Articles/Essays – Volume 49, No. 4

Reassessing Joseph Smith Jr.’s Formal Education

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

How much formal schooling did Joseph Smith obtain in his youth and early adulthood? Such a question might appear innocuous, but it is fraught with implications that extend beyond a simple historical account of his educational opportunities. The amount of Smith’s formal education, or rather the various assumptions surrounding his presumed lack of it, has been enlisted by followers and detractors alike in order to frame Smith’s life within the narratives of divinely-inspired prophet or deceptive fraud, perhaps most acutely in the context of attacking or defending the origin and authenticity of the Book of Mormon.As Dennis Wright and Geoffrey Wright observe, “Ironically, both perspectives use the Prophet’s lack of formal education to strengthen their respective views.”Any attempt to isolate the amount of time Joseph may have actually spent in classrooms thus presents a challenge with deeper implications.

Furthermore, with the passage of time and the development of traditions, such representations become further entangled in cultural identities, transforming historical speculations into theological propositions that approach canonical certainties, interweaving Smith’s humble origins with the cosmologies of either faith or disbelief. These depictions, when further coupled with fragmentary historical records, complicate the process of excavating below the weighted representations in order to determine with any precision what might have actually occurred. Given such circumstances, this essay attempts to step back from the entangled layers of critical and apologetic modes to reexamine the historical sources and the assumptions underlying competing claims. By retracing the locations and educational practices of the places where Smith lived in his youth and early adulthood, this review will seek to demonstrate that Smith’s formal education was more extensive than passing speculations and shared cultural memory might suggest.

Before embarking on an analysis of Joseph’s life in relation to his formal educational opportunities (i.e., time spent in a formal school setting, as opposed to the various and common avenues of informal educational practices in early nineteenth-century America), I want to begin by exploring two important issues that will help to contextualize the interpretation of the incomplete array of historical references that address Joseph’s formal education: first, the role of education in the Smith family home, and second, an analysis of some of the more commonly known statements regarding Joseph’s limited education and abilities.

Smith Family Culture and the Role of Education

A review of Joseph Smith Jr.’s common school education necessarily begins with the importance of education within the Smith family home. Though this essay focuses on Joseph’s formal schooling, as opposed to domestic education and self-improvement, the role of family culture nevertheless constitutes the foundation of early nineteenth-century educational practices. For instance, that his father, Joseph Sr., had been a professional schoolteacher was certainly one of Joseph Jr.’s greatest advantages.So, too, was having a mother, Lucy, who had been raised in a household where her own mother, Lydia Mack, was also a school teacher.Indeed, Lydia may well have influenced Joseph Jr. directly. Lydia and Solomon Mack lived in Tunbridge, Vermont, where they were in constant close reach of their grandchildren, from the time of Joseph Jr.’s birth in 1805 to the Smith family’s move to Lebanon, New Hampshire, in either 1811 or 1812.

Education was deemed no less important on Joseph’s paternal side of the family. In April of 1799, Asael Smith, Joseph Jr.’s grandfather, who also lived in Tunbridge, Vermont, wrote a message to his entire family, admonishing them all to live good lives. In his treatise, Asael urged his family to educate their children: “Make it your chiefest work to bring them up in the ways of virtue, that they may be useful in their generations. Give them, if possible, a good education.”Asael’s message came two months after the birth of Alvin Smith, Joseph Jr.’s oldest brother, and may have been inspired by the new generation of grandchildren. Moreover, apart from parents and grandparents, older siblings got involved in the education of younger brothers and sisters.After his training at the prestigious Moor’s Charity School, Hyrum, Joseph’s second oldest brother, would have been expected to share in the education of his younger siblings. Indeed, Hyrum’s commitment to education would result in his becoming both a school trustee and schoolteacher in Palmyra.

This family concern for education thus created a dynamic where the parents and the older children were actively involved in the entire family’s instruction. Lucy would recall how she and her husband acted “together in the education and instruction of our children,”and John Stafford (1805–1904), a neighbor to the Smiths in Manchester, New York, remembered how the Smiths “had school in their house, and studied the Bible.”Ever since the colonial period, the task of teaching children how to read and write typically began at home, and the responsibility belonged chiefly to the mother.And even though Joseph Sr. had been a schoolteacher, the cultural expectation of raising educated, moral, upright children would have primarily fallen to Lucy. As education his torian Lawrence Cremin observes, “the new literature on child-rearing involved the vastly expanded responsibilities of the mother,” placing special emphasis on raising virtuous and principled citizens.Thus, having both a mother and a father actively involved in his education, young Joseph would have been exposed to greater instructional resources at home than most of his rural peers.

The Smith family’s emphasis on the importance of education provides a vital contextual framework for historical inquiry. Though sickness, relocation, and financial exigencies would constrain educational opportunities, Lucy and Joseph Sr. nevertheless engaged in a lifelong effort to provide their children with a solid foundation of instruction. The interpretation of historical accounts, particularly when confronting the lacunae in documentation, should therefore be mindful of Lucy and Joseph Sr.’s efforts and concerns. Interpretations that assume Joseph did not attend school whenever the historical documentation is silent runs counter to Joseph Sr. and Lucy Mack’s conscientiousness and stated efforts to provide their children with a good education. Thus, as a touchstone for the examination of educational practices, the cultural values within the Smith home offer guidance in the exploration of Joseph Jr.’s formal common school education, from youth to early adulthood, from Royalton, Vermont, to South Bainbridge, New York.

Representations

Furthermore, the survey of Joseph’s educational experiences requires an examination of the claims, often inconsistent and contradictory, made about his level of literacy. The majority of such statements, whether favorable or unfavorable, constitute retrospectives deeply informed by his eventual prophetic and miraculous accomplishments. The contextualization of assertions therefore requires the recognition that historical depictions of Joseph’s level of education rarely, if ever, present uncomplicated or unbiased accounts of Joseph’s life, delivered for no other purpose than the enrichment of posterity. Addressing every claim about Joseph’s education extends beyond the scope of this essay; nevertheless, in order to emphasize the need to interpret such state ments in their cultural context, I will look at two of the most common representational claims that are invoked as evidence of Joseph’s lack of education: Emma’s assertion that Joseph could not dictate a simple letter, much less a text the size of the Book of Mormon; and Joseph’s own statement that his education was limited to the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

In an 1879 interview, Emma Smith delivered her opinion on whether or not Joseph could have composed the Book of Mormon by famously declaring, “Joseph Smith . . . could neither write nor dictate a coherent and well-worded letter, let alone dictating a book like the Book of Mormon.”Emma’s statement, some forty years after the event, is often, and unfortunately, interpreted as a literal and objective depiction of Joseph’s writing and composition skills. Nonetheless, as his surviving letters, revelations, and journal entries well attest, Joseph could certainly write and dictate coherent letters and intricate texts.In order to appreciate Emma’s claim, we therefore need to reintroduce her comment to the cultural context in which it was given.

Emma’s juxtaposition of Joseph’s inability to write a “well-worded letter” with the production of a book of over five hundred printed pages reveals the assumptions she shared with her audience. Here, she is specifically invoking a parallel with introductory classroom exercises in nineteenth-century education: letter-writing was one of the earliest and most basic composition assignments children encountered at home and at school. By copying and composing short letters, children learned the style and format of basic correspondence, along with the skill of assembling cohesive paragraphs. For instance, one of the most popular letter-writing schoolbooks of the early nineteenth century was Caleb Bingham’s Juvenile Letters (1803), which consists entirely of short, easy to-read letters written by fictional children “from eight to fifteen years of age.”Thus, Emma’s depiction of Joseph’s writing ability presents two polar extremes: the expansive Book of Mormon text pitted against a simple “well-worded letter.” In other words, in order to emphasize her opinion that Joseph could not have produced the Book of Mormon, Emma declared that Joseph could not compose at the level of a child receiving his first writing lessons in one of the most elementary forms of composition exercises. Emma’s hyperbolic statement should be read with the same tone as, “he couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time,” or more specifically, “he couldn’t compose at the level of Dick and Jane, much less write a whole book.” Yet, in spite of this dismissive characterization, Emma’s facetious exaggeration need not be interpreted as an intentional misrepresentation. Her comment merely serves to highlight her emphatic belief that Joseph could not have created the work without divine assistance.Thus, while Emma’s comment provides insight into her beliefs and sense of humor, a literal interpretation of her assertion obscures Joseph’s actual compositional skills.

Joseph’s self-representation of his educational opportunities appears in what Dan Vogel describes as “the earliest known attempt by Joseph Smith to record a history of his life.”Dictated in 1832, the statement reveals how the indigent circumstances of the Smith household “required the exertions of all that were able to render any assistance for the support of the family; therefore, we were deprived of the benefit of an education. Suffice it to say, I was merely instructed in reading, writing and the ground rules of arithmetic, which constituted my whole literary acquirements.”While this depiction may initially appear straightforward, several issues require a cautious interpretation of what precisely this statement means. I do not want to minimize the essential claim being made regarding Joseph’s childhood opportunities. As this essay hopes to demonstrate, his chances to participate in formal education were limited and intermittent, with few chances to complete a full year of school without significant interruptions. Nevertheless, if we interpret “deprived of the benefit of an education” to mean “entirely denied an education,” then Joseph’s statement contradicts itself (i.e., if completely deprived, Joseph would not have learned basic reading, writing, and arithmetic skills). Thus, the statement requires further contextualization.

Joseph’s description of “reading, writing and the ground rules of arithmetic” invokes a common, formulaic phrase in early nineteenth-century America (indeed, it remains common today, often expressed as “the three R’s”), which operates as a shorthand depiction of the most basic, fundamental level of education that early Americans hoped to achieve in an education system. Gideon Hawley, the first New York Superintendent of Common Schools, invoked this formula in the process of working toward a standardized curriculum in his 1819 publication, Instructions for the Better Government and Organization of Common Schools, in which he writes, “in every common school the course of study to be pursued must necessarily embrace reading, writing and arithmetic. These are the first rudiments of education. . . . Reading, writing and arithmetic, as they are the means of acquiring all subsequent knowledge, may justly be considered the necessaries of education. . . . Nothing short of these will constitute a common school, or satisfy the lowest requisites of the school act.”The phrase, however, does not provide a detailed account of the actual training and material children encountered in classrooms.

In the process of learning how to read, children studied grammar, the basics of rhetoric and composition, geography, short passages on history, and other potential subjects (depending on the skills and interests of the instructor). We also know from various historical accounts that Joseph owned several common school textbooks that were published and available during his school years, such as Lindley Murray’s English Reader (1799), Charles A. Goodrich’s A History of the United States of America (1822), and Thomas T. Smiley’s Sacred Geography (1824).Thus, Joseph’s description of “reading, writing, and arithmetic” elides a rich variety of topics and exercises that actually occurred in classrooms. Joseph’s enlistment of this formulaic phrase therefore functions as a rhetorical device to convey his limited educational opportunities to his readers, without going into the unnecessary detail of outlining every topic, every skill, or every assignment he encountered. Put another way, the rhetorical effect of Joseph’s depiction would have been defeated, obviously, if he had said, “I was merely instructed in reading, writing, arithmetic, basic rhetoric, composition, geography, and history,” though such a catalogue would have more accurately depicted the curriculum he would have encountered in common school classrooms.

Joseph’s representation of his educational achievements requires further recognition of how this depiction functions within the context of his entire narrative. Joseph’s 1832 history was not an indifferent account of his life. Rather, the account represents his first attempt to construct a narrative that centers on his divine prophetic calling. As Vogel aptly observes, “The History was begun in the midst of challenges to Smith’s authority, primarily initiated by Bishop Edward Partridge in Missouri, which evoked Smith’s introduction of the office of president of the high priesthood. It is therefore not simply an autobiographical sketch, but an apology setting forth Smith’s credentials as leader of the church.”As part of this project, Joseph’s reference to his humble beginnings, contrasted with his rise to prominence as God’s chosen instrument, evokes the commonplace trope of the humble individual who, against all odds, rises to greatness—a popular framework of biographical representations in both secular and religious maelstroms of early nineteenth-century America.Thus, the formula of “reading, writing, and arithmetic,” as a representation of the bare minimum level of education one might receive, acts as a counterpoint to the lofty heights to which God would come to elevate Joseph’s life and work. Nevertheless, setting such rhetorical effects aside, we do not receive a detailed account of Smith’s educational experiences, and are left to wonder about the actual time he spent in school and the lessons he learned. By retracing his life and experiences, this essay therefore aims to further the discussion surrounding Joseph’s background, education, and training.

Royalton, Vermont: 1809 to 1811/1812

Junius F. Wells, a member of the Mormon Church who purchased the farm where Joseph had been born, provides the first reference to Joseph’s earliest formal education. When describing the Smith’s family life in rural Vermont, Wells indicates that “during this period, Joseph, Senior, worked on the farm summers, and taught school part of the time winters. His son Joseph attended the school on Dewey Hill, and was taught his letters by Dea[con] Jonathan Kinney, the schoolmaster there.”Joseph Jr. was born in Sharon, Vermont, on December 23, 1805. Sometime between the months of March and December in 1808, the Smiths, who had been moving among several locations in the region, relocated to Royalton, Vermont, where they lived for approximately three to four years.The exact length of their stay is uncertain. According to Lucy’s account, the Smith family moved out of the area in 1811; according to tax assessment records, however, the move did not occur until sometime between May 1812 and May 1813.In either case, Joseph Jr. would have grown from a three-year-old toddler to a five- or six-year-old child in Royalton, Vermont, prior to the family’s relocation.

During that time in Vermont, it was typical for children to start school at the age of four. Ever since the General Assembly of the State of Vermont passed the Act for the Support of Schools in October of 1797, determinations regarding the formation of schools, allocation of funding, and selection of trustees in any given district were made “according to the number of children in such district between the age of four years and eighteen years old.”These ages were based on the customary ages of children attending school throughout the state, but they were not the exclusive ages of those who actually attended classes. In any given district, children might start school earlier than four or attend later than eighteen. Indeed, children throughout New England were known to start school as young as two or three years of age.Nevertheless, in order to have a common standard of funding for all the counties, the state used the census figures and school records to identify the population that customarily attended school and allocated funds accordingly.

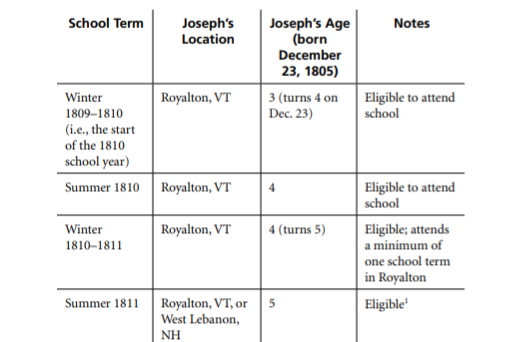

That children four years of age, and even younger, were attending common schools was not unusual.Throughout the United States in the earliest decades of the nineteenth century, the average starting age for school children ranged from four to five years.And though the determination of such ages may have been arbitrary in each state, they often reflected the circumstances of the population, particularly in farm ing communities. In rural schools, according to historian Carl Kaestle, children “began at younger ages and enrolled in greater proportions than their urban contemporaries. By the age of four or five, and until the age of about fourteen, most rural children in the North . . . attended school at some time during the year.”Kaestle further suggests that “parents who sent very young children to school seem to have done so through a desire to have them out from under foot. . . . One can understand the desire of rural mothers with busy work schedules to be freed from the care of toddlers.”Thus, basing estimates on the customary ages of school attendance in Royalton, the following scenarios emerge: if the Smiths moved out of town in 1811, as Lucy suggests, Joseph would have been able to attend school for three, possibly four, terms (winter 1809–1810, summer 1810, winter 1810–1811, and summer 1811); if the Smiths moved in 1812, as tax assessment records indicate, Joseph would have been able to attend five terms (the terms noted above, along with winter 1811–1812). Accordingly, if he started school at the same age as his Royalton peers, Joseph could have received either one and a half or two and a half years of formal schooling, depending on the date of the Smith family’s departure. The point is significant: prior to Joseph’s departure from Royalton, he may well have obtained as much formal education as historians tend to attribute to his entire lifetime, if not more.

West Lebanon, New Hampshire: 1811/1812 to 1814/1815

Lucy Smith provides the next reference to her children’s formal schooling in her history, Biographical Sketches (1853). In 1811, according to Lucy, the Smith family relocated approximately twenty-three miles southeast of Royalton, across the Connecticut River, to the town of West Lebanon, New Hampshire. About the same time, Hyrum began attending Moor’s Charity School, originally called Moor’s Indian Charity School, which was located on the same campus as Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, approximately seven miles north of the Smith’s new home in West Lebanon.Though Moor’s Charity School was technically a separate institution from Dartmouth at the time, the distinction was largely in name only.Hyrum’s acceptance would have held the hope of a promising career, and upon the Smith family’s arrival in West Lebanon, Lucy indicates that “as our children had, in a great measure, been debarred from the privilege of schools, we began to make every arrangement to attend to this important duty. We established our second son Hyrum in an academy at Hanover; and the rest, that were of sufficient age, we were sending to a common school that was quite convenient.”(It should be noted that Lucy’s recollection here has minimal bearing on Joseph’s education: her statement refers to challenges that occurred previously in Vermont, where Joseph had only recently started school.) Because Lucy did not specifically name the children who “were of sufficient age” to start school in West Lebanon, some historians have assumed Joseph Jr. did not attend school at this time.Nevertheless, children in New Hampshire started school at the same ages children started in Vermont.

Unlike Vermont and New York during this period, New Hampshire based school funding on overall population, rather than census numbers and school records for children within a particular age range.As such, the state did not provide information in its laws reflecting the customary age for children to start school. Even so, memoirists and observers indicate that children in the state began school as early as two to three years of age.During his tours through New England and New York from 1795 to 1816, Timothy Dwight, IV (1752–1817), President of Yale College, observed, “In Massachusetts, New-Hampshire, and Vermont, schools are everywhere established. They are often styled parochial schools. . . . To these little seminaries the children of New-England are universally sent, from two, three, four, and five years of age, to the period in which they have learned to read, write, and keep accounts. . . . I speak of the common schools only.”Within this context, the year the Smith family moved to West Lebanon becomes irrelevant with respect to schooling: Joseph Jr., who turned six in December of 1811 and seven in December of 1812, would have been old enough—indeed, much older—than

children “of sufficient age” to start school in New Hampshire.The winter of 1812–1813 would, however, bring a traumatic interruption to young Joseph Jr.’s formal education. Whether or not he started school that winter term, he certainly would not have finished it. During the winter, a typhoid epidemic “swept through the upper Connecticut Valley and left 6,400 dead in five months.”Young Joseph was not spared the fever. The story is well-known: the infection spread through his body, eventually locating in his lower left leg and causing a bone infection. The Smiths summoned medical doctors from Dartmouth and the decision was eventually made to cut the infected bone from Joseph’s leg. Though the operation was successful, Joseph would have been bedridden for the next several months, waiting for the wound to heal.

Joseph’s experience would, of course, affect his formal schooling. His attendance during the winter term of 1812–1813 would have been abruptly cut short by his infection and surgery. He almost certainly missed the 1813 summer term as well, not only because of convalescing at home, but due to a possible trip to Salem, Massachusetts, with his Uncle Jesse. “When he had so far recovered as to be able to travel,” Lucy recorded, Joseph Jr. “went with his uncle, Jesse Smith, to Salem, for the benefit of his health, hoping the sea-breezes would be of service to him.”Thus, for the 1813 school year, Joseph’s educational improvement would have been limited to reading books, family devotionals, and domestic education.

Lucy’s history suggests Joseph returned to formal schooling in the winter of 1813–1814, after approximately a full year of recuperation. Immediately following her account of Joseph’s surgery, Lucy indicates that, “Having passed through about a year of sickness and distress, health again returned to our family” (her 1845 manuscript reads, “After one whole year of affliction we were able once more to look upon our children and each other in health”).Young Joseph, though continuing to convalesce and recover, was apparently no longer bedridden. Thus, from the time of his return until the Smith family’s move to New York, Joseph may have experienced one of the longest periods of sustained formal education in his lifetime: because he would remain on crutches until the Smith family’s move to New York, Joseph would have been prevented from performing heavy farm labor for the remainder of the family’s stay in the Connecticut Valley, allowing him full participation at school in both winter and summer months.In such a compromised physical condition, school attendance, reading, meditation, and domestic chores would have been the extent of his activities.

Norwich, Vermont: 1814–1815 to the Winter of 1816–1817

Sometime between May of 1814 and March of 1816, the Smith family moved back across the Connecticut River to Norwich, Vermont, situated approximately two miles west of Dartmouth. The exact time of their arrival is yet again uncertain.Furthermore, records are silent regarding the Smith children’s school attendance, though Wright and Wright observe, “When considering this period in Joseph’s life, it seems consistent to assume that his mother would have again encouraged him and his siblings to attend public school.”During their stay in Norwich, the family was plagued with a series of crop failures, which left the family destitute.After hearing about cheap land and better farming conditions in western New York, no doubt combined with rumors of the economic potential of the region, Joseph Sr. decided to relocate the family to Palmyra, New York, a town that would become a stop along the Erie Canal. In late 1816, Joseph Sr. went to Palmyra by himself to make arrangements, while the family packed their belongings and followed after him, apparently in January of 1817.

Thus, in terms of formal schooling opportunities, the timing of the Smith family’s departure provides a window for their stay in the Upper Connecticut River Valley. From the time the family arrived in West Lebanon, New Hampshire, in 1811 or 1812 to their final departure from the area in the winter of 1816–1817, Joseph Jr. would have been eligible to attend school for either five or six terms (winter 1811–1812, summer 1812, then skipping the 1813 school year, followed by winter 1813–1814, summer 1814, winter 1814–1815 and summer 1815). Depending again on arrival and departure dates, the amount of eligible formal education for this period would be between two to three school years.

Palmyra, New York: 1817 to 1820/1821

The Smith family’s move to Palmyra, a journey of about three hundred miles, would have taken approximately one month.The move would occur in the middle of the 1816–1817 winter term, effectively disrupting the start of the school year, though one account suggests the children attended the latter part of that term after initially getting settled in western New York State. Jacob E. Terry of East Palmyra was one of Joseph’s classmates. Vogel observes that if Jacob’s sister, Elizabeth, is correct in her memory of the dates and locations where their family lived, as recorded in the Parshall Terry Family History (1956), then “this would indicate that Joseph Smith attended school immediately after his arrival at Palmyra sometime during the winter of 1816–1817.”Such partial attendance would not be the last time the children’s formal education would be interrupted, particularly because of financial exigencies. Upon their arrival, Lucy records how the Smith’s held a family council regarding their “destitute circumstances” and how they “came to the conclusion to unite our strength in endeavouring to obtain a piece of land.”This being the case, the children old enough to work likely spent their summers earning money to help the family, rather than attending school during the summer terms. Thus, though he had only recently stopped walking with crutches, Joseph probably started working in the summer of 1817. And given the continued financial struggles of the Smith family, Joseph may never have attended another summer term at any common school again.

Insight into the Smith family’s financial challenges, particularly in relation to formal education, emerged with the 2008 discovery of Phi lander Packard’s school records.Packard, a school teacher in Palmyra’s District No. 1 (the same district in which the Smith family lived), kept a record of tuition payments he received from his students.Instead of entering the child’s name, however, Packard listed funds received under the heads of households. “Joseph Smith” appears among them, nestled in a list that includes several of the Smith family’s neighbors.And as Donald L. Enders observes, the payments from the Joseph Smith family were the second lowest in the account book, bested in meagerness only by the widow Hannah Hurlbut and her child.The document provides stark evidence of impoverished family circumstances. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize that Packard’s notes are not attendance records but running accounts of payments. Interpreting the documents as attendance records for poor families is, in fact, highly problematic. Thus, contextualizing Packard’s records within New York’s common school system is crucial.

Before the Smith family moved to Palmyra, Gideon Hawley, Superintendent of Common Schools for the State of New York, had been mounting an aggressive campaign to provide a common school education to all the children in the state. Since 1812, when New York instituted a statewide common school system, universal access to education had become a social and political priority; and Hawley recognized that children from poor families often could not afford to pay their share of teachers’ wages and therefore could not regularly attend school. Hawley thus participated in shaping new laws for the common schools, explicitly giving local school commissioners the power to waive tuition costs for poor families. Encouraged by Hawley’s advocacy, the legislature passed The Act for the Better Establishment of Common Schools on April 15, 1814, which allowed commissioners and local trustees “to exonerate from the payment of the wages of such teachers, or the residue aforesaid [balance of wages not paid by the state], of such wages, all such poor persons within their district, as they shall think proper.”Hawley’s strategy proved to be an enormous success. Between the state funding and the waiver of local fees, children from poor families gained access to the same educational opportunities as all other common school students, and overall statewide attendance began to rise significantly in each successive year. In his report to the legislature for the 1819–1820 school year, Hawley reveled in the progress of the common school system:

There is now therefore, reason to believe that the number of children in the state who do not attend any school, and who are not otherwise in the way of receiving a common education, is very small. The public bounty is sufficient to defray the expense of most schools for about three months in the year; and where that is expended in different parts of the year, so as not to defray the whole expense of the school for any particular part, it is understood that in most districts, poor children have been permitted to attend the district school free of expense, under that provision in the [1814] school act which empowers districts to exonerate such children from the payment of teachers’ wages.

As Hawley’s presentation indicates, payment for common school education came from both public and private sources: state funding covered a portion of the year (“about three months”), while local taxes and assessments made up the difference for teachers’ wages. If the local commissioner and trustees deemed a family too poor to pay an assessment (in full or in part), the children would be entitled to attend school either free of charge or at a reduced rate, in accordance with the family’s ability to pay. Thus, Packard’s school records reveal the families who could afford to pay, along with the families who apparently could not. But the point needs to be reemphasized that the accounts do not indicate actual attendance at school. Indeed, rather than providing evidence of the Smith children’s lack of attendance, Packard’s school record very likely suggests the opposite. Because the “Joseph Smith” family was one of the poorest in the records, they would have been among the most eligible candidates for tuition waivers. And if they did in fact receive full or partial waivers, the Smith children could have been in regular attendance at classes, even though Packard’s accounts would show a near absence of payments. The widow Hannah Hurlbut’s child, for example, though the least able to pay, with empty column after column of payments received, would nevertheless be entitled to, and may well have been participating in, full and regular attendance over the duration of Packard’s accounts. Thus, while Packard’s records potentially reveal the indigent circumstances of the Smith family, they nevertheless do not confirm the actual attendance or non-attendance of the Smith children at school.

The unreliability of Packard’s records as attendance records is further complicated by the time period they cover. As Enders astutely observes, Packard’s notes cover only the period from September 9 through October 7, 1817, while “the columns are blank after Friday, October 10, possibly because it was harvest time, even though the headings continue through Saturday, November 1.”The point is significant: planting and harvest times were the two busiest periods in the life of a farming family. And in the first decades of the nineteenth century, when frontier towns rapidly grew in size and started to become well established, school years often lengthened from shorter periods (roughly five months) to longer sessions (seven to eight months). Such changes resulted in schools commencing winter terms during the fall harvest season. For a poor family like the Smiths, who could not afford to hire additional laborers, the oldest children would likely have stayed home to work on the farm, delaying attendance until after the harvest. Thus, Packard’s records are silent on the Smith children’s status in the post-harvest winter months. Nevertheless, the records, even if indirectly, offer potential insights into the working and educational lives of the Smith children.

Harvest season did not occur at precisely the same time each year, because of weather conditions and the annual variations for the maturation of crops. Nonetheless, the harvest season in upstate New York for sweet and silage corn, barley, beans, oats, potatoes, and wheat usually finished by the end of October. The exceptions were field corn (dried and hardened, usually for animal feed) and possibly soybeans (an uncommon crop in upstate New York, used for animal feed in this period), which usually occurred by the end of November.In terms of scheduling the actual harvest, farmers relied heavily on weather predictions in the yearly almanacs. In 1817, for example (the fall season in which Packard kept his school records), almanacs covering New York, Pennsylvania, and the surrounding states (mostly New England) consistently urged readers to prepare for winter in late November with the anticipation of snow and storms in early December.Whether or not inclement weather actually occurred, farmers would nevertheless have worked to finish harvest before those dates.

Thus, if he were working on the family farm or hiring out to neighbors for the 1817 harvest, Joseph Jr. would likely have delayed attendance at school until the end of October at the soonest, or the end of November at the latest. Planting season for the following year would not begin until late March at the earliest (usually early April), which would result in Joseph attending approximately only four to five months each school year in Palmyra and later in Manchester. This estimate finds indirect support from Lemuel Durfee’s account book for 1815–1829. After Durfee purchased the Smith family farm on December 20, 1825, the Smiths continued to work the property, while Samuel Harrison Smith (Joseph’s younger brother) worked for Durfee to pay the rent on the farm. Durfee’s account reads, “April, the 16 day, the year 1827, S. Harrison Smith, Son of Joseph Smith, began to work for me by the month. Is to work 7 months for the use of the place where said Joseph Smith lives.”This “7 months” span, from April to November, coincides with the regular farming season, from planting to harvest. This then sug gests that the Smith children who hired out their labor were working the same yearly schedule as their adult contemporaries, causing them to delay their attendance at school each year.

While the precise details of his school attendance in Palmyra are elusive, Joseph Jr. still managed to appear at school. Several of his former classmates mentioned attending with him during the family’s years in Palmyra. William H. Cuyler, a lifelong resident of Palmyra, “attended school with Joseph Smith the Mormon, and his brothers—particularly Alvin [1798–1823] and William [1811–1893].”Isaac Butts also “attended school with Prophet Jo” in Palmyra.And Jacob E. Terry of East Palmyra was said to be “a school associate and friend of young Joseph Smith, they being the same age.”The Smith family would remain taxpaying residents in the Palmyra school districts from 1817 to late 1820 or early 1821, but they were not planning to stay in town indefinitely.

Between April 1819 and April 1820, some of the members of the Smith family moved “into a small log cabin on the property of Samuel Jennings on Stafford Road near the southern border of Palmyra township.”This cabin was adjacent to a parcel of land they hoped to purchase for a family farm in the neighboring town of Manchester. Though they did not yet own the land, the Smiths were apparently confident enough of its purchase to start developing the property. For approximately two to three years, the Smiths maintained residences on both Main Street and Stafford Road in Palmyra; and the cabin appears to have served initially as an outpost, where family members stayed who were developing the Manchester land.The Smiths would eventually take formal possession of the Manchester property sometime between July 1820 and February 1821.This period therefore marks the time when the Smith family became official residents of Manchester.Whether or not the children started attending school in Manchester at this time, however, is not known.

As of April 1822, the Smiths were still recorded on the Palmyra road list, suggesting that the family had not yet made a full transition to the Manchester farm.Therefore, the children apparently could have attended school in either Palmyra or Manchester during the 1820–1821 winter term. These dates provide a framework for Joseph’s potential attendance at school in Palmyra. If he started school in Manchester during the same period in which the Smiths took possession of the new farm (1820–1821), then Joseph Jr. would have been eligible to attend three winter terms in Palmyra (winter 1817–1818, winter 1818–1819 and winter 1819–1820). If, however, he continued to attend school in Palmyra after the Smiths officially purchased the Manchester property (this would assume he traveled back and forth the relatively short distance between Manchester and Palmyra), then Joseph would have been eligible to attend five winter terms in Palmyra (winter 1820–1821 and winter 1821–1822, in addition to the above mentioned).

Manchester, New York: 1820/1821 to 1825

At this stage, Joseph’s age becomes a factor for consideration. Less than three months after the beginning of the 1820–1821 winter term, Joseph turned fifteen years old. According to the New York Act for the Support of Common Schools, passed the previous year in 1819, the local commissioners of common schools distributed state funds “according and in proportion to the number of children, between the ages of five and fifteen years, inclusive, living in each such [school] district.”The age range, though arbitrary, nevertheless reflects cultural assumptions about the normative age range of common school students in New York. Therefore, because he turned fifteen on December 23, 1820, Joseph could have dropped out of school at that time, without disrupting social conventions or doing anything unusual in comparison to his peers. Yet, in spite of this option, Joseph nonetheless attended at least one term in Manchester, as attested by Joseph’s former classmates in the township.

contracted for their new farm sometime between July of 1820 and February of 1821; thus, they would not have begun paying taxes or school assessments to Manchester Township until that time (EMD 5:391–392). In order for the Smith children to attend school in Manchester prior to that time, Joseph Sr. and Lucy would have been required to get permission from the trustees of both Palmyra’s and Manchester’s school districts (see EMD 3:258n4, where Vogel indicates, “according to early maps of Manchester, the Smiths’ former residence was included in school district 11”). Permissions for families to trans fer children from one school district to another (within a township or across township lines) took place during town meetings. Palmyra’s minutes in 1815, for example, indicate how “Enoch Saunders is set off from 1st School District in Palmyra with leave to annex himself to Farmington. Parshall Terry is set off from Palmyra with leave to attach himself to Farmington. Isaac Sweezy is set off from Palmyra with leave to attach himself to Williamson. Martin Harris [Joseph’s early supporter] is set off from School District No. 1 and attached to School District No. 8 in Palmyra.” None of the town minutes record the Smith family transferring their children from a Palmyra school district to a Farmington/Manchester district, which strongly suggests the Smith children attended school in Palmyra until the family became taxpaying residents of Manchester between July 1820 and February 1821 (when they could transfer schools without needing permission or being recorded in the town minutes). See Town of Palmyra, “Town of Palmyra Board Meeting Minutes,” Palmyra, N.Y.: Town & Village of Palmyra, 1815, http://www.palmyrany.com/minutes/ TB/1815.pdf. While the Manchester trustees could have allowed the Smith children to attend their school, the Smiths normally would have been required to cover all the costs of their children’s attendance. The 1822 revision of the common school act of New York indicates, “But if children, not residing in the district, be permitted, by the trustees, to attend their school, as such permission might have been withheld, it may, and ought, if granted, to be on condition that no part of the public money shall be applied for their benefit” (The State of New York, The Act for the Support of Common Schools: 35 [emphasis added]). The Smiths were struggling financially at this time, suggesting the children would have continued to attend school in Palmyra, where they would not incur additional expenses. An exception to this rule would be the case in which neighboring townships shared a school district. Nevertheless, Manchester school district 11 was not a jointly-shared school district with Palmyra. The only school district the two towns shared at this time was Palmyra’s District 21, formed on February 14, 1820, which contained Palmyra lots 46, 50, 53, and part of 37 in Township 12, 2nd range, joined together with Manchester Orrin Porter Rockwell, a well-known Mormon convert and longtime confidant of Joseph’s, “was a schoolmate and friend of Smith’s” in Manchester.Moses C. Smith, another Manchester classmate (not related to Joseph), was said to have “attended [school] with the Prophet and once they had an altercation.”And Samantha Payne, also of Manchester, claimed to have “attended school with [Joseph] for some time.”Thus, if he started attending school in Manchester during the first term in which he was eligible as a resident, Joseph would have attended at least the winter 1820–1821 term.

A subsequent question then naturally arises: did Joseph stop attending school in Manchester after the 1820–1821 winter term or did he continue to participate longer? Again, historical documentation does not provide a clear answer. Nevertheless, a look at the laws governing school funding, coupled with the state’s statistics on school attendance, offers further insight and clarification. To begin, in order to determine how much money the state would allocate to each school district, New York’s Act for the Support of Common Schools in 1819 measured the population of all the children “between the ages of five and fifteen years” within every county, regardless of actual attendance. Legislators then used this overall population to determine the amount of money each county would receive. It is important to note, however, that this law did not restrict school attendance to children between those ages of five and fifteen; the figures merely provided guidance for funding allocations.Thus, students could attend school at any age. The 1822 clarification of the 1819 Act states, “In applying the public money, it must always be paid to the teacher on account of his wages. It is not to be distributed among the scholars or their parents; nor is it to be applied for the exclusive benefit of children between the ages of five and fifteen years, or of any other particular description of scholars. All who reside in the district and attend the school, as they may of common right, must necessarily participate equally in the benefit of the public money.”As such, Joseph could have continued attending common schools for the remainder of his teenage years in Manchester, if he so chose. And whether or not he took advantage of this opportunity, many of his peers did.

According to the annual reports of the New York Superintendent of Common Schools, students throughout the state frequently attended classes at ages younger than five and older than fifteen years. And this was certainly true for Manchester. In the 1821 school year (when Joseph turned sixteen), Manchester taught a combined total of 1,051 students. Of these students, 972 were five to fifteen years of age, leaving a remainder of seventy-nine students either younger than five or older than fifteen (7.5 percent of all students).And the pattern continued for all the years the Smith family resided in Manchester: in the 1822 school year, seventy-four students younger than five or older than fifteen attended (6 percent of the total 1,236 students taught);in 1823, sixty students younger than five or older than fifteen attended (7.8 percent of the total 770 taught);in 1824, eighty-three students younger than five or older than fifteen attended (9.8 percent of the total 850 taught);and in 1825, the number of students younger than five or older than fifteen jumped to 179 (18.2 percent of the 985 taught, or nearly one in five students).

Joseph’s continued presence in school and desire for an education are suggested not only by the presence of other older students in Manchester, but by additional clues. During this same period, for example, Joseph attended a juvenile debating society, likely during the 1821–1822 winter when he turned sixteen, which reveals an ongoing and self-motivated desire to improve himself.Tantalizing clues also emerge from his personal library. For example, Joseph owned the Reverend Charles A. Goodrich’s schoolbook A History of the United States (1822), an advanced school reader that Joseph donated to the Nauvoo Library and Literary Institute on January 31, 1844.First published sometime after March 8, 1822, Goodrich’s History quickly became popular in common schools and was “reprinted forty times in just ten years; eventually his work sold over 150,000 copies during the decade of the 1840s.”Nevertheless, rather than encountering this popular text in school, Joseph likely used this schoolbook in one of the several avenues of self-improvement he pursued, such as domestic education or participation with the juvenile debate society.

More directly linked to classroom study, Joseph’s copy of Murray’s English Reader (1799) suggests Joseph’s impressive level of common school achievement. Murray’s Reader was one of the most advanced textbooks that youths encountered in common schools.Only the oldest and most experienced common school students studied from this text, which required a prerequisite sequence of schoolbooks that included primers, spellers, grammars, and other introductory readers. Thus, Murray’s Reader not only reveals Joseph’s abilities, it also signals the extensive history of educational development needed in order to acquire the skills necessary to use this book. Joseph’s participation in a juvenile debate club and his ownership of Murray’s Reader and Goodrich’s His tory therefore provide clues which suggest that Joseph continued—even if only intermittently—to attend school in Manchester during his later teenage years.In any event, Smith’s formal education in Manchester would have ranged from a minimum of one winter term (1820–1821) to a maximum of five winter terms (1820–1825).

South Bainbridge, New York: 1825 to 1826

The final location in this review of Joseph’s formal education is South Bainbridge, New York. In October of 1825, Josiah Stowell hired Joseph Jr. to work as a scryer for a team of treasure hunters. A few months later, Joseph was arrested and stood trial in Bainbridge on March 20, 1826, accused of being a “disorderly person and an Impostor.”According to court documents, Joseph admitted to working for Stowell as a treasure-hunting seer, but asserted that the majority of his time was spent working on Stowell’s farm “and going to school.”Stowell’s son, Josiah Jr., corroborated the court record in an 1843 letter, in which he claimed, “I have been intimately acquainted with him [Joseph Smith Jr.]. He then was about 20 years old or there about. I also went to school with him one winter.”Another student, Asa B. Searles, also claimed to have attended school with Smith in Bainbridge.

When he started school with Josiah Jr., Joseph was nineteen years old and would turn twenty in the course of the winter term. From a modern perspective, Joseph’s advanced age for such instruction might seem awkward, but no doubt his history of intermittent attendance contributed to his desire to participate. The circumstances surrounding his attendance, however, urge caution against the exclusive assumption that Joseph’s attendance derived from a desire to fill any potential gaps in his education. For instance, as an older student in Chenango County, Joseph was certainly not alone. The county was consistently one of the highest in the state for teaching youths both younger and older than the statewide category of students “between the ages of five and fifteen years.” When he attended school, Smith was one of 238 students who fell outside the range of five to fifteen years, which amounted to 23.3 percent of the total 1,023 taught. Assuming half of those students were older than fifteen (state statistics unfortunately group the two age groups together), then roughly 12 percent of the students were older than the five to fifteen category. In other words, when Joseph, age nineteen, started the winter term in Chenango County, roughly 12 percent of his classmates were also older than fifteen.Josiah Stowell, Jr., in fact, who was born April 16, 1809, was himself sixteen years of age when he attended school with Joseph, and would turn seventeen before the end of the school year. Thus, Joseph’s attendance may reflect his desire to participate in the same activities as his peers, as much as a personal desire to improve his education.

Regardless of his reasoning, however, Joseph’s time in school would not have been idle, and his age suggests an important role he may have played in the classroom. Older students were regularly enlisted as teaching assistants when the class was separated into groups, according to skill levels. For several years prior to this time, several New York schools were also experimenting with a new form of pedagogy known as the Lancasterian system.In this model, older students, under direction of the schoolteacher, participated in the teaching process by guiding younger students in their exercises. It is possible that Smith may have been acting as a monitor, though the historical record is unfortunately silent on such details. Yet, such participation well may have influenced Joseph’s desires to teach: he would eventually instruct members of the “school of the prophets” in grammar, as well as teach grammar to his family.In any event, the 1825–1826 winter term was likely the last time Smith attended class in a common school.

Tallying the Time

Throughout this essay, I have revisited several of the claims and historical accounts regarding Joseph’s formal education in an effort to interrogate popular notions regarding his level of literacy. I believe a close examination of the existing evidence confirms that Joseph Sr. and Lucy faced significant challenges in providing a formal education for their children. Frequent relocation, illness, and financial exigencies would have contributed to a string of interruptions, resulting in gaps and intermittent school attendance over the years. At the same time, however, the historical accounts reflect the family’s recognition of the importance of education and a persistent effort to obtain it. And if the available historical references provide relatively accurate representations, then the overall amount of Joseph’s formal education requires significant upward revision.

Because the historical record does not precisely identify each and every term Joseph attended school, a countless number of speculative combinations can be formulated either to expand excessively or minimize unnecessarily the number of his years of formal education. On one hand, we might claim Joseph rarely attended school, regardless of the available evidence. On the other hand, we might claim Joseph attended, in full or in part, every school term that he would have been eligible to attend (excluding, of course, his times of illness and the summer terms when he was likely working), spanning from the 1809–1810 winter term in Royalton, Vermont (the term in which Joseph turned four years of age and became eligible to attend school) to the 1825–1826 term in South Bainbridge, New York (the last known school term Joseph attended, when he turned twenty years of age). In the latter case, the total number of school terms that Joseph was technically eligible to attend during those fifteen years would have included six full winter terms, six full summer terms, and nine partial winter terms—or approximately ten years of school (see Appendix A for a year-by-year breakdown). What Joseph actually experienced in his life, of course, would surely have occurred somewhere in between these two extremes. To that end, this essay will attempt to minimize speculation by outlining a scenario of Joseph’s participation in formal schooling that is grounded in direct and indirect historical references.

Junius Wells provides the first reference to Joseph’s formal education by claiming that Joseph learned his letters from Deacon Jonathan Kinney in Vermont. This requires a minimum of one school term. If we assume he did not begin school until the 1810 summer term (delaying his start until he was four and a half years old), and if we also assume the Smith family moved to West Lebanon in the fall of 1811, then Joseph could have attended school in Royalton for three full terms (summer 1810, winter 1810–1811, summer 1811). Yet, this is the same period when Lucy claimed the Smith children had been deprived of the benefit of an education. Therefore, we will limit the estimate of Joseph’s time to the winter 1810–1811 school term.

Next, assuming Lucy’s dates, the Smith family moved to West Lebanon in the fall or winter of 1811, which would allow Joseph to attend the 1812 school year (winter 1811–1812 and summer 1812). As discussed earlier, Lucy stated in her history that all the Smith children who “were of sufficient age” were sent to a local common school. Joseph, who turned six years of age during the 1811–1812 winter term, would have been included. This brings the total amount of Joseph’s formal education to two winter terms and one summer term, or approximately one and a half school years.

In the 1812 to 1813 winter, Joseph fell ill. Though he likely started the winter term, Joseph would have withdrawn early, as the leg surgery and subsequent convalescence would have prevented him from attending school for the remainder of the term. Joseph most likely missed the following summer 1813 term, as well. One year after the surgery, Lucy stated that everyone in the family returned to health. No longer bedridden, though still lame and using crutches, Joseph would have had the opportunity to return to school and pick up where he left off. Thus, between the first half of the 1812–1813 winter term, combined with the latter half of the 1813–1814 winter term, Joseph would add the equivalent of one more winter term. This raises the estimated amount of formal education to approximately two school years.

Even though Joseph remained on crutches until the family moved to Palmyra, Lucy’s claim that all the children in the family returned to health further suggests that Joseph’s condition allowed him to return to school for the remainder of the Smith family’s time in the Upper Connecticut Valley. Furthermore, Joseph’s continued physical challenges that would have prevented heavy farm labor, would have allowed him to attend school during the summer terms. Nevertheless, for this estimate, I will not include any summer school sessions for this period. Rather, for the sake of argument, this scenario will assume that family exigencies did not permit Joseph to attend during these summers, though he was apparently physically capable to do so. This results in the equivalent of approximately one more year of formal school (winter 1814–1815 and winter 1815–1816). Joseph’s total time in formal school would then be the equivalent of just over three years.

Sometime during the winter of 1816 to 1817, the Lucy and the children spent one month relocating to Palmyra, New York, from Nor wich, Vermont. Once the family arrived, Lucy and Joseph Sr. appear to have enrolled the children in school for the remainder of the winter term (February and March). Between starting the winter term in Norwich, withdrawing to prepare for and complete the move to New York, and then finishing the term in Palmyra, the Smith children may have attended between two to three months for the winter 1816–1817 term. This estimate will limit the school time to the final two months in Palmyra, bringing Joseph’s total school time to approximately three and a half years.

Shortly after their arrival in Palmyra, the Smiths held a family council and determined to pool their efforts in an attempt to get established. Therefore, in this scenario we will assume that Joseph, now eleven years old, began to work the same seasonal schedule as an adult, splitting time between family labors and hiring out to local farms and employers. This also means that from this time forward, Joseph would miss all future summer school sessions. Furthermore, he would start late in every ensuing winter term (thus limiting his time in school to between four and five months per year). We will also assume Joseph worked this same schedule during every subsequent harvest season, both in Palmyra and Manchester. Using the property tax records as a guide, Joseph’s partial attendance during the winters would include four months of each winter term in 1817–1818, 1818–1819, and 1819–1820. This brings to the total time to the equivalent of approximately five years of formal schooling.

Several accounts from former classmates indicate Joseph also attended school in Manchester, which requires a minimum of one partial winter term (winter 1820–1821). During this period, Joseph participated in a juvenile debate club, which reveals his interest in self improvement—an activity that also suggests continued attendance at school. Furthermore, Joseph’s possession of advanced school texts, particularly Murray’s English Reader and Charles Goodrich’s A History of the United States of America, alerts us to his level of achievement within the common school system. Therefore, this estimate will propose that Joseph potentially attended school in Manchester during the 1820–1821, 1821–1822, and 1822–1823 winter terms. This intermittent attendance equates to one school year and approximately four months, raising Joseph’s total estimated time in formal school to six years and approximately four months. Finally, this scenario will assume that Joseph did not attend school, in either the winter or summer terms, during the 1824 or 1825 school years. Thus, the last time Joseph attended a common school would be the 1825–1826 winter term in South Bainbridge, Chenango County. This final term increases the overall estimated time that Joseph spent in formal education to the equivalent of approximately seven full school years—a notable increase to that proposed in previous historical representations, and one that will require the careful evaluation of future historians.

Because of the several gaps in the historical record, this estimate, of course, can either be increased or decreased, according to any given historian’s perceptions and intents. In any case, however, the overall combined effect of historical sources points to a higher amount of Joseph’s formal education than is traditionally acknowledged. My aim, however, is not to assert a specific figure of time; other supportable estimates certainly exist. Rather, I want to highlight the implications that can emerge when traditions and cultural contexts are brought into discussion with a detailed review of historical evidence: such incongruence, even when resistant to definitive measurements and final authoritative claims, opens windows to neglected historical narratives.

Another Facet of Joseph’s Life

Joseph Smith’s dynamic transformation from an uneducated farm boy to an exalted prophet of God remains deeply entangled in cultural traditions, religious identification, and the Mormon cosmology of faith. Yet, an excavation below the often-hagiographical representations reveals a narrative of Smith’s life that is equally compelling for its resonance with the individual struggle for respect and self-determination. Regardless what praise or criticism would be heaped upon his memory, Smith rose to prominence through tenacious determination, persistent hard work, and systematic self-improvement. Moreover, Smith’s formal study would surely have been complemented by informal avenues of education, including instruction at home, reading, attendance at Sunday school, participation in a juvenile debate society, and even his preparations to become a Methodist exhorter.One could argue that Smith, like so many of his ambitious fellow citizens in a striving nation, was above all an autodidact. The story of a young man, struggling against eco nomic disadvantages and intermittent opportunities to attend school, would be inspirational and serve as a prime model for Mormon ethics of industriousness and productivity, were it not overshadowed by the near-exclusive enlistment of Smith’s early life as evidence of divine manifestations beyond his humble and “uneducated” capabilities. Nei ther would Smith be an easy target for critics hoping to portray him as an illiterate farm boy who duped a bunch of so-called gullible, illiterate folk into following him. For below the surface of both idealized and demeaning stories, a persistent pattern of ambitious preparation begins to emerge, revealing the narrative of an individual’s yearning to overcome his seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieve a prominent role in public life and religious leadership. Smith’s story truly exemplifies the ideological aspirations and ambitions of early nineteenth-century Americans, though the narrative of his self-motivated ascendance has receded into the background. It is, however, a story that deserves more nuanced respect, greater attention, and continued research.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue