unique degree of interest from scholars and armchair historians compared to the other churches of the Restoration. Among the most compelling components of the Church of Jesus Christ is its connection with Nauvoo esotericism. After all, Cutler’s claim stemmed from secret commissions received as part of the Council of Fifty and the Anointed Quorum, his reception of the Second Anointing, and most importantly, the perpetuation of the Nauvoo-era endowment into the present. Mormons of various factions have fantasized that the Cutlerites exist in a timeless state, unchanged since Nauvoo. Some wonder what the ceremonies performed on the second floor of their meeting house encompass, and if knowledge of them would demonstrate what the twelve apostles of the LDS Church must have changed since Nauvoo. For example, one writer has noted that the Cutlerites’ ceremony was evidence that Masonic elements were additions made by the Brighamites—regardless of the fact that he had no access to details of the Cutlerite ceremony.[19] Although the trope of Cutlerites as the keepers of Nauvoo esotericism is what undoubtedly piques our communal curiosities into the smallest remaining nineteenth-century sect, there is no reason to question whether the Church of Jesus Christ has somehow escaped the impact of time and space.[20] The history of all known institutions includes change over time.

Our historical curiosity also has something to do with our tendency to position the Church of Jesus Christ on a constructed spectrum of the Restoration. We are used to thinking of the LDS Church as the proponents of Nauvoo Mormonism with its emphasis on temple rites and, historically, plural marriage, on one side of the spectrum, and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, who vehemently opposed polygamy, on the other. We have come to popularly think and speak of the Cutlerites as existing in a space somewhere between these two poles, part LDS since they maintain Nauvoo esotericism, and part RLDS in that they reject plural marriage. There are two problems with this comparative methodology employed to understand the Cutlerites: first, this spectrum is much too simplistic; second, it tries to come to terms with the Cutlerites through analogy rather than by examining the tradition on its own merits. Of course, my comments are not designed to discourage our interests in the Church of Jesus Christ, only to encourage us to suspend what we think we know about the community in order to gain a perspective fully positioned in the sources at our disposal.

Polygamy in Nauvoo and Silver Creek (1845–approx. 1851)

Before we can use the Cutlerites as a case study in memory construction, we should look at the historical moment to which the new institution was reacting. The first subject we need to probe is to what extent the available records suggest Cutlerites were involved in plural marriages. Should scholars speak of the proto-Cutlerite period as a polygamous phase in the sect’s history? What knowledge did individual Cutlerites have about plural marriage, in their own sect or among the followers of Brigham Young, prior to Orson Pratt’s 1852 announcement? When exactly Alpheus Cutler was introduced to plural marriage as sponsored by Joseph Smith or other ecclesiastical leaders is uncertain. However, his membership in the Holy Order and Nauvoo’s High Council would have positioned him with plenty of opportunities to learn of the practice. For example, Cutler may have been in attendance when Hyrum Smith read the July 12, 1843, revelation before the Nauvoo High Council on August 12, 1843. Unfortunately, there was no attendance taken during the historic meeting and Cutler was absent the following week.[21] Because the Holy Order was populated with many of those who were involved in early plural marriage, Cutler would have also been able to discover the practice through these associations. That he remained unaware of polygamy until after Joseph Smith’s death seems highly unlikely.

It is certain that by 1845 Cutler had become fully immersed in the world of post-martyrdom plural marriage. His twenty-year-old daughter, Clarissa Cressy Cutler, married the apostle Heber C. Kimball on February 29, 1845. (Cutler’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Emily, also married Kimball, but not until December 1845.) On August 9, 1845, Kimball, in turn, performed the ceremony that sealed Cutler to his first plural wife, the recently divorced ex-wife of Orrin Porter Rockwell, Luana Hart Beebe.[22] On January 14, 1846, following a general policy for those couples that had previously been sealed outside of the temple, Alpheus had his sealing to Luana, as well as his earlier sealing to Lois, performed again within the edifice. The same procedure was followed with the re-performance of Cutler’s higher anointings, although this time with both Lois and Luana accompanying him in the rite.[23] On February 3, 1846, Cutler was sealed to five additional women: Margaret Carr, Abigail Carr, Sally Cox, Disey Caroline McCall, and Henrietta Clarinda Miller.[24] Cutler’s new wives received their anointings on the same day.

Of these seven women, we only have a record of three accompanying him during the Native American mission. Alpheus Cutler had children with only one of his plural wives, Luana. Danny Jorgensen’s research has uncovered three children born to the union between 1846 and 1850 or 1851. In order to conceal their paternity, the two children to survive childhood did not use the last name Cutler. Jacob Lorenzo, a son born in 1846, was given Cutler’s mother’s maiden name, Boyd, and Olive Luana, a daughter born in 1850, used the surnames of Luana’s two later husbands al ternately.[25]

Alpheus Cutler, his wives, and his daughters appear to have been the only actual participants in plural marriage from the group of individuals in Silver Creek who eventually became Cutlerites. However, during the proto-Cutlerite period, there was one other polygamist family connected to the community: F. Walter Cox, one of Cutler’s counselors, and his three wives. Luman H. Calkins, Cutler’s other counselor and the bishop of the Silver Creek Branch, though not technically a polygamist, was also sealed to multiple women in the Nauvoo temple, as he was sealed to both his current and his deceased wife.[26]

Yet as Jorgensen’s research has demonstrated, this was far from the extent of the colony’s polygamous ties. Many of those who would become Cutlerites participated in the Nauvoo Temple experience and began the trek westward to Winter Quarters, where polygamy was becoming an increasingly public affair.[27] Al though Jorgensen may have overstated the situation when he wrote that early Cutlerites possessed an “intimate, detailed directly experiential knowledge” of plural marriage, their associations make it unlikely that many of Cutler’s followers needed Cutler to introduce them to plural marriage, as they would have already learned of the practice either by rumor or by personal experience with the rest of the Brighamites.[28]

Further, there were several Cutlerites with relatives who practiced plural marriage either in Nauvoo or later in Utah. In most cases these were female relations polygamously married to men who continued to accept the leadership of the twelve apostles. There were also at least two additional male polygamists related to the community. Chauncy Whiting, Alpheus Cutler’s eventual successor, was never a polygamist, but his brother Edwin Whiting was sealed to three women in the Nauvoo Temple.[29] One of Edwin’s wives also had ties to the community. Mary Elizabeth Cox Whiting’s brother, Amos Cox, would also become a Cutlerite. In fact, three of Amos’s siblings were polygamists and his own father-in-law had been sealed to eight women in the Nauvoo Temple.[30] Finally, Calvin Beebe, who would act as the branch president of the Farm Creek Branch of Cutlerites, performed plural marriages in the Nauvoo temple.

The proto-Cutlerites were also aware of Alpheus Cutler’s and F. Walter Cox’s practice of plural marriage. As will be shown, Cox made very little effort to conceal his polygamous status. Of course, asserting that all Cutlerites knew about Cutler’s polygamy would be a dangerous assumption. It is possible that knowledge of Cutler’s relationships were only shared with the community’s elites, a practice that would have had a strong precedent in 1840s Nauvoo.

However, it is evident that there were those who knew detailed information about Cutler’s marriages. Iva Gould, a Cutlerite descendant who belonged to the RLDS faith, recorded her experience of probing her parents and grandparents for information concerning polygamy. In an undated (twentieth-century) letter, she wrote:

I asked my folks some of the questions about the Cutlerites that you asked yesterday. They said it was common belief in the early days that Alpheus Cutler had been a polygamist, though the present generation of Cutlerites deny it. My father said that at one time on a short journey he stopped at the home of Mrs. [Luana Beebe] Boyd who told him she was one of the wives of Alpheus Cutler, that she had been a poor girl without relatives to care for her and Cutler told her if she would be sealed to him he would support her.

On reaching home my father asked my grandfather, Francis Lewis Whiting, a brother of Chauncey Whiting, if it was true that Father Cutler had more than one wife. He answered reluctantly, “I suppose it is true that he had three wives.” And when I asked if Mrs. Boyd was one of them, he said, “Yes, I suppose she was.” He was a staunch Cutlerite and did not like to admit it but was too honest to deny it. My grandmother then said that Father Cutler got rid of his wives before he started the church, that he took one of them on a mission to the Indians and she died there. Another he gave away to a man who wanted to marry her.[31]