Articles/Essays – Volume 42, No. 3

The Long-Distance Mormon | R. A. Christmas, The Kingdom of God or Nothing!

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

With his poem, “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Mormon,” R. A. (Robert Allen) Christmas, among the most flickeringly idiosyncratic lights in the Mormon literary cosmos, may have (purposely or unconsciously) described himself as a living exemplar of the poem’s evocative title. The poem’s protagonist, however, is a high priests’ quorum instructor named Melvin, who was married for fifty years to a Mormon woman before he joined the Church and took his wife to the temple—but only after realizing he was too old to continue playing tennis on Sunday.

Christmas, converted to Mormonism in 1957 by his high school sweetheart, has since set his work apart as an exotic growth—less lush than pointed and prickly, less lyrical than pro saic. In such anthologies as Greening Wheat, Harvest, and Tending the Garden, he distinguishes himself as a tough, resilient vine that wraps its tendrils around our shared cultural eccentricities and won’t let go. In contrast to the more aesthetically pleasing, but sometimes less adventurous growths in the garden, Christmas’s poems insinuate themselves with frankness and a satiric, serpentine humor.

In “Loneliness of the Long-Distance Mormon,” Melvin’s priesthood lesson on eternal marriage provokes meditation by a thrice-temple-married quorum member who “can’t imagine his wives / (past or present) expressing / a Melvin-like satisfaction / with him—or he with them/ so he says nothing (as usual)/ during the discussion. / It bears scant resemblance to the life he’s led. / Tennis on Sunday mornings. / Doubles say, with some friends. From where he sits (left, rear) / it doesn’t sound half bad” (32)

The Kingdom of God or Nothing! reveals the poet’s fascination with (even pride in) the peculiarities of a peculiar people. He identifies with the naivete of a long-time temple goer in “Temple Film Ruminations,” who “thought he was hip, but it was / years before he realized all those/ shoulder-high hedges and holding/ of lambs and flowers against / chests were meant to indicate / that Adam and Eve were naked” (14).

Someone unfamiliar with Mormon culture might find this scene amusing (if not totally comprehensible), while other references might provoke, puzzle, or absorb the outsider, including such titles as “Savior on Mt. Disneyland,” “The Matriarchal Grip,” and “Beard Card.” Thematically, Christmas is nothing if not eclectic, writing breezily yet probingly about polygamy, polyandry, high school football, strategies for staying in the LDS Church, and the tendency of Latter-day Saints to claim a patent on the family.

Capable of an innocent yet brazen wit, Christmas can catch you off guard. Consider the delicious metaphor of “Soft Taco.” The poem’s first stanza reads:

It’s a lousy Latinate euphemism

that sounds like something wrong with

a snake—or like a defect in a kid’s

construction set. Erectile—you gotta be

kidding!—is politically comic—but

not when it’s your serpent, or your

tower that’s always collapsing. (34)

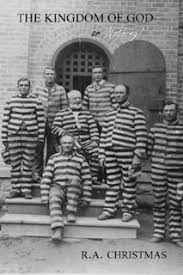

The cover of The Kingdom of God or Nothing! is a photograph from the 1880s of Mormon polygamists, including Apostle George Q. Cannon, wearing the traditional striped garb of prisoners while incarcerated at the Utah Territorial Penitentiary, then located in Salt Lake City’s Sugarhouse neighborhood. The phrase itself, of course, comes from Church President John Taylor’s self-proclaimed motto.

A curious aspect of the book is that Christmas devotes more than 5,000 words of the slim volume’s sixty pages to prose—a faux history of LDS polygamy, attributed to a fictional Associated Press reporter named Scott Holiday. The story reports the U.S. government’s return in 2025 of the Salt Lake Temple (plus temples in Logan, Manti, and St. George) to the LDS Church after 125 years in federal control. Christmas wants us to meditate on how the Mormon story might have taken an entirely different twist had the federal government decided to pursue violations of the Edmunds-Tucker Act (1887) when it discovered that polygamous temple unions were performed after the Church’s 1890 Manifesto had purportedly ended the practice of plural marriage. In this counter-history, most Mormons made another great migration in 1900 to settle in Mexico, where the Church became headquartered. How willingly, he appears to be asking, would we and our ancestors have given up everything one more time?

Having stuck in there himself as an active Mormon for more than half a century (including two full-time missions with his wife), Christmas feels comfortable enough to ponder in print the mysteries of sacred underwear, wondering

to what General Authority or

Authority’s wife), did he owe thanks

for his two-piece garments?”

The old “one-piecers” had beaten a

retreat from wrist to upper-arm, and from

ankle to knee—but now, here came

this slice—across the middle.

God was behind it—but why? All he

knew was his wife loved them.

He remembered shopping for garments

in 1964 in Pocatello, Idaho,

when you could buy them at Penney’s.

In one of the aisles a portable hi-fi

was playing The Beatles first album: “Roll

over, Beethoven”—stuff like that.

It was the first time he’d heard them,

and he was enchanted. He prolonged his

purchase, because there was something

in the air. (It was radical change;

but he didn’t see it coming, and had

no inkling it would go so far.) (7)

Some readers may judge R. A. Christmas for his seeming irreverence; others will bless this book for its invitation to take a good, long look in the mirror and laugh.

R. A. Christmas. The Kingdom of God or Nothing! Durham, N.C.: Lula Press, 2008. 60 pp. $ 11.00

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue