Articles/Essays – Volume 03, No. 2

The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri: Translations and Interpretations: Phase One

The investigation of the Book of Abraham has still far to go before we can start drawing significant conclusions. Even the first preliminary stage of the operation is by no means completed, for we still have to determine exactly what the relationship was supposed to be between the official text and the Egyptian papyri in the possession of Joseph Smith, and how Smith treated the papyri. The problem of Joseph Smith as an inspired prophet never enters into the discussion at all, since that lies entirely beyond the province of scholarship: the experts must judge him as a translator or not at all. But translator of what? While he freely circulated reproductions of the three Facsimiles with his interpretation of them, inviting comment from one and all, he never specified from what particular papyri he was translating the text proper or by what process.

Unlike the Book of Mormon, the Pearl of Great Price is a work in progress, a selection made after the Prophet’s death of writings that do not make up a single connected or completed work. There are two known manuscripts of the Book of Abraham and there may be yet other undiscovered. One of them, a study of visible symbols, is not the sort of thing that anyone would dictate to another, everything being addressed to the eye; but is it in the handwriting of Joseph Smith? It is certainly not his spelling. There is a lot we would like to know about these strange texts. There are signs of experimenting here, and the writer feels free to make alterations as he goes. We must not forget that Joseph Smith was not only permitted but commanded to cast about in his own mind for the answers to things before asking for revelation (DC 9:7–8), just as the Nephites were commanded to “ponder upon the things” they wished to understand and so to “prepare your minds” for revelation (3 Ne. 17:3), and as the Brother of Jared, when he asked the Lord how he should light his ships was told to solve the problem for himself as best he might before appealing for supernatural aid (Ether 3–4). If we do not have an official Urtext of the Pearl of Great Price we do have some manuscripts which indicate independent thinking and speculation.

Under this heading we would certainly place the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar, which is no more fantastic than the Egyptological gymnastics of such a great thinker as Leibniz—there seems to be something about Egyptian which brings out the latent crack-pot in many of us. The Alphabet and Grammar consists of two quite different documents. One is the list of signs, each accompanied by a short phonetic rendering and a brief interpretation; here there is nothing extraordinary about the length of each “translation,” whatever one might think of its content. But it is a wholly different story when we come to the second document, where one brief symbol may be followed not by a corresponding transliteration and translation but by a whole page or more of history or commentary. Either we have here a totally different language from that in the sign-lists, which show a quite rational sense of proportion between Egyptian symbols and English sentences, or else this is a “translation” in an entirely different sense.

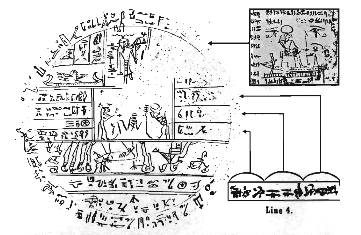

If the few symbols here given, which are taken from the brief Sen-Sen fragment, are the Egyptian source of the Book of Abraham, why were they never given out as such to the public? Because it was Smith’s secret source of information? It could not have been that unless he was actually translating it. At best the symbols on the left would seem to indicate section-headings. To see in them the whole book of Abraham is to fly in the face of reason and attribute our insanity to Joseph Smith. Any thought of a literal translation is of course out of the question, but to identify the symbols in the Sen-Sen papyrus with the text of the entire book of Abraham we must assume that the sly Joseph Smith and his competent co-workers remained blissfully unaware of a discrepancy so gross that a cretin could not miss it. In the absence of any explanation by its writer, the very arrangement of the texts, while indicating a definite connection, whatever it might be, between the symbols and the English text, strikes one forcefully at first glance as a clear indication that the person who wrote it could not possibly have intended the one text to pass as a translation of the other, especially since he has already demonstrated a sane sense of proportion in the preceding sign-lists.

Those who insist that “the Egyptian characters cannot conceivably have enough information . . . to convey the amount of material translated from them,” are the very parties who do conceive of just that, and insist that Joseph Smith actually did derive all that stuff from them. They can’t have it both ways. If nobody could possibly get the Book of Abraham out of the Sen-Sen papyrus, then we can be quite sure that nobody did—nobody including Joseph Smith. But in that case what is the charge against him—that he pretended to be translating the Sen-Sen papyrus? Then why did he keep it a secret? Since the Sen-Sen business makes very little sense to anybody, while the Book of Abraham makes very good sense, one might suppose that Smith could have produced the latter without any reference to the former—that he could have written the Book of Abraham more easily, in fact, without having to bother himself with those meaningless squiggles. But if the Sen-Sen symbols are expendable, why does he use them at all? His only purpose would have been to impress others, but he keeps the whole operation strictly to himself and never circulates the Sen-Sen papyrus as he did the Facsimiles. And why on earth would he fasten on this particularly ugly little piece and completely bypass the whole collection of handsome illustrated· documents at his disposal? Did he really think he was translating? If so he was acting in good faith. But was he really translating? If so, it was by a process which quite escapes the understanding of the specialists and lies in the realm of the imponderable.

No one has begun to look into the Sen-Sen problem seriously. In the signlists, for example, there are many corrections and alterations in the English translation and the handwriting is interrupted and hesitant. But in the text that accompanies the Sen-Sen signs there are no deletions, additions or corrections, the spelling is perfect, and the handwriting is flowing and unfaltering. The English text then is plainly not being composed for the first time in this manuscript, which is being copied from an already complete English text. Is somebody trying to match up the already available text with the Sen-Sen symbols? Whatever is happening, the finished and almost flawless manuscript is not being derived from the symbols placed to the left of it. The connection between the two remains a mystery.

Today nobody claims that Joseph Smith got his information through ordinary scholarly channels. In that case one wonders how any amount of checking along ordinary scholarly channels is going to get us very far. But that does not excuse us from going as far as we can. Many questions are still to be answered concerning the whole bulk of the Egyptian manuscripts possessed by Joseph Smith. Were important parts missing in 1830? Was the jumbling and cutting done “before it was brought to Kirtland?” Who pasted the things together? Who cut them up? We are told that the papyri were in beautiful condition when Joseph Smith got them, and that one of them when unrolled on the floor extended through two rooms of the Mansion House. Those we have today are mounted on paper showing maps of the Kirtland area, but that suggests that the mounting took place only after the Kirtland period, when all thought of returning to Kirtland was given up and the precious maps had become waste-paper. Such questions are interesting and relevant, but for the study of the Book of Abraham their interest is only secondary since none of the Book of the Dead papyri were consulted in the composing of that book, any more than the Arabic Mss were.

When I first saw photos of the papyri I made myself disagreeable by throwing a great deal of cold water around. For publicity they were great, and as far as I can see their main value is still in calling the attention of Latter-day Saints to the existence of scriptures which they have studiously ignored through the years. But after all, what do the papyri tell us? That Joseph Smith had them, that he studied them, and that the smallest and most insignificant-looking of them is connected in some mysterious way to the Pearl of Great Price. There is really very little new here to shed light on the Book of Abraham. We must look elsewhere for further light and knowledge. For after all, the Book of Abraham does have something to say, and that should be the point of departure in any serious investigation of its authenticity. Here we have an instructive parallel with the Book of Mormon.

There is nothing in the circumstances surrounding the production of the Book of Mormon to give one the least confidence in the authenticity of the book. But what a book! Without the book anyone would be justified in labelling the whole story of its coming forth as utterly fantastic and impossible. But having the book changes everything. Critics have claimed to find all sorts of things wrong with it, but we can allow for such things since 1) our own ignorance is a very real quantity, and 2) the Book of Mormon itself makes due allowance for “the mistakes of men” in its production. The real problem is not to account for the times the Book of Mormon is or seems to be mistaken, but for the times it is right. Within the past year, for example, we have discovered and published a brief and all too inadequate resumé of a military section of the Book of Mormon which displays an absolutely staggering knowledge of strategy and tactics. Well, this sort of thing has to be accounted for, and it is only by going from the known to the unknown that we can eventually test those things which in our present ignorance seem utterly absurd but make perfectly good sense once we know what is going on.

So it is also with the Pearl of Great Price. We are completely in the dark as to how it was produced, but we are anything but helpless with the wealth of detailed material it offers us to test it by. The strange history, the strange rites, the strange doctrines all meet us again and again in ancient sources far removed from Egypt but all connected with the name of Abraham. The great mass of Abraham legends preserved in Jewish, Moslem, Christian, and even Classical sources are known to few Egyptologists, but as we read through them we find Egypt coming into the picture again and again in new and strange relationships. True, the soil of Egypt has given us absolutely nothing on the subject of Abraham in Egypt, but for that matter S. Herrmann is now maintaining that there is not the slightest scrap of evidence that Israel itself was ever in Egypt. No Egyptian evidence, perhaps, but then Egyptian sources are not the only sources, and it is folly to come out with a verdict about the Book of Abraham until we have studied fully and carefully the great and growing corpus of ancient Abrahamic literature, even if it takes us years to get through it.

For after all, the Book of Abraham itself is a book of legends about Abraham which can only be tested in the light of other such legends, which can at least give us hints as to whether Joseph Smith was making it all up or not. And here we can announce in advance that the evidence that Smith’s stories are not original is quite overwhelming. This of course raises the question whether Joseph Smith could have had access to any of our non-biblical sources, and if so to which and how. Those are things that need looking into, though it is only fair to point out that if those scholars of the 20th century who have unanimously condemned Joseph Smith for his total ignorance of all things ancient and oriental, themselves know nothing about these things, the chances that Smith could have known anything at all about them are, to say the least, not brilliant. The one scholar who did know something about those other sources was, as might be expected, the omniscient Budge, and he more than hinted that Joseph Smith was bringing such sources under contribution. Was then the youthful rustic from upstate New York another Budge?

Now the Abraham literature is of course a great hodge-podge of stuff coming from many different sources and many different centuries. But because of the ways in which legends and traditions were swapped around anciently, with very ancient and authentic bits sometimes turning up in the most unlikely places, often buried in bushels of nonsense, we cannot escape the obligation of reading everything. In the process one is constantly coming upon odd and disconnected details that bring one up with a start, and it is these that provide the great interest and challenge in the game. Take the Sen-Sen papyrus itself, for instance. Messrs Heward and Tanner raise three objections to it while completely overlooking their significance. The first is the comical disproportion between the Egyptian symbols and the English text which they suppose to be derived from them. They have left the phenomenon completely unexplained. The second is that the papyrus is too late to belong to Abraham, but we have already shown that the expression “by his own Hand” was understood to mean that Abraham and no other wrote the book, and cannot serve as a criterion for dating the papyrus (Era 71, 20f); incidentally, there is no question in ancient history more perplexing and fascinating than that of the chronology of Abraham. But the main point the critics wish to make is that, “most important, the Egyptian has been translated, and it has no recognizable connection with the subject matter of the Book of Abraham.” With what subject matter does it have recognizable connection, bearing in mind that “ . . . the underlying mythology [as T. G. Allen writes of far less mysterious texts] must be largely inferred”? (e.g. B.D., p. 6.). Even the casual reader can see that there is cosmological matter here, with the owner of the papyrus longing to shine in the heavens as some sort of physical entity along with the sun, moon and Orion; also he places great importance on his patriarchal lineage and wants to be pure, nay baptized, so as to enter a higher kingdom, to achieve, in fact, resurrection and eternal life. And these teachings and expressions are secret, to be kept scrupulously out of the hands of the uninitiated. And all these things have nothing to do with the subject matter of the Pearl of Great Price? What else, then?

And here, right in the Sen-Sen papyrus we come upon one of these odd and disconnected details we just talked about. For we find here a quite typical identification of some person “born of Tayhebty” with Osiris, Horus, and a Stone of Righteousness, whatever that is—“Stone of Righteousness is your name.” Now in the Mormon scriptures we have the same sort of puzzling identities: Abraham, according to the Book of Abraham (3:1) possessed the mysterious Urim and Thummin (I ask myself if these can represent Wr and Tm of Heliopolis, where there were two important stones—but let it pass, things are confusing enough as it is); by these stones the Lord spoke to Abraham (why is the ideogram for the Great Seer of On written with two stones?) and showed him the starry heavens (vv. 2, 4—don’t tell me we have here the field-lens and ocular of a telescope). In Alma 37:23 Urim and Thummin is called “a stone” the function of which is to distinguish the righteous from the wicked (“Stone of Righteousness”?—oops, sorry!), and the person who possesses it goes by the code-name of Gazelem; so that in the D.C. 78:9, Gazelem is said to be Enoch, though here identified with Joseph Smith. In some of our old “Abraham” literature Enoch, usually as Idrisi, is identified with both Abraham and Osiris. It is so easy to make and establish such identifications, one might think, that they can have no great significance. But that is just what remains to be seen—let’s not get ahead of the game, or overlook any possibility that there might be something there after all—“If it looks like an elephant,” Professor Popper used to say, “call it an elephant!”

Or take another case, equally odd. In Spell 31 of the Book of the Dead in that same MS (R) in which Professor Wilson detects the closest resemblances to the Joseph Smith Book of the Dead papyrus, occurs the statement, “I am truly Osiris, to whom his Father Geb and his Mother Nut were sealed . . .” To this Professor Allen appends a footnote, advising the reader to “Cf. Mormon rite of sealing children to parents.” Why do that if there can be no possible connection between them? It so happens that there are extensive passages in the Coffin Texts (from Spell 131 on) in which the sealing of one’s family to one in the next world is treated in exactly the same sense and the same terms as those familiar to Mormons but utterly foreign to outsiders. A coincidence, to be sure, but there are altogether too many such coincidences. No non-Mormon can be criticized for being ignorant of Mormonism—after all, there is no end to what people have been willing to believe. But if all this to-do is to pass as a critique of Joseph Smith and Mormonism, it is well that the critics know what they are criticizing. And that is just where the whole business breaks down. If the verdict of the learned has failed hitherto to have any telling effect on the prestige of Joseph Smith save on those giddy Mormons who wish to be thought intellectual, it is because the experts have passed judgment on a thing they do not understand; in the most literal sense of the word they do not know what they are talking about, because they do not know what Joseph Smith actually taught.

So far everything that has appeared in print about the newly found papyri has been written either by hysterical opponents of everything Mormon or by people innocent of any bias in favor of Joseph Smith, (our own efforts have until now been confined to the affair of 1912, which many people are still persuaded settled the hash of the Book of Abraham for all time). Which means that we have now heard the worst. And it is surprisingly feeble: We have learned that Joseph Smith experimented—but we already knew that; we have learned that the papyri are of relatively late date—but the Mormons have always known that; we have seen some of the papyri that were in Smith’s possession, but there is no evidence that we have seen them all, and it is apparent that only one small piece among them has any direct bearing on the Book of Abraham—and what the connection is remains a complete mystery. The Egyptologists—and we can be everlastingly grateful that they are among the ablest and most honorable scholars who ever lived—have supplied some interesting footnotes to the text, but these offer poor enough pickings for anyone seeking occasion against the Prophet.

So now it is time to hear the other side of the story, for after all it is just possible that there are things that might be said in favor of the Book of Abraham. So far no one has asked how Smith came to produce a history of Abraham which can be matched at every point from a wealth of ancient sources—Jewish and Christian apocrypha, Talmud, Mishna, even Gnostic, Hasidic, and Cabbalistic writings, Moslem commentators, sectaries of the desert such as Mandaeans and Qumran people, even the church Fathers and Classical writers. Even a casual reading of the Book of Abraham shows that the story refers not so much to unique historic events as to ritual forms and traditions—all these must be checked. So far we have heard what is wrong or at least suspect about the Book of Abraham, but as yet nobody has cared to report on the other side of the picture. It is for that we are saving our footnotes

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue