Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 4

Rebranding the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Chinese-Speaking Regions

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the HTML format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. Also, as of now, footnotes are not available for the online version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version, the PDF provided at the bottom of this page, or the PDF on JSTOR.

During the October 2018 general conference, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints President Russell M. Nelson denounced the use of common nicknames of the Church such as Mormon and LDS, as they, in his view, offend Jesus and please Satan. His pronouncement ignited the latest debate about what the Church should be called and how members should identify themselves. Less well-known is that similar branding issues exist outside of English-speaking regions. Members in the Chinese-speaking world (mainly China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau) have dealt with their own Church branding problems for many years as well, particularly in regard to how the Church’s name and the title of the Book of Mormon should be translated. An effort was undertaken in late 2000 to address the issue, and the Church’s Chinese name was officially changed on January 12, 2001. Six and a half years later, on August 22, 2007, with a new translation of the triple combination, the title of the Book of Mormon was also changed.

This paper deals with the issue of branding and translation in the context of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Chinese regions. Some saw the original titles as roadblocks for the Church to reach millions of potential converts in China and advocated for the name changes. Others were reluctant toward the proposal, insisting on the accuracy of the original translations and fearing that the changes might undermine the Church’s hard-earned, long-built reputation in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. I first provide a brief historical review of the Church’s development in these Chinese areas. I then discuss the notion of branding and the intricacy of translation, especially from a phonographic language (e.g., English) to a logographic one (e.g., Chinese). The main objective of this paper is twofold: to lay out the debate and process of the name changes and to discuss the fallout and implications of the new branding. As these changes aim to make the Church more acceptable, the conclusion looks toward the future by identifying some challenges and prospects of Mormonism in China.

The LDS Church in the Chinese Region

The Church had China in mind as a mission field as early as 1849, but the plan did not materialize until a conference held in Salt Lake City in August of 1852. Twenty-eight missionaries were called thereafter to proselytize in China, Siam (Thailand), Australia, and India. Among them, four were to go to China. Due to Walter Thompson’s illness, however, in the end only three—Hosea Stout, James Lewis, and Chapman Duncan—actually arrived in Hong Kong on April 28, 1853. Mid-nineteenth-century China was in turmoil, facing both external foreign invasions (e.g., the Opium Wars) and internal social instability (e.g., the Taiping Rebellion). Hong Kong at that time was over a decade into British colonial rule (1841–1997) as the result of the first Opium War.

The first LDS mission in Hong Kong was very short-lived; it lasted a bit shy of two months. Missionaries left to return home on June 22, 1853, citing various obstacles. Targeting mostly Caucasians then, the three elders found most European businessmen uninterested in religion and British soldiers “immoral and corrupt.” Unfamiliar with the culture, holding racial prejudice, and unable to communicate with the local population, the missionaries were treated with suspicion, probably seen by locals as 鬼佬 (“gwai louh” in the Cantonese dialect, meaning “foreign devils”), like all other white invaders. A few more missionaries were also called to the China Mission in April 1853. But word of the first batch of missionaries’ intention to return had been spread before the trip; the second group thus did not even leave for Hong Kong, based on the assumption that their efforts there would be useless. In evaluating the failed initial attempt in China, historian Xi Feng laid blame mostly at the institutional level, suggesting that the Church did not provide enough support for missionaries in funds and language training.

The Church did not deal with China for almost six decades afterward until it agreed to sponsor an exploratory trip in January 1910 by two missionaries, Alma O. Taylor and Frederick A. Caine, who had recently finished their missions in Japan and were on their way home, taking a route through Korea and China. Seeing political unrest still rampant, they recommended that the Church “postpone the opening of a mission in China until the present chaotic, transitory state changes sufficiently to assure the world that China really intends and wants to give her foreign friends protection and a fair chance.”

A decade later President Joseph F. Smith sent David O. McKay and Hugh J. Cannon on a yearlong world trip in late 1920 to evaluate various regions for potential missionary work. They arrived in Beijing in early 1921 and immediately formed a pessimistic view regarding the prospect of reintroducing the gospel there. McKay observed:

China is a disintegrating nation. China is a mercenary nation. China is a land of beggars and parasites! China appears to be made up of not a religious but a superstitious people. . . . The Chinese people cannot be successfully Christianized by the usual missionary propaganda.

Nevertheless, McKay dutifully gave a dedicatory prayer to bless the land in a small grove in the Forbidden City on January. In it he described China as a “benighted and senile nation,” its people “bound by fetters of superstition and false doctrine.” He thus prayed for “peace and stability to be established throughout this republic, if not by the present government, then through the intervention of the allied powers of the civilized world.” McKay also asked for heavenly mercy to release Chinese people from famine, starvation, and “the darkness of the past” through “thy chosen servants . . . with Glad Tidings of Great Joy.”

Nearly three decades later, in 1949, the Communist Party emerged victorious from China’s civil war, forcing the Nationalist government to escape to Taiwan and many refugees to Hong Kong. It is noteworthy that the Church decided to send missionaries back to Hong Kong at this juncture, in 1950, nearly a century after the initial missionary effort. Fearing Communist expansion and the Korean War, however, the Church withdrew missionaries from Hong Kong again not long afterward and did not resume the work until 1955. The next year, four missionaries were sent to Taiwan, and about ten years later the Chinese Book of Mormon was published in December 1965. The Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price were subsequently translated, in 1974 and 1976, respectively. The Taipei Taiwan Temple, the first LDS temple in the Chinese region, was dedicated on November 17–18, 1984 and the Hong Kong China Temple on May 26–27, 1996, before the handover of the island city back to China on July 1, 1997. The Church has experienced modest but steady growth overall in both Taiwan and Hong Kong. As of February 2020, the Church website counts 24,933 members in Hong Kong (1 in 297 people are LDS, or about 0.34% of the total population) and 61,034 in Taiwan (about 1 in 386, 0.26% of the total population).

The Church in modern China took a different path. The Communist Party proclaimed the state atheistic after its political takeover in 1949. It implemented the three-self principle—self-administration, self-support, and self-propagation—in regulating religions to prevent foreign interference. Religion was severely suppressed during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) with countless believers persecuted and places of worship destroyed. The Church saw the door begin to open after China announced establishment of diplomatic relations with the United States in late 1978. President Spencer W. Kimball anticipated the prospect of proselytizing to a billion Chinese souls and thus strongly encouraged members to learn Mandarin. In the meantime, the Church began a series of cultural exchanges in hopes of gaining a foothold there. For example, Brigham Young University performance groups started touring China in July 1979. Six children of top-ranking government officials, including the daughter of Premier 趙紫陽 (Zhào Zǐyáng), kicked off an ongoing study program at Brigham Young University–Hawai‘i and the Polynesian Cultural Center in 1980. Russell M. Nelson, then a cardiovascular surgeon, was invited to lecture on open-heart surgery and conduct operations at various medical institutions in China, including the Shandong University School of Medicine, in the early 1980s.

These friendship-building activities led to a meeting between high-level Church authorities and Chinese government officials in January 1989. Upon returning from China, Russell M. Nelson and Dallin H. Oaks proclaimed that “the door to China is already open”:

We were assured that the people in China or Chinese citizens who are abroad are free to join any religious denomination they choose and to practice the tenets of that religion in China without fear of repression. . . . You can be a Latter-day Saint and live in the People’s Republic of China, and you won’t be isolated from your fellow members of the Church or penalized for your beliefs.

As a non-state-sanctioned religion, the Church, in return, promised not to disobey China’s laws through formal missionary proselytizing activities. This relationship has since become the status quo. While clarifying rumors of sending missionaries there through alternative paths, Nelson reaffirmed in 2012 that the Church will enter China “through the front door. We do not go in through the back door or via the alley. Our relationships are based on honesty, openness, integrity, and complete compliance with local law.” Due to political sensitivities (explained later), there are no publicly available membership statistics on China at this point. In terms of Church resources, selections of the simplified-Chinese-character Book of Mormon were published in 1983, and the full-length version was made available in 2001. Though not a prominent issue among most English-speaking Latter-day Saints, branding and translation have been key elements within the expansion of the Church into the Chinese region.

Branding and Translation

The purpose of branding is to distinguish one’s own product from other similar offerings and thus to attract consumers. General rules of thumb for good brand names include simplicity, distinctiveness, meaningfulness, recognizability, and pronounceability. Corporations build brand images by associating themselves with positive traits and symbolism, such as sophistication, excitement, competence, progress, freedom, and so on, in order to stimulate purchases. Not-for-profit organizations increasingly also rely on carefully cultivated brand images to compete for donations. Religion has a long and inseparable relationship with branding and marketing in the United States. The First Amendment of the Constitution guarantees religious freedom, precludes a state-sanctioned creed, and thus lays the foundation for the marketization of faith. In order to survive in the competitive marketplace, different religions build their own brands; some even adopt business strategies to sell their versions of god, truth, and salvation. It is little wonder that many Christian ministers, or their immediate descendants, were among the pioneers in the fields of advertising, marketing, and public relations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, since its birth, is no exception to the brand-building impulse. The Book of Mormon and other modern scriptures, latter-day prophets, temples, and the Word of Wisdom are some elements of the faith’s branding. “The Homefront” TV commercial series in the 1970s and ’80s cemented the Church’s family-oriented image. The more recent “I’m a Mormon” ad campaign attempted to combat the Church’s perceived “cultish” stereotype by featuring cool, likable members other people can relate to.

The issue of translation is crucial when a brand (commercial or otherwise) reaches an international market. The general debate has been over standardization versus localization. Ideally, a brand should hold a uniform, consistent image worldwide. Language barriers and unintended meanings or connotations conveyed in other cultures make this ideal difficult to achieve. Local adaptation, although costly and sometimes deviating from the original brand image, is often unavoidable. The fabric softener Snuggle, for example, is marketed as Cajoline in France, Yumoş in Turkey, Kuschelweich in Germany, Coccolino in Italy, and Mimosin in Spain. These names are not necessarily word-for-word translations, but all convey images of softness, gentleness, and caressing that the original brand attempts to project.

When translating a brand name, marketers generally consider three methods: by sound (phonetic translation; e.g., from Audi to 奧迪 [ào dí] and Kodak to 柯達 [kē dá]), by meaning (semantic translation; e.g., from Microsoft to 微軟 [wéi ruǎn] and Apple to 蘋果 [píng guǒ]), or by combining both (phono-semantic translation; e.g., from Goldlion to 金利來 [jīn lì lái; “gold” is semantically translated to 金, but “lion” is phonetically translated to 利來, which literally means “profit come”]). A wild-card creative translation method can be employed when neither sound nor meaning works (e.g., from BMW to 寶馬 [bǎo mǎ, meaning “precious horse”]). In any case, scholars suggest that cultural factors and consumer perceptions should always be taken into account.

These simple guidelines, however, become more complicated when translating from a phonographic language, in which words are composed of sound-based letters, to a logographic one, in which words are composed of signs or characters. English is a phonographic system; each syllable has a sound but not necessarily a meaning. Chinese, on the other hand, is logographic; each character almost always carries at least one meaning, but the character itself often gives no clue as to its pronunciation. Chinese tones and homonyms (one character with multiple meanings or pronunciations, or many characters sharing one pronunciation) make the language even more intricate and difficult to translate into. Based on the pocketsize dictionary I own, for instance, there are at least thirteen commonly used characters associated with the Mandarin sound “shī” (the first tone alone): 師 (teacher), 施 (give), 失 (lose), 濕/溼 (wet), 詩 (poem), 獅 (lion), 屍 (corpse), 蝨/虱 (lice), etc. When considering the three other main tones, the total number of distinctive characters that share the “shi” sound jumps to seventy-two. As a result, when translating a brand name from a phonographic language to Chinese, one has to take not only sound or meaning into account but also which character of the same or similar sound to use. For consumer goods, words with positive connotations and appropriate associations with the nature of the product are naturally preferred.

Take Coca-Cola as an example; its Chinese name is regarded as a textbook case of successful translation. When first introduced to China in 1927, as the legend goes, shopkeepers put out signs with random phonetic words such as 蝌蚪啃蠟 (“kē dǒu kěn là,” meaning “tadpoles bite the wax”) to promote the product. The official translation 可口可樂 (“kě kǒu kě lè,” meaning “delicious happiness”) was trademarked one year later. Based on principles of phonetic translation, it follows the original pronunciation very closely. More importantly, the characters evoke a strong satisfaction of the mouth (note that there are three mouths [口 “kǒu”] in the phrase) as well as the emotion of happiness (樂 “lè”). Coca-Cola paved a way for its competitor Pepsi-Cola (百事可樂 “bǎi shì kě lè”) in Chinese markets, connotating a sense of happiness in one hundred/all things.

The translation for Revlon (露華濃 “lù huá nóng”) is also widely seen as top-notch. 露 literally means “morning dews” or “to reveal”; 華 means “magnificent,” “splendid,” or “flowery”; and 濃 “thick,” “dense,” or “full.” The ingenuity of this translation resides in more than just its proximate sound to the original pronunciation and the pleasing picture each character paints. The phrase actually comes from a famous poem 清平調 (“qīng píng diào,” which I translate as the ballad of purity and tranquility) by arguably the most talented poet in Chinese history 李白 (Lǐ Bái), describing the Tang Dynasty’s most beautiful woman 楊貴妃 (Concubine Yáng), beloved by 唐玄宗 (Emperor Xuánzōng). The name is simply perfect for a cosmetic brand.

Church Branding Issues in the Chinese Region

As mentioned earlier, the LDS Church’s Chinese name and the Book of Mormon’s Chinese title underwent a translation makeover in 2001 and 2007, respectively. So why the name changes? What was the problem with the original titles? For the Church’s name, the key issue resides in how to properly translate the phrase “Latter-day.” In English, dictionaries define that phrase as “modern,” “recent,” “current,” or “contemporary.” It refers to “a modern version of someone or something from the past.” The original Chinese translation was 末世 (mò shì). 末 (mò) literally means “end,” “final stage,” or “latter part.” 世 (shì) means “world,” “generation,” “era,” or “lifetime.” Together the phrase is often understood as “the last phase” or “the final period.” It connotes “end times” or “the end of the world” and therefore has an apocalyptic feel to it. Some say it reminds people of radical Christian groups who hold signs warning about the coming end of days on downtown street corners.

The new translation is 後期 (hòu qí). 後 (hòu) means “back,” “behind,” “after,” or “later.” 期 (qí) means “a period of time,” “phase,” “stage,” “later times,” or “to hope.” The phrase is therefore often used for “late stage,” “later period,” or “post period.” Proponents of this new translation argue that this term reflects more closely the meaning of “Latter-day” in English, with a restorationist tilt to it. A point of comparison: the Japanese and Korean translation of “Latter-day” was 末日 (mò rì; 日 means “day,” “sun”), almost an equivalent to the original Chinese translation, if not more limiting or urgent, implying “the last day(s).” In Korea, the Church’s name changed from¸말일 (末日 pronounced “mal il” in Korean) to 후기 (後期 “hu gi”) in 2006. The Church in Japan, however, has continued to use the original translation.

In the case of the Book of Mormon, the original Chinese title 摩門經 (mó mén jīng) can be considered a phono-semantic translation. The phrase 摩門 (mó mén) has no intrinsic meaning in Chinese; it is used simply for its phonetic association with “Mormon” in Mandarin. 經 (jīng) has a definite meaning, referring to “classics,” “sutra,” or “scriptures.” Together 摩門經 reads “Mormon scripture,” like Bible as 聖經 (shèng jīng), meaning “holy scripture.” Unfortunately, 摩門 not only sounds exactly the same as but also looks very similar to the different term 魔門 (mó mén, meaning “the devil’s gate/door”). It does not take much imagination for people to connect the two together, particularly in the context of religion. The term also sounds like 無/沒門 (muo meng, meaning “without/no door”) in the Taiwanese dialect.

The new 2007 translation pronounces the “r” in Mormon, which was omitted in the original translation. The new title thus becomes 摩爾門經 (mó ěr mén jīng). The “ěr” breaks up “mó” and “mén” and thus softens the “devil’s gate” implication to a degree. 爾 (ěr) literally can mean “you” or “thus,” but it is not a common word in everyday life. Instead, it is often used in translated foreign names such as 查爾斯 (chá ěr sī, for Charles) or 希爾頓 (xī ěr dùn, for Hilton). The inclusion of the word in a proper noun, as with the Book of Mormon, almost always carries a sense of foreignness. The change, however, does not totally solve the problem the original name had because 爾 (ěr) sounds very much like 兒 (ér, meaning “child” or “son”) in Mandarin, with only a tone difference. The new translation merely shifts the sound from “the devil’s gate” to “the devil’s son’s gate” or “evil child’s gate.” Thus, the new translation has not made things more difficult for mockers.

Negotiating Identity Politics in Name Changes

Even with negative implications, however, most people do not hold the troublesome titles against the Church; they are mostly used within inoffensive jokes, if at all. Some people I talked to in Taiwan said that they had not even thought about the devil’s gate connection. After all, the Church has had modest success in the past half-century-plus in both Taiwan and Hong Kong using those titles. But what triggered the name changes? Who initiated the process? What did it attempt to achieve? Whose voices were present? How were different interests negotiated? Who had the final say? How was the idea communicated to Church headquarters? How has the local general membership reacted to the changes? In late 2018 and early 2019 I interviewed a few key players in both translation changes to explore these questions.

Chinese Official Name Change

The central figure is 賈居仁 (Jiǎ Jūrén a.k.a. Chia Chu-jen), whose family migrated from 安徽 (Ānhuī), China to Taiwan with the Nationalist government in 1949 when he was a teenager. He worked in Canada after college and joined the Church there. He went to graduate school in Toronto and was later called to the Toronto Ontario Stake presidency in the 1980s with a recommendation from M. Russell Ballard. In a 2008 speech at BYU–Hawai‘i, Ballard recalled that he felt inspired “by the power of God” when he first met Chia in Canada “that the Lord would open the way and that within a short season he would be transferred to his native country, the People’s Republic of China, where he would take on the great work of establishing the Church.” Chia’s company later sent him to China, where he served the Church for thirteen years as an Area Seventy starting in 1996.

Chia’s lobbying effort for name changes can be traced back to the late 1990s. His Church calling required him to be in contact with government officials, particularly those from the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA). In 1998, he and John H. Groberg, then Asia Area President, invited several high SARA officials to tour Salt Lake City and Hawai‘i. Treated as VIPs, especially at BYU–Hawai‘i and the Polynesian Cultural Center, these Chinese officials were impressed with the Church. However, they were concerned about the names of the Church and the Book of Mormon. The visitors suggested that although 摩門 (mó mén) also sounded bad in Chinese, in comparison to the official name 末世 (mò shì), the Church might have better luck registering with the nickname than with the official name.

A short digression into Chinese history helps explain why Chinese officials were concerned with the name. China has experienced a long history of millenarian religious unrest, including the Yellow Turban Rebellion (184–205 CE), the Celestial Masters Uprising (or the Five Pecks of Rice, 186–216 CE), the White Lotus movements (for example, 1352–1368 CE; 1796–1804 CE), and the Taiping Revolution (1850–1864 CE). In attempting to build ideal new societies, these movements weakened or even toppled dynasties such as Han (206 BCE–220 CE), Yuan (1279–1368 CE), and Qing (1644–1911 CE). Falun Gong, a contemporary qigong exercise–based quasi-religious organization, is viewed by many as operating out of this tradition. It embraces an apocalyptic end-days theory and is critical of the Chinese Communist Party. As a result, Falun Gong has been deemed an evil religion and a heresy by the government and has been subject to government crackdown since the late 1990s. Against this backdrop, a faith attempting to enter China with a last-days, millenarian focus, such as the LDS Church, was naturally greeted with suspicion.

After the Chinese officials’ visits to Salt Lake City and Hawai‘i, Chia was determined to have the Church’s and Book of Mormon’s titles changed in Chinese. To him, these were translation errors. He felt it should be easy to persuade Church administrators to correct the translations. He consulted with Groberg not long after the trip and, to test the waters, sent letters to local Church leaders in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China (most of whom were non-Chinese at that time). To his surprise, the opposition to name changes was overwhelming, especially from Taiwan, as most believed that the original translations were inspired by God and were not human mistakes.

After the initial setback, Chia turned higher up to M. Russell Ballard, with whom he had a personal relationship. But at that time, Dallin H. Oaks oversaw the translation department. Apparently, the issue had been raised before. Oaks showed Ballard and Chia previously filed proposals for name changes and suggested that Chia put the issue to rest. Chia was not deterred, however. In a July 30, 1999 letter to Neil Glad, supervisor for the Chinese translation team at the Church’s translation department, he outlined a few items of mistranslations identified by a team in charge of translating the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price into simplified Chinese and proposed that the Church correct errors in the sacrament prayers and the Church’s official name. His request was not answered, however.

One year later, with a reshuffling of the General Authorities’ responsibilities, Ballard took over Oaks’s duties, including overseeing the translation department. Chia saw an opportunity and brought up the issue again. In a follow-up letter to Glad on July 3, 2000, he urged the Church “to remove these stumbling blocks” and not “allow the same mistakes made in Taiwan and Hong Kong [to be repeated] in the Mainland of China.” Chia made it clear that his name change effort aimed mainly at the Church’s potential development in China. Anticipating the publication of the Chinese Book of Mormon in simplified characters, Chia reasoned that many copies could end up in China with returning Chinese converts overseas. Therefore, it was crucial for the Church to change its Chinese name before the Book of Mormon spread so that potential investigators would recognize the Church of “latter-day saints” rather than “last-day or dooms-day saints,” as he phrased it.

Chia called for a meeting in late 2000 with a handful of local priesthood leaders and representatives from the Church’s translation department in Taipei to discuss the name change issue. He insisted that the original translations were inadequate and explained to the group the difficulties the Church faced in China due to the negative implication of the term 末世 (mò shì) in general and its unfortunate connection with the Falun Gong movement in particular. Chia added that without a formal Church organization, Chinese members who converted to Mormonism overseas may not stay active when they returned to China. The group considered all possible Chinese terms related to “latter-day” and at the end it came down to either keeping the original translation or changing it to 後期 (hòu qí). The group took an anonymous ballot, and the result was one vote shy of being unanimous to change.

蔡琳 (Cài Lín a.k.a. Casandra Tsai), then director of the translation department in Taipei and the only woman in the meeting, confessed to the group that she was the one who voted against the proposal. While understanding Chia’s position and the potential issues in China, she had two objections to the name change, both from a linguistic perspective. First, she disagreed that the original translation was an error. To her, 末世 (mò shì) does not necessarily narrowly imply a doomsday scenario because the word 世 (shì) also refers to “generation” or “dispensation” in addition to “the world” (as in “end of the world”). The phrase should be understood as the last or latter “dispensation,” which is what “latter-day” can also mean in English. She also pointed out that the original translation of the Church’s name had the blessing of Master 林語堂 (Lín Yǔtáng), the most celebrated linguist and philosopher in Taiwan’s modern history.

Tsai’s second objection resided in the use of the phrase 後期 (hòu qí) in this specific context. It is either unclear grammatically or cannot stand independently. The term usually refers to the later stage of a time period, such as the late 1950s, or as a prefix antonymic to “pre-,” for example as in postmodern or postfeminism. Neither of these two cases work well for the Church’s name in Chinese because they indicate that the LDS Church was restored either during the latter stages of Jesus’ life or right after his death. She felt that the Church’s name should not be changed in the absence of a better alternative.

Tsai said that she knew at least two other people in the meeting voted for the change simply because of their consideration of the Church’s potential development in China, even though they were not entirely satisfied with the prospect of the name change. I tried to interview a couple of leaders who also attended the meeting. But being formal local Church leaders, they were tight-lipped, carefully avoiding disclosing their personal opinion or meeting details.

The meeting adjourned without a clear solution. Cree-L Kofford replaced Groberg in 1998 as the Asia Area President and confronted the name change issue head on. He started to meet with local stake and district presidents to solicit their thoughts. Tsai was appointed to translate for these meetings. Kofford also consulted with a well-regarded non-LDS professor from Taiwan for a more objective view. In the meantime, Chia Chu-jen met with David Frischknecht, director of Church’s translation department, in Beijing on November 6, 2000 under the direction of Ballard. Frischknecht took Chia’s suggestion back to Salt Lake City.

Two months later, a letter dated January 12, 2001 from President Boyd K. Packer was received and announced in sacrament meetings throughout Taiwan regarding the immediate change of Church’s name in Chinese, replacing 末世 (mò shì) with 後期 (hòu qí). This letter came as a surprise to most, including Kofford, according to Tsai, as he was still in the early stages of meeting local leaders in Taiwan (and presumably in Hong Kong and Macau as well). Packer’s letter suggests that the decision was made “after careful consideration and review by translators, ecclesiastical reviewers, and local and General Authorities.” Chia said that in normal circumstances, recommendations usually come from the grassroots and work their way up through bureaucracy to Church headquarters (as Kofford was apparently trying to do). However, this case seems to suggest a top-down decision, affected by Chia’s recommendation. Tsai said that although she held a different perspective regarding the name change, as a Church employee her duty was to obey and follow instructions.

The Book of Mormon Name Change

With one issue taken care of, Chia started to work on changing the title of the Book of Mormon. Just as with the Church’s name in Chinese, problems with the negative connotation of the Book of Mormon’s title had been raised before, especially by members in Hong Kong. According to Tsai and 梁世威 (Liáng Shìwēi a.k.a. Karl Liang), former manager of Taiwan’s translation department, President Gordon B. Hinckley refused to change the title and instructed members “to leave it alone.” However, at a different time, in a different political environment (China had become more open to the outside world), and with a boost from the Church’s name changing effort, Chia thought it might be the right time to give the Book of Mormon concern another try. A meeting was convened in Hong Kong on November 16–17, 2001. Fifteen people were in attendance, including two from Church headquarters (the director of the Asian translation department, who did not speak Chinese, and an English-Chinese translator who served a mission in Hong Kong), three from China (Chia Chu-jen being one of them), two from Hong Kong (one being a representative in the parliament and another a well-regarded surgeon), and eight from Taiwan (Casandra Tsai and Karl Liang were among them).

According to Chia, the English-Chinese translator from Church headquarters spoke first and proposed to not change the Book of Mormon title; the opinions then varied. Chia was worried about being outnumbered since there were only three people from China at the meeting. He addressed those in attendance before the meeting ended and asked the group to consider the potential impact of their decisions. He said that the current title might not have a strong impact on people in Hong Kong and Taiwan since the Church had been there for quite some time. However, it would affect millions of souls in China. He emotionally appealed to the group by painting a scenario of what Chinese people would say at the Final Judgment in front of Heavenly Father, blaming the negative connotations of Church and scripture names for their inability to accept the gospel. Chia told them that they would have to bear responsibility for those millions of people’s salvation.

The group dynamic and attitude appear to have shifted over the night. When the group reassembled the next day, a vote was taken on whether to change the title. They found themselves agreeing with each other, as no one opposed the change. The result led to the next question about what the new title should be. The group came up with many possibilities including one that caught many eyes: use 牧民 (mù mín) to replace 摩門 (mó mén). 牧 (mù) means “shepherd” or “to shepherd” and 民 (mín) means “people.” The phrase gives a “feed my sheep” image with a positive connotation that fits the Christian context well. The only problem the participants in the meeting had was that the phrase, although close, doesn’t sound exactly like “Mormon” in Mandarin, Cantonese, or Taiwanese.

Individual prayers were suggested to seek inspiration and spiritual guidance. Chia said he had his prayer answered two or three years prior to the meeting and the answer had not changed since. When the meeting resumed, Chia said many had tears in their eyes. The result was unanimous; all agreed to Chia’s idea to simply pronounce the “r” by adding the word “爾” (ěr) to the original phrase to make the title 摩爾門經 (mó ěr mén jīng).

No immediate official announcement was made regarding the Book of Mormon title change after the meeting. It was finally revealed when the retranslated triple combination was published six years later. In an August 22, 2007 letter signed by Presidents Hinckley and Monson, the First Presidency announced the newly translated scriptures. However, the letter did not mention the change of the title itself. The new title appeared quietly with the newly retranslated scriptures without fanfare or an explanation from the Church.

Sacrament prayers were also altered with the retranslated scriptures in both style and meaning. The new translation uses more vernacular wording than classical expression. By adopting the more common, everyday spoken language, the new prayers read as less poetic, rhyming, and elegant than the old ones. Literal translation is also more emphasized in the new prayers. One observation is the replacement of 上帝 (shàng dì) with 神啊 (shén a) for “Oh God” at the beginning of the prayers. Although both 上帝 and 神 mean “god,” the former tends to be more specifically used for the Christian god; the latter, on the other hand, refers to god in general. The latter seems also to fit better with the expression of 啊 (“oh”), which was not included in the original translation. Another notable change is the translation of the word “always.” The consistency of remembering Jesus Christ and of the Spirit’s accompaniment in the old prayers were more implied than overt through the use of the phrase 確常 (確 què, meaning “definite,” “certain,” or “indeed”; 常 cháng, meaning “frequent” or “often”). The new prayers leave no ambiguity in the expectation of Saints’ devotion through adopting the term 一直 (yī zhí, meaning “continuously” or “always”). This change actually addresses Chia’s concern outlined in his 1999 and 2000 letters to the Church translation department, in which he suggested “always” be used instead of “often” in the sacrament prayers.

Chia also pushed for other modifications of Church terminology, ten of which were formally announced on September 16, 2010, to either comply with common language usage in China or to be more aligned with their meanings in English.

Many of the new terms are Sinocentric, prioritizing political sensitivity and common usage in China over conventions in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. Take the translation of “clerk.” The old translation 書記 (shū jì, which literally means “bookkeeper” or “recorder”) was entirely accurate and adequate, except that it is specifically used to refer to the chief official of a branch of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Current Chinese president 習近平 (Xí Jìnpíng), for example, is also the General Secretary (總書記 zǒng shū jì) of the CCP. To avoid potential confusion in China, the title was changed to 文書 (wén shū), which is used more often for a document or Microsoft’s word processing software than a position. The term “General Authority” is very LDS-specific and a totally foreign concept to Chinese generally. There is no equivalent in Chinese; any translation, therefore, will inevitably sound awkward and distant. The original translation used six words to convey the idea: 總會當局人員 (zǒng huì dāng jú rén yuán), which indicates “people who are in charge of the general Church.” The word “authority” was not directly translated but certainly implied. To people in China, however, the translation might carry a political connotation, as the term 當局 (dāng jú) is conventionally used to refer to the Chinese government but not to other forms of authority. The new term utilizes eight words: 總會持有權柄人員 (zǒng huì chí yǒu quán bǐng rén yuán), which suggests “people who hold the authority in the general Church.” In this case, the word “authority” is literally translated and the political implication seems to be removed.

Table 1: Church Terminology Changes in Chinese Translation

|

Key Term |

Old Translation |

New Translation |

|

clerk |

書記 (shū jì) |

匡書 (wén shū) |

|

counselor |

릴會長 (fù huì zhǎng) 릴寮싱 (fù zhǔ jiào) |

諮잿 (zī lǐ) |

|

family history |

소譜 (jiā pǔ) 소磎歷袈 (jiā tíng lì shǐ) |

소譜 (jiā pǔ) |

|

genealogy |

소譜 (jiā pǔ) |

痢譜 (zú pǔ) |

|

General Authority |

總會當애훙員 (zǒng huì dāng jú rén yuán) |

總會넣唐權깨훙員 (zǒng huì chí yǒu quán bǐng rén yuán) |

|

member |

싱堂 (jiào yǒu) |

냥員 (chéng yuán) |

|

president (of a Young Women class) |

겯長 (bān zhǎng) |

會長 (huì zhǎng) |

|

Primary |

兒古會 (ér tóng huì) |

놓級겯 (chū jí bān) |

|

release |

菌출 (xiè miǎn) |

菌훨 (xiè rèn) |

|

Relief Society |

婦큽會 (fù nǚ huì) |

늣燎會 (cí zhù huì) |

Some new terms reflect more literal translations. For example, the Relief Society has been changed from 婦女會 (fù nǔ huì, meaning “women’s meeting/society”) to 慈助會 (cí zhù huì, meaning “compassionate service meeting/society”) and the Primary from 兒童會 (ér tóng huì, meaning “children’s meeting/society”) to 初級班 (chū jí bān, meaning “beginning-level class”). Many I talked to have the most problem with the change of Church membership from 教友 (jiào yǒu, literally meaning “Church friends”) to 成員 (chéng yuán, meaning “members”), because the new term removes connection, friendship, and intimacy; it conveys nothing more than a membership affiliation such as in a club or at Costco. To them, the new term seems aloof and unaffectionate.

In commenting on the adjustment to news names and terminologies, Chia suggests that the short-term unease (mainly for members in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau) is necessary when considering the long-term benefit for potential converts in China. He expects that current members will soon get used to the changes and incoming members will never know the difference.

New Brand Recognition

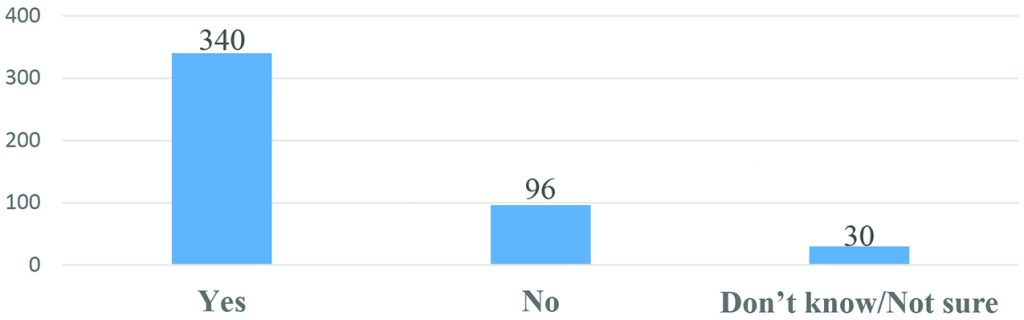

The second aspect of this research involves the fallout and implications of the new branding. How are the new names received by the public? Have they made a difference in missionary efforts? Do people outside of the Church use the new names or do they still associate the Church with the old? To understand the impact of the rollout of the name changes, I conducted an online survey in Taiwan in late 2018 and early 2019, targeting non-Latter-day Saints to explore the brand recognition of the Church. I utilized the snowball method to recruit respondents. In the survey, aside from demographic questions, I showed a picture of two male missionaries who carry an iconic representation of the Church and asked questions based on the picture. I received 475 responses; among them nine identified themselves as Latter-day Saints. I deleted those nine responses and focused on the remaining 466. The results showed a very low brand recognition overall, which indicates that the Church is mostly unknown to the general public in Taiwan.

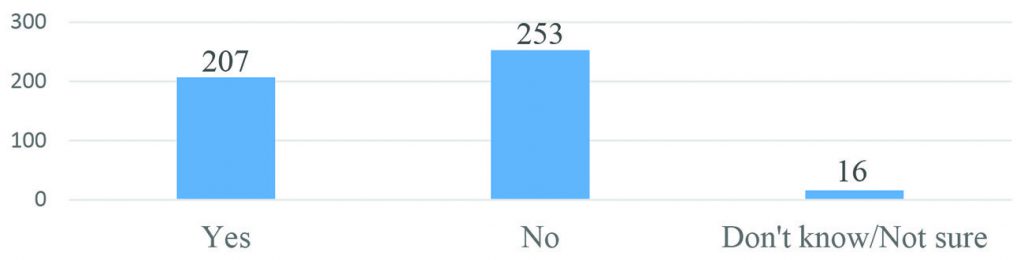

Figure 1 and figure 2 show that the majority (73%) of respondents recalled having seen missionaries; however, only less than half of respondents (44%) had actually talked to missionaries. When asked to identify the formal title of the Church from several choices, table 2 indicates that among the 466 respondents, only sixty-five (or 14%) were able to correctly identify the full name (either new or old) of the church that these missionaries belong to. This number does not include another eight who chose the “other” option and wrote down the nickname of the Church as the official name. Among those sixty-five people, only a bit over half (58%) recognized the new name. The vast majority of all respondents (74%) simply chose the “don’t know/not sure” answer.

Figure 1: Have Seen Missionaries Before

Figure 2: Have Talked to Missionaries Before

In comparison to the official name, table 3 shows that many people (38%) recognized the Church’s nickname, although the majority (62%) still had a hard time figuring which church this is. It is interesting to find that among those who knew the Church’s nickname, only seven recognized the new term 摩爾門教 (mó ěr mén jiào), while the overwhelming majority were more familiar with the old term 摩門教 (mó mén jiào). Of course, one can argue that the Church never officially changed its nickname; the name just came naturally with the title of the scripture.

Table 2: Official Church Name Recognition

|

Official name of the Church |

Frequency |

|

Don’t know/Not sure |

346 |

|

LDS (New) |

38 |

|

LDS (Old) |

27 |

|

Jehovah’s Witnesses |

13 |

|

True Jesus Church |

12 |

|

Baptists |

11 |

|

Presbyterian Church |

11 |

|

Other (Mormon Church) |

8 |

|

Total |

466 |

Table 3: Nickname Recognition

|

Nickname of the Church |

Frequency |

|

Don’t know/Not sure |

277 |

|

Mormon Church (Old) |

171 |

|

Presbyterian Church |

25 |

|

Baptists |

20 |

|

Moonies |

7 |

|

Mormon Church (New) |

7 |

|

American Church |

3 |

|

Unification Church |

2 |

|

Amish |

0 |

Table 4 is consistent with the general pattern found in the study. It suggests that the majority (75%) of those surveyed were unable to correctly identify the main scripture for the LDS Church. Comparing this result with table 3, one wonders why many more people were able to identify the Church’s nickname but unable to name the scripture the nickname is based on. Among the 117 who recognized the title of the book, only fourteen knew the new title 摩爾門經 (mó ěr mén jīng) without prompting.

Table 4: Major Scripture Recognition

|

Main scripture of this church |

Frequency |

|

Don’t know/Not sure |

284 |

|

Book of Mormon (Old) |

103 |

|

Heaven Lord God Doctrinea |

53 |

|

Book of Mormon (New) |

14 |

|

Koran |

7 |

|

Other (Bible) |

3 |

|

Book of Moonies |

2 |

|

Book of Zhuluob |

0 |

|

Total |

466 |

a. This is a made-up title: 天主神教約 (tiān zhǔ shén jiào yuē), a rough combination of Catholicism and the Chinese abbreviation of the Doctrine and Covenants.

b. Another made-up name: 珠羅經 (zhū luó jīng); it has a Buddhist-sounding tenor.

I asked respondents about their educational level and religious beliefs but did not find meaningful correlations between these two variables and their knowledge about the LDS Church. The survey results suggest at least two things: First, the Church is still very much on the margin of Taiwanese society. As mentioned earlier, LDS membership constitutes only 0.26% of Taiwan’s total population (one person in 386 is a member). The Church is not only small but almost entirely unknown there. People in Taiwan simply do not have much knowledge about the Church at all, even the most basic information. Second, the name changes seem to have had very little, if any, effect outside of the Church. Among those who know about the Church, only a handful of them are aware of the new titles, even a decade or two after the fact. The LDS Church has thus far failed to build its (re-)brand in Taiwan. I interviewed two former members of the Area Seventy, 梁世安 (Liáng Shìān a.k.a. Kent Liang) and 楊宗廷 (Yáng Zōngtíng a.k.a. Jared Yang), about advertising efforts after the name changes. Both of them maintained that there was no specific budget allocated for public relations purposes. Liang pointed out that one thing the local Church has been doing is establishing good relationships with government officials by meeting with some of them from time to time. He asserted that “the opinion leaders” would influence the public. While this two-step information flow can save time and money, it shows some passivity on the Church’s side. It seems to have proven ineffective thus far, perhaps because politicians have many other things to do and have no obligation to promote any particular religious group. Yang emphasized Church members’ personal responsibility to influence people around them. He suggested that members use social media and community activities to promote the Church. While this latter approach is more practical, a correlated effort is still lacking. Judging from the big budget the Church uses for public relations in the US and elsewhere (e.g., the multi-million-dollar “I’m a Mormon” campaign), some local members saw a missed opportunity for Church PR efforts in Taiwan, especially after the name changes.

Future Prospects in China

The main aim for both name changes and other terminology modifications was to help the LDS Church be acceptable in China. Yet even after the Church’s four decades of relationship building with the Chinese government and a decade or two after the name changes, the effects remain somewhat uncertain. To avoid political sensitivity, the Church withholds information regarding its development there. Pierre Vendassi, a French sociologist at the University of Bordeaux, estimated in 2014 that there were “several thousand practicing Mormons and congregations in every province.” Some Chinese members I talked to in 2019 think that the membership may have now reached ten thousand, with the bulk in major cities such as 瀋陽 (Shěnyáng), 北京 (Běijīng), 青島 (Qīngdǎo), 鄭州 (Zhèngzhōu), 上海 (Shànghǎi), 成都 (Chéngdū), 廣州 (Guǎngzhōu), and 中山 (Zhōngshān). The assessment by Matt Martinich, an independent demographer and project manager for the Cumorah Foundation, confirms the number and concentrations in an April 2020 Salt Lake Tribune article.

Two phenomena could, theoretically speaking, favor the Church’s potential in the Chinese market. In terms of the religious landscape, after decades of religious deprivation, people are hungry for a spiritual feast. China has experienced a religious surge since the 1980s. Official Chinese statistics count 100 million religion practitioners, but other estimates put the number between 350 million and one billion. The figure from the US State Department sat at 650 million in 2015. Non-traditional religions such as Christianity are swelling alongside traditional ones. One estimate shows Protestants at between 93 million and 115 million with Catholics between 10 million and 12 million. The field seems to be wide open for all. The cultural landscape may also put the LDS Church in an advantageous position among certain people because of its perceived Americanness. Many Chinese have a positive perception of the West, especially toward certain aspects of US culture. The Chinese saying that “the foreign moon is rounder” hints of foreign (Western) envy. Some imported products retain their original names in the Chinese market simply to sound foreign and exotic. A religion with an American brand can be an asset in some ways.

If the numbers reported by Vendassi, Chinese members I talked to, and Martinich are any guide, the growth of the LDS Church in China is rather minimal thus far in comparison to other religions. Three challenges the Church currently faces in China seem to run deeper than what name changes can cover. First is the burden of stereotypes. Even in a brand-new market, the faith still cannot escape from being seen as cult-like, as it is elsewhere. Abundant negative information online does not allow the religion to shake off its stereotypes and start anew, even with a new name. People are warned by their pastors or other Christians about the “heresy” Mormonism embraces before they have a strong grip on the belief system. A quick survey of “Mormon Church” on Baidu (百度), China’s main online search engine, yielded mostly negative information in the first five result pages. Aside from a few more neutral encyclopedia entries, most discussions center around whether the Church is a cult (an “evil religion”), its history with polygamy, and its non-Christian characteristics. Even tourism-themed websites often point out how mysterious, secret, and strange the religion is. Reviews of Mormon-related films such as A Mormon Maid and Mobsters and Mormons add to the effect.

Second, the Church’s Americanness is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, its foreignness and exoticism can attract attention and curiosity. Yet even in this case there is a problem: in reality the Church has not been able to take advantage of its Americanness. Since the Chinese government bans formal proselytizing, missionaries are not present in China. Without those young missionaries with white shirts, ties, and name tags—the icon of Americanness—visible on the streets around the country, the LDS Church seems less genuinely American and perhaps less appealing. However, on the other hand, a foreign (especially Western) religion carries imperialist baggage in China. Nineteenth-century Christian missionaries went to China with imperialist powers and weapons that sent the Middle Kingdom into a humiliating colonial condition. One of the strongest motivating ideologies within the PRC, from its origin until now, has been an effort to resist Western (especially US) imperialism. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao called Christians, among others, running dogs of Western imperialism (帝國主義走狗 dì guó zhǔ yì zǒu gǒu). This implied that they were lowlifes utilized to the imperialists’ ends. “Running dog” is often not attached to the phrase anymore, but animosity toward American imperialism and wariness of its cultural accompaniments persists. The US’s recent trade war with China and American accusations blaming the Chinese regime for the COVID-19 pandemic are among recent events that have led to stronger anti-American sentiment in China. A church with distinguishing American characteristics can still provoke much distrust.

The third and the biggest challenge is political. China is officially an atheist state under the Communist regime. The government has long held an antagonistic attitude toward religion, seeing it a threat competing for people’s loyalty and allegiance. It proclaims religious freedom, but spiritual activities are closely monitored. Faiths with an apocalyptic, end-days outlook, as mentioned earlier, are treated with deep suspicion, even though communism itself may be regarded as a type of millenarian utopia that hopes to build a socialist paradise. The Church’s name translation change may reduce the hurdle of immediate suspicion. However, it would be hard to remove or even disguise millenarian belief within Mormon theology.

According to the sociologist Fenggang Yang, religious organizations in contemporary China operate roughly in one of three markets: red, black, and gray. The five state-sanctioned “patriotic” religions—Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism—belong to the red market (the color of communism). Although legal, they are subject to strict regulation and expected to mingle patriotism into religious doctrines. The black market refers to the underground banned religions 邪教 (xié jiào, meaning “evil cults”), which face regular government crackdowns. The gray market includes anything in between, unregistered but tolerated spiritual practices. Technically, the LDS Church falls under the third category as it is still not registered, even twenty years after the name changes.

Chinese president Xi Jinping’s policy is moving toward a redefinition of the religious markets. Speaking at the 2016 National Religious Work Conference, he suggested that the Communist Party should take active measures

to guide religious believers to love the motherland and people, to safeguard the unity of China, to obey and serve the interests of the Chinese nation, to support the leadership of the CCP and the socialist system, and stick to the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics; promote Chinese culture and integrate beliefs with Chinese culture, and contribute to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

His talk has been interpreted as an attempt to close the gray market and force religions, especially foreign ones such as Christianity and Islam, to either join the red market under state control or go underground, becoming part of the black market with its attendant suppression. To survive, most Protestant denominations choose to comply, localizing their beliefs and practices under the three-self guidelines and developing a unique brand of “Christianity with Chinese characteristics.” Catholics in China, however, are more divided than Protestants due to Catholicism’s centralized structure and ties with the Vatican. Some choose red, working closely with the Chinese government; others resist in order to maintain doctrinal orthodoxy and loyalty to the Pope.

The LDS Church’s insistence on entering China through the front door is noble and respectable. Going in via the alley or the back door might have enabled the Church’s compatibility with other underground Christian denominations, but it would have damaged the trust with government officials. Being in the gray market, the Church has been able to grow, although not as rapidly as some other churches. Chia Chu-jen said that the Church in China thus far is in an ambiguous wink-and-nod situation. It is better for the Church to keep a low profile to avoid being seen by political leaders as a threat.

But what decision will the Church make if it is presented with the choice of going either red or black? Choosing red means that the Church in China will become an independent entity, cutting ties with the Church headquarters to avoid “foreign interference.” It also means that the Church there will need to not only comply with strict religious control but also likely teach Communist ideologies and become an indigenized “Mormonism with Chinese characteristics.” Choosing black means abandoning the good relationship the Church has made with the Chinese government and becoming one of the “evil cults.” I cannot imagine the Church in either of these scenarios. But how will the Church negotiate with the political establishment in China if Xi eliminates the gray market? The problem is more complicated than a simple name change can resolve. Nevertheless, the announcement of the Shanghai Temple during the April 2020 general conference, while not without obstacles, seems to point to the Church’s determination to have a presence in China for the long haul.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue