Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

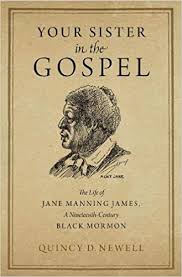

Remembering Jane Manning James Quincy D. Newell. Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, a Nineteenth-Century Black Mormon

In this carefully researched work, Quincy D. Newell produces a powerful narrative of Jane Manning James’s life from limited records. Newell reveals what life was like for someone like James, whom she refers to as Jane throughout the text, showing the intersections of her racial, gendered, and religious identities and the various systems of oppression she encountered. Newell masterfully guides her readers in Your Sister in the Gospel, providing a fresh perspective on Mormonism from the view of an African American convert in the nineteenth century. Jane’s perspective, Newell argues, shows a form of Mormonism focused on supernatural religious experiences rather than on priesthood and temple rituals. It was these experiences that made Mormonism appealing to Jane. Newell begins and ends her work with the observation that Jane wanted to be remembered. With the increased interest in Jane Manning James in the recent decades, this biography is an important addition that shows the intricacies of her life. Newell carefully makes conjectures to consider how Jane felt about her circumstances, and she intentionally refers to her by first name throughout the text to focus the history on her rather than the men in her life. By centering Jane in the narrative, Newell helps her readers remember this historical figure in all her complexity.

One of the greatest strengths of this book is how the author weaves Jane into the larger context of her time. Since there are such limited records on Jane herself, Newell uses contemporary documents from Jane’s peers, including accounts from other African Americans, women, and Latter-day Saints, to further her observations of Jane’s life. Scholars who are more familiar with the secondary literature on African American history, American women’s history, religious history, and Mormon history will appreciate how well Newell includes material from these many fields to create a strong portrait of Jane. Newell seamlessly incorporates important arguments into her text. For those less familiar with these fields, her footnotes are filled with helpful references that can open opportunities for many readers to learn more about historical scholarship. Newell uses words such as “perhaps” and “likely” to signal to her readers when she pulls from this larger body of scholarship to help illuminate Jane’s life and actions.

Jane was born in the Northern United States in a period when this region was attempting to forget their history of slavery but nevertheless had an enduring ideology of white supremacy. Jane and her family had to grapple with this daily, as Jane worked as a domestic servant, possibly indentured, in Connecticut. It was during this time that Jane gave birth to her first child, though she kept silent about the circumstances in later accounts of her life. This is one such moment in the text where Newell considers this silence and suggests possible readings of Jane’s circumstances. Newell also explores Jane’s religious conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1842, speculating on which factors led to her baptism. Newell observes that Jane was “making her own beginning” with this conversion (22). This theme of new beginnings continues to emerge in Jane’s life moving forward.

Jane’s journey to Nauvoo shows the difficulties of traveling in the United States for African Americans during this period. Jane and her family took significant risks in this migration, encountering discrimination, black codes, and the risk of enslavement. Newell carefully traces their journey, and their possible routes, bringing the realities of their trek to life. She then considers what Nauvoo was like for them as they encountered the racial positions of the Church. Nauvoo held a central place in Jane’s narratives of her life. She centered her accounts on this short period (less than a year) of when she lived in Nauvoo, and her experiences with Joseph and Emma Smith. Newell also observes that Jane’s labor in their home is what made it possible for the Smiths to be hospitable community leaders. Her work in the Mansion House also means she possibly observed interactions and evidence of plural marriage. It was in Nauvoo that Jane received her first patriarchal blessing, a document she treasured for the rest of her life. Newell recreates the journey west for Jane and her husband, Isaac James, by looking at correspondence and diaries from their company. The James family made it possible for George Dykes to join the Mormon Battalion, as their labor supported his three wives. Once they reached Salt Lake City, another new beginning, the James family labored to support Brigham Young and his family. Time and again, Jane’s labors made particular moments and practices within Mormonism possible.

Newell explores Jane’s religious experiences in more detail for the rest of the book and shows how Jane’s race and gender informed her religious convictions and practices. Newell uses the James family to illustrate the experiences of the African American community in Salt Lake City, particularly in a period where positions on race and slavery were being debated in the territory. Racial restrictions on the priesthood and the temple made it so that Isaac could not live up to the ideal masculinity of the Church. Newell considers how these restrictions and Jane’s life experiences—including the string of losses of her children, some of whom died while others left the Church—created a desire in her to live up to the ideal femininity of the Church. Jane attended her meetings, including Relief Society and Retrenchment meetings. Newell finds these wonderful hints into Jane’s spiritual life through these records, showing how important these minute books are for uncovering the lives of women in the early Church. Within these records, Jane speaks in tongues, bears testimony, and gives accounts of faith healings. Jane also performed baptisms for the dead. Newell traces these spiritual practices as she also narrates the development of temple restrictions that limited what rituals Jane could do, making it so Jane’s family could not be together in the afterlife.

As Jane got older, this belief that she would not reach the highest glories in the afterlife bothered her more. Newell analyzes in detail Jane’s letters to various Church leaders and the continued conversations she had as she asked where the blessings were for her. The interpretations in this chapter of the book are particularly strong, as Newell pulls together such a variety of evidence, showing Jane’s family connections, her petitions, and her religious participation. Jane enlisted the help of her Relief Society sisters for her cause. Newell considers what type of eternal family Jane envisioned, contrasted with that of white Church leaders. Her continual petitions made it so that Church leaders had to grapple with these racial restrictions and what their repercussions might be. They compromised and created a new ritual. Newell explains that this ceremony was an “unsatisfactory compromise” for both Jane and these Church leaders (115). Jane had wanted to be adopted as a child, attempting to create a heavenly family that could fit LDS ideals, but Church leaders had attached her as a “servitor” to Joseph and Emma Smith instead. They were connected, but not quite family. Newell juxtaposes this ceremony, which Jane was not allowed to attend, with Jane’s unusual request the following day in Retrenchment meeting for her patriarchal blessing to be read in full. Even as she was excluded from the temple, Jane wanted the promises made to her to be known.

Newell finishes her account of Jane’s life by looking at how Jane made her memories and life a part of the public record. Joseph Smith was central in the accounts of her life story. Her memory of Smith was used in this period by Church leaders and by Jane to paint different pictures of the prophet. Church leaders worked to change the memory of racial restrictions and say that those practices were rooted in Smith. Jane gave an alternative perspective of a racially progressive prophet, but this position was marginalized. Newell considers how Jane was seen in the community, particularly in how she was called “Aunt Jane.” This was a way to show respect and honor, but it also had racial connotations. Newell argues that like her sealing in the temple, this name connected her to the community while also putting her in a subservient role. Jane wanted to be remembered but was then forgotten. Her story was reimagined in the twenty-first century as the Church attempted to grapple with its racial history.

This book convincingly shows how Jane’s life troubles our typical narratives of the nineteenth century. As an African American woman who joined the LDS Church and migrated west, Jane’s life touches on many fields in US history. Jane’s intersecting identities as an African American, a woman, and a Mormon bring up important questions on race, gender, and religion. Newell invites her readers to participate in further work by including the narratives of Jane’s life in an appendix, along with her patriarchal blessings. This is a commendable move. Some readers might not agree with particular extrapolations Newell makes from the limited records, but she invites further discussion with the inclusion of these sources. Your Sister in the Gospelprovides a fresh perspective of Mormonism in the nineteenth century. Scholars interested in African American history, American women’s history, American religious history, and the history of the American West, will find much here that furthers scholarship in these fields. I look forward to seeing the additional works that emerge as a result of this engaging biography.

Quincy D. Newell. Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, a Nineteenth-Century Black Mormon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. 203 pp. Hardcover: $24.95. ISBN: 978-0199338665.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue