Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 1

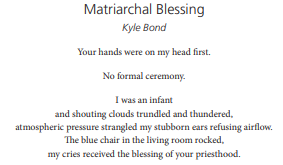

Matriarchal Blessing

Your hands were on my head first.

No formal ceremony.

I was an infant

and shouting clouds trundled and thundered,

atmospheric pressure strangled my stubborn ears refusing airflow.

The blue chair in the living room rocked,

my cries received the blessing of your priesthood.

I was initiated.

Your family was my first ordained tribe.

Still, the anchor and chain slung over my back

are your lessons, to me, about the meaning of Zion:

memories of your collectivism.

We walked

each Christmas

together to the hospital,

like the Israelites to Canaan

with an offering of chocolate for the sick:

trimming 40 years

from Individualism’s priestcraft

and capital’s oblivion

with your sugar sweet vision.

I ran

up and down fields

with you watching from the sidelines;

your blessing meant your time,

your attention, your trophy of importance.

I returned

home a different man

and you asked, “What did they do to you?”

I tried to tell you, but I think you knew

because you saw me hurt

and you hurt:

you lost me.

I had lost myself.

And then I lost you.

Though you are gone,

it is your blessing that remains within me.

All others are only external.

The nine

—φημί—

it is your voice that my memory resurrects

when the syncline canyon breathes on my face

—ψυχή—

and the ghosts of my salience swirl

—γίγνομαι—

as did the sea when the spirit of God moved on the face of the waters

—ποίηση—

like Red-shouldered Hawks spiraling above the pine-laced crags

of Timpanogos’ Prominent

and the snake’s ribbons in the dirt of Provo’s Canyons.

Οὖν ὑμεῖς τέλειοι—

yet not final.

You return

in these images,

with the lessons you sang:

before you formed me in the belly you knew me;

to be an egalitarian is to know God,

of whom I am only a part.

You showed

receipts on those holidays

in the same spirit of your blessing,

making sure we knew that at least in your eyes

we mattered

alike

by the labor of your hands and the sweat of your brow.

With you, covenants were an unspoken spiritual contract

for the wellbeing of the broken,

laced with the strength of compassionate indignation.

You warred

when our neighbor came over dressed in frantic burning tears

telling us that her son was locked in the bathroom

and the water was filling

and she didn’t know what to do.

You didn’t ask questions

or

follow procedures

or

cast judgements—

you flew over the fence,

kicked in the basement window

and pulled him to safety

just before his head went under.

Mother, again, rejoined with child.

That was what mattered.

Never mind the puddle of blood you were standing in,

a three-inch laceration on your ankle,

which you refused to be treated,

though you had a sister as a nurse,

and a hospital in your backyard.

Instead, you superglued it shut yourself.

. . .superglued. . .

The scar, a silent evidence of your blessing’s meaning—

that a single, even vulnerable life

is worth saving,

and for that, scars are worth having.

Years later,

in meditation,

your blessing is slowly teaching me something long forgotten:

there is no such thing as being worthy.

There is only being.

And worth.

Because, to talk about worthiness means placing value on others,

and value is not ours to place,

only to foster.

In this blessing,

like the Judgement of Solomon,

it wouldn’t have mattered if our neighbor was your enemy;

you would have still saved her child,

because he too was your child.

You’d have taken her scar;

not because he was a child,

but because within the paradox of not placing value

it was people whom you counted—that counted.

Simply put, Zion could only be built again on the altar of sacrifice.

You understood this.

But, within my slow crystallizations of your understanding, I am forced to wonder

if it was actually Eve who built the altar where Adam prayed.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue