Articles/Essays – Volume 56, No. 1

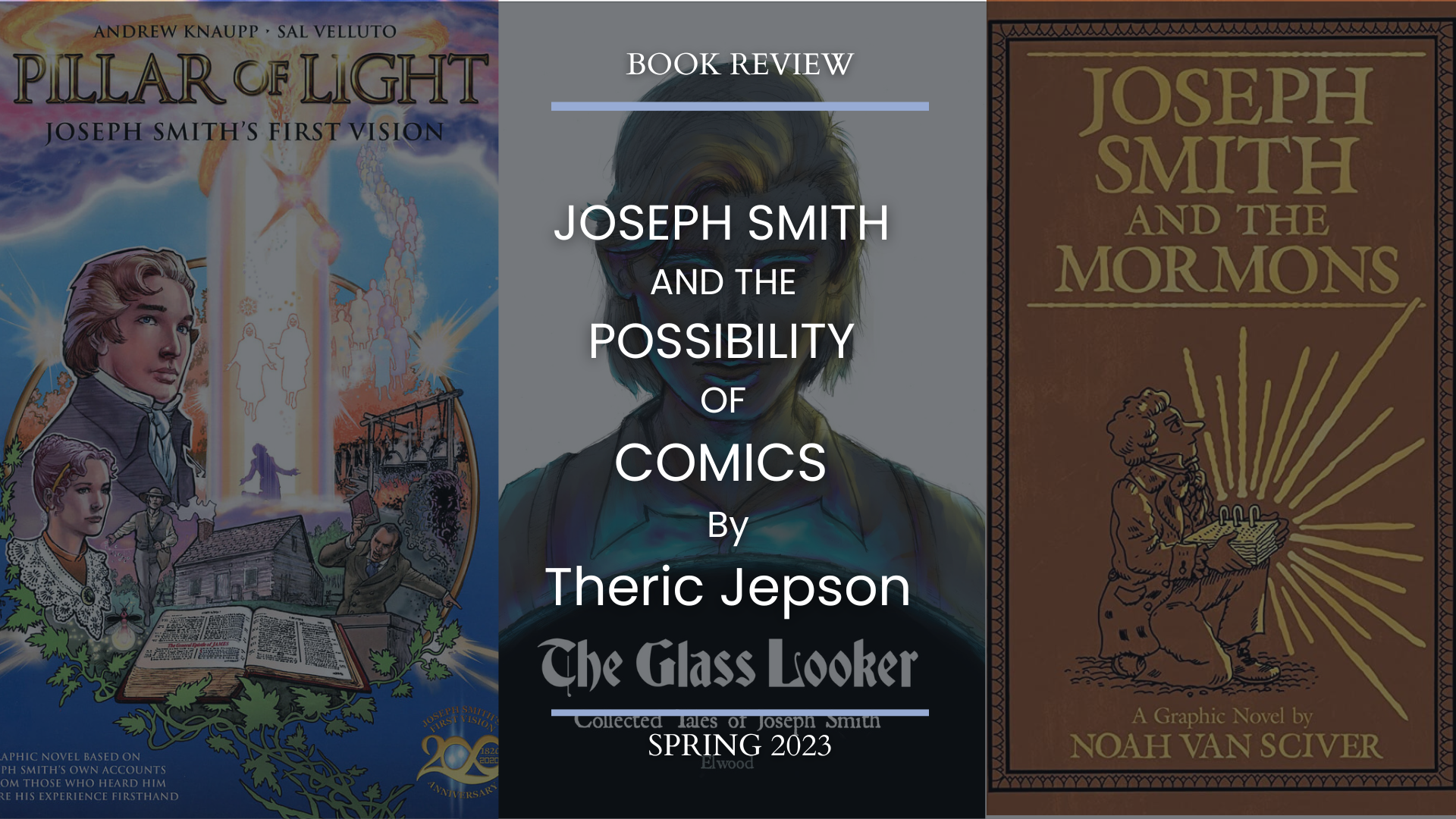

Joseph Smith and the Possibility of Comics Andrew Knaupp and Sal Velluto, Pillar of Light Mark Elwood, The Glass Looker Noah Van Sciver, Joseph Smith and the Mormons

Renaissance scholar Ada Palmer estimates we know 1 percent of what happened five hundred years ago and that two-thirds of what we know is wrong. I have no reason to doubt her expertise—and every reason to suppose that the numbers aren’t that much better when we consider two hundred years ago.

All the scuttlebutt the last couple decades over the “real” details surrounding Joseph Smith—whether his polygamy, treasure-hunting, translating with a stone, whatever—has weakened Church members’ collective confidence in a once solid-seeming story. But while new information may lead to bewilderment or even crises of testimony, realizing how little we know also opens room for new narrative possibilities.

Since 2020, three significant new approaches to the Joseph Smith story have been undertaken in comics, each successfully breaking a path through the gnarled forest of known history. In short, Pillar of Light, written by Andrew Knaupp and drawn by Sal Velluto, takes varied versions of one event and correlates them into one clear whole. In The Glass Looker, Mark Elwood does not attempt to smooth together the prophet’s early life but presents each version of the boy Joseph as a series of sometimes contradictory vignettes. And Noah Van Sciver’s long-awaited Joseph Smith and the Mormons builds the epic story of the man’s prime years to a coherent but complicated wholeness. All three of these graphic novels engage in the task of turning Joseph Smith’s complex history into a “true” story. They use diverse tools and present conclusions of varying ambiguity with distinct amounts of the personal, but they all are addressing who this man was and what he means now.

Let’s take them in publication order.

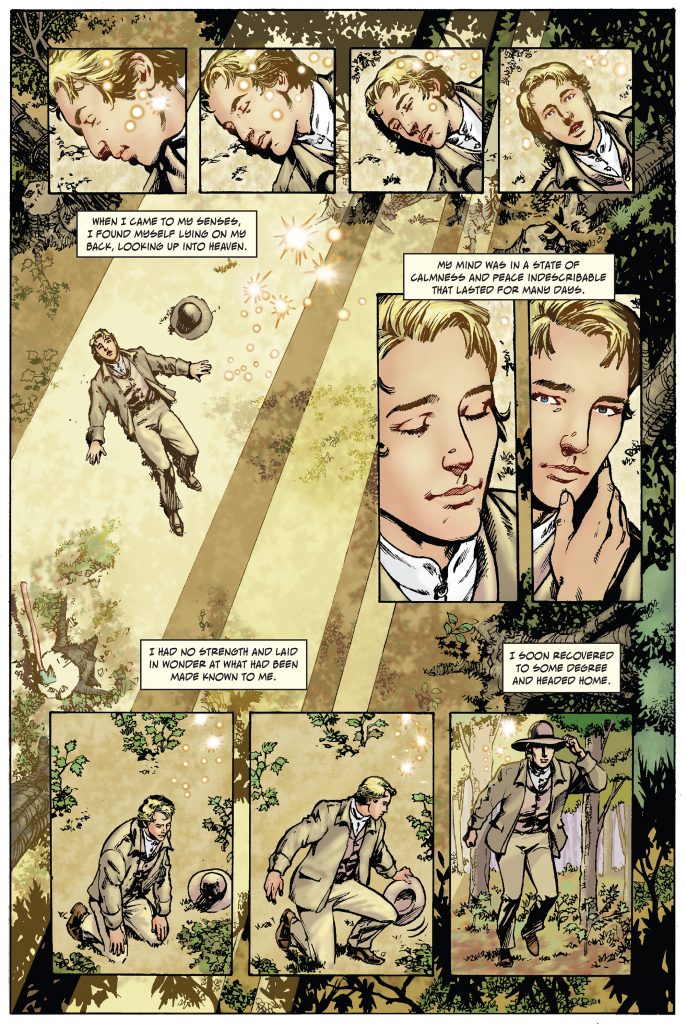

Arriving in time for the Church’s two-hundred-year anniversary celebration of the First Vision, Pillar of Light is the most traditional of the three volumes in several respects. Artist Sal Velluto is perhaps best known for his work on Marvel’s Black Panther, and the various gigs he has taken over the years largely showcase his knack with superheroes. For years, he made a comic for the Friend magazine about early Church history, and perhaps some readers of Pillar of Light will recognize that work and appreciate the familiarity.

Knaupp has labored to bring together each known telling of the First Vision credibly tied to Joseph Smith (he counts four) and combine their seeming contradictions into a straightforward narration. Why? Well, as Knaupp and Velluto state in their introduction,

Critics . . . have claimed that the differences . . . amount to contradictions and are evidence Joseph fabricated the story. We wanted to demonstrate that when you combine all the accounts, the result is a rich, consistent and synergistic narrative.

Pillar of Light has been carefully researched and includes details not previously shown in films and art, as well as accurate historical depictions, beautiful symbolism, and creative representations. We hope it is inspiring. . . .

We believe our Heavenly Father and His Son Jesus Christ have a message they want to give to the world. We are grateful to be a part of helping to deliver that message.

To summarize, their goal is akin to the goals of midcentury correlation in the Church. The mess we’re in now is often blamed on correlation, but when you start from the standpoint of faith, there must be a way to correlate the different views of history. Somehow this garden hose and this curtain must make an elephant! Frankly, it’s a noble goal and executed with professional competence in Pillars of Light. The only “negative” thing I have to say[1] is that this goal is not comics-first. As the BYU professor–penned foreword begins, “I don’t usually read graphic novels.” Exactly. This book’s audience is not first for those who love the medium but for those who are looking for a message delivered.

Commercially, this approach has plenty of upside. Most children’s picture books, for instance, are purchased by well-meaning adults trying to improve a child—not the child themself. And the creators’ intentions are pure—you can download the e-book for free. They really are trying to make the world a better place. And Pillar of Light is a step above much so-called correlated work we’ve seen in the past.

The risk, of course, is the risk that always follows correlation. By lauding their work’s value because of its “accurate historical depictions,” it can be easy for its audience—especially children—to not realize that Joseph’s “many angels” might not have included Moses and a Nephite record-keeper. I’m reminded of the stories common among Gen X and millennial Latter-day Saints about telling a Primary teacher “That’s not what happened” because, say, it was different in a Living Scriptures video. This sort of thing shouldn’t shake one’s testimony, but you can find people on Reddit who say it has.

This is not me trying to persuade you not to pick up Pillar of Light. Have it around your house! I’m just reminding you that you can’t exactly “Train up a child in the way he should go” with a comic book for Christmas. But the creators recognize this, and their sources are quoted in the endnotes so no one is stopping you (or your child) from judging the quality of the adaptation’s choices for yourself.

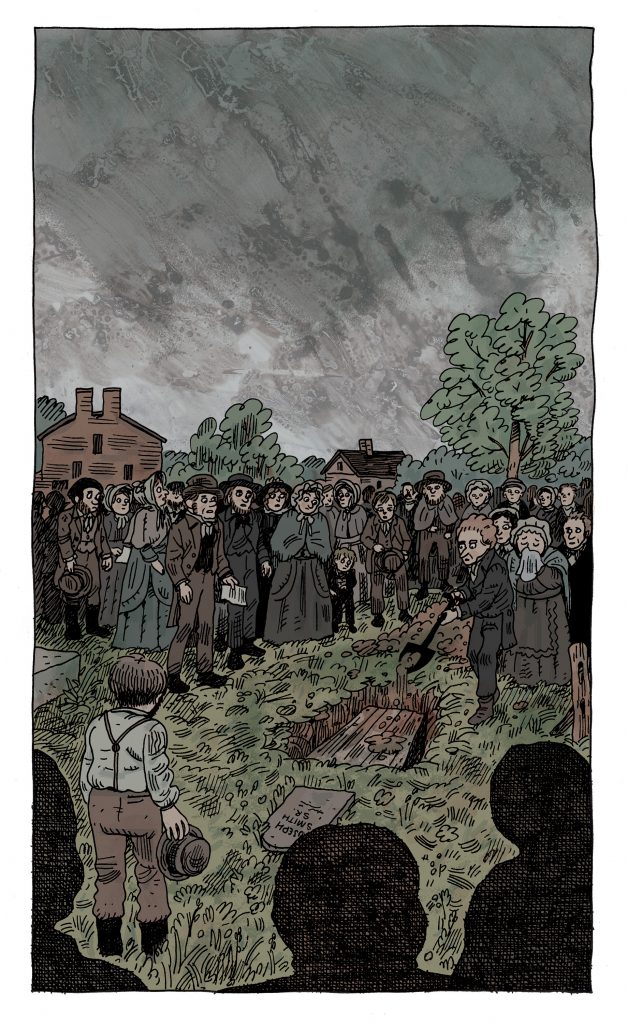

No one will confuse The Glass Looker with something out of the Church Office Building. This is as much an anthology of tales as a graphic novel, each story a facet of Joseph Smith lore. In one he is a mighty lad and in another a weak cripple. He may be a hard worker or a lazy bum, a spiritual giant or a cheap charlatan. These are the stories history provides, and Elwood gives each its telling. Perhaps ironically, this book also follows the Gerald Lund tradition; each story is followed by notes—and not just notes but direct quotations from period documents. The effect of these piled-up stories is both striking and humbling. I’m no historian, but I do fancy myself more aware of these stories than the average Latter-day Saint—and yet Elwood, by translating them into comics, has brought them to life. I’ve never given Sally Chase a lick of thought, but now I find her stone-seeing riveting. And nothing reminds a body that the past is an alien world like watching normal New England townsfolk out sacrificing a rooster in the hunt for treasure. The fiction of D. J. Butler has never seemed so close to reality.

Elwood’s art style is of the sort that leaves the pencils visible. I don’t always love that choice, and I don’t love it here as it gives his art a slightly amateur vibe, but by the end of volume one, the art had won me over. For a comic to work, the art must work—it can’t be all words and research. The marriage of art and word makes comics comics. I look forward to watching Elwood’s art refine in coming volumes.

Noah Van Sciver’s Joseph Smith and the Mormons is just as heavily researched as the other two books, but the research is not this comics’ raison d’être—it is a tool, not the goal. Van Sciver has been exploring Joseph Smith for well over a decade; early takes appeared in his BLAMMO! comic and Sunstone. When he portrayed the First Vision—almost as a horror story—in BLAMMO! no. 7 (2011), he included this near-apology:

While preparing to publish . . . I thought a lot about not including all the Joseph Smith stuff. In a way I feel embarrassed about it. I was indeed raised in the Church of the Latter day Saints [sic] until my parents divorced and I went with my mother who had had enough of the Mormon housewife role she had been playing. I was then taught that everything I had been brought up with in the religion was a lie. . . . I’m just too jaded about everything now. . . . It would only embarrass me. I get embarrassed a lot!

A year earlier, on his blog, he had addressed his Joseph Smith work like so:

Growing up in a Mormon family, I understand that Joseph’s life has played a part in who I am at least indirectly. My home was eventually split in half over the believe [sic] in his church. . . . Being told two different things about the church from two different people who I loved equally, left me unsure of what to believe. Who was lying? Which one of my parents was going to go to hell? Ultimately I’ve learned to never fully trust or side with any two extremes. So now, in perhaps a misguided attempt to understand more about myself, I am researching and looking for the truth.

It’s been a long time since that (now-deleted) post was published in 2010, and the stuff Van Sciver produced those first few years may have been published here and there, but they didn’t make it into his final (massive) version of the Joseph Smith story. But there’s something fitting about that early First Vision beginning by quoting James 1:5 over a quarter-page and then subjecting a kid to the terrors of God. It’s a little dangerous to ask a God who gives liberally.

Incidentally, at the end of his new book, Van Sciver states that after “years immersed in an independent study on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints . . . travel[ing] to historic sites all over the country and read[ing] books, [going] to church, listen[ing] to hymns, and [writing] like the Devil was chasing me. . . . my study is finished. And I have the answers I was searching for, too.” I’m happy for him.

And I’m happy for us that his journey ended with this novel, which makes a strong claim as the greatest novel to date about Joseph Smith, graphic or not. To understand this, you need to know that in the past decade-plus, Van Sciver hasn’t just been researching Church history. He has also researched and published an excellent novel about Abraham Lincoln’s early-adulthood depression.[2] His work has been nominated for the Ignatz Award nine times and shortlisted for two Association for Mormon Letters Awards, winning one of each.[3] He has become a widely respected force in independent comics on the strength of his work, and Joseph Smith and the Mormons is his magnum opus.[4]

As a work of literature, as a work of comics, as a 456-page piece of art, Joseph Smith and the Mormons never stops being impressive. And it never shies away from the ambiguities of the prophet’s life. Great men make the greatest blunders, and Van Sciver finds much to explore in both the enormous highs (preaching to great crowds, falling in love with Emma) and the enormous lows (the Kirtland Safety Society, seducing younger women). But his goal is never hagiography or tabloid shockers—Van Sciver is trying to understand a complicated man.

One way to understand his result is to imagine the coherent single tale of Knaupp and Velluto and the fractured vision of Elwood combined into one actual human being—someone who lives one version of his life, yet that version is filled with both leaps and stumbles. Van Sciver’s Joseph Smith is a human being you can believe existed. He is not reduced to symbol or totem—he is a man.

And its breadth of represented moments and aspects makes for an incredible read. Four hundred fifty-six pages have never felt so short or so deep. Joseph Smith and the Mormons is the most deeply felt graphic novel of my experience since Jeff Lemire’s Essex County—or maybe I need to reach even further back for a suitable comparison. Expect to have your heart twisted in and out of shape, chapter by chapter. While Pillar of Light and The Glass Looker are both excellent, neither of them is reaching for literary accomplishment as a primary goal. Van Sciver reaches and grasps hold.

One last note on Joseph Smith and the Mormons: Van Sciver states in his author’s note that his “approach . . . was to tell the story . . . as straightforwardly as I could and to let readers draw their own conclusions. To this end, I decided not to portray any of the more extraordinary events as they were happening and instead chose to portray them as accounts being told to others. These miracles and visions are portrayed in blue line and without color.” This is not strictly true. The blue-line plan is a reasonable artistic decision and it does work well throughout the text, but there are exceptions—the angel’s appearance to Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and David Whitmer; the Kirtland Temple dedication; an angel at Joseph’s moment of death. I will leave it to the next round of criticism to explore the meaning of these exceptions, but for now I will only say that whatever journey Noah Van Sciver undertook to create this masterpiece, the resulting comic is potent evidence that it mattered—and will continue to matter to us as readers for a long time.

Andrew Knaupp and Sal Velluto. Pillar of Light: Joseph Smith’s First Vision. Latter-day Saint Ideas, 2020. 36 pp. Paper: $29.00. ISBN: 979-8624658783.

Mark Elwood. The Glass Looker: Collected Tales of Joseph Smith, vol 1. Luman Books, 2021. 150 pp. Paper: $35.00. ISBN: 978-1-7378392-0-0.

Noah Van Sciver. Joseph Smith and the Mormons: A Graphic Novel. New York: Abrams ComicArts, 2022. 456 pp. Hardcover: $29.99. ISBN: 978-1419749650.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Scare quotes 90 percent intentional.

[2] Noah Van Sciver, The Hypo: The Melancholic Young Lincoln (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2012).

[3] The Ignatz was for My Hot Date, a story from his adolescence, also nominated for an Association for Mormon Letters Award. His AML Award-winner was One Dirty Tree, another memoir, this one about the breakup of his family. One Dirty Tree explores the role religion played during those years for the Van Scivers, as discussed above.

[4] At least so far!

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue