Articles/Essays – Volume 42, No. 4

Who was Second Nephi?

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

The story of Nephi occupies a prominent place in the hearts of the Latter-day Saint people. As a young man, he was singularly affected by his father’s teachings and, despite his relative youth, became the de facto leader of the extended families of Lehi and Ishmael even before his father’s death. Later, as a prophet in his own right, he led a people who called themselves “Nephites” in his honor; and nine centuries after his death, hundreds of thousands of Nephites still honored his name and legacy. He belongs to the ages as the namesake of an ancient nation.

Nephi demonstrated his spiritual strength by his willingness to listen to and obey his father’s words, by leading his brothers in their mission to obtain the plates of brass, by returning to invite Ishmael’s family to join them in the wilderness, and in his desire to see Lehi’s vision for himself. He was sufficiently in tune with spiritual things that he received commandments to make records and maintain a history of his family’s experiences. He saw remarkable visions of his people’s future. As Lehi’s family distanced itself from Jerusalem and throughout the long journey to the promised land, Nephi also became a practical leader. He rescued the family from the threat of starvation in the wilderness and then made both the tools and the ship in which they crossed the waters.

From the beginning, Nephi’s older brothers Laman and Lemuel resented his ascendancy. They considered it their right to lead the combined families of Lehi and Ishmael and suspected Nephi of aspiring to make himself their king (1 Ne. 16:38). After Lehi’s death, the leadership issue came to a head. Nephi feared that Laman and Lemuel would kill him; they feared that his leadership ambitions would displace them (2 Ne. 5:3). Nephi avoided the conflict by escaping into the wilderness with those who wanted him as their leader. Eventually, those followers came to look upon him as “a king or a protector” by about 559 B.C. (2 Ne. 6:2).

Beyond this, the Book of Mormon tells us almost nothing about Nephi’s twenty-five-year reign. The text never refers to him by any title suggesting kingship, although the book of First Nephi is subtitled “his reign and ministry.” When Nephi “saw that he must soon die,” he chose a successor. Jacob describes the event in these words:

Wherefore, he anointed a man to be a king and a ruler over his people now, according to the reigns of the kings.

The people having loved Nephi exceedingly, he having been a great protector for them, having wielded the sword of Laban in their defense, and having labored in all his days for their welfare—

Wherefore, the people were desirous to retain in remembrance his name. And whoso should reign in his stead were called by the people second Nephi, third Nephi, and so forth, according to the reigns of the kings; and thus were they called by the people, let them be of whatever name they would.

And it came to pass that Nephi died.

Now the people which were not Lamanites were Nephites; nevertheless, they were called Nephites, Jacobites, Josephites, Zoramites, Lamanites, Lemuelites and Ishmaelites. (Jacob 1:9-13)

Perplexingly, in these five simple verses Jacob listed the names of all the Nephite and Lamanite tribes except Sam’s, but does not name Nephi’s successor, whom he refers to only as “second Nephi.” These omissions are strange for a people who kept not one, but two sets of records, a primary purpose of which was to keep their genealogy. Furthermore, this family was so small that its principal members could be counted on one hand. Jacob’s curious failure to identify Nephi’s successor leaves “second Nephi’s” identity ripe for examination. Based on some reasonable deductions from other evidence in the text, I suggest that Sam, or perhaps Sam’s son, was the most likely candidate. If so, then successive kings may well have also been Sam’s descendants, leading the entire Nephite nation from Nephi’s death until the beginning of the reign of the judges. Though not conclusive, the case for Sam as second Nephi is at least reasonable, and seems more likely to me than any other possibility.

Who Are the Candidates?

The field of likely candidates begins with Nephi’s own list of the men who accompanied him when he escaped into the wilder ness: “I, Nephi, did take my family, and also Zoram and his family, and Sam, mine elder brother and his family, and Jacob and Joseph, my younger brethren, and also my sisters, and all those who would go with me” (2 Ne. 5:6). From this list, Zoram, Sam, Jacob, and Joseph are the most likely candidates, as they are the only adults mentioned. A son of Nephi may also be in the mix. However, some of these candidates seem more likely than others.

Nephi’s son: Nephi married one of the daughters of Ishmael (1 Ne. 16:7), and took his “family” with him when they parted from the Lamanites (2 Ne. 5:6). He mentions his “children” once (1 Ne. 18:19), and Lehi refers to his “seed” (2 Ne. 4:11), but there is no explicit mention of a son. One is left to wonder whether Nephi had a son. It is interesting that Nephi gave the small plates to Jacob, with instructions to pass them down to his own posterity (Jacob 1:1-8). Nephi is not likely to have given his records to a brother if he had a worthy son who could have taken custody of them. Taken together, these references suggest that Nephi either lacked a worthy son or lacked a male heir altogether.

Zoram: Formerly Laban’s servant, Zoram unwittingly helped Nephi obtain the plates of Laban, then joined Lehi’s family and followed them into the wilderness. Lehi considered him a “true friend unto . . . Nephi, forever,” who had “been faithful” up through the time of Lehi’s death (2 Ne. 1:30-31). John W. Welch argues that Zoram may have been adopted into Lehi’s family and thus had the same rights as Lehi’s other sons. Zoram married Ishmael’s eldest daughter (1 Ne. 16:7), suggesting that he may have been older than all of Lehi’s sons. Even assuming that Zoram was worthy and had been adopted into Lehi’s family, the possibility that he was older suggests that he may have predeceased Nephi.

Sam: From the beginning of Nephi’s history, he recorded both his own belief in Lehi’s words and Sam’s belief in his words (1 Ne. 2:17). Nephi wrote that Laman and Lemuel rebelled “against me, Nephi, and Sam” (1 Ne. 7:6). When Lehi related his vision of the tree of life, he had “reason to rejoice in the Lord because of Nephi and Sam” (1 Ne. 8:3). All of the textual evidence places Sam consistently and faithfully at Nephi’s side. Sam was older than Nephi and may have had the same leadership right that Laman and Lemuel claimed by virtue of their age. He may also have predeceased Nephi, but still seems like a good candidate otherwise.

Jacob and Joseph: Nephi’s younger brothers held the priestly office during his life (2 Ne. 5:26) and continued as spiritual leaders after his death (Jacob 1:18). Jacob inherited Nephi’s small plates pertaining to spiritual things, continued making the record, and handed them on to his son, according to Nephi’s direction (Jacob l:l-2). Jacob’s (and presumably Joseph’s) service in the priesthood began about 559 B.C. (2 Ne. 5:26), at least fifteen years before Nephi’s death (2 Ne 5:34; Jacob 1:1). Both continued their ministry after Nephi’s death, and Jacob’s record shows that he preached with confidence and authority. Jacob’s report that the people became wicked “under the reign of the second king” also suggests that “second Nephi’ was someone other than himself (Jacob 1:15).

Joseph, also a priest and teacher, was the youngest of Lehi’s sons. He appears in the textual record primarily as Jacob’s associate in the ministry. His youth and his apparent continuing service in the ministry suggest that his succession claim was the weakest.

Based on this brief overview, it is possible to reach some preliminary conclusions about the relative merits of these candidates. Jacob and Joseph seem the least likely because of their youth (older brothers would likely have had a superior claim) and their well-documented and continuing service as priests and teachers. Jacob had the small plates but does not mention the large plates, which were held by the kings. He also fails to identify himself as the second king in the records he kept, although he could easily have done so.

Nephi’s son would be a logical candidate in a patriarchal society, but also seems unlikely. The text does not mention a son, and Nephi delivers the small plates to his brother Jacob. It appears that either Nephi had no son or, for unknown reasons, his son was not the successor.

Zoram, a faithful and supportive friend, also seems unlikely. He was not a literal member of the family, although he may have been adopted; and he may have been enough older that he predeceased Nephi.

This preliminary evaluation of the candidates suggests that Sam was the most likely choice. Although he was slightly older than Nephi, he was clearly a spiritual companion, perhaps a peer. Each of the other candidates simply seems less likely than Sam.

Rules for Succession

The mystery of Nephi’s successor results from Jacob’s curious failure to identify the second king when he could easily have done so. In this small and close-knit family, Jacob surely knew the successor’s name, yet he wrote only that Nephi anointed “a man” to succeed him. His brief description of the exchange of power, however, suggests what may have been a rule of succession. By mentioning that the anointing occurred “according to the reigns of the kings” (Jacob 1:9), Jacob seems to suggest that the succession followed a well-established and familiar pattern. Since he was recording the first Nephite succession, a likely source for a familiar pattern would have been the succession of Israelite kings, recorded on the brass plates, even though Jacob was born after the family left Jerusalem. For at least the previous century, the Israelite kings had usually passed their crowns to their sons.

Other Book of Mormon personalities also allude to the rules under which they expected successions to occur. Laman and Lemuel complained that “it belongs unto us, who are the elder brethren, to rule over this people” (2 Ne 5:3; see also 1 Ne. 16:37, Mosiah 10:15). Interestingly, both older sons considered their right superior to Nephi’s. Five hundred years later, Ammoron argued that the first Nephites “did rob their brethren of their right to the government, when it rightly belonged to them” (Alma 54:17). Mosiah acknowledged that the throne “rightly belong[ed]” to one of his sons, apparently the eldest (Mosiah 29:l-6). After Pahoran’s death, “there began to be a serious contention concerning who should have the judgment seat among… the sons of Pahoran” (Hel. 1:2). When the contention resulted in the deaths of all Pahoran’s sons, there was “no one to fill the judgment seat” (Hel 2:1-2). These statements are consistent with Jacob’s comment and seem to reflect a common expectation of father-to-oldest-son succession.

In addition to these expressions of expectations, the Book of Mormon contains descriptions of three Nephite patterns of succession that offer insights into how the Nephites actually chose successors for leadership offices.

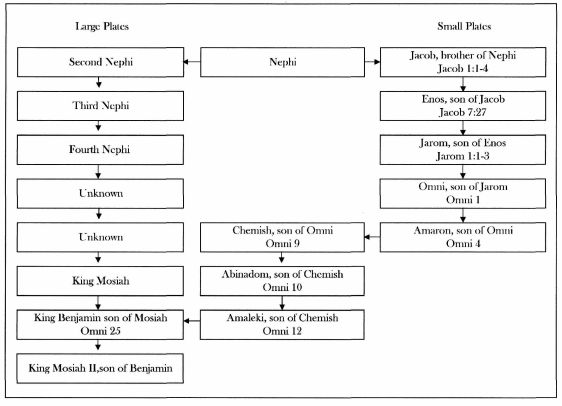

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1: Custodians of the Large and Small Plates of Nephi, see PDF below, p. 6]

The first part of the pattern is the list of custodians of the small plates of Nephi. Though not a pattern of succession to the “throne,” it records names and relationships. Nephi established this pattern by giving the small plates to Jacob, with instructions to pass them “down unto Jacob’s seed, from generation to generation” (Jacob 1:5). This pattern held for seven generations, each record-keeper inscribing his name and the fact that he was transmitting the plates to his son. (See Table 1).

From Jacob onward, the plates were passed from father to son until Amaleki gave them to King Benjamin because he “had no seed” and no brother (Omni 1:25, 30). “From generation to generation” apparently meant “from father to son” to Jacob and his descendants, as that was the practice they followed. Amaleki deviated from the pattern for the same reason that Nephi gave the plates to Jacob: no successor of his own.

The Book of Mormon does not record the name of the recipient of Nephi’s large plates upon his death, but we may surmise something about his identity. After receiving the small plates from Amaleki, King Benjamin placed them with “the other” plates of Nephi, which were “had among the kings, from generation to generation, until the days of king Benjamin” (W of M 1:10-11; see also Jarom 1:14, Omni 1:11). Assuming that “from generation to generation” had the same father-to-son meaning for the large plates as for the small, then Benjamin’s ancestors were arguably the custodians of the large plates and can be traced backwards, son-to-father, to Nephi II, the second Nephite king. Therefore, one of King Mosiah’s ancestors was arguably Nephi II, who received the large plates from Nephi at the time of his death.

The second part of the pattern belongs to the three named Nephite kings: Mosiah I, Benjamin, and Mosiah II, a chain of fathers and sons. Benjamin, who received the small plates from the childless Amaleki, also received the kingdom, the large plates, the plates of brass, the sword of Laban, and the Liahona from his father, Mosiah I, and delivered both to his own son, Mosiah II (Mosiah 1:15-16). These three kings also followed the expected pattern until Mosiah II found himself without a successor: he had four worthy sons who all refused to be king. I hypothesize that Ammon is the eldest and that Aaron is the second eldest (Mosiah 27:34; Alma 17:18). When Ammon refused and the voice of the people chose Aaron, Mosiah became concerned about possible resentment from the son “to whom the kingdom doth rightly be long” (Mosiah 29:6), apparently Ammon, who might later reclaim his rightful place and create a conflict among the people (Mosiah 29:26-27).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2: The Twelve Nephite Chief Judges, see PDF below, p. 8]

Mosiah sidestepped the succession problem by instituting the system of judges (Mosiah 29:25). Although the chief judges were not “kings,” they occupied the position of supreme political leadership as the kings had done. Thus, their pattern of succession should further inform our understanding of Nephite expectations of succession. (See Table 2.)

As summarized in Table 2, each chief judge followed the familiar pattern: delivering the judgment seat to his son, unless some circumstance intervened. Whenever the succession was from father to son, the record says so; whenever there was a deviation, the record explains why. The most common reasons for chief judge deviations include the lack of a son, a son’s desire to devote himself to preaching, and the chief judge’s murder.

In short, these three patterns suggest that Nephite successions occurred under the following “rules,” which, I suggest can also be applied to Nephi and his successor:

1. There is a strong preference, often characterized as a “right,” for father-to-son succession.

2. When Rule 1 is followed, Book of Mormon record-keepers consistently state that the successor is the son.

3. Whenever there is a deviation from Rule 1, the record-keepers consistently explain why.

4. The eldest son seems to have had first claim, followed by other sons in order of birth.

The Succession of Second Nephi

Applying these rules to the succession between Nephi and “Second Nephi” suggests that Nephi should have passed the kingdom to his son. However, the record fails to mention that Nephi II was Nephi’s son, thus violating Rule 2. Jacob’s failure to record his nephew’s name suggests a deviation that required an explanation (Rule 3). Might Jacob’s long but ambiguous report be such an explanation?:

Now Nephi began to be old, and he saw that he must soon die; therefore he anointed a man to be a king and a ruler over his people now, according to the reigns of the kings.

The people having loved Nephi exceedingly, he having been a great protector for them, having wielded the sword of Laban in their defense and having labored in all his days for their welfare—

Wherefore, the people were desirous to retain in remembrance his name. And whoso should reign in his name were called by the name of second Nephi, third Nephi and so forth, according to the reigns of the kings; and thus they were called by the people, let them be of whatever name they would.

And it came to pass that Nephi died.

Now the people which were not Lamanites were Nephites; nevertheless they were called Nephites, Jacobites, Josephites, Zoramites, Lamanites, Lemuelites and Ishmaelites. (Jacob 1:9-13)

Later record-keepers straightforwardly explained deviations as flowing from the lack of a son or a clear abdication. Yet for unspecified reasons, Jacob layered two facts onto this succession. First, Nephi’s successors would be called “second Nephi,” “third Nephi,” etc. Second, Jacob here listed the Nephite “tribes,” which, also for unspecified reasons, did not include “Samites” (Jacob 1:13). I hypothesize that either or both of these might explain the deviation from Rule 1.

Interestingly, Jacob’s phrase, “anointed a man to be a king and a ruler over his people,” resembles the descriptions of three other known deviations from the father-to-son pattern. When Alma the younger left the judgment seat to preach the gospel, he “selected a wise man” to succeed him, without mentioning his relationship to Alma (Alma 4:16). Helaman “was appointed” to fill the judgment seat when “there was no one to fill” it after Pacumeni’s death (Hel. 2:1-2). And when Helaman’s son Nephi (number 7 on Table 2) decided to devote himself to preaching, he “delivered up the judgment seat to a man,” later identified as Cezoram, again with no indication of any kinship (Hel 5:1-5). Thus, Jacob’s choice of the phrase “anointed a man to be a king and a ruler” may actually be a subtle indication that the second king was not Nephi’s son. In light of Nephi’s delivery of the small plates and spiritual leadership to one brother, the most likely choice for the large plates and the kingdom might well have been another brother. Since Jacob and Joseph are considered unlikely candidates, what about Sam?

Lehi’s Blessing

As Lehi approached death, he gathered his extended family to receive his final words of instruction and blessing. Beginning with Laman and Lemuel, Lehi chastised them for a long list of shortcomings, urging them to repent and to “rebel no more against your brother” (2 Ne 1:1-29). To all of his sons and to Ishmael’s sons, he promises his first blessing if they will follow Nephi (2 Ne.l:28). Lehi next blesses Zoram (2 Ne. 1:30-31), Jacob (2 Ne. 2), Joseph (2 Ne. 3), Laman’s children (2 Ne. 4:3-8), Lemuel’s children (2 Ne. 4:9), and Ishmael’s sons and household (2 Ne. 4:10). Despite Sam’s apparently exemplary record of obedience, his blessing comes last—even after Lehi’s blessings on the children of the rebellious Laman, Lemuel, and sons of Ishmael.

And after he had made an end of speaking to them, he spake unto Sam, saying: Blessed art thou, and they seed; for thou shalt inherit the land like unto thy brother Nephi. And thy seed shall be numbered with his seed; and thou shalt be even like unto thy brother, and thy seed shall be like unto his seed; and thou shalt be blessed in all thy days.

And it came to pass that after my father, Lehi, had spoken unto all his household, according to the feelings of his heart and the Spirit of the Lord which was in him, he waxed old. And it came to pass that he died, and was buried. (2 Ne. 4:11,12; emphasis mine)

Lehi’s choice of Sam as the recipient of his last recorded words in life endowed them with momentous significance. Not only would Sam’s seed be “like unto” and “numbered with” Nephi’s posterity, but Sam would be “like unto” Nephi. This language suggests both the inclusion of Sam and his posterity among Nephi’s descendants and also a personal status or work for Sam that is comparable to Nephi’s. I argue that this blessing may even include Nephite leadership. In other words, on the basis of Lehi’s blessing, Sam may no longer be Nephi’s brother, but his adopted son. As such, Sam and his heirs would thus satisfy the description in Mosiah 25:13, that “the kingdom had been conferred upon none but those who were descendants of Nephi.”

Did Sam Succeed Nephi?

To summarize the discussion to this point, the Book of Mormon text, though not naming Nephi’s successor, suggests four rules for succession, contains a list of likely candidates, some of whom are more likely than others, and reports a blessing on Sam. That blessing apparently adopts Sam and his posterity into Nephi’s family and confers upon him a status like Nephi’s—a status compatible with kingship.

In addition, Jacob’s description of the succession contains parallels with Lehi’s blessing. Lehi’s last recorded words were spoken to Sam. Nephi’s last recorded words were spoken to his successor. They were words of anointing and perhaps blessing, and were arguably also spoken to Sam. Jacob immediately thereafter reports that future kings will be called “Nephi” and lists Nephite tribes, a list that omits Sam. Thus, in three conveniently juxtaposed verses de scribing the succession of the Nephite king, Jacob reports that some unnamed “man,” important and worthy enough to succeed Nephi as king has done so, taken the name “second Nephi,” and omits Sam and his posterity from future Nephite history, despite Sam’s faithful support of Nephi from the outset.

From these clues, I argue that Sam has succeeded Nephi as king, and will hereafter be known as “second Nephi.” The “Samites” are therefore not missing at all. They have simply become Nephites. While this argument for Sam as second Nephi is not conclusive, it is persuasive and reasonable. If Sam was the second Nephite king, then successive kings were Sam’s descendants, keeping the large plates that the kings passed down “from generation to generation.” Just as the small plates included the genealogy of Jacob’s line, the large plates likely recorded the names of the Nephite kings from Nephi II to Mosiah I. Sam and his sons would also have possessed the Liahona, the sword of Laban, and the brass plates from Nephi’s death until the reign of the judges (Mosiah 1:16). When Amaleki conferred the small plates on king Benjamin (Omni 1:25), Sam’s distant descendant became the first of Lehi’s descendants since Nephi to unite both spiritual and secular functions. He possessed all of their treasures and all of their records, and “like unto Nephi” was their prophet, priest, and king.

Jacob’s grandson wrote: “Our kings and our leaders were mighty men in the faith of the Lord” (Jarom 1:7). This characterization is demonstrably true of Nephi, Jacob, Mosiah I, Benjamin, and Mosiah II. I argue that it can appropriately be applied to Sam. Hundreds of years later with all of the Nephite records before him, Mormon characterized Sam as a “just and holy” man along with Nephi, Jacob, and Joseph (Alma 3:6). In our day, President Howard W. Hunter declared that Sam “ultimately received the same blessings promised to Nephi and his posterity. Nothing promised to Nephi was withheld from the faithful Sam, yet we know very little of the details of Sam’s service and contribution. He was an almost unknown person in life; but he is obviously a triumphant leader and victor in the annals of eternity.” If Sam was in fact Nephi II, it may be that he was both a triumphant leader in the annals of eternity and the leader of the Nephites in life.

Summary

The case for Sam as second king of the Nephites is not beyond challenge. Because the Book of Mormon does not name Nephi’s successor, the second king’s identity will always remain somewhat speculative. However, after excluding Jacob and Joseph because of their ongoing religious roles, Zoram and Sam are the only other adult males in the company worthy of being mentioned in the narrative. Sam seems to be the more likely candidate for the following reasons: (1) Lehi’s powerful blessing predicts a significant role for him; (2) That role is consistent with the otherwise un explained absence of “Samites” from the record; (3) Sam’s apparent adoption into Nephi’s household as his son fits the long-standing practice of passing high offices from father to son. Although other Book of Mormon scholars have argued for such an adoption, they have not suggested a reason for it; (4) Such an adoption would provide Nephi with an heir—a possibility since the text does not mention Nephi’s son; (5) Sam’s native goodness and virtue are consistent with what is known of other Nephite kings; and (6) The symmetry of the arrangement is appealing: Nephi gave the spiritual leadership and the small plates to Jacob, the kingdom and the large plates to Sam. Jacob would succeed him as priest, and Sam as king.

Jacob’s reason for omitting Nephi II’s identity remains a mystery. Even so, there is enough evidence in the Book of Mormon from which to hypothesize that Sam (or perhaps Sam’s son) was that successor. Lehi’s promised blessing, that Sam would be “like unto Nephi” and “blessed in all his days,” would be amply fulfilled in this way.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue