Articles/Essays – Volume 49, No. 4

Ecology of Absence

For starters, the desert is not empty. Things grow in ways you could not dream up. In the Arizona desert, where I was dropped off as a pain-in-the ass teen, there are ocotillo and prickly pear and yucca and all manner of cactus; creosote bushes and mesquite trees with long, knuckly beans; scads of devil’s claw; crucifixion thorns and resurrection plants.

The desert is not unbroken expanse. In the desert there are more things vertical than flat: red canyon walls, mesas and buttes, hoodoos and cairns and geo-acrobatic arches. Not least, the trees. Black walnut, velvet ash and ironwood, oak, alder, Mexican elder, jade-skinned palo verde smooth as scars, and crusty alligator juniper. Why am I surprised? In the heart of nowhere there is always the faint pulse of a seed.

***

Wilderness therapy was a happy accident of Stone Age technology. Effective treatment, a side effect. The intent had been to teach college students primitive survival skills, not life skills, but the fact was young adults were coming home from the middle of nowhere more alive than they’d ever been. The survivalists and their desert experiment couldn’t stay off the map forever. Already a host of psychologists and sociologists had picked up on their little prehistoric operation. Everything must evolve, the survivalists knew. And so it was that the ANASAZI Foundation, the first wilderness therapy program, organically, collaboratively, came to be. Precarious kids, following guides through the Arizona wilderness, would bushwhack their way forward, all the while cutting new synaptic pathways. They called it ANASAZI after the “Ancient Ones,” so named by the Navajo who once inhabited the land on which the teenaged ones tread. Others would come to call it “Treehab.”

***

It was 1962. A group of thirty Brigham Young University students, as part of an academic experiment, were dropped off in the Utah desert with a can of peaches each. They would trek across the blister-red terrain to a pick-up van waiting on the other side, one month away. They would have one guide: a young professor, rangy, enthusiastic, and helpless without his black-framed bottle-glasses. His short hair was crisply parted on one side, but he wore his leather fringe rugged. Larry Olson’s obsession with Native American cultures had lured him into great wastelands as a young boy living in Idaho. He minutely emulated their tools and skills. He became a sophisticate at primitivity. The University had him bring it to the classroom. On meeting him for the first time before the trek, one student recalls thinking, “This skinny white man is gonna get us killed.”

The student was Ezekiel Sanchez, a first-generation college kid of migrant workers, and recently expelled from the University. Indeed, all the students were ex-students. Kicked-out for chronic failing. Only those with nothing left to lose would agree to be guinea pigs without even the shelter of a lab. The deal: the students would be readmitted to BYU if they spent their summer participating in Larry Olson’s rawbrained Stone Age scheme. Ezekiel, back home in Texas hammering once again at the railroad, was fasting when he got the letter of odd invitation. Without the heart to break it to his parents that he would not be returning to school in the fall, Ezekiel had decided to go without food or water until he got a miracle. And so it was. Probation in the wilderness struck him as manna from heaven. He set out for Nowhere, Utah.

Things went south fast in the desert. One guide, and too many lost kids. Olson feared he’d made a fatal mistake. People were starved, injured, sick, falling behind and straying sideways. But then there was Ezekiel. He knew things. Olson had watched him hang back from the group and quietly gather from the land what he needed. Ezekiel’s family had long survived like this. One night, sleepless with anxiety, Olson crawled over to him in the dark. “I need your help,” he said, “or we’re not going to make it.” Ezekiel said he would think about it.

The next day Ezekiel stepped into being a guide, and a month later, the group arrived at their destination. All of the students of the experiment would go on to successfully graduate from the University. Except for one. Ezekiel dropped out of BYU—to accept a position on its faculty. Together he and Larry Olson pioneered a wilderness program and philosophy—the groundwork of what would become a lifelong partnership.

As it became clear that wilderness sojourns were doing something good to people’s brains, Olson and Ezekiel found themselves in a forest of eager experts. Experts from psychology, sociology, psychiatry, juvenile justice, family counseling, education, and a slew of other professions—all wanting to analyze and give suggestions on how to enhance the “primitive experience.” Through trial and error the survivalists sifted through the mass of ideas and methods. They began to find that the more structured or “contrived” experiences often weakened the impact for participants. It seemed that the more hands-off they were about the hands-on wilderness experience, the more positive the results. “Ultimately, when we founded ANASAZI Foundation,” Olson and Ezekiel explained in 1990, “we opted in favor of the original, down-to-earth walking daily—in and with the simple realities of nature.” In the Navajo tradition, life is called a “walking.” ANASAZI named its approach The Making of a Walking.

***

Desert reminds me of a pubescent body. The puckering place where spare warps to bounty: beauty of earthly awkwardness. Angular, flat planes abruptly interrupted by hard outcrops, jutting ribs of rock and sudden softnesses, lonely globules and lanky pinnacles, every inch sloping, carving, filling, outing, all casting oddish shadows. And then there are the sudden shocks of shrubs. Tufts of trees and scratchy patches. You investigate at twilight. How do all these weird growths fit together? What does this place want to be?

***

When I hike into Girls Band I see the matted beehive of auburn hair. It has risen like nut-gnarled bread since I last saw Rebecca two weeks ago. As I get closer I see twigs sticking out.

When she sees who her TrailWalker is she yells, jumps up to hug me, we nearly topple. She shows me her bug bites and brightly tells me a squirrel stole the billionth comb we’ve given her.

You would think she and I were pals by this welcome. I’m always amazed and amused by how even a short time shifts things radically around out here. Not half a moon ago this girl was threatening to kill me with a ridiculously small rock. I met Rebecca when I was called in as emergency support when she dropped her pack and booked it for a dirt road. I wish she had booked it. She mostly trudged in five minute intervals and we sat exposed under the July sun, midday, in the dust. Because Rebecca did not have her pack, I did not have mine, as Trail Walkers are not to have more than the YoungWalkers. This meant I was out my long-sleeve shirt and white scarf, making my face and arms a flesh pile for the bugs to swarm. The gnats caught in the zipper of my eyelashes and tickled up my nostrils and in my ears. When I cracked open an eye to look at the New Jersey girl stubbornly slumped on the dirt next to me, I was appalled to see the bugs had no taste for her. She could sit there all day, and she did.

I know the other two girls as well, Jen and Marian. They are older in years and ANASAZI time than Rebecca. This will be their fourth week— three more to go, if the plan doesn’t change. The plan often changes. These girls only just met Rebecca, who has been a bit too hostile to join the group till now. Of course this is not the explanation we give the girls. We simply say that Rebecca has been on a “walkabout.” ANASAZI uses a “romantic language,” as Ezekiel calls it. He and his wife, who grew up on the Navajo reservation nearby, have crafted a vocabulary in which imagination beats out negative jargon. Rebecca is not a serious case of oppositional defiant disorder; she’s just having her own Walking.

Jen and Marian talk to me excitedly about all the things we have to do this week, like the freaky moon dance we made up, and sewing sexy moccasins.

“And we’re beating the boys to Final D,” Jen crows.

I don’t tell them that we won’t. We definitely won’t. Rebecca’s dreadlocked beehive will be a magic hat of tricks for us this week. I have no idea what will come out of it, but it will likely bite.

***

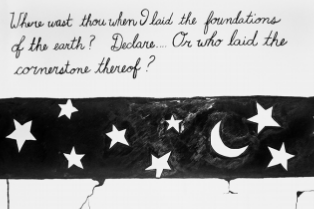

At first blush, the desert appears to be monotone variations on a theme: lack. I don’t know that John Cage spent any time in Arizona, but when he took his seat at the piano before an expectant audience, and played— nothing—this was a movement in desert major. The man sat limpid for a small eternity. The audience got restless, whispery, self-conscious, then noisy. Here is where the key shifted in their brains, and they heard themselves: the audience’s response was the score. The desert is not lack, it is response to lack. It is you hearing yourself.

Desert and speaking are inextricable in Ancient Hebrew, that wilderness tongue, where they share the same root. You can hear the echoes: midbar/medebar. They tell of some innate relationship between the barren, empty, silent, and speaking, language, creativity. Nothing so wants to be filled as silence. The quiet of the desert, going way back, is the beginning of speaking and listening.

People go to the wilderness to hear something. Many people say they do. They call it their inner voice, or their god, or the wind, or the void. ANASAZI calls it the One Who Stands Within.

***

Lack itself signals consciousness. How can something be absent apart from our expectations? Absence is a presence of mind. Henri Bergson said that there are no negatives in nature. A negative description is positively our invention. And so it is that loss and absence, inseparable from our awareness, keep us coming to our senses. They activate us. A person recognizes what is lost and sets out to recover it.

Wilderness makes you all kinds of conscious. Everywhere you look is a lack caught in the headlight of your memories: tap water and ice cubes and shampoo and mom’s chili chicken casserole and a car and roads to drive it on with no aim but to roll down the windows and turn up the music—oh man—music. The kids sit around the fire and incant lists like magic spells. Napping with your cat; green grapes; down comforters; your sister’s laugh when she’s hyper; your Dad making pot roast on Sunday afternoon. More than a torturous mantra, it’s a fine tuning of awareness. Brooding is one thing, dwelling another. The desert mind dwells between two worlds, perceiving “the nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

Lack is generative. When the musician doesn’t play, the audience crescendos.

***

Blandness is a positive quality, Chinese aesthetics would have it. The bland is a full achievement: not the lack of flavor, but the possibility of all flavors. In the colorless, toneless, soundless, inhere all colors, tones, sounds. It’s that temporary moment of loaded indeterminacy: life that has not yet been sacrificed on the altar of particularity: compost of correspondences breaking down to continuities.

The bland longing is not for what has been, but for what has not come into being. The opposite of nostalgia, the bland longs to lose what is particular. It is in the green as it is in the decayed; never in the golden. The bud, and not the flower, is the point.

Blandness. The dull is your oyster knife.

***

Our first day hiking we come upon campers. We’re lucky that this happens rarely—people aren’t exactly flocking to the hellfired wilderness for a weekend getaway. When a tent does crop up, TrailWalkers go into hyper-alert mode. With Rebecca in this group, me and James, my partner TrailWalker, go into heart attack mode. Reflexively we jump to put our bodies between the barbecuers and the girls. In case a YoungWalker makes to hitch a ride with a passing camper or cowboy, we wear a badge on a string around our dirty necks to certify that we are not, in fact, homeless bums who kidnap children.

Rebecca starts hollering and clapping commands—sweetly. Thank goodness—it’s the dog she wants. The mutt wags its tail and starts towards us. I don’t think the campers, veiled as they are by palatial bug nets, have seen us. The dog hesitates. All the girls are slapping their thighs now, cooing and kissing. Come on good boy, almost there . . .

He sniffs the air around us and stops dead in his tracks. You can hear the snort of displeasure as he turns from us and heads back to camp. “Man, even the dogs think we stink,” Marian says.

The desert is a vast defamiliarizer: grass, trees, water, plastics, colors, cars, dogs, and most radically, people, shed their invisible everyday skins, pop like hallucinations. When the backdrop is emptiness, every appearance is a burning bush. I remember that as a YoungWalker, a month deep into the solitude of the desert, bumping into a group of campers fairly blew my mind. You are people! Like I am a person! And we see each other! For the first time in my life I felt what might be called kinship. I loved the strangers, because they were humans. I couldn’t fathom that not long before I had walked through whole crowds of people—real life people!—without so much as looking at them. Didn’t I know what they were? People are too incredibly improbable to overlook. Too impossibly incredible.

The fact of us all being here: way, way too out of this world to not laugh out loud.

***

No place knows more about water than the desert. Its every line and contour, plant and animal, has been sculpted by water, its absence as much as its presence. Lack is its own intimate ecosystem.

I think of desert as the gourmet of water. A glutton will eat without pausing to taste. A gourmet, however, savors not only the meal but the world organized around it—the smells and sounds and placings and pairings, the spaces, lingerings and aftermaths. The desert is a lean muscle toned to taste. A hard tongue that sucks itself dry, plumbing subtleties of wet.

When water itself doesn’t do all the talking, you can catch revealing details about it. There are telling trees in the Arizona desert. A cluster of sycamore is a signal of water, present, or soon to return. Cottonwoods are another inside source. They crowd in rings. Once among them, look around. If there’s a breeze, I would look up, too: a skyfull of silver leaves a’shimmering and shaking. That rustling sound, a susurrus in full sway, is blood buzzing between the temples, or a conch shell cupped over every pore where every pore is an ear. Trees are vascular graffiti saying Water was here.

***

Lack knows more about desire than pleasure physically can. Where pleasure silences desire, lack interrogates it. Pleasure, like all good stories, has a clear beginning and end. Desire is not a good story. It is a dialogue which undermines itself indefinitely. Desire, like the desert, is a skilled curator of lack. It exploits empty space; it is permutational in the extreme. Desire, as long as it lives, evolves. And it can live long, on nothing. In the wilderness desire lives like a Methuselah. Like a Moses, who saw but did not enter the promised land. Desire shows us bittersweet things.

The kids who come to the desert know many things about pleasure but next to nothing about desire. I am one of them, which keeps me coming back to the desert. I want to be a student of desire. I want lack. But not as an end in itself. As a student also of pleasure, I am interested in the way hunger flavors my fill. How contrast cooks with what it has and doesn’t have—to make something fresh.

My greatest desire is to not be used to anything. Here is where lack and desire kiss.

Several TrailWalkers adapt ANASAZI as a physical lifestyle to follow on and off the Trail. While I admire this, it is not my way. There is no pleasure in the world like a gruesome grease binge after a week of barely salted lentils. Even as I appreciate stepping off the tracks of high-speed wish fulfillment, I’m already looking forward to hopping back on. With one subtlety: I know I’d be fine if someday I came home to nothing instead of something.

Larry Olson wrote a classic field book, Outdoor Survival Skills, that we pack around with us on the Trail. I remember reading the prologue as a 15-year-old and coming up short at one of the traits of a “survivor”: a life centered away from comfort and ease. In terms of survival, Olson said, comfort only gets in the way. This odd idea gripped me. What would happen if comfort was no longer a factor in my decisions? What would I do, where would I go? I realized the answer would be: anything and anywhere. If I weren’t afraid of discomfort, what would I fear? I couldn’t think of one thing. I knew I had in my hands powerful medicine.

***

The desert was the death and rebirth of Mormons. Starting in the east, they made their winding way to the uninhabited wilderness of the west. The tales of persecution, trial and tribulation are religiously recounted, and commemorated every year by Mormons on Pioneer Day. The parades and lawn barbecues, fireworks and pool parties don’t do the desert justice. Now in Salt Lake City you can hardly see the desert for the trees. But when the Mormons first rolled up with their dingy wooden carts and undiminished vision of Zion, all the eye could see was a salty blank wasteland.

Who can say what the heart saw? Who knows but the godforsaken has got some fearsome godly glow. As the story’s told, the prophet Brigham Young, shortly after the Saints’ exile from Illinois, was shown in vision a place where the Latter-day Saints would settle and “make the desert blossom like a rose.” Months later when Young was confronted with Utah’s vast emptiness, he could already point to the exact spot where the Temple would go. Zion was a precognition and an ever after re-cognition, because Zion is nowhere to be seen. And so it came to pass that the rundown prophet leading the half-dead group could look out over the middle of nowhere and pronounce it, legendarily, “The right place.”

“His plainspoken direction,” says Our Heritage, “helped the Saints imagine the possibilities of their new home.” Imagination is a tragic optimist. And desert, the topography of tragic optimism. And the God of Abraham, inextricable from both, wrote the tragic optimist’s field guide: “Wilderness and the dry land shall be glad, the desert shall rejoice and blossom; like the crocus it shall blossom abundantly.” How well this god knows us. Man can’t resist irrigating absence.

***

Aiding prophetic fulfillment are the plants themselves, who miraculously outlast the desert’s scarce supplies. Dormancy is a gift of the spirit. Oh to unmanifest, to lie low in possibilities. Euxerophytes, they’re called. True dry plants. In the desert these plants can live true to death for years, decades. Plants in spirit. Just add water, the body will rise.

***

Water is a purely acquired taste. You might say: the acquiring is the taste. There is a story told of a sage who set out to taste the water of all the different springs of the world. He was curious to know the best flavor of all waters. He gave first place to the river of Zhongling, which he found bland at first, but judged gradually to be the best flavor in the world, with which no food can compare. Water is the flavor of sagehood. To taste the richness of the bland is less a matter of receiving a flavor than infusing one: “The sage flavors the flavorless.”

Poor, tired sage traveling the world to compare the forgettable. He must have been very thirsty, with fat fingers and a reeling head, by the time he got to the river of Zhongling and acquired a taste. The flavor of water does not exist independent of insight into its worth.

***

Your ankle’s swollen? You see black spots? You have stomach cramps and a leg rash and, sure enough, you’ve cut the tip of your finger off. Whatever your ailment, the prescription is the same: Drink More Water. Funny, infuriating, and bogusly accurate, Drink More Water is good medicine on ego as well as body. There’s nothing that tests a prideful leper like being told to wash in the river.

ANASAZI’s go-to nurse—a stunning octogenarian who still kills it in high-heels and turquoise jewelry—never stops telling us: Dehydration is the root of all ills. This seems fair, especially from a great-grandmother who can hike to her patients. Dehydration is not unique to the desert. The majority of us are chronically dehydrated, we just don’t know it. It’s too easy to drown out our thirst with superficial fixes that run on medicated empty. The desert doesn’t drain us so much as bring our dry spots to the surface. The sun will have you feel it. But more than we’re getting hammered, we’re hungover. The past catches up with you out here.

***

The first time I met Jen I jumped back a little. She is a beautiful girl. But when we met her eyes were so swollen that they deformed the bridge of her nose, her whole face pocked with black scabs and green ooze. Gnat bites. In the desert, you strain at a gnat or swell up to a camel. They are brutal. We had all been hit hard—summer brought a freak swarm—but none like Jen. Her arms were more scab than skin.

This is not a 16-year old cheerleader’s vision of summer. But Jen is a blend of sweet and tough that makes her persevere politely. She carries her load, she keeps a controlled smile. She doesn’t complain.

But now, in front of me, Jen stops hiking. The group halts and turns to her. Jen is scratching her arms off. Now she is crying. Now sobbing, holding her face. She is moaning, shaking. Saying over and over, I can’t do this anymore. Home, I want home.

Everyone knows how she feels, and no one knows what to do. We softly say anything. Our words sound painfully off key. We lower them to a mumble, all but lip-synch, then fall silent. We stand dumbly around Jen as she cries.

Here is one of the hardest parts of the job for me: seeing my agonized younger self, and being powerless to make her believe in me. She will hike through this and past the worst of adolescence. But in this moment, it is the end of the world for Jen. And I can’t be her savior.

The best anyone can do is drink more water.

I take off my bandana and empty my canteen onto it. I lift one of Jen’s arms and begin rubbing it down with the cool water. Jen sniffles and lifts her other arm like a sleepy child who wants to be undressed for bed. I bathe it down to the wrist, and at the back of her neck, and behind her ears. I don’t talk; water is smoother than I am.

James asks Jen if she wants to hike with the bandana. She slowly nods yes. We re-wet it, drape it around her neck. As we set off down the dry creek bed, a ground swell of feeling rocks me. Wonder at water’s power to underwhelm.

***

Whatever is not fully externalized, worries you into worrying it. You rub, pick, dig, turn, the indefinite possibilities deepening in your mind. In this way, absence leaves something leftover. Something hidden within for later development. Absence does not leave us.

Chinese aesthetics expresses this quality as a “lingering.” Whether it’s a tune, a poem, a landscape—holding back initiates overflow.

***

You would think parched land would fling open its doors at the slightest knock of rain. But just the opposite is true. To begin with, most of the desert surface is exposed rock—not particularly absorbent. What surface soil there is expands when wet, essentially sealing off lower layers from needed moisture. The water that does manage to percolate has another problem to deal with: extremely dry soil is difficult to wet. So what’s a good rain to do? Much of the water moves across the surface and headlong down slopes. It collects in arroyos. In times of heavy rain, this runoff can create a flood rushing through the arroyo. Rivers! now-you-see-em, now-you-don’t. We call these flash floods, and we take them very seriously when hiking in the summer. What sounds like a climatic magic trick is actually the number one cause of weather-related death. A torrent of water carrying debris and trees and boulders, rushing at you top-speed on your moments-before dry trail, could saw you in half and end the show there.

The desert can move as fast as it can slow, as wet as it can dry. Not a few groups have lost all their gear to a flash flood. And some of us have had to cling to rocks or branches. But no one has ever gone the way of the flood. In its thirty-some years, there has never been a death at ANASAZI. Ezekiel, when he first arrived to the desert in the creation stages, got to his knees and blessed the land for the people who would walk on it. The walking and kneeling has yet to cease.

The desert landscape is protean to the extreme. Dryness creates run-off, and run-off a flood of possibilities. With the kaleidoscopic flux of surfaces, desert plants and animals evolutionarily shift in turn. All that lack makes for dynamic overflow.

How then is desert life sustained? Internal logic. While the soil of the desert may look pale and dead, the rocks and sand are actually nursing life. Desert pavement—the desert’s top layer of close-fitting stones, like Inca craftsmanship—protects the underlying soil from wind erosion. Protection also exists between sand grains, where there is a live lacework of cyanobacteria. These photosynthetic bacteria interlace fingers to hold soil particles in place. The desert is a survivor. But it digs in its heels below the surface.

***

Rebecca is not going to hike today. She informs us of this after the group spends five hours packing up, downing lentils, killing our fire, no-tracing our camp, planning our route, and, at last, setting off down the ravine. We exhale all that stale air. The mood lightens. How fresh it feels to be moving, to create a however small breeze between us. Fifteen minutes in, Rebecca throws her pack and plops down.

“Whatcha doin’?” James goes for casual.

“This is stupid. I’m not hiking.”

“Well, what do you want to do?”

“Stay here.”

James carefully explains that here we have no water, and no flat ground to make camp.

Rebecca also explains herself clearly: “So.”

Marian kicks a rock and Jen tears up. This is the second day Rebecca has refused to hike. They turn to look at me, pitiful. As if I could regulate. But part of ANASAZI’s empowerment is equal helplessness. In the desert you can’t demand. Only appeal.

An hour later, Rebecca relents enough to backtrack the handful of turf to our starting point. The site is along the dry creek and the dry creek is at the base of a shale and cactus mountain. The girls don’t know yet that we are going to go up then down this mountain, and then another one. James and I don’t know yet how this will happen. When we take out the maps again, look over what’s ahead, we laugh and wipe our foreheads. From here the mountain is an inside joke of indeterminate punch line.

The girls aren’t amused. “Ok, who wants to make the fire we put out?”

***

According to the aesthetic of blandness, what a flavor, tone, or landscape lacks in body, it gains in spiritual presence. The art of the bland is less interested in sating the palate than in leading a person to gain a feeling for the Way. Music is divided into two camps: “One that dazzles the senses and one that awakens consciousness.” This is the age-old tension. François Jullien, in his book In Praise of Blandness, points out that whereas Chinese culture has the myth of silent music, we in the West have the Sirens. Our yearning is for overwhelmed bodily organs.

The desert is not a Siren. It does not dazzle or seduce or bathe itself perennially. The desert is a low, primal growl you discover to be your own stomach. You come to know your hunger; you learn to feed yourself. Indulgence is nowhere in ear shot.

In the desert, you observe, sounds are chewed with the mouth closed.

***

Blandness is the bread and butter of Mormons. I did not say “tea and jam” because Mormons do not drink tea. “Strong drinks,” such as alcohol and coffee, are prohibited. Our church services, like our beverage selection, are prescriptively bland. We don’t have paid ministry, so the Church is run by lay members, untrained in the ways of charismatic preaching. Our sermons, which we do not call sermons but “talks,” are to be plain and straightforward. We sing a little, rock some organ. Instruments with a “prominent or less worshipful sound,” like percussion or brass or an acoustic guitar (for heaven’s sake!), are, according to the Church Handbook, inappropriate. Our church buildings are unadorned. You will not find a cross or altar anywhere. Men have cropped hair and hairless faces; women wear capped-sleeves and below-kneecap skirts. These church meetings are three hours long, for toddlers and teenagers alike. Here is where our Olympic training in understimulation begins. The air is rarefied, the clock is inching up the mount. Our butt muscles ache.

We do not pepper our speech with strong language. We do not have sex—or anything like unto it—before marriage. Our Temples seem secretive, and are indeed exclusive, but serve most often as a very clean space for an afternoon nap. We’re given to shapeless white robes. Our tastes are textureless. Utah has an official State Dessert, and it is Jell-O.

Worship and entertainment have different goals. It would seem Mormon living is boring by design. For it is by boredom that we divine the Holy Spirit, who was not, after all, in the wind, or an earthquake, or a fire, but a still, small voice.

***

Ezekiel and his wife, Pauline, are Native American, and Mormon. There is nothing exotic about this. Mormons and Indians go way back. Mormonism is often called the American religion, and this is true in more than one sense. The Church was not merely founded in America, but its foundation, The Book of Mormon, proclaims to be a record of ancient Americans: their origin, civilization, laws, prophets, progress, downfall and destruction. According to The Book of Mormon, Native Americans are literal descendants of Abraham. This imbued Mormons with a singular view of Indians in the early 19th-century: they were neither the noble savages of literature nor the sub-human brutes of frontier lore. They were technically God’s chosen people. In the 1830s, as the U.S. government passed the Indian Removal Act to push eastern tribes to the western territories, Joseph Smith was proclaiming this land the Native American’s God-given birthright.

Joseph Smith wasted no time in meeting with Native Chiefs and telling them so. This did not sit well with the settlers battling Indians for land. It wasn’t long before the Mormons, pushed out by the same mobs and Congress, followed their tribal brethren to the empty promises of the uninhabited west. From the beginning, Smith saw the establishing of Zion in the wilderness as inseparable from gathering the “lost tribe” of American Indians.

The Book of Mormon is a strange love letter to America’s native. It pleads, it reveals, it evades, it threatens and despairs and dares to hope. It makes impossible promises. The title page of the Book states that it is “written to the Lamanites, who are a remnant of the House of Israel.” The Lamanites were the sometimes righteous, mostly iniquitous people from whom Mormons believe Native Americans, particularly the Navajo, are descended. Some Church leaders have used the terms “Lamanite” and “Navajo” interchangeably, which would kind of be like calling an African a Caininite. In recent years, the Church has advocated for using the quaintly more PC term “children of Lehi” in place of Lamanite. To be a child of Lehi in the Church has special status. Once, touring the roof of the Church Conference Center in Salt Lake City, Ezekiel Sanchez’s face popped out at me from sculpted bronze.

***

Though Mormons have spread out over the world, native interest has never let up. BYU offers programs to learn Navajo as a second language. Selections of the Book of Mormon have been translated into Navajo, and, as early as the 1980s, audio translations of talks by Church leaders have been available. In Snowflake Arizona—a Mormon colony co-founded by my ancestor William Flake, and the dot on the map that makes me related to half the Mormons in Arizona—the Mormon Temple offers its holy services in Navajo. Over 50% of Navajo County, Arizona, is Mormon.

The relationship is not always brotherly. Sharing land, even if it is a wilderness, always breeds complications. To this the good book testifies: tribes split a house as they share it. Across Utah and Arizona, Nevada and Idaho, Mormons and Native Americans overcome and overstep boundaries. One southeastern Utah county, uncomfortably encompassing a rundown Navajo reservation and wealthy Mormon community, has been caught in a storm of lawsuits around racism and inequity. The Navajo and Mormons say they pray for each other, in their peyote ceremonies and sacrament meetings, respectively.

Just north of our ANASAZI stomping ground is the small town, and largest community of the Navajo Nation, Tuba City. The name honors Tuuvi, a Hopi chief who converted to Mormonism in 1870. He invited the Mormons to come settle nearby, and the Navajo and Paiute Indians followed to be near the town’s natural springs.

The Navajo used a different name for Tuba City, Tó Naneesdizí. Tangled waters. Of course. The place where crosscurrents knot together.

***

“In order for a character to be centered and harmonious,” wrote Liu Shao in his treatise on personal aptitudes, “it must be plain, bland, and flavorless. This type of character is thus able to coordinate the five aptitudes and adapt smoothly to all situations.” Only the watery can move with the changing contours of a situation. Ideals become insipid: not goal-driven, but goal-diffused. This bland character, rather than push a

situation in a given direction, exploits it by catching its groove.

At the heart of versatility is a great pumping flatness.

***

It’s unnerving to be so far off our hiking goals. This is a relatively easy week, if you’re going by the maps, but we’re going by humans. Humans have outrageous ridges. When a thing is very steep, it no longer appears on the map as concentric wiggles; it conflates into a single line. It can’t be read. Vertical reality is impossible to map out. You just have to set out.

Human relationships are very vertical climbs. Thick lines where anything can await you.

“Powwow time,” says James. His tense face makes it clear. He and I go off a bit from the girls, still in our sights, but not in our face, and we’re already breathing easier. TrailWalkers must “powwow” daily to counsel about the Band and go over topographical maps, which the kids cannot see. This is the official powwow. But behind the map curtain, is the wowpow. Expletive venting. Which only wants to laugh. Adolescents in the desert say and do the darndest things. If James and I didn’t take time to endear ourselves to chaos, chaos would kick our heads in.

James tells me how Rebecca was bragging to the other girls that she knows all about plants because she eats at Subway like every day.

We break down into giggles.

“Hey what are you guys doing over there?” The kids get jealous.

“Checking maps,” James and I yell back in unison.

“How far are we?” they whine.

“Closer than we’ve ever been.”

Powwows are essential in remembering that we’re not actually concerned about failing to make it to our Final Destination. What is Final D, really? Yes, we need to get there so the kids can get food, letters, see their counselors, and most importantly, so James and I can get out of here. But if we didn’t get there—what? Somehow everyone makes it home, eventually. Final D is just a key for chaos to play in. A point on the map, but never the point.

ANASAZI considers itself a microcosm of the “wilderness of life.” The experience, singular as it feels, is densely fractal. The idea is that the trajectory of one’s Walking in the desert mirrors the course of one’s life. A movement towards reconciliation, home, and a happiness expansive enough to contain unhappiness. As rooted in the physical as life at ANASAZI is, every action has an almost knee-jerk abstraction. Hiking, making fires, learning plants, building shelters, rationing food, finding water, following tracks, burying poo – these resonate at a near allegorical frequency. Experiences bounce between the inescapably physical and the playfully detached. Goals are real, but not. The stakes are high, but blink, and they’re low. Nowhere do I get more caught up in the realness of the moment, or swept away to a more remote distance. I am stressed out and tuned out, totally invested and ultimately indifferent. I am sharply bland.

My parents tell me that they could, in a matter of seconds, make me do or not do anything as a child by beginning to Count To Ten. I never tested them past Seven, and they never had to come up with the meaning of Ten. I think of each day at ANASAZI as a parent counting to Ten. It’s useful to act like there’s a Ten, and freeing to know there’s not. Oh, the genius and grace of arbitrary urgency.

Outside the desert it is far harder to hear the bluff in life’s numbers.

***

ANASAZI has tried to distance itself as much as possible from popular boot camp philosophy. People are often perplexed that I can do this job without being a trained counselor. I’m even less equipped than that— anything I did know of psychology, ANASAZI’s training disabused me of. Its push is away from theory, models, and fixed techniques. The aim is simply to maintain an ancient primitive lifestyle. There are certified therapists who trek out to the desert once a week to meet with the kids, and they are emphatically not called therapists, which word Ezekiel likes to break down as the-rapist. They are called Shadows, which they essentially are, as they follow the experience of the kids and parents far more than they lead it. Nature is given space to do its thing.

The criteria to work at ANASAZI is almost entirely devoid of credentials. It’s a character contract: TrialWalkers during their employment cannot drink alcohol, smoke tobacco, or, awkwardly enough, have sexual relations. We are closer to monks than shrinks. Apart from a few ninja moves ANASAZI gave me in case of revolt (yes, TrailWalkers have been tied to trees before), our skills aspire to be nothing fancy.

My job description is basically to be loving, see the good in others, and be ready to help, which sounds more like a Girl Scout than a professional, and more demanding than a set of skills, especially if you were kicked out of Girl Scouts, as I was. A TrailWalker’s skill is not specialized knowledge but acting in the face of not knowing. Responding thoughtfully and intuitively, physically and emotionally. I am woefully under-qualified, like everyone else. Thank god for group intelligence. Wilderness is in the business of utilizing inadequacy: through ours and the land’s shortcomings, ANASAZI realizes its mission of having people learn to live on the land with others. We all lack too much to not be together.

ANASAZI takes pride in its emphasis on day-to-day desert living. No contrived consequences, it says, no psychological games. Dirt is dirt is dirt. In the desert, team-building and self-reflective challenges are built-in. Yet, how did the the kids end up in the wilderness in the first place? Artifice. Lying parents. Mine told me we were taking a road trip to visit my grandma. Ha! A father recently told his son they were taking a ride in a hot-air balloon. (“So, let me get this straight: is there a balloon?” he asked, dizzyingly, a week out in the desert.) Contrivance and scheming are often the only way to get kids to the wilderness, and once there, we live a charmed survival existence: everyone is going to make it. We are not surviving, we are playing survival. And it is this subtle entanglement of artifice and nature that is, I think, so productive. Wilderness therapy is not bare-boned reality, nor cause and effect at its purest. It is somewhere between performance and real-life, a performance for real-life: Wandering in the wilderness for 40 days is, and long has been, role-playing.

***

We improvise and we impersonate. We imitate Indians. Survivalists. Hip pies. Sages. We dance and howl under the moon, hold fire ceremonies, build hothouses out of willow, and can’t resist chanting in them as the heat drips off our ochre-painted faces. We make moccasins and leather bags, use tools modeled after the ancients and sew with synthetic sinew. We use an invented group-speak, chock-full of romantic and tribal echoes. When I got home from ANASAZI as a teenager, I stopped shaving my legs or wearing a bra or using a bed. It was a performance of sorts. I was imitating what I had seen in my TrailWalkers, and I was acting out what I felt in myself—evolution—mighty and intangibly hairy. Yet the performance was one towards authenticity. Authenticity, that tertiary animal—it takes in others who have taken in others, mashes and mixes, incorporates part, and lets the rest pass through.

Our desert performance brings to mind Rumi’s words: “Appear as you are, be as you appear.” The sequence is confounding. There is no linear cause and effect, rather, the two clauses modify each other. The action is where the imperatives meet. Appear as you are, be as you appear. You can see the circle of seeming and becoming: as if is part of as is.

Fantasy is not always fooling yourself. It may amount to becoming yourself. As spontaneous and free as being who-you-are is, it is nothing if not proactive and retroactive. Besides, performance is a form of survival. It takes the edge off reality, which is quite sharp in the desert. “Acting like” creates a distance from ourselves that expands our possibilities. For instance, thinking like a stone can soften your steps, as The Seven Paths of the ANASAZI Way suggests:

I say this in all seriousness.

Don’t be offended at the stone that turns beneath

your feet. After all, the stone isn’t offended at you

even though you were the one who turned it.

That a stone could take offense at us is laughable, but then, maybe so is our anger when we trip over it. Impersonation opens us to the possibility of the impersonal, which is a particular interpretation and not the lack of one. An impersonal lens shows that you happen to the world as much as it happens to you—so don’t take head bumping so personally. We’re all playing here.

***

Even the plants are acting as if. They call it growing “adventitious roots.” These roots are root impersonators, and true eccentrics in the plant world. The desert is drowning in them. Almost 200 species of cacti have exclusively adventitious roots, which grow not from other roots, but from stem or leaf tissue, making them sprout in unusual but fruitful places. They are versatile role-players, and often inspired by stress. If you’re of an adventitious mind, stress lets the play begin. “If ‘existence’ is responded to as if it were less than totally in earnest,” wrote Lionel Trilling, “spirit is the less bound by it. It can then without sadness accept existence, and without resentment transact such business with it as is necessary.” Necessity is necessarily playful.

***

On top of the mountain, Rebecca chucks her pack into a crevice. It’s 120 degrees out. That there, that’s not me. James and I are squatted on stones that could cook our asses sunnyside up. Our sunny sides are get ting smoked, and our associations a bit scrambled. Scramble is a funny word, I say it over and over, as we fry on the rock with empty canteens. Can can can you do the can’t can’t can you… we haven’t moved from this spot in a couple hours. In a little while, I’ll be gone, the moment’s already passed, yeah it’s gone. We are in a rocky wash with no brush. Rebecca does not care to move towards shade or water. She does not care that without her pack she will have no food, no clothes, and no blanket tonight when it’s cold.

James is trying to use reason.

“How will you eat?”

“I’ll go into the Boys Band and take all their food.”

“How will you find them?”

“I’ll howl till they get scared and cry and I hear where they are.”

“How will you stay warm?”

“I’ll go into the Boys Band and rape them and steal their blankets.”

“Your plan is to rape the boys for warmth?”

I bite my finger not to crack a smile. After Rebecca elucidates her plan to kill us all with the knife she’s been too lazy to sharpen, we fall back into slumped staring. Jen and Marian are up ahead a ways, sharing some scrappy shade. I keep on with the song in my head. Emergency Radiohead for defibrillating detachment. I’m not here, I’m not here, this isn’t happening.

The question I always hear is, “Does it work?,” or its variant, “Does ANASAZI fix them?”—which sounds to me like a teen neutering, which meaning maybe isn’t so far off: Do the kids permanently stop doing what they shouldn’t? What is inconvenient to the parents? Do they stay sober? Do they quit cutting class? Are they nice to their mother? Do they stop hanging around those friends? According to these measurements, I was worse off after ANASAZI than before. Yet I consider myself a success story.

Often I’ll tell kids that I was a YoungWalker like them. I’ll also tell them that I came back four years later as a SinaguaWalker, that is, as a legal adult. What I never tell them is that, my second time in the program, I ran. And, contrary to the hopeless statistic I tell each group, I escaped ANASAZI. Why would I, who so loves the desert, run from it? Out of respect. The program does not modify behavior; it invites a way of being. That invitation, once internalized, never leaves. What more could the desert say to me? It was on me to choose to use or not use what had been given me. I ran, because I did not want to piss on sacred ground.

The wilderness does not make you change, but it does make you choose. Changes change, but choice is always there. This is why ANASAZI works even when it fails to fix.

Ok, but how does it work, parents insist. How does being outdoors heal people on the inside? The YoungWalkers share their doubts. They ask good questions: How is hiking around all day going to help me with my problems? Maddeningly and mysteriously the only answer to that is to keep hiking. I can’t say why pushing through brush or trudging dry creek bed, one minute inching under, then leaping long, scaling red ledges, edging along and behind and over and at times, in flushes of hot realization, in complete circles, help a person to think more clearly of themselves, others, and the world. I have to suspect that mystery is part of the efficacy. Daily doses of the incalculable are good for growing humans.

***

Flora and fauna come to resemble each other in the desert. Extreme constraints breed creative redundancies. Solitary bees and desert flowers have both adapted to live much of the time underground. They speak the same language. As soon as the warm rains hit, the bees and seeds erupt from their earthen dens. Following the beat, they pick up their natural conversation as if no time had passed at all. There had been much time, in fact, much solitude and invisibility. Absence organizes a sticky liquid flying buzzing blooming attuned hearty world around it.

Desert rain does not fall on deaf ears. Believe it: bees and toads and rodents and fleshy seeds listen in holes underground.

***

The Chinese sages believed the bland to be healthy for mind and body. Blandness is the celery of the aesthetic diet—it gives us a workout with its slightness. We find ourselves crunching hard on air, burning off more than we’re taking in. Understimulation, say the bland gurus, exercises the senses. Intensity leaves us with nothing to want, but boredom, boredom lingers. Intensively. What to do? You’ll just have to occupy yourself.

***

O the vapor of blandness! how it opens the spiritual sinuses.

Blandness, the interminable Mormon virtue. There is an oft-told story in Mormon circles that illustrates its high place in spiritual matters. Former President of the Church, Spencer W. Kimball, was once asked, “What do you do if you find yourself caught in a boring sacrament meeting?” The spiritual giant thought for a moment, then said, “I don’t know; I’ve never been in one.” Mormons know this to be a mightily ironic response because no one knows better than Mormons how boring they can be. The implication is that President Kimball was not simply hearing what there was to hear but generating something more. He who has ears to hear, let him hear something better than is said. Learning by the Spirit, as Mormons call it, means experiencing what is not present. It’s a promise that no blah-blah is endured in vain, for “he shall mount up in the imagination of his thoughts as upon eagles’ wings.” When one is tempted to write off longsome tiresome ho-hum tedium, one is to contemplate filling in the blank.

What’s in a Mormon Church, Temple, Desert, Get-together? Jazzed absence. Blandness takes the spike out of punch and puts it in your brain.

***

The sun’s down, but—high praises—so are we. Off the freaking mountain at last. Those of us who did not chuck our pack in a hole and leave it to rot, drop our stuff under our scraggly canopy of juniper. Jen and Marian waste no time in getting out fire sets and food. They down a handful of almonds and brown sugar lumps before setting to work on the fire. Rebecca eyes Jen’s opened sugar bag.

I’m too worn out to care about food. James hasn’t moved or spoken since we put down our packs. He sits hunched on the ground like a comatose toad. No sooner do we exhale, Wind comes upon us.

Wind is an exalted TrailWalker, a lone ranger. He or she roams free of any Band in order to help all Bands. Sometimes this is life-saving. Other times, Wind blowing through your camp can be totally deflating. Some Winds police as much as they doctor. Wind pops in, fresh and perky from his lone cowboy camp, energetically wins over our girls, making us look like sticks in the mud. Then tells us what we can do better. At those times, Wind is the grandparent of ANASAZI, rolling in, spoiling our kids, lending unasked advice, then leaving us to deal.

Our Wind is not the ranger you’d expect. He wears trousers and a sweater vest. He is small and impeccably cheery. His boyish look belies his experience, as does his use of obscure, old-fashioned swears, like “gosh-all-Potomac!” or “blistering barnacles!,” which is who he is on and off the job, but is also a persona he cultivates. Once, his first week out on the Trail, in freezing January, his pack got swept down the Verde River as he and the group struggled to cross. Some camper found it eventually and turned it over to the park rangers. From its clothing content, they thought some poor 80-year-old man had washed down the river. Wind was delighted to get his green sweater vest back.

“Howdydoo! Permission to enter camp?” Wind enters our circle and shows the kids his new papoose, gorgeously beaded and fringed. He sings a merry song before asking to powwow with the TrailWalkers. Me and James try to look alive as we follow him off a ways.

Wind tells us what we already know and can’t imagine.

“You have to hike back up and get that pack. And Rebecca has to choose to do it with you.”

The first part sounds unpleasant, the second unfathomable, and the two, at any rate, are at odds. Leaving the pack there isn’t an option, yet we must give Rebecca the option. ANASAZI’s emphasis on agency really ties our hands back. James and I laugh but Wind doesn’t. He doesn’t know Rebecca. No substance on earth could induce that girl to turn around and hike back up that mountain.

I have to eat my words. Wind and Rebecca have a private Sitting for an hour, and when they rejoin the group, Rebecca tells us she is ready to go. James and I are shocked, chastised. Why didn’t we have more faith in her “seed of greatness”? Wind has out-zenned us.

Halfway up the mountain Rebecca furtively takes a little baggie out of her pocket. A full Ziplock of glistening blue Tang. No one in our group could have such a stash. Genius. ANASAZI has its Ideals, but thank god even the exalted ones condescend to bribery.

***

As iconic as the American desert has become—all three-armed cactus and cow skull and moon-puckered coyote—the desert is the iconoclast of ecology. The very definition of desert is debated. Dry, hot, salty and barren. A desert may be all or none of these things. The Arctic has been called a polar desert, and the open sea—there are not many places wetter—oceanic desert. The root of desert means forsaken or abandoned. And this seems to be our measure of it: Desert is a place that is lacking. A place apparently empty, full of less obvious life.

Get a bunch of geographers in a room and they’ll mostly agree that deserts are defined by their aridity. However, ask how arid a region must be or how best to measure this aridity, and some rocks might fly. It is better, suggest some, to think of arid regions as a continuum of environments, measured in degrees rather than absolutes. The desert likely has no boundary.

It seems we are constantly crossing into other worlds as we hike: a morning of flat cracked earth, noon on a scruffy mountain, midday in a ponderosa forest carpeted with pine needles, and a canyon-deep evening along a rushing stream.

The desert’s continuum also runs vertical. Each landscape has another landscape underneath and waiting to pop up. I remember a day a few summers ago, I was in Girls Band, and we were trudging up a bone-dry creek bed. Everything was rock and gray. Almost all at once the air turned incredibly heavy as low clouds smothered the sky. We were rounding a mountain of black-charcoaled trees when the rain dumped. It pooled improbably, and greens seeped out of nowhere. The landscape was becoming fluid like a dream. What I’ll never forget: moon-white flowers unfurling like bat wings. They were everywhere, spooking at dark raindrops. They beamed pale against the burned-up trees, the sky’s boiling gray. There was something mammal-like about them that repulsed and enthralled. I don’t remember them having any purple, but I always think purplish-shade when I remember. Perhaps because it sounds vaguely poisonous. To this day I don’t know what these flowers are, and honestly, I’m not interested. They remain the plant of my dreams.

***

Brigham Young told his desert people in 1852: “Progress and improve upon and make beautiful everything around you. Cultivate the earth and cultivate your minds . . . make gardens, orchards and vineyards, and render the earth so pleasant that when you look upon your labors you may do so with pleasure, and that the angels may delight to come and visit your beautiful locations.” And so the desert became the ground of the Mormon imagination.

A non-Mormon visitor to Salt Lake City commented that Young seemed to fuse spiritual enlightenment and landscape building, preaching “exaltation in heaven” one Sunday, and the next, “how to irrigate and drain land, harvest crops, set out trees, beautify their grounds. . . .” Perceiving the potential of the desert became itself a religious practice.

Mormons were trained, spiritually and practically, to colonize wastelands. The Church sent out hundreds of groups of converts to establish Mormon oases across the wilderness: Eastern Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Arizona. My ancestors, converts came to Salt Lake from Scandinavia, were told to uproot once again and blaze their way to the dry, flat, empty heart of Arizona. They did, and they built, and they spread, leaving only briefly, once plural wives were outlawed in the U.S., for the Mexican side of nowhere, and when those houses got razed by revolutionaries and sunk back into the sun-baked mud, they returned to Arizona as if it were home all along.

Even today, any good Mormon will move in a heartbeat when asked to do so by the Church. Home, by these lights, is not where you live, but where you’re led. This is an old story of the wilderness.

***

Desert as a moral and social guide is not a breakthrough of modern psychology, new coat of “wilderness therapy” notwithstanding. Jesus and Muhammad spent significant time in deserts, and Moses, poor Moses, couldn’t lead his people any other way.

The story of Abraham begins without preamble: Get lost. Go forth from your native land, from your birthplace, and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you. Come undone in the desert. Leave every thing you were about to be for nothing you could say with any certainty. Become other, which is finally you.

Lekh lekha—literally, Go to yourself.

The Book of Mormon starts with a family commanded to leave iniquitous Jerusalem and enter the barren desert. They must uproot, reorient, begin again. The people carrying this book split from American society to set up their own State in the wilderness.

Intrinsic to desert is testing ground. It is where humans go to either escape from or conceal extreme corruption. The story across time/space: Man leaves behind the comfort and spoils of society and turns toward an indefinite integrity. He takes to the blank of the desert to reimagine what man is about. He writes. The words sink into dust. We who are made of dust take to translating it.

***

When I first started TrailWalking for ANASAZI, I wanted to be put with Boys Bands. They’re stronger, I concluded, lazily. They’ll be faster hikers, better fire-makers. Gradually I learned my mistake. Ask any TrailWalker who has been there and back with both groups, and they’ll tell you the same thing: The girls have the most endurance. This is the truth of my women ancestors crossing the desert with their homes tied up in wagons, children on their hips, the husband ahead or behind. I didn’t come to their stories until later. Women to me are the long run surprise.

One of the aims of the Mormon colonizing expeditions of the 1870s was to establish peaceful relationships with the Indians. This meant traveling through Navajo territory – tough, red land. White heat. Black winds. In our family history journals from this expedition I found the story of one of my foremothers giving birth on the rocky backbone between the Colorado and San Juan Rivers. When the family reached a plateau, a blizzard was raging, and exposed to the wild winds and snows, the woman went into labor. The husband tried to pitch a tent as she pushed. As the baby emerged a hard slapping wind came and blew the tent upward. The woman reached up and held the pole down with one hand, the baby, now, in the other.

The desert is full of holy tents full of holy men and holy smoke of manly meats for the man god behind the curtain. But when I hear the Lord dwelt in a tent, all I see inside is my foremother using her body as a stake as she pushes out human life.

***

Give any slob a compass and a machete and they’ll look all business. The desert is maybe the only place where the more rugged you look, the more professional you seem. With my pink tentacles of greasy hair, rainbow button-up shirt complete with duct tape patches, and pants with a wide smile of stitches across the ass—I look unimpeachable.

The truth is, I’m bad with maps. The problem is deeper than that: I am spatially handicapped. I always have been. I exist in a geographical blackout. It does not matter how long I stare, I cannot match a squiggle on the page to a ridge on the land to save my life, which is the point. I am a wilderness guide after all. What complicates matters even more is that I cannot locate the direction of sound. I have only one ear that hears. ANASAZI uses a hooting system—a very distinct yawp—to communicate and navigate within and between Bands. This can prove crucial if, say, the group gets split up for whatever reason and you must find one another in a vast and hairy landscape. You don’t want to go up the wrong mountain. Which is exactly what I have done. It’s shameful. Is that a hoot? Watch my good ear spin in circles to catch it. Like a dog chasing its nub of tail.

So how have I gotten this far? Moderate wits, fat luck, and, unfortunately for my group, endless trial and error. Fortunately for me, they don’t know that. Circles in a barren place are hard to recognize. The desert is discreet.

I have taken our group to the wrong cow tank, and it is dry, and we are out of water, like we have been since yesterday. Everyone is in bad shape. Barely speak. Wolf mouth, shut, keep moisture in, thoughts in small o smoke rings. W a t e r e s c a p e. We’ve stepped into delusional. We’ve dropped our packs on the cracked mudbank and are resting our aching backs of wasted wet against them. No one says anything. Rebecca picks up a rock and scratches big letters into the dry skin of her arm: S-E-X. Someone must have another idea.

***

Another ancestress of mine gave birth in a tent in the desert. She was a second wife. Part of an outlawed but covenant union. There is no heavenly hurt quite like a commanded threesome. Following the exodus from Mexico, the fugitive family stopped long enough for her to give birth to a son in a government tent. There, a few days later, she was abandoned by her husband, his other wife and their family, and left with a young daughter, a newborn, and a desert. She, and her children, never saw her husband again. She made the desert and solitude her home, refusing to move, refusing to remarry, calling it her life.

Stories repeat in the desert. Wives turn each other out, houses split, lines continue. Hagar weeps, God sees, wells appear, histories proliferate. And descendants plumb the depths.

It wasn’t until my grandma was an adult with her own family that she discovered her mother had been part of a polygamous household. The second wife had never been spoken of. As the secret cracked, bit by bit, correspondences opened between the families. It was found that the two wives, in their old age—husband long dead—had written letters. “As I look back over the years I think of those days we lived together. We were so closely associated and had trials and many things came up which could have been avoided if only we had been more patient and kind. . . . Eva dear, with all my heart and in deep humility I ask you to forgive me, that we may live in unity, love and happiness in the hereafter.” Sarah and Hagar never met again. But in the 1940s and ’50s they sent postcards across the desert between them.

In the desert, stories repeat until they change. Echoes bring the rockslide.

***

Blandness has no stake in any one thing.

Revelation and epiphany only cramp the bland’s style. Conclusions forgo it. It prefers the logic inherent in change itself. In the landscape of blandness, extremes express not themselves but each other: one state passing into another. States waving their own lack of allegiance.

The bland carries the world on the shrug of its shoulders. It lets itself be led from one extreme to another, with as little intervention as possible.

***

There should be water right—here. A sad empty bed, the color of old oyster meat, stares up at us from where the map showed a solid blue circle. This is not good, this is not good. This is not a mantra James and I say out loud.

“Ok guys, sit tight, I’m just gonna take the radio and go up on that hill to check in, alright?” My voice is a clip higher than usual.

James and I lock eyes for a second. He’s as much at a loss as I am. Even if he knew better, it is not the ANASAZI way to take the maps out of somebody’s hands, no matter how tenuous their grip. Efficiency is not our meat.

I know this. I know it’s about “experience,” but I don’t sense the great possibilities of failure when failure is sucking our bodies and brains dry. I’m charging too fast up the rocky cliff in my Chacos, radio in one hand, the other pumping and grasping at boulders, shredding my fingertips, the rocks and I mixing our grits. There’s no reason to kill myself, but it feels good. I feel guilty and useless. As if these girls weren’t struggling enough as it is. I can’t even get them to freaking water and the sun will go down and they’ll be miserable and angry and probably write blister ing letters home and then their parents will be on the defensive and a whole new spat of tit-for-tat will begin and no one’s hearts will heal or grades improve and the girls will drop out of high school with vague talk of a GED and deliver pizzas to the door of a life they almost had but lost to dehydration.

I am having my TrailWalker meltdown moment. Radios are for checking in, but we also use them as a device for taking off to fall apart in private. Long check-ins are understood. I am where the hill levels out, lying on my back, sharp stones digging between my ribs, and I am crying like a dehydrated drama queen with low blood sugar. When I turn my face there’s a cow staring at me. There are three or four up on this mound, probably looking for the same tank we were.

ANASAZI 101: You are not the healer. Agree as you might, there is always some sneaky part of you that tries anyway. This part dooms itself to an illusion: lack as shortcoming. Which is a shortage of imagination: failure as failure.

***

Wilderness doesn’t allow for guides, only followers. No person—whatever their age or expertise—is beyond growing pains. Everyone is learning their limits, and tripping past them.

A Mom came out for Family Camp—the two-day reunion on the Trail of child and parents—and pulled a ballistic kid stunt: She ran away. The desert drove her nuts. She tried to book it for a road, any goddamn road. A TrailWalker recently hopped in the emergency vehicle before the week’s end and refused to get out. Two months from now, dear James, according to his own Walking, will have an epic freakout, to be named The Vanishing, and will not return for six months.

Self-discovery is not a transcendent journey. It’s a private tantrum in a public place where you are both child and parent. The desert is space to let it all play out. With as little intervention as possible. Go on and kick and scream and cuss and throw that stupid pack down a hole and spit on it like you mean it. The desert won’t flinch. It only makes picking it back up unavoidable.

***

Sikong Tu, an illustrious poet of blandness, sang of a sweet spot somewhere between sterile and volatile. He wrote a cycle of poems to show what he called the twenty-four poetic modes. These poems have names like Harmony-Blandness, Force-Incipiency, Shimmer-Beauty, and the especially splendid Limpid-Sublime. Blandness plays between these poles. Unfixed, its balance can only be lost and regained, lost and regained, the hyphen a teeter-totter of attraction. Hyphens do interesting work. The meaning of each title exists not in the words but the relationship between them. With a single dash, content gets underwritten by chemistry.

Chemistry, that limpid-sublime stuff of live-wire I-thou encounter constantly threatened with obliteration. Martin Buber, whose I And Thou underlies much of ANASAZI philosophy, invented an opaque-lucid language to show, like Sikong Tu’s binomials, that our most basic units are relations. ANASAZI, in the hyphenate spirit of I-thou, has created its own language by pairing Buber and Navajo ideas. What Buber calls an I-thou relation, ANASAZI talks about as a Heart-at-peace. What Buber calls return, ANASAZI calls a New Beginning. Like the balance of blandness, a Heart-at-peace is transitory. It will lapse into seeing people as objects and objects as more than people. I once heard someone ask Ezekiel how it is then that you hold on to a Heart-at-peace. He said, you don’t. You keep getting one.

***

It’s midday, the day after we should be at Final D, and we break at a creek: sit our bums down in the sweet cool mud, soak our blistered feet, and James and I know our destination is just around the canyon’s corner. A mile and a half or so. So doable, so done. We did it. Damn we’re good.

We dry off some on the rocks then wriggle back into our packs and boots, ready. Hallelujah. The end is really here, when Rebecca up and chooses a different ending.

“I’m not moving.”

Girl down.

No one is sure how to take this. Downright senseless. Not that Rebecca has been a paragon of sense, but this move is so extravagantly backwards that I don’t even know how to bribe her. Rebecca wants to be at Final D, where she knows that she a) won’t have to hike for a few days, b) gets letters and FOOD and clean underwear, and c) can slap her yells off canyon walls like a little monkey in heat for all the boys camped at Final D to hear. She knows all this is a very short hike away. She knows she doesn’t like hiking in the dark, and she knows we need to leave now for that not to happen.

And yet, “I’m not moving.” Whether or not she knows what she means by it, she means it. We are not going anywhere.

After the first hour passes, Jen and Marian, patient, coaxing, even babying, move to dramatic, pleading, tearful, and after the second and third hour, threatening, sobbing, yelling, now sulking under the hot sun apart from Rebecca staked out under the one shade tree.

This is what ANASAZI calls a Heart-at-war. James and I move and moderate between the girls. I am calm and patient with Rebecca, but it’s no use because I am these things out of self-interest. The Heart-at war that smiles is just as useless as the one that kicks and screams. So I shut my mouth and close my eyes. Put myself in her place. Which is to say, I fumble around a 13-year-old girl’s brain until a crack opens and some grace slips in, and being Rebecca becomes real. My heart hurts and I can see her. And I see peace has to come from the other two girls.

Who are these girls? I go over to where they are sunk down and sullen on the dirt. We talk about a Heart-at-peace and what it means; I leave to fill my canteens; when I walk back Rebecca has her pack on and Jen and Marian are helping her tighten the straps using bandanas. I blink hard. These are astonishing humans. What on earth did the two girls say? How did Rebecca respond? Doesn’t matter. I feel it. The under-stated power I come back to the desert for.

***

When I returned home from ANASAZI as a girl, almost a woman, I remember seeing the desert as the meridian of my life. Me, my world, my relationships, divided into life before and after the wilderness. This would prove to be untrue. I would run from and return to the desert more times and in more ways than fit on two sides of a map. The meridian curved. Because, for starters, the desert is a cycle.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue