Articles/Essays – Volume 49, No. 2

The LGBTQ Mormon Crisis: Responding to the Empirical Research on Suicide

Introduction

The November 2015 LDS handbook policy change that identified members who participate in same-sex marriages as “apostates” and forbade children in their households from receiving baby blessings or baptisms sparked ongoing attention to the topic of LGBTQ Mormon well-being, mental health, and suicides. When talking about LGBTQ youth suicides in our LDS community, we need to make sure we are working with the best empirical evidence available, and we need to be certain that the evidence presented is being interpreted correctly. Otherwise poor government policies will be put in place that may offer no benefit or might even exacerbate the problem. This article will look at five questions that need to be considered in this very important public health issue:

- What direct empirical evidence is available regarding LGBTQ youth suicides?

- What is the indirect evidence?

- What is the anecdotal evidence?

- What conclusions can we draw taking into account the limitations of empirical, inferred, and anecdotal evidence?

- What preventive measures should be implemented while we are waiting for more definitive empirical evidence?

What Is the Direct Empirical Evidence

LGBTQ teens are twice as likely to attempt suicide as straight adolescents, according to the Centers for Disease Control.[1] Others have found that these youth are also more likely to contemplate as well as attempt suicide, although they also point to other factors that also relate to the risk of suicide including depression, substance abuse, and others.[2]

It is essential to acknowledge that suicidality is multifaceted, and being gay, lesbian, or transgender is not necessarily in all cases risk factors for suicide attempts. In fact, as we will discuss later in this article, LGBTQ people who have supportive families and communities are not at increased risk of poor mental health outcomes. Risk factors for suicide among LGBTQ teens are actually similar to risk factors for suicide among all teens and include hopelessness, major depression symptoms, impulsivity, past suicide attempts, conduct disorder (i.e. destructive, aggressive, deceitful behaviors, and violation of rules), victimization, perceived family support (support from peers does not have the same impact), and the recent suicide or attempted suicide of a family member or close friend. Some of these risk factors, such as family rejection or victimization, might disproportionately impact LGBTQ teens, which would explain their overall higher rate of suicide attempts.[3]

Family rejection leads to an eight-fold risk of suicide attempts among LGBTQ teens. The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) has done some excellent research showing that there is an exponential risk of suicide for LGBTQ teens who come from families that show “rejecting behaviors” such as not addressing issues of bullying and exclusion or endorsing attitudes that exclude members of the LGBTQ community.[4] They even studied what those rejecting behaviors are, and anyone familiar with the Mormon community would recognize those rejective behaviors as sometimes being common in our communities. (A full list of these “rejecting behaviors” can be found toward the end of this article.) Parents’ rejecting behaviors are often reinforced by local Church leaders and Mormon culture. It is important to note that the risk of suicide remains higher for rejected youth well into adulthood. They also have exponentially higher rates of drug/alcohol use, depression, and HIV infection than youth raised in homes that do not show these rejecting behaviors. The FAP research is in line with other empirical studies that show that many of these risk factors for suicide attempts can be decreased by “family-based interventions that increase support [which] reduce hopelessness and depression symptoms.”[5]

Supportive communities and schools reduce suicide risk among LGBTQ teens. Schools with explicit anti-homophobia interventions such as gay-straight alliances (GSAs) may reduce the odds of suicidal thoughts and attempts among LGBTQ students. A study by the University of British Columbia using data from the 2008 British Columbia Adolescent Health Survey showed that “LGBTQ youth and heterosexual students in schools with anti-homophobia policies and GSAs had lower odds of discrimination, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, primarily when both strategies were enacted, or when the policies and GSAs had been in place for three years or more.”[6] This study also found that LGBTQ youth in supportive environments experienced fewer suicidal thoughts and attempts by about two-thirds. Interestingly, suicidal thoughts and attempts also dropped among heterosexual boys and girls in the schools that put these policies into place.

Mark Hatzenbuehler of Columbia University polled 30,000 Oregon teens and found that those living in supportive communities were 25 percent less likely to attempt suicide compared to teens in more hostile communities (as evidenced by the presence or absence of anti-discrimination policies or anti-bullying programs). “The results of this study are pretty compelling,” Hatzenbuehler said in a statement. “When communities support their gay young people, and schools adopt anti-bullying and anti-discrimination policies that specifically protect lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth, the risk of attempted suicide by all young people drops, especially for LGB youth.”[7]

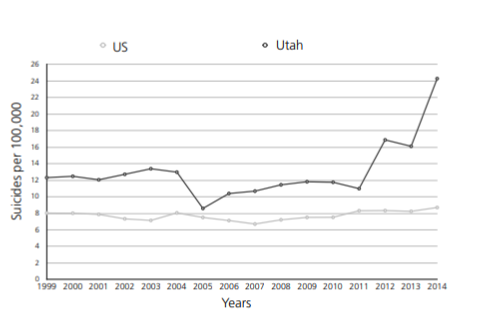

Suicides have doubled in the past four years, becoming the number one cause of death among Utah teens. Suicide is the number one cause of death of all Utah youth; this is not the case nationally, and Utah consistently ranks above the national average for suicide deaths.[8] While Utah suicide rates are higher than the national average, they are, nevertheless, generally in line with the other Rocky Mountain states. Though this is true, it is alarming that the teen suicide rate in Utah has doubled since 2011, which is not something we have seen in the other Rocky Mountain states, nor in Alaska. Figure 1 [Editor’s Note: See PDF, p. 5, for Figure 1] displays suicide rates (per 100,000) from 1999 to 2014, comparing the fifteen- to nineteen-year-old age group in Utah with the same age group in the United States as a whole as reported by the Centers for Disease Control.[9]

Summary. A clear body of research shows an elevated risk of suicide among LGBTQ teens nationally and indicates the major risk factors for suicide and other poor outcomes. There is no reason to believe that the LDS community is immune to this. Based on this alone, we need to consider that we have a suicide problem in our community. Analysis of the data suggests that the problem is worse in LDS communities than the national average. The youth suicide rate in Utah is the first statistic that implies this. Although the suicide rate is elevated throughout the Intermountain West,[10] no other states have seen the doubling in teen suicides that Utah has had in the past four years. Why is youth suicide in Utah so much higher than the national average? Since LGBTQ issues may be a large factor impacting teen suicides, it would be irresponsible not to address these issues locally, especially when the suicide problem is so acute in Utah, where the highest concentration of Mormons is found. Meanwhile, studies have shown the risk factors for suicide. However, protective factors have not been studied as extensively or rigorously as risk factors.[11]

What is the Direct Evidence?

Mental health outcomes and mortality rates for LGBTQ are the same as non-LGBTQ people in communities that are friendly to LGBTQ issues. In a 2013 study, Hatzenbuehler, et al. found that in communities that are highly prejudiced against sexual minorities, the life expectancy of sexual minorities is twelve years shorter when compared to low-prejudice communities.[12] Causes of the twelve-year difference are not limited to mental health and suicide; they also include homicide/violence and cardiovascular disease. They also report an eighteen-year difference in the average age of completed suicide among LGBTQ people in high-prejudice communities when compared to low-prejudice communities. We can infer from these findings that an elevated risk of suicide correlates with the elevated risk of mental illness prevalent among LGBTQ people living in communities that are hostile to LGBTQ. In a report of the study published in U.S. News and World Report, Hatzenbuehler concludes: “The results from the current study provide important social science evidence demonstrating that sexual minorities living in communities with high levels of anti-gay prejudice have increased risk of mortality, compared to those living in low-prejudice communities.”[13]

Meanwhile, there is actual evidence that homosexuals are not at any increased risk of mental illness when they are in a less homophobic community. A study published in Psychosomatic Medicine by researchers at the University of Montreal (lead author Robert-Paul Juster) shows that “as a group, gay and bisexual men who are out of the closet were less likely to be depressed than heterosexual men and had less physiological problems than heterosexual men.”[14] A Concordia University doctoral thesis in clinical psychology investigated and examined environmental risks and protective factors that counter-balance the severe mental illnesses that LGBTQ youth have and the role of cortisol, which is a hormone that is released in situations of stress leading to physical and mental health consequences. The author found that LGBTQ youth have abnormal levels of cortisol (compared to their heterosexual peers), which contributes to rates of mental illness and then influence rates of suicide.[15]

New research is also emerging that shows transgender people also have normal mental health when they are in a supportive environment from an early age. A study out of the University of Washington published in March 2016 showed that prepubescent children who are living openly as transgender with the support of their families fare very well and have no increase in depression or anxiety compared to other children. This is a striking contrast to prior studies on transgender people that have shown higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide. The big difference is being able to live openly at a young age with parental support.[16]

LGBTQ youth are more likely to be homeless. National studies show an exponentially higher risk of homelessness among LGBTQ teens. A 2013 National Conference of State Legislatures report found that between 20 and 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ.[17] Providers and outreach workers in Utah have noticed that this also applies to Utah, and they have noted a high rate of LGBTQ teens from LDS families among the homeless teens they serve. A 2014 Salt Lake Tribune article noted: “More than 5,000 youth are estimated to experience homelessness in Utah per year. Of these, at least 40 percent are LGBT and the majority are from religious and socially conservative families, with 60 percent from Mormon homes.”[18]

Utah’s doubling of teen suicides in the past four years corresponds to increased rhetoric by the LDS Church against same-sex marriage. As noted above, data from the CDC show that suicides in the fifteen to nineteen age range in Utah have doubled since 2011. While Utah doubled its rate of suicides among teens, the rest of the country did not see a substantial increase in their suicide rate (see Figure 1). Suicide has become the leading cause of death in this age group in Utah.[19] Of course, correlation does not prove causation, but it is important to look at correlating factors to determine which of these might explain causation. The time frame for this doubling of teen suicides does correspond to an increased focus in the media on LGBTQ issues, especially in Utah as the debate on same-sex marriage played out.[20] That clearly led to a backlash, including frequent Church statements criticizing same-sex marriage or the LGBTQ community. It stands to reason that these statements have reinforced conflicts within congregations and families over the issue and has unleashed an increase of demonstrated homophobia and anti-LGBTQ feelings within families. It can easily be inferred that this chain of events exacerbated family rejection of vulnerable LGBTQ teens, thereby increasing their risk of suicide attempts as described earlier.

Most LGBT youth and young adults lose the protective effects of belonging to a religious community. A study of Mormon men in Utah shows that leaving the Church puts one at a much higher risk of suicide. A 2001 study looked at completed suicides of Utah men between the ages of fifteen and thirty-four and cross-referenced their activity in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The study’s authors estimated the individual’s degree of church activity by observing the level of priest-hood ordination at the date of the suicide. They concluded that leaving the Church raised the risk of suicide among all young men.[21] We also know that LGBTQ people leave the Church or are invited to leave at very high rates (36.3 percent inactive; 25.2 percent resigned; 6.7 percent excommunicated; 3.0 percent disfellowshipped).[22] From these studies we can infer that these LGBTQ young men are among those who have a substantially higher risk of suicide when they lose the protection that membership in a religion provides against suicide risk. If so, then bishops, stake presidents, and family members have reason to worry when an LGBTQ person stops attending church. It seems that the effect of religion on suicidal ideation is mixed. However, a recent study suggests that religion may serve as a protection against suicide attempts, even when LGBTQ people have “internalized homophobia.”[23] This same study shows once again that maturing in a religion increases the risk of suicide among those who leave. It can thus be inferred that LGBTQ people are placed at higher risk when they feel unwelcome in their religious communities and end up losing the protection of religious involvement.

In sum, “it may seem counterintuitive that when individuals chose to leave their religion in order to experience more self-acceptance that they inadvertently experience more risk for suicide.”[24] These studies, observations, and data do not directly answer our questions about LGBTQ suicides, but they raise concerns about the well-being, mental health, and suicide-risk among our LGBTQ teens and young adults. In the above cases, the inferred conclusions are compelling and point to a broad range of evidence that demonstrate a serious problem in our community.

What Is the Anecdotal Evidence?

Anybody who knows a substantial number of LGBTQ people with LDS backgrounds will be astounded by how many have attempted suicide. Those who are in a particular position of outreach, such as the leadership of Affirmation, Wendy and Thomas Montgomery, or Carol Lynn Pearson, have also reported being overwhelmed by the consistent pattern of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicides among LGBTQ people from Mormon backgrounds, particularly among youth and young adults. Clinicians who have worked with teens in Utah including, clinicians from LDS Family Services, have noticed the high rate of despair and suicidal thoughts among LGBTQ teens (as well as adults).[25] Further, polling of USGA (a support organization for LGBTQ BYU students) showed a very high rate of suicide attempts among its members.[26] Informal polling of LGBTQ youth on a Facebook group for LDS LGBTQ youth has also revealed the ubiquitous nature of suicidal thoughts among our LGBTQ Mormon youth.[27]

What Conclusions Can We Draw?

When we put these data together, it is impossible to know exactly how many suicides there are among Mormon youth and how many of these are related to LGBTQ issues. In large part this is because data collected by the government on deaths, including suicides, do not generally indicate the sexual orientation of the deceased.[28] Despite this fact, we have described above some compelling evidence that allows us to conclude that there is a significant problem and make some reasonable inferences. The direct empirical evidence alone is enough to merit a public health response.

The indirect evidence is also compelling because there are such close correlations between suicide and mental illness/mood disorders, as well as homelessness in general, and LGBTQ people have a higher prevalence of these, especially in communities that are unfriendly to LGBTQ issues and concerns. We can reasonably infer from this that LGBTQ suicides are higher in these communities.

In the case of LDS youth suicides, we are forced to pay attention to both indirect evidence and anecdotal evidence because it is so difficult to gather empirical evidence about any suicide cohort because of the stigma associated with it as well as the intense grief experienced by these families. Some families are in denial that their family member is LGBTQ. Furthermore, those youth at highest risk are often the same youth who will hide their sexual orientation, so the family may not even be aware. As one Provo police officer put it: “They don’t leave a note saying they died by suicide because they are gay.”[29] It is often difficult to tell if an accidental death is actually a suicide and so those will be missed by any inquiry. Investigating whether sexual orientation is a factor in suicide is clearly complicated, and state agencies in Utah (and other states) have been reluctant to do so.

Normally we should be reluctant to make decisions based on anecdotal evidence alone. However, when the various pieces of evidence (anecdotal, direct, and indirect) provide a highly compelling picture that strongly suggests that lives are at stake (as can happen in any public health crisis), it is critical to be proactive.

Presently, a public health action is even more compelling because we have identified preventive measures that are low cost, low risk, and have already been shown to be effective. Currently the problem is not a lack of evidence, but quite simply a lack of will. We have sufficient direct evidence that is strengthened by indirect evidence and reinforced by anecdotal evidence. The case is strong. Our inability at this time to provide conclusive evidence (again, given that the government does not track the sexual identity of suicide or other mortality indicators) does not diminish our responsibility to take measures to decrease suicides by decreasing suicide attempts—and that is within our reach.[30] It is also within our reach to address the depression, despair, and isolation that afflict our LDS LGBTQ youth.

Discussion: What Drives Despair?

Depression and mood disorders play a role in many if not most suicide deaths or attempts. But what can we look at from a community stand-point? What are the factors that put people at risk and then put some of them over the edge? Neuroscientist Michael Ferguson pointed out in a recent podcast interview that “as social beings when you’re shunned or you’re excommunicated or you’re rejected from your primary community of attachments, your body experiences [symptoms] like you’re preparing to die.”[31] Humans are social creatures and surviving without our most important social connections was historically impossible for our ancestors. Being cast out was literally deadly. To a social animal such as a human, there are few things worse than ostracism.

Consider seeing through the eyes of an LGBTQ teen. Their emergent sense of self as an LGBTQ person often triggers fear of losing their family if their family finds out. Much of what they hear at church inculcates fear that they will not be part of their family in eternity. An entire future is mapped out for them that they see as increasingly impossible to fit into. If they have any gender-nonconforming behaviors or traits, they face bullying at school and at church, and they often do not receive support from their parents around the issue because they are too frightened to talk to them. Parents sometimes reinforce this at home by making homophobic comments, which confirm the child’s fears that they will lose their family if they come out, and that they might even lose their shelter and education by being kicked to the streets.

Meanwhile, hostile messages surround them at church, school, and home. Like every teen, they start to develop feelings and dreams of love and companionship, but then they receive the message that their desires are evil, and that in order to be accepted they have to follow a path that feels impossible for them. Most LGBTQ Mormons have this experience to varying extents. Many of them work their way through it and survive. However, many have other problems, such as depression or poor family structures. The despair often leads them to risk-taking behaviors such as substance abuse or unprotected sex. These factors stack up and multiply their odds of having a suicide attempt or other dangerous behavior.

In the past, there were messages from LDS Church leaders that could reasonably be interpreted by some as indirectly encouraging suicide. For example, in 1981 President Marion G. Romney wrote that “some years ago the First Presidency said to the youth of the Church that a person would be better dead clean than alive unclean.” He then shared a memory of his father telling him before he boarded the train to leave on his mission: “When you are released and return, we shall be glad to greet you and welcome you back into the family circle. But remember this, my son: we would rather come to this station and take your body off the train in a casket than to have you come home unclean, having lost your virtue.”[32]

Other statements could be interpreted as encouraging bullying or violence against LGBT individuals. For example, in the 1976 priesthood session of general conference, Elder Boyd K. Packer expressed his hearty approval of a missionary who punched his [presumably homosexual] companion to the floor in response to unwanted sexual advances. He said: “Somebody had to do it, and it wouldn’t be well for a General Authority to solve the problem that way. I am not recommending that course to you, but I am not omitting it. You must protect yourself.”[33]

While messages like this from the General Authorities have thankfully ceased, they remain part of the cultural memory among older members and can still routinely make their way into sacrament meeting talks, lessons, and advice and counsel from priesthood leaders. LGBTQ youth absorb these messages and may attempt to kill themselves because they conclude that they do not have a future worth living or because they believe that this was what their parents would prefer.

To be clear, we are grateful that rhetoric surrounding LGBTQ issues has improved in many ways over the last several years.[34] This positive rhetoric is often difficult to fully internalize (or even perceive as genuine), however, in the context of the other more exclusionary messages that Church leaders continue to send, the most recent and significant of which is the November 2015 handbook policy change that defined Church members who enter into same-sex marriages as “apostates” and forbade baby blessings and baptism to children living in such situations.[35] This exclusionary messaging was only exacerbated when President Russell M. Nelson declared in January 2016 that the handbook policy change was the Lord’s will as revealed to his prophets.[36]

Since the majority of LDS families are indeed strong families whose homes are full of love, parents often assume that they would know if their children were feeling conflicted. It is difficult for them to imagine that their child would be afraid to disclose feelings of despair, isolation, or thoughts of self-harm. This is a prevalent assumption of parents, especially those who focus so much time and energy on their families. But many of these loving parents are sending rejecting messages long before they realize that their child might be LGBTQ. As a colleague of ours put it:

Having a loving family isn’t enough. Parents need to actually sit down with their kids throughout their youth and specifically say “We will love and be proud of you if you marry a boy or a girl or don’t marry at all. Though missions are important, we know that isn’t always possible for everyone and that’s okay too. We will stand up for you and your choices. We will help you the best we know how, no matter what; even if we don’t understand at first. If at some point your life goals feel different than what we currently know about you, we want to discuss that together and understand what your life direction means to you personally. Not being exactly like us should never cause you to fear us being disappointed in you.” Until that conversation is being had in the homes of every LDS family, we will continue to see LGBTQ people suffer in isolation.[37]

Another important source of despair for LGBTQ youth is the political culture in Utah, which is in many ways a reflection of the LDS Church and Mormon community. The Mormon majority in the Utah legislature is widely perceived to be responsive to what the Church leaders support and the Church regularly influences legislation openly, such as when they supported a compromise that allowed passage of a statewide anti-discrimination bill that gave substantial exemptions based on religion.[38] We also saw the Utah State Senate in March 2016 shoot down a proposal to modify the state’s hate crimes laws to include protections for LGBTQ individuals after the Church opposed the law.[39]

Meanwhile, the Utah state legislature has taken steps which are not encouraging to LGBTQ youth. Utah, along with seven other US states, has a ban on teachers discussing any LGBTQ issues in public schools.[40] This makes it very difficult for schools to adopt measures that will help combat bullying and create a safe learning environment for LGBTQ youth. Marian Edmonds-Allen, Utah’s leading advocate for LGBTQ youth, laments the situation in our schools: “State school board guidelines that prohibit ‘the advocacy of homosexuality’ are directly contributing to risk of suicide for youth, both LGBT and straight. Gay-straight alliances, which have been shown to provide a 50 percent reduction in suicide risk for males, both GBT and straight, are becoming even more rare in Utah.”[41]

As the law now stands in Utah, school counselors are not allowed to address relevant issues with LGBTQ youth who report suicidal thoughts, nor are they allowed to give parents helpful information/resources or even explain the problem when their child is feeling rejected due to their sexual orientation or gender identity.[42] One can see how this puts undue stress on LGBTQ teenagers who are left with nowhere to turn for support.[43]

Even more alarming is the glaring lack of resources for homeless teens. Like the rest of the nation, a disproportionate number of homeless teens in Utah are LGBTQ. Whether gay or straight, their lives in the streets and canyons of Utah are bleak. Until one year ago, there was not a single shelter bed available for these youth, which number up to 1,000 at any point in time. Even now there is only one shelter, and it can house only fourteen youth. Laws that supposedly protect parental rights have made it impossible for any law-abiding citizen to offer shelter to any of these children, which means that to survive these youth often have had to turn to prostitution or exploitation by adults. Drugs become an all-too-common escape from their bleak existence, further increasing their vulnerability and dependence upon their exploiters.

Discussion: Did the New LDS Handbook Policy Impace Suicide Numbers?

In the aftermath of the November 2015 handbook policy change (referred to previously) there were significant anecdotal accounts of increased suicide among LGBTQ Mormon youth.[44] This led many to draw direct causal connections between the two events, arguing that the handbook policy change directly caused several dozen youth suicides in the weeks and months that followed. It is important to remember, though, that there was already a major problem with suicide (as well as depression, homelessness, suicide attempts, and despair) among LGBTQ Mormons before the recent policy was revealed. We argue that a better question to ask would be: Are further rejection and homophobia in our communities increasing depression and despair and consequently intensifying the conditions that contribute to the elevated suicide rate in our community?

As stated above, people in positions of outreach such as the Affirmation leadership and the Mama Dragons leadership found themselves dealing with LGBTQ people in distress and often found themselves spending late nights consoling people who were struggling with suicidal feelings. Due to her high visibility in the media, Wendy Montgomery had already had a constant stream of LDS people reaching out to her around this issue to tell her their stories, seek support, and find resources. After the policy was revealed in November, however, she started getting more and more reports from LDS people reporting an LGBTQ family member had committed suicide. She eventually added up these informal reports and found that there were thirty-two deaths from suicide reported to her between November 6, 2015 and January 17, 2016 (the number rose to thirty-four later that month). When John Gustav-Wrathall, the president of Affirmation, reported Montgomery’s numbers on Affirmation.org,[45] a flury of media attention and debate arose.[46]

The data reported by Wendy Montgomery seem confusing because, while she did get a high number of reports of suicide since November 6, it is hard to square these numbers with the state of Utah, which reports that there were only ten suicides in Utah in November and December of 2015 in the fifteen to nineteen age range.[47] We have to be aware that the state will always underestimate actual suicides for several reasons, especially because it will not consider an overdose or an accident a suicide, even though overdoses and accidents are both very common ways of attempting/completing suicide. The Utah numbers also did not include suicides from out-of-state, outside of the fifteen to nineteen age range, or from January. Therefore, the number of youth and young adults suicides is very likely higher than ten. Since the reports sent to Wendy Montgomery were not solicited, precise statistical information is not possible. She has admitted that the reports were not always precise and did not always state when the suicide took place, so it is possible that some of them took place prior to the policy change, factors that may also contribute to the discrepancy.

In sum, there is no direct empirical evidence that indicates that the handbook policy change actually increased Mormon LGBTQ youth suicides. The other direct, indirect, and anecdotal evidence that we have discussed, though, are compelling and certainly strongly suggest a link between these things. It is not difficult to imagine that the impact of this policy change will continue to be felt strongly by LGBTQ Mormons for the foreseeable future.

As problematic as the policy is in our view, we believe that it is also misguided to focus exclusively on the policy change as the primary causal factor of LGBTQ marginalization in the Mormon community. Instead, we should address all of the factors that lead to the marginalization and family rejection of our LGBTQ youth. Focusing on the policy while ignoring these other factors, would do a disservice to the individuals we are trying to protect. Even if the policy exacerbated the problems facing LGBTQ Mormons, the primary problems have been in place for a very long time.

What Can Be Done?

What the existing research has clearly shown is that the single largest factor contributing to the mental and emotional health of young LGBTQ people is family acceptance versus rejection. The Family Acceptance Project has specifically identified “rejecting behaviors” that are associated with mental and emotional harm to LGBTQ individuals. We would do well to ask ourselves if our families, wards, or communities might be doing any of the following:

- Not allowing or strongly discouraging a youth from identifying themselves as LGBTQ.

- Not allowing their child to socialize with other LGBTQ youth.

- Not allowing their child to participate in supportive organizations that will help the youth cope, such as a GSA.

- Not addressing bullying that their children face around being per-ceived as LGBTQ.

- Not protecting their LGBTQ child against derisive comments by uninformed relatives or family friends.

- Engaging in derisive comments about LGBTQ people or demonizing of LGBTQ people.

- Not providing a family climate where a child feels safe to come out to their parents.

- Endorsing statements or comments that make a child fear they will be kicked out of their home or will lose their families if they come out.

The most effective preventions are cheap and easy. We need to educate and support parents and we need to empower our schools to address the needs of our youth. Parents are eager and willing to do what is best for their children. They need to have access to this helpful information through bishops and auxiliary leaders, through mental health providers, and through school counselors. Training needs to happen. Barriers to action need to be removed.

What Should the State Do?

We believe that the state should take more leadership on the issue of LGBTQ and homeless youth. It should participate in efforts to track suicides and suicide attempts and study contributing factors. The state of Utah specifically should lift the “gag rule” so that LGBTQ issues can be discussed in schools and should require schools to adopt anti-bullying programs that have been proven successful in other school districts. It should remove any barriers and promote the creation of school-based GSA (Gay-Straight Alliance) clubs, which have a proven benefit for all students (not just the LGBTQ students). It should seriously address youth homelessness and invest in adequate shelters and remove legal barriers that keep agencies and outreach workers from helping these teens.

What Should the Church Do?

We are going to leave this up to the reader. We have identified the problem. The Church’s role in both the way that LGBTQ issues are handled in Mormon practice, policies, doctrines, and culture, as well as in the legislative process in Mormon-dominant communities, is evident. The Church’s influence in the messages that go to wards and communities about LGBTQ people is, likewise, evident. We hope that Church leaders and members alike will consider the consequences of their positions and rhetoric about LGBTQ issues and find ways to satisfy theological concerns without contributing to the despair and tragedies playing out in the lives of our children.

Conclusion

Any discussion of this issue should take into account whether we are helping or exacerbating the problem. In our opinion, this recent discussion has brought much-needed attention to the issue. Sometimes the discussions have been counter-productive, however. We should not let our focus on one single event, such as the new exclusionary handbook policy, distract us from the numerous issues that lead to distress among our LGBTQ youth. We need to accept that the data we have so far do not allow us to precisely estimate the number of youth suicides driven by the Church’s positions and rhetoric on LGBTQ issues, but we also need to recognize that the evidence points to a serious problem. It also points us toward solutions that are effective and inexpensive.

Furthermore, we should be careful to follow proven guidelines about how to discuss suicide without contributing to suicide contagion. Suicide contagion or “copycat suicide” occurs when one or more suicides are reported in a way that contributes to another suicide.[48] Suicide contagion is a real problem when suicides become high profile. We can and must discuss suicide among our youth, but we need to do it responsibly. We refer readers to ReportingOnSuicide.org for guidance on how to discuss the issue in our online as well as personal conversations. We also recommend resources such as the Family Acceptance Project, I’ll Walk With You, and Affirmation.

Finally, we issue a plea for Church members to be a voice for compassion in their individual wards. Speaking out requires courage, but it also decreases pain and saves lives. You may never know who was saved because of something you said or something you did. But it is important to take a stand, speaking and acting with acceptance, understanding, and love. We have an illness. We have a problem. Let’s implement the cure.

Author’s Note: a previous version of this article originally appeared as a blog post by the same name on Rational Faiths, February 25, 2016. Interested readers are invited to see the full blog post since the appendix includes detailed summaries and excerpts of the various studies cited in this article. We extend our sincere appreciation to the following people for providing resources, information, and insights: Dr. Mikle South, Rev. Marian Edmonds-Allen, Kendall Wilcox, Thomas Montgomery, Wendy Montgomery, Lori Burkman, and John Gustav-Wrathall. We especially recognize and thank the late Dr. Phil Rogers for his generous assistance gathering data from the CDC website and providing us with much of the research discussed in this article.

Editor’s Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health.”

[2] Stephen T. Russell and Kara Joyner, “Adolescent Sexual Orientation and Suicide Risk: Evidence from a National Study,” American Journal of Public Health 91, no. 8 (2001): 1276–81; Arnold H. Grossman and Anthony R. D’Augelli, “Transgender Youth and Life-Threatening Behaviors,” Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 37, no. 5 (2007): 527–37.

[3] Brian Mustanski and Richard T. Liu, “A Longitudinal Study of Predictors of Suicide Attempts among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 42, no. 3 (2013): 437–48.

[4] Caitlin Ryan and Robert A. Rees, Family Education LDS Booklet (San Francisco: Family Acceptance Project, 2012).

[5] Mustanski and Liu, “A Longitudinal Study of Predictors,” 437–48.

[6] Tracy Tang, “Gay-Straight Alliances in Schools Reduce Suicide Risk for All Students,” University of British Columbia, Jan. 20, 2014.

[7] Jennifer Welsh, “Homosexual Teen Suicide Rates Raised in Bad Environments,” LiveScience, Apr. 18, 2011.

[8] Utah Department of Human Services, “State Suicide Prevention Programs,” Oct. 2015.

[9] At the time of this writing, the years 1999 to 2014 were publicly available. We do not see the same doubling of suicide rates in Utah among those aged twenty to twenty-four (although it is higher than the national average in that age cohort), indicating that the rapid increase seems to be limited to high school–aged youth.

[10] Mikle South, “Op-ed: Misuse of Utah Suicide Data Makes It Harder to Address,” Salt Lake Tribune, Feb. 6, 2016.

[11] Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, “Suicide: Risk and Protective Factors,” Aug. 28, 2015.

[12] Mark L. Hatzenbuehler, Anna Bellatorre, Yeonjin Lee, Brian K. Finch, Peter Muennig, and Kevin Fiscella, “Structural Stigma and All-Cause Mortality in Sexual Minority Populations,” Social Science & Medicine 103 (2013): 33–41.

[13] Shannon Firth, “Research: Anti-Gay Stigma Shortens Lives,” U.S. News and World Report, Feb. 19, 2014.

[14] Jason Koebler, “Study: Openly Gay Men Less Likely to Be Depressed Than Heterosexuals,” U.S. News and World Report, Jan. 29, 2013.

[15] Sylvain-Jacques Desjardins, “Physiological Impacts of Homophobia,” EurekAlert!, Feb. 2, 2011.

[16] Kristina R. Olson, Lily Durwood, Madeleine DeMeules, and Katie A. McLaughlin, “Mental Health of Transgender Children Who Are Supported in Their Identities,” Pediatrics, Mar. 2016.

[17] “Homeless and Runaway Youth,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Apr. 14, 2016.

[18] Peggy Fletcher Stack. “Program Aims to Stop Suicide, Homelessness in LGBT Mormon Youth,” Salt Lake Tribune, Mar. 15, 2014.

[19] “State Suicide Prevention Programs,” Utah Department of Human Services, Oct. 2015.

[20] See Google Trends in both United States and Utah, specifically from 2007 to present on LGBTQ topics: https://www.google.com/trends/.

[21] Sterling C. Hilton, Gilbert W. Fellingham, and Joseph L. Lyon, “Suicide Rates and Religious Commitment in Young Adult Males in Utah,” American Journal of Epidemiology 155, no. 5 (2002): 413–19.

[22] John P. Dehlin, Renee V. Galliher, William S. Bradshaw, Daniel C. Hyde, and Katherine Ann Crowell, “Sexual Orientation Change: Efforts Among Current or Former LDS Church Members,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 62, no. 2 (2014): 95–105.

[23] 23. Jeremy J. Gibbs and Jeremy Gladbach, “Religious Conflict, Sexual Identity, and Suicidal Behaviors among LGBT Young Adults,” Archives of Suicide Research 19, no. 4 (2015): 472–88.

[24] Gibbs and Gladbach, “Religious Conflict,” 11.

[25] Matt McDonald, “LDS Leader’s Comments about Suicides after Policy Change Angers Mama Dragons,” Fox 13, Salt Lake City, Feb. 16, 2016; Jennifer Napier-Pearce, “Trib Talk: Suicide in the Wake of LDS Church’s Policy on Gay Couples,” Salt Lake Tribune, Feb. 1, 2016.

[26] “LGBT Suicides at BYU: Silent Stories,” Understanding Same-Gender Attraction (USGA), Jan. 29, 2016; “‘Just Be There’: A Message of Suicide Awareness and Prevention,” No More Strangers, Oct. 10, 2013; see also Annie Knox, “BYU ranked among the least LGBT-friendly campuses,” Salt Lake Tribune, Aug. 10, 2015.

[27] Of course, anecdotal evidence is not generalizable because of its non-representative sample bias, prejudice, or any number of other factors. However, when the anecdotal evidence becomes massive (as it has to those of us who work directly with LGBTQ Mormons around this issue), then it strongly suggests that something wider may be happening.

[28] Mike Barker has asked a suicidologist, several LGBTQ advocates, two forensic specialists (none of these people questioned are from Utah), and at least one concerned Utah lawmaker if there are any states that perform what is called a “psychological autopsy” with regard to the deceased’s sexuality as part of the suicide investigation. The answer has been no. In an email, Barker received the following response from The Trevor Project when he inquired about state agencies tracking the sexual orientation of those who have died by suicide:

“This project is currently in the pilot phase. The people involved with conduct-ing the National Violent Death Reporting System have developed a protocol for death investigators to determine the sexual orientation and gender identity of the deceased. They are just beginning training the death investigators on this protocol in the first pilot jurisdiction: Las Vegas.”

[29] Personal correspondence by one of the authors with a direct family member who wishes to remain anonymous.

[30] Ann P. Haas, et al., “Suicide and Suicide Risk in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations: Review and Recommendations,” Journal of Homosexuality 58, no. 1 (2010): 10–51.

[31] Fausto Fernos, “FOF #2279 – A Tale of Two Mormons,” Feast of Fun, podcast audio, Jan. 27, 2016.

[32] Marion G. Romney, “We Believe in Being Chaste,” Ensign (Sept. 1981).

[33] Boyd K. Packer, “Message to Young Men,” Oct. 1976. It is interesting to note that this is the only talk in the conference whose transcript is not available; only the audio/visual is available.

[34] Examples include the mormonsandgays.org website as well as Elder Oaks’s October 2012 general conference address entitled “Protect the Children,” in which he stated: “Young people struggling with any exceptional condition, including same-gender attraction, are particularly vulnerable and need loving understanding—not bullying or ostracism.”

[35] Sarah Pulliam Bailey, “Mormon Church to Exclude Children of Same-Sex Couples from Getting Blessed and Baptized until They Are 18,” The Washington Post, Nov. 6, 2015.

[36] Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Mormon gay policy is the ‘will of the Lord’ through his prophet, senior apostle says,” Salt Lake Tribune, Jan. 10, 2016.

[37] Personal correspondence between Lori Burkman and the authors, Feb. 2016.

[38] Laurie Goodstein, “Utah Passes Antidiscrimination Bill Backed by Mormon Leaders,” The New York Times, Mar. 12, 2015.

[39] Jennifer Dobner, “Senate Kills Hate-Crimes Bill; LGBT Advocates Blame Mormon Church,” Salt Lake Tribune, Mar. 2, 2016.

[40] “State Maps,” Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

[41] Marian Edmonds-Allen, “Suicides or Not, LDS Is Harming LGBT Youth,” Advocate, Feb. 3, 2016.

[42] Utah Code, § 53A, 13-302.

[43] See Haas, et al., “Suicide and Suicide Risk.”

[44] Mark Joseph Stern, “The Tragic Results of the Mormon Church’s New Policy Against Gay Members,” Slate, Feb. 8, 2016; Mitch Mayne, “New Mormon LGBT Policy: Putting Already Vulnerable Youth at Even Greater Suicide Risk?,” Huffington Post, Jan. 28, 2016; Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Suicide Fears, If Not Actual Suicides, Rise in Wake of Mormon Same-Sex Policy,” Salt Lake Tribune, Jan. 28, 2016.

[45] John Gustav-Wrathall, “Our Lives Are a Gift—To Us and the World,” Affirmation, Jan. 2016.

[46] See for example Stack, “Suicide Fears”; Tad Walch and Lois M. Collins, “LDS Church Leaders Mourn Reported Deaths in Mormon LGBT Community,” Deseret News, Jan. 28, 2016.

[47] Stack, “Suicide Fears.”

[48] See reportingonsuicide.org and lgbtmap.org.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue