Articles/Essays – Volume 56, No. 1

Model Cars Are Not Cars (And Theories of Atonement Are Not Atonement)

If you mistake a model car for a real car, you’re going to have problems. I spent much of my life making that mistake in my thinking about atonement. I had read that “God’s justice requires that a penalty be paid for every sin”[1] and that “to atone is to suffer the penalty for sins, thereby removing the effects of sin from the repentant sinner and allowing him or her to be reconciled to God.”[2] I was in my mid-thirties when I discovered that this penal substitution idea is one of many different theories of what atonement is all about. Furthermore, there were well-developed criticisms of penal substitution theory—and they were good ones. I became desperate to find out what atonement really meant.

I’d like to write about what, for me, was a major step forward in this struggle: realizing that I’d been conflating models of atonement with atonement itself. Many readers may have separated those two things much earlier in life than I did, or even take that separation for granted, but for me it was a difficult paradigm to break out of. Even after I started studying theories of atonement, I treated them like competing descriptions of some historical event—like conflicting eyewitness accounts of a crime—when in fact they serve an entirely different purpose. Now I think of them as being something like scientific models of gravity.

Why Does a Dropped Stone Fall?

Aristotle proposed one of the first theories of what we now call gravity. He proposed that rocks fall downward when dropped because of their nature. After all, everything in the world was made up of four elements: earth, air, water, and fire. A rock, made of earth, is naturally attracted downward to the earth. Smoke, on the other hand, is attracted upward toward the celestial sphere because it is made of fire. This described people’s day-to-day experiences and was a perfectly good model for many years.

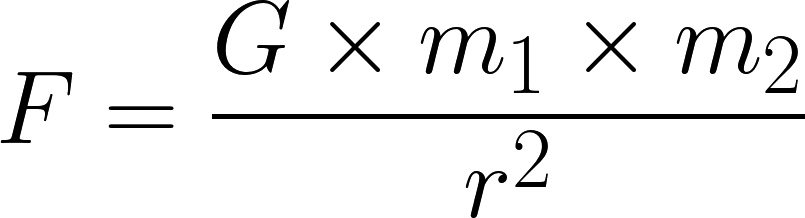

Many other models of gravity were proposed over subsequent millennia. In 1728, Sir Isaac Newton published the Principia, which envisioned gravity as an invisible force. His “law of universal gravitation” can be stated mathematically as follows:

In this equation, F is the force of gravitational attraction between two objects, m1 and m2 are the masses of those objects, r is the distance between them, and G is the “gravitational constant”—a multiplier that causes the units of measurement to work out nicely. This model explained why all kinds of objects move the way they do—including the six then-known planets, whose orbits had been charted by Kepler about seventy years earlier.

Let’s pause for a moment to notice something important: Newton’s model describes (mathematically) how gravity behaves. What its effects are. But it doesn’t really tell us what gravity is or why it exists in the first place. Models like this are useful because they state more or less simply how some aspect of the universe behaves and even predict its behavior in new situations. For example, Newton’s model was used to predict the existence and location of Neptune after astronomers noticed irregularities in Uranus’s orbit. However, these models don’t necessarily reveal any deeper truth about the phenomena they describe.

Newton’s laws were (and are) highly influential. But eventually, scientists started noticing things that Newtonian physics couldn’t explain, like the peculiar orbit of the newly discovered planet Mercury. Physicists searched for new models to explain these phenomena, and Albert Einstein finally succeeded with his theories of relativity. There have been additional developments since Einstein, and there will certainly be more in the future.

Models as Abstractions of, and Substitutes For, Reality

So . . . seriously, why does a dropped stone fall? Which of the various gravitational theories is correct? The answer is probably “none of them.” Models are simplifications of reality that abstract away detail and complexity in order to highlight a particular feature. We may choose to use particular models depending on what feature interests us, but we should never expect the model to correspond to reality otherwise. Statistician George Box put it succinctly: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”[3] A model car is not a car, but is useful because it gives a sense of the car’s design and style. Newton’s gravitational model is not gravity, but we can use it to put satellites into orbit. And theories of atonement highlight various features of our relationship to Christ—but they are not atonement.

So the interesting question is not “Which model is correct?” but rather “Which model is useful to me?” For example, I didn’t learn relativity when I went through engineering school. I learned the older Newtonian physics. Einstein’s models more accurately describe the world, but Newton’s models are close enough for engineering situations and are much easier to learn and use. The simpler model is more practically useful for my work.

A useful model becomes a substitute, a stand-in, for reality itself. I might define gravity by saying, “Gravity is a force that attracts two objects together. Larger or closer objects incur stronger gravitational force.” But I’m really describing Newton’s model of gravity. I have no idea what gravity really is. So, we understand reality through our models—they mediate reality for us. This is a normal part of the human experience, and it works great if you and I both realize that the model we’re discussing is not reality itself.

Problems can arise, however, if we start to confuse the model with reality. If you try to believe that a model car is actually a car, you’re going to have problems.

Models of Atonement

Like gravity, atonement has been understood through an evolution of different models. The one that seems to be in official use by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is penal substitution theory. The Church’s Preach My Gospel manual describes this model by stating, “Justice is [an] unchanging law that brings . . . penalties for disobedience,” and that Jesus “stood in our place and suffered the penalty for our sins. This act is called the Atonement of Jesus Christ.”[4] Because of that last sentence and many other statements like it, I thought for many years that penal substitution was atonement. But this is only one model of many.

Critics of the penal substitution model find it easy to create caricatures, like this one from J. Clair Batty:

Children sent to the hen house gather eggs and accidently, carelessly, or deliberately drop the basket and break the eggs. These children have been conditioned to expect a terrible beating for their transgression. An older brother comes along and seeing the plight of the poor trembling egg-breakers says something like this: Although I have never broken an egg or spilt a drop of milk in my entire life, I, the strongest, will take the beating you so richly deserve. I will take upon my shoulders the responsibility for your broken eggs. I will suffer for you, after which you will be in my debt forever and ever.

This scenario presupposes an authority figure who could be deceived into believing that big brother actually broke the eggs or who was so befuddled, frustrated, drunken, or angry that it didn’t really matter who broke the eggs just so long as he could vent his rage by inflicting pain and seeing someone suffer.[5]

Of course, the point of this caricature is to illustrate the inconsistency of trying to satisfy justice with an injustice—namely, punishing the innocent Jesus in place of the guilty. Alma 34:11–12 seems to speak directly to this point by stating that a just law wouldn’t be satisfied with penal substitution, and therefore only “an infinite atonement will suffice for the sins of the world.” A pro–penal substitution interpretation of this verse might put the emphasis on the word “infinite,” submitting that human justice can’t accept penal substitution, but God’s infinite justice transcends humans’ and makes penal substitution work in a way we can’t understand (the “incomprehensibility” claim, which I will revisit shortly). A critic’s interpretation, on the other hand, might put the emphasis on the word “atonement”: penal substitution can’t satisfy justice—period—and therefore atonement is needed instead. The critic’s reading of Alma 34 separates penal substitution from atonement, while the adherent’s reading merges them.

I was surprised to learn that the penal substitution model is largely a product of the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation and an adaptation of a more generic eleventh-century model called satisfaction theory, which claims that our sins have offended God’s sense of righteousness and honor. In this model, Jesus’ suffering makes restitution for our offense—not by suffering an incurred penalty per se but by paying an honor debt in a way characteristic of medieval feudal societies. Satisfaction theory is still a substitutionary model and is just as easy to caricature (see J. Clair Batty’s Sunstone article for a great example).[6]

I then wondered: if penal substitution is a Reformation-era improvement on an eleventh-century satisfaction model, what model did people use before that? To be fair, some supporters of penal substitution try to trace its origins backward from the reformers to Augustine in the fifth century, Cyril of Jerusalem in the fourth, and Clement of Rome in the first, thus attributing it to some of the early church fathers.[7] But there seems to be more general agreement that substitutionary ideas were unknown in the early church and that the ransom theory of atonement was used instead. According to ransom theory, our sins give Satan a claim on our souls. This claim is legitimate (i.e., God recognizes it too), and so God, in the form of Jesus, offers to trade his soul for ours. Satan accepts and waives his claim on us, but after seeing that death cannot hold Jesus, realizes he has been tricked and left with no prize at all. This is the model portrayed in C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Critics tend to object to the amount of power Satan seems to have in this scenario, or to the idea of Christ tricking and deceiving in this way.

There are many more models out there, but by now I was in crisis mode. Voltaire famously said that no problem can withstand the assault of sustained thinking; it seemed that no theory of atonement can either. After much searching, I finally found the conclusion: they’re all just models. They’re all wrong. Or, to say the same thing in a more generous way, they’re all perfectly good models.

Penal Substitution in the Doctrine and Covenants?

Many of the biblical passages we associate with atonement do not explicitly describe penal substitution. We tend to impose a substitutionary interpretation on them. Interestingly, it takes much less effort to see penal substitution in the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants. One of the strongest passages is Doctrine and Covenants 19:13–20, in which Christ tells Joseph Smith that he (Christ) has “suffered for all, that they might not suffer if they repent.”

However, in the passage immediately preceding this one, something very interesting has happened. The text says, “It is not written that there shall be no end to torment, but it is written ‘endless torment.’ Again, it is written ‘eternal damnation.’ . . . I am endless, and the punishment which is given from my hand is endless punishment, for Endless is my name. Wherefore—Eternal punishment is God’s punishment. Endless punishment is God’s punishment” (D&C 19:6–12). So, according to these verses, the term “endless punishment” actually means God’s punishment, not (as literally every English speaker would have thought) punishment that goes on forever. In this case, God doesn’t mind the misinterpretation because, “it is more express . . . that it might work upon the hearts of the children of men, altogether for my name’s glory” (D&C 19:7).

So inaccurate models are perfectly acceptable to God if they work—if they achieve a desired effect “upon the hearts of the children of men.” This makes perfect sense: the usefulness of a model—its fitness for a particular purpose—always matters more than its correctness. In Doctrine and Covenants 1:24, God acknowledges that he is happy to communicate using models himself: “these commandments . . . were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding.” What is “the manner of our language” if not the set of symbols, metaphors, and models that we use to communicate and mediate spiritual concepts? In other words, God uses rhetoric. Immediately after sharing this “mystery” with Joseph Smith, Christ employs the substitutionary language in verses 13–20, with which Joseph Smith would have been very familiar.

Separating Model from Modeled

There is something to be said for keeping models of things separate from the things themselves. Consider the Aristotelian model of the cosmos. This model put Earth at the center of the universe, with the sun, moon, and all other heavenly bodies revolving around it. And why not? This model explained people’s day-to-day experience. In fact, it matches our day-to-day experience so well that we still use this model whenever we talk about the sun “rising” and “setting.” However, the Aristotelian model wasn’t always acknowledged to be a model. In Galileo’s time, it was seen as objective fact. This caused serious problems for Galileo, who supported Copernicus’s heliocentric model of Earth revolving around the sun. A 1616 Roman Inquisition found heliocentrism to be “formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture,”[8] and Galileo was later sentenced to life under house arrest. Keeping models separate from reality is important because it allows us to adjust and improve the model when we encounter its limitations, like astronomical observations giving rise to heliocentrism, or Mercury’s orbit prompting a change to Newtonian physics.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints seems to completely identify penal substitution with atonement. We have a unique gift for making “the transcendent literal and the mundane heavenly,” as Richard Bushman puts it,[9] and so we find it easy to think about atonement in terms of prison sentences, cash transactions, or other images from the mundane, objective world. But once we bring atonement into the mundane, objective world, it needs to be explained. And when the (substitutionary) explanation fails under the assault of sustained thinking, our only recourse is to claim that atonement cannot really be explained after all. Take for example James E. Talmage’s statement that, “in some manner . . . to man incomprehensible, the Savior took upon Himself the burden of the sins of [hu]mankind,”[10] which simultaneously asserts substitutionary atonement and (thanks to the adjective “incomprehensible”) also preemptively rejects any requests for explanation.

So, to sum up, we conflate the penal substitution model with atonement, we then conclude that atonement is incomprehensible because penal substitution is, and the believer is left to accept a substitutionary atonement while being told they can’t understand it. To be clear, I have no problem with calling atonement incomprehensible, or with accepting things I don’t currently understand. It’s just the feeling that we claim incomprehensibility simply to avoid thinking things through, when some good reflection might lead to new models that can “work upon the hearts of the children of men” in new ways.

In the meantime, accepting penal substitution saddles us with penal substitution’s limitations, illustrated previously by J. Clair Batty. If penal substitution were accepted as merely a model, these problems could be easily dismissed as shortcomings of the model. We could simply admit, “Yes, the model breaks down there. The substitutionary model beautifully illustrates Christ’s willingness to suffer the pain of this human world we’ve created in order to improve it. But to say that God literally demands violent suffering for every sin is to take the analogy too far.” However, if penal substitution is not a model—if it’s identified with atonement itself—we’re stuck with its limitations.

In the end, I’m not sure atonement belongs in the objective world at all. It might instead belong in the world of love, forgiveness, redemption, symbol, myth, and adventure. We can let atonement live in that world. If we acknowledge that atonement theories are just mediating models but let them affect us anyway, then the whole thing works. Then ransom theory is a moving story about Christ’s daring rescue mission to save the world from sin. Then penal substitution theory is a moving story that illustrates Christ’s willingness to accept and understand the evil of our world in order to transform it. And both are effective. To see oneself as the hero of these stories—like we do when we watch a good movie—is now to see oneself as Christ. The whole experience becomes meaningful and essential. Atonement is about being reconciled with the divine—including the divine in each person. It’s about being at peace (at-one) with life. Life is great and terrible. It’s the coexistence of opposites: light and darkness, health and sickness, pleasure and pain. Atonement is knowing all this and choosing life anyway. What symbols or models do you adopt to help you redeem life and humanity in this way?

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Church Educational System, Doctrines of the Gospel: Student Manual (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1986).

[2] “Atonement of Jesus Christ,” accessed Apr. 19, 2022.

[3] G. E. P. Box, “Robustness in the Strategy of Scientific Model Building,” in Robustness in Statistics, edited by Robert L. Launer and Graham N. Wilkinson (New York: Academic Press, 1979), 201–36.

[4] Preach My Gospel: A Guide to Missionary Service (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2019), accessed Apr. 19, 2022.

[5] J. Clair Batty, “The Atonement: Do Traditional Explanations Make Sense?,” Sunstone 8 (1983): 11–16.

[6] Batty, “The Atonement.”

[7] Derek Tidball, David Hilborn, and Justin Thacker, eds., The Atonement Debate: Papers from the London Symposium on the Theology of Atonement (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan Academic, 2008).

[8] Maurice A. Finocchiaro, ed. and trans., The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 146.

[9] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 477.

[10] James Talmage, Jesus the Christ: A Study of the Messiah and His Mission (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1915; repr. 2018), 558.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue