Articles/Essays – Volume 43, No. 3

Re-Creating the Bible | William C. Bishop, B. G. Christensen, Samantha Larsen Hastings, Sarah Jenkins, Eric W. Jepson, Ryan McIlvain, Danny Nelson, and Arwen Taylor, The Fob Bible

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Lately the Bible has been getting a bum rap. Christopher Hitchens calls it “a nightmare”and blames it for much of humanity’s suffering—everything from sexism to genocide. At the same time, literalist approaches to the Bible have produced narrow theology and tendentious, unscientific speculation. With these sorts of extremes touted by reductionist pundits and preachers, people are left with a false dichotomy of biblical proportions. Historian of religion Karen Armstrong reminds contemporary readers that “many modern assumptions about the Bible are incorrect. The Bible did not encourage slavish conformity. . . . From the first, the Biblical authors contradicted each other and their conflicting visions were all included by the editors in the final text.”

Consequently, the Bible remains a sturdy and elusive text that withstands pretentious punditry. It is not an infallible guide to the history and future of humanity any more than it is the origin of all the world’s ills. It is a contradictory, literary, and illuminating text, filled with tales, parables, letters, narratives, wisdom, philosophy, and poetry of lamentation and desire. By seeing the Bible whole, we are reminded that it is a literary epic on a par with the Iliad, the Odyssey, or the Aeneid. And like those ancient sources, it has inspired writers from Chaucer and Milton to James Joyce and Cormac McCarthy, among countless others.

Among those influenced are an up-and-coming group of LDS writers who call themselves The Friends of Ben (or Fob for short). Having found each other through classes and conferences, these friends organized a writing group in 2002, which “from the beginning was a meeting of misfits, a place for those who felt somehow outside the day-to-day realities of modern pragmatics” (ii).

The group includes B. G. (“Ben” himself) Christensen, who organized the first meeting, and his “Friends”: Kari Ambrose, William C. Bishop, Matthew Evans, Samantha Larsen Hastings, Sarah E. Jenkins, Eric W. Jepson (also writing under the nom de plume Theric Jepson), Alex Liberato, Ryan McIlvain, Chris Mohar, Danny Nelson, Hannah Pritchett, Christian Sorenson, Arwen Taylor, Sarah Jane Thomas, Josh Weed, and Jeff Windsor.

While discussing their projects and writing ambitions, it was “not puzzling, given the Mormon heritage of the group, that they would have an urge to reexamine fundamental assertions of their culture—some from positions of orthodoxy and others from points far removed” (ii). The “Fob” turned to the Bible in pursuit of these reexaminations, which “often flowered into creative works” (ii), resulting in The Fob Bible.

On opening The Fob Bible, the reader encounters a family tree filled out with the authors’ names, with room to add more. Facing it is an extended title page, with the title of this creative scripture in large ornate letters, followed by the statement “A Quotidian Book of Scripture . . . containing, but not limited to, the juiciest portions of the Old Testament . . . translated through means of memory and nightmare . . .” The title page goes on with little jokes and ironic asides, promising that this “Fully Authorized Fob Version,” may be “of a feminist bent in places, with far too many references to behemoths and leviathans.” By contrasting “quotidian” with “memory and nightmare,” or juxtaposing mythical creatures alongside feminism, the extended title page encapsulates the contradictory, even paradoxical nature of scripture, explored in a spirit of play.

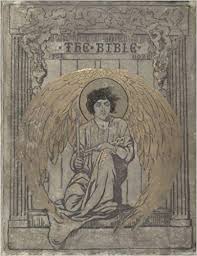

In addition to the title page and following written selections, care has been paid to design and illustration. Each piece is preceded by an illustration, usually by Gustave Doré, along with a caption. Each selection, with no authorial attribution, is then introduced by a quotation from scripture, setting the stage for a creative examination of biblical storytelling. The lack of authorial attribution in the Fob Bible heightens the sense of play within and between the various contributions, reproducing the complexity of the Bible’s wildly varied and ambiguously interrelated texts. An appendix identifies which “Friend of Ben” wrote which individual pieces.

And like the Bible, the Fob Bible comprises a variety of forms: short stories, poems, a play, and other prose forms that cover all kinds of major characters, such as Abraham, Isaac, Esau, Moses, Ezekiel, Solomon, Daniel, even Jeremiah. Many minor biblical characters are given major play by the Fob—Job’s wife, Baal’s secretary, Gomer, Heber’s wife, and even Maher-shalal-hash-baz make more than cameo appearances. There are too many stories to cover in this review, and each one could be discussed in depth, but let me give you a taste of what to expect.

“How to Get Over It, a public service message” is a running series throughout the book in which familiar tales are recounted with deadpan delivery. One is “The Joseph Method,” which begins, “Joseph, who later would use the stage name ‘Joseph of Egypt’ (and, much, much later, ‘Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream coat’), was sold into slavery by his brothers—to a bunch of hairy Ishmaelites no less” (65). It reminds one more of the “Shouts and Murmurs” section of the New Yorker, than of any sort of biblical fiction one might find at Deseret Book.

Another prose piece I particularly enjoyed was “Ezra’s Inbox,” an interaction between priests, prophets, and kings via email ex change, in which King Sanballat, governor of Samaria, complains to Nehemiah, “How do you plan on building a temple? You’re not Solomon! I’m way more Solomon than you are!” (133). The humor is infectious, without being too hip for its own good.

Poetry ranges from serious to silly, including lighthearted verses inspired by the rhyming sounds of Ogden Nash. An enjoy able and pithy lyric that gives a brief taste of one of the many kinds of verse a reader will encounter is, “The Love Song of Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar,” about Job’s “loyal” friends:

If you are sad, we’ll come to you,

if you are sick, we’ll bear you up,

if you have pain, we’ll sit with you

and help you drink the bitter cup.

You’ll never find more loyal friends,

not under heaven’s arching vault!

In trio, we will pass the time

reminding you it’s all your fault.

(161; emphasis theirs)

I suspect that the title of the poem is an intentional reference to the “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T. S. Eliot, which the rest of the poem probably has little to do with. But like the “loyal friend” of the poem, allusions in The Fob Bible are frequently deceptive or ironic.

Another favorite selection, “Blood-Red Fruit,” is a fictional philosophical dialogue between Satan and the serpent. It is partly inspired by the accompanying Doré illustration, depicting a scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost, in which Satan contemplates what form to take while looking upon a snake, “The Serpent sleeping, in whose mazy folds / To hide me, and the dark intent I bring.” Here’s an excerpt, with Satan beginning the conversation:

“You are very beautiful,” he said.

The snake stirred, blinking. “How can you know what beauty is?” she asked. Her voice was low, and modulated. “Only the gods know that.”

Satan shrugged. “I don’t know how I know, snake. I only know that I know—and you are very beautiful.”

“Are you a god, then?” Her voice was cool and musical, like a brook, and she regarded Satan with cool eyes.

He laughed, leaning back into his wings and grabbing his knees. “Do I look like a god to you?”

“You look like half a bat,” said the snake as she eased down from the tree. “The other half might be monkey, might be man. You have more hair that the other two-legs in this part of the tree-place.”

“Not a god though. That’s a relief,” said Satan. He leaned forward slightly and studied her as she moved from under the shadows of the trees. “You are beautiful—look at you in the sunlight. You’re like a living bruise.”

“What part of creation is a bruise?” asked the snake.

“A very beautiful part.” Satan’s mouth twitched into a smile. (15–16)

And this story is just one of the many beautiful parts of this collection, which is no less delightful for the occasional misstep in the dance, where back stories and side stories—only hinted at in the Bible—are filled in by the Fob writers with a sense of pure pleasure.

Though many of these stories have strong elements of entertainment and humor, seemingly done with ironic glee, they also present challenging experiments that remind the reader of what makes the Bible unique. While much religious fiction based on biblical stories tries to water down the inherent strangeness of the Old Testament for the sake of a commercial audience, The Fob Bi ble foregrounds the strangeness. By juxtaposing the strangeness with various literary forms and contemporary approaches, it creates a type of meta-scripture, in which literary truth is exalted over doctrinal correctness.

The Fob Bible reminds us of the literary heritage and strangeness that the Bible contains. It is compelling reading, making one reexamine assumptions about familiar ideas, stories, and characters, discovering that they are neither plain nor precious. The Fob Bible may drive you back into the scriptures, to experience again why the Good Book not only holds religious sway but literary prowess as well.

William C. Bishop, B. G. Christensen, Samantha Larsen Hastings, Sarah Jenkins, Eric W. Jepson, Ryan McIlvain, Danny Nelson, and Arwen Taylor. The Fob Bible. Illustrations by Paul Gustave Doré. Book Design: Elizabeth Beeton. Kansas City, Mo.: Peculiar Pages, 2009. 265 pp. Hardcover: $39.99. Paper: $23.99. ISBN: 978–0– 9817696–9–1

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue