Articles/Essays – Volume 43, No. 4

In Lieu of History: Mormon Monuments and the Shaping of Memory

Editor’s Note: This article has footnotes. To review them, please see the PDF below.

The farther I go the more certain I am that the path towards my object does not exist. I have to invent the road with each step, and this means that I can never be sure of where I am. A feeling of moving around in circles, of perpetual back-tracking, of going off in many directions at once. And even if I do manage to make some progress, I am not at all convinced that it will take me to where I think I am going. Just because you wander in the desert, it does not mean there is a promised land.

—Paul Auster, The Invention of Solitude

As a missionary in France and Belgium, I frequently encountered devout Catholics who would describe their journeys to Lourdes or Fatima. “Ah, oui! J’ai vu la grotte, la grotte où la Vierge s’est apparue à Bernadette! J’étais lá!” While these humble women, dressed in robin-egg-blue housecoats, could not bring home a piece of the cross, they could show me their holy water, rosary beads, or skinned knees, emblems of their devotion and commitment. Their pilgrimage was no trite tourist trip. They didn’t watch the spectacle with ironic detachment, rolling their eyes at the commodification of sacred space. Non! They walked on holy ground. I nodded and smiled. But I confess that the stories amused me. Holy water indeed.

Those fanciful narratives were a counterpoint to the dull sermons I heard preached in off-white cinder-block chapels as a child. Speakers would often disparage such pilgrimages, emphasizing the holiness that is available to all of us here and now. What these sermons expressed, with an almost uncanny echo of nineteenth-century nationalism, was the core American myth. Emer son himself would have nodded in agreement, for the advice I heard as I sat on my oak pew merely echoed the Transcendentalist’s observation that “the soul is no traveller; the wise man stays at home.”We need not travel to Jerusalem and walk the paths of Je sus, gawking into empty tombs, imagining the voice of angels proclaim, “He is risen!” And we shouldn’t feel compelled to place our Nikes in the footsteps of our pioneer ancestors whose wagon wheels carved ruts through limestone in Wyoming. I eventually realized that these sermons were earnest attempts to create identity by emphasizing difference. Like seventeenth-century Puritans, Mormons like to separate themselves from Catholics and their “Popish rituals.”

Ironically, this particular difference has dwindled in recent years as the LDS Church pours money into historical sites that serve as Mormon pilgrimage destinations. The development of these places encourages families to visit, take guided tours, serve missions, and read about these sites in the Ensign, the New Era, and the Friend. Perhaps those Catholics were on to something.

I recently took my own pilgrimage to New England, visiting not only nationalist monuments like the Freedom Trail, Lexington and Concord, and Plimoth Plantation, but also Sharon, Palmyra, and Fayette, the Ur-locations of Mormonism. Of course, I’m not the first to make this pilgrimage, even with academic lenses. LDS geographer Michael H. Madsen provides a useful his tory of these sites, noting that in 1880 the Church largely ignored the eastern sites and didn’t attempt to commemorate them during Mormonism’s fiftieth anniversary. But twenty years later, Joseph F. Smith began to reacquire key historical sites, ultimately deciding that they could be “potential proselytizing hubs.”Following the model of heritage tourism sites like Williamsburg, leaders like David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee, and Spencer W. Kimball became more aggressive in acquiring the sites. Madsen reminds us that these sites initially had historical value, not an inherent spiritual value. In fact, some leaders, Bruce R. McConkie in particular, resisted the idea of sacred places or shrines, insisting that the Sacred Grove, for example, “is not a shrine in the sense that many denominations have shrines, nor is there any sanctity now attached to the trees and the land there located. But it is a spot held sacred in the hearts of those who believe in the truth of salvation, because they glory in the transcendent event that took place there.”As Madsen summarizes, “Only the event that transpired there is sacred.”

This attitude changed, and “by the end of the twentieth century, . . . this historical emphasis began to give way to a more spiritual interpretation of Mormon historical sites.”President Gordon B. Hinckley led the movement, investing enormous sums in acquiring and restoring land, homes, barns, stores, and other buildings. Also, “the post-1995 emphasis has definitely focused on members of the Church, deepening and strengthening their commitment to the Church through their personal spiritual experiences,”a change due to the fact that more members visit the sites than nonmembers.

During his site-visits, Madsen observed that the “rhetoric currently employed by the missionary guides at Mormon historical sites is a contributing factor in the sanctification of these places and . . . the missionaries often quote President Hinckley to authenticate the site’s holiness.”Madsen quotes one missionary who confirmed: “They’ve changed the focus of these sites from what happened here to what it means to us.”Madsen further notes that many claim that the building of LDS temples near these historical sites contributes to the sanctification of the landscape.

These Church sites are very different from, say, sites like Pearl Harbor, Gettysburg, or Concord in that civil monuments are not only sites of veneration, but, as battlefield historian Edward Tabor Linenthal reminds us, sites of defilement and redefinition. They are “civil spaces where Americans of various ideological persuasions come, not always reverently, to compete for the ownership of powerful national stories.”Linenthal insists that, “at a time in which Americans—often grudgingly and all too haltingly—recognize the strengths of cultural pluralism, no one can be allowed to win the struggle for exclusive ownership of these places. Indeed, no one should.” He asserts that Americans demonstrate their “ideological maturity” once they recognize that “there is more than one story to be told, and that these stories convey diverse, often conflicting interpretations of cherished patriotic orthodoxies.”As a result, the National Park Service, among other organizations, often invites multiple interpretations, and Linenthal hopes that this clash of voices will be creative and more inclusive. For example, Native American voices respond to those who honor Custer, guardians of the Alamo contest with Tejano ancestors, and Pearl Harbor is both a cautionary tale and an opportunity for reconciliation. The combination testifies to the complexity of the sacred places.

In contrast, the orthodoxy of one official story is what the LDS Church seeks. Perhaps it’s a sign of immaturity and a rejection of pluralism, but the LDS historical and missionary departments use their sites to unify, define, and limit. One of the most important insights in Madsen’s work is his observation that the Church is “using the physical places in which Mormon history occurred to nurture the ‘geographic memory’ of Latter-day Saints, hoping to promote a common sense of identity among an increasingly diverse membership. Place does matter in establishing and maintaining a Mormon identity tied to a prophetic and sacrificial past, perhaps even more so for those Church members who have no familial link to that past.”An identity rooted in geography makes sense, for this nexus of texts, geography, and spirituality—all packaged within a Restoration framework—should resonate with Mormons, given the connection among spiritual visions, books in mountainsides, and nearby woods. There is no Mormonism without reference to the Sacred Grove, the Hill Cumorah, or the Susquehanna River.

What interests me is how the LDS Church seeks to harmonize the potential conflicts, limiting the number of narratives available to visitors. This article explores the ways the Church prevents visitors from gathering the information they collect at the sites into stories that are at odds with officially sanctioned stories. It also probes the paradoxes and contradictions, the dilemmas and problems, embedded in the Church’s constructions of its spiritual landscape. While I don’t deny that the Church “promotes Mormon historical sites as sacred places,”I’m also interested in the ways these sites construct Mormon identity by denying the very historicity of these sacred places: Place, it turns out, doesn’t really matter in the way we think it does.

Geography as Memory

As my eighteen-year-old daughter and I visited the Grandin Press in Palmyra, Joseph’s boyhood home in Manchester, and the Peter Whitmer home in Fayette, what struck us is the fact that so little remains of the original structures. In a nod toward authenticity, workers used period tools to work bits of old and new materials to reconstruct from scratch the Joseph Smith log home. Eighty-five percent of the frame house his brother Alvin began is a reconstruction. The Peter Whitmer home was rebuilt from scratch. The Grandin Press shell is largely intact, but the Church acquired property next door and built around the back to make room for a visitors center. Nearly all the items within the press are facsimiles. The displayed copies of Charlotte Temple, Pilgrim’s Progress, and Aesop’s Fables, for example, are full of blank paper. The same is largely true at other sites I’ve visited recently: The Liberty Jail, aside from a few stones found at the lowest level, is a replica. Nothing remains at the Joseph Smith birthplace at Sharon, Vermont, beyond holes and the semblance of foundation stones. In short, the buildings—these structures where key spiritual events took place—are approximations and reconstructions. But there is nothing sinister about this, and the missionaries and guides do not hide the fact that we are looking at restorations and reconstructions. There is no deception here.

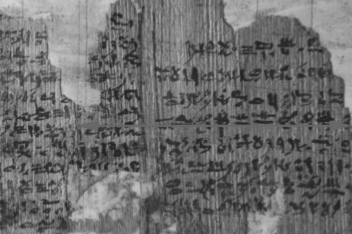

I ponder the significance of these pseudo-artifacts. While these simulacra may disappoint some visitors eager to walk where Joseph walked, I expect nothing more. As Plato insisted and as postmodern theorists, New Historicists, and anti-foundationalists of many stripes have reminded us, we do not have unmediated access to the past. Literary theorist Linda Hutcheon, among others, points out that we need not deny the existence of the past, but we should question whether we can ever know that past other than through its textualized remains. “Past events existed empirically,” Hutcheon insists, “but in epistemological terms we can only know them today through texts.”We not only learn of the past through incomplete representations (language and images being the most common, of course); but the narratives and reconstructions, no matter how helpful and informative, shape the meaning and significance of those events as well. Images of Joseph translating the Book of Mormon, finger running across the characters in scribed on the golden plate, plumed quill pen in hand, makes an extraordinary event almost homey and familiar, while an image of Joseph, face down in a hat peering at seer stones, unsettles us, casting the act of “translation” as bizarre and unseemly, even embarrassing. And there is no direct route. We cannot escape the “textual traces” and “mediators” that come between us and the empirical events and figures. Artists and historians become our docents.

And the missionaries certainly inserted themselves between us and the events. While we were keenly aware—told even—that we were staring at reconstructions, what I find interesting is the apparent disregard for this fact. As my daughter and I visited the second floor of Joseph’s cabin, Sister North, a young sister in a white shirt and light-blue skirt (all names are pseudonyms) proclaimed, “It was right here that the Angel Moroni appeared to Joseph Smith four times in one night.” As we visited the Smith home in Palmyra, Sister South pointed to a facsimile of a toolbox and explained that Joseph hid the plates in it. She pointed to the reconstructed fireplace and explained that Joseph buried the plates beneath the hearthstones when a mob approached. Referring to the reconstructed shed, she explained that the plates had been hidden there, too.

As I stood in Smith home on that friendly summer afternoon, watching the missionaries use these physical objects like cue cards, I recognized a relationship between memory and a particular place. That our experience of the past is mediated is especially relevant when we discuss personal and cultural memory, for memory is the result of this filtering and shaping process, a connection that has its roots in classical oratory. Loci mnemonics uses the structure of a place—real or imaginary—to recall people, places, events, and speeches. In fact, the connection between our idea of “topics” and its Greek root “topoi” (or place) should be familiar to anyone who has ever taken freshman composition. Following the Roman tradition, loci is Latin for “place,” as in our “lo cation,” and the mnemonic is based on a famous story in which the Greek poet Simonides was at a large dinner party.

Called outside to talk with two men, Simonides watched as the roof of the house caved in, killing everyone. No one could identify the bodies except Simonides who could recall his fellow guests by remembering where they were sitting. Using this story as a model, Greek and Roman rhetoricians memorized a great deal of information by associating what they wanted to say with rooms in a house or specific spots along a path. Orators already knew the design of their homes, so when they spoke to an audience, they just needed to imagine that they were walking through their own homes, remembering what section of their speech went with each part of their house. The idea is that we “walk through our house” and “pick up” information as we go. It is this process of associating what we want to remember with a specific place that is important to any discussion of place and memory, for the process reminds us that memory is tied to specific locations—that memory itself can be conceived spatially. So the sister missionaries were merely modern versions of Simonides, responding to the prompts as they rehearsed their script. And who says that classical mnemonics have lost their place?

But the strategy has its ripple effect: While the location may prompt the memory, the location also itself helps construct and organize the memory. Landscapes—the physical landscapes we use to invoke memory or the conceptual landscapes we use to remember events—shape the memories themselves. Place is yet another shaping force, yet another mediator of experience. While the past is irredeemably remote, it is also always undeniably contemporary, for our experience of the past occurs simultaneously with our perception of the past at the moment we locate it. Not only is the past mediated in the particular way it is presented to us, but the frameworks we bring to the experience shape the very way that we make sense of these mediations. This is a knot that needs unraveling.

The reconstruction of a place amounts to a creation of memory which entails a reshaping of the past. Imagine a diorama depicting a father pulling a handcart while a son pushes from behind. A mother and daughter walk side by side. This simple recreation invokes a cultural memory but also simultaneously shapes our perception of the experience. The event is a family affair. We must keep in mind, however, that reality could be otherwise. Families were often broken, and a spirit of unity did not always prevail. Thus, readers learn rather quickly that a new framework—we could call it a “lens”—changes the significance of the same event.

I’m not claiming that our descriptions alter the world itself; rather, our descriptions change its meaning and value. The past is not rewritten in the sense that we are more aware of what happened, a progressive notion of history informed by the Enlightenment. Instead, contemporary reconstructions provide new ways of seeing that, in the parlance of the academy, recode and resignify these representations retroactively. Put more conventionally by Marcel Proust, “The only true voyage of discovery, the only really rejuvenating experience, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees, that each of them is.” And Mormons need not go to early twentieth-century France when they have LDS artist James Christensen inscribing as part of several paintings the Latin phrase Credendo Vides or “By believing, one sees,”a claim that reverses our traditional notions of perception and evidence. We don’t see, then believe. We believe, then we see a different world, or we see the same world saturated with different meanings and significance.

What Sister North and Sister South provide during their tour is not new information, a new set of ideas, or even “revealed truth.” Rather, these missionaries are trying to fit us with a new set of glasses. To the unconverted with blurry vision, the restored homestead with its Indian corn hanging from the mantle, the tin plates and cups lying on the oak table, and the quilt with its log cabin design spread over the fluffed-up, straw-stuffed mattress are merely facsimiles of items owned by a poor nineteenth-century family whose son has a talent for spinning tales. The items reflect a sanitized basic farm life, perhaps enviable in its Disneyesque simplicity. Viewed through another lens, these household items—the very same items—offer a glimpse into the humble circumstances of a boy-prophet’s origins and testify of God’s willingness to work with the weakest among us. Proselytizing amounts to a lens-fitting, not a new message. Just as Jonathan Edwards finds God in a common thunderstorm,Mormons find a prophet beneath a shake roof. The evidence is always available to those who can see with new eyes.

Madsen argues that the acts of reclaiming and recoding these sites “nurture the ‘geographic memory’ of Latter-day Saints.” Yes, the LDS Church reframes and reconstructs the geography in an effort to reshape Mormon identity. And Madsen maintains that “new generations of Mormons cannot avoid understanding that the Church’s history unfolded at places made sacred by that history and that they themselves, by virtue of their membership in the Church, both own and belong to those sites.”While I can’t disagree with the claim that members’ identity is tied to these sites, it’s the particular process of reclaiming these sites that interests me.

My claim is that the Church, in a paradoxical move, avoids the messy historical contexts that ground events in specific times, places, and complicated cause and effect relationships. The Church decontextualizes and recontextualizes these sites so that they can speak to the present and the future. As physical sites, Palmyra, Harmony, Kirtland, Nauvoo, Winter Quarters, and Martin’s Cove still do not matter. Perhaps I’m putting too fine a point on this, but I would insist that the physical places are mere launching pads to offer a narrative that then constructs LDS identity. We still have not strayed too far from McConkie’s emphatic declaration that events, or the narrative describing the events, matter more than the places themselves.

Packaging the Past

My daughter and I return to Main Street, Palmyra, eat a few slices at Mark’s Pizza, and find our way again to the Grandin Press. I’m taken by the ruddy red brick with the window-trim in bright white decorating the front. A large sign, with gold and white lettering, announces “Book of Mormon: Historical Publication Site.” We pass through the front door and find ourselves in a lobby to be greeted by beaming sister missionaries in tan and taupe dresses. They ask if we are interested in a visit—“Of course”—and they ask us to watch a short video that describes Joseph Smith’s working relationship with Egbert B. Grandin.

Sister West, the older of the two, then initiates the tour. She presents a painting of Grandin and his wife, and then points out that Grandin was born one year after Joseph was born and died the year after Joseph died. She explains that, for her, this is not a coincidence. This proximity of dates suggests a kind of cosmic/spiritual connection. “Some say it’s coincidence, but I think they were meant to meet each other. It was part of a divine plan.”

This recoding of events reminds me of novelist and theorist Walker Percy’s “The Loss of a Creature,” where Percy explores the effects of this kind of mediation as he discusses travel, nature, and classrooms. He comments on the way, say, material gathered at a travel bureau provides a “symbolic package” that mediates our experience of the Grand Canyon. Percy claims that this “general surrender of the horizon to those experts within whose competence a particular segment of the horizon is thought to lie” amounts to a loss of sovereignty, a loss of openness, thus rendering us a “consumer of a prepared experience.”Sadly, the pleasure of encountering a raw experience is replaced by an experience that satisfies “by the degree to which the canyon conforms to the preformed complex.”We arrive at some version of, “Oh, I see what they mean. I see what they are talking about.” Percy acknowledges that an unmediated encounter with raw experience is problematic, but it’s a question of submission and subordination, a question of what role the paratext or “symbolic package” asks us to play.

Admittedly, we are not free of all forms of mediation. I suppose I’m less optimistic than Percy about the possibility of becoming completely sovereign. At the same time, however, Percy’s observation that “symbolic packages” make us consumers of prepared experience contains a great deal of sense, especially in the context of Church historical sites. The presence of explanatory plaques that often accompany the site and the missionaries who narrate the events provide a framework that limits possible connections, even as the narration clarifies and enriches our experience. This process may be comforting, a kind of buoy that keeps us afloat as we ride the waves of Church history, but it limits the proliferation of significance, undecidability, and indeterminacy. In short, these symbolic packages circumscribe meaning. The narratives take away even as they provide meaning. The missionaries, for example, do not remind us of Joseph’s claim that he found two stones in 1822 while digging a well that allowed him to see buried treasure and lost items, used magic circles, and penned multiple versions of the First Vision. The missionaries may not knowingly create gaps in the historical record, but the result is a simplified and sanitized portrayal of Joseph that shapes our perception.

Sister West’s packaging demonstrates a kind of creative reading that generates connections based on chronological proximity. Assuming that people are pieces that God plays with on a game board has its appeal, I suppose. She is able to endow seemingly random events—birth and death dates—with meaning. Had Jona than Edwards been standing with me on that hunter green carpet, he would have applauded her reading skills. I confess, however, that her conclusions were underwhelming. For the person who does not believe that God, like a divine puppeteer, controls every aspect of our existence, her correspondence theory seems less than compelling. She also eliminates other explanations: disease, accident, age, mere chance. She asks us to make sense of these dates within a spiritual framework, her symbolic package. Significance saturates the coincidental.

We encounter a more elaborate symbolic package near the Smith cabin. Next to a fence is a small placard that provides three kinds of information. One segment states that “On 22 September 1823, Joseph Smith Jr. was harvesting wheat with his father and brothers when he was overcome by exhaustion from the visits of the angel Moroni the previous night in the log home. His father sent him home to rest. His mother explained that the angel Moroni appeared to Joseph again as he rested under an apple tree.” The prose’s neutral tone—so matter-of-fact, conveyed in third person—roots the event in a historical context. Another segment recounts the events from Joseph’s point of view: “I started with the intention of going to the house, but, in attempting to cross the fence out of the field where we were, my strength entirely failed me, and I fell helpless on the ground. . . . I looked up, and beheld the same messenger standing over my head. . . . He then again related unto me all that he had related to me the previous night, and commanded me to go to my father and tell him of the vision and commandments which I had received.” This edited passage frames the experience from Joseph’s point of view, yet there is little sense of the experience being a vision per se. Although Joseph is exhausted, the description doesn’t encourage us to think that he is dreaming. The third element is a drawing of Joseph crossing the fence. This image of the wooded fence frames what we see in the present.

Each element—the reconstructed fence, the image of Joseph climbing the fence, the explanatory notes—reinforces the other. The physicality of the fence verifies the narration while the narration grants the fence spiritual significance. What is, at one level, a graying cedar fence is reframed as a form of evidence of a spiritual manifestation. We become, as Percy claims, consumers of a prepared experience. Everywhere I turned that weekend—the Smith homestead, the Hill Cumorah, the Grandin Press, the Peter Whitmer home—I surrendered a degree of my sovereignty; but the experience was still satisfying because what I saw and read echoed my expectations, expectations that the site, in fact, created in the first place through its use of symbolic packages.

I had occasion to ruminate on this experience during the remainder of the summer when I stumbled upon French historian Pierre Nora’s notion of lieux de mémoire (sites of memory), a concept that allows us to understand this play of presence and absence. Nora suggests that monuments and memorials function only as lieux de mémoire, for sites of memory are “entities” that, thanks to human will or time, become a symbol of a community’s heritage. Nora contrasts a “site of memory” with “real memory,” which is characterized by “the gigantic and breathtaking storehouse of a material stock of what it would be impossible for us to remember, an unlimited repertoire of what might need to be recalled.”In short, “real memory” is the totality of what actually happened while “lieux de mémoire” are what we encounter. But it’s still not that simple. Punning on the phrase au lieu de, which suggests both “to the location” but also “instead of,” Nora insists that lieux de mémoire occur “at the same time that an immense and intimate fund of memory disappears, surviving only as a reconstituted object beneath the gaze of critical history.”The image replaces the reality, for we embrace the representation in lieu of what really happened. Visitors do not root themselves in the past; rather, they root themselves in a substitution, a replacement, a surrogate. Thus, acts of memory are really acts of forgetting.

But are we all dupes? Are we all so weak-willed that the Church architects can fit us with lenses without our knowing? Admittedly, there are moments when this process is interrupted, when we can see fingerprints on the glass. While my daughter and I were touring the Vermont site, Sister East told a detailed story of how Church leaders bought the property and how they worked to bring the monument—that large obelisk—to the site. At one point, she explained, the rutted muddy road froze so hard that the wagons could carry the obelisk to its destination. But unlike Sister West at the Grandin Press, she merely said, “Depending on what you choose to believe, some say it was coincidence and some say it was divine intervention.” With a single sentence, she draws attention to the process of sacralizing an event, making visitors conscious of the constructed nature of these narratives as she reminds us that the meaning of an event depends on one’s epistemology, not on empirical, unmediated artifacts that can supposedly speak for themselves. Madsen, too, insists that “efforts to sacralize space are efficacious only in the degree to which individuals respond personally.” He acknowledges that many Mormons do not “notice, heed, or respond” to their efforts and that some families may recode these sites differently, especially if they have a family connection to the site. He points out, however, that new converts may be “the most responsive to the Church hierarchy’s efforts to consecrate space and anchor their membership to a sacred historical geography.”

This conclusion makes a great deal of sense in that new members are the least rooted of all members. To the degree that they have conceptually or physically distanced themselves from family members, networks of friends, and even homelands, new members are in a less defined space, best described by Linenthal and Chidester as a “frontier,” for a frontier is “not a line, border, or boundary; it is a zone of intercultural contact and interchange.” Of course, rather than generating and celebrating this position of possibility, Church historical sites attempt to limit and restrict them. While frontiers are opened when two or more previously closed cultures come into contact, a “frontier zone closes when one has established hegemony.”The last thing the Church wants is an ambiguous, polyvalent site, reveling in its own multiplicity of meaning. The Church takes us by the hand and keeps us on the gravel path. We can let go, but why would we? Who is tugging on the other hand?

Dis-Membering the Past

“Would any of you like to express your feelings about the Book of Mormon?” We wait in silence, awkwardly, no doubt hoping another will respond. We seem unprepared for the question. We are tourists after all. We came to look at log homes, printing presses, barns, and a grove of trees, not to participate in a fast and testimony meeting. At last, bless her, a woman in dark slacks speaks up: “It teaches us how to live.” The comment, no matter how superficial, gets us off the hook. I want to thank her.

Of course, the missionaries have a script of sorts provided in a “site manual.” There seem to be three basic moves. Part 1 usually describes the historical context. For example, as we entered the Smith frame home in Manchester, missionaries recounted the persecution that Joseph experienced at a particular place and time. “Joseph was mocked by his friends. Mobs pursued him and would break into his home to search for the plates.”

Part 2 recontextualizes the events in a moral context. As the missionary tells the story, she explains that Joseph felt prompted to move the plates to another hiding place. Sister South concludes: “We should always be attentive to the promptings of the Spirit. If we don’t, then we may not be protected.” Part 3 completes the process for, in every case, the missionary either expresses gratitude for the plates or testifies of the truthfulness the gospel and restoration: “I know that God prepared Joseph for this work, and I’m grateful that I can be a member.” This pattern repeats itself in each room.

As we moved into the kitchen, another missionary relates how Martin Harris lost the 116 pages of the manuscript. The missionary turns this event into a moralistic tale, warning us about the need to be obedient. Finally, the missionary testifies of the importance of the work and the truthfulness of the message, inviting visitors to share their feelings about the need for prophets in these latter days.

My daughter and I encountered this process of abstraction in the Grandin Press as already mentioned. Birth and death dates were important because they suggested the presence of a divine plan operating in the present. Workmanship on the Book of Mormon testified to the divine importance of the project in the present; pirated segments of the Book of Mormon published in Abner Cole’s paper The Reflector, which he printed in Grandin’s shop on Sundays, testify to the reality of Satan’s opposition that continues today. Missionaries at the Peter Whitmer home explained that Joseph knew Oliver who knew the Whitmers, a link that became a story about “sharing the gospel with your friends” and “you never know the influence you might have on each other.” The missionaries’ testimony about the priesthood and priesthood authority uses a contemporary analogy: “Without proper authority, it would be like someone charging on your credit card without permission.”

I couldn’t help wondering if the Church site manual contains a stolen page from the Dominican monk Augustine of Dacia’s theoretical works, for medieval exegesis encourages readers to move from the literal, to the allegorical, to the moral, and finally to the anagogical, an arrival point that describes a passage in relation to the spirit of the age, or part of a world historical totality, or as part of the spiritual afterlife. Or as the conventional medieval quatrain credited to Augustine of Dacia explains, “The letter teaches events, allegory what you should believe, Morality teaches what you should do; anagogy what mark you should be aiming for.” The movement, of course, is increasingly abstract.

What do we make of this movement toward the abstract? Does it not make more sense to ground truth in a particular time and place? If not, why spend millions buying and restoring historical sites? How do we explain the appeal of the intangible, the metaphysical, the transcendent?

Against Madsen’s seemingly common-sense claim that “place does matter in establishing and maintaining a Mormon identity tied to a prophetic and sacrificial past, perhaps even more so for those Church members who have no familial link to that past,”I want to claim the opposite: To reduce the inevitable divisions in a worldwide church, to create a common identity, the Church dehistoricizes and decontextualizes its past. What I am suggesting here is that place—that log home, that grove of trees, that press— are, in fact, obstacles. Allow me to explain.

Aristotle sums it up quite neatly. He argues in his Poetics that the difference between poetry and history is that “one tells of what has happened, the other of the kinds of things that might happen. For this reason poetry is something more philosophical and more worthy of serious attention than history, for poetry speaks more of universals, history of particulars.”This attention to fundamental principles and to universals is what makes poetry so appealing to Aristotle, but the transformation also appeals to many a Mormon visitor who desires to follow the Book of Mormon prophet Nephi’s lead: “I did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning” (1 Ne. 19:23). Missionaries and visitors, in effect, translate the stories told at these sites, shifting the emphasis from the concrete to the metaphorical, from the historical to the poetic. This endowing of objects, dates, and events with spiritual significance—enough to make early Puri tan typologists proud—shifts the focus from the artifact itself to a transcendent, abstract truth.

These sister missionaries want to transform a specific event about, say, enduring false accusations, hiding plates from the mob, and allowing a friend to borrow manuscript pages, into a mythic story about the value of obedience, persistence, and faith—or their failures. The stories become myth in the sense that they offer a narrative representing the values, interests, and aspirations of the Mormon community. The stories lose their historical moorings and drift out to sea, but this portability actually makes them more useful to those seeking ethical, didactic, and timely instruction. The stories about Joseph and Moroni, golden plates and lost manuscripts, log cabins and the Burned-Over District are no longer history but poetry. But if the actual cabin, house, press, and grove are not what we encounter, then whose shores do we land upon?

We run aground upon a spiritual landscape. We drop our anchor in a pool of feeling. Madsen describes how missionaries during his visit explained that “lots of historical things happened here, but I want to focus on the spiritual things.” Another guide began by saying, “I will tell you lots of historical stuff, but I want you to remember what you’ve felt. Don’t try to remember everything I say.”Another of Madsen’s missionaries explained that “they [the missionary department leaders] changed the focus of these sites from what happened here to what it means to us.” And when I asked a missionary whether it’s odd to bear testimony to members—in essence, preaching to the choir—she explained that she hadn’t even thought about it. Her job is to bear her testimony, and that includes “perfecting the Saints.” These admonitions explain why the historical elements are largely irrelevant. To redeem a memory, one must decontextualize it, resituate it. The new conceptual landscape graces it with new meaning and significance.

I return to Madsen’s claim that the Church is “using the physical places in which Mormon history occurred to nurture the ‘geographic memory’ of Latter-day Saints, hoping to promote a common sense of identity among an increasingly diverse membership. Place does matter in establishing and maintaining a Mormon identity tied to a prophetic and sacrificial past, perhaps even more so for those Church members who have no familial link to that past.”As I try to demonstrate above, I want to argue that the exact opposite happens. Members, new or not, do not find their identity among the ruins of the past. Instead, they contemporize the past, and this act of taking an event out of its historical context is an act of redemption. When we re-member, when we reattach a lost appendage, is not this act an act of redemption? Literary scholar Terry Cochran points out that “redemption is simply the present’s opportunity to ‘indicate’ the past in a way that places a claim on the future.”In other words, the moment we bring an event to the present or the future, we redeem it. We buy it back. We reclaim it. We recover it. We possess it once again.

While we redeem an event by resituating it, there is another interesting process involved. The sacred, by definition, is that which can transcend any particular time and place. The sacred is mo bile, for the “wind bloweth where it listeth” (John 3:8). Scholars of the sacred point out that the “sacred” has to do with the act of “setting apart” a designated space. The sacred is a site “set apart from or carved out of an ‘ordinary’ environment to provide an arena for the performance of controlled, ‘extraordinary’ patterns of action.”Religious studies scholar Gerardus Van der Leeuw explains that sacred places become “transferable metaphors,” and French sociologist Henri Lefebvre adds that “abstract space” tends toward “homogeneity, towards the elimination of existing differences or peculiarities.”In sum, abstract space transcends a particular time and place and eliminates difference in the name of sameness, for sameness allows visitors to connect to others who hail from another time and place, for all are “Latter-day Saints.”

Historical figures become spiritual types as well. As latter-day prophet, Joseph becomes a Moses, a Noah, an Abraham. As a location where Joseph encountered heavenly beings, the Sacred Grove becomes the same as, say, the banks of the River Jordan or the Mount of Transfiguration. The significance of a particular time and location—Palmyra, Jerusalem, Sinai—becomes irrelevant, for they all collapse into one homogenous event: God speaks to his prophets. In this case, sacralizing a cabin, a printing press, a grove of trees, or a barn pulls them out of the historical narrative. Instead of, say, placing the tarring and feathering of Joseph in Hiram, Ohio, in the context of anti-Mormon sentiment caused by competing religious views, disdain of social class difference, fear of new settlers from the East, or fear of changing relations of power, missionaries reframe the story in spiritual terms, and by “spiritualizing” or sacralizing the place and events, these sites and experiences are liberated from a particular historical context. They become morality lessons, principles, and precepts—patterns of action—that transcend time and place. In short, the very act of setting apart a place or event allows it to circulate more freely. The sacred is born.

Walking the Labyrinth

During this same trip my daughter and I were also pilgrims of another sort. Of course, LDS Church sites are not the only sites that construct and reshape memory. The Freedom Trail, Concord and Lexington, and Plimoth Plantation all speak to national myths of American exceptionalism, justice, and industry. The Holocaust monument in Boston transforms genocide into moral responsibility, a desire for justice, and an admonition to care for our neighbors. The Emily Dickinson house celebrates a misunderstood genius, a gifted individual trapped by social conventions. I am not suggesting that every historical site functions in the same way, but a discussion of LDS historical sites should make visitors sensitive to the ways in which their experiences are mediated and packaged for them. Pilgrims should note when sites and individual people become types or abstract patterns. While I discuss sites in New York, I invite travelers to re-read their experiences in Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, Wyoming, and Utah.

To claim that a site is a kind of symbolic package or inauthentic experience does not mean that visitors are dupes, mindlessly internalizing every message. Some letters never arrive. Stamps fall off. Addresses don’t exist. And as noted earlier, guides may draw attention to the constructedness of a site. Visitors’ own experiences and interpretive frameworks may conflict with “official” versions. Critical theorist Denise Riley also reminds us that an excessive amount of repetition can ironize the simulation itself: “Say it, read it, echo it often enough and at short enough intervals . . . [and] it begins to look somewhat comical or grotesque in its isolation.”And here we arrive at a central paradox in Mormon culture: Fear of multiplicity of meaning leads to a seemingly endless repetition of the same truth claims, yet these frequent restatements draw attention to the insecurity itself, rendering what is sacred comical and grotesque. Joseph is a prophet, is a prophet, is a prophet, is a prophet. Surely there is an alternative.

Not surprisingly, geographic metaphors abound in the Bible, and Christians in particular are familiar with two kinds of paths. On the one hand, we have the “strait and narrow.” As Jesus proclaims, “Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat” (Matt. 7:13–14). Much is made of this route, and we see echoes of it in the Book of Mormon’s image of the iron rod (1 Ne. 8:20). And even in our collective culture, we associate “crooked” with deceit and lawlessness.

“To wander” suggests a lack of purpose, drifting aimlessly, holding one’s faith too loosely. In medieval Christian folklore, the “Wandering Jew” was condemned to walk the earth because he insulted Jesus on His way to Golgotha. Cain was cursed to wander the earth for killing Abel and for denying his brotherly responsibilities. The children of Israel had to wander in the wilderness for forty years because of their disobedience. Old Testament prophets and writings—the Psalms, Proverbs, Lamentations, Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Hosea in particular—are fond of using “wandering” as a metaphor for spiritual decay, stubbornness, and disobedience. Clearly, a circuitous and delayed journey manifests a wayward soul, and wandering becomes a form of damnation itself.

But an equally compelling religious symbol is the labyrinth, best exemplified on the floor of the Chartres Cathedral in France. Near the opening of the nave, often covered by wooden chairs, is a round labyrinth that is part of the stone floor itself. The circle is divided into quadrants, but the sinuous path allows one to move from section to section seamlessly as it meanders toward the destination, a six-petaled flower at the center. Writer Rebecca Solnit reminds us that, unlike mazes that are made to “perplex those who enter,” a labyrinth “has only one route, and anyone who stays with it can find the paradise of the center and retrace the route to the exit.” She reveals the key moral of these curvy paths: “Sometimes you have to turn your back on your goal to get there, sometimes you’re farthest away when you’re closest, sometimes the only way is the long one.”Like the strait and narrow path, the labyrinth has only one path that takes one to paradise—we’re not talking about wild abandonment or romping through the wilderness—but unlike the direct route, one moves about within a larger pattern, and this symbolic journey reminds us of “the complexity of any journey, the difficulty of finding and knowing one’s way,” of the need to be humble and patient, for the way “cannot be perceived as a whole all at once,” and it “unfolds in time.”Of course, we cannot deny the pleasure in the journey as we meander from place to place, gaining new perspectives and insights. Unlike the pragmatic and mechanical “straight” and narrow that ignores the route itself, reducing the scenery to distracting noise or seductive buildings, the labyrinth celebrates the journey, recognizing that the pilgrimage—the meandering, curvy, indirect path that it is—defines the purpose itself. The source of pleasure is not solely in the destination, but walking the path itself.

While we can yearn for some kind of raw, unmediated experience—a time before guides, placards, and images—we can safely tell ourselves that such a prelapsarian condition is a fantasy at best. What we can embrace, however, is time and space to reflect. I’m not surprised, then, that despite all the chatter—Mormons never miss an opportunity to hold a meeting—that our most sacred sites are largely silent and empty. While I hesitate to offer an ode to the Sacred Grove—oh, how clichéd—what I found appealing about the place was the absence of symbolic packages. Admittedly, a variety of docents have certainly packed our bags before we step into that grove. Surely we stumble under the weight of large and small packages prepared by others and ourselves. Our eyes are encased in lenses. And yet . . . and yet we encounter little else but trees, dirt, our thoughts, and maybe another person upon one of the many paths. No one is queuing up behind us. No one is telling me what to think or asking me what I feel. Yes, Joseph came to the woods alone with a question in mind, and I suspect that he might have been disappointed had he left that grove with nothing more than dirty knees. There is something heroic about his quest, and I’ve read enough Emerson and Thoreau that I can understand the desire to be a seer for others. But for some reason, I don’t need all my questions answered. I’m content to ruminate, to ponder, to turn over ideas as I would stones in my hand. I enjoy walking the labyrinth. And as my daughter and I meander through the trees—in a rainstorm, no less—laughing as we dodge huge raindrops and leap over brown puddles, I cannot help but conclude that our stroll together is the destination. We share a space, and that’s what makes the site holy.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue