Articles/Essays – Volume 49, No. 4

Flaming

One day, I woke up blinded by white light stinging my sleeping eyes. A thin, radiant line created by a break in my window blinds had been making a slow sojourn, day by day, across the floor of my room. Through out the year it crept toward me, persistent yet hardly perceptible until one day—this day—it hit me in the face. It was as though the planets and stars had conspired to deliver a celestial wake-up call, inevitable and inexorable. And yet, despite the months I had spent in bed, sleeping my days away in a stunned indifference that made things like class assignments, eating, and showering entirely inconsequential, I hadn’t seen it coming.

Is this how it was for Joseph? Before I could stop myself, I mentally replayed that moment from the First Vision when Joseph raises his arm to shield his eyes from the light, a composite memory crafted from the movies, pictures, and representations of the scene I had seen over my life. I kicked myself: how immured was I to that story that it was the first thing I should think of at the moment a thin slit of light should wake me up? Will I ever stop thinking the Mormon thing first? Will these stories and images fade once I leave BYU?

It was early afternoon. Two adult voices wafted in through the window from the sidewalk in front of my apartment. I’d obtained permission from the university to live there after falsely claiming that my psychiatrist believed my mental health depended on living outside of BYU-approved housing, but the campus worldview still managed to invade my life: my fellow students were cheerily making their way up to campus, brightly discussing their upcoming Book of Mormon exam, their ward activity next week. Their laughter reminded me once again that my months of depression and frustration were all but invisible to my classmates.

I rolled over in my bed, away from the light, and my glance fell onto the space made by my open closet door across the room. Within, a large Rubbermaid container nestled below my hanging dress shirts. The opaque plastic obscured the contents, but I knew exactly what the Rubbermaid contained. I stared.

And what am I going to do with you? The blinding light. The heat. All this anger.

The answer hit me.

I searched my sheets for my phone and rapidly punched out the text message.

“Caitie? Can we go camping?”

I waited, staring at the screen.

“I need to build a fire,” I added.

I waited again.

“Of course!” she replied. “What do you need to burn?”

***

“Craig. Listen to me. I want you to go into the garage, put some tin foil on the ground, and burn these.”

My mom hands me a snack-sized plastic baggie. I blink, confused. Why would she ask her ten-year-old son to start a fire in the garage? Not only is the task odd but she is using the voice. The this is important voice. And not just generally important. Church important. Which means very important. When she speaks of very important Church things, her voice diminuendos to a whisper, higher pitched than normal and wobbling with tempered emotionality. She uses this voice when she talks about receiving answers to her morning prayers or thanks my dad after he blesses her when she is sick. I hear other people use their own version of this voice at church, when they speak of temples and faith, of pioneers and Joseph.

She tugs the Ziploc bag open and pulls out a single small square of white fabric.

“These pieces of fabric come from garments. Do you know what garments are?” she asks.

Like so many raised in Mormon homes, I know what garments are—those white underclothes—while at the same time having no idea what garments are. I’ve seen my mom sort our family’s dirty clothing into mountainous color-coded piles on our laundry room’s cold cement floor. Sitting in a corner unloading hamper after hamper, she tosses each skirt or slip or sock into its appropriate pile across the room, pausing her efficient system only when she arrives at one of the white pieces, her hands running over the fabric, feeling for that silky coolness that immediately indicates “garments.” Instead of flinging them into a pile like the clothes that proceeded them, she gently places each top or bottom in its own basket on the washing machine. Now I tell her I know what garments are, but all I really know is that they’re clothes so sacred she won’t even let them touch the ground.

***

Childhood in Mormonism is an experience in prolonged observation. Before age twelve, there are no real obligations other than to sit in pews, sing songs, and dutifully go to class. And that’s where it ends. Children don’t teach or lead and aren’t called on in the night to put on a white shirt and tie to bless someone. Kids sit outside the temples while every one else goes in. While narratives of joining Mormonism condense the journey of conversion into a single moment of baptism, the reality is that induction into Mormon identity occurs slowly. It begins as emanations from orthodox sources. But it occurs even more potently through anecdotes created by experts fluent in that spirit of Mormonism that resists being distilled into the manuals, like my mother teaching me as she placed a baggie of fabric into my outstretched hand or separated her garments for washing. There are thousands of Mormon myths and mysteries, rules of conduct, and unofficial norms of behavior taught outside Sunday school classrooms. To be told something is sacred is to be given that thing to protect. It’s insider knowledge of the rules that dictate our Mormon world. With each telling, one is brought out of the role of observer and transformed into participant: into being Mormon.

***

“I want to burn everything in the Rubbermaid.”

It took Caitie about three seconds to reply in all caps: “I’M IN!”

I’d explained the Rubbermaid to Caitie, my sympathetic feminist friend, a few months prior when we were discussing the last time either of us had gone to the temple. Our conversations often orbited around Mormonism, spontaneous self-directed therapy sessions that broke out in the sheer joy of being able to talk with another person who understood what it was like to have believed. When we met two years earlier, I was a teacher at the Provo Missionary Training Center who attended the temple three or four times a week with one singular, nagging question: what should this gay part of my soul become? I had always known I was gay but spent most of my time trying to convince myself I was only a little bit gay. Not so gay that I couldn’t get married. Not so gay that I couldn’t be Mormon. I used language like “same-gender attraction” to prevent myself from forming a gay identity. It wasn’t something I was because I always spoke of it as something I struggled with, like some incurable disease.

It wasn’t until after my mission when cultural obligations to seriously date and get married forced me to deal with what I had avoided for years. The last time I attended the temple, I suddenly saw the endowment as a gay person instead of experiencing it through the aspirational eyes of the man I desperately wanted to be. Previously, the temple embodied a well-trod path leading to marriage, fatherhood, a sense of purpose within my community, service, goodness, engagement with the present and with eternity. But on that last day, all that was gone. I didn’t feel attacked or marginalized, cast out or hated. Simply unconsidered. Not included in the narrative being presented. A silent, dull slap from a God who had long since gone quiet. There was no bitterness in the delivery, just recognition from both parties that this is the way it is and that this was not for me.

In the months that followed, I started to feel as though I were living among some other person’s belongings every time I entered my apartment. There was just so much Mormon stuff I had never noticed before. My apartment was littered with institute manuals, seminary manuals, scriptures, gospel commentaries, study guides, artwork, souvenirs from my mission, books, journals, magazines, posters, and pamphlets. I owned a closetful of ties, shoes, dress pants, belts, suit coats—and temple clothing. Including garments.

As my faith and identity oscillated, so did my connection to these objects. They began to feel painfully foreign to me, like relics of some past life I had lived or bitterness-evoking mementos of a horribly failed relationship, their mere presence powerful enough to take me back to the trauma of what I was just coming out of. They highlighted the Mormon backdrop my life had depended on and accentuated my deep sense of lost identity. The objects made me feel like an impostor. It was as though at any moment, some righteous priesthood holder whose room I was surreptitiously occupying would return and cast me out with a disarming smile, arm most likely at the square, muttering “faggot” under his breath as I closed the door behind me.

Unsure of what to do with these remnants of my Mormonism, I began to fill a Rubbermaid container my mom gave me when I moved to Provo for college. Every time I encountered some item that radiated Mormon-ness, I put it in the Rubbermaid in the closet and did my best to forget about it. With time, the Rubbermaid overflowed as the relics of Mormonism were replaced with new and exciting parts of myself: books about the beauty and history of my gay tribe, campy movies, and old Judy Garland albums. It was Caitie who noticed the reversal of metaphor. As my de facto therapist, she wisely pointed out that I had let the gay part of myself out of the closet and forced the Mormon to take the empty spot in the Rubbermaid as if in cruel retribution for all the years I spent hiding out in there. She called it my spiritual spring-cleaning.

“This is going to be a big fire,” she texted me now.

***

The closets we maintain as gay people can be cavernous. Though we blame society for putting us in these dark, lonely caves, it is the closets we create ourselves that are the hardest to leave behind. In our closets, we hide the people we were born to be, the indicators of our difference we don’t want others to perceive. We fill our closets with those questions that scare us, those thoughts that, if acknowledged, might prove too difficult to simply ignore. Mormons do this too, metaphorically “shelving” difficult questions until they’re ready to be dealt with. We hide away lists of queries unanswered by a God whose voice thunders loudly, commandingly, at certain other times. We hide away stories from our history that don’t make sense to us or feel foreign to the church we now find ourselves in. We put away what we cannot know, hoping to receive answers on some distant, nameless day.

But just as questions demand answers, closets eventually require opening.

***

“Garments are sacred.”

I nod. My mom makes direct eye contact with me over the top of her glasses, curlers taming her long, fiery hair as they do for hours before church most Sunday mornings.

“And because they’re sacred, we don’t just throw them away when they get old and worn out. Instead, we cut out these special parts of the garments called ‘marks.’”

She runs her finger along a nearly-imperceptible stitch of white thread in the square she holds in her hand. “Once you cut out these special parts, the garments aren’t garments anymore. They’re just regular pieces of fabric that can be used for whatever you want. But we burn the marks to show God our love and reverence for the garment. This is how he wants it to be done.”

My mind flashes to my Thursday night Boy Scout meetings at the church. Our troop leader owns a flag store and has taught us appropriate flag protocol with military exactness. He’s explained that when an American flag gets old and tattered, it is respectfully burned. Flags don’t touch the ground either, just like garments. What is it about garments and flags that make them so powerful? And why is it special when we burn them?

***

The ritual life of Mormonism pivots around rituals of welcoming, coming into, and joining. Through escalating degrees of covenant-making, we are introduced and bound to the magical core of Mormonism through rituals that provide physical, symbolic actions to accompany our increasing devotion. The blessing of a new child is a ritual of welcoming. The preceding generation circles around the new infant in symbolic acceptance. The congregation watches as though to say, “You are ours and we are yours. This faith is your birthright. You will tell your own version of this story. You will walk your own incarnation of this path. And it will be a Mormon path.”

I felt the welcome of ritual when I was baptized and confirmed, surrounded by a circle of men, sensing my potential to grow to be their equal. I felt the same welcome on the day of my priesthood ordination, when I received my mission call, in that moment I rounded the corner into the temple’s celestial room for the first time, greeted by the warm smiles and hugs of my family. Each step welcomes us to a new degree of observance, an intensified sense of commitment. When performed in the prescribed way and in the appointed time, our rituals of welcoming are real and powerful.

But there are also rituals of leaving, symbolic actions we perform to honor what once was in order to leave behind what has grown old and no longer fits. These are rituals that give us the strength to say goodbye.

***

Caitie and I drove south toward Zion National Park, her recommended campsite. I was fond of the irony. Traveling to Zion? For this?

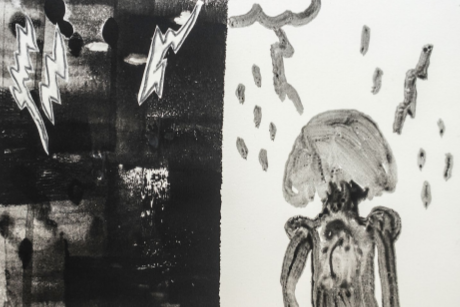

As we drove, I did most of the talking, setting the scene for the evening’s ritual. Like a good friend/therapist, Caitie listened as I told her the history I had learned of BYU’s gay witch hunts, entrapping my newfound ancestors in library bathrooms and scribbling down their license plate numbers outside gay clubs in Salt Lake. I told her I admired those men with faith so strong they did nothing but believe when they were told they could have their beautiful gay souls electrocuted out of them. I told Caitie of the marriages I’d seen broken, of the children left hurt and confused. I told her about the friends I’d taken to the emergency room after their suicide attempts, only to have to show up to class at 8:00 a.m. pretending nothing had happened. I described the feeling of molten anger I carried inside me as I walked the flower bed–lined paths to class. I confessed to the speeches I kept prepared and ready to deliver if I were given a chance to tell everyone, anyone, of the collateral damage BYU was causing. Caitie listened to me explain how I wanted to yell into the face of every student who passed by that his apathy had a name and contributed to the suicide count of my gay brothers and sisters, the ones BYU did nothing to protect or prepare. I tried to articulate that unholy transfiguration that occurs when something you love so deeply becomes something whose presence you cannot stand.

I confessed to Caitie my anger that the gift my Mormon ancestors sacrificed to build was failing so profoundly to live up to its own celestial idealism in regard to its treatment of my LGBT brothers and sisters, my newly-acknowledged family, my tribe. I told her of my pain and guilt, my feeling that I was failing the Mormonism I was born to inherit and practice, as though I were betraying a sacred trust given to me by the universe. I told her how afraid I was because I had lied to my BYU ward bishop to avoid expulsion, to avoid losing my degree, to avoid making those hellish past years worth nothing. I recounted my attempts to numb the pain with anything that would take me away from that place.

Like a wise and true bishop, Caitie listened, allowing me to say what I was not allowed to say to the bishop of my ward. As we drove to Zion, she didn’t try to give me answers, but sat with me and acknowledged my questions.

Eventually we pulled off the highway and made our way to the campsite. It was dark by the time we unloaded the car. I took the wood I had bought at a Smith’s in Provo, along with matches and lighter fluid and, in a moment of rare application of the Boy Scout skills my youth had given me, made a fire. I let it burn until it was large and hot before removing the Rubbermaid from the trunk.

***

The warrior stories of the Book of Mormon never resonated with me. Brothers of Jared and Captains Moroni, Nephis and Almas the Younger were all lost on my budding gay soul. Stories of battles bored me, and the emphasis on doing one’s duty seemed tiresome and juvenile. The complex stories of the women who staccato our Mormon history were the stories that spoke to me. I reveled in the details of the lives of our Elizas and our Emmas when I learned of their unsung spiritual gifts, their singing in tongues and blessing of one another before giving birth—their priestesshood on full display and their community tolerant and grateful for their undeniably divine gifts. I celebrated the faith of these women who gave just as much as the men without being rewarded with power and prestige. Perhaps it was their sheer invisibility that resonated with me—their purer faith that required no recognition?

I thought of how it must have been for them the night before they had to leave Nauvoo. What did they do after they packed their hand carts with their most precious things? Did they clean their houses for future tenants they did not know? My mom would. Did they fold their garments and hide them deep in their wagons? As they walked past the Nauvoo Temple, did they know how they’d miss it? How long did they walk westward before they felt scared? Alone? Confused as to why God would ever make this story theirs?

Tell me they wavered! Please tell me they grew weak and tired as babies cried and winds whipped. Let me take solace in how insurmount able the task they’d been given must have felt to them. What did they have to burn the night before they started their journey? What precious things fueled the fires that gave them the strength to follow their hearts and minds toward their truth, wherever it may lie?

***

As a ten-year-old boy, I take the tin foil into the backyard and fashion a makeshift bowl to gather the ashes. I create a small cone of matches, methodically and reverently, mocking the teepee-style configurations I was required to learn one summer at Scout camp. I light the stack and place a piece of white fabric on top. Each piece burns with a bright burst of light before curling onto itself around the stitched mark and melting away. The burning feels important, holy even. Each piece is used to light the next piece until I have burned my way through the entire bag of scraps. I poke the bubbling spot of melted polyester until I deem it sufficiently destroyed. I crumple up the tin foil and toss it into the trash, returning the emptied plastic bag to my mom to show her the deed is done.

She thanks me.

***

In the campground with Caitie, I opened the Rubbermaid. I assembled the contents on the campsite picnic table. It felt methodical, as though I were cataloguing evidence of a crime. With the items assembled, I began my self-made ritual with no one to instruct me and no elderly volunteer temple worker whispering the steps in my ear. It was instinctual. Unpracticed. It was a ritual born of necessity, not of commandment. I grabbed the pink slip I was given the first time I went to the temple. It had the words “Live Ordinance” written at the top. My mom had told me to hold on to it to be able to remember that day.

I tossed it into the fire.

I took the white temple slippers, coated with soft bumps of rubber for traction on the temple carpets.

I tossed them into the fire.

I grabbed my white tie, the one I wore on my mission during baptisms. I tell Caitie about those people I taught and I wondered how they would look on me in that moment, in front of a fire, burning the reminders of my connection to them. Would they pity me that it had gotten this bad? Would they condemn me? Would they understand? Had any of them loved it enough to be brought to this point?

I tossed the tie, and them, into the fire.

I grabbed the white shirts, the missionary ones with necks worn out from washing them by hand, still stained just slightly red with the dust of Bolivian jungles.

And I tossed them into the fire.

I brushed my hands over the pleats of my white temple robe, the same one my dad had to help me figure out how to put on. I remembered my first time wearing those sacred clothes, how awkward it all felt initially, how familiar it became in the years that followed.

And I tossed it into the fire.

I took the white sash, still rolled up from the last time I used it. I took the white envelope.

And I tossed them into the fire.

I paused at the slick green apron. I told Caitie how I find it comforting that Adam and Eve also had to leave. I thought of the courage of Eve and the wisdom of her disobedience. I thought of my ancestors and how they must have looked in their aprons. I thought of how they would have sewn their aprons themselves, skilled hands getting fussy and particular about the quality of the stitches.

And tossed it into the fire.

I took the letters I’d saved from the woman I’d written on my mission, the letters I thought our someday-children would love to read to know the story of themselves. The letters that began to feel like they were written by some stranger using my name as they toyed with the fantasy of a different, straighter future locked in a relationship whose primary motivation was not love but my own self-loathing, my own desperate need to not be gay.

And threw them into the fire.

I took my missionary tags. I took pamphlets. I took the culmination of a lifetime of Sunday school handouts, of tithing records. I even took a rogue “Personal Management” merit badge book, a stowaway hidden inside my scripture case for a number of years.

And threw them into the fire.

I took Preach My Gospel, in English and Spanish. I took For the Strength of Youth. I took “To Young Men Only.” I took God Loveth His Children. I took “The Family: A Proclamation to the World.” And I tossed them all into the fire.

In the end, all that was left were garments. A small mountain of them. I remembered learning in the temple that God gave the garment to Adam and Eve as a shield and protection to them as they stood on the border of Eden, awaiting their inevitable expulsion. How wise of God to give them some protection in that moment of vulnerability. I paused, sensing my inversion of the symbol. Mormonism was the Eden I was leaving, an ideal world of black and white, devoid of the gay gray I found myself inhabiting. Instead of putting on garments to protect me on my journey, I was taking them off, finally willing to face the world on my own, lone and dreary though it may have felt.

***

In elementary school, I heard a classmate call a character on TV a “flaming faggot.” He hurled his insult at a particularly flamboyant gay man with his wrist cocked limply in front of him, his other hand on his hip, and a voice filled with that melodious singsong quality. Years later, another misinformed friend told me the reason gay people were called “faggots” was because they were burned at the stake during the Inquisition alongside heretics and witches. The “faggots” and the bundles of sticks used to burn and kill them appeared together with such frequency that they became synonyms.

Gay people flame and burn in a way that can’t help but attract the gaze of others, regardless of whether the stares are grounded in envy or disdain. We refuse to fit easily into the categories others depend on to understand the world. Instead, we are drawn to stand on the edges, at the places of transition between male and female, between us and them, between what is acceptable and what is sinful. And there, we flame. We dazzle. We glitter. We congregate around our drag queens covered in their sequins. We flock to our actors, dancers, designers, musicians, poets, writers, and artists listening to the questions we dare to ask.

We also ignite. We burn down the old and the broken in order to make way for the new. Our very existence poses a perpetual challenge to any human’s commitment to “love one another.” Gay people are born into one life that must be shed and have the privilege of coming out into a life of our own creation. In doing this openly and boldly, we invite others to have the courage to do the same.

***

“We don’t waste the garments once we cut out the marks, Craig. We cut up what’s left of the fabric and use it for rags. They make excellent rags for cleaning windows.” My mom is standing at the kitchen counter, her orange-handled fabric shears in hand, cutting strips from a large piece of fabric that has two square holes cut out from the chest.

I think of the rag drawer she keeps in her kitchen, in a smaller Rubbermaid of their own stored below the sink. There are rags made from old T-shirts and bath towels. There are rags that curl at the edges just like this piece of fabric does. “They must be garments,” I think.

“Well, pieces of garments. Decommissioned garments that no longer have their powers because their marks have been removed.” And to think: all this time I had been scrubbing the toilet with my parents’ garments? These clothes, once too sacred to touch the ground, were the same rags we used to clean our dog’s feet when she came inside after it rained?

***

To leave hurts. To ignite, flame, and burn also hurt with their own peculiar twinges of pain. But in order to arrive at something new, we must leave something behind. In order to come into, we must first come out of. How could our tribe, with pioneer prairie dust still fresh on our shoes, ever think otherwise?

“Leave” is a flimsy word. It fails to capture all that’s really going on. To say we are simply “leaving” betrays the soul stretching that has brought us to this point and discounts the wisdom we’ve garnered in the process. Perhaps we prefer to say “leaving” because we are more comfortable focusing on the action itself than really delving into the why. It is as though if we actually spoke about it, we may just discover something ugly about ourselves. We may just be forced to acknowledge our tradition’s own imperfections, our own obvious humanness.

But there can be a dignity in leaving. There can be an art to it and a potential for beauty.

There can be strength and self-respect. It’s simply a language we are yet learning to speak. To leave an Eden, whether by choice or by being cast out, necessitates an endowment of power and protection. To leave can be to arrive at a life that has been growing inside you, albeit silently, preparing to finally, at last, come out.

I have left.

Or have I? It isn’t that easy, is it? As I burned my garments the way my mother taught me, was I honoring or desecrating? Sitting in front of a fire burning the relics of my Mormon life, was I heretic? Or disciple? I do not have the answer. But I know I cannot untie my shoes and walk out of my identity just as I cannot replace the blood that carries this tradition through my veins. I cannot un-serve my mission, no matter how many pairs of pants I burn. No storm can squelch the sunbeam from my soul. It feels futile to try to leave when even leaving is built into our shared Mormon story. Departure and exile are themes we can lay sacred claim to as inheritors of a tradition that had the audacity to walk from New York to Kirtland to Missouri to Nauvoo before departing in order to arrive at yet another promised land.

My Mormonism no longer exists intact. It is not a perfect, pristine garment recently bought and torn from its plastic packaging. I have taken scissors to it, cutting out the portions that itch and chafe. I have cut out baptismal bans and homophobia. I have cut out BYU and the perversion of Mormonism I witnessed harming the many brightly flaming souls who found and find themselves there. I have cut out nervous men who say hurtful things from pulpits who adjust as frequently as their commandments.

And yet, this mangled garment missing its marks that fits only me—that, in spite of myself, I still find myself wrapped in—is not useless. One day I hope to have cut it up and turned it to rags, made it into something useful, something I can clean my house and world with.

***

With tears, I take my garments one by one and toss them into the fire. The fire in front of me billows, melting away the once-sacred remnants of my Mormonism until all that is left is a small smoldering pile of bubbly blackness. I look up at the flaming stars dancing in the sky above Zion. A chilly wind blows through our campsite. I shudder, but smile as I feel the cool air whip up my back, a familiar but new sensation made possible only with garmentless skin.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue