Articles/Essays – Volume 49, No. 4

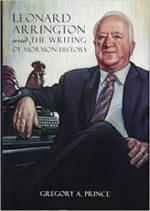

“The Dean of Mormon History”: One Viewpoint | Gregory A. Prince, Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History

Greg Prince published David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism in 2005 to mostly critical acclaim. His study of Mormon historian Leonard J. Arrington is patterned after that work in its style, its largely undigested interpretations, and even its large format size. It did not matter that he never personally knew McKay since the latter was a famed Mormon prophet, but it makes a significant difference in his Arrington book that he never really knew his genial subject. He only met him casually at unspecified Mormon history meetings.

Although Arrington was extremely familiar to Mormon historians and Mormon history buffs, he was not universally known to Mormons in the same way as President McKay. That point is of major significance for Arrington followers who knew him to be a historian of the first rank, a genuine intellectual, and an affable, generous human being.

Prince correctly makes much of the fact that the “Dean of Mormon History” was also an avid mentor to numerous aspiring Mormon scholars. In fact, I was mentored by him. Yet Prince cavalierly demotes Arrington by his description of his numerous writings on Mormon history as “mediocre” and even “abysmal” to read. Astonishingly, this includes his hallmark book, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900, originally published in 1958 by Harvard University Press, and Brigham Young: American Moses, published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1985.

Both books received high marks from scholars of western American history and were ardently enjoyed by rank-and-file Mormon readers. The first book permanently changed the public view of Mormonism as a field of study worthy of pursuing; it may have led to newly-organized departments of religion and endowed Mormon chairs in several universities. The second book was the first objective and scholarly analysis of Brigham Young, the colonizer and pioneer, written in the twentieth century. It has not yet been equaled in the twenty-first century. Previous studies of Young were either viciously anti-Mormon or embarrassingly apologetic. Each Arrington book has been widely used in academic courses in Mormon and western history and by scholars who followed him with their own appraisals.

That Prince refers to Arrington’s published work as “mostly ghostwritten” is stunning, disingenuous, and actually insulting. Toward the end of his book, Prince tries to justify such a description by arguing that while Arrington was LDS Church Historian, he utilized large chunks of material written by his scholarly staff that went unattributed, even though Church authorities insisted that his name be the only one included on his books. Prince also glosses over Arrington’s formidable obstacles in writing during those years because of his copious duties as an administrator.

Prince calls Arrington “naïve” in his dealings with LDS General Authorities, as if to imply that they took advantage of him by going through a back door to overrule his Historical Department decisions. Actually, he often stood up to General Authorities. Prince is dismissive of Arrington’s talks to Mormon groups, alleging that his actor son, James, would coach him how to make a gentle but clever point, i.e. “Just remove your glasses, lean over the podium and say, ‘I’ve been through the archives. I’ve seen it all! There’s nothing to worry about.’” I don’t doubt the quotation, but I don’t think Arrington needed coaching. Prince may not have heard the talks. They were filled with rich anecdotes that made his oral style lively and entertaining.

As a good friend for many years, I witnessed his charismatic speaking ability and candid approach that also spilled over to the LDS study group to which he and I both belonged. He always conveyed his opinions of Mormon history and his differences with Church leaders with conviction and his signature humor.

Although Prince often uses Arrington’s candid diaries and frank letters, he does not always use them effectively. He conducted a variety of interviews with people Arrington only knew casually, but he allows their sometimes confusing views to dilute the primary sources. Some of the extraneous opinions expressed in the interviews appear to be apocryphal rather than stories “from the horse’s mouth.”

I look forward to the promised publication of Arrington’s actual diaries to speak for themselves.

The Prince book fails to do justice to the brilliant man I knew.

Gregory A. Prince. Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2016. 540 pp. Hardcover: $39.95. ISBN: 978-1607814795.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue