Articles/Essays – Volume 43, No. 4

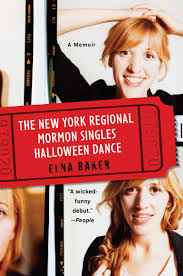

The Plan of Stagnation | Elna Baker, The New York Regional Mormon Singles Halloween Dance: A Memoir

The New York Regional Mormon Singles Halloween Dance: A Memoir by Elna Baker is a book about Mormons for an audience of non-Mormons; for that, everyone who works in the field of Mormon literature should be grateful. It attempts—and more importantly succeeds in—making Mormons human and complex to outsiders; it even makes us somewhat intelligible. Baker addresses the impact of “preconceived notions” about Mormons on her relationships: As soon as she acknowledges her religion, she goes “from being anything they can imagine to being defined. Immediately we stop talking about books or films. Instead, every question is about whether I’m a polygamist, whether I’ve had sex, whether I wear magic underwear, and whether I believe in dinosaurs” (18). As fascinating as those questions might be to non-Mormons, the book’s primary value may nonetheless be in what it reveals to Mormons, about ourselves—or more specifically, what it reveals about “our bodies, ourselves” (though admittedly not in quite the same way as the book by that title published by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective), as well as our reluctance to ex amine some of the implications of embodiment, not merely with a speculum, but even in a full-length mirror.

Baker, a twenty-something stand-up comedienne with a degree in drama from New York University, has written what many people consider a very funny book. A triumphantly hilarious moment involves Baker impulsively lobbing a tangerine at a particularly snide, mean-spirited family home evening group leader, hitting the evil woman so firmly between the eyes that her chair tips over backwards.

Throughout the book there’s situational humor; there’s good comedic timing; there’s wit. A striking example of all three in volves Baker’s “brilliant” plan to attend the titular Halloween dance dressed as a fortune cookie. Unfortunately, after a long subway ride, she realizes to her utter horror and shame that her costume actually looks like a giant vulva. She then does what she must: “I took my vagina off and hid it in the broom closet (which I guess is what is what you do every time you go to church)” (182–83). She asks someone to find her sister, who is also at the dance; her sister “emerged dressed as a black cat. While we hadn’t planned it, we’d both chosen to go as pussy” (183).

Not all the humor is quite so risqué, but a good deal of it is. The book is primarily about sex, and the ambivalence it arouses in people who desire it but adhere to inviolable rules about who can have it, whom they can have it with, and under what circumstances. As a result, the book is also about bodies, those transformative objects that the plan of salvation tells us we come to earth to obtain.

The female body is central not only to Baker’s book, but to the story of the Fall, one of the primary scriptural texts Mormons rely on for their understanding of the plan of salvation. Therefore it’s worth deviating momentarily from Baker’s memoir in order to underscore certain aspects of female embodiment as set forth in the story of the Garden of Eden—specifically, that Eve’s punishment for her transgression is focused on and through her body. In Genesis 3:16 God tells Eve, “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.” The translation offered in the New Oxford Edition is more to the point: God says, “I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children; yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.”

Thus, according to Genesis, women live with a bodily conflict: they desire their husbands, and this desire exists because without it women would not risk the divinely decreed pain and suffering involved in childbirth. In other words, the punishment is not merely the pain and suffering of childbirth, but the conflict of de sire and pain felt in and by a single body, a conflict that is both theologically mandated and capable of causing a profound alienation from the source and site of the conflict: one’s body. No doubt this conflict affects individual women differently, depending in part on the extent to which they internalize the story of Eve; and no doubt some women manage, either by sheer luck or persistent hard work, to inhabit their bodies as comfortably as any woman can in a culture obsessed with physical beauty and perfection. Regardless of whether Baker would accept my assessment of the theological issues underpinning some of the anxiety and distress women in our society can feel about their bodies, she nevertheless presents one of the more dramatic stories of alienation from one’s body—and the damage that such alienation does to both body and soul.

Early on, Baker explains the plan of salvation to her readers and offers her reaction to it: “The primary purpose of life on earth was for me to get a body, any body; to appreciate it, make choices with it, ‘to shuffle off this mortal coil’ and return to God. By the age of five I had learned the meaning of life. There was only one problem: I got the wrong body—and I’d been hating it ever since” (51).

Baker’s body, you see, was fat. At one point, she weighed 260 pounds. In an orientation session for a rigorous, doctor-supervised, weight-loss program, Baker looks down at her body and realizes that she hides behind her clothing. She then asks herself, “But what do I look like naked? I searched my brain for an image of my body—not the one I saw in pictures, my real body. Nothing. My mind was blank” (83; emphasis hers). Only after carefully probing her memory is she able to recall a bath during which she had been unable to submerge all of herself; no matter how deep she sank into the tub, part of her stomach “floated above the water like a soft white hill. I looked at it and decided it was not part of me” (84).

Baker’s weight eventually drops to 145 pounds; she is not just thin, she is beautiful. This success, however, does not result in her being at home in her body. On a date with a man she has pursued aggressively, Baker excuses herself to use the ladies’ room, only to encounter a thin blond woman approaching her in a dim corridor. Not until she has traversed the length of the corridor does she “realize I was ten inches away from smacking into a full-length mirror” (140). She doesn’t recognize that this thin blond woman is in fact herself. What she does recognize about the woman is that “She’s kind of a bitch” (140; emphasis hers), knowledge so unassimilable that she does “the only thing I could: I put this information in a locked vault in my brain, and decided to forget it” (141).

The diet that let her achieve such dramatic weight loss is difficult to maintain; eventually, Baker regains some of the weight. Anxious to lose it without returning to the clinic that managed her diet in the first place, she finds a website that sells phentermine, the medication prescribed by her doctor to control her ap petite; she can purchase it provided she lies about her weight, so she states that she weighs 250 pounds and orders two bottles. About a week later, she ends up in the hospital with dangerously low blood pressure and a bruise on her head from passing out, the result of abusing amphetamines. Initially Baker tries to tell a friend that she is “not the kind of girl who diets her way into the hospital” (204), but the statement is self-evidently false. Further more, Baker realizes that the miracle of grace, the divine strength she discovered when she began her diet in earnest, the “BIG miracle” that had been “the closest thing I had to evidence of God’s existence, was actually just me—ON SPEED!” (204; emphasis hers).

Eventually Baker undergoes plastic surgery to take care of the excess skin left on her torso after her weight loss. In a consultation, the surgeon warns that “one of the side effects of getting breast implants is that you may lose your nipple sensation.” Baker’s shocked response: “Your nipples have sensation?” (231) The line is played for laughs, but the fact that she chooses to risk losing sensation in her nipples before she even discovers how pleasurable and illuminating that sensation can be is, I must point out, really quite sad.

It is not only Baker’s body but at times her psyche that seems foreign to her. She acknowledges several times that she lies “consistently” (136) for reasons that elude her. For instance, she impulsively tells a boy she has a high school crush on that she has never seen snow, even though she has been skiing in the Alps (41). Like most people, she occasionally engages in behavior that she realizes is ridiculous and unappealing, but she certainly depicts her bouts of this affliction as fairly severe and long-lasting—and not especially amusing. When that cute boy from high school offers, a few years later, to be her boyfriend, she is “transformed . . . from an intelligent articulate person into a semiretarded schoolgirl” who repeats everything the boy says and blows bubbles in her milk glass, until he breaks up with her after only a few hours (47). As an adult, when asked if she believes in evolution or creation ism, she answers, “I don’t know.” Pressed for an answer, she can only state, weakly and ineffectually, “I guess it’s one of those things I try not to think about” (158).

Not surprisingly, confusion about what she really wants or believes is most severe in matters of love and sex, matters that involve the body she has ignored for so long. In the midst of trying to seduce Matt, her atheist boyfriend, and lose her virginity, she finds herself derailing the enterprise by telling him, “You need to pray and find out if God exists” (172). And when she finally ac quires the Mormon boyfriend she has longed for all her life, she realizes he’s not what she wants after all. She prepares to break up with him, only to hear herself say instead, “I love you” (228), a statement that the text does not explain or comment on in any way. Baker doesn’t tell us if the statement was sincere, or how she reacts to hearing those shocking words come out of her mouth. She merely states that she says the words, closes the chapter, and moves on to another chapter about plastic surgery.

I realize I’m presenting a skewed version of the book here—one that ignores many of its wise and charming aspects—and that I’m using Baker to make a larger point about self-knowledge, embodiment, and faith. But the point is worth making, and worth understanding, so I’ll persist.

Baker does her best to explain, sincerely and responsibly, her sense of her spiritual life. Of her decision to be baptized at age eight, Baker writes, “I prayed about it. After my prayer, I tried to be as still as possible so that I could hear my heart. I listened, my heart felt warm, and I felt good inside” (10). Certainly this adheres to the Mormon formula for recognizing “truth.” But this truth is recognized through Baker’s body: It is her visceral, embodied response to a mental question she has posed. And as she herself states repeatedly, both her body and her mind confound and con fuse her; they do not provide her with reliable information, and she often refuses to assimilate the information they do provide.

Consider, for instance, Baker’s reliance on the Mormon truth recognizing formula in the matter of marriage. When her Mormon boyfriend proposes, she fasts for two days, then goes to the temple and offers the following prayer: “God, I’ve decided to marry Hayes. Is this the right thing to do?” Soon, she gets a response: “Yes, Yes, Yes, all through me, YES, do, do, do” (241; emphasis hers). Which seems pretty conclusive, except for two things: (1) the boyfriend decides soon thereafter not to propose; and (2) Baker realizes she doesn’t really want to marry him after all (244). Eventually, she even acknowledges that he never made her happy (246). I must ask: How unaware of your own mind and motivation must you be to need an answer from something outside you to tell you whether to marry a person who has never made you happy?

But despite the fact that Baker’s unreliable body and unreliable mind conspire to offer unreliable spiritual advice, the book discusses spiritual experiences—which, I must repeat, are mediated through our bodies—as if they are ultimately and conclusively intelligible, infallible, and immutable. They are not merely testimony of what matters to us at a particular time, of our investment in our own lives, and of our need to seek self-knowledge; they are an absolutely reliable basis for embracing and affirming not just one decision at one moment in time, but an entire belief system—forever.

After a painful breakup with Matt, the atheist boyfriend she’d fallen in love with, Baker begs God for “a spiritual experience that will anchor me. Give me something that for the rest of my life I can look back on and say, ‘When I was twenty-three I had a moment—and I’ve never looked back since.’ I will walk in any direction you tell me, but please God I need a direction” (210; emphasis hers). In response, she notices “a warm feeling in the center of my chest” and hears a series of questions, the final one of which is, “Is everything you want in life available to you within this church?” (211)

“Yes,” Baker answers, knowing it’s true as soon as she says it. But there are questions neither she nor the voice asks, including, “Are you going to want the same things all your life? Are there things you haven’t allowed yourself to want, desires you haven’t allowed yourself to acknowledge, needs you claim aren’t part of you, just as you didn’t allow yourself to see your own body?”

Baker concludes the book by recounting a visit to Zambia to visit Matt. Once again she attempts to seduce him, a plan that goes awry when he asks her if what they’re doing is okay and she admits that she has no idea what she’s doing. Analyzing the situation later, she writes:

It wasn’t Matt’s fault that things didn’t work out. He didn’t hate me or think I was repulsive. He simply asked me if I had made up my mind. Which I hadn’t. So we were back at square one. And the thing is, I think I’m courageous for staying true to myself but really I’m deathly afraid of making the wrong choice. For good reason. Either way I choose, my life will become so much smaller. If I stop being Mormon, I won’t be allowed to attend my brother’s and sisters’ wed dings in any Mormon temple. I’ll break my mother’s heart and I won’t be with my family for eternity. But if I stay in the church, I can’t wear the sleeveless dress I wore last night, I’ll have to say fetch instead of fuck, and I won’t get to live the rest of my life with any of the men I love most. (272)

I must point out the differences in the equations Baker sets up: Stop being Mormon = excluded from family weddings, break mother’s heart, and separated from family of origin for all eternity, while stay in the Church = no sleeveless dresses, less profanity, and disappointment in love. But it’s not as if disappointment in love can’t happen anywhere, to anyone, no matter what their relationship to religion; it’s not as if leaving the Church guarantees that a person will fall in love with a fabulous atheist who will love her back. And the larger point is that, while Baker has a clear sense of the negative consequences of leaving the Church, she has little sense of positive consequences, aside from how they affect her wardrobe and, possibly, her love life. The truth is, there’s an entire world of questioning and discovery and connection and depth and grace (a term that Baker has no real sense of when she first encounters it in Ether 12:27, since it is historically under-emphasized in Mormonism) that becomes available when you finally choose the world—or, more accurately, acknowledge what you’ve chosen.

Grace, after all, is the unmerited love of God, freely given; knowing that we are accepted by divinity no matter what our faults and flaws, we supposedly find it easier to accept ourselves. Nonetheless we all question our choices from time to time; we all second-guess ourselves. But if Baker had made the right choice by staying in the Church, the need to remake that choice would not be so frequent, so fraught, and so painful. It’s so easy to see that Baker has made what is the right choice for her—the choice to leave—but she can’t follow through, so she lives as if she’s made the opposite choice. Her plea for a spiritual experience from God that will eradicate any need to regret or seriously revisit her refusal to leave follows weeks and weeks of Sunday meetings during which Baker sits in church and thinks, “I gave up an incredible per son for stale bread and an uncomfortable pew” (208; emphasis hers). It’s hard not to respond, “Yes, Sister Baker, that’s exactly what you did, and the world is a poorer place because of it.”

I do not mean to imply that leaving the Church is the only way anyone can experience grace. I don’t think that’s true, though I do think it’s clear that Baker finds little sense of grace in Mor monism and should be free to search for it elsewhere. I therefore also think that it’s important to reject the false dichotomies Baker establishes: body versus soul, Mormon versus non-Mormon, and the easy corollaries she attaches to them: body = pain; soul = happiness; Mormon = everything you really want in life; non-Mormon = great sex and fun in this life, but loneliness and grief in the next. The world is more complex than that, even for Mormons, and we need literature that acknowledges that fact.

What Baker ultimately ends up describing is a plan not of salvation but of stagnation. It’s designed, as she acknowledges, to provide anchors, to ensure that we never revise youthful decisions or outgrow our earliest ideologies. These theological implications are probably not what the non-Mormons for whom the book is in tended will focus on, but they are hard to miss for someone who has actually made the choice Baker dilly-dallies over.

A pivotal moment in the memoir involves Baker seeing herself in an amusement park mirror—and not just any mirror, but a mirror that makes her skinny, a mirror that offers her a clear vision of a better version of herself. It is this vision that gives her the resolve to pursue her diet. Both before and after the diet, Baker has great talent and enormous appeal, just as she has talent and appeal whether she writes from the point of view of an active or an inactive Mormon. I will certainly read her next book. I can’t help hoping, however, that it will introduce us to the person Baker can be once she makes a choice she can live with. In the meantime, The New York Regional Mormon Singles Halloween Dance offers Mormons a glimpse into a mirror with a different perspective, one that helps us see some of what we do not recognize about ourselves until we attempt to explain ourselves to others.

Elna Baker. The New York Regional Mormon Singles Halloween Dance: A Memoir. New York: Dutton, 2009. 276 pp. Cloth: $25.95. ISBN 978–0–525–95135–3

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue