Community of Christ

Introduction

Within these articles, Dialogue delves into the history, beliefs, and practices of the Community of Christ. The Community of Christ, formerly known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church), traces its origins to Joseph Smith III, the son of Joseph Smith Jr., who founded the LDS Church. It explores the evolution of the RLDS Church into the Community of Christ, as well as its distinctive theological perspectives and organizational structure. Find a wealth of articles from a variety of perspectives, contributing to a well-rounded view of the Community of Christ and its place within the broader landscape of Mormonism.

Mormon Women in the Ministry

Emily Clyde Curtis

Dialogue 53.1 (Spring 2020): 129–142

Interview with Brittany Mangelson who is a full-time minister for Community of Christ. She has a master of arts in religion from Graceland University and works as a social media seeker ministry specialist.

Interview with Brittany Mangelson who is a full-time minister for Community of Christ. She has a master of arts in religion from Graceland University and works as a social media seeker ministry specialist.

[post_title] => Mormon Women in the Ministry [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 53.1 (Spring 2020): 129–142Interview with Brittany Mangelson who is a full-time minister for Community of Christ. She has a master of arts in religion from Graceland University and works as a social media seeker ministry specialist. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => mormon-women-in-the-ministry [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-10-19 01:49:41 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-10-19 01:49:41 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=25888 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

British Latter Day Saint Conscientious Objectors in World War I

Andrew Bolton

Dialogue 51.4 (Winter 2018): 49–76

What of the Latter Day Saint movement that claimed to prophetically discern the times and seasons of these latter days and also boldly proclaimed that they were the restoration church?

What of the Latter Day Saint movement that claimed to prophetically discern the times and seasons of these latter days and also boldly proclaimed that they were the restoration church?

[post_title] => British Latter Day Saint Conscientious Objectors in World War I [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 51.4 (Winter 2018): 49–76What of the Latter Day Saint movement that claimed to prophetically discern the times and seasons of these latter days and also boldly proclaimed that they were the restoration church? [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => british-latter-day-saint-conscientious-objectors-in-world-war-i-2 [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-10-11 20:57:20 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-10-11 20:57:20 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=22908 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Community of Christ: An American Progressive Christianity, with Mormonism as an Option

Chrystal Vanel

Dialogue 50.3 (Fall 2017): 89–115

I thus argue that Mormonism exists wherever there is belief in the Book of Mormon, even though many adherents reject the term “Mormonism” to distance themselves from the LDS Church headquartered in Salt Lake City.

I thus argue that Mormonism exists wherever there is belief in the Book of Mormon, even though many adherents reject the term “Mormonism” to distance themselves from the LDS Church headquartered in Salt Lake City.

[post_title] => Community of Christ: An American Progressive Christianity, with Mormonism as an Option [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 50.3 (Fall 2017): 89–115I thus argue that Mormonism exists wherever there is belief in the Book of Mormon, even though many adherents reject the term “Mormonism” to distance themselves from the LDS Church headquartered in Salt Lake City. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => community-of-christ-an-american-progressive-christianity-with-mormonism-as-an-option [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-10-11 20:58:19 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-10-11 20:58:19 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=19031 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

The Kirtland Temple as a Shared Space: A Conversation with David J. Howlett

Hugo Olaiz

Dialogue 47.1 (Spring 2014): 104–123

An oral interview between an LDS Member and a Community of Christ member regarding the history of the Kirtland Temple. They explain that despite differences in religious beliefs, people can still form friendships and cooperate.

This interview was conducted on July 4, 2013, in Community of Christ’s Kirtland Temple Historic Site Visitor and Spiritual Formation Center, located next to the temple.

A third generation Mormon from La Plata, Argentina, Hugo Olaiz has a degree in Letters from Universidad Nacional de La Plata and a Master’s in Spanish from Brigham Young University. Hugo has published both fiction and scholarly pieces in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, and miscellaneous articles in Sunstone magazine. He recently completed an 11-year stint as news editor for Sunstone and lives with his family in Oxford, Ohio.

David J. Howlett is a visiting assistant professor of religion at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York where he teaches about American religious history. He is the author of Kirtland Temple: The Biography of a Shared Mormon Sacred Space (University of Illinois Press, 2014).

Of all the Mormon historical sites that ended up in the hands of the RLDS Church (today known as the Community of Christ), none is more significant for the LDS Church than the Kirtland Temple. Despite its contrast, both in form and function, with all other LDS temples, the Kirtland Temple is still claimed by the LDS Church as the first temple of this dispensation and the setting of glorious visitations that form a crucial part of Mormon history, ritual, and doctrine. Although the building is not owned by the LDS Church, over 90 percent of visitors are LDS. This means that members of the Community of Christ, acting as hosts and guides, find themselves sharing this space with visitors who may interpret it differently than they do. LDS visitors are sometimes baffled that their church doesn’t own this sacred site, and some are confused by the differences between current LDS temples and their Kirtland precursor, which doesn’t even have a baptismal font.

How is it that the RLDS Church ended up owning the Kirtland Temple?

The ownership goes back to a broken chain of title in the 1830s. Over the course of the 1840s and 1850s, many different Latter Day Saint denominations occupied the Kirtland Temple. By 1862, the Kirtland Temple was auctioned off to settle outstanding debts of the early Church in the area, and it was bought by a man named Russell Huntley for $150. Huntley put a new roof on the temple, he painted it, re-stuccoed it, and re-plastered it. If he hadn’t done that, the temple would have fallen into ruin. By 1874, Huntley had associated himself with the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and he sold the temple to Joseph Smith III for $150—the same price that he had paid in 1862.

Because of the broken chain of title, Joseph Smith III was advised to simply wait until 1883, when Ohio law would grant legal possession after having used a property for twenty years. Joseph Smith III, however, wanted to get the Reorganized Church recognized as the true successor of his father’s church in a court of law. So in February 1880, the Reorganized Church fi led a lawsuit in a small county court over the possession of the temple and named John Taylor as one of the defendants. Of course John Taylor was not going to show up—he was in hiding and never even heard about the case. The RLDS Church got the judge to say almost everything they wanted him to say—that the Reorganized Church was the true church because of its continuation of the original Mormon doctrines, etc. The judge’s statement was published in The Saints Herald—except for the last two sentences, which actually threw out the case!

So for over 100 years RLDS historians in good faith thought of the 1880 lawsuit as the reason why the RLDS Church owned the Kirtland Temple. Then in the early 2000s, Kim Loving, president of the then Kirtland Stake of the Community of Christ, conducted research for his master’s thesis and discovered that the process had been more or less propaganda by Joseph Smith III, and that the lawsuit had been thrown out.[1]

So the real reason the Community of Christ today owns the Kirtland Temple is what is called “adverse possession”: They were here for the longest period of time as the continual possessor of the temple, having a local congregation and meeting in the building.

I’m sure the LDS Church, and possibly other branches of the Latter Day Saint movement, would like to be seen not only as the legitimate successor of Joseph’s church but also as the owner of the Kirtland Temple.

For nineteenth-century Community of Christ members, the Kirt-land Temple legitimized them in their own eyes and, they hoped, in the eyes of other Americans. By the 1880s, there was a sign on the second fl oor of the temple which literally said, “We are not the Mormons.” “We, 30,000 [members of the RLDS Church], are not associated with that Utah group whose doctrines are an abomination to us, working all manner of iniquity,” and went on and on distancing the RLDS Church from Utah Mormons. Then by 1899, the RLDS painted an inscription on the front of the temple that said, “HOUSE OF THE LORD—BUILT BY THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER DAY SAINTS, 1834.” They added: “REORGANIZED CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER DAY SAINTS IN SUCCESSION BY DECISION OF COURT, FEB. 1880.” That same sign stayed on the Kirtland Temple until 1986.

Let’s talk about what the early Reorganized Church did in the Kirtland Temple. What would they use the building for?

They used it a variety of purposes. By the 1880s, there was a congregation that met every Sunday and on Wednesdays for prayer meeting. This went on until 1959. There were also conferences. In 1883, for example, there was a general conference, during the period when the RLDS were holding general conferences once a year. Priesthood conferences were also held at different times, all the way to the present.

Starting at least in the 1910s, continuing into the 1950s, traditional RLDS “reunions” or “family camps” were held on the temple’s property. This is a tradition that LDS don’t have. The origins go back to the 1880s, out of a desire to have general conference twice instead of once a year. These reunions were regional conferences that functioned similarly to a week-long revival: There was preaching, praying, and testifying all day long, with services in the evening. By the early twentieth century, it took on more of a recreational feel. Imagine the Kirtland Temple, by 1911, surrounded by people camping out in tents—that’s the scene you would have seen in the summer. Worship services were held during the day in the temple, and the cooking was done in the yard. Eventually the reunions lost some of their rural feel when showers were built across the street, in a building that is today part of the local congregation.

I like the image of the temple surrounded by tents. Yet I assume the RLDS Church never saw Kirtland as the central place of the church?

It was seen as it was in the 1830s: a stake of Zion, but not as Zion itself or its capital. Kirtland was a center for the people of this particular region, but not the center to which people would be encouraged to gather. The RLDS followed the LDS doctrine of gathering into the 1970s, and for many families even into the 1980s. The RLDS were encouraged to gather in Independence, Missouri, because that was the place for the New Jerusalem.

That meant moving your family to Independence?

For twentieth-century RLDS, it meant exactly that. For nineteenth-century RLDS, it may have meant moving to Lamoni, Iowa, which was seen as “on the edge of Zion” because it’s near the border between Iowa and Missouri. Then in the 1880s, RLDS started slowly moving back into Independence itself. The Church of Christ (Temple Lot) had been the first group to gather back to Zion, but they were so small that they did not make a major impact. The RLDS were the first ones to make a major impact in terms of numbers. By the early twentieth century, they were by far the largest church in Independence, and that continued all the way into the 1980s.

Who were some of the early Utah visitors who toured the Kirtland Temple?

One of the most famous Mormon visits in the early twentieth century was a group of LDS leaders who came through in December 1905. They had been to Sharon, Vermont, to dedicate a granite obelisk to Joseph Smith Jr. on the centennial of his birthday, and on the way back they stopped in Kirtland and took a tour of the temple.[2] And since they kept journals, there are at least four or five accounts that I’ve read of what they experienced on their tour.

The visitors showed different levels of politeness as they described what happened on that visit. I think they had a good time, but there was definitely tension. They visited the unheated temple on December 27, and Edith A. Smith said that it was evident there were two types of coldness in the building: “One the result of the temperature and the other a lack of [God’s] Spirit.”[3] There was already tension when Edith walked in, and I think she was looking in part to be offended. At the same time, they felt that the RLDS guide, who was an RLDS apostle, was a jovial individual, and they seemed to get along fi ne with him. They tried to get pictures in the temple with their Kodak Brownies, and their guide asked them to desist. But “before Brother B had been discovered,” Edith writes, “the Kodak had already got its work.” So even then there was tension about the control of that space and what happened inside the temple as the RLDS tour guides were taking you through.

The LDS guests who went through in the nineteenth and early twentieth century had the notion that this temple was used much as they understood their temples. So as they listened to the RLDS guide explain the use of the temple in the 1830s, they thought he had no idea what he was talking about. “To hear their [RLDS] explanations,” wrote Anthon H. Lund in his journal, “it was easily understood that they had no conception of the real uses of a Temple.”[4] Actually, what LDS visitors didn’t understand was the evolution of the temple space. So there was that misunderstanding as they were going through the tour. They were polite about it, but there was definitely this sense of ecclesiastical rivalry between the two groups. That had happened throughout the nineteenth century as well.

And as the twentieth century progressed, more and more LDS guests would visit the temple—not just leaders. By the 1930s, there were groups of average LDS people coming to the Kirtland Temple in big tours. And that really increased after World War II, when the number of people coming on bus tours and with their families on family vacations just exploded.

It seems to me that generations of Mormons have visited the Kirtland Temple wondering, “Where the heck is the baptismal font?”

I think any person who has guided tours through the Kirtland Temple has been asked that at a certain point. LDS temples have baptismal fonts to perform proxy baptisms for the dead, and this is something which was done in Nauvoo in the 1840s, i.e., after the Kirtland period. In the 1830s, this was not yet part of their theology.

An increasing number of guests, though, are informed enough to realize that didn’t happen here. In part they know that because since the 1980s the LDS Church canonized a vision that Joseph Smith had in the temple of his brother Alvin, who died in the 1820s (D&C 137). In the vision, Joseph sees Alvin in resurrected glory in the celestial kingdom and wonders how this could be, given the fact that his brother hadn’t been baptized. Joseph is told that those who would have received the gospel, had they been given a chance to hear it, will be heirs of the celestial kingdom.

So Joseph Smith is assured that you don’t need baptism, which kind of undercuts the whole reason for this ordinance of the baptism for the dead. But it is re-interpreted, of course, in contemporary LDS belief, as meaning that Joseph Smith was coming to understand that there would be a future time in which these ordinances could be administered. So Mormons have this idea that Joseph had this experience early on as an intimation of something that would come later. To that extent, they may be aware that there were not baptisms for the dead in the 1830s in the Kirtland Temple.

In terms of contemporary LDS temple rituals, my understanding is that there was a hint of starting washings and anointings in the Kirtland Temple.

That is correct. Washings and anointings are part of LDS temple rituals today, and there is a hint of that in what these early Saints were doing in Kirtland. They didn’t anoint different parts of the body and say prayers or blessings over them—that wasn’t happening in the same way as in LDS temples today, as a liturgical or set form. The Kirtland washings and anointing were less structured. Here they were washing feet, and they were washing their bodies with whiskey mixed with cinnamon, to give some aromatic scent to it, and the feel of the whiskey evaporating from the body produced a bodily sensation, too. The Holy Spirit was in that way felt, experienced, and ritually mimicked. Mormons felt they were re-living the ancient order of things, so they were trying to re-create priestly anointings described in the book of Exodus.

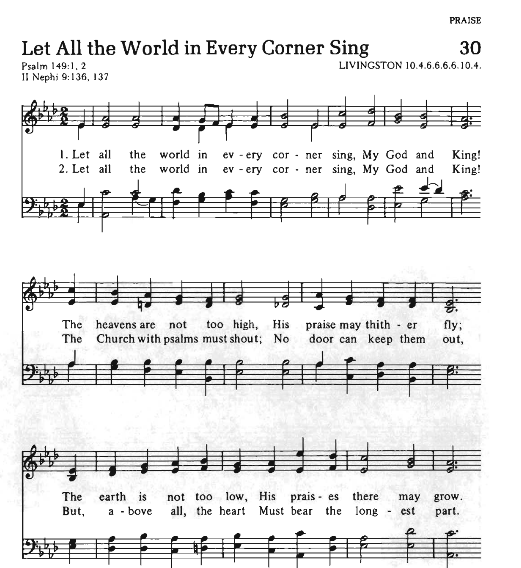

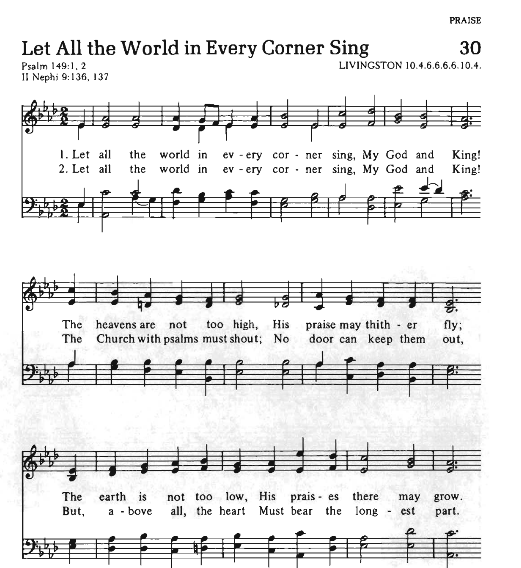

Even before the temple was finished, they performed these washings and anointings in the print shop, which was close to the temple. And when the temple was completed, the washings and anointings became part of the Kirtland endowment ceremony, which was not a secret ceremony. There were no parts of that ceremony which anyone took a covenant not to reveal, and they didn’t regard these rites as something they couldn’t talk about. They certainly talked and even sang about them! In the hymn “The Spirit of God like a Fire Is Burning,” one of the verses says,

We’ll wash, and be wash’d, and with oil be anointed,

Withal not omitting the washing of feet.

For he that receiveth his penny appointed

Must surely be clean at the harvest of wheat.[5]

What was the Kirtland endowment?

In the broadest sense, it seems to me that the Kirtland endowment was a recapitulation or reenactment of the Passion narrative and Pentecost.[6] So during the ceremony you had the washing of feet, as Jesus did with his disciples, and you had communion, which was a reenactment of the Last Supper.

This ceremony, by the way, was for priesthood holders, and it happened between the Sunday dedication and the second dedication that happened the following Thursday, so probably March 29–30, 1836. Leaders went through it first, and then all the priesthood holders who were in Kirtland went through it. It consisted of a kind of mass revival meeting where they prayed and prophesied. During the day they performed the rituals of washing of feet, anointing with oil, and laying on of hands to bless people, to “seal” them, as they used to say. The older notion of sealing was the salvation of the assured, but now there’s this assurance that you have this extra gift of power from the Holy Spirit.

For the Kirtland Saints, this endowment was what other Protestants would have called a second work of grace—something beyond baptism, what Methodists would have called sanctification. The Saints were looking for something similar. They felt that as priesthood, as ministers, they needed more of the Holy Spirit to go out to preach with power and authority, evangelize the entire world, and redeem the kingdom of God on earth into these gathered communities that they would create with just relationships, and bring to pass the wrapping up of the world before the Second Coming, which they whole-heartedly believed would happen in their lifetimes.

Tell me more about what happened during the Kirtland endowment.

The ceremony mimicked the high point of Christian redemption. It even included the Methodist-like practice of a “watch night” or vigil: they stayed up all night on the third floor of the Kirtland Temple. Staying awake all night in prayer and resisting sleep is, in a sense, a re-enactment of Gethsemane. They had been up already twenty-four hours when the gathering ended at four or five in the morning. And as they were in prayer, they spoke in tongues and felt that they had this Pentecostal power. They did the Hosanna Shout, which now LDS do at the dedication of all their temples. The early Saints performed it frequently in the Kirtland Temple, both around the dedication and in the Kirtland endowment. “Sealing up a covenant with Hosanna and Amen,” they would say.

These covenants were not the set promises that would develop later in Nauvoo, but were more informal. For instance, one of the darker things that they promised was to avenge themselves on their enemies in Jackson County if anyone should come against them again. This is biblical vengeance, Psalms-like vengeance; this, too, was part of the Kirtland endowment. I’m not sure if this carried over as they repeated the endowment subsequently, but it was certainly part of the 1836 ceremony.

The chorus of “The Spirit of God like a Fire Is Burning” was an approximation of the Hosanna Shout: “Hosanna, Hosanna to God and the Lamb.” And that’s an intimation of Jesus coming into Jerusalem, riding in, and the people greeted him with, “Hosanna, blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.”[7]

More radical Methodists shouted Hosanna when the Holy Spirit fell upon them. A radical Methodist thought that, any time the Spirit was present, a person couldn’t be quiet and had to shout Hosanna. So this was part of the worship experience that many of the Kirtland Saints were already familiar with, since maybe half of them had been Methodists at one point in their life. And this in a way is ritualized in the new Kirtland Temple.

In our day, when someone gets sick, we anoint them with oil and pray for them. In the Community of Christ we call this an administration, and in the LDS Church you may call it a blessing. And that began to occur with much more frequency after the Kirtland endowment, which included so much washing and anointing. So a whole sacrament in the Community of Christ, or an ordinance in the LDS Church, was born out of this experience. After the Kirtland endowment, elders everywhere were anointing the sick with oil and praying. So it became routinized, a regular part of their worship life.

A lot came out of the Kirtland endowment in terms of ritual. Some parts evolved in some inchoate form into the first part of the LDS endowment as administered in Nauvoo, but other parts were never performed again in the same exact way.

Was the Kirtland endowment performed only once?

At fi rst they intended to do it once. But then they realized that not everyone was there, so they repeated the endowment several times in 1836. And by 1837 they realized that they had new people who weren’t around in 1836, or who weren’t yet part of the Church, so they went through this endowment again. Wilford Woodruff, who was at that time ordained to be a Seventy, wrote in his journal that the Kirtland endowment was to be practiced every April 6 until the Second Coming of Jesus.[8] So they anticipated doing this over and over again, almost like an annual revival meeting.

Christopher Jones has done some great work in comparing the Kirtland endowment to what Methodist ministers experienced in revival meetings.[9] Methodist ministers would often go to revival meetings to be themselves renewed, and in some ways the Kirtland endowment was a rough equivalent to that: priesthood holders could come to be renewed again through this ceremony. So what the early Saints did was to take the Methodist revival meeting and add a heavy ritual emphasis, in this way making it their own.

Let’s move forward to the history of Kirtland since the 1950s. What are some of the developments worth mentioning?

As the number of LDS traveling to historic sites increased, the LDS Church started thinking about buying sites in Ohio. They first purchased the John Johnson Farm, which is about thirty miles from Kirtland. With that purchase, they were slowly re-establishing their historical presence. Then in the 1960s a private LDS investor, Wilford Wood, bought the Newel K. Whitney store, located about a quarter of a mile north from the temple. Wood kept that property in trust for the LDS Church until a certain point in time when they wanted to interpret Kirtland as a historic site.

The RLDS Church also moved toward expanding its interpretative center in Kirtland. In the late 1960s, the RLDS Church built its first visitors center. It was tiny, but it meant that they could show a film and display some artifacts. They were trying to mimic what you see across America. Visitors centers were growing everywhere. With the expansion of the interstate system, many middle-class families who owned automobiles were going on vacations. All of these factors set Kirtland as a destination not only for Latter Day Saints, but also for people interested in Ohio history.

So people continued to flock to Kirtland. By the 1970s LDS members had established a presence in Cleveland, with probably several thousands in the Greater Cleveland metropolitan area, and they decided that they wanted an LDS visitors center in Kirtland. That started a process that eventually resulted in Historic Kirtland, an LDS campus around the Newel K. Whitney Store, which was dedicated in 2003.

It was a fascinating case: The impetus started with local members clamoring for a visitors center, rather than top-down instructions from the hierarchy. The hierarchy had to agree, of course, but it was the local people who convinced the hierarchy that the Church needed a presence in Kirtland.

What is the “Kirtland Curse”?

It’s a complicated story. By the 1970s, key LDS local leaders began believing that Kirtland had been cursed in the 1840s by the Lord. This group included Karl Anderson, a well-known local LDS leader who became stake president. They based this belief on statements by Joseph and Hyrum Smith. One of the statements by Joseph Smith is in the current LDS Doctrine and Covenants (D&C 124:82–83). It was canonized by the LDS Church in 1876, so it’s not part of the Community of Christ’s Doctrine and Covenants. Verse 83 declares that the Lord has “a scourge prepared for the inhabitants” of Kirtland.

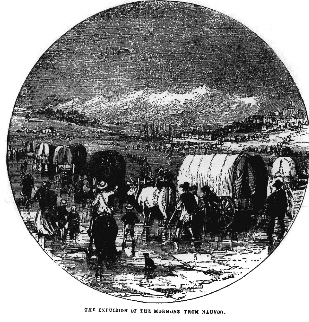

Hyrum Smith’s statement is an 1841 letter that he wrote to the Saints who were living in Kirtland. British converts stopping in Kirtland were being persuaded by local Saints that Kirtland was a great place to live. So they were settling there, instead of going to Nauvoo. The problem was that the Church at the time had invested an enormous amount of money in land in Nauvoo, and if they were not going to default on their loans, they needed Church members to buy that land. So Hyrum Smith issued a “thus saith the Lord” statement in which he commanded all the Saints living in Kirtland to go to Nauvoo, adding that their Kirtland properties would “be scourged with a sore scourge” and that many days would pass before they could possess them again in peace.[10]

The Saints in Kirtland wrote back and said to Hyrum, “Actually, we’ve organized ourselves quite well here. We’re taking care of the poor. We’d like to continue on here in Kirtland.” Hyrum wrote back and said “O.K., you can stay, but don’t expect Kirtland to rise on the ruins of Nauvoo.”[11] So the matter was at the time more or less settled. But if you don’t have the rest of the story, if all you have is the Hyrum Smith letter, and if you think that it was literally a revelation from God, instead of being part of this drama of trying to convince the Saints to move to Nauvoo, then you’re going to look back and read that letter and say, “Kirtland is cursed!”

In 1974 Karl Anderson read these and other Mormon writings and became convinced that Kirtland was cursed. I think for local LDS members this worked as an explanation as to why the LDS Church didn’t own the Kirtland Temple, i.e., because the Lord cursed it in the 1840s. And they thought, “If the temple is cursed, but we will possess it in the future, maybe then we are part of redeeming Kirtland.” So suddenly these Mormons felt they were an important part of God’s redemptive action in the world.

What did Karl Anderson and other Mormons do to “redeem Kirtland”?

Karl Anderson came up with a three-fold solution for how to redeem Kirtland from the curse. First, they would bring missionaries so that the gospel would be preached in Kirtland for the first time since the 1840s (which of course was an insult for the RLDS because they had been there continually). Second, they decided that they needed to establish a ward and a stake in Kirtland. Third, they concluded that they needed to establish a visitors center. Karl believed that this plan would be an integral part of lifting the curse on Kirtland—helping God reclaim the place and, if you read between the lines, eventually redeem and get back the Kirtland Temple for the LDS Church, with everything in its own order and in its own due time.

This story of the curse was not widely known by LDS members, but Karl began talking a lot about it. In 1976, Donald Brewer, president of the LDS Cleveland Ohio Mission, arrived here, heard Karl talk, and got really worried. He read and prayed about it, and he was convinced! “There’s a curse, there’s a scourge here in Kirtland, and we need to lift it.” So he was totally on board, and Karl and President Brewer worked together to try to lift the curse. They got missionaries to walk around Kirtland, evangelizing again. And when they got an RLDS family to convert, they were ecstatic and believed that the curse was indeed lifting!

When LDS General Authorities were in the area, Karl would take them to Kirtland on tours, show them around, and if they hadn’t known about the scourge before coming to Kirtland, they certainly knew by the time they left. By 1979, Karl and other local LDS members had a local architect draw plans for a visitors center, and they printed a brochure about it that looked very professional. But it got lost in the bureaucracy of Salt Lake and never got the attention of the apostles.

Did they eventually get the attention of Salt Lake leaders?

Because of his unique access to General Authorities, Karl eventually managed to get the proposal on the desk of the right apostle, who then brought it to the Quorum of the Twelve. Some of the apostles were opposed. “We’ve already put so much money into Historic Nauvoo,” they complained. “We should be spending more money on the missionary program—not historic sites and buildings.”[12] But Ezra Taft Benson, who was at that time president of the Quorum of the Twelve, had become a great advocate for the project and broke the deadlock. “We will not have another Nauvoo,” he said, “but we will have a Kirtland, and it will be as it should be.” And that’s how they authorized the construction of the visitors center.

By October 1979, the last part of Karl’s plan to lift the curse was in place: they broke ground in Kirtland for a new LDS chapel that would become a stake center. Ezra Taft Benson attended the ceremony. “The curse that the Lord placed on Kirtland,” he told the congregation during his speech, “is being lifted today.” And during his prayer, he formally lifted the scourge that was on Kirtland. Latter-day Saints saw this as a redemptive process of remaking Kirtland.

By 1984, the Whitney Store was restored and re-dedicated, becoming a more prominent historic site for the LDS Church. Ezra Taft Benson and Gordon B. Hinckley attended the dedication, and they talked about the spiritual visions and dreams that happened there: John Murdock seeing Jesus in the Whitney Store, and Joseph Smith organizing the School of the Prophets.[13] Thus Church leaders were starting to assure LDS that they may not have the temple, but they did have a place where Jesus appeared in Kirtland.

I think this was part of the greater narrative in which people believed that the curse was being lifted. It wasn’t just Karl Anderson who believed that this was happening—it was widespread at that time among Cleveland LDS members who had heard Karl talk about this and now felt part of God’s redemptive plan in Kirtland. The RLDS were vaguely aware that LDS held this belief, and yes—the notion that their own activities were part of a curse was mildly insulting to them. It implied that they were on the wrong side of God! But it seems to me that this was a way for LDS to attempt to explain why they were not in control of the temple.

And then as time went on, I believe Karl himself began thinking. “Maybe also the RLDS have been part of lifting the scourge on this place.” So he eventually included them as part of this process by which God was redeeming Kirtland and making it into a holy place again, thus creating a more generous narrative of curse and redemption.

Could another factor have been the process by which the RLDS Church has become less obsessed with its past?

I think that happened only in the 1990s. Through the 1980s, the RLDS focused heavily on its past. And then in the 2000s there was a reinvigorated emphasis on Church history in Community of Christ. As much as LDS would like to think that Community of Christ no longer values Church history (and at least some LDS believe that), if you look on the ground, people are still interested in the history of their church, and there was even a greater emphasis in the 2000s. This visitors center in Kirtland, where we’re having this interview at, is one of the results of that—it was built in 2007 after a long process of raising money. Community of Christ is small, it’s not even as large or financially powerful as it was in the 1970s, so I think this visitors center is a statement that they still value the heritage—in a different way. They can’t value it in the same way—no one ever does!

So there’s a renewed emphasis on history in Community of Christ. If Nauvoo represents a problematic, uncomfortable time period for Community of Christ—because of issues such as militarism, theocracy, and plural marriage—Kirtland, even with the conflicts that happened here, with the breakup of the bank and arguments around that,[14] is seen much more positively. People can still rally around and think of the dedication of the first worship building, the first temple in Community of Christ tradition, and what it means to them, and almost universally they have a positive image of Kirtland. And that’s true whether you’re talking about Saints in Independence, Missouri, or Saints in Manihi, French Polynesia. They universally think of the Kirtland Temple as a sacred place.

In 1994, the Community of Christ dedicated a temple in Independence. How does that edifice relate to the historic Kirtland Temple?

The modern temple in Independence was built on a portion of the land dedicated by Joseph Smith Jr. in Missouri in the 1830s for a temple site. When they drew up the plat for the City of Zion in 1833, they placed twenty-four temples in that plat—they drew up the plans right here, in Kirtland, probably only a few yards away from where we’re having this interview. And the Independence Temple is on the footprint of at least three of those planned temples, so it’s literally on land that was intended for temples in the 1830s, for that redeemed city of New Jerusalem.

The Independence Temple functions in some ways like its Kirtland ancestor. For instance, the Kirtland Temple had Church administrative space—an office for the Church president. The Independence Temple has the offices for the president and the apostles who live in that area. (Some apostles now live in their fields, which could be as far away as Honduras, French Polynesia, or Zambia.) The Independence Temple, like the Kirtland Temple, also has a space for education: the Community of Christ Graduate Seminary, which amounts to a Masters of Arts and Religion, where people gather for classes. And we also have the Peace Colloquy, which happens every October in Independence.

The Independence Temple is also a place of worship. The Daily Prayer for Peace happens in the Independence Temple. (By the way, we also do the Daily Prayer for Peace in Kirtland, but we do it in this visitors center, instead of the temple, in part because we light candles and we don’t want to create a fire hazard in the historic temple.) So doing the Daily Prayer for Peace in the Independence Temple is a continuation of the notion that the temple is a special worship space. Also from the Independence Temple, Steve Veazey, Community of Christ prophet, gives an annual address to the Church that is then broadcast via the web.

So I mentioned three areas of correspondence between the Kirtland and the Independence temples: administration, education, and worship. And even though we don’t do a Kirtland-style endowment, all the sacraments of the Church, except for marriage, can be performed in the Independence Temple. People may go there for their evangelist blessing, which is the equivalent of an LDS patriarchal blessing, or an administration (health blessing), or communion, which in the Community of Christ consists of bread and “wine” (grape juice).

And the Kirtland Temple here is also used today much as it was in the 1830s, minus the Kirtland endowment. In the 1830s the temple was a space for public worship, and they also had tours of the temple—not only before it was dedicated but also after; at that point we did not yet have the notion that only people who have made certain covenants should be allowed in. In the 1830s they charged 25 cents, which was actually pretty expensive for just a tour! And you saw everything in the temple, they took you floor by floor. And on the third floor, which is the top floor, they had the Egyptian mummies associated with the Book of Abraham. By 1837, tourists were going through the Kirtland Temple, and some published their accounts.

Let’s move to the recent past. What was the process by which Community of Christ started to share the Kirtland Temple with the other branches of the Restoration?

That process happened in the 1990s. In the era before that, the Kirtland Temple was basically a worship space for the RLDS congregation. In 1959 the congregation moved across the street to their present space, but even at that era the temple continued to be used at Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter for community services in which the entire Kirtland community came together in ecumenical worship. Through the 1940s, the temple was the center and the symbol of the community, and in the 1940s most of that community was RLDS—though there were also Catholics, Congregationalists, and other faiths. So at least since the 1940s, all those groups traditionally have come together for community services in the Kirtland Temple.

Then in the 1990s, the building was opened up for the LDS also to have services there. That was in a sense a community outreach by the Community of Christ. At first they allowed it on a limited basis, but now they allow it a lot more frequently. In the course of a year, there might be fifty services in the Kirtland Temple; a couple dozen will be sponsored by the Community of Christ, but another couple dozen are going to be LDS.

We always have staff to accompany LDS groups, and LDS would probably use it more if we could schedule more staff to be there. LDS can have a sacrament meeting there, but we ask the groups not to perform any sacrament or ordinance other than the Lord’s Supper. Testimony meetings are very popular—especially with LDS youth groups. The temple is scheduled for both local LDS groups and cross-country pilgrimages that come through Kirtland by bus all the time, especially in the summer.

What percentage of the visitors you receive are LDS?

A realistic estimate is that 90–95 percent of our visitors are LDS. The official number is 50 percent, but that’s calculated only from those who fill out a comment card and indicate their religious affiliation. In any given year we have approximately 25,000 people going on a tour of the temple, although the year Historic Kirtland (the LDS site) opened, we had close to 40,000. Even in the 1920s, a significant percentage of visitors, though less than half, were LDS. In the 1970s, a larger percentage of visitors were Community of Christ, because there were more RLDS in this area and there was an extensive program of weekend retreats which every year would bring as many as thirteen RLDS congregations to Kirtland. That ended in the mid-1970s, when the local congregation who was sponsoring these visits got burned out on the program.

After having been through several tours of the Kirtland Temple, my perception is that LDS visitors tend to be very gracious guests, but on occasion they cannot help it and they have to ask a question that attacks the Community of Christ.

Most people going to historic sites across the country know relatively little about them when they step in the door. At the Kirtland Temple, we generally have the opposite. LDS visitors might not know the views of current historians, but they know stories about the temple, and it’s already part of a narrative that they have of their spiritual past and their spiritual ancestors. This makes it a different experience—this is a pilgrimage site for many people. That generates a sense of reverence and sometimes discomfort—especially around the fact that this is a pilgrimage site that they, the LDS, don’t own.

Add the fact that this is not exactly like the tour they would experience at an LDS site. Some LDS frankly don’t like LDS historic site tours; some love them. I think the majority love them and a growing minority don’t like them. The majority of LDS tourists who come have been through an LDS tour where someone is testifying along the lines of “I know this happened, in the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.” LDS visitors will notice that this doesn’t happen in our tours. So that already creates a sense of tension. Many of them may feel that it’s more like a historical tour, so they may not get exactly the religious experience they were looking for.

And at times there’s adversarial tension too, along the lines of, “Let’s see if we can trip up the guide.” A few visitors may think, “These Community of Christ guides don’t really know Church history—let’s see if we can make them look silly.” That occasionally happens. But the vast majority are very gracious and very kind. And even if they have questions, sometimes they don’t even ask them: they hold back or they ask the LDS tour director—and who knows what the tour director answers! I think it’s a way of being polite and saying, “OK, we have our differences, and I won’t try to make my discomfort public and make the guides uncomfortable.” So I think there’s a good deal of graciousness that happens, too, in these interactions.

I was once touring the temple with an LDS family, and they were all very polite—except for the Grandpa! As soon as we sat in the lower court, he asked the guide in an accusatory tone, “Why is it that you guys no longer tell the story of Jesus Christ appearing to Joseph Smith in the temple?”

Some guests will come out and say that, but the vast majority won’t. When I was a regular temple guide, I sometimes guided junior high groups. As you know, junior high kids sometimes believe they know everything! And some of these kids would treat me harshly. Maybe that had to do with the way their leaders prepared them, too. The entire time they were asking me questions like, “Why don’t you believe in the First Article of Faith?” Apparently the intent was to rebuke me for not believing that God the Father has a physical body, which of course is not what the First Article of Faith says.

And these kids went through all the hot-button social issues and made me defend the Community of Christ on women, and LGBT issues, and peppered me with questions. So I finally said, “You know—I’m happy to answer these questions, but I would like to talk about the temple, too. So let’s go downstairs and talk about the 1836 dedication.” And things ended a lot better on that tour. So on occasion we have tours where people want to argue. And I understand that, because when I was a teenager, I was a very conservative RLDS member raised in a very conservative RLDS home, and I would go with my youth group friends down to the LDS Visitors Center in Independence to argue! So I can be empathetic when people sometimes come at me—I can imagine what I was like, too, at a certain point in my life.

You describe the Kirtland Temple not only as a place of contestation, but also cooperation.

That’s right. Besides the services where LDS worship on their own, there are cooperative services through the year. Since the 1980s, the LDS staff of Historic Kirtland will help out with the Christmas and Easter services.

In a few days, we’ll have the Emma Smith Hymn Festival that began in 2004, on the 200-year anniversary of Emma’s birth, which is July 10. The hymn festival has a little script, and some parts are read by sister missionaries from Historic Kirtland. These missionaries are also part of the choir that sings “The Spirit of God like a Fire Is Burning” and “Redeemer of Israel.” The congregation, which is mostly LDS and local Community of Christ folks, is invited to join in singing these hymns. So it’s another example of those ecumenical traditions of cooperation that have grown up at the Kirtland Temple.

Certainly the relationship with the LDS has grown less adversarial over time, and the points of contention have changed over time, too. I think that shift reflects the changes in American denominations. Some sociologists and religious studies scholars talk about religious realignment, not just over denominational differences, but differences along a liberal/conservative social divide. And since the 1980s, the Community of Christ has been squarely on the progressive side, and the LDS Church has been on the conservative side, so that produces a new set of tensions. I do not think many Community of Christ members today care too much about arguing over nineteenth-century issues such as presidential succession, but they would really care about social issues. This provides a new area of contestation on temple tours—although not as frequently as in the mid-2000s.

So there’s still a sense of construction of otherness, not only by LDS visitors but also on the part of the Community of Christ guides giving the tour. If LDS missionaries go on missions and come back converted, a Community of Christ guide who gives tours every day in the Kirtland Temple comes back from that experience thinking that the Community of Christ is awesome, and probably thinking they never want to be LDS!

After a while, a sense of difference develops in these guides. And I’m sure that happens as well to some LDS who go through the temple tour. They may end up thinking, “No doubt the Community of Christ has lost the authority and gone off on this apostate road,” etc. Other LDS visitors come out thinking, “These guys are our friends.” So it’s a way for them to make kinship with the group, or extend a more limited notion of ecumenical encounter, even if brief. And I think, for a lot of LDS, the Kirtland Temple tour experience is a combination of both—a way of making friendship while at the same time establishing difference.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Kim L. Loving, “Ownership of the Kirtland Temple: Legends, Lies, and Misunderstandings,” Journal of Mormon History 30, no. 2 (2004): 1–80.

[2] See Proceedings at the Dedication of the Joseph Smith Memorial Monument (Salt Lake City: 1906), 68–69; see also Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), chap. 5.

[3] Edith Ann Smith, “Journal,” December 27, 1905, MS 1317 FD.1, LDS Church Archives.

[4] Anthon H. Lund, Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921, edited by John P. Hatch (Salt Lake: Signature, 2006), 328.

[5] Fourth verse of 1835 LDS hymnbook. Most of the twentieth-century editions of this six-verse hymn, both in the LDS and RLDS traditions, present the hymn in shortened versions that skip this verse.

[6] See Gregory A. Prince, Power from On High: The Development of Mormon Priesthood (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1995), 115–49 and David John Buerger, The Mysteries of Godliness: A History of Mormon Temple Worship (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 11–34.

[7] Matthew 21:9, Mark 11:9, and John 12:13. See Jacob W. Olmstead, “From Pentecost to Administration: A Reappraisal of the History of the Hosanna Shout,” Mormon Historical Studies 2 (Fall 2001): 7–37; Steven H. Heath, “The Sacred Shout,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 19 (Fall 1986): 115–23.

[8] Susan Staker, ed., Waiting for World’s End: The Diaries of Wilford Woodruff (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1993), 13.

[9] Christopher C. Jones, “‘We Latter-Day Saints Are Methodists’: The Influence of Methodism on Early Mormon Religiosity,” MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 2009.

[10] Times and Seasons 3 (November 1, 1841): 589.

[11] Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Richard Lloyd Anderson, eds., Journals, Volume 2: December–April 1843 in THE JOSEPH SMITH PAPERS, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 340.

[12] The LDS Church had been investing heavily in Nauvoo since the 1960s by buying land, restoring historic properties, and building many new structures. See Julie Dockstader Heaps, “Nauvoo ‘Beautiful’ Once Again,” Church News, June 29, 2002.

[13] “Restored Whitney Store Dedicated in Kirtland,” Ensign 14, no. 11 (November 1984): 110–11.

[14] The 1837 failure of the Kirtland Bank, with its ensuing conflict and dissent, is widely considered the main reason why Joseph moved Church headquarters from Kirtland to Nauvoo.

[post_title] => The Kirtland Temple as a Shared Space: A Conversation with David J. Howlett [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 47.1 (Spring 2014): 104–123An oral interview between an LDS Member and a Community of Christ member regarding the history of the Kirtland Temple. They explain that despite differences in religious beliefs, people can still form friendships and cooperate. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => the-kirtland-temple-as-a-shared-space-a-conversation-with-david-j-howlett [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-09-09 01:54:04 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-09-09 01:54:04 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=9433 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Grant McMurray and the Succession Crisis in the Community of Christ

William D. Russell

Dialogue 39.4 (Winter 2006): 67–90

Members of the Community of Christ were shocked when our president, W. Grant McMurray, announced that he had resigned on November 29, 2004 , effective immediately.

Members of the Community of Christ were shocked when our president, W. Grant McMurray, announced that he had resigned on November 29, 2004 , effective immediately.

[post_title] => Grant McMurray and the Succession Crisis in the Community of Christ [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 39.4 (Winter 2006): 67–90Members of the Community of Christ were shocked when our president, W. Grant McMurray, announced that he had resigned on November 29, 2004 , effective immediately. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => grant-mcmurray-and-the-succession-crisis-in-the-community-of-christ [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-10-11 21:01:17 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-10-11 21:01:17 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=10244 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

Is Joseph Smith Relevant to the Community of Christ?

Roger D. Launius

Dialogue 39.4 (Winter 2006): 58–67

I spoke as a member of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints/Community of Christ. As a result, I had a decidedly different perspective on Joseph Smith than my co-panelists.

In the spring of 2005 Newell Bringhurst asked me to participate in a session of the Mormon History Association's annual meeting. Because it was the bicentennial of Joseph Smith's birth and we were meeting in Vermont, his birth state, our session was titled "In Pursuit of the Elusive Joseph Smith." He asked each panelist to consider the process of investigation and interpretation that has been made over the past forty years in terms of the most significant works produced, what significant areas of Joseph Smith's life remained to be explored, and whether a reasonably "definitive portrait” of Joseph Smith is more possible today than it was forty years ago. I agreed to participate in this session, along with four senior scholars in Mormon studies, D. Michael Quinn, Glen M. Leonard, Dan Vogel, and Grant Underwood. The session proved both stimulating and provocative, and hopefully useful to the audience in attendance. The following essay is a slightly revised draft of my remarks.

I spoke as a member of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints/Community of Christ. As a result, I had a decidedly different perspective on Joseph Smith than my co-panelists. In addition, with the peculiarities of the history of my faith community, Joseph Smith Jr. has enjoyed a place in this religious tradition strikingly different from that he has attained among the Utah-based Latter-day Saints. Without question, he is much less revered and less legendary than among the Latter-day Saints, for whom Joseph Smith is significant, not just for his life but for his religious innovations. l have heard this assertion many times and in many places. As Ronald K. Esplin commented in an important essay about Nauvoo, "Nauvoo was, and is, and will be important to Latter-day Saints because it was the City of Joseph. It was the city he built, where he lived and acted, where he died. Above all, it was the city where he fulfilled his religious mission. . . . In a very real sense, his other labors were prologue.”[1] Clearly Smith's religious innovations are central to the LOS reverence for the founding prophet.

I would compare this perspective to one debated among various other Christian groups. Which is more important: the life of Jesus or the death and resurrection of Christ? Allowing that both are significant, the relative importance that one would place on these events tells us much about the group's perspective. To emphasize the life of Jesus is to embrace an entity fully human who had to come to grips with the duality of his humanity and divinity and did so only with great difficulty and strength but ultimately with acceptance. To emphasize the death and resurrection of Christ is to accentuate divinity while too often giving short shrift to the struggle that Jesus engaged in throughout his life. Utah-based Latter-day Saints tend to emphasize the triumphant Joseph Smith (at least as they conceive of him) who "completed" his work of restoring the gospel before his assassination at age thirty-nine.

For the Community of Christ, Joseph Smith's place is much less assured and certainly far less triumphant. Indeed, I know of no one in the organization who would conclude that Joseph Smith "completed" his work of restoration, and I could poll many who would question the totality of what he accomplished. I would contend that Joseph Smith's activities represented a conflicting set of ideals for those identified with the Community of Christ. Such was the case from the time of Joseph Smith III, first president of the Reorganization, in the nineteenth century, and it has remained so to the present, becoming even more problematic in the last twenty-five years or so. Over the course of many years, the Church has cast aside any belief in plurality of gods, baptism for the dead, and temple ceremonies as understood by Latter-day Saints. From the beginning of the Reorganization movement, it rejected celestial marriage and the tendency toward militarism and official involvement in most political activities that were prevalent in Nauvoo. While some in the Reorganized Church refused to believe that these had any place in the organization of Joseph Smith's day—and this has been a source of tension for those inside the Church—the reality is that, in a demythologization of history, many have come to accept that not everything Smith did was appropriate. At a fundamental level, the lifetime of contradictions that Joseph Smith lived represented both a triumph and a tragedy, the backlash of which the Community of Christ’s adherents have been seeking to understand and in some cases to live down ever since.[2]

At the same time, there is a dichotomy between what some of the Church's historians might understand about the past and what the average member believes, so while there is some consensus there is certainly not unanimity in the construction of a faith story about Joseph Smith. This came home to me quite pointedly in the context of a request recently from the junior high Sunday School teacher. She asked, "What should I tell my students about Joseph Smith?" I asked her what was in the curriculum, and she told me that it was completely silent on the subject. Accordingly, her class was asking questions for which she had no resources. This situation raised a critical question. What might we say about the founder? Having deconstructed his life and mission, how might we work to reconstruct a meaningful story that celebrates his legitimate accomplishments while remaining honest to the historical record? I had no answer for this instructor, and I still do not.

Few of the major incidents that have been a part of the Community of Christ faith story remain salient. These include the translation of the Book of Mormon, the restoration of the priesthood and the gospel in its fullness, the development of a uniquely useful theology, the concept of Zion, belief in the Second Coming of Christ and the millennium, and several others. What remains is a deeply flawed character at the center of the Church's origins.

How might a re-enchantment of Church history be accomplished? Might we do so by asking the question: "Could any other person have been the founder of the restoration movement?" No doubt, historical developments are important to the identity of the Community of Christ, but how might members accept the historical record "warts and all" but still see Joseph Smith as unique in some respects? lt remains a puzzlement.

There are many difficult examples of what the Community of Christ has been seeking to deal with. The quest for Zion was an attractive idea for the Church for more than a century, and the success of Smith in such places as Nauvoo has often been viewed as the closest approximation the Church has to the ideals of Zion carried in scripture and doctrine. At the same time, the Reorganized Church/Community of Christ has been repelled by the darker side of political power—corruption, influence-peddling, and the difficulty of political choices. Much the same was true when considering Smith's truly weird theological experimentation.[3] Many in the Community of Christ today are certainly uncomfortable with Smith's authoritarianism, with his militarism, and with his sense of being God's chosen. I know of no one in the leadership of the Community of Christ who accepts the Book of Mormon as a work of history, even if they view it as scripture. Of course, some rank and file members still accept it as such. As to the many doctrinal idiosyncrasies that emerged from the mind of Joseph Smith, those are sometimes viewed as the ramblings of a misguided fanatic.[4] That he became increasingly egocentric and power hungry is a given for virtually all Community of Christ members.

But I suspect that many members still view his early structuring of the Church and its basic doctrines as prophetic. Even so, their view of his prophetic role in the Church is severely limited when compared to the view of the LDS Church and perhaps to early RLDS views. By distancing itself from many of his actions and selectively emphasizing his prophetic role, the Community of Christ views him as more human than he is in the LDS tradition. His Nauvoo innovations are an "embarrassment," but many still view him as a figure of significance in the formation of the Church.

Accordingly, the Community of Christ has walked a fine line in interpreting the legacy of Joseph Smith. From a theological perspective, the Reorganized Church essentially rejected Smith's radical ideas. Between 1830 and 1844, and especially in the latter years, Smith promulgated a series of unique ideas on eternity, the multiplicity of gods, the possibility of progression to godhood, celestial and plural marriage, baptism for the dead, and other ideas associated with Mormon temple endowments—none of which found a place in the Reorganized Church.[5] A few of these innovations were simply considered quaint by non-Mormons; others, such as plural marriage, aroused volatile emotions and became rallying points for opposition to the movement.[6]

For many reasons, the Reorganization for over a hundred years desired to remain faithful to the stories, symbols, and events of early Mormonism, on the one hand, even as it sought respectability among Christians of other denominations.[7] To a remarkable extent, it was successful in doing so. These tensions were held in creative balance until a theological reformation in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Its success was largely due to the unique heritage of the Reorganized Latter Day Saints as the people in the middle, seeking to steer between the Scylla of excessively authoritarian, speculative, Nauvoo Mormonism and the Charybdis of creedal, congregational, Protestant sectarianism.[8]

The recent broad-based reformation has resulted in the virtual abandonment of most of the vestiges of Mormonism that informed the movement for a century and in their replacement by more mainline Christian conceptions.[9] In the process of that reformation, the character ofJoseph Smith has become an embarrassment. He is often viewed as a skeleton in the closet of the Community of Christ. After all, he was a cult leader who preached doctrines anathema to many Christians, engaged in sexual hijinks of the worst order, sought to cake over the United States and make it into a theocracy with him in charge, and, failing that, allowed himself to be martyred as a rallying point for his followers.

In this context, attempts to understand and explain the life and activities of Joseph Smith Jr. for the Community of Christ membership are not particularly necessary or valued. At this point, I can no more envision the preparation of a new biography of Joseph Smith usable by the Community of Christ than I can foresee the centrality of a new biography of Charles Darwin to the current debate over evolution/intelligent design. Joseph Smith is not truly germane to the current Community of Christ direction.

Having offered this lengthy preamble, let me address the questions that Newell Bringhurst suggested that we consider in relation to Joseph Smith.

1. How much progress has been made over the past forty years in terms of the most significant works produced?

This is an interesting question and one that I wish I had a better answer to, but the reality is that, while we now know much more about the details of Smith's life than in the past, I'm not sure that we have more understanding. Fawn Brodie laid out the major parameters of the questions most people pursued concerning Smith in her 1945 biography, and it is still by far the best work on the subject.[10] Few have moved far from the research agenda she laid out.

In No Man Knows My History Brodie systematically dealt with five basic issues that have challenged Mormon historians ever since.

- Joseph Smith's First Vision.

- Treasure seeking and its relationship both to Smith and Mormon origins.

- The origins and content of the Book of Mormon.

- The origins of plural marriage and other theological innovations.

- Joseph Smith, theocracy, and authoritarianism.

Because of our pursuit of these major issues, we have learned an enormous amount about Smith's work. We are all indebted to the historians who have explored these issues in depth and broadened our knowledge. Donna Hill's 1977 biography tried to deal with these issues comprehensively and was largely successful but failed to replace Brodie's book as the standard account of Smith's life, at least among the larger community of historians and observers.[11] Perhaps Richard Bushman's new biography of Smith will accomplish that task, but such a determination comes only with time.[12]

The reason a definitive biography of]oseph Smith is such an elusive goal is because Mormon historiography has become such a battleground in the last twenty years. I'm uncertain if believing LOS scholars can write anything but "faithful history" any longer, emphasizing exclusively the sacredness of the story of Mormonism. From John Whitmer to the present, most writing on the Mormon past has been oriented toward producing a narrative of use to the membership. The result was a thrust of historical interpretation that overwhelmingly emphasized God's word as defined by the Mormon prophets, spreading throughout the world in a never-ending advancement of the Church. Most LOS historians have accepted this interpretation because, as Klaus J. Hansen has suggested, most of them are members of the Latter-day Saint faith community, and they must overcome years of religious training that predisposes them to view the Church, its leaders, and its institutions as righteous and just.[13] LDS Apostle Boyd K. Packer has even invoked an espousal of the progress of Mormonism as a religion as the primary purpose of historical investigation, telling Church educators in 1981: "Your objective should be that they [those who study Mormon history] will see the hand of the Lord in every hour and every moment of the Church from its beginning till now."[14] With such a perspective, Church-mandated interpretations of the Mormon past are not easily overcome. And while Bushman is certainly an able and elegant historian with special skills in presenting the faith story, his book will be acceptable mostly to believing Mormons.

2. What significant areas of Joseph Smith’s life remain to be explored?

There is one huge area in Joseph Smith's life that I would like to see explored. It relates to his place in the myth and memory of the Latter-day Saints. No area in historical study has been more significant in the recent past than the study of memory. The reality of what happened in the past—which in any event is unrecoverable—is decidedly less important than what the population who values the story believes about it. So what do the Mormons believe about Joseph Smith? How did they come to believe this, and why? How have these beliefs morphed over time and in response to what triggering events? Of course, Joseph Smith is a legend. He is a legend in the same way that Wyatt Earp, Jesse James, Daniel Boone, Alvin York, Henry Ford, and a host of others in American history are legends. Unpacking the legend and exploring his myth and memory offer a new understanding on his place in the development of this important American-originated religion.

3. Is a reasonably “definitive” portrait of Joseph Smith more possible today than it was forty years ago? Why or why not?

I would suggest that there is no such thing as a definitive work of history. At some level, this question depends on the concept of "truth"—whether it exists and, if so, whether it is "knowable." I question both assumptions, although I would never argue definitively about them since I don't really know.

What we think of as truth has changed fundamentally with time. I am reminded of a scene from the classic comedy, Men in Black, that is really a commentary on the nature of modern society. The Tommy Lee Jones character, K, tells the Will Smith character about the reality of aliens in America. He adds, "Fifteen hundred years ago, everyone knew that the sun revolved around the Earth. Five hundred years ago, everyone knew the world was flat. Yesterday you knew that we were alone on this planet. Imagine what you'll learn tomorrow."[15] Imagine how truth has changed over time! Truth is inexact and difficult to pin down, always changing in relation to other events, perceptions, and countervailing ideas, especially over time.

Indeed, truths have differed from time to time and place to place with reckless abandon and enormous variety. Choice between them is present everywhere both in the past and the present; my truth dissolves into your myth and your truth into my myth almost as soon as it is articulated. This pattern is reinforced everywhere, and the versions of truth espoused by various groups about themselves and about those excluded from their fellowship are often misunderstood. Perhaps Pontius Pilate framed the dilemma best two millennia ago when he asked Jesus, "What is truth?"[16] But he never got an answer from Jesus. That silence says much about the nature of truth.

So, having followed this divergent trail about the nature of truth, let me suggest that there is no chance whatsoever of any historian producing the definitive biography of Joseph Smith. But that is because I reject the premise of definitiveness, not because excellent works will not emerge. Indeed, I hope they do—and soon.

[1] Ronald K. Esplin, "The Significance of Nauvoo for Latter-day Saints," Journal of Mormon History 16 (1990): 72.

[2] This was one of the themes of my dissertation, published as Joseph Smith III: Pragmatic Prophet (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988). On the RLDS reformation, see Larry W. Conrad and Paul Shupe, "An RLDS Reformation? Construing the Task of RLDS Theology," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 18, no. 2 (Summer 1985): 92–103; Roger D. Launius, "The RLDS Church and the Decade of Decision," Sunstone 19 (September 1996): 45-55; Roger D. Launius, "Coming of Age? The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in the 1960s," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 28, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 31–57; Roger D. Launius, "Neither Mormon nor Protestant? The Reorganized Church and the Challenge of Identity,” in Mormon Identities in Transition, edited by Douglas Davies (London: Cassell, 1996), 52–60; W. B. "Pat" Spillman, "Dissent and the Future of the Church," in Let Contention Cease: The Dynamics of Dissent in the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, edited by Roger D. Launius and W. B. “Pat” Spillman (Independence, Mo.: Graceland/Park Press, 1991), 259-92.

[3] I deal with this topic in relation to Nauvoo in "The Awesome Responsibility: Joseph Smith III and the Nauvoo Experience,” Western Illinois Regional Studies 11 (Fall 1988): 55–68.

[4] See my explorations of these topics in "The RLDS Church and the Decade of Decision," Sunstone 19 (September 1996): 45–55; and “An Ambivalent Rejection: Baptism for the Dead and the Reorganized Church Experience,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23, no. 2 (Summer 1990): 61–84.

[5] The literature on many Nauvoo theological developments is extensive. For general introductions, see T. Edgar Lyon, "Doctrinal Development of the Church during the Nauvoo Sojourn, 1839-1846," BYU Studies 15 (Summer 1975): 435–46; Marvin S. Hill, "Mormon Religion in Nauvoo: Some Reflections," Utah Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1976): 170–80.

[6] See Richard P. Howard, "The Changing RLDS Response to Mormon Polygamy: A Preliminary Analysis," John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 3 (1983): 14–29; Alma R. Blair, "RLDS Views of Polygamy: Some Historiographical Notes," John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 5 (1985): 16–28; Launius, Joseph Smith III, 190–272; Roger D. Launius, "Methods and Motives: Joseph Smith Ill's Opposition to Polygamy, 1860-90," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 20, no. 4 (Winter 1987): 105–20; Roger D. Launius, "Politicking against Polygamy: Joseph Smith III, the Reorganized Church, and the Politics of the Anti-Polygamy Crusade, 1860-1890," John Whitmer Historical Association 7 (1987): 35–44.

[7] Alma R. Blair, "The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints: Moderate Mormonism," in The Restoration Movement: Essays in Mormon History, edited by F. Mark McKiernan, Alma R. Blair, and Paul M. Edwards (Lawrence, Kans.: Coronado Press, 1973), 207-30; Clare D. Vlahos, "Moderation as a Theological Principle in the Thought of Joseph Smith III," John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 1 (1981): 3-11.

[8] Clare D. Vlahos, "Images of Orthodoxy," in Restoration Studies I, edited by Maurice L. Draper and Clare D. Vlahos (Independence, Mo.: Herald Publishing House, 1980), 184. See also Conrad and Shupe, "An RLDS Reformation?” 92–103; W. Paul Jones, "Demythologizing and Symbolizing the RLDS Tradition," Restoration Studies V, edited by Darlene Caswell (Independence, Mo.: Herald House, 1993), 109–15; Larry W. Conrad, “Dissent among Dissenters: Theological Dimensions of Dissent in the Reorganization," in Let Contention Cease, 199–239.

[9] One may debate whether this is a good thing. W. Grant McMurray criticized several scholars for pointing up the problems of this reformation in his address, "History and Mission in Tension: A View from Both Sides," in Religion and the Challenge of Modernity: The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in the United States Today, edited by Danny L. Jorgensen and Joni Wilson (Binghamton, N.Y.: Global Publications, Academic Studies in the History of Religion, 2001), 229-49. It is a paper filled with his characteristic wit. But more important, it should also be deeply troubling for those who pursue historical knowledge, for it demonstrates serious anti-historical and, in some instances, anti-intellectual attitudes.

[10] Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945). A revised and expanded second edition appeared in 1971.

[11] Donna Hill, Joseph Smith: The First Mormon, (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1977).

[12] Richard Lyman Bushman with the assistance of Jed Woodworth, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005).

[13] Klaus J. Hansen, "The World and the Prophet," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 1, no. 2 (Summer 1966): 106.

[14] Boyd K. Packer, “‘The Mantle is Far, Far Greater than the Intellect,’” BYU Studies 21 (Summer 1981): 262.

[15] Men in Black, feature film, starring Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones (Universal Studios, 1997).

[16] The Holy Scriptures (Independence, Mo.: Herald Publishing House, 1944 ed.), John 18:38.

[post_title] => Is Joseph Smith Relevant to the Community of Christ? [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 39.4 (Winter 2006): 58–67I spoke as a member of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints/Community of Christ. As a result, I had a decidedly different perspective on Joseph Smith than my co-panelists. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => is-joseph-smith-relevant-to-the-community-of-christ [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2024-01-28 19:39:09 [post_modified_gmt] => 2024-01-28 19:39:09 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=10248 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1

The Remnant Church: An RLDS Schismatic Group Finds a Prophet of Joseph's Seed

William D. Russell

Dialogue 38.3 (Fall 2005): 26–54

When the 1984 conference approved Section 156 , which also indicated that the soon-to-be-built temple in Independence would be dedicated to the pursuit of peace, it became clear that the largest “schism”—separation from the unity of the Church—in the history of the RLDS Church was in the making.

When the 1984 conference approved Section 156 , which also indicated that the soon-to-be-built temple in Independence would be dedicated to the pursuit of peace, it became clear that the largest “schism”—separation from the unity of the Church—in the history of the RLDS Church was in the making.

[post_title] => The Remnant Church: An RLDS Schismatic Group Finds a Prophet of Joseph's Seed [post_excerpt] => Dialogue 38.3 (Fall 2005): 26–54When the 1984 conference approved Section 156 , which also indicated that the soon-to-be-built temple in Independence would be dedicated to the pursuit of peace, it became clear that the largest “schism”—separation from the unity of the Church—in the history of the RLDS Church was in the making. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => closed [ping_status] => closed [post_password] => [post_name] => the-remnant-church-an-rlds-schismatic-group-finds-a-prophet-of-josephs-seed [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2023-10-11 21:03:08 [post_modified_gmt] => 2023-10-11 21:03:08 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.dialoguejournal.com/?post_type=dj_articles&p=10416 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => dj_articles [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) 1