Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 1

Variety of Perceptions of God Among Latter-day Saints

In their 2010 book America’s Four Gods: What We Say About God—And What That Says About Us, sociologists of religion Paul Froese and Christopher Bader argue that Americans harbor four conceptualizations of God.[1] These conceptualizations sit on two axes: the degree to which God is involved in the world and the degree to which God judges the sinner. Put together, these four quadrants include the so-called “authoritative God” (who is active in the world and judgmental of the sinner), the “benevolent God” (who is active in the world but less judging of the sinner), the “critical God” (who is less involved in the world but nevertheless judgmental of the sinner), and the “distant God” (who is neither involved in the world or judging of the sinner).[2] These four ideas of God do not always evenly match up with a particular denomination. For instance, as Froese and Bader argue, Roman Catholics are just as likely to believe in the so-called “authoritative God” as they are the “benevolent God.”[3] This suggests that understanding the subtle nuance of a practitioner’s belief should go far beyond simply evaluating whether or not they attend a certain church and suggesting further that two attendees at the same church service may be speaking together about “God” while unknowingly possessing two varying conceptualizations.[4]

The present study is a small-scale replication of Froese and Bader’s method within the Latter-day Saint community, a group neglected in their initial research. There is within this community the (possible) theological justification for any of these four models of the divine. For instance, Latter-day Saints seem to harbor a certain ambivalence regarding the extent to which God is involved in the world. On one hand, Latter-day Saints affirm the theophanies of their founder Joseph Smith Jr., suggesting their belief in a god who is capable and willing to participate in revelatory visitations.[5] Additionally, Latter-day Saints place continual and repeated emphasis on the influence of the Holy Spirit in their life as a guide and prompter. The Holy Spirit, acting as an emissary from God, is sometimes referred to as a “constant companion” for the baptized and has been cited as warning of danger, comforting, and passing on communication from God.[6] On the other hand, Latter-day Saints also stress the role of agency in human life and God’s unwillingness—or perhaps even inability—to interfere in one’s life non-consensually. As one Latter-day Saint hymn puts it, “For this eternal truth is giv’n: That God will force no man to heav’n.”[7] Terryl and Fiona Givens describe a God “who weeps” because he (God is gendered male in Latter-day Saint thought) is unable to change his children’s ways and, more to the point, experiences vulnerability because of this limitation.[8] In other words, Latter-day Saint theology would postulate (in contrast to Calvin’s irresistible grace) that, for them, God is met and experienced on the believer’s terms rather than God’s, suggesting that perhaps Latter-day Saints might understand God as being less involved. Thus, it is in the interest of scholars to ascertain how these varying factors come together to create the Latter-day Saints’ understandings of God.

The present study was interested not only in what sort of God LDS people believed in but what type of variation might be found within the community. To that end, active LDS men and women, LGBT members of the Church, and former members were polled and interviewed. Each section in the paper addresses one of these subgroups of respondents. In summary, the following was found:

- Generally, members of the LDS Church believe in the “benevolent God,” stressing God’s love and involvement.[9]

- In keeping with national trends, LDS women believe God to be more loving (less judgmental) than Mormon men.

- There was a positive relationship between church activity and belief in the “benevolent God.”[10] As church activity increases, belief in God’s involvement and love also increases.

- There is a positive relationship between belief in LDS doctrines and belief in a benevolent God.

- There is a positive relationship between a feeling of community in one’s local congregation and belief in a benevolent God.

- Non-LGBT members of the Church tend to believe God is more involved and loving (non-judgmental) than LGBT members do.

- LGBT members are more likely to describe God as “critical,” but those who attend church regularly still reported God as loving and involved.

- Former members of the Church have previously believed in the “benevolent God.”[11]

- Former members of the Church feel their experiences in the Church cut against their understanding of a deity who is both involved and loving.

Description of Survey and Interviews

The survey I administered asked the same questions with the same scale as Froese and Bader asked originally, but it was expanded to include questions unique to the Latter-day Saint experience. These additional questions included inquiries regarding the rate at which participants attended church meetings, the frequency with which they paid tithing, and their level of belief in Latter-day Saint doctrine. It also asked for participants to rate the extent to which they believed Joseph Smith was a prophet as well as the extent to which he was a role model. Lastly, the survey included additional questions meant to gauge the extent to which the respondent considered themselves a member of the Latter-day Saint community, including a question regarding the extent to which they “fit in” with the Latter-day Saint community and another asking the extent to which they are “similar to” other Latter-day Saints.

Each semi-structured interview began with me asking the same questions asked by Froese and Bader. These questions included:

- Do you believe in God? [If not, do you believe that something exists beyond our physical world?]

- Please describe God as best you can. [Is God a “he” or a “she”? What does God look like? Can you describe God’s personality?]

- Is God active in your daily life? In what ways?

- Are there specific things that you have experienced that you believe were acts of God?

- Are there world events that you believe were acts of God?

- How does God deal with sinners?

- Is there divine justice? What is it and how is it accomplished?

- Does God have an opinion about moral issues? [e.g., abortion, homosexuality, the death penalty]

The second half of the interview was rather unstructured, beginning with my simply saying, “Tell me about your experience in the Latter-day Saint community.” In most cases, this request was sufficient to prod data regarding the extent to which the participant felt like a valued member of the organization. Each interview lasted roughly forty-five minutes, and each was transcribed and thematically coded. The respondents were also asked for basic demographic information including their gender, age, place of residence, sexual orientation, and race.

This study does not argue itself to be conclusive and there are obvious limitations to the research conducted. The link to the survey was distributed primarily via social media, especially Facebook and Twitter. As such the respondents tended to be under the age of forty. In addition, most of the survey respondents were female. After some interview participants were identified using social media, a snowball approach was employed to find subsequent participants. This study attempted to collect a stratified sample for interviews based on the demographic ratios existing within the Latter-day Saint population. This proved problematic on at least two fronts. For the study it was assumed, as some sources have suggested, that 60 percent of Latter-day Saints are, as they would say, inactive, meaning they no longer attend church regularly.[12] In addition, in a true stratified sample, there would have been only one or two interviews conducted with LGBT Latter-day Saints. However, in order to gain greater representation, that particular demographic was expanded. The study also assumed that Latter-day Saint women outnumber Latter-day Saint men at a rate of 6:4, as has been reported by the Pew Research Center. This sample is not statistically representative of Latter-day Saints as a whole because most of the survey respondents were female. Note also that the names of all interviewed participants have been changed.

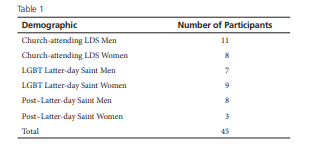

With these assumptions in place, the final sample group for interviews can be viewed in table 1.

| Demographic | Number of Participants |

| Church-attending LDS Men | 11 |

| Church-attending LDS Women | 8 |

| LGBT Latter-day Saint Men | 7 |

| LGBT Latter-day Saint Women | 9 |

| Post–Latter-day Saint Men | 8 |

| Post–Latter-day Saint Women | 3 |

| Total | 45 |

A Loving Heavenly Father: A Look at Latter-day Saints Generally

Overwhelmingly, church-attending Latter-day Saints believe in a “benevolent God”: a God who is involved in the world but not angry or judging of the sinner.[13] Latter-day Saints who regularly attend church rank God’s love highly and his critical and wrathful nature very low. The clear majority either agree or strongly agree that God is ever-present and either disagree or strongly disagree that distant is an appropriate classifier for deity. In short, the Latter-day Saints believe in a God who is both benevolent and helpful.

Survey Data

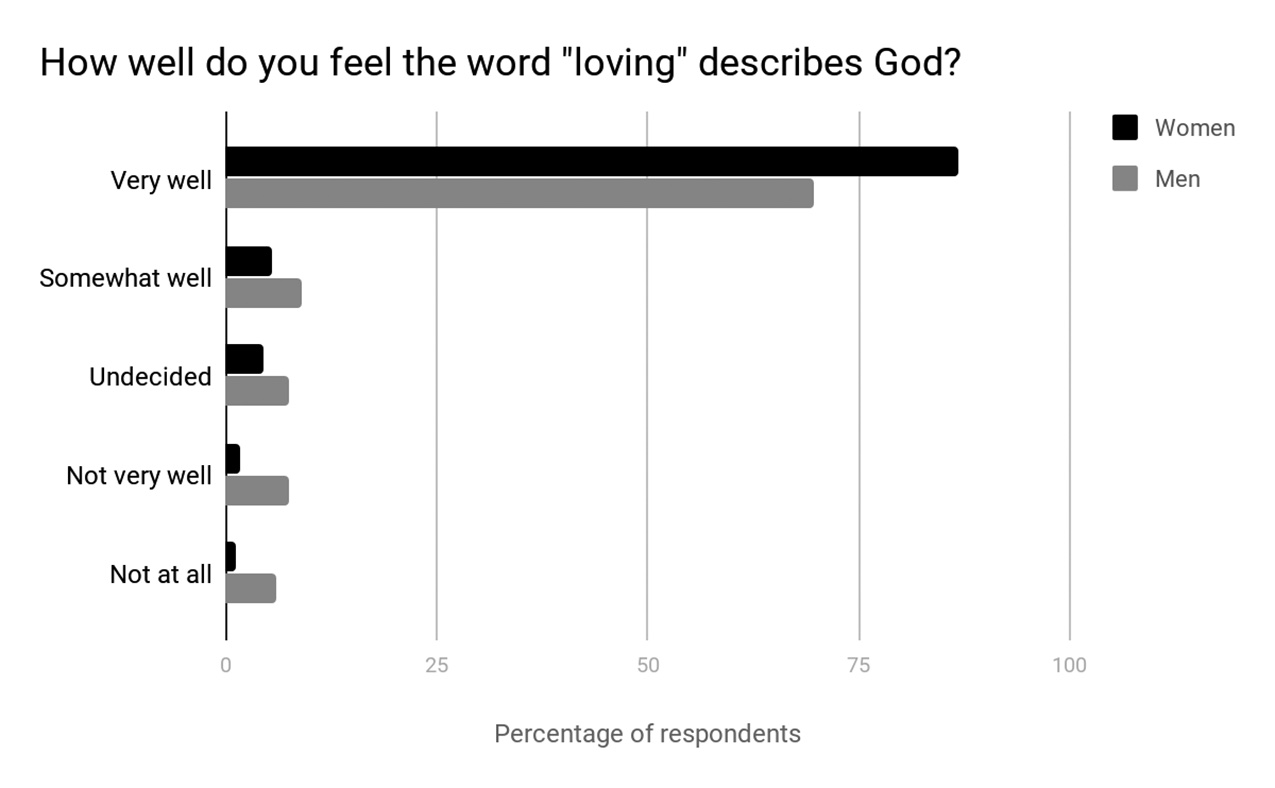

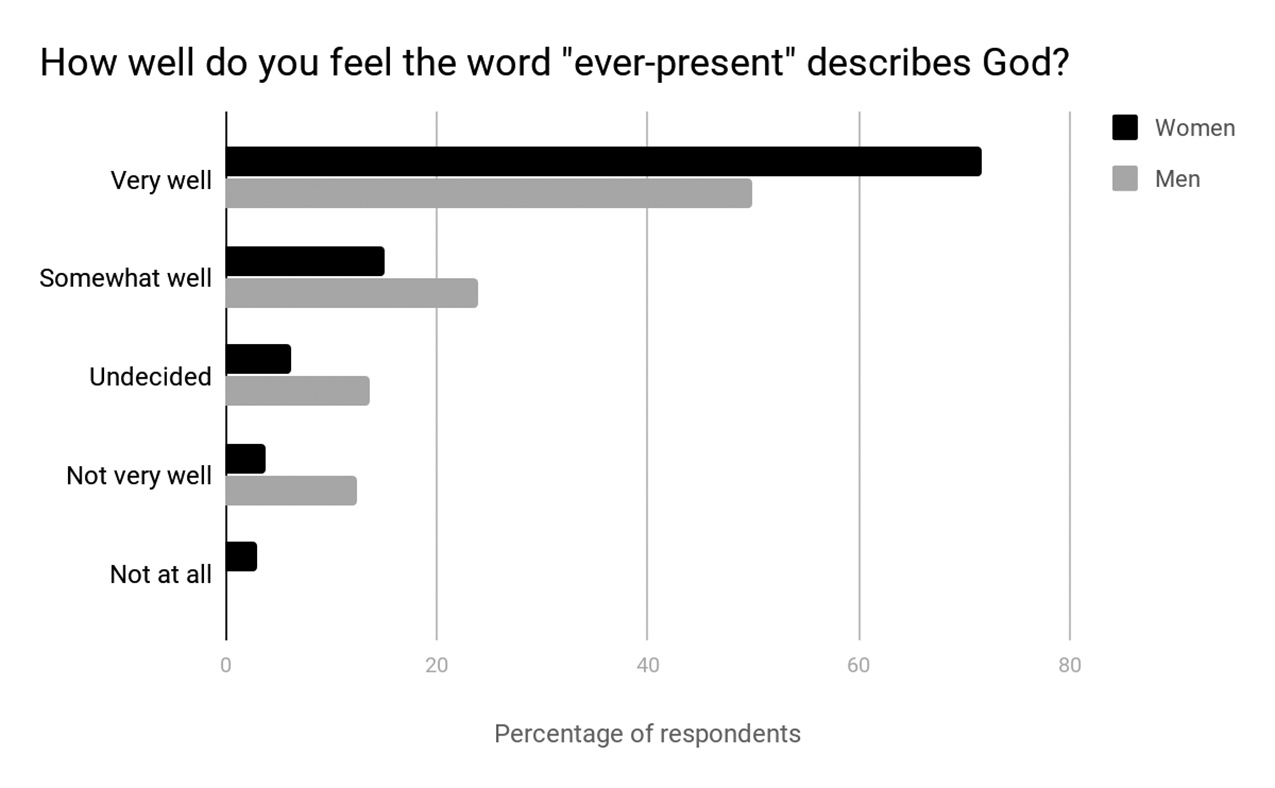

Looking at the survey data, there are some interesting disparities between genders. My survey found that Latter-day Saint women view God as more involved and more loving than do their male counterparts. This is not necessarily a surprising finding. Froese and Bader also found that women, on average, tend to lean toward the “benevolent God,” who is both highly involved and highly loving.[14] Additionally, Latter-day Saint women are more likely than men to believe God is involved. For instance, 71 percent of women reported that the term ever-present describes God very well. This is compared to just over half of Latter-day Saint men who reported the same.

The data suggest that belief in a loving Latter-day Saint God is correlated with belief in Latter-day Saint teachings, activity in the Church, and social stability within the organization. Whenever any of those three indicators rise, the respondents’ belief in a loving God seems to rise in turn. For instance, 99 percent of respondents who agreed that Joseph Smith was a prophet also found God to be loving.[15] In contrast, only 48 percent of those who either strongly disagreed or disagreed that Joseph Smith was a prophet felt that God was loving. The same trend can be seen when one does not believe Joseph Smith to have been a good role model or that the current Church leadership receives revelation.

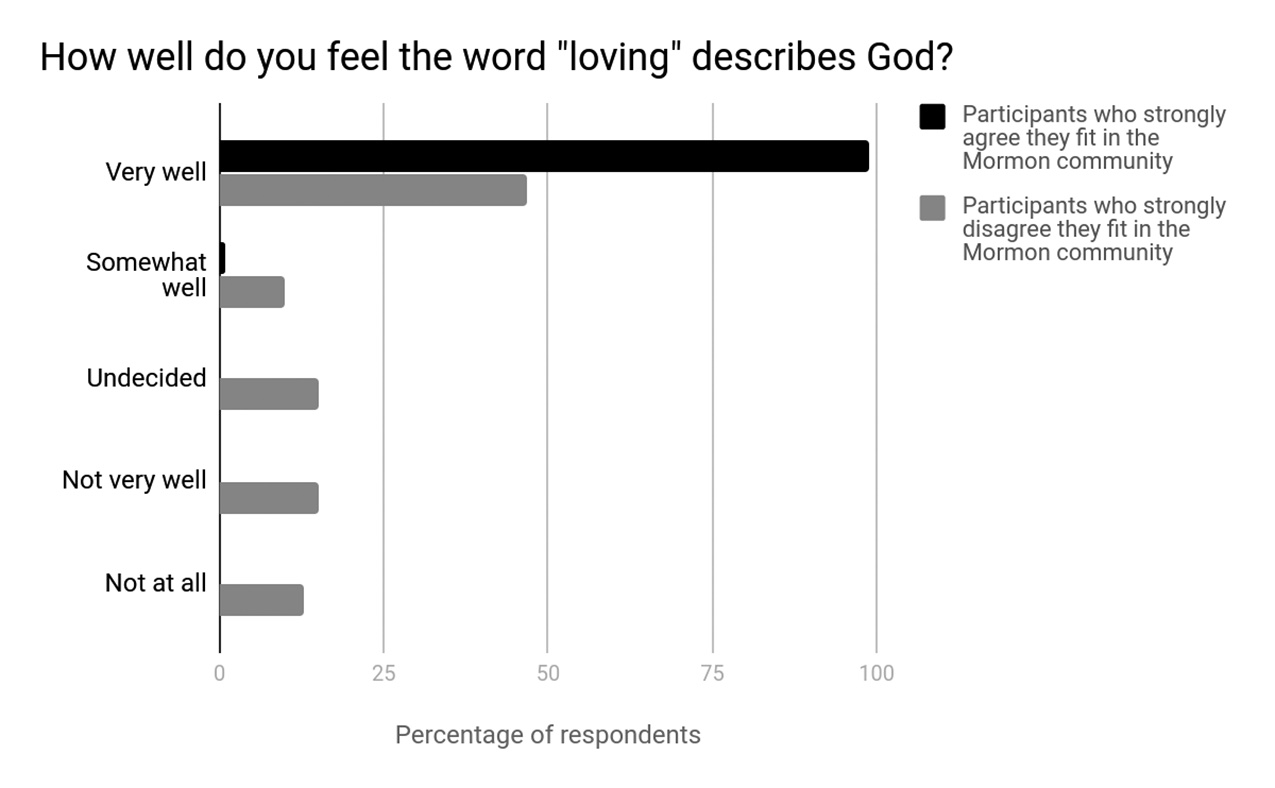

Perhaps most striking, when respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “The majority of Latter-day Saints are similar to me,” they reported believing in a loving God at 97 percent. However, the same can only be said of 78 percent of respondents who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. A similar trend is found in response to the statement “I ‘fit’ in the Latter-day Saint community.” More than 98 percent of respondents who strongly agreed with that statement also reported that loving described God very well. However, only 47 percent of those who strongly disagreed that they fit in the Mormon community said the same. In other words, simply not fitting into one’s congregation seems to find a correlation with the love they perceive—or don’t perceive—from deity.

Interview Data

Furthermore, Latter-day Saints believed that when God’s presence was not felt regularly, it was likely due to their own lack of trying. More than one interviewee stated so explicitly. “I haven’t felt God in my life . . . because I haven’t been doing what I need to feel God,” said one, typical of the wider trend. In other words, even if God did at points feel distant to Latter-day Saints, the situation was not irreconcilably so. God could be brought back into full high involvement in an individual’s life if they performed religious duties (e.g., reading Latter-day Saint scripture, saying a prayer, church attendance, etc.). Some participants took this further. It wasn’t that God became less involved necessarily, some reported back—rather, when Latter-day Saints were not engaged in religious behaviors, they were, as they stated, less likely to notice God’s acts in their lives. In other words, the “benevolent God” was still loving them and highly involved in their lives, they just didn’t see it.

For Latter-day Saints, there might be scriptural, historical, or theological justification for a harsh, judging God. However, this does not seem to factor into Latter-day Saints’ lived religious experiences with deity. God’s benevolence continues to the point that he doesn’t personally inflict punishment. One respondent, typical of wider trends, describes divine punishment by making a comparison between the effects of sin and the law of gravity. He explained:

Is God himself bringing down a hammer? Oh my goodness, you lied to your mother, you did some unpardonable sin, you need to be punished for that—I don’t think so. I think there are divine laws set in place, and if you go against those laws, then there is justice. So that’s the same things as gravity. . . . If you jump off a cliff, you’re going to be punished for it. I don’t think it’s technically God; it was God that invented gravity, but it was still your fault if you’re stupid enough to jump off a cliff.

Joleen, an active Latter-day Saint living in the Philadelphia area, is a good example.

I asked, “Does God inflict punishment?”

“I don’t know. . . . I don’t think so,” she replied.

I asked her to explain her thinking.

“I mean, in the Book of Mormon, like, there are people who clearly are not doing the right things and clearly, they’re despised tons and it’s clear that it’s a result of their wickedness, but . . . So, I guess that, like, doctrinally, I would say yes. But I don’t know.”

This anecdote illustrates the reluctance of a Latter-day Saint woman to believe in God’s willingness to inflict punishment. Significantly, Joleen realized that what she nominally believed about God was at odds with her experience with God. God, as she experienced him, was too benevolent to inflict punishment, despite his doing so in the scripture she believed in. The question of God’s punishing was cognitively dissonant for her and remained unresolved. This idea, of sin being its own punishment, was a nearly universal response to this question. In short, in widely held Latter-day Saint belief, God doesn’t punish you for your sins—your sins punish you for your sins; God is too benevolent to do it.

The church-attending Latter-day Saint can conceptualize a more loving, more involved God than other demographics that will be discussed. For the church-attending Latter-day Saint, there are not the same obstacles disabling their belief in such an involved figure, in contrast to other demographics. For LGBT Latter-day Saints as well as post–Latter-day Saints, there is a cognitive cost to believing in high levels of God’s involvement. While those who attend church can maximize their benefit by believing in their highly loving and highly involved deity, other types of Latter-day Saints minimize these costs and increase their cognitive benefit by adapting God to the needs of their individual identity.

LGBT Mormons

This section discusses the data surrounding the LGBT Latter-day Saint community. It explores not only what kind of God LGBT Latter-day Saints believe in but also how that understanding of God keeps them involved in a church that would mark any of their romantic relationships as an act of sin. The sample size from which this section pulls is small. As such, in this section I seek only to make claims regarding those polled, not LGBT Mormons generally.

Survey Data

The LGBT Latter-day Saints polled are less likely to identify as believing Mormons. Remaining in the denomination is no easy task given the belief in the sinful nature of sex outside of a heterosexual marriage. Remaining a Latter-day Saint as an LGBT person often means living a life of celibacy. These high demands are likely the reason that the percentage of LGBT respondents who strongly agree that they are believing Latter-day Saints drops nearly in half: 30 percent of LGBT Latter-day Saints compared to 65 percent of heterosexual Latter-day Saints.

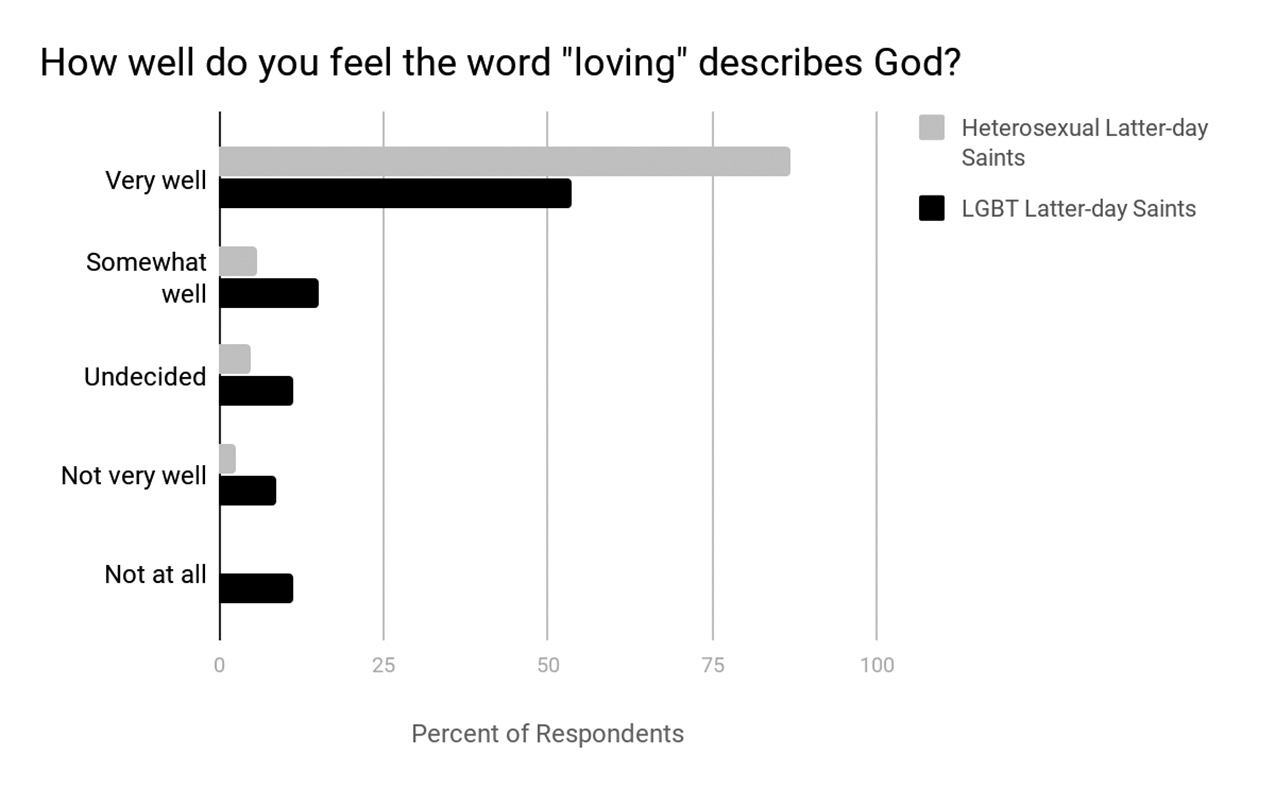

Active heterosexual Latter-day Saints generally believe in a highly loving and highly involved God, what Froese and Bader refer to as the “benevolent God.”[16] According to the survey data, LGBT Latter-day Saints do not consider God to be as loving as heterosexual Latter-day Saints do. This is not to say that LGBT Latter-day Saints believe in Froese and Bader’s “critical God,” who is described as being uninvolved and unloving.[17] They simply do not believe that God is as involved and loving as the heterosexual Latter-day Saints report.

For instance, when those who responded very well and somewhat well to the question “How well do you feel the word ‘loving’ describes God?” are totaled, 68 percent of LGBT Latter-day Saints report believing in a loving God. However, they are less enthusiastic about that belief than heterosexual Latter-day Saints, who responded very well to that same question at 86 percent and had no respondents report not at all. Additionally, LGBT Latter-day Saints have more diversity of opinion on the extent to which God is loving, with a combined 31 percent of participants responding undecided, not very well, or not at all to the question. This is compared to 7 percent of heterosexual Latter-day Saints who responded the same.

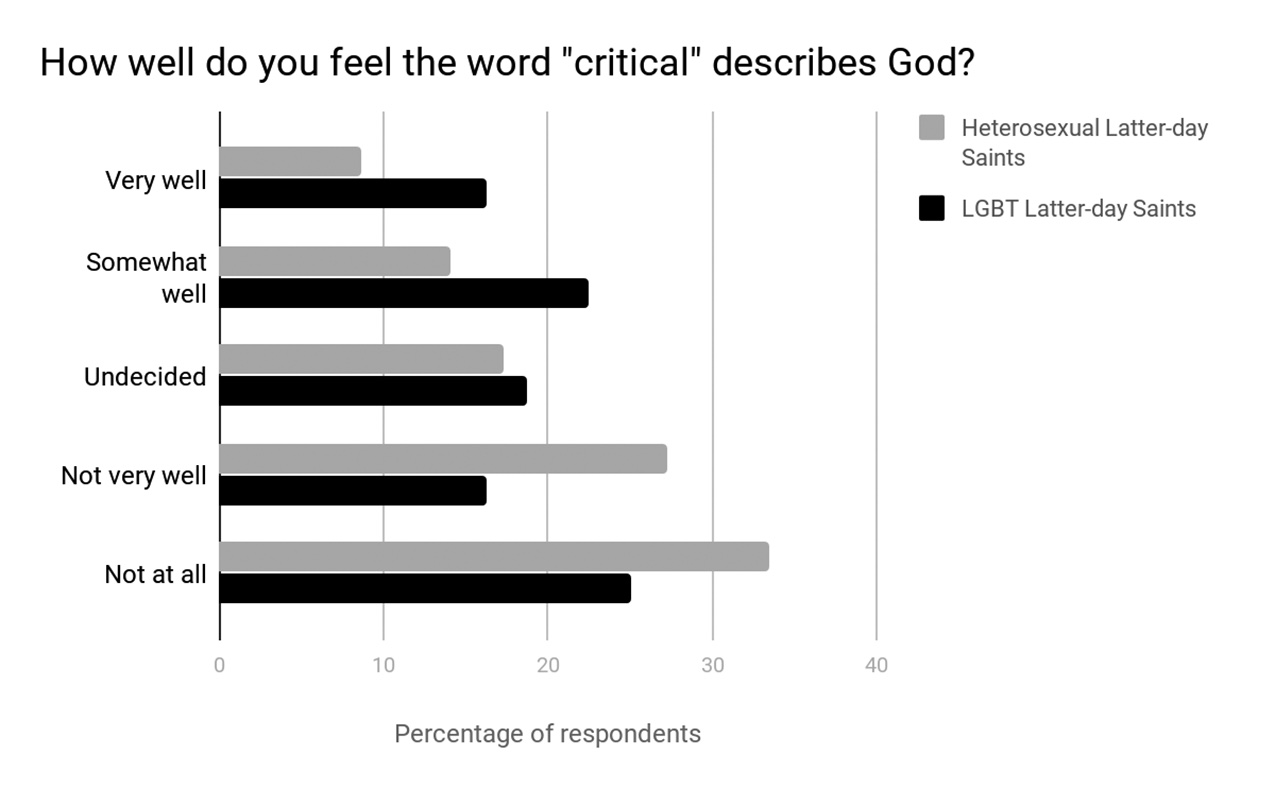

Additionally, while LGBT Latter-day Saints do not believe in the “critical God,” they are more likely to describe God as critical when compared to heterosexual Latter-day Saints.[18] LGBT Latter-day Saints generally are much more ambivalent about the question; just as many responded very well as did not very well when asked “How well do you feel the word ‘critical’ describes God?”

LGBT Latter-day Saints’ comparative ambivalence to the question of God’s love may be more a product of their mixed levels of church attendance than their sexuality. As the interview data will show, church-attending LGBT Latter-day Saints continue to believe that God is highly loving and not at all critical.

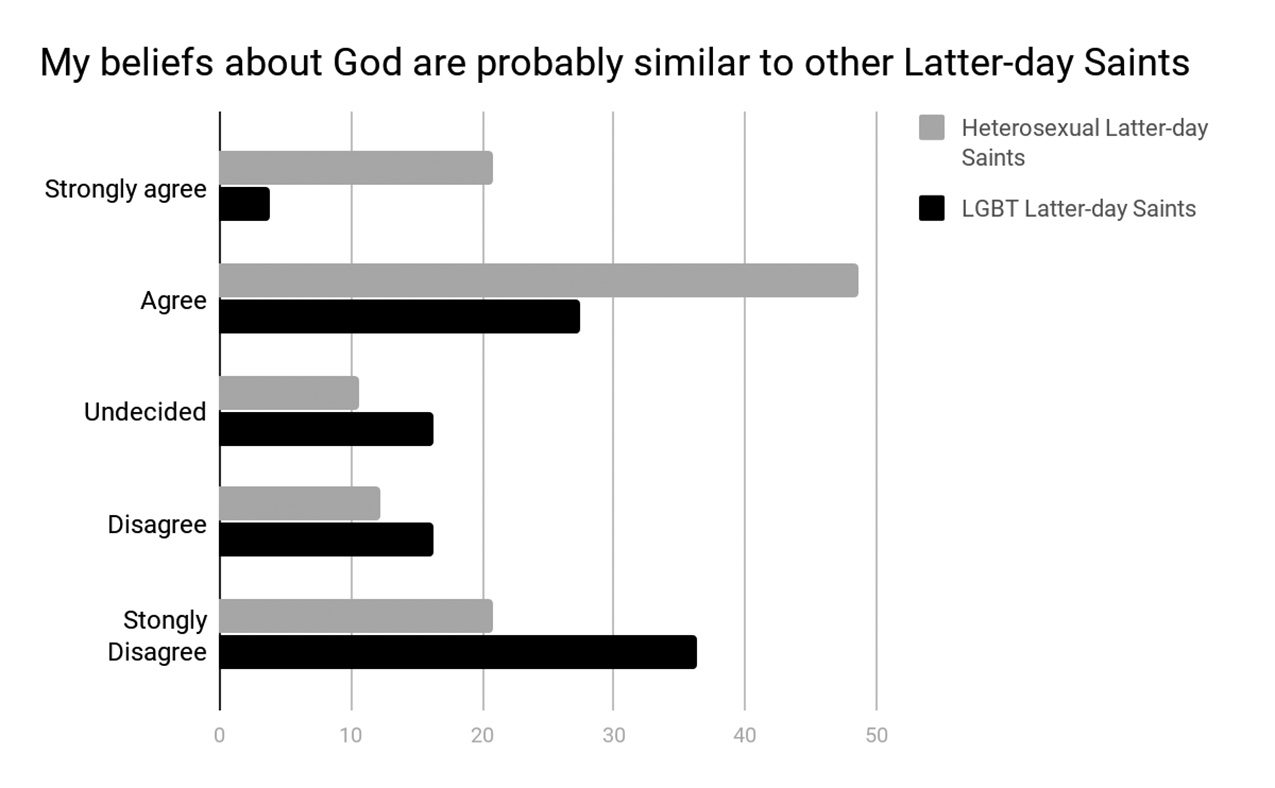

Lastly, LGBT Latter-day Saints are much less likely than heterosexual Latter-day Saints to believe that their beliefs about God are similar to other Latter-day Saints. The qualitative data will expand on this point and show that in order to continue to attend church, LGBT Latter-day Saints often have to rely on their own interpretation of Church teachings.

Interview Data

One question in this study was why LGBT Latter-day Saints would choose to remain active members of the religion and, in addition, how they find space for themselves within the community. In answering these questions, the LGBT Latter-day Saints interviewed gave replies that fell along several themes. Tony is a believing though now inactive (meaning no longer church-attending) gay Latter-day Saint living in a small studio apartment in the middle of LA. He was unassuming but excited to participate. His family, he told me, was originally from the Philippines and nearly all Latter-day Saints. He “discovered” his sexuality while still in his teens. He began to fall out of the Latter-day Saint lifestyle much to the chagrin and dismay of his very faithful family. The predictive course of this story is interrupted, however, by a spiritual encounter with God.

In something of a last-ditch effort to commune with the divine, Tony took Latter-day Saint truth claims to their source, God, for verification through prayer. Tony did not expound on exactly what he felt during his prayerful encounter with deity; however, whatever it was that Tony felt was sufficient to convince him that, in his words, “it’s all true.” This realization of truthfulness led Tony to serve a mission for the full two-year assignment. Upon returning home, Tony attended a singles ward, a congregation reserved for young single adult Latter-day Saints whose purpose is to provide opportunities for marriage among Latter-day Saints. For a few years, he had decided on a life of celibacy inside the faith. In time, however, the heavy burden of celibacy proved too much for Tony and, while he never stopped believing in the Church’s truth claims, he stopped attending, stopped seeking to live a life of celibacy, and began trying to find a man with whom to start a family.

I asked him explicitly, “Why not stop believing it?” Wouldn’t it be psychologically easier, I reasoned, to find a new system of belief that better fit the life he hoped to lead? He couldn’t, he told me. “It’s all true, the whole thing,” he said. “What will that mean for you in the afterlife?” I asked with curiosity. He had no idea. Whether he would be gay or straight in the life to come, he had no idea. It was here that I took a different turn in my questioning. “If Mormonism is true, why not attend Mormon meetings?” His answer: “It’s too hard.” He explained that when he attends church meetings, “Mormon Tony pops back up” and starts saying things like, “You should try to be celibate again.” In an effort to avoid “Mormon Tony,” it was just easier to not attend. In other words, Tony couldn’t deny his experience, but he could try to forget, and, for him, that has seemed to be the best option.

In the previous section, one participant was able to comfortably affirm God’s love and involvement. Tony, in contrast, believed in those attributes of God—after all, God was involved and concerned enough about Tony to personally tell him that Mormonism was true. But, in the end, the task of continuing to believe in and worship an involved and concerned god was too much for him emotionally.

In contrast, there were other LGBT Latter-day Saints who felt that their sexuality had actually brought them into greater intimacy with God. For example, Brandon, a young man in his late twenties made what was, in the moment, a surprising claim. I asked him to try and explain to me how his being gay may have impacted his understanding of God. Thinking for a moment and looking slightly upward, he suggested, as if realizing it for the first time, “I think my being gay brought me closer to God.” He had felt alienated by his church community, there was no way around that; however, he also felt that in his alienation he had found greater access to the divine.

This was not an unusual claim, and, in fact, it became common among interviewees (though, strangely, this conflicted with the polling data). When another interviewee, Jason, was asked this question, he responded near automatically, “Absolutely . . . for better and for worse.” On one hand, he explained that it “is frustrating that a heavenly parent, a Heavenly Father, would allow continuing things that are . . . incorrect,” meaning the continuation of, as he saw them, false statements regarding LGBT peoples from both lay members and leadership in the Church. Jason’s “frustration” was that God seemed to be working below the standards of benevolence and involvement Jason had come to expect. He could not understand how a loving God could allow the leaders of the Church, with whom God is able to communicate directly, to continue to preach false ideas (as he saw them) regarding homosexuality. Jason’s discomfort and confusion about the Church is therefore rooted in his belief in a “benevolent God.”[19]

Jason continued, however, by saying, “On the good side, you are forced to engage with God on a drastically more personal level.” The God he discovered through this forced engagement is, in his view, very different from the more judgmental God he found from “General Authorities and prophets.” The God Jason found from this engagement was, in his view, more loving and accepting than how he believed Mormons generally imagined God. This claim is also seen in the quantitative data, where LGBT Latter-day Saints showed they are far more likely to say they do not believe like other Latter-day Saints.

Many of the LGBT Latter-day Saints interviewed in the present study took care to distinguish between the Church and God. In an effort to make church more comfortable and edifying, many interviewed would fall back on their personal conviction of God’s benevolent nature over any judgement (perceived or otherwise) from members in their congregation. Ian was a fine example of this. I met him in a small coffee shop, an ironic location given the Latter-day Saint prohibition against coffee. He entered excitedly, ready to share his story. Ian was a gay man and a believing Latter-day Saint, still very active in his congregation. I asked him if he was out to his congregation, “I’m sure they suspect,” he said, “but I haven’t come out to anyone.” We then discussed the discomfort he feels on the typical Sunday. While he has found not coming out to his fellow churchgoers a more manageable scenario attending his Latter-day Saint congregation, church attendance was nevertheless sometimes rather stressful. I asked him, “So, going to church is hard, but it’s still important to you. How do you get through church?” He paused, and after taking only a moment replied, “Well, I go for me.”

Responses like this were given frequently as I discussed this question with active and believing LGBT Latter-day Saints. For those who were able to make space for themselves within Latter-day Saint worship, it was imperative that they make the communal experience into an individualized one. By this I mean: for this group who was able to find a balance between being queer and being active Latter-day Saints, they needed to find a way to be selective in what in the faith was of value and what was not. Put into words more in tune with their own description, it became necessary to differentiate between what was real and what was simply other Latter-day Saints’ opinions. In this vein, Ian continued, “Every now and again I sit in Sunday School and I tell myself, that’s just what she thinks.” God’s accepting benevolence outranked any side comments from fellow members of the Church.

In conclusion, for these LGBT Latter-day Saints, there is a separation between church and God. Where the Church is faulty, God is perfect. Where the Church doesn’t understand, God has compassion. It must be noted, however, that, in their view, this does not delegitimize the Church. Rather, God becomes the standard that the Church simply hasn’t yet met but might shortly. God’s seeming unwillingness to debunk prohibitions about homosexuality remain confusing (especially given their perception of God’s direct involvement in the Church), however, God remains benevolent, even when his Church falls below that standard.

Post–Latter-day Saints

For post–Latter-day Saints, the data suggests a God who couldn’t be more different from Froese and Bader’s “benevolent God.”[20] Post–Latter-day Saints report belief in a God who is, when compared to the believing Latter-day Saint, far more distant and critical and less loving. Occasionally, post–Latter-day Saints, due to a difficulty of reconciling the Church’s faults with an involved and loving God, abandoned the idea of God altogether. Furthermore, others saw the God displayed in Latter-day Saint scripture or worshiped in Latter-day Saint meetings as far more oppressive than benevolent.

The data, therefore, might be interpreted both in terms of post–Latter-day Saints’ actual belief as well as their disappointment with the God they encountered in Latter-day Saint worship. Furthermore, as has been seen previously, the Latter-day Saints’ image of God is often sculpted by their experience at church.

Survey Data

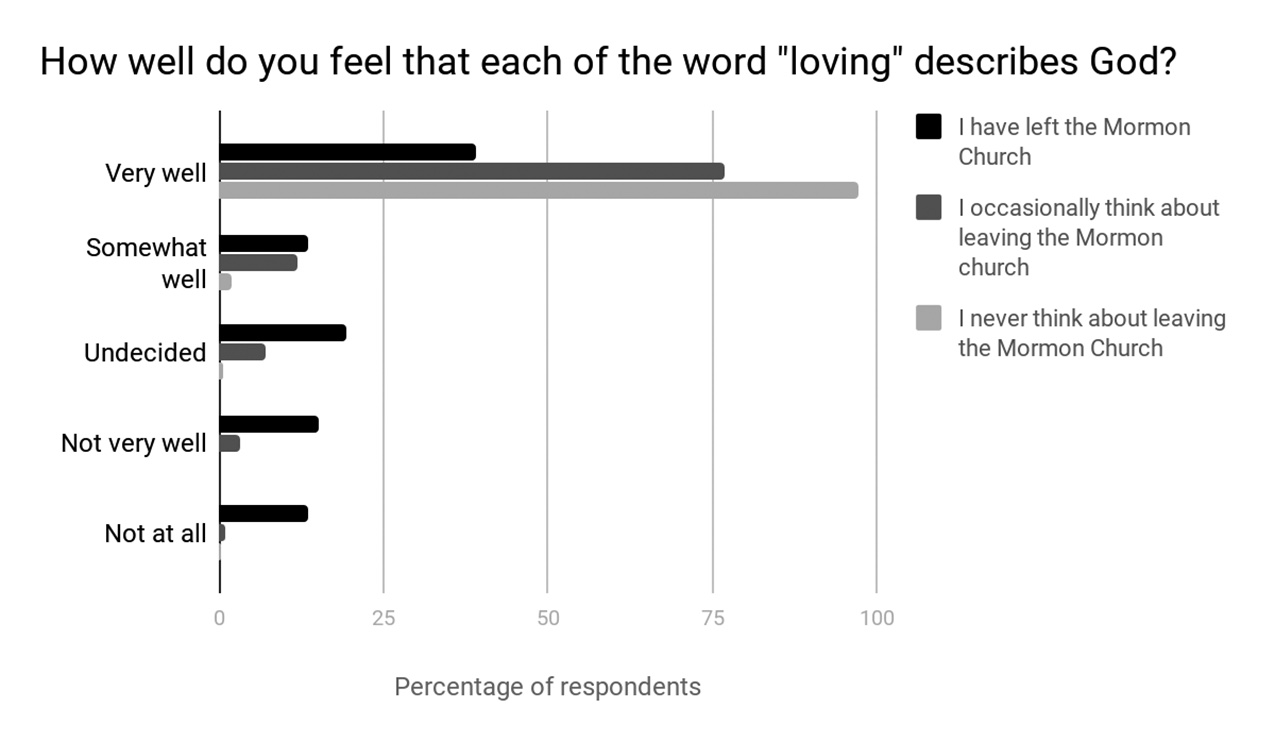

This section compares the survey data from those who report having left the LDS church with two other groups: those who report never thinking about leaving and those who report occasionally thinking about leaving. The intention is to showcase trends across a spectrum of satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with the LDS Church.

Thirty-nine percent of those who report having left the LDS Church agree that loving describes God well. In contrast, that number increases to 77 percent for those who occasionally think about leaving the Church and 97 percent for those who never think about leaving the LDS Church. Froese and Bader argue that most everyone who believes in God believes God to be loving.[21] Therefore, it is possible that this low number represents the God post–Latter-day Saints found unsatisfactory within the LDS Church rather than a god they continue to believe in. The same explanation might be applied to those who occasionally think about leaving the Church. Whatever the explanation, post–Latter-day Saints did not experience a loving God within the walls of LDS Churches.

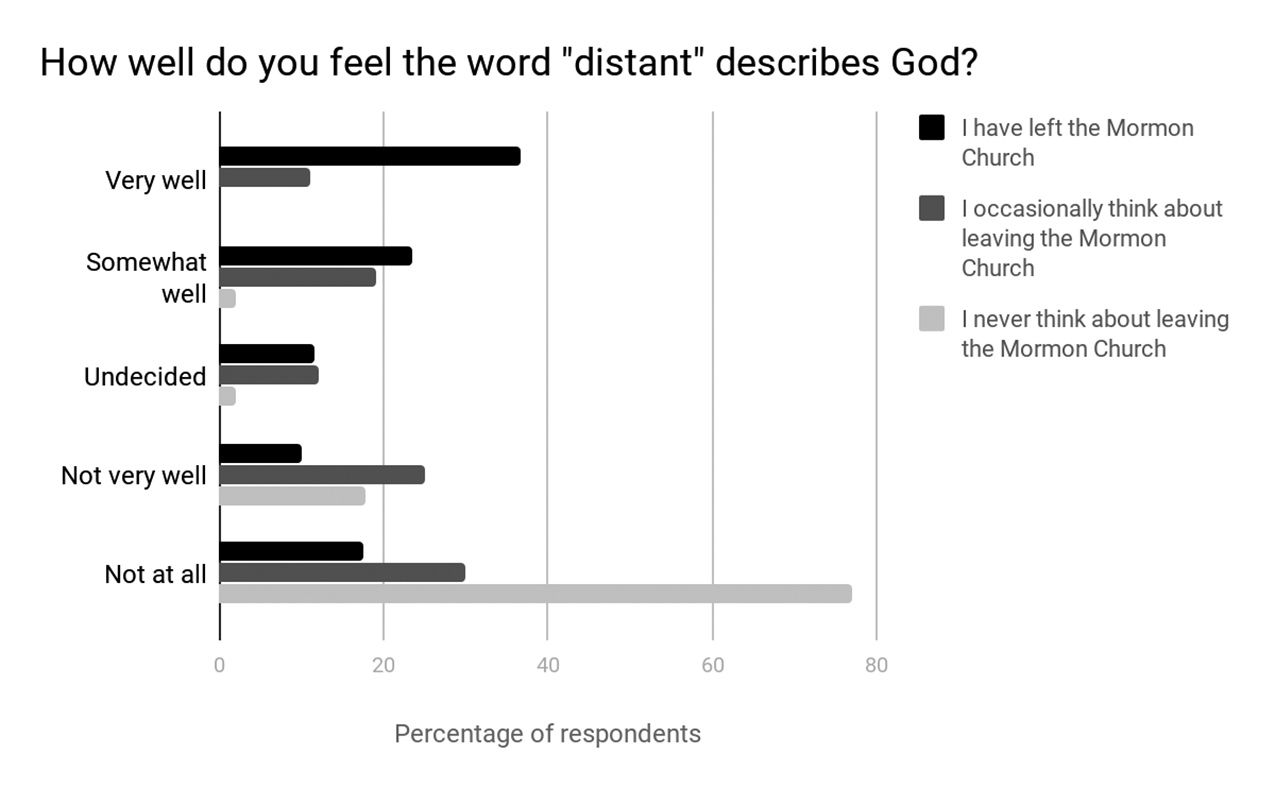

The opposite trend occurs as participants engage with the extent to which God is distant and critical, as we see in figure 8. A combined 60 percent of post–Latter-day Saints report that distant describes God either very well or somewhat well. This is in sharp contrast with those who never think about leaving the LDS Church, none of whom felt it described God very well and 76 percent of whom felt the term did not describe God at all. Those who occasionally think about leaving fell between the two.

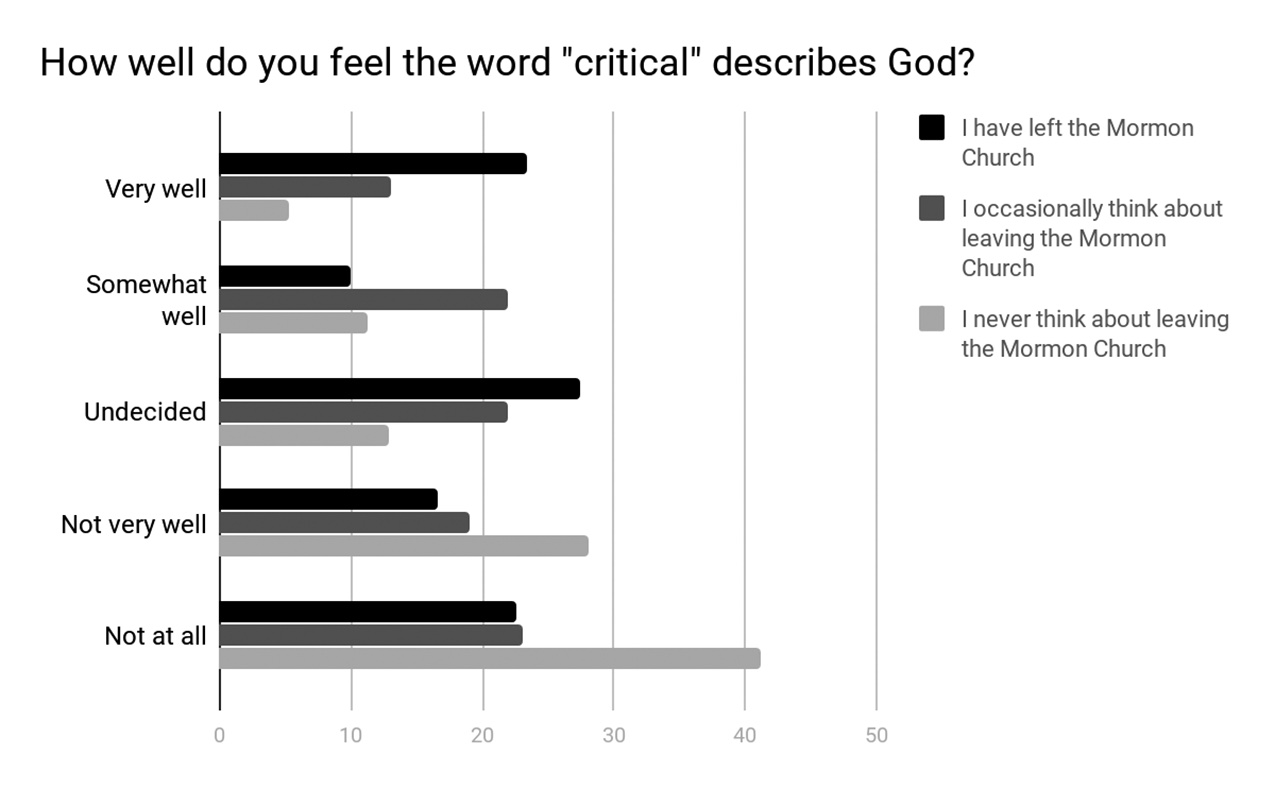

In contrast, the extent to which God is critical drew more ambivalent results from post–Latter-day Saints; 23 percent report that it describes God very well, 22 percent say not at all, and 27 percent are undecided. Their ambivalence is matched by only a little more certainty among those who never think about leaving and those who occasionally do. It seems that while Latter-day Saints generally believe in a highly loving and highly involved God, there are many who harbor the possibility of God also being critical.

Interview Data

For many post–Latter-day Saints, their experience as a member of the LDS Church was self-reported as being dysfunctional, oppressive, or domineering.

For Anne, a respondent typical of others, her de-conversion began when the Church stopped working for her.

I felt like a lot of what was being taught in church was actually quite counterproductive. . . . There’s a lot of teachings that lead you to think, “Well if you’re sad you must be sinning,” you know, “if you’re having a hard time you must be doing something wrong,” and then there’s so much expectation with church involvement that I think that can make people a little more anxious or perfectionistic. So, this kind of stuff. . . . I saw a lot of damage to women from the Church or what I perceive as detrimental stuff for women. And then the stuff with homosexuality and the Church’s involvement in that. All that kind of built up to me seeing a lot of things where I felt like the Church was doing a lot of harm.

Note here the conflict between Anne’s lived Latter-day Saint experience and what one should expect from the “benevolent God.”[22] A highly loving deity, Anne believed, would not head a system that detrimentally affected her mental health. She continued:

I kind of started to feel like there wasn’t a lot of solid ground for some of the Church’s truth claims. And it kind of came down to, like, I felt like if the Church had really solid truth claims [and] then there was some kind of negative collateral damage happening, like I could maybe stick with it. Like the true points were kind of tricky but like if everything the Church did turned out great, that would probably be okay too. [But] then also I felt like, you know, the crux of the Church’s truth points kind of comes down to . . . you pray about it, you feel that it’s true and . . . it comes out a lot to what I perceive as [an] emotional response. And I didn’t feel like that was enough . . . to justify the harm I saw being done.

Anne’s expectation of a more forceful response from God rather than just an “emotional one” makes sense given Latter-day Saints’ assertion that God is involved enough to answer prayers with clarity. And her dissatisfaction with the lived reality of the Latter-day Saint experience is made worse by her prior conviction that God is both benevolent and involved enough to make the Church better than what it is.

As seen in the data, typified by Anne’s narrative, the challenges of faith experienced by post–Latter-day Saints are rooted not only in their experience in the Church or with its history but also in the perceived contradiction between all those things and the Latter-day Saint understanding of God as involved and loving. That is the cost, it seems, of a highly involved and loving deity.

Spencer, another respondent, was asked what the most influential factor was in his leaving the LDS Church. He replied, “I would say it came down to . . . Joseph Smith’s character and the things that he did and said that I find very immoral and very questionable. I guess the plausibility theories that the Church offers versus the theories that historians offer up in naturalistic explanations were just much less convincing. This man is not who I thought he was.” George has a similar experience. He grew up in a devout Mormon family in Utah. Once he was a young adult, George realized he was starting to have questions related to the Church’s history and policies. Eventually, he began to investigate other internet sources including an ex-Mormon subreddit, despite a warning from a friend. Once on the subreddit, he discovered racist quotes from former Church leaders and became increasingly interested in the Church’s former policy of not allowing men of African descent to hold the priesthood. He asked rhetorically, “God is totally cool with leaders being super racist? It’s just all really [weird].”

To understand the concerns of these post–Latter-day Saints, it is imperative to remember that their quandaries were not simply with Church history or policy but also in the difficulty of reconciling the “benevolent God” with their respective concerns.[23] In Anne’s case, if she had not expected such a forceful and clear witness from deity, her cognitive dissonance when met with feelings would have been less so. For Spencer, it was not simply an issue of Joseph Smith lacking in character, it was also the question of how an involved and loving God would allow an immoral man to be his mouthpiece. For George, while his faith crisis had its origin in issues of Church history and policy, it became a concern about the nature of God. How could a God who is involved and loving allow the leaders of his Church to be overtly racist? That question, left unanswered for George, became a catalyst that ultimately motivated his departure from the LDS Church.

In Summary

In each section, I have argued that the experiences and identity of each Latter-day Saint has impacted their conceptualization of God. Among the post–Latter-day Saints, we see those who could not bear the cost of believing in a “benevolent God.”[24] Reconciling this God with the lived realities of Latter-day Saint worship, the darker shades of Latter-day Saint history, or their own feeling of distance from deity proved to be a task far too complex to undertake. The cost required to make this reconciliation led them away from church and, in many cases, from the idea of God altogether.

For others, God could still be found outside of the LDS Church. They perceive God as more distant and uninvolved, far from the loving Heavenly Father described in the contemporary LDS understanding of Joseph Smith’s experience. What seems very clear in the reflection of this data is the reality that, for Latter-day Saints, the image of God is sculpted and molded in the shadow of their church experience.

This project found that active Latter-day Saints believe in a highly involved and loving God. They were freer than other LDS groups to believe in such a God, as there was no cognitive dissonance to satisfy, in contrast to the LGBT and post–Latter-day Saints. Additionally, it was found that the more engaged a person was in the LDS community, the more they believed God to be involved and loving. In contrast, post–Latter-day Saints tended to believe in a God who was not only less involved but less loving as well.

Active LGBT Latter-day Saints faced daunting questions regarding cost and reward and had to reframe their understanding of God in order to ensure that their cost did not outweigh their reward. Many did this by creating a God who was highly loving but less involved to explain why Church leaders could be “wrong” about homosexuality. Others nuanced the idea of God’s level of involvement by supposing that the degrees of involvement could vary from person to person. The strength of their personal connection to deity gave them the self-assurance to disregard what other Latter-day Saints said about issues of gender and sexuality. Interestingly, while post–Latter-day Saints view God either as the source of their oppression or the apathetic bystander to an irrevocably faulted church system, LGBT Latter-day Saints (at least the active and believing LGBT Latter-day Saints interviewed) view God as their ally. While both have significant struggles with the Church—whether in terms of history, policy, culture, or all the above—for one group God was their tether to faith while for the other he was the final straw.

The present study has expanded on Froese and Bader’s work by including the Latter-day Saint community, a denomination ignored in their initial study. Additionally, with its inclusion of LGBT and post–Latter-day Saints, it incorporated an additional group Froese and Bader ignored: the marginalized and the unbelieving. It reveals that their framework is effective not just for those sitting in the center of the pews but also those standing at the margins.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Paul Froese and Christopher Bader, America’s Four Gods: What We Say about God—And What That Says about Us (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 27–31.

[2] Froese and Bader, 35

[3] Froese and Bader, 52.

[4] Froese and Bader, 41.

[5] Jan Shipps, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 21.

[6] For instance, see Gary E. Stevenson, “How Does the Holy Ghost Help You?,” Apr. 2017; Henry B. Eyring, “The Holy Ghost as Your Companion,” Oct. 2015.

[7] Michael Hicks, Mormonism and Music: A History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 102.

[8] Terryl Givens and Fiona Givens, The God Who Weeps: How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life (Salt Lake City: Ensign Peak, 2012), 21.

[9] Froese and Bader, America’s Four Gods, 27–31.

[10] Froese and Bader, 27–31.

[11] Froese and Bader, 27–31.

[12] Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism, vol. 3 (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 13–14.

[13] Froese and Bader, America’s Four Gods, 28.

[14] Froese and Bader, 28.

[15] Note that this is a merged total of respondents who agreed and strongly agreed with the statement regarding Joseph Smith.

[16] Froese and Bader, America’s Four Gods, 28

[17] Froese and Bader, 31–32.

[18] Froese and Bader, 31–32.

[19] Froese and Bader, 28.

[20] Froese and Bader, 28.

[21] Froese and Bader, 80.

[22] Froese and Bader, 28.

[23] Froese and Bader, 28.

[24] Froese and Bader, 27–31.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue