Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

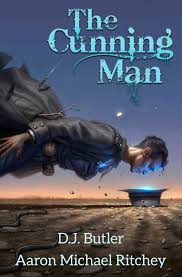

The Cunning Man and Fiction of the Mormon Corridor D. J. Butler and Aaron Michael Ritchey. The Cunning Man

On December 6, 2019, the Western Mining and Railroad Museum in Helper, Utah hosted a release party for The Cunning Man. The novel, which has scenes in the city and in the old coal mines nearby up Spring Canyon, is set during the Great Depression and features a Mormon protagonist, Hiram Woolley, who uses faith-powered folk magic to face down old evil within a new and fast-changing world.

There is a vibrant tradition in Mormon literature of searching for the Mormon Corridor’s soul through tales grounded in its historical centers of economic activity. Levi Peterson’s The Backslider is the great Mormon ranching novel. Darin Cozzens’s Light of the New Day choreographs its meditations on change to the rhythms of farm life. The Cunning Man now joins Carla Kelly’s My Loving Vigil Keeping in turning its attention to the mines dispersed at the geographical and social fringes of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Mormon Corridor life.

I like the mine novels. Both Kelly’s novel and The Cunning Man introduce us to multiethnic communities—“Dey call Helper ‘de town of fifty-seven varieties,’” one miner jokes in The Cunning Man (184)—where the only thing everyone has in common is debt owed to the local company store. In both novels, the dangers of mine life (economic, social, and physical) loom large. And in both, the outsider protagonists feel a certain sense of connection to the mining towns they find themselves in because of their own marginal status in respectable society.

Hiram’s marginal, liminal position comes in part because the respectable world is growing less tolerant of the Christian charms whose use his grandmother trained him in. Though prayers, scripture study, and priesthood blessings are smiled upon in Mormon communities, the use of objects like rods or protective amulets made with just the right passage or invocation inscribed on them is met with a growing unease. “Is this nineteen thirty-five . . . or eighteen thirty-five?” a counselor in the presiding bishopric asks Hiram by way of warning when he’s assigned to deliver food from the storehouse to the Kimball mine (4). The warning is hardly necessary: Hiram already feels the tension between the charismatic and communal world his polygamist parents inhabited and the world his adopted son, Michael, dreams of “when the superstitions of the past would fade away, and scientific theory would be applied to improve all aspects of life” (206).

Gus Dollar, a German immigrant and fellow practitioner of folklore, recognizes the difficult position Hiram inhabits. “The practices that were mandatory when you were a child became the oddities that were winked at when you were a young man, and the crimes that are now prosecuted when you are grown,” he observes. “The world you were born into has disappeared” (77).

“You are not a man of this century, Hiram Wooley,” Dollar notes, unknowingly echoing voices within Church leadership.

“I don’t know,” Hiram responds. “I do like my truck” (78).

And yet, even in the new world, Hiram finds that old problems persist. For him, wearing the yoke of discipleship means using every available means to help those in need. In the mines near Helper, he encounters starving miners, a bitterly divided Kimball family at odds with an ambitious railroad executive, and an ancient loose demon or two to boot. Hiram finds an unexpected ally in a labor organizer named Mary McGill. When a contact of Hiram’s speculates that the demon name “Mahoun” may be related to “Mahan” in the book of Moses, Mary asks what Mahan means and Hiram responds,

“Master Mahan is a sort of title, I guess. It means someone who has learned to kill for gain. To convert human life into wealth.”

Mary snorted. “Well, that’s Ammon Kimball [the mine owner]. And Naman Retting [the railroad executive]. A lot of people turn human life into money.” (239)

As the book escalates, Hiram’s efforts to help the miners transcend the action sequences they are made up of. Butler and Ritchey channel imagery of hidden tunnels and secret rites from nineteenth-century pulp depictions of Mormons (such as those reprinted in Michael Austin and Ardis Parshall’s Dime Novel Mormons) but with the twist that commercial rather than religious fanaticism is the real threat in their telling. The specificity of the way in which one character betrays Mormon polygamous principles is particularly chilling.

Like Butler’s fantastic Witchy War series, The Cunning Man shows what is possible when Mormon writers are willing to engage with Mormon imagery and themes. Surprising and strange, with a lingering richness in its repurposing of religious language and imagery, The Cunning Man deserves to be part of a discourse about who we are, where we’ve been, and what we owe each other as a people.

D. J. Butler and Aaron Michael Ritchey. The Cunning Man. Wake Forest, N.C.: Baen Books, 2019. 312 pp. Paperback: $16.00. ISBN: 978-1982124168.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue