Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 1

The Early Twentieth Century Temples

When the final capstone of the tallest spire of the Salt Lake Temple was set into place on April 6, 1892, it was a time for celebration as the crowds filling Temple Square and the surrounding streets waved handkerchiefs and shouted hosannas. The occasion was a historic milestone, marking not only the near-completion of the Church’s most ambitious building project but the end of an era as well. The temple had been conceived! more than two generations earlier as a symbol of the pioneers’ Rocky Mountain Kingdom, the spires on the east end representing the spiritual leadership of the Melchizedek Priesthood, and those on the west, the worldly leadership of the Aaronic Priesthood. Standing in the symbolic center of the capital city of the kingdom, it embodied Joseph Smith’s dream of a city of Zion, independent and prosperous, where the economic, political, social and religious life of the community would all be centered on the Church and its leaders. But by 1892, the kingdom had changed. Mormon isolation in the mountains had vanished with improved transportation and the arrival of a large Gentile population. Polygamy had been abandoned, church control of economic and political life had been considerably reduced and Mormons had begun to see themselves as part of the larger American society.

Some of these changes in Mormon life were suggested by changes in parts of the temple building itself. It had been planned in a mixture of styles typical of the 1840s and 1850s but the interiors were designed in the 1880s and 90s in a more opulent Victorian mode. The original plans had called for weathervanes on top of wooden spires like those on colonial churches in New England, but the finished building had stone spires and a gold-leafed statue in a Greek or Roman tunic similar to the allegorical figures on top of many public buildings of the period. Perhaps the temple annex was the most dramatic change of all, designed in a popular Victorian version of the Byzantine style—the traditional style of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Until this time, Mormon architecture had been dominated by a simplified blend of American colonial, Greek Revival and Gothic Revival forms, even as more exotic and elaborate styles had become fashionable elsewhere. But the temple annex showed that the Latter-day Saint entry into the mainstream of American life would include imitation of the larger society’s architecture as well.

Many meetinghouses and tabernacles were built in Latter-day Saint communities around the time of the completion of the Salt Lake Temple and over the next two decades. Like the temple annex, they demonstrated a decline in the popularity of the old styles and a willingness to experiment with new ideas. A Russian onion-shaped dome appeared on the Salt Lake 19th Ward, only a few blocks from Temple Square. The Provo Sixth Ward, now destroyed, combined a curved baroque gable with beehive-shaped pinnacles. Some buildings adopted classical domes and porticoes with varying degrees of success, while others made use of Tudor, Tuscan and Spanish architectural elements.

In some cases, the new generation of architects brought a higher degree of sophistication and stylistic purity to the architecture of the Church. Lehi’s handsome tabernacle demonstrated the familiarity of its European architect with classical forms and details, and the tabernacle in Wellsville showed the same degree of correctness in its use of the Gothic style.

Perhaps the most significant architectural event in Utah in the first years of this century was the 1911 competition for the design of the state capitol. The progress of the local architectural profession was evident in the fact that the designs submitted by nationally prominent architects were not noticeably superior to those of most of the major local firms. The winning design was by Utah resident William Kletting, the European-trained architect of the Lehi Tabernacle. Anthon H. Lund of the First Presidency served on the committee that selected this design.

By the first decade of this century, the Church had achieved a measure of renewed confidence and stability after four decades of governmental harassment and financial difficulties. Joseph F. Smith1 the first second-generation Latter-day Saint to serve as President of the Church, demonstrated this new confidence by directing the construction of a number of new buildings for the headquarters of the Church, including an impressive new Church Administration Building in severe classical style, upright and proper, and solid as a bank. In 1912, when construction of the Administration Building was in progress, the First Presidency decided! to begin yet another important structure, a new temple in southern Alberta, Canada.

Architecturally, the new temple posed a problem. No new temples had been begun since the death of Brigham Young. With the changes in architectural fashion and the new image of the Church, which of all the current styles of architecture would be proper for such an important building? Faced with this question, the First Presidency decided to seek the advice of the most talented men available. Following the lead of the Utah State Capitol Commission of the year before, they invited LDS architects to participate in an anonymous competition for the design of the temple. To prepare instructions for the competition, the First Presidency and Presiding Bishop met at the Manti Temple with a young and relatively unknown architect1 Hyrum Pope. They decided that the new temple would accommodate about the same number of people as the Manti Temple, but that it would be built more economically, without the large assembly room on the top floor, and without expensive but relatively useless towers. Hyrum Pope prepared the competition program, and seven architectural firms, including his own, responded by submitting drawings which were placed on public display before selection was made. Most of the proposals looked to the past for their inspiration; some had towers and pinnacles reminiscent of the Salt Lake Temple.[1] Although none of the losing drawings seem to have survived, a detailed written description of one of them suggests both an elaborate design and an elaborate symbolic scheme which was apparently intended to appeal to the brethren: “The five [pinnacles] on each of the four towers, the three on the main front of the building and the three on the rear [make] twenty-six in all and represent the General Authorities of the Church: Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, Charles W. Penrose, Francis R. Lyman, Heber J. Grant . . . [etc.].”[2] However, the First Presidency passed over these traditional and flattering schemes to choose instead a daringly modem design. When the winning entry was announced on January 1, 1913, it was learned that the winners were Hyrum Pope and Harold Burton, two young architects who had been in business less than three years. Pope, the engineer and business manager of the firm, was a capable and ambitious German immigrant of thirty-two. His inside knowledge as author of the competition program may have given his firm some advantage, in spite of the anonymous nature of the submission process. Burton, the junior partner and designer, was only twenty-five years old, and had not yet been inside a temple. This commission launched their prolific and creative careers as some of the most influential and successful architects in the Church.

The splendid winning design for the temple showed some similarities to the work of the great modem American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. Working in Chicago over the previous two decades, Wright had designed residences and public buildings that were bold in form, original in their geometric decorative details and carefully blended with their natural surroundings. Pope and Burton were among Wright’s earliest admirers in the western United States. There was also a vague resemblance in the temple to the pre-Columbian ruins of Mexico and Central America, which Burton greatly admired.[3] Combining these influences, the temple design was in the forefront of American architecture of the period.

The interior arrangement was equally satisfying. Without a large assembly room on the upper floor, there was more freedom to experiment with a new design. Burton had a difficult and frustrating time with this part of the design until a very simple and logical floor plan occurred to him. The four ordinance rooms would be placed around the center of the building like the spokes of a wheel, each room extending toward one of the cardinal directions. Smaller diagonal projections between the main rooms would contain stairways and minor rooms. The celestial room would be placed in the center at the very top of the building, with the baptistry directly below. As a person moved through the ordinance rooms, he would follow a circular path through each of the four wings, finally passing into the center in the celestial room. Each room was a few steps higher than the one before, with the celestial room and the adjacent sealing rooms the highest of all. Thus the architectural arrangement reinforced the idea of progression found in the temple ceremony itself.

The style of the temple was similar to the Salt Lake First Ward, the first building designed by Pope and Burton two years earlier. The influence of Frank Lloyd Wright is evident in a comparison between the First Ward and Wright’s famous Larkin Building in Buffalo, New York. The heavy buttresses framing the windows and the geometric carving near the top of the buttresses are similar on the two buildings.

Entrance to the temple was through a set of handsome gates, made in a pattern similar to some of Wright’s leaded glass windows. The gates opened onto a courtyard, which provided a transition between the inside and outside of the building. To say that the temple was influenced by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright does not imply that it was lacking in originality. Indeed, Pope and Burton’s great achievement was their ability to use the newest and best design ideas in a way that was particularly appropriate for Latter-day Saint worship.

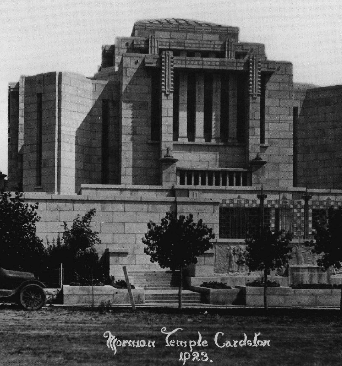

The unity of the exterior and interior, a basic principle of modem architecture, was evident in the fact that the major rooms inside the temple were the most prominent features outside as well. The ordinance rooms formed the major wings of the building, smaller rooms and stairways formed the minor wings between them, and the celestial room projected above them all in the center. The pyramid-shaped silhouette was particularly well-suited to the temple’s location on a low hill in the midst of a broad prairie, since the temple appeared equally strong, well-proportioned and handsome from all angles. The retaining wall around its base created a platform for the building in the vast landscape, and the symmetrical design turned its back on no one. Although completely modem in style, the new temple possessed the same feeling of permanence, solidity and dignity that had characterized the earlier temples. Ground was broken for construction in 1913, but the severity of Canadian winters, the remote location and the interruption of World War I extended the completion time required to a full decade.

During this time, more than twenty chapels and tabernacles were built in a similar style to that of the temple. Two of the finest were designed by other architects: the Parowan Third Ward by Miles Miller and the Ogden Deaf Branch by Leslie Hodgson, both still in use today. Pope and Burton designed a number of meetinghouses in the mission field, including Portland, Oregon, Denver, Colorado and Brooklyn, New York, as well as chapels in Utah. The style became so popular in the Church that one Deseret News writer, evidently unfamiliar with Frank Lloyd Wright, wrote that the work of Pope and Burton “has resulted in the production of what might be termed a strictly ‘Mormon’ style of architecture.”[4] Although the style was not wholly original, these Mormon structures surely constituted one of the most remarkable collections of early modem buildings anywhere.

In 1915, while on a visit to the Hawaiian Islands where he had served as a young missionary, President Joseph F. Smith was inspired to dedicate a temple site at the church plantation at Laie. When he returned to Salt Lake City, he asked Pope and Burton to prepare plans for a smaller version of the Alberta Temple to be built there. However, the architects, recognizing that the hillside site in Hawaii was quite different from the plains of Alberta, suggested a different approach. Although the same basic plan was used, the minor wings which projected diagonally in the Canadian temple were eliminated from the plan in Hawaii, giving the smaller building a simpler, more classical form with a definite front and back. The style of the building was closer to the pre-Columbian architecture of Mexico and Central America than the Canadian temple had been. Burton knew the Mayan temples from engravings by Catherwood, and he borrowed some of the details in the engravings quite literally. Burton also recognized that the tiny building would be dwarfed by its dramatic setting, so he surrounded it with elaborate gardens to give it a monumental presence. The temple thus became the main feature in a symmetrical composition of fountains and pavilions, trees and walkways arranged along an axis connecting the mountains with the sea. Since good building stone was not available locally, the building was constructed of reinforced concrete poured in place, a technique pioneered in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unitarian Unity Temple in Chicago just a decade earlier. Comparison with Wright’s Barnsdall House, built in Los Angeles at about the same time as the Hawaiian Temple, demonstrates how Pope and Burton’s stylistic development paralleled that of Wright.

While in Hawaii, Harold Burton met a twenty-five-year-old missionary, who was helping in the plantation store, named LeConte Stewart. A talented artist, he had studied at the New York Art Students League before coming on his mission. Burton placed him in charge of the interior finishing of the temple and assigned him to paint the murals in the creation and garden rooms. Two older and better known Utah artists, A. B. Wright and L. A. Ramsey, painted murals in the baptistry and the world room. The ordinance rooms were small and simple, with wood mouldings framing the murals in long horizontal bands. Fine light fixtures and furniture were designed by the architects to harmonize with the modem style of the building. J. Leo Fairbanks, a thirty-nine-year-old painter and sculptor, came to Hawaii to do the sculpture work, bringing with him his talented nineteen-year-old brother, Avard, who carved the beautiful baptismal font with its twelve oxen. Together they made the friezes on the top of the building representing teachings from the Old Testament, New Testament, Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants. At the head of the fountains, they made a panel called “Maternity” depicting a Polynesian. mother and child. When the building and gardens were completed and dedicated in 1919, it was one of the finest pieces of religious architecture in the Hawaiian Islands.

Meanwhile, work was also progressing on the Alberta Temple, with some of the same artists taking part. The interiors at Alberta were more elaborate than those in Hawaii. Designed to reinforce and enrich the idea of progression as the theme of the architectural design, each room was richer in color and detail than the one before. The simplest of the ordinance rooms was the creation room, with oak woodwork and paintings by LeConte Stewart. The artist, using a pointillist style with small daubs of color similar to the French Impressionists, created a shimmering effect suggestive of the process of creation. The garden room was panelled in birdseye maple, richer in color and grain than the oak of the previous room, with murals by one of LeConte Stewart’s teachers, Lee Greene Richards. One of Richards’ teachers, Edwin Evans, worked on the murals in the world room with his student Florence Christensen, thus completing the span of three generations of artists at work side by side. This room was panelled in South American walnut, and the terrestrial room which followed had large panels of rich mahogany from Africa and small paintings by A. B. Wright. The climax was reached in the celestial room where a large expanse of mahogany was set above a wainscot of polished Utah onyx on a marble base. The furnishings were designed by the architects and finished in place to match the woodwork of each room. The couches and table in the celestial room also had decorative carvings which matched the details of the woodwork. Together with the stencil painting on the ceiling, the wood inlays, leaded windows, decorative grillworks and drapes, these furnishings created a subtle harmony of colors and textures suggestive of the harmony and peace of the celestial world. Matched wood panelling also ornamented the sealing rooms. The beautiful font, which has been recast in recent years for use in other temples, was the work of Torleif Knaphus, a Norwegian convert to the Church.

In 1920, three years before the Alberta Temple was finished, the First Presidency decided to proceed with the construction of yet another temple, this one in Mesa, Arizona. Heber J. Grant, who had become President of the Church following the death of Joseph F. Smith, decided to initiate another competition for the design of the temple. However, instead of an open public competition, like the one in 1912, he invited three of the leading Salt Lake City architectural firms to submit their ideas: Pope and Burton, Young and Hansen and Cannon and Fetzer. All three sets of drawings are extant today. The Cannon and Fetzer design was distinctly Spanish in flavor, reflecting the great surge in popularity of the Spanish Baroque style in the wake of the Columbian Exposition in San Diego in 1916 where some fine buildings had been done in that style. For their proposal, Pope and Burton kept the same plan they had used in the previous two temples, but they turned away from the Frank Lloyd Wright style toward a more traditional, classical composition with a stepped dome in the center. The winning design was submitted by Don Carlos Young, Jr. and Ramm Hansen. Fortunately, some of their design sketches have been preserved showing the evolution of their design.

Two early sketches show a massive building on a broad foundation story, one with a dome and the other with a pyramidal roof. Another early sketch is similar to the influential Masonic temple of the Scottish Rite in Washington, D.C. by John Russell Pope—a building seen by many contemporaries as the epitome of academic classicism. The resemblance between the two designs shows that Young and Hansen were striving for the same classical grandeur. Their final design was less monumental, more graceful and restrained with a flat roof and elegant classical details. The exterior of the building was sheathed in glazed terra cotta tile, a durable material that was popular at the time. Some of the tiles at the cornice line contained a sculptured frieze showing the gathering of Israel to Zion—Indians, Europeans, Polynesians, and other peoples are represented. The handsome baptismal font, also covered with richly detailed terra cotta tile, was the work of Torleif Knaphus. The arrangement of the interior of the building was a departure from earlier temples, using a central axis as the main organizing device in proper classical tradition. The building was placed on center with the street that it faced. A reflection pool was placed on axis just inside the temple gates, and the main entrance was located in the center of the facade with inscriptions above. A temple patron would enter through this portal and pass through a small vestibule into a wide foyer with another portal on center opposite the entrance. After waiting for the appropriate time in the chapel off the foyer, the patron would pass through this second portal and up a few steps where he could catch a glimpse of the grand stairway ahead. However, before ascending the stairs, men and women would go into dressing rooms at either side to clothe themselves in white. Then they would return again to the base of the stairs and continue their procession upward towards another portal at the top. Before reaching their goal, however, they would tum to the right at a landing and enter the creation room.

The creation room was decorated with fine murals by Norwegian-born Frithjof Weberg. Next, the visitor would proceed through the other ordinance rooms that made a ring around the central stair hall—the garden room with murals by A. B. Wright1 then the world room with appropriate desert scenes by LeConte Stewart, the terrestrial room, and finally into the celestial room, which was appointed like the salon of a fashionable mansion. Finally, the people would emerge from the celestial room through the portal at the top of the stairs that had been their original goal and descend the stairs together. This scheme provided a richly symbolic interpretation of progression, allowing glimpses ahead., but requiring several steps of preparation and instruction before the journey could be completed. Thus Young and Hansen were as successful in using the classical architectural vocabulary of grand stairs and central axes to create a setting for temple worship as Pope and Burton had been before them in using a Wrightian vocabulary for the same purpose.

The history and development of these three magnificent buildings suggest some ideas that may be relevant today as the Church seeks to build new temples around the world. First, the design process included a search for the most talented people in the Church at the time. Competitions allowed new people to demonstrate their abilities, and commissions to work on these buildings provided great assistance to several young artists and architects just starting on their careers. Second, the buildings were adapted to their surroundings: the plains of Alberta; a hillside in Hawaii; the termination of a street in Arizona. In their color, form and landscaping, they fitted gracefully into the countryside around them. Third, they successfully used the best design ideas of their generation to express Latter-day Saint concepts of worship—thus creating buildings th!:lt were both modem and Mormon. Fourth, the collaboration of many devout and skillful people produced structures of remarkably high aesthetic and spiritual value—architecture comparable with the best buildings of their time anywhere. They remain today some of the most precious pieces of our cultural heritage. They should also serve as an inspiration and a challenge for Mormon artists and architects of our generation as they strive to give expression to their faith.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Letter, Harold W. Burton to Randolph W. Linehan, 20 May 1969, Historical Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, MSS.

[2] “Description of Temple to Be Built by the Latter-day Saints at Canada,” Historical Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, MSS, Alberta Temple papers.

[3] Letter (see 1. above)

[4] “New $10,000 L.D.S. Mission Home,” Deseret Evening News, 19 December 1914.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue