Articles/Essays – Volume 40, No. 3

Latter-day Saints under Siege: The Unique Experience of Nicaraguan Mormons

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

The LDS Church is currently gaining many new members in Asia, Africa, and especially Latin America. Nowadays more than 35 percent of the worldwide membership is concentrated in Latin America, compared to about 45 percent in the United States and Canada. By 2020, the majority of Mormons in the world will be Latin Americans, if the current growth rates continue. Judging from current LDS growth rates, the future Mormon heartland will be the Andes and Central America, instead of the Wasatch Front. Rodney Stark is exaggerating, however, when he labels Mormonism the next world religion, since he ignores a drop-out rate for converts that generally exceeds 50 percent. One year after joining the LDS Church, only about half of the new converts remain active, meaning that they attend Church services at least once a month.

Latin America contains more than one-third of the worldwide LDS membership, but the members are not equally divided among the nineteen countries. (See Table 1). Numerically, the Mormon Church in Latin America is currently strongest in Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Honduras (and Central America as a whole), Peru, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic. In all of these countries, between 1 and 3 percent of the population have been baptized into the LDS Church. Active Mormons, who go to Church at least once a month, make up at best about half of the baptized members. Core members, those who pay their tithing and follow the LDS code of conduct, usually form about half of the active members.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1: LDS Membership in Latin America at Year-End 2005, see PDF below, p. 135]

To assess in which countries the Mormon Church is growing, a look at the recent average annual growth rates (AAGR) is necessary. (See Table 1.) Membership growth currently seems to be stagnating (at best 2 to 3 percent a year) in almost all Central American countries but Nicaragua, including Guatemala and Costa Rica (they experienced strong growth in the 1980s), and in Chile, Uruguay, Colombia, and Puerto Rico. To explain this stagnation would require a separate country-by-country analysis, which is not feasible here. In Puerto Rico, for instance, immigration to the United States is probably an important factor. Moreover, most people who were open to experimenting with Mormonism have probably done so by now in many of these countries.

However, the situation in other Latin American countries is radically different. Based on the average annual growth rates for 2003–04 and 2004–05 in Table 1, the LDS Church is currently experiencing its strongest membership increases in Brazil, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay, and especially Nicaragua, which is all the more reason to take an in-depth look at the distinctive experience of Mormons in Nicaragua.

The main thesis of this article is that Mormon growth in Nicaragua is directly influenced by the country’s turbulent political context. But how did historical and political developments affect LDS growth? To ad dress this question, I first give an overview of my data and methods. A short introduction to Nicaragua is followed by information on the various churches in Nicaragua. Subsequent sections deal with the early history of the LDS Church, the occupation of LDS Church buildings, the underground LDS Church in the Sandinista era (1982–90), the reestablishment of the LDS Church in 1991, and the LDS growth explosion in the 1990s. I conclude with a short summary and some tentative projections.

Data and Methods

The principal source of information here is my fieldwork in Managua, Nicaragua, in 2005 and 2006. I studied competition for members among the Catholic Church (especially the Catholic Charismatic Renewal or CCR), various Pentecostal and neo-Pentecostal churches, and the Mormon Church. I engaged in participant observation in these churches in two low-income neighborhoods: barrio Monseñor Lezcano in west Managua and barrio Bello Horizonte in the east. I also interviewed various Church leaders, members, and missionaries, and conducted a literature study.

My research project is part of an international program, which is studying global Pentecostalism on four continents. Its central concepts are interreligious competition, religious markets, conversion careers, and the culture politics of churches. All research projects use standardized checklists for the interviews and participant observations. This “conversion careers” approach includes a typology, which distinguishes five levels of religious participation: disaffiliation, pre-affiliation, affiliation, conversion, and confession. In all four continents, interviews are conducted with members corresponding to each of these five categories.

My findings here all come from the Lezcano Ward, which shared the building with the Las Palmas Ward, whose members came from another poor neighborhood in west Managua. The Lezcano Ward officially had 260 members in 2005, but only about 120 of these were active (46 percent). The bishop reported that church attendance on Sunday was generally about 120, but I usually counted 60 to 80 people. On February 6, 2005, for instance, there were 58 people, about two-thirds of whom were women and girls.

The Lezcano Ward was served by two pairs of missionaries, each pair consisting of one North American and one Latin American missionary. The North Americans were almost all from Utah, Idaho, or California. The Latinos came overwhelmingly from other Central American countries like Costa Rica, Honduras, and Guatemala. The missionaries were aware that Church growth in Nicaragua was strong at the time: Most could expect to baptize at least ten people during their two-year missions. But the missionaries generally knew next to nothing about the country and its tragic history.

An Introduction to Nicaragua

Nicaragua has more than 5.5 million inhabitants and is the largest in physical size of the Central American republics. The country’s major problems are political instability, bad governance, state corruption, an extremely skewed income distribution (severe inequality), and especially massive and extreme poverty: 78 percent of the Nicaraguan population lives on less than US$2 a day. One terrible consequence is that one-fifth of all children under age five are undernourished. According to official statistics, about one-third of Nicaraguans are illiterate.

How did this situation develop in Nicaragua? The key factors are corrupt elites and foreign interventions. The U.S. Marines intervened in Nicaragua almost continuously between 1909 and 1933. President Franklin D. Roosevelt avoided direct military intervention and influenced Nicara guan politics through the commander of the newly trained National Guard, Anastasio Somoza García (1896–1956). Somoza assassinated guerrilla leader Augusto Sandino in 1933 and became president in 1936. The Somoza dynasty soon dominated not only politics, but also the economy. It ruled Nicaragua as its private plantation and ruthlessly repressed all opposition.

These circumstances led to the founding in 1961 of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN: Frente Sandinista de la Liberación Nacional). Somoza’s appropriation of most of the international aid after the December 1972 Managua earthquake caused national and international outrage. Somoza stepped up the repression, resulting in more popularity and support for the FSLN—even among the middle classes. Somoza’s old alliance with the conservative Catholic Church was weakening under the new Archbishop, Obando y Bravo. The FSLN intensified its revolutionary activities and finally defeated the National Guard on July 19, 1979. The Sandinista Revolution was complete, and Somoza and his family fled.

Nicaragua was in ruins in 1979. More than 50,000 people were dead, and more than 150,000 lived in exile. Many Sandinista leaders called themselves comandantes (commanders) and enthusiastically started working on a new society. The FSLN soon founded the Sandinista Defense Committees (CDS), which organized people at neighborhood level but also reported on “anti-revolutionary activities.” However, the FSLN was made up of many factions: Marxists, Maoists, social-democrats, Catholic and Protestant progressives (mostly liberation theologians and base community members), and middle-class liberals. The FSLN enjoyed huge support from progressives in western Europe and the United States but faced increasing opposition from the new Reagan administration.

The Reagan administration organized and supported the Contras: counter-revolutionary guerrillas, who were sometimes ex-National Guardsmen. In March 1982, the Contras blew up several bridges and launched violent attacks on peasants, literacy brigades, and the Sandinista People’s Army. Reagan also imposed an economic boycott and ordered the mining of several Nicaraguan harbors. The economic boycott decimated exports, forced increasing dependence on Cuba and the East Bloc, and led to hyperinflation in the mid-1980s. The FSLN government reinstituted compulsory military service in 1983. War and hyperinflation made life harsh.

The war, poverty, hyperinflation, and especially the compulsory military service led to the surprise victory of Doña Violeta Barrios de Chamorro in the November 1990 elections. She was the wife of Joaquín Chamorro, former opposition leader and owner of the La Prensa newspaper, who had been murdered in 1978 at Somoza’s orders. Although without political experience, Doña Violeta seemed the best person to achieve national reconciliation and end the war through improved relationships with the United States. Her government was followed by two neo-liberal governments. President Arnoldo Alemán (1996–2002) was sentenced to jail in 2003 over corruption charges involving millions of dollars. His successor, neo-liberal president Enrique Bolaños served a shortened term (2002–06). Then Daniel Ortega, still firmly in control of the FSLN, won a surprise victory in the January 2007 elections. The government is currently dealing with heavy pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) because of its huge external debt: more than US$4 billion in 2005.

The Churches in Nicaragua

In the 1980s, the relationship between the FSLN and the Catholic Church hierarchy gradually became tenser. The Bishops’ Conference became increasingly critical of the FSLN government in its 1981–83 pastoral letters. Priests with government functions, like the Cardenal brothers, were threatened by the hierarchy with sanctions and often expelled from their Church offices. The conflict was essentially a political power struggle over control of Catholic believers. On the one side, progressive Catholics (base communities, left-wing intellectuals, priests, friars, and lay leaders) sympathized with the FSLN and wanted to help it in their fight for a more just society. On the other side, the conservative Church hierarchy wanted to control its progressive priests and keep them subject to Church authority. They were driven by a deep distrust of the Sandinistas’ left-wing ideas and by the hierarchy’s traditional alliances with the middle and upper classes. Above all, the hierarchy wanted to avoid divisions within the Catholic Church. With the support of the new pope, John Paul II, they gradually but successfully started to marginalize sympathizers of the Sandinistas within the Roman Catholic Church. Their method of disciplining priests and expelling lay leaders was effective, but at the cost of what they wanted to avoid: increasing divisions within the Catholic Church.

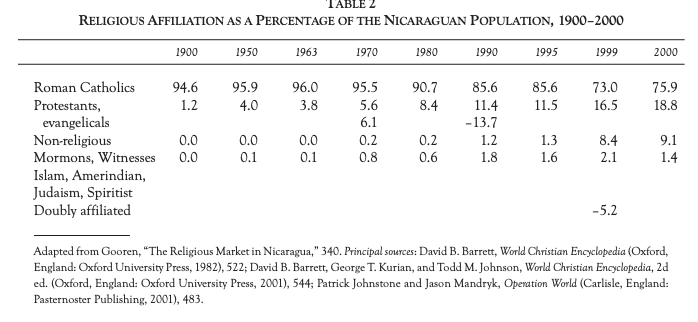

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2: Religious Affiliations as a Percentage of the Nicaraguan Population, 1900–2000, see PDF below, p. 140]

Cooling relationships with the Catholic Church caused the FSLN to seek legitimacy with the progressive sector of Protestantism. The Protestant organization CEPAD had been organized after the 1972 earthquake and become involved with the Sandinista governments. The more conservative Protestant sectors, represented especially by Pentecostal leaders, founded new organizations like CNPEN in 1981 and the Evangelical Alliance in 1990. Pentecostal churches in Nicaragua seen strong growth during the anomie of the 1980s.

Catholicism was Nicaragua’s official religion until the constitutional reforms of 1894 and 1907, which introduced full freedom of religious exercise. In 1963, no less than 96 percent of the population considered itself Roman Catholic. In 2000, however, the percentage decreased remarkably, to almost 76 percent. (See Table 2.) During the same period, the percentage of Protestants went correspondingly, from 4 to almost 19 percent. There are currently approximately 3.85 million Roman Catholics in Nicaragua, an estimated 1 million Protestants, and more than 50,000 Latter-day Saints.

A Short History of the LDS Church in Nicaragua

The first two missionaries of the LDS Church arrived in Nicaragua in 1953, less than one year after the founding of the Central America Mission in Guatemala City on November 16, 1952. The LDS Church was already present in neighboring Costa Rica since 1946 and in Honduras since 1952. Like elsewhere in Central America, growth in Nicaragua was slow in the first decade. The first Nicaraguan was baptized on April 11, 1954. The Nicaragua District of the Central America Mission was organized in 1959.

The 1950s and 1960s were characterized by local Church-building—by the foundation and consolidation of branches and wards. The Church always made an effort to maintain smooth relations with the Somoza family to ensure the freedom to proselytize. The oldest LDS Church buildings in Managua, dating from the mid-1960s, include the Lezcano Ward meetinghouse and the meetinghouse in the east Managua barrio Bello Horizonte. Nicaragua now has two missions, but (as yet) no LDS temple. Members have been going to the Guatemala City Temple since 1984.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 3: LDS Membership in Nicaragua, 1953-2005 at Year Ends, see PDF below, p. 146]

Church growth remained slow in Nicaragua for a long time. (See Table 3.) By the end of 1979, right after the Sandinista Revolution, there were 3,346 Mormon members. One year later, membership dropped by almost 30 percent, resulting in 2,406 members by the end of 1980. Throughout the 1980s, membership statistics fluctuated significantly. To explain why this happened, a closer look at the Sandinista decade is necessary.

The Occupation of LDS Church Buildings, 1982–90

David Stoll, a U.S. anthropologist, describes in detail the confiscation of various non-Catholic Church buildings by Sandinista activists in 1982. I will compare Stoll’s information to two interviews I conducted with Mormon informants who had direct experience in the events of that era.

Stoll places the occupations against the background of the participation of “two dozen Moravian pastors” in the military rebellion of Miskito Indians against the FSLN government in the Caribbean coastal provinces. On March 3 and 5, the Sandinista newspaper Barricada published articles denouncing “The Invasion of the Sects.” Later in March 1982, the Contras blew up two bridges in the north and the Contra war started.

Without providing evidence to support his claim, FSLN comandante Luis Carrión declared on July 16, 1982: “An enormous quantity of ex-National Guardsmen are now evangelical pastors.” Comandante Tomás Borge denounced Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Seventh-day Adventists for allegedly receiving funds from the CIA. “As Sandinista rhetoric escalated, churches were vandalized and their members threatened by mobs.” On July 22, Barricada reported that Sandinista Defense Committees (CDS) had occupied three buildings belonging to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Church of God, and the Assemblies of God in the low-income neighborhood Ciudad Sandino. After mediation from CEPAD, the Protestant organization sympathetic to the FSLN, these buildings were returned within a few days.

But on August 9, 1982, Sandinista Defense Committees seized more than twenty Adventist, Mormon, and Jehovah’s Witness buildings in various Managua neighborhoods. The FSLN leadership claimed that these seizures were spontaneous reactions by the people to the “theological backwardness of the groups in question. But the truth seems to have been otherwise,” comments Stoll. “CDS barrio chiefs and neighbors, some of them embarrassed by the seizures, told evangelicals that the order had come from above, apparently CDS commander Leticia Herrera, who worked next to one of the choicest buildings seized.”

The occupation was also an anti-American reaction to the increasing hostility of the Reagan administration toward the Sandinistas. In line with Borge’s accusations, Adventists, Witnesses, and Mormons were singled out as American churches with CIA connections. During these months, some North American missionaries were harassed by mobs in downtown Managua. Brian Hiltscher, a returned LDS missionary, told this story to a U.S. newspaper: “We saw a large banner off in the distance on the front of a cathedral, with the letters of the major revolutionary group in bold red. Soon a mob of 50 appeared, and they began to walk towards us. With bottles and rocks in hand they began to chant, ‘Death to the Yankees.’ Their yelling was directed right at us, but all we could do was walk through them. I guess you can say that missionaries have an undying faith. The Lord is just with you all the time. We went home that day without a scratch on our bodies.”

The pro-Sandinista Protestant organization CEPAD noted that even the FSLN leadership had a hard time distinguishing between non-Catholic groups that supported the revolution and those that did not. “Three of the six Mormon churches seized were returned that same year, plus a fourth much later.” The two remaining buildings were returned after the Sandinistas lost power to President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro in 1991. One of these was the meetinghouse of the Lezcano and Las Palmas wards that I studied in barrio Las Palmas, west Managua.

I will compare Stoll’s data to the stories of two well-informed Nicara guan informants, Daniel and Gabriela, who are both ex-Sandinistas. Gabriela (age fifty-four) goes to church in the barrio Batahola Norte, where she lives. In 2005, she was president of the Family History Center of the Lezcano Nicaragua Stake. The center had four large microfilm machines, two smaller ones, and two computers with an internet connection. However, Nicaragua is the only country in Latin America where the Roman Catholic Church has not yet permitted the Mormon Church to put birth and marriage records on microfilm.

Gabriela’s parents were among the first Nicaraguans to join the Mormon Church in 1954. She was baptized at age ten in 1961. In the 1970s, she became a militant in the FSLN. After the revolution, she visited France, Hungary, East Germany, and West Germany as president of a Sandinista youth organization. She never had any problems with the higher FSLN leaders over her membership in the Mormon Church. They were always very tolerant, she said. The problems began, however, when she started working with the lower FSLN ranks. She became disillusioned and left the FSLN in 1987. Gabriela mentions that many other disillusioned Sandinistas joined the Mormon Church after 1990: politicians, group leaders, the military, etc. Contradicting Stoll and Daniel (below), she says that the Lezcano meetinghouse was only briefly occupied in the early 1980s. According to Gabriela, this action was taken because some local FSLN leaders were badly informed, but the situation was quickly sorted out.

Daniel was bishop of the Lezcano Ward for eight years, which is not uncommon in Central America. Born in mountainous Estelí on May 8, 1961, he joined the LDS Church in 1988 at age twenty-six. At that time, he was working in Managua as a taxi driver by day and studying at night at the university. He grew up in a family that was “neither poor nor rich.” When he was a child, various relatives took him to visit their churches: Catholic, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pentecostal. He didn’t like any of them, seeing much hypocrisy. At nine, he didn’t want to go to any church any more. He occasionally got into fights at school and on the streets.

By the time he was twelve, he became even more rebellious. He ran away from his Estelí home after he was “brainwashed” at school by FSLN instructors talking about “the oppression of the people” by Somoza’s brutal dictatorship and was a Sandinista guerrilla fighter for many years. Various times he barely escaped death when farmers would tell him to leave their house because the Guardia Nacional was coming. Many times bullets passed close to him. He was caught by Somoza’s National Guard and beaten, though not tortured, but his father managed to obtain his release. Afterward he was religious and a Christian, though still not a member of any church. The first time the Mormon missionaries came knocking at his door, he sent them away angrily. But the second time his heart had changed entirely. He received all the discussions (charlas) and soon got baptized.

Daniel was already completely disillusioned with the Sandinistas around 1985, when he saw that they were beginning to break their promises of democracy and freedom. They became corrupt and reinstated compulsory military service during the Contra war. FSLN militants also occupied LDS Church buildings. The LDS building in San Judás, a very poor neighborhood in the south of Managua, was vandalized and damaged so seriously it had to be demolished and rebuilt. The Lezcano Ward meeting house became a military base for the Sandinista People’s Army (Ejército Popular Sandinista). The buildings were returned only after the elections of 1990, badly damaged and stripped of furniture. The fierce persecution of the LDS Church by the Sandinista government proved to him that it was the only true Church. Only the true Church would be the target of such aggressive state persecution. Just like the LDS missionary who confronted an angry mob (see above), Daniel placed the persecution firmly within a religious framework.

Gabriela’s memory seemed more selective than Daniel’s, who corroborated Stoll’s data. Gabriela hinted at divisions in the FSLN: The leaders were more tolerant of religious diversity than the lower ranks. She also mentioned that many Sandinista leaders eventually became Mormons in the 1990s. Daniel illustrated another process: State persecution may lead to increased commitment among the persecuted religious minority. This is essentially what happened when the LDS Church in Nicaragua went underground for almost ten years.

The Underground LDS Church, 1982–90

The Mormon missionaries, mostly of North American origin, were all withdrawn from Nicaragua in 1982, but Latin American missionaries were almost always present, according to Daniel. During all this turmoil, the number of registered Mormon members decreased from 3,270 in 1983 to 3,124 in 1985 and to an absolute low of 2,326 by 1989. (See Table 3.) This means that, between 1982 and 1989, 29 percent of all baptized Mormons in Nicaragua officially left the Church or were dropped from membership. From August 1982 until January 1991, the Mormon Church in Nicaragua effectively functioned underground. The Church decided to change its four wards into branches, making a total of thirteen branches. Since there is no literature on this period, I rely on Daniel, the former Lezcano Ward bishop.

This is what Daniel told me: “We met in secret in the homes of some members. These were called the núcleos (core, center). We always met in the house of members. It was very hard at this time, but the Church went ahead, because it’s the Church of the Lord. . . . We didn’t meet very often. There weren’t many of us.” He remembers that there were so few Melchizedek Priesthood holders left in the Church that the missionaries had to perform blessings and preside over the underground núcleo meetings in members’ houses until the late 1980s. Daniel often accompanied them, because their dress code and their appearance in pairs made them very conspicuous in the poor neighborhoods of Managua. He had to take them to the members’ homes, too, because the missionaries invariably had trouble finding the locations.

Between 1982 and 1990, most members were afraid to tell co-workers or relatives that they were Mormons. Mormons in Nicaragua were effectively under siege from their own government. In the process, only the most committed core members remained. All the other members, active and inactive, put their LDS identity on hold or took on membership in another church. It was only after President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro came to power in January 1991, after surprisingly winning the November 1990 elections, that state harassment of the Mormon Church in Nicaragua ended and the North American missionaries could return.

Reestablishment of the LDS Church

After Doña Violeta was sworn in as president in January 1991, there was a huge reshuffling of government and bureaucracy positions at all levels of the state. The Chamorro government (1991–96) started a new era of church-state relations, particularly with regard to the Roman Catholic Church. Doña Violeta was an active Catholic, and several of her ministers were orthodox Catholics with ties to Opus Dei. The Catholic Church received various favors and state subsidies.

The persecution and isolation of the Mormon Church came to an immediate end in January 1991. The LDS Church was reestablished officially. Its members and missionaries were free to proselytize again, as they had been before 1979 during the Somoza regime. The first North American missionaries were reassigned to Nicaragua in mid-1991 and all meetinghouses were returned to the LDS Church. Many had been sacked, vandalized, and damaged. One or two had to be rebuilt entirely; all others had to be remodeled.

Daniel mentions that the meetinghouse in which the Lezcano and Las Palmas wards met, originally constructed in 1965, was remodeled in a matter of days around 1992. A second and much more comprehensive remodeling took place in 2002. All floors, walls, and roofs were changed, and everything was painted anew. The building now looks brand new and is well-maintained. The same goes for the basketball court. Neighborhood youngsters are welcome to come and play basketball with their Mormon friends. Youngsters use the court almost every night.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 4: Analytical Framework for LDS Church Growth in Nicaragua, see PDF below, p. 148]

Daniel remembers that people in the poor Las Palmas and Lezcano neighborhoods remained very hostile to Mormons for a long time in the 1990s when he was bishop. They regularly threw stones through the meetinghouse windows. Thieves from a nearby slum often broke in and stole things. Relationships with the neighborhood dwellers improved only after the LDS Church became involved in relief efforts after hurricanes Joan (1988) and especially Mitch (1998). Since then, relationships with the municipality of Managua and with the national government have also been excellent. LDS buildings are often used for organizing big neighborhood meetings. The current positive image of Mormons is reflected in the growth explosion the Church has experienced since 1990.

A Belated LDS Growth Explosion, 1990–Present

Four main LDS growth periods can be distinguished in Nicaragua since 1953. (See Table 3.)

1. 1953–65: no membership data available

2. 1966–80: strongly fluctuating growth, AAGR between -28 and +48 percent

3. 1981–89: decrease, AAGR generally around –3 percent (between –35 and +14 percent)

4. 1990–present: high growth, AAGR generally around 13 percent (between 7 and 25 percent).

I will analyze the chronology of LDS growth in Nicaragua according to the internal and external factors outlined in Table 4, taking into account both religious and nonreligious elements.

Unfortunately, no membership data are available for 1953–65, except those for the entire Central America Mission, which included Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Combined membership in these five countries went from 367 in 1953 to 9,873 in 1965. Costa Rica, Honduras, and Nicaragua together had 4,272 members in 1965.

During the second period, 1966–80, LDS growth fluctuated strongly. The main growth factor was nonreligious and external: social, political, and pyschological anomie. The city of Managua was growing quickly. Because of the war between Somoza’s National Guard and the FSLN guerrillas, the missionaries were periodically withdrawn from Nicaragua. Competition with other churches, especially the Pentecostals, increased in the 1970s. The 1972 earthquake killed more than 10,000 people and left more than 50,000 homeless, greatly increasing anomie.

I have discussed above the third period (1981–89), which was characterized by a decrease in LDS membership. The country was still at war and still in turmoil. All families suffered the impact of mandatory military service. Inflation and poverty skyrocketed. Nicaraguans continued to suffer intensely from social, political, and political anomie. During the 1980s, membership in the Pentecostal churches skyrocketed. Pentecostals successfully competed with and outbaptized Mormons. The appeal of the LDS organization decreased because of government harassment and the confiscation of LDS Church buildings. These events made the social costs of LDS membership very high. The LDS Church was forced to go underground and lost almost one-third of its members. All U.S. missionaries were barred from entering the country from 1982 until 1990, making the LDS missionary force much smaller.

As soon as government harassment ended with the transition to the neo-liberal government of Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, the LDS Church regained a strong appeal with Nicaraguans in the fourth period (1990-present). The former government harassment became part of the unique local experience and history of Mormons in Nicaragua. It had increased the commitment of the members who remained faithful to the Church. The previous Sandinista harassment now made the Mormon Church more popular, as becoming a Mormon could be construed as an act of rebellion against the FSLN. Hence, many disillusioned FSLN militants were baptized during this period. At the same time, becoming a Mormon also showed a rejection of the interference of Cardinal Obando y Bravo and the Roman Catholic Church in national politics. The anomie factor remained high because of poverty and political instability. The LDS missionaries were again permitted to enter and proselytize freely, another important growth factor. Moreover, competition with the Pentecostals was less fierce, as the Pentecostal growth rates were slowly decreasing in the 1990s.

Conclusion

How did historical and political developments in Nicaragua affect LDS growth? The LDS Church was forced to maintain good relations with the Somoza dynasty to ensure that its missionary force would not be hindered. As the war between Somoza’s National Guard and the FSLN guerrillas culminated in the late 1970s, LDS growth went up. When the Sandinistas took over in 1979 and gradually started to harass the LDS Church and its members, growth went down dramatically. Almost one-third of all registered members left, but the commitment among those who remained was strengthened by the persecution (as witnessed by Daniel’s story). The LDS Church was under siege from the government and was forced to go underground from 1982 until 1990. Many disillusioned Sandinista militants found in the apolitical LDS Church a new purpose and a chance to use their leadership capacities.

When the FSLN was surprisingly ousted in the 1990 elections, the LDS Church was formally reestablished and the North American missionaries could work unhindered. Various factors coincided to produce the LDS membership explosion of the 1990s: an end to state persecution, increased commitment among the remaining LDS members, the growth of the missionary force, growing dissatisfaction among Nicaraguans with “politicized” Catholicism, and a decrease in the competition with Pentecostalism. Like elsewhere in Latin America, the Mormon Church was popular because of its efficient organization which radiated success and middle-class values, its solemn style of worship and hymns, its lay priesthood, its strict rules of conduct, its practical teachings, and its unique doctrines stressing eternal spiritual progress.

But the LDS growth explosion in Nicaragua came at a price—the same price paid earlier in Guatemala and Costa Rica. The weak local LDS organization and leadership could not cope with the sudden influx of new members. Various strains and conflicts resulted from such cultural patterns as machismo. The net result was that at least half of the new converts became inactive within a year after joining the Mormon Church. Among the active Mormons, again only about 50 percent became “core” members who consistently attended Church services, performed their callings, paid their tithes, and followed the Word of Wisdom. This difference sheds new light on Rodney Stark’s high estimate of 267 million Mor mons (or his low estimate of 64 million) by the year 2080. Stark is simply projecting the high growth rates into the future, ignoring both the eventual decrease in growth after five to ten years and the high inactivity rate of at least 50 percent.

It is important to stress that the period of explosive growth in Nicaragua for Mormonism immediately followed that of Pentecostal explosive growth in the 1980s. A similar phenomenon happened in Guatemala, where the Pentecostal explosion took place between 1976 and 1982 and the Mormon explosion followed in the late 1980s. Although the situation was obviously different from one country to the other, the timing hints at a relationship between LDS and Pentecostal growth. Elsewhere I contrasted the more rational, intellectual appeal of Mormonism with the more emotional and experiential appeal of Pentecostalism. Since most converts to Pentecostalism used to be nominal Catholics, I hypothesize that joining the Mormon Church is probably easier for former Pentecostals than for former Catholics. Pentecostals are also more successful in mobilizing their entire membership to act as missionaries to bring in new converts. I showed above that fierce competition with Pentecostals slowed LDS growth in Nicaragua, while decreased Pentecostal competition led to increased LDS growth (as happened in the 1990s). The Mormon missionaries also arrived in massive numbers in the 1990s, coinciding with the LDS boom in Nicaragua. This finding confirms that of various scholars that the most important factor influencing LDS growth is the size of the missionary force. Finally, I speculate that the religious market always functions with a certain time lag. People may need some time to become used to new religious options, before they are willing to try them out. This intriguing relationship between the timing of Pentecostal and Mormon growth obviously requires further study.

It is highly tempting to speculate about the future of the LDS Church in Nicaragua and elsewhere in Latin America. In 2006, there were already seven LDS stakes in Nicaragua, up from four only three years earlier. I expect that, in the coming years, the construction of a small temple in Managua will be announced. If Nicaragua follows the growth patterns of Guatemala and Costa Rica, then in five to ten years its average annual growth rates will also decrease to about 2 percent a year. The LDS Church seems to concentrate its missionaries in countries where the prospects for growth are best. If this policy is continued, Nicaragua may still be among these countries for another five to ten years. Afterwards, a higher percentage of missionaries will probably go to countries like Paraguay, Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, and later perhaps to future growth markets like Colombia and Venezuela. This article has shown that internal wars or anti-American governments in Latin American countries will at best only delay LDS growth. When the war in Colombia ends at last and Hugo Chávez marches out of his office in Venezuela, the LDS growth rates in both countries are likely to increase as part of a catching-up process like Nicaragua’s in the 1990s.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue