Articles/Essays – Volume 53, No. 3

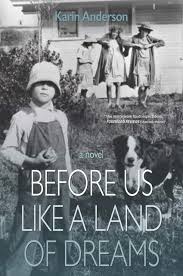

Karen Anderson’s Excavation of Ghosts Karin Anderson. Before Us Like a Land of Dreams

Mark 5:9—“My name is Legion: for we are many”—opens Karin Anderson’s masterwork Before Us Like a Land of Dreams. Anderson lyrically pools her ancestral narrative in sweeping loops, eddying history, religion, and landscape. Ghosts speak elusive, needling “truths.” Homesteads are temples of their own. The narrator is excavated as artifact—the individual is not individual, the collective not merely alive.

This excavation occurs through pilgrimage, both automotive and digital. Anderson and her narrator bleed together in the drives to sun-drenched towns and sun-stripped cemeteries, tracing genealogical roots and mining journals, maps, and microfiche newspaper archives. There is urgency. This truly is a pilgrimage, a dusty highway where the narratives explored are not relics but reliquaries. They hold the holy: communion with the self via the embedded many.

Guided by the Catholic Saint Ignatius, the narrator steps into pivotal and poignant moments of her own intangible history. At a graveyard, many years before she will be born, the narrator confronts her stranger-grandfather: “How much is unforgivable? I saw you—the ghost of you—in my father’s worst moments. I don’t know how to forgive him. I don’t know that I should” (69).

Another ghost, a grandmother, admonishes the narrator: “And you can’t let go what you must hold. This is a sin. The kind you still believe in” (71).

If forgiveness is a more violent form of consignation, which I suspect, then it is to this novel’s credit that it is far too sage for half-strung easy condolences. Instead, this novel is a performance of empathy. In prose all talon and yellow eye, no forgiveness is found, but each ancestral—and ancestral-adjacent—ghost is given their voice.

Sometimes they speak over each other or against each other. Some accuse. Some grieve. There are horrors and beauties. Gravestones pepper their tales, as they pepper ours. Ghosts are carefully revealed to be un-whole, a fragment constructed from shared flashpaper memory. One ghost rails against another ghost’s glib documentation of him: “In the end that’s what I, Olaf Larson, was remembered for in Fremont County, Idaho. Not the last jar of pickled onions in my dead wife’s sitting, not the lousy farming nor even the huckleberries or the Victrola. Not even for the hundreds of stereoscopic images of a brief world loved and lost. It was my love for Leon Wheelwright” (154).

These encounters draw attention to the unknown, the displaced, and the denied. The connection between the titular “land of dreams” and the dream of the American West and its Manifest Destiny is unmistakable; so is Anderson’s subversion as she depicts its reckoning. Within the great American West, Anderson frames the perspectives absent from normative family histories seeking to establish, well, the constructed norm. You will recognize these voices as the cavernous absences in annals of the West and Pioneer Day narratives. Indigenous peoples and queer people step into their stories.

Guided by Ignatius, the narrator—also denied, also displaced in a patriarchal, heteronormative narrative—reflects on the events and family that compelled this journey. A mother, a son, a writer’s block, and then in the compressed layers, a father with no latitude for queer children; the first blinking understanding of 1960s racial politics; the clawing scrabble for language to communicate and connect, and its inevitable, bewildering failures. Anderson writes, “Why Be is an unanswerable question, and so I tend to stop asking for a while and feel better. Eighty or so years on a planet like this one is such a puny interval it usually seems reasonable—even sweet—to see it through. . . . I’m generally satisfied to believe we exist to watch sunlight strike Permian planes. But I was driving south in a chokehold of personal crisis so maybe I wasn’t myself” (13).

“Why Be” reframes into “Why Was.” It informs the narrator’s research, but it also informs her catalogue of herself: why was that anger toward male effeminacy carried from her father’s people to her father? Why was it that that form of violence stopped with herself? “Do you think that stuff stays in us, even sideways?” the narrator asks (201). “What say you,” Ignatius repeats (202).

Later, the speaker mourns both the absence of the narratives and their presence (for if they exist, so does the distilled “sideways stuff”—relic and reliquary): “Do we even exist—did we ever exist—if the stories, even the imperfect ones, even the fragments, dissipate with the tellers?” (290).

The response, not the answer, is adjacent to the title of this novel, a line from Matthew Arnold’s poem, “Dover Beach”: “for the world, which seems / To lie before us like a land of dreams, / So various, so beautiful, so new, / Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, / Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; / And we are here as on a darkling plain” (28). As though through a glass darkly, between life and the shredding death, there is no certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain, even in—especially in—bearing witness to it.

Slinging through the Coronado Trail through the White Mountains, after encountering generations of ghosts, witnessing and then leaving the contoured geography of the family body, the narrator comes to a rest. There is no reconciliation, but perhaps there is recognition—and we as readers, ever mindful of the litheness of our own ghosts, feel their legion.

Karin Anderson. Before Us Like a Land of Dreams. Salt Lake City: Torrey House Press, 2019. 375 pp. Paper: $18.95. ISBN: 978-1-948814-03-4.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue