Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 1

Review: R. A. Christmas, Leaves of Sass

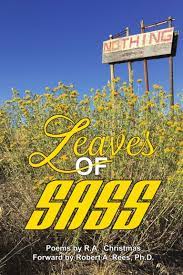

R. A. Christmas. Leaves of Sass. Self-published: 2019. 148 pp. Paper: $19.51. ISBN: 9780359896400.

Colin B. Douglas. Into the Sun: Poems Revised, Rearranged, and New. Salt Lake City: Waking Lion Press, 2019. 292 pp. Paper: $14.95. ISBN: 978-1434104199.

Jan G. Otterstrom F. Move On. Self-published: 2019. 152 pp. Paper: $15.00.

Kate Piersanti. Life in Poetry. San Pablo, Calif.: Headland Productions, 2020. 108 pp. Hardcover: $19.95. ISBN:9780578573083.

It has been more than a month since I’ve visited a grocery store or my ward building as this series of reviews is being written. Sacrament meeting has migrated to the web and my parents and siblings have been more in contact than usual. Exercise consists of walking across streets to avoid neighbors on the same sidewalk. And much of my thoughts have been directed to those at the greatest risk.

Even before social isolation kicked in, I had planned to group these four collections together, simply because they are all written by older writers, each of whom, to some degree, is staring age and mortality in the face with the structure and intent of their latest works.

Christmas, I believe, is the eldest, and in his introduction, he sets an exaggerated stage for a twilight collection. He leaves the impression that he is more concerned with getting every poem that’s left in him to print without worrying too much whether they are quite ready. Which is not to say there are not excellent poems in the collection. The final two poems in particular—the twenty-four-page “Taps for the BSA” and his thirty-one part translation of Paul Valéry are both excellent.

Sass thus makes for a frustrating read. Some poems are excellent, some are rough drafts, passing thoughts that could have been the raw material of something better. When he takes on a form (e.g., the sonnet), Christmas tends to do better work—the constraints force him into greater care.

A similar crisis of volume devalues Otterstrom’s latest collection. It too has occasional flashes of excellence buried by everything else. Otterstrom even labels each poem with a date, presumably the date it was written then forgotten. This is frustrating. Two poets of great merit with a lifetime of excellence behind them. Two collections that garnered introductions from fellow poets of merit and skill who admire their body of work. Yet two collections that aren’t really collections at all, but hurried shoveling as the ultimate deadline looms.

A different but related issue comes into Douglas’s collection, which includes a lifetime of poetic work dating back to 1979. The poems often revisit and renew old themes, yet here each poem has been crafted into a final form. One can argue that the poems are too many when you have over thirty discussing alphabets/letters/glyphs, or when you have about ten featuring crystals and ten featuring spheres, making about five with crystal spheres, at least two of which grow inside someone’s breast. It’s not that I can easily declare one of these poems superior to another—each poem is a crafted marvel worthy of our attention. It’s more that this is a collection to spend years reading (rather than the ten days I spent) in order for them to layer rather than suffocate. Or, perhaps, this is a collection that could have been refined had the poems already been out in the world, only the fittest surviving.

Startlingly different in form from the above collections is Piersanti’s Life in Poetry. Shaped and illustrated and designed like the sort of gift book you might find at a grocery store (if we still went to grocery stores) next to the get-well-soon cards, Piersanti’s second collection almost Reviews 169 feels as if it is in disguise. The poems often skirt against the sort of sentimentality expected from poems printed atop photographs, but the collection as a whole stares directly at such themes as sex, pain, spiritual hope, and confusion. The combination makes for a frisson I could never resolve.

In the end, all four made me think about other recent collections I’ve read from twilit authors—the likes of Donald Hall or Billy Collins. And each of these four books suggests the same conclusion: the poetry ecosystem they are part of has not provided them with the same editorial tools that made Hall’s or Collins’s collections so strong. Having read these collections, I’m convinced that all four are excellent poets— excellent poets without a support system consisting of years of sufficient input and feedback to help them reach their fullest measure. Christmas offers thanks to “Lulu, my self-publisher for over twenty years, for helping me keep my literary output at least marginally accessible.” And Douglas has written that he withdrew from attempting to publish after 1989 (thirty years ago!). And why? Because he had decided “to write openly and unapologetically from my experience and sensibility as a Latter-day Saint, however that might restrict my readership and prospects for publication.”1 Which, as any Latter-day Saint writer so decided can tell you, it certainly may.

And so we have four writers who—not to be morbid, but we are in the midst of a global pandemic aimed directly at the elderly—may have just published their final collections. Three of them self-published, and the fourth has been published by a press owned by a one-man software company that otherwise focuses on work in the public domain. This is not an ecosystem designed to help our poets leave behind great legacies. It feels more like “a fatal, irretrievable ending” (Otterstrom, “Lose Oneself,” 19) as we all look away.

Our poets deserve better.

1. Colin B. Douglas, “Colin B. Douglas on ‘Into the Sun,’” Dawning of a Brighter Day (blog), Feb. 28, 2020, http://associationmormonletters.org/blog/2020/02 /colin-b-douglas-on-into-the-sun/.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue