Articles/Essays – Volume 50, No. 3

“Infected With Doubt”: An Empirical Overview of Belief and Non-Belief in Contemporary American Mormonism

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

Daniel, twenty-eight, is an active Church member and temple worker who served a mission and now holds a calling as a young single adult representative for his stake. He says he has both seen and performed miracles, and has a strong belief in Jesus Christ. But he has also struggled at times with doubt, which he says has “come along in many different forms” throughout his adult life. In part, his own questions were intensified by the fact that six of his eight siblings have left the Church—including his twin. “That was one of the most difficult times for me, when it seemed like one after the other, members of my family were leaving the Church,” he says. “I had to go through every part of the gospel one by one: What makes us different from other churches? Why should it matter that I’m Mormon? What does it mean to have the priesthood? What is Christ in my life?” It was a lonely and challenging period, but he got through it by remembering all of the times he had felt the Holy Spirit and witnessed the power of God at work in priesthood blessings. He is grateful to feel like he is on the other side of that faith crisis now, though he also says he is “amazed that it came out the way it did.”

Daniel is far from alone in having doubts. After many years on the periphery of mainstream discourse, the topic of religious doubt has recently emerged onto the public agenda in Mormon culture. Many have noted how the internet has radically changed the traditional terms of who controls access to information about Mormon history and doctrine, giving rank-and-file Mormons access to arguments, evidence, and perspectives that contradict many traditional Mormon narratives. The institutional Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has moved in fits and starts as it struggles to adapt to this new reality, sometimes embracing a new path forward (e.g., the Joseph Smith Papers Project, the release of several Gospel Topics essays dealing with difficult doctrinal and historical issues, new offerings from Deseret Book dealing with faith and doubt, and the restructuring of the youth Sunday School curriculum) and other times resisting and retrenching (e.g., high-profile excommunications of intel lectuals and activists, warnings by General Authorities to be wary of information on the internet and Mormon blogs, etc.).

This topic is important because the introduction of doubt into a Mormon’s religious worldview is often (although not always) associated with a change in one’s relationship with the Church and level of activ ity. Understanding the prevalence, causes, and consequences of doubt is thus a critical question. To date, there have been a handful of attempts to answer these questions using public opinion surveys of varying designs and degrees of methodological rigor.Survey data on Mormon behavior and attitudes in the United States are difficult to reliably measure because self-identified Mormons make up less than 2 percent of the US population,complicating the process of finding a large enough sample size through the standard approach of random-digit telephone dialing to ensure that the results are representative and statistically valid.

Here we seek to add to our understanding of faith and doubt in contemporary Mormonism by examining fresh results from a study of Mormon attitudes and behavior called The Next Mormons Survey (NMS).We designed this online survey, with input from multiple social scientists, to sample self-identified Mormons and former Mormons in the United States. The survey firm Qualtrics fielded the NMS from September 8 to November 1, 2016 using a panel-matching technique to achieve as representative a sample as possible.In all, 1,156 self identified Mormons were included in the final sample, as well as 540 former Mormons. A comparison of the demographic characteristics of the NMS sample with that of the 2014 Pew Religious Landscape Study (which was based on a representative telephone sample) showed that the NMS attained representativeness for currently-identifying Mormons on almost all demographic categories except for gender, education, and age. A statistical weighting procedure was used to correct for those sample biases.The survey results reported here can thus be considered representative of the United States Mormon population as a whole. To our knowledge, the 2016 NMS is the most comprehensive and extensive sample of contemporary Mormon attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors collected by independent or academic researchers to date. For our current purposes, we take a close look at responses among those who currently identify as LDS in the NMS to explore the prevalence and consequences of doubt in contemporary American Mormonism.

The survey data are also enhanced by inclusion of several excerpts from Jana Riess’s dozens of oral history interviews, mostly with members of the Millennial generation who are or used to be LDS. These ninety-minute interviews were conducted mostly by phone following a template that covered childhood, adolescence, missionary experiences (where applicable), temple experiences (where applicable), religious belief and behavior, and family life. All interviewees are identified here by first name only, either their given first name or one of their choosing to protect their anonymity.

How Many Doubters Are There?

The 2016 NMS asked respondents about their belief in the teachings of the LDS Church, prompting them to select one of five statements. Table 1 shows answers among all Mormon respondents: [Editor’s Note: For Table 1: NMS Responses Among Self-Identified Mormons on Belief in LDS Teachings, see PDF below, p. 5]

Here we see that the vast majority of self-identified Mormons in the United States report a strong level of belief in the teachings of the LDS Church. Nearly half say that they believe “wholeheartedly” in “all the teachings” and another third say that they believe many or most of the teachings. A little over one in ten say that some LDS teachings are “hard for me to believe” and roughly 5 percent say that they believe few or none of the teachings of the LDS Church. The question of “how many doubters” there are in the LDS Church depends to some extent on how one defines “doubter.” At a first pass of the survey results, about 17 percent of Mormons express at least a moderate degree of doubt in the teachings of the LDS Church.

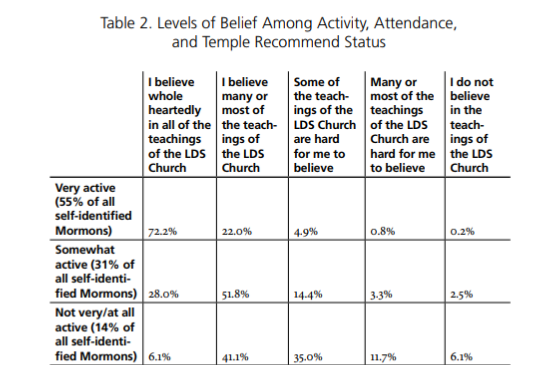

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2: Levels of Belief Among Activity, Attendance, and Temple Recommend Status, see PDF below, pp. 6–7]

Table 2 breaks this down further by self-described church activity level.As one might expect, doubting is more common as activity decreases, with about 6 percent, 20 percent, and 53 percent of active, less active, and inactive Mormons saying that at least some Church teachings are hard for them to believe. (Combining the first two categories, 11.1 percent of those who say that they are either “very” or “somewhat” active also express at least a moderate degree of doubt.) A similar pattern emerges when examining self-reported levels of church attendance. Among those who say they attend once a week or more, only about 9 percent express at least a moderate degree of doubt, compared to 22 percent of those who attend a few times a month and 54 percent of those who attend a few times a year or less.

We can also see that only about 4 percent of current temple recommend holders report at least a moderate degree of doubt compared to about 29 percent of those without a current temple recommend. So, while about one in six self-identified Mormons in the United States claims a degree of doubt, only about one in ten of active members who attend church weekly and about one in twenty of those with current temple recommends express doubt in some, most, or all of the Church’s teachings.

Personal and Social Characteristics of Doubters

We now turn to examine whether doubting is more or less common among various demographic and social subgroups of self-identified Mormons in the United States. To simplify the presentation and discussion of the results from this point on, we combine levels of belief and doubt into two categories: those who “believe wholeheartedly” and those who “believe many or most” Church teachings are grouped together as “Believers” and those who report that they believe some, few, or none of the teachings of the Church are grouped together as “Doubters.” We then show the frequency of Doubters among all self-identified Mormons in our sample, regardless of their activity level or temple recommend status. As can be seen previously in Table 2, though, self-described active members who attend church regularly are a strong majority of those in our sample.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 3: Prevalence of Doubting Among Demographic Subgroups, see PDF below, pp. 9–10]

Table 3 reports the percentage of all self-identified Mormons who also say that at least some Church teachings are hard for them to believe among a variety of demographic subgroups. For the most part, there is not a substantial degree of difference based on several demographic categories including age, gender, income, race/ethnicity, or convert status. Despite higher-than-expected numbers of Millennials and GenXers who are leaving the Church,those who remain and currently self-identify as Mormon are no more likely to be doubters than older Latter-day Saints. We do see that education makes a difference: those most likely to doubt are both those without a college degree (20 percent) and those with a post-graduate degree (14 percent) compared to those with a college degree (10 percent). Those who are divorced or separated are more than twice as likely to be Doubters than those who are married or widowed (28 percent vs. 12 percent, respectively). When it comes to partisanship, those who identify as political Independents are much more likely to also identify as Doubters than either Republicans or Democrats (31 percent vs. 13 percent and 20 percent, respectively).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 4: Prevalence of Doubting and Mormon Social Networks, see PDF below, p. 11]

Table 4 displays the frequency of doubting among people with varying levels of Mormons in their family and friendship circles. Here we see much more pronounced differences than was the case with demo graphic differences. In each case, the fewer Mormon family and friends someone has, the more likely he or she is to be a Doubter. This is most often the case for those who have zero close friends who are Mormon (44 percent) and zero extended family members who are Mormon (35 percent). Doubting also increases as the number of family members and friends who have left the Church increases—as we saw in the oral history interview with Daniel related in the introduction. We can also observe that doubting is least common among those whose closest friends are all Mormon (4 percent) and whose extended family are all Mormon (7 percent).

[Editor’s Note: For Table 5: Prevalence of Doubting and Youth Activity, see PDF Below, p. 12]

Table 5 focuses specifically on those who grew up Mormon or converted before age seventeen (or in other words, it excludes self-identified Mormons who are adult converts). It shows the frequency of doubting based on one’s level of activity growing up or level of involvement with various Mormon youth programs. We can observe here some interesting differences. For example, about 9 percent of returned missionaries are Doubters compared to 22 percent of those who did not serve a mission. Doubters are also less common among those who attended singles wards compared to those who did not (11 percent vs. 24 percent). Table 5 also shows that participating in seminary makes a larger difference: only 7 percent of those who attended seminary regularly growing up now identify as Doubters compared to 30 percent of those who did not attend seminary or attended only infrequently. Frequency of childhood church attendance also makes a difference. Only 13 percent of those who attended weekly in their youth now identify as Doubters, compared to 33 percent who attended only occasionally. It is also notable that there is no difference in frequency of Doubters depending on whether someone grew up inside (17 percent) or outside (16 percent) of Utah.

Of course, there is likely a large degree of overlap between these various categories. We saw, for instance, that there are fewer Doubters among those who attended seminary regularly growing up but also among those who have more family and friends who are Mormon. It is also the case that those with more Mormon family members are more likely to attend seminary. So, which of the two is associated with levels of doubt once we have taken into account the effect of the other? To examine this question, we can statistically estimate the effect of each of the individual factors on the likelihood of identifying as a Doubter while simultaneously controlling for the overlapping effect of all the other factors that could also make a difference.In other words, we can estimate the difference that one factor makes comparing two hypothetical people who are identical on all other factors included in the analysis. This reveals that after controlling for each of the factors examined above, some factors make a difference while others do not.

Education: those with less than a high school education are 16.8 percent more likely to identify as a Doubter compared to 4.2 percent of those with a post-graduate degree.

Frequency of church attendance: those who report that they never attend church services are 61.6 percent more likely to identify as a Doubter compared to 3.4 percent of those who attend more than once a week.

Marital status: those who are not currently married or who are divorced are 11 percent more likely to identify as a Doubter compared to 7.1 percent of those who are married, remarried, or widowed.

Childhood friends who have left the Church: those who say that all of their childhood friends have left the Church are 17.9 percent more likely to identify as a Doubter compared to 4.8 percent of those who say that all of their childhood friends are still members.

Close friends who are LDS: those who say that none of their five closest friends are LDS are 17 percent more likely to identify as a Doubter compared to 5 percent of those whose five closest friends are all LDS.

Family who are LDS: those who say that none of their extended family is LDS are 14.3 percent more likely to identify as a Doubter compared to 5 percent of those who say that all of their extended family are LDS.

In general, it seems that the two strongest factors of predicting doubt in contemporary Mormonism are church attendance and social networks. Those who attend regularly and have more Mormons in their social networks are more likely to be Believers, while those who attend less regularly and have more non-Mormons in their family and friendship circles are more likely to be Doubters. Those who are married and have advanced degrees are also more likely to be Believers than Doubters.

Aside from these factors, this analysis also revealed that age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, convert status, Utah vs. non-Utah residence, and political partisanship make no difference in predicting whether someone is a Believer or a Doubter. It is also notable that that the number of family members who have left the Church does not make an independent difference in predicting the likelihood of someone being a Doubter once controlling for the other factors described above. Friends leaving the

Church seems to matter more than family leaving the Church. As a final analysis, we can examine the effect of activity growing up and participation in youth programs among those who were raised in the Church or converted before age 17. This was done by repeating the analysis above but including variables measuring how often the individual attended church growing up, their participation in seminary, whether they went on a mission, if they grew up inside or outside of Utah, and if they attended a singles ward. In this analysis, the only additional factor that independently predicts the likelihood of identifying as a Doubter in one’s adulthood is attending seminary. Those that attended seminary all four years are nearly 10 percent less likely to identify as Doubters than those who did not attend (14.7 percent vs. 5.4 percent, respectively).In other words, this suggests that consistent seminary attendance in one’s youth can potentially triple the likelihood of identifying as a Believer in one’s adulthood.

While there is likely some dual-causation going on (seminary decreasing doubt in adulthood while those more likely to attend seminary are also more likely to be Believers regardless), the fact that this analysis controls for other factors that are also correlated with strong activity growing up (e.g., serving a mission) strongly suggests that attending seminary has at least some causative effect on the likelihood of being a Believer later in life. Many oral history interviews have anecdotally confirmed the “seminary effect” as well. Marie, 24, credits her seminary attendance in high school with the fact that she is still strong in the Church today. Gesturing to the other side of the room during an interview, she identifies a line on the carpet and uses it as a metaphor of a threshold. “My experience as a youth was to push me back really far this way, away from the line,” she explains. “But as I’ve grown intellectually and spiritually, I’ve gone closer to that threshold. And if I hadn’t been anchored in that way from seminary and Young Women, I would have passed right through that threshold.” While she recognizes that what is taught in seminary is a “controlled narrative” that does not include what she now understands as more complex truths about Church his tory and doctrine, the tasks of learning the scriptures intimately and having to prepare and lead devotions for her fellow students made an impact. “Those are important exercises that help you find a grounding. And there’s a lot of positive affirmation because it does fill your life with goodness, and it’s hard to forget that.”

But the “seminary effect” is hardly a magic bullet. For example, Zach, now 20, has recently become inactive in the Church after attending release time seminary in high school and serving a mission from which he had to return early due to an intestinal illness.While he enjoyed seminary and says he learned from it, he was also sometimes bored, sleeping through class if he felt particularly exhausted. For him, seminary might have been more helpful had it been a more complete education. After returning from his mission he became friends with a group of friends who exposed him to many things about Church history he didn’t know, including uncomfortable facts about Joseph Smith’s practice of polygamy. “I kind of knew that, but hadn’t really known that,” he says. “I was like, ‘What else don’t I know about the history of the Church that I never got taught in church?’” His research into polygamy led to other issues as well, including difficult realizations about the Book of Abraham, changes to the temple ceremony, and historical inconsistencies within the Book of Mormon. He prayed harder, continued reading the Book of Mormon, and went to the temple, where he asked Heavenly Father what he should do. Sitting in the celestial room, he received his answer. “I felt, as clearly as I had felt when I got a testimony of the Book of Mormon, that I was supposed to leave the Church.” He now considers himself a “hopeful agnostic.”

Zach’s experience illustrates one aspect of the importance of social networks in the spectrum of belief and doubt. While some criticized President Eyring for using the phrase “infected with doubt” in a 2013 general conference address, it ultimately seems that the metaphor was appropriate at least in one way: doubting is statistically more likely to be associated with the Mormon composition of one’s social networks than it is one’s demographic characteristics or how engaged someone was in Mormon programs and activities growing up (though, as stated above, seminary is a bit of an exception). Those who have friends and family who are Mormon and stay Mormon tend to be Believers, while those who have friends and family who are not Mormon or stop identifying as Mormon are more likely to be Doubters. We can infer, then, that doubting may indeed spread like an “infection.”

Believers vs. Doubters on Mormon Belief, Behavior, and Identity

We now turn to an in-depth comparison of Mormon Believers and Doubters on a variety of outcomes of interest, specifically their levels of religious belief and behavior as well as their levels of Mormon religious identity. We will present the findings in a series of tables that indicate the proportion of Believers and Doubters who would either agree with the statement or match a characteristic in a given row.

Religious Belief

The NMS presented respondents with a series of faith statements and asked them to indicate their level of confidence in each statement. Specific options were:

“I am confident and know this is true.”

“I believe and have faith that this is probably true.”

“I believe this might be true, but I have my doubts.”

“I believe this is probably NOT true.”

“I am confident and know this is NOT true.”

In Table 6 we combine the first two options together, so the table reports the percentage of both Believers and Doubters who would say that they are “confident and know this is true” or “have faith that this is probably true.” Also, the results in Table 6 should be read from left to right. For example, the first line in Table 6 shows us that 95.6 percent of Believers who are active in the Church are confident in their belief in God, compared to 67 percent of Doubters who are active.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 6: Confidence in Faith Statements Among Believers and Doubters, see PDF below, p. 19]

Earlier we defined Mormon “Doubters” as those who say that at least “some of the teachings of the LDS Church are hard for me to believe.” Which beliefs specifically, though, are hard for the Doubters to believe? For the most part, we can observe that there is widespread belief in most of the basic tenets of Mormon doctrine and theology among Believers, usually more than 85 percent. The only propositions where confidence drops below 80 percent occur when it comes to priesthood eligibility for certain groups: only about three-quarters of Believers are confident that the priesthood ban on blacks was inspired by God, or that the priesthood is reserved only for men.

On the other hand, Doubters are more confident of some Mormon faith propositions than they are about others. For example, roughly half to two-thirds of Doubters who are active in the Church are confident in the basic beliefs that Mormons share with other Christians, including the reality of God, the divinity of Jesus, a literal resurrection, and the expectation of an afterlife. On the other hand, only about a quarter to a third of Doubters are confident in the more unique beliefs of Mormonism, including the exclusivity of priesthood authority necessary to dispense salvific ordinances, the calling of Joseph Smith and contemporary General Authorities as prophets, the historicity of the Book of Mormon, and God’s corporeal nature. Also, less than one in five Doubters believe the LDS Church to be the “only true faith leading to exaltation” compared to more than four out of five Believers.

In sum, both Mormon Believers and Doubters share a common faith in God and Christianity (broadly speaking), but they part ways when it comes to more uniquely Mormon interpretations of Christian beliefs and the exclusive nature and authority of the LDS Church and its leaders.

This is also evident by examining the degree to which Believers and Doubters look to Church authority as a guide for moral and ethical decision-making. Survey respondents were presented with two statements about deference to Church leaders and asked which comes closer to their view: “Good Latter-day Saints should obey the counsel of priest hood leaders even if they don’t necessarily know or understand why,” or “Good Latter-day Saints should first seek their own personal revelation on a matter and act accordingly, even if it is in conflict with the counsel of priesthood leaders.” Among Believers, two-thirds (63.5 percent) said that good Latter-day Saints should obey priesthood leaders. This drops to only one-third (36.6 percent) among Doubters. Thus, two-thirds of Doubters say that personal revelation trumps ecclesiastical authority.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 7: Moral Authorities Among Believers and Doubters, see PDF below, p. 21]

We also asked respondents to rank their top five sources of authority that they “listen to when making moral decisions.” Options included LDS general and local authorities, personal conscience and promptings of the Spirit, friends and family, philosophy and reason, etc. Table 7 displays how many Believers and Doubters listed each moral authority as one of their top five most important sources when making moral decisions. We can see that the primary sources of moral authority for Believers are promptings from the Spirit, the scriptures, family members, and their own consciences, with general and local authorities not far behind. Looking at this another way, on a scale of zero to five (zero being not in the top five and five being the most important source of moral authority), Believers on average rank personal promptings from the Spirit the highest at 2.5, followed by personal conscience (2.2), family members (2.0), and the scriptures and LDS General Authorities (1.8).

Doubters, for their part, are more likely to look to their own conscience as well as family members and friends as their key sources of moral authority. They are somewhat more likely to look to philosophy/ reason, societal norms/values, and professional counselors and therapists than are Believers. About two in five Doubters trust in the scriptures or personal promptings of the Spirit and fewer than one-quarter list general or local Church authorities as one of their top five most important sources of moral authority. On the same scale of zero to five, Doubters on average rank their personal conscience as the most important source of moral authority at 3.5, followed by family members (2.4), friends and coworkers (1.6), promptings of the Spirit (1.4), the scriptures (1.2), and reason/philosophy (1.1). For Doubters, LDS General Authorities rank near the bottom at 0.4, lower than societal norms and values (0.7) and professional therapists and counselors (0.5). It is interesting to see that friends and coworkers rank as the third most important source of moral authority for Doubters, while for Believers they do not appear in the top five. This is significant considering what we have already seen about Doubters’ social networks, that they have fewer Mormon friends than do Believers. It seems that Doubters have more friends outside the Church and they hold in high regard the moral authority of their friends.

One final aspect of Mormon belief we can examine is how Believers and Doubters compare when it comes to troubling issues with Mormon doctrine, history, and practices. The 2016 NMS asked respondents: “Below is a list of things that some Mormons (or those who were Mormon at one point in their lives) feel are troubling to some extent. Please indicate whether each of these issues is very troubling, a little troubling, or not at all troubling to you.” Table 8 shows what percent of Believers and Doubters who say they are “very troubled” by each of these issues. (Note that this is not the same as the percent of former Mormons who were asked which of these issues were responsible for their decision to leave the Church.)

[Editor’s Note: For Table 8: Troubling Issues Among Believers and Doubters, see PDF below, p. 23]

The issues that seem to be most troubling for Doubters are Joseph Smith’s polygamy and polyandry, and specific policies and practices of the contemporary Church. About half of Doubters say that they are very troubled by Joseph sealing himself to multiple women (50 percent), including women who were already married (57 percent), compared to only a fifth to a quarter of active Believers who say that they are very troubled by this (20 percent and 25 percent, respectively). We also see that about half of Doubters are very troubled by the Church’s position on LGBT issues (49 percent), lack of financial transparency (49 percent), the priesthood/temple ban (50 percent), and recent excommunications of feminists, intellectuals, and activists (45 percent). It is especially important to note that Doubters are slightly more troubled by what the Church is doing right now than they are by most other historical or doctrinal issues, such as seer stones or multiple accounts of the First Vision. (For their part, somewhere between 15 percent to 25 percent of Believers say they are also very troubled by these issues, with the priesthood ban, Joseph Smith’s polyandry, and excommunication of feminists and intellectuals being the top three most troubling issues for active Believers.)

Religious Behavior

[Editor’s Note: For Table 9: Frequency of Religious Behaviors Among Believers and Doubters, see PDF below, p. 24]

When it comes to religious behavioral expectations that are promoted by LDS Church leaders as normatively desirable and things that, generally speaking, good Mormons are “supposed” to do, we can see in Table 9 that Doubters are universally less likely to adhere to these behavioral expectations than Believers. One of the largest differences between Believers and Doubters is whether or not they hold a current temple recommend. About 59 percent of Believers say they have a current recommend compared to only 13 percent of Doubters, a difference of about 46 percent. This suggests that a generally reliable predictor of whether someone harbors doubts about LDS Church teachings is whether their temple recommend is current. In fact, 41 percent of Doubters report that they used to have a recommend but no longer do. (This also suggests that a great many Doubters were likely at one time Believers.)

Otherwise, some of the clear differences in Table 9 between Believers and Doubters include making regular home or visiting teaching appointments (71 percent vs. 25 percent and 63 percent vs. 22 percent, respectively) and regularly paying a full tithe, whether calculated on net or gross income (76 percent vs. 28 percent). There is a clear difference when it comes to opinions about wearing garments. About a third of Doubters say that it is acceptable to remove your temple garments “if you don’t feel like wearing them” compared to only about 6 percent of Believers. Doubters are also about a third less likely to report that they pray and read their scriptures daily (although not even a majority of Believers report that they read scriptures daily) and are about 27 points more likely than Believers to say that they saw an R-rated movie sometime in the last six months. Believers are also about 20 points more likely to stay in their “church clothes” all day on Sunday, even when not at church, though this is not a majority activity even for Believers. In terms of church attendance specifically, roughly four-fifths of Believers attend church weekly compared to about two-fifths of Doubters. Also, attending church is a significantly better experience for Believers than for Doubters. More than half of Doubters (60 percent) say that they feel “tired or burned out” after church is over, compared to only about one in ten Believers.

In sum, this evidence suggests a broad generalization that Believers adhere to the behavioral expectations of an active Mormon lifestyle about two-thirds of the time, compared to Doubters who adhere to these behavioral expectations only about one-third of the time.

Mormon Identity

[Editor’s Note: For Table 10. Mormon Concepts of Identity Among Believers and Doubters, see PDF Below, p. 27]

For our final comparison of Believers and Doubters within contemporary American Mormonism, we can examine levels of personal identification with and affinities for Mormon identity, culture, and communities. First, we can compare in Table 10 how Believers and Doubters define what being a “good Mormon” looks like. A strong majority of both groups agree that believing in Jesus Christ as the Savior and working to help the poor and the needy are either essential or important to being a good Mormon. Only about three-fifths of Doubters, however, think it’s important to believe that Joseph Smith saw God and Jesus Christ in the First Vision or to obey the counsel of LDS General Authorities in order to be a good Mormon, compared to almost all Believing Mormons. Interestingly, both groups registered a drop in the percentage who see obeying the coffee and tea portions of the Word of Wisdom as important to Mormon identity, to about three-quarters of Believing Mormons and two-fifths of Doubting Mormons.

We can also see that a strong majority of Believers agree that being a Mormon is an essential part of their identity or that they talk about Mormons as “we” rather than “they.” In contrast, only about half of Mormon Doubters feel the same. There are also differences when it comes to interactions with their wards and branches. About a third of Believers try to interact with ward members throughout the week compared to only about 14 percent of Doubters. Neither group sees the ward as their primary social network; only about a quarter of Believers rely on their ward for socializing compared to about one in ten Doubters.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 11: Favorite Part of Being a Mormon for Believers and Doubters, see PDF below, p. 29]

Survey respondents were also asked what their “favorite part about being a Mormon” was. They were presented with a variety of options and asked to indicate up to three. Table 11 shows that there is a good deal of diversity in terms of people’s favorite aspect of their participation in the Mormon community. Believers, however, tend to focus more on the belief-oriented aspects of its emphasis on Jesus Christ, eternal families, and providing peace in hard times. For example, a little over half of Believers list the Church’s focus on Jesus Christ as one of their top three favorite parts about being a Mormon. Doubters, on the other hand, are more likely to express appreciation for the strong community at church as well as the peace they find in hard times. For example, Doubters are about 14 percent more likely to list a “strong community” and 12 percent more likely to list the “focus on children and youth” in their top three favorite things about being a Mormon than are Believers. It is interesting that more Doubters than Believers appear to value “the good health and freedom that comes with keeping the Word of Wisdom” as a favorite aspect of LDS identity.

One final way we can measure integration and commitment to the Mormon community is by respondents’ intended long-term relationship with the LDS Church. We asked members to indicate on a scale of zero to ten, “how confident are you that you will remain a committed Mormon throughout your life?” As we might expect, members who report being either very or somewhat active are more committed to life-long membership, with an average commitment of 8.9 on the zero to ten scale, with a majority (54 percent) indicating a full “10” and more than nine out of ten indicating a score of “6” or above. When we break this down among Doubters, however, we see that the average level of commitment to life-long membership is only a 5.7. Among Doubters specifically, about a quarter gave a score of a “5,” another quarter indicated a score of “0” through “4,” and about half indicated a score of “6” or higher. Only 11 percent of Doubters gave a score of “10.” It is safe to say that long-term commitment to membership is significantly lower among Doubters than among Believers. That being said, it is encouraging that a substantial portion of Doubters still indicate, on balance, an intention to remain committed members for the rest of their lives.

Summary

To briefly summarize, a novel source of data on Mormon beliefs and behaviors shows that approximately 17 percent of self-identified Mormons in the United States express at least a moderate degree of doubt in the teachings of the LDS Church. That figure drops to 11 percent among those who say that they are at least somewhat active in their membership and 10 percent among those who attend church at least a few times a month.Mormon Doubters are hard to pin down by their demographic characteristics. Contrary to conventional wisdom, there is not a strong difference between Doubters and Believers when it comes to age, gender, income, or even political partisanship. Instead, Doubters are most common among those who attend church less often and those whose family and friendship circles are mostly non-Mormon or former-Mormon. There is also some evidence that one’s level of activity growing up makes a difference: those who did not participate in or complete all four years of seminary are also more likely to be Doubters in adulthood, even after accounting for other likely variables.

In terms of personal belief, Doubters express the most doubt in many of the unique truth claims of the LDS Church and its exclusive claim to authority. While they are also less likely to express belief in God or the central tenets of Christianity than Believers, a solid majority of Doubters still express confidence in the reality of God and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. When it comes to moral authority, Doubters are more likely to place confidence in their own consciences and the opinions of their friends and family, while Believers place the most confidence in personal promptings from the Spirit and the counsel of General Authorities. Doubters also report that they are most troubled by Joseph Smith’s polygamy and polyandry, as well as the Church’s contemporary stands on social issues such as same-sex marriage and race as well as its high-profile excommunications of feminists, intellectuals, and activists.

In almost every measurable way, Mormon Doubters have lower levels of religious behaviors that the LDS Church considers to be normatively desirable: they are less likely than Believers to attend church weekly, engage in prayer, fulfill their callings, pay tithing, and perform home or visiting teaching. They are also less strong in their Mormon identities, as about half of Doubters talk about Mormons in terms of “they” rather than “we.” They say that their favorite part of being a Mormon is the strong sense of community at church and the peace their faith provides them in difficult times. And while they are less sure about their long-term affiliation with the LDS Church than are Believers, a little over half of Doubters still express confidence that they will remain active members through the rest of their lives.

Discussion and Conclusion

These findings confirm some common stereotypes about Mormon Doubters but challenge some others. Specifically, anecdotal evidence has suggested that it is often younger Mormons or those with liberal political sensibilities that are more likely to express doubt than older members or political conservatives. Here, our findings are that Doubters are about as common among self-identified older Mormons as well as younger ones, and among conservative Mormons as well as liberal. What can we make of this? On the one hand, it could be the case that the anecdotal evidence is simply incorrect in the aggregate. It is possible that younger Mormons are just as strong in their testimonies of orthodox Mormon belief as older members.

On the other hand, our findings may also be attributable to the nature of the sample in the survey. Similar to surveys conducted by other organizations (Pew, Gallup, etc.), we rely on respondents to identify for themselves whether or not they are Mormons. This is different than how the LDS Church defines membership, as the Church includes those who were born members or who were baptized at any point, regardless of their present level of activity or association with the Mormon community. Many of those people the Church still identifies as members but who are inactive and have not attended Mormon church meetings for years may very well no longer identify as Mormons. This is also the case for those who no longer consider themselves members of the Church, but have not had their names formally removed from the membership rolls. It is likely that many Doubters eventually leave the Church and no longer identify as Mormons, in which case they would not be included in the sample of those that this survey defines as current Mormons.In this case, it is indeed entirely possible that younger people or political liberals are more likely to have left the Church because of doubts, meaning that they would no longer be included in the sample we analyze in this article; for example, there is evidence from the General Social Survey that Mormons born after 1971 have a ten- to fifteen-point drop in retention compared to older LDS generations.In this scenario, we would then say that among the Doubters who currently identify as Mormon, they are just as likely to be younger as older, or politically liberal as conservative, but that younger and/or liberal Mormons may be more likely to stop identifying as Mormon when they have doubts.

We can briefly assess this possibility by comparing the Mormons in our survey with the 542 individuals in the same survey who self-identified as former Mormon.These are individuals who reported that they identified as Mormon for at least one year before age eighteen but no longer identify as LDS. When comparing current Mormons and former Mormons, we find that 32 percent of current Mormons identify as either Democrat or Independent-lean-Democrat compared to 46 percent of former Mormons. We also find that 57 percent of current Mormons identify as Republican or Independent-lean-Republican compared to 38 percent of former Mormons. This provides further evidence that political liberals are more likely than political conservatives to disaffiliate from their Mormon identities at some point in their lives, leaving the political liberals who continue to identify as Mormon about as likely to be Doubters as conservatives.

We can also briefly take a closer look at what age former Mormons tend to disaffiliate from their Mormon identities. Former Mormons were asked: “About how old were you when you stopped identifying as a member of the LDS Church?” Among all former Mormon respondents, the average age is 21. This does not vary much by age cohort, though there appears to be a trend for disaffiliation at younger ages: the average age of de-identification for former Mormons who are currently Millennials is 18.4, Generation X is 21.1, and those of the Boomer or Silent generation is 23.7. Clearly young adulthood is the age when most former Mormons leave the fold, regardless of what age they are now.

Given this additional information, our tentative conclusion is this: younger people and those with liberal political leanings are more likely than older individuals and conservatives to disaffiliate with their Mormon identities. Among younger individuals and political liberals that continue to identify as Mormon, they experience doubts at roughly similar rates to older people and political conservatives. In sum, younger people are more likely to leave when they become Doubters, whereas older people are more likely to stay. Also, liberals are more likely to leave when they become Doubters, whereas conservatives are more likely to stay.

It would also be worth considering these findings from a broader perspective. While we find that Doubters make up about one in five Mormons and one in ten active Mormons in the United States, other research has shown that doubting is much more common in other American religious traditions, especially Catholicism and Mainline Protestantism.One could argue that Mormonism thus does a better job of encouraging belief and discouraging doubt among its members than other major American religious traditions. One could also argue, however, that there is more room within other faith traditions to have a wider diversity of belief among rank-and-file members. For example, a majority of US Catholics who are active in their faith believe that their church should allow its members to use birth control, permit priests to get married, and ordain women as priests, all in opposition to official Catholic teachings.It seems that many US Catholics do not feel the same pressure as Mormons to disaffiliate with their religious identity when they doubt specific teachings of their church.

This suggests to us that more Doubters might continue to identify as Mormons if there were more room for them to do so in a way that was culturally acceptable within their religious community. We asked the former Mormons in our sample to indicate which factors were most influential in their decision to leave the Church, both doctrinal and social. A full 38 percent of former Mormons indicated that one of the top three most important social or personal reasons for distancing themselves from the LDS Church was “I could no longer reconcile my personal values and priorities with those of the Church” with another 37 percent saying “I stopped believing there was one true church.” Another 30 percent said “I felt judged or misunderstood” as one of the top three reasons that they left. This would suggest that LDS leaders who wish to minimize attrition from the Mormon community might consider ways to “broaden the tent” so that individual members feel less pressure to have to choose between their beliefs and their place in the community.

In conclusion, we are pleased to be able to report what we believe to be the most comprehensive and in-depth independent analysis of faith and doubt in contemporary American Mormonism collected to date. If national trends continue, it is not unreasonable to expect that doubting will only increase in the coming years and decades. Various national studies of the US population have confirmed a rising trend toward disaffiliation in American religion, with the youngest generation showing the most dramatic change. For example, when Pew conducted its 2007 Religious Landscape Survey, 16 percent of American adults had no religious affiliation; in its 2014 Religious Landscape Study, that had jumped to 23 percent among all adults, and more than a third of Millennials.The overall growth in disaffiliation was caused not just by Millennials aging into the survey but by older Americans who had previously reported having an affiliation but decided to leave their religions between 2007 and 2014. Moreover, religious belief (which is not necessarily the same as institutional affiliation) also shows signs of softening in the general population, with declining percentages of Americans who say they believe in God without any doubts, pray daily, or attend church weekly.Much (but not all) of our research in The Next Mormons Survey confirms that national trend, with Mormons overall still having exceptionally high rates of belief and practice but Millennial Mormons lagging behind the rigidity of their elders. These generational differences will be explored in depth elsewhere, but for our purposes here we will simply conclude by saying that Mormonism is one of many religious traditions in the Western world faced with the trade-off between enforcing orthodoxy or “broadening the tent.” Time will tell which course the LDS Church ultimately decides on.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue