Articles/Essays – Volume 48, No. 3

The Last Memory: Joseph F. Smith and Lieux de Mémoire in Late Nineteenth-Century Mormonism

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Introduction

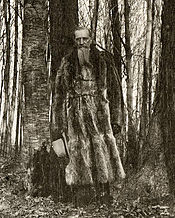

On the day after Christmas in 1915, Joseph F. Smith (JFS), then president of the LDS Church and less than three years away from his own death, spoke to a group of people in the Eleventh Ward meetinghouse in Salt Lake City. The past was always important to JFS and as he got older he found himself, usually at the behest of other Latter-day Saints, giving voice to his memories with increasing frequency. JFS accepted the invitation to speak on this day because “[s]ome of the good folks present are anxious to hear something about my early experiences.”Although few things are more common than an old man telling stories about his youth, this event, and the dozens like it that JFS participated in during the last years of his life, was about far more than personal memory. These “good folks” wanted to hear something about the early experiences that formed the basis of their own communal identity. JFS represented a rapidly fading live link to a mythical past, a catalyst that could, if primed correctly, reanimate the traumas of Missouri and Nauvoo for a generation that did not know them. JFS did not disappoint on this score. He tied himself to the mythic events, he reached back and touched the legendary past, and his audience reached out and touched him. He completed the circuit of collective memory in a way that would soon be impossible.

In this essay, I explore how JFS served as a “site of memory” for late nineteenth-century Mormons and how his own memorial experiences shaped first his personal sense of reality and then the wider Mormon collective memory. The vast majority of the memories shared by JFS were deeply traumatic, not only for him but also for the community of which he was the living symbol.

From the time of his father’s murder, JFS began building a narrative that made both sense of the events and capacitated him in making sense of prospective events in light of that narrative. Theorists of biography have noted this propensity. Leon Edel, perhaps the most influential biographical theorist of the last thirty years, argues that every person has a “personal myth.” What he means by this is that all of us have in our minds a story in which we are the main character. We perceive ourselves as individual beings with boundaries, separate from other beings, a self that has a past and a future. In order to provide meaning to our sensory experiences as individuals, we arrange these experiences mytho logically—as ideology in narrative form. We construct a beginning and we identify moments that, taken together, provide us with a meaningful storyline—our own “personal myths.”

Norman K. Denzin argues that there are two basic types, or genres, of autobiographical stories that individuals tell. One is called “self-stories” and the other Denzin dubs “personal-experience narratives.” Personal-experience narratives are all about group dynamics. They are stories told that “recreate cherished values and memories of a group.” Self-stories, by contrast, are narratives told about the self with no further ambition beyond being a “story of and about the self in relation to an experience.”What makes JFS so interesting from a biographer’s point of view is that his autobiographical anecdotes collapse Denzin’s two categories. JFS’s memories of Nauvoo lie at the exact point where personal experience narratives and self-stories intersect. His personal memories of Hyrum and Joseph Smith, no matter how banal, are self-stories in that they are personal and intimate, but they also function as personal-experience narratives because they touch on the Mormon mythos—the narrative and collective memory of the entire Church.

Dan P. McAdams, a psychologist who has done extensive research on what autobiography can tell us about the psycho logical formation of the self, is a particularly useful resource for trying to tease out meaning from JFS’s reminiscences. Like Edel, McAdams embraces the idea of the personal myth, which he defines as those stories one tells about one’s self whose purpose is to “rearrange the past so that it can be seen to have given birth to the present.”There is constant contact between one’s sense of the past and one’s sense of the present, and each influences the other. McAdams argues that personal myths are thus malleable and are frequently recast “to embody new plots and characters and to emphasize different scenes from the past and different expectations for the future.”The recasting is often tied to the life cycle and most people “make progress over time in the search for unity and purpose as we move from adolescence through adulthood.”

Unfortunately, we have no documents from JFS’s adolescence in which he reminisces about his past. By the time he begins to speak and write extensively and deliberately about his past, he is in late middle-age and his myth has become highly ossified, probably because his life entered a particularly turbulent period in the mid-1880s that lasted for more than twenty years. JFS’s personal myth, grounded in his memories of the Missouri and Nauvoo periods, provided a useful tool in making sense of the difficulties he faced on the polygamy “underground,” his conflicted emotions surrounding the Manifesto of 1890, the humiliation of the Reed Smoot hearings, the “Second Manifesto” of 1904, and the deaths of several of his children. JFS’s memories, constructed to best suit his needs, took the uncertainty out of present trauma by linking it with past trauma. JFS was thus enabled to view the world and life as an integrated whole that cohered around the idea of righteous suffering and living martyrdom.

Sites of Memory

“Memory,” writes historian Geoffrey Cubitt, “is always a view from within a group [whereas] history views groups from the outside.”What Cubitt applies to “groups” may also be applied to specific periods of time viewed within the frame of a shared cultural identity. This is certainly true in the case of LDS views of the pre-Utah period of their history. In this article, I explore how Joseph F. Smith came to embody the “memory” of a time period that was moving very rapidly into “history” for the Latter-day Saints. As JFS grew older, he became a living specimen of what Pierre Nora calls lieux de mémoire, or sites of memory. Nora defines sites of memory as “any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by dint of human will or the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community.”The necessity of these sites is grounded in perceived discontinuities between the present life of a community and its shared historical memory. In Nora’s words,

Our interest in lieux de mémoire where memory crystallizes and secretes itself has occurred at a particular historical moment, a turning point where consciousness of a break with the past is bound up with the sense that memory has been torn—but torn in such a way as to pose the problem of the embodiment of memory in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. There are lieux de mémoire, sites of memory, because there are no longer milieux de mémoire, real environments of memory.

Joseph F. Smith became a site of memory as the nineteenth century aged, the pioneer era slipped away, the founding generation died off, plural marriage was renounced, and Mormons became Americans. JFS was a living conduit to the Smith family, and neither he nor his fellow Mormons ever forgot that. Moreover, by emphasizing the trauma of the Mormon past, JFS was sharing not only the knowledge but also the feeling of the cultural trauma. “I am among,” he reminded his audience, “a very few now living who can speak from their own knowledge of an acquaintance with the Prophet Joseph Smith.”JFS assured the ward members that even though he was only “a child in those days,” he “knew the Prophet Joseph Smith” and “can see him in my mind’s eye just as he seemed to appear to me then.” To hammer home his bona fides as a true acquaintance of Joseph Smith, JFS asserted, “I was just as familiar in the home of the Prophet as I was in the home of my father.”Especially important in the case of JFS was his role as site of memory for the Missouri and Nauvoo periods. Through the application of theoretical models to archival data, this essay presents the complex role that JFS played as the “last memory” of the founding period.

Personal Myth and the Burden of Embodied Collective Memory

Telling stories about the past became a way of life for JFS. As time wore on, two complementary phenomena emerged. First, fewer and fewer people remained who had enjoyed personal acquaintance with Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Second, the passing decades added stature to the two men in the collective memory of the Mormon people. In March 1904, John R. Winder of the First Presidency proposed, “Whereas, nearly sixty years have passed since the martyrdom of the Prophet and Patriarch, Joseph and Hyrum Smith, and no public building or monument has been erected to their memory. Therefore, be it resolved by this general conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that a suitable building or monument be erected to their memory.”The surprisingly late date of such a natural suggestion is probably due to the combined factors of increased Church ability to collect and allocate funds for such a purpose and the ever-dwindling numbers of personal acquaintances of the Smith brothers.

By the early twentieth century, these two trends converged and JFS became the main connection between the Mormons as a whole and their by-now mythic past. But even in his own head, JFS was telling himself stories about who he was and why he was. These stories are evident in the way he responded to crises and to joys. The stories themselves carry worth that goes far beyond what historical truth they may contain. The choices involved in constructing a narrative are not arbitrary and they are not objective descriptions of the passage of time. Hayden White calls this process “emplotment.”French scholar Michel de Certeau observes that there is an important qualitative difference between “lived history” and “history retold.”Retelling history is a narrative process and narrative is “an art of saying . . . an art of thinking and of operating.” This art, de Certeau notes, “produces effects, not objects.”

Not unlike music, the narration of historical events is designed to evoke feeling. Narration is calculated to convey information only secondarily. Its primary purpose is to provide meaning, to give shape and form to the chaos of the past. We can see de Certeau’s hypotheses regarding the power of historical narration validated in the memories that JFS offers from Missouri and Nauvoo. Late in his life, he was chiefly concerned with telling these stories to other people. What is true for the individual, namely that memory is an act of construction based on particular need, is also true for communities, which are always in the process of constructing shared or “collective” memory.

Jan Assmann, one of the most influential writers on the role of collective memory in religious communities, points out, “We say that the dead will live on in the memory of others, as if this were some kind of natural prolongation of their life. In reality, though, this is an act of resuscitation performed by the desire of the group not to allow the dead to disappear but, with the aid of memory, to keep them as members of their community and to take them with them into their progressive present.”JFS’s personal narrative came increasingly to bear the weight of an entire people. JFS’s memories of Nauvoo, in particular, led him to be the Church’s chief practitioner of anamnesis, the act of constantly stoking the fires of a group’s collective memory. Anamnesis is especially important when it comes to foundational events. Such a person must occupy a special position within his or her culture, a position of absolute rhetorical authority. As one scholar of his history, religion, and memory puts it, the main function of anamnesis within religious communities is to “recall the foundational events that enabled the chain [of memory] to form, and/or [to] affirm [the group’s] power to persist through whatever vicissitudes have come, and will still come, to threaten it.”

JFS became the last prominent keeper and forger of the chain of Mormon memory whose authority derived from personal experience. He was replaced as the Mormon anamnesis, not coincidentally, by his son, Joseph F. Smith Jr., who became Church historian and who crafted collective Mormon historical memory for more than half a century. He drew his authority not from personal experience but rather from his privileged access to documents, his position as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, and his blood relation to the Smith family. This is one of the ways in which JFS’s role as memory-maker rippled far beyond the span of his own life. The memory of Nauvoo eventually became JFS’s to keep for the Church.

Quite apart from his role of performing anamnesis for the Church, JFS was a master myth-maker in his own life. Note here that “myth” does not suggest lying or deliberate falsehood. In this context, myth might best be thought of as “ideology in narrative form.” Myth “naturalizes and legitimizes” ideologies.When applied to the narration of historical events, mythology provides a sense of moral meaning to events in the past that lack such a structure and it convinces the audience that the moral meaning is inevitable and natural. Mythology is an act of narration in which the emplotment of the narrative is driven by a particular, explicit, ideological engine. For JFS, the fuel for the engine was the inexhaustible trauma that flowed from his father’s murder in 1844 and his mother’s death in 1852.

Memorial Sacroscapes: Missouri

Although JFS was only an infant when he left Missouri, the shadow of the events that transpired there follows him into adulthood. In order to understand why Missouri and, later, Nauvoo came to figure so prominently in JFS’s life, especially as he grew older, we may look to a theory of religion developed by Thomas Tweed. Tweed argues, “Whatever else religions do, they move across time and space. They are not static. And they have effects. They leave traces. They leave trails. Sometimes those trails are worth celebrating. . . . Sometimes trails are sites for mourning.”Tweed calls the trails left behind by the movement—both figurative and literal—of a religious movement “sacroscapes.”Sacroscapes help religions make sense of the changes that they make, especially those that are involuntary. Western religions, in particular, hold tightly to the concept of an unchanging God and an accessible Truth. Changes, either in terms of ritual, doctrine, or status, pose potential problems. Successful religions, meaning those that are historically persistent, find ways to make necessary changes so as to remain viable within a given cultural and historical context while simultaneously explaining away the changes as nonexistent, unimportant, or as epiphenomena that are changes in appearance only and which are actually in service of a larger, unchanging phenomenon. This dyadic system of constant change and adjustment in response to historical contingency on one hand and an internal rhetoric of constant stasis on the other is particularly apparent in nineteenth-century Mormonism. Few religions in his history have moved, in Tweed’s multivalent use of that term, so much in so short a time. The nineteenth-century Mormon sacroscape includes various moves from one type of family system to another and back again, from one type of conception of God to a much more radical one, from a centrally-based Zionic ideal to a more diffuse one, and so on. Physically, Mormons moved from New York to Ohio to Missouri to Illinois. But Mormons also moved from Europe and the Pacific to the United States. All of this and more comprise the sacroscape. JFS’s stories about his life became the lens through which later generations of Mormons would wander the trails of joy and, more often, the trauma and tragedy of this shared sacroscape. It was in that capacity that JFS left his accounts of Missouri and Nauvoo, and those accounts can only be understood and analyzed with the notion of the sacroscape in mind.

JFS opened the brief autobiographical essay about his early years in blunt fashion: “November 13th 1838. This is the date of my birth. I was born in Far West, Caldwell Co. Missouri, 13 days after my Father was taken a prisoner by the mob.”JFS’s story starts in the crucible of persecution at the hands of the mobs in Missouri. Missouri found a lasting and active place not only in Mormon memory but also in the Mormon view of the future. Despite the humiliating string of defeats and evictions that stretched the length of the 1830s and despite the ignominious imprisonment of their leader and prophet, Mormons never let Missouri go. There are two basic, related, reasons for this. The first is that the early revelations established that God wanted Independence as his city, where Christ would one day return and rule personally on the earth. The language in those revelations was so specific and so forceful that they simply could not be ignored no matter how grim the actual situation was. Second, a revelation produced by Joseph Smith in 1834, after the Mormons had been driven off their lands in Jackson County, would be given increasing weight as the years moved on. That 1834 revelation spoke of the “redemption of Zion” and said that Zion could be redeemed—that is, Mormon lands reclaimed—“by power.” According to the revelation, “the blessing which I have promised after your tribulations, and the tribulations of your brethren [is] their restoration to the land of Zion, to be established no more to be thrown down.”This promise of a redemption of Zion and a return to Missouri was kept vividly alive throughout the nineteenth century. Many individuals were promised as part of their patriarchal blessings that they would live to return to Missouri in preparation for the second coming of Christ. This belief spread widely and deeply throughout the Mormon culture region.

JFS’s brief sojourn in Missouri had a much greater impact on him and on Mormonism in general than the length of his time there would suggest. In fact, JFS incorporated memorial narratives of the period into his own reminiscences. Memory is a major theme in JFS’s life. One might imagine JFS’s life as existing on two separate tracks. On one track, we find the things he lives “through.” On the other track, we find the things he lives “with.” While everyone has both of these operating in their lives, for JFS, the things that he lived “with” loomed unusually large in his consciousness. The traumatic first ten years of his life remained with him almost constantly until his death. He used these memories to filter, order, arrange, and narrate his lived experiences. The first ten years were the index by which he made sense of the other things that he lived “through.”

Because memory, the body of things JFS lived “with,” is such an important theme in JFS’s life, it is salutary to flesh out what we mean by that term. In recent decades, a major shift has occurred in the way in which scientists understand the nature of memory. Memory used to be imagined as a sort of mental filing system. In this static model, sensory data were thought to be recorded by the brain and then stored away. These stored files could then be accessed when the need arose or when something triggered a memory. The important thing about this model is that it assumed that memories, once formed, remained basically stable. The only possible changes were thought to come from aging or some disease or injury to the structures of the brain responsible for storage.

Today, neurological research has yielded a new understanding of what memory is and how it functions. Memories are not really retrieved as much as they are “reconstructed” each time they are accessed. This reconstruction involves complex interactions among various structures throughout the brain. The memories, thus, are constructed not only out of recorded sensorial data but also out of things that have occurred since the original memory was created. Memory is a dynamic process, and remembering is defined as “the process of activating memory functions” rather than simply an act of retrieval. If this model is correct, then, according to one expert, “it is plausible to say that [memory] does not represent but rather constructs reality.”

This has at least two important implications for our study of JFS. First, we must see his memories, particularly the early ones that he invoked most frequently, as dynamic entities influenced not only by the things through which he lived but also by things that he heard about the past from other people. Memory is a living thing, and JFS’s memories took shape according to how he understood himself and the nature of the world around him. The tone, characters, incidents, and narrative structure of his reminiscences help us understand the factors that shaped his memories. Second, the frequent reconstruction of the memories sometimes led him to include in his own memories things that he could not have actually experienced. One incident in particular took root in JFS’s imagination. Don Carlos Smith, JFS’s uncle, was away from home on a mission for the Church in Tennessee when his wife, Agnes Moulton Coolbrith, was turned out of her home as part of the actions in the Mormon War. I have collected two separate sermons in which JFS recounts this story. Exploring these sermons provides a window into JFS’s worldview and establishes that his sense of self may be traced unambiguously back to the Missouri period despite having been too young to have experienced the events himself. As soon as he had made explicit his personal link to Joseph Smith, JFS began to tell a story about Missouri. He acknowledged that the story he was about to recount occurred “in my babyhood” but suggested that it had never “been recorded at all, and perhaps no one has given utterance to it.” He continued,

My own aunt, who was the wife of Don Carlos Smith and who was then living in exile, having been driven out of her own home, a little log cabin, the best they possessed then, with three little children, a babe in her arms and another little tot holding her hand and another a little older hanging to her skirts, at midnight in the month of November, with the frost in the air and the earth frozen solid, without time to put on her clothes; and she left prints of her feet in blood upon the frozen soil of Missouri. She fled from what she had . . . by the light of the flames that destroyed her little cabin home.

The intricate detail of this story is stunning and the imagery vivid. There is no question that JFS had imagined this event many times over the decades until it came to represent, for him, the entire Mormon experience in Missouri. He carried what was, in effect, a memory that he had appropriated and woven into his own personal story, a memory that captured what Missouri meant to him: homeless, wounded innocents, alone at midnight, standing on ground so cold that not even the blood of a helpless mother could thaw it. This particular anecdote found its way into multiple sermons.

In addition to the December 1915 sermon, he also recited the story on July 22, 1917, at the Liberty Stake conference in Salt Lake City. That gathering had as its main focus the celebration of “Pioneer Day,” which marked the anniversary of the arrival of the first Mormon pioneers into Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847. By the time JFS took to the pulpit in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square that day, he had already heard sermons by several local Church leaders that had focused on the persecutions that led the saints to Utah. “I certainly hope,” JFS began, that “I might be able in the first place to calm my feelings a little, or I fear I shall make a failure of an attempt to talk to you very much.” The remarks made by the previous speakers about the suffering of the Mormons in Missouri, he remarked, “have struck very close to my feelings.” In an effort to calm himself, JFS told the audience that it was not his intention to dwell upon “the hardships caused by the persecutions” of the Mormons. Despite that caveat, he seemed unable to resist. In fact, Smith devoted the lion’s share of his lengthy address to recounting the wrongs done to the Mormons. It was in this context that JFS again told the story of his aunt. Before telling the story, JFS tried again to stop himself, telling his listeners that “I will try to get away from this subject and do not care to dwell on it.” But in the very next sentence, he dove headlong into the horrors of Missouri. As in 1915, he told again of the woman and her children “driven out of their home to escape mob violence in the month of November, when the snow and frost were upon the ground, and with her two little girls, little children” she was cast out into the “wilderness” leaving “the marks of her bloody feet upon the ground.” By this point, JFS was in danger of being overcome by the power of his own words. “It is always dangerous for me to think of those things. I ought not to do it because of the effect upon my feelings; it stirs up the old Adam in me, and I should always pass it up.”

There are three important things that the telling of these stories reveals about JFS. First, there was clearly tension in JFS’s mind about how those memories and feelings fit into the Mormonism of the early twentieth century. He even prefaced his December 1915 remarks about persecution by acknowledging that there was a general sense that such public rehearsals could harm relations with “gentiles” who no longer sought to harm Mormons and who may take offense at being implicated in the gruesome acts of their forbears. Speaking specifically of the stories of the misfortunes in Missouri, JFS said, “That is history which has not been said very much about, because we say now, ‘Hush; don’t wound the feelings and sensibilities of the children of those who drove you out of Missouri. They repent of it, they are sorry for it, they wish you would come back. Now, keep these things silent, don’t say anything about it,’ but you will pardon me for saying it, wont [sic] you.”JFS believed that the memories of the Missouri persecutions were being suppressed by Mormons who wanted to appear polite and wanted to avoid rocking the boat.

Second, and more importantly, these stories leave no doubt that JFS remembered Missouri. He remembered it in the sense that the events there had taken on personal, deeply emotional, psychologically foundational meaning for him. He remembered it as a frozen hellscape devoid of comfort, composed of ice and fire and sheer, brutal indifference. It became for him a prototype of the larger world. It is easy to assume that JFS’s conscious, memory-forming life began in Nauvoo, and this is technically true. But memory is a complex thing, and it is far more than a recording device for our experiences. We recreate memories constantly, and it is clear that JFS presented this story from Missouri in the form of a personal memory. He never attributed the story to anyone. He did not introduce it as a family story or a legend handed down to him. He did not do those things because that is not how he thought about the story. He had, over the years, appropriated the memory and imbibed the experience so deeply that in 1917 he could still get visibly angry over the event. Scholars of trauma and collective memory describe a phenomenon called “vicarious traumatization” in which individuals can actually be traumatized—that is, impacted by physical or emotional events in such a way that the person’s psychological well-being is permanently damaged—by events that are either fictional or real ones in which they did not personally participate.JFS’s memory of the eviction of his aunt seems like a vivid example of vicarious traumatization.

Finally, like everything else JFS ever did, he formed his memory of Missouri in the shadow of the memory of his father. There is no mystery about where JFS might have learned about the eviction of his aunt and cousins. One need look no further than Hyrum Smith’s affidavit that was sworn out in 1843 as part of the attempt of the Mormons to seek financial redress for the property and lives lost in Missouri. Among the many depredations that Hyrum Smith recounted in his affidavit, one finds the story of “the wife of my brother, the late Don Carlos Smith,” who was driven from her home “about 11 o’clock at night, bringing her children along with her, one about two and a half years old, the other a babe in arms. She came on foot, a distance of three miles” being forced to cross a river that was waist deep and trudging “through snow three inches deep.” The “ruffians,” Hyrum concluded, had “burnt up her house.”

The story was important enough to Hyrum Smith to include it in his redress affidavit. JFS would certainly have seen the affidavit if for no other reason than it was published as part of the History of the Church that was produced after the Mormons had arrived in Utah. JFS clearly altered some of the details. Hyrum spoke of two children, JFS of three. JFS mentions nothing of a river and Hyrum says nothing about bloody footprints. Nevertheless, the basic structure of the story is there. JFS’s version is more dramatic, even darkly poetic. His memory of this story was shaped and reshaped over the decades, polished by further horrors and traumas until it became, in JFS’s mind, an exquisitely sharp tool with which he could render for himself and anyone who cared to listen a portrait of the Mormon experience in the nineteenth century.

It is significant that he chose for this a memory that was important to his father. JFS kept the memory of his father ever close at hand. He could hardly have done otherwise even if he had wanted to, especially given the propensity of others to seek him out and talk about his link to the great heroes of Mormon history. In this case, it seems as though JFS may have literally appropriated one of his father’s memories and made of it an anchor for the narrative of persecution, oppression, and martyrdom that would form the core of his identity. JFS and nineteenth-century Mormons in general were tapping into a rich vein of ancient persecution narrative that had been deployed successfully by Christians for many centuries. In 1843, Hyrum Smith spoke to an audience in Nauvoo on the subject, outlining the importance of persecution to the Latter-day Saints. “Persecution,” he taught, “is one of the means of salvation [because] when persecutions cease, we are likely to forget the first commandment.”JFS, in turn, transmitted this trait to his own children. In 1944, decades after JFS’s death, his son Joseph Fielding Smith Jr., wrote to one of his sons, Lewis, “No man in recent times had to endure more hatered [sic] more false accusations and bitterness on the part of the ungodly than did” JFS.A year later, he wrote to another son, Douglas, “Your grandfather spent his life in tribulation. No man was ever abused, vilified, lied about more than was he.”This deep sense of persecution stained JFS’s memorial narratives of his life in Nauvoo just as deeply as those of Missouri.

Memorial Sacroscapes: Nauvoo

As in the case of Missouri, JFS’s childhood in Nauvoo is accessible in two ways: through a recreation of the general historical context and from his own later reminiscences. The former relies on the historical record, and JFS makes few appearances there during the Nauvoo period. We do know a few things, however. JFS’s membership in one of the most important families in Nauvoo would have granted him an elevated status relative to other children his age. He loved to walk the streets of the city, where his father sometimes took him. JFS and his siblings spent time with their grandmother, Lucy Mack Smith, at her home in Nauvoo. They were most amused by Lucy’s practice of sending her dog to the store. Carrying on his back a basket and a grocery list, the dog would in due course return with a basket full of the things Lucy needed.Most of the time, however, JFS could be found at his family’s farm. He loved playing in the barn on the property and in later years would recall with great fondness both barn and farm.

JFS also attended school, at least part of the time. Joseph Smith III recalled that he attended a school starting in 1841 “in a little brick store on the south side of Water Street” with “Hyrum’s children.”The teacher carried a penknife with him at all times, an instrument that he used to rap upon the heads of the children when they were in need of some attention. Although Joseph Smith III does not mention JFS by name, he does indicate that “among Uncle Hyrum’s children who came to this school was a small one whose mother used to call at some time in the afternoon to bring him a cup of milk which he would go outside to drink.”It is strange that JS III did not name this child in his account. JFS would have been three or four and his next older brother, Hyrum Jr., who died in 1841 was mentioned by JS III in the very next sentence. Older than Hyrum, Jr. was John Smith, who, having been born in 1832, was the same age as JS III and thus unlikely to have been described as relatively small. It is likely that the little milk-drinking Smith was JFS himself. Unfortunately, JFS leaves barely any reliable archival trace of his presence in Nauvoo.

One can, however, approach JFS’s Nauvoo years through another, more slippery path: his own impressions and memories. It is not giving away anything to note that Hyrum Smith was murdered in the summer of 1844 and that JFS’s entire life from that point forward was an extended attempt to come to grips with that trauma. JFS’s memories of Nauvoo are historically suspect because he had to look back through the bloody mist of Carthage to access them; they are much more useful in helping us understand his own worldview than they are in helping us understand Nauvoo history.

JFS’s impressions of Nauvoo were remarkably conflicted. In an essay he published in the Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine in 1915 about his childhood, JFS described Nauvoo as both “beautiful” and “dismal.”He recounted the majesty of the temple but pointed out that no one could afford to buy corn. These impressions formed a braided rope of feeling that represented the conflict JFS felt about Nauvoo. On one hand, it was the birthplace of the Mormonism that he defended his entire life. On the other hand, it was the scene of his greatest traumas. One senses that his memories from those years seem far too clear, too crisp and sharp to be the genuine memories imprinted on a three- or four-year-old mind.The memories themselves are worth considering in detail, however, because they tell us something about what Nauvoo came to mean to JFS as he matured. Two memories seem to have been of particular importance to JFS.

Unsurprisingly, all of the memories JFS recounted from the Nauvoo period always include his father. One story that he told multiple times, was of a day on which Joseph and Hyrum came to Hyrum’s house.

Again, while I was a little boy, one day, I think it was just about the noon hour, we were anticipating, or my mother was anticipating the return of my father from somewhere for he and Joseph the prophet had been in concealment away from the mob, and I was looking for them. I went out on the bank of the river, close to the old printing office. I sat on the bank of the river, and presently I saw a skiff starting out from the other side of the river. The river there is a mile wide. They rowed on across the stream until they landed close to where I stood. Out of that little skiff the Prophet and my father alighted and walked up the hill. I joined the hand of my father and we went home to my mother, to my father’s home. Then both went into the house and sat down; they chatted and talked with each other and while my father was changing his clothes—I suppose his collar and cuffs and something of that kind, probably—Joseph the prophet sat there. He took me on his knee and trotted me a little and then he looked at me a little more carefully and finally he said, “Hyrum, what is the matter with Joseph here?” “Well,” he says, “I don’t know; what do you think is the matter?” “Why, he looks as though he had not a drop of blood in him.” “Oh!” Father says, “that is because he has been living on milk only,” for up to that time . . . I had never eaten a thing harder than milk; I was living on it. I do not know whether that had the effect of making me white or pale, but that was the condition that I was in, and that was the remark the Prophet made. I never forgot it.

The detail of this story is impressive. Smith sets the stage so well. His audience would have heard stories of Nauvoo, and the imagery Smith conjures up takes them with him back to the banks of that river, “a mile wide.” The image of the child’s hand in his father’s is poignant. The audience knows the tragedy of that gesture: that Smith’s tiny hand will reach forever after to the hand of his father—a hand that he could never find again. The fine-grained description of Hyrum’s pedestrian actions—changing cuffs and collars—is mesmeric in its humanizing effect. Joseph’s role in this story is intriguing. He is a shadow figure at first, outside of the intimacy of “my father’s home.” He takes young Joseph and bounces him, but the prophet only speaks in the service of the pathos that JFS is crafting for his audience: the pale little boy with nothing but milk to nourish him, foreshadowing the storm that the audience knows is rushing inexorably toward this little boy—a storm that will take first father, then home, then mother. Throughout his life, JFS frequently employed blood as a centrally important motif. It emerged in his memorial narrative of Missouri in the form of bloody footprints, and it manifests in this account— “not a drop of blood in him”—as a statement of JFS’s apparent lack of vitality. Perhaps it was important for JFS to convey to his audience the contrast between his near-invisibility as a boy and his vivaciousness as an old man.

The second memory that we will examine is almost certainly more fiction than fact.

One day during cold weather, my father took me by my hand and led me down the road to a little brick building. It was not much larger than . . . a little beehive, but it was the best they had at that time, and in it was a little sheet-iron stove. I remember the looks of it just as well as if I had seen it yesterday. There I remember the Prophet Joseph, my father, Brigham Young, Sidney Rigdon and Willard Richards and there were a number of others. . . . They met in that hovel to consider what they should do with the obligations that rested in their hands, from those that had been despoiled of all they possessed in the world.

Many Mormons owed money to the Church and to Church leaders but were now incapable of repaying the debts because of the devastated conditions after the exodus from Missouri. JFS recalled that as they sat there with the actual debtors’ contracts in the room, Joseph Smith “opened the door of the stove and stuck them in, and I saw them burn.”If such a meeting took place, it most certainly would have occurred before April 1842, at which time Joseph Smith declared bankruptcy. That would mean that JFS could have been no older than three and a half. I have no doubt that JFS believed sincerely that he remembered this event. The fact is, however, that this would have been nearly impossible. So we have in this case a memory that he created from some unknown sources and that reflects his sense of what Nauvoo was all about. The memory, however, contains elements of the grand narrative that JFS believed undergirded his entire life. It paints the Mormons as victims who refused to claim victimhood. By destroying the notes and forgiving the debts, Joseph Smith was, in a sense, refusing to further the aims of the “mobs” through self-sacrifice. By the time JFS told this story, the Smith brothers had long since been enshrined as the martyrs of Mormonism from whose blood the seed of the Church sprang. It is not surprising, then, that JFS fashioned a memory that carried echoes of the self-sacrificial martyrdom theme.

Conclusion

This brief essay represents an effort to examine JFS’s worldview by applying theoretical templates from memory studies to the historical data dealing with his life. Although space allows for close reading of only a few pieces of data, these are sufficient to suggest that remembering and creating memory affected JFS and the Church as a whole in complex and fascinating ways. His early traumas shaped his overall sense of his own past and, by virtue of his position as a living link to Joseph Smith, the past of Mormonism at large. Memory becomes increasingly important to everyone as they age, but JFS’s memory was appropriated by Mormons who longed to touch the experiences of the earliest days and who needed to be close, both physically and memorially, to the blood of “the martyrs.” This appropriation placed great pressure on JFS to perform, as memory, the history of persecution and martyrdom that had come to define the Mormon experience in the nineteenth century.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue