Articles/Essays – Volume 48, No. 4

Spencer Kimball’s Record Collection

I should keep a journal. If I did I could look up what year this happened. Or exactly why I drove to Ed’s house and knocked on his door. Or what time it was when he phoned me up weeks later to make his offer. But it all happened. I’ve got the proof on my shelves. Well, some of it, anyway.

Ed Kimball lives up in the foothills behind the Provo Temple, a few blocks north of what they call “Indian Hills,” a place with the names of Native American tribes on block after block of street signs. Fitting, I thought as I headed up the shaded gravel driveway of this son of the twelfth president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. If William J. Clinton was our country’s first black president, as we used to say, Spencer W. Kimball was our Church’s first Indian president. An Arizona desert-raised son of a missionary to over twenty nations of Native Americans— “Lamanites,” in Mormon parlance—Kimball focused his vision on these indigenous peoples more than any Mormon apostle before or since. As president of the Church, he’d moved thousands of Native Americans off the reservations for schooling, deepened the bank accounts that funded Lamanite scholarships at BYU, and generally jacked up the top-level rhetoric about white Mormons’ duty to those with browner skin.

Ed, Spencer’s third son, co-wrote with his nephew the whiz bang biography of Spencer that knocked us flat in 1977 for its candid, full-blooded look at a sitting Church president’s life to that point. Is this how biographies would be written in the Church now, we wondered? (The answer was . . . sort of, sometimes, maybe.) When I went to Ed’s house, I asked him questions about his dad and music and specifically if there was anything in Spencer’s diaries about Jay Welch’s firing from the Tabernacle Choir.

He graciously looked up some dates for me. Not much there. When I asked about the couple hundred LPs on the shelf near where we sat, Ed told me that, yes, those were his dad’s. Could I look through them, I asked? Sure, he said. Did he want to sell any of them? No, but if I wanted any of them, I could have them.

Now, I had been collecting records since I was nine. By this point in my life, records seemed to wash up on my shore from the strangest places. But this was the unlikeliest: the record collection of one of my heroes, samples free for the taking. Still, the historian in me—along with a dime’s worth of tact—made me focus on the content of the collection, what it might reveal about its owner, and be sparing about what I grabbed up.

Many of the records were gifts to Spencer. The usual, expected “official” gifts, of course: records by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, the Mormon Youth Symphony and Chorus, M.I.A. conference choirs, Temple pageant casts, and so forth. Most of these LPs were still sealed and had a note on them gifting them to President Kimball. There were also gifts from ad hoc Mormon choirs I’d not heard of: The Mormon Expo Choir, the Detroit Mormon Concert Choir, the Indianapolis 4th Ward Choir, etc.

But many other gift records came from Native American soloists and groups, inscribed by their makers with love and thanks and all else one might expect from citizens of a Mormon nation of tribes that lionized Kimball. These I gingerly started to pull off the shelf to take home, though I had impure motives. I’d sold some limited-pressing Native American records on eBay, including one I saw here in better condition, and thought I might put some (read: all) of these up for auction, too.

I saw a few international records—Mexican mariachi bands, Russian Orthodox church music, Greek dance records, British organ recitals. There was classical, mostly “Best of ”-type collections, 25 Most Beloved Melodies, and the 1941 Music Lovers Chest of Records set. There was even some pop, ranging from Jim Reeves to ELO to Gene Cotton to Simon and Garfunkel to Bob Dylan. In all fairness, Ed assured me, some of these probably got stuck on the shelves by grandchildren.

I asked him about his dad’s listening habits. While working at his desk at home, Ed said, Spencer liked to listen to Hawaiian music. Before becoming president of the Church at the end of 1973, Spencer “went to the symphony with some regularity.” But after he took the Church’s top post, that stopped. Too busy. What was the main thing that governed Spencer’s record-buying habits? “He was thrifty,” Ed said. That was why two-thirds to three-fourths of the records in his collection were gifts.

Besides the Lamanite records, I took one or two others and headed out to the car. I shouted thanks to Ed from my window as I drove away.

I did sell that one record I’d sold before on eBay. Most of the others I crammed into the “LDS” corner of my collection, a fat row of LPs between a three-high-shelf and a two-drawer file cabinet.

A few weeks later the phone rang and it was Ed. “How would you feel about just taking all of Dad’s records?” he asked.

“Hmm.” I said. My heart raced in two directions: I loved the thought of getting this collection, but didn’t love the thought of having it. Because (a) I wasn’t an archive or storage facility, (b) there wasn’t much of musical interest in these discs, and (c) I didn’t know the provenance of some of the more interesting records. My greed and savvy both kicked into gear.

“I’d take them on the condition that you understand most of them will end up at the D.I.,” I said. (“The D.I.” is how Mormons refer to Deseret Industries, the Mormon equivalent of Goodwill or the Salvation Army.) I explained my reasons for wanting to get them but not keep many, how I’d sort them, and such.

“That’s okay,” he said. He could use the room. And they weren’t being used. Like most people, he’d shifted to FM and CDs when he listened to music at all. So these foot-wide black vinyl discs were just trinkets of a life and relationship from which he had much more intimate and more usable trinkets already.

I drove to his house, parked my red ʼ93 Taurus close to the front door, and knocked. He let me in and we started looking for boxes to pack up the records. When we’d filled a few boxes, he said, “There’re more records downstairs.” We walked into his basement and the first thing that caught my eye was the tall bookshelf of binders: all of Spencer Kimball’s looseleaf diaries. I wanted nothing so much as to spend the rest of the day—the rest of the month—leafing through them and taking notes. But I was on a mission. And besides, though you wouldn’t think this of me, I was bashful. “Those are his diaries, huh?” was all I said. “Yes,” he said. And that was that.

He asked me if I wanted an old dictaphone his dad had used, but I didn’t. Too clunky. Then he showed me what turned out to be the treasure. Second-hand treasure, that is. Two boxes filled with 12-inch classical albums—78 rpm albums, that is, sets of several discs each, bound into an actual hinged album to yield, say, a single symphony. “Those were my brother Spencer’s,” Ed said. “But when he moved back east to go to school, they were too heavy and breakable to take with him. So he left them with Dad.”

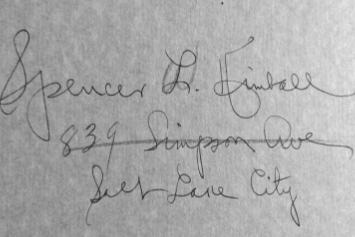

Now I thought I was getting somewhere. They were all classical and fit better with what I thought a prophet should be soaking up. “Did your dad listen to them?” “Some of them. You can tell the ones he liked by looking inside the front cover. This one, for example, was one of his favorites.” He handed me the 1950 five-disc Victor album of Pierre Monteux conducting the San Francisco Symphony in the Franck Symphony in D Minor—one of my favorite pieces when I was in high school. I opened the cover and saw the inscription on the left, written in black ballpoint:

Spencer L. Kimball

839 Simpson Ave.

Salt Lake City

In red pencil someone had crossed out the street address and written a “W” over the “L.” “That’s how Dad showed which ones he was claiming for himself,” Ed said. “He crossed out the address and wrote his middle initial over my brother’s.”

After flipping through all the albums in these boxes, I carried them and the other boxes out to the car, putting half in the trunk and half in the back seat. I thanked him again, then drove home. When I got there, Pam was home and I told her all about what had just happened. Then I started to sort through the records.

Even before I’d picked up the discs at Ed’s, I knew the three categories: records I wanted to keep, ones I wanted to give to the BYU library, and ones I was hauling to the D.I. I worked quickly and within a couple of hours I had the basic sorting done.

There were only a few of this new batch that I wanted to keep: a Mötley Crüe album (obviously a grandkid stray), Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, a few more LDS artists and pageant soundtracks for my Mormon music corner and, no surprise, the Franck. I picked out a batch of records I thought might make a nice mini-archive in BYU Special Collections: unusual records owned by a Church president, which included the other re-initialed albums and a couple of one-off 7-inch field recordings of tribal singing, presumably given to him by a missionary or Lamanite admirer. All the rest: the D.I.

A few days after my donation, I was in the D.I.—I used to go at least once every day back then—and saw that these records had just come out and were in the racks. Two women with British accents were admiring one dark blue box set from the batch, the 1975 BYU centennial 4-disc Sounds of a Century commemorative set of speeches. This set only rarely appeared at the D.I. and I knew from this one’s condition and a couple of distinctive marks that it was indeed the one I’d brought from Kimball’s shelf, the complimentary copy BYU had given him.

I had to say something. “I know this sounds weird and you’ll probably think I’m making this up, but I know for a fact that that copy you’re holding belonged to President Kimball.”

Their eyes widened and before they could say more than “Really?” I told them the whole story and how I knew this was his personal copy. They both said that this was a treasure they would love to take back to England. Cost? One dollar.

“If you want, I can write you a certificate of authenticity and sign it so you have something to back you up.” One of the women found a grocery receipt in her purse and I wrote my ad hoc certificate on the other side of it. They thanked me over and over and I thought maybe I should just stay around for awhile and tell people when they picked up a Kimball record. But the impulse quickly passed and I drove home.

As for the BYU records, I found out later that they didn’t all stay together, as I’d hoped. The titles got processed like any other donation, duplicates probably got sold off or given away, including the initialed 78s. The Lamanite 7-inchers are in Special Collections, but you have to know their names to find them. And, truth be told, who knows if President Kimball listened to them at all, let alone liked them? From some of his sermons, I’m pretty sure he thought Lamanite music was as savage as, well, the Book of Mormon Lamanites.

As for the ones I kept, understand the situation: all of my 7,000+ records stand in eighty-some shelf cubicles, or perch on top of the shelves, or lean against walls, or sit in bins in an oblong room above our garage, a mini-warehouse that also holds stereo components, rock posters, art prints, books on cartooning and Persian rugs, my large Annette Funicello collection, hundreds of rare and bargain basement pop CDs, dozens of horror DVDs, and VHS tapes of B-movies and interviews with poets, cassette mix tapes I made for my wife’s old aerobics class, binders full of movie stills and promo photos and postcards, file drawers stuffed with book contracts and folders of articles I’ll probably never read again, piles of mailing supplies, and, stuck in spaces here and there, autographed pictures of everyone from Joey Bishop to Anna Nicole Smith. Amid all that, the record collection—and my memory—has swallowed up the few Kimball records I stowed there.

There are just two things in plain view in this room that remind me of President Kimball. One is that Franck album, which sits at the front of a thick group of about eighty albums leaning crosswise on another long stretch of about two hundred sitting on top of a pressboard shelf. The cover is one of the real works of art in the room: a flag-draped rifle bayonet in front of a ghoulish hand reaching up from a pool of blood inside a flame tongue rising from a burnt-out cityscape. It’s quite extraordinary: a semi-kitschy outtake from the Nazis’ “Forbidden Art” hall of shame. It reminds me of that mongrel post-war era when both a cheery Apostle Kimball and post-Holocaust dread flourished side by side in this country.

The other, far gentler, mark of his presence is not a record at all. It’s one of the boxes I carried his records home in. Ed and I had scrounged around in the basement till he asked me if this one would be okay: a large, lidded cardboard cube covered with color photographs of sky and clouds. A gift shop oddity from the ’70s, I’d say. A tourist-class disposable prop. It’s breezy and chic. It’s the flip side of the Franck.

I’ve used the box for years to haul toys from floor to floor or to stow books for Mormon research or, now, to hold up my cassette deck because the cord that runs from it to my Denon receiver isn’t long enough for the deck to sit on the floor, where I’d prefer it to be. I’m looking at the box right now, a firm but hollow foundation for an outdated technology I still insist on using. Though partly cloudy, the box shines: beams from wherever it sits. And it has sat in every room in our house over the years since I got it from Ed’s house. Where will it be in a month? I don’t know. And that, I guess, is the continuing revelation of it, this portable, smiling souvenir of a prophet.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue