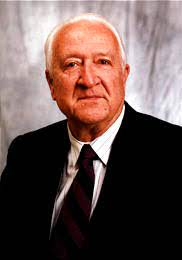

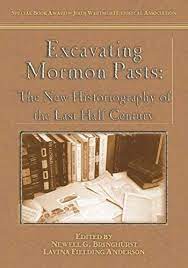

A Scholarly Tribute to Leonard Arrington | Special Collections and Archives, Utah State University Libraries, The Collected Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures

March 22, 2018Contained in this informative volume are ten essays originally delivered as annual lectures from 1995 through 2004 honoring Leonard J. Arrington, renowned scholar of Utah-Mormon history, former LDS Church Historian, and one-time Utah State University…