Articles/Essays – Volume 52, No. 3

Imagery and Identity

“Mami, you’re light brown. I’m dark brown. And Dada is dark brown,” my two-year-old daughter blurted out unexpectedly one night before her bedtime. “Yes mama, you’re right,” I responded as my mind raced. I could not believe that my toddler could already distinguish between skin colors. Where did she learn this? Did someone tell her this at her day care?

I understood that it was likely she was just associating colors she learned in school and at home with the different skin colors of her classmates. Yet it was alarming that I hadn’t had the opportunity to introduce it to her myself. I had always imagined a grand conversation where I appropriately introduced my daughter to race, explained to her how important it was, and how she could protect her integrity and self-esteem, yet here we were. My daughter could see different skin colors, and I was the worried parent feeling completely unprepared. I started to wonder about the other connections she had made in terms of skin color. Obviously, she knew Mami was light brown, Dada was dark brown, and in a moment of humor within an otherwise serious affair, Grandma was dark-dark brown. When we watched TV, did she make any connections with the colors she saw? How about at restaurants, school, doctor visits, and more importantly to me now, church?

How could I create the appropriate framework for my daughter to see race?

I’m an immigrant. My family moved to the United States when I was very young and moved here for the same reasons many immigrants do: the chance at a better life. I am perpetually grateful for the sacrifices they made. They had to leave friends and familiar comforts to create a new path in a sometimes-hostile environment. Yet they persevered, and as a result, my life has been forever changed for the better.

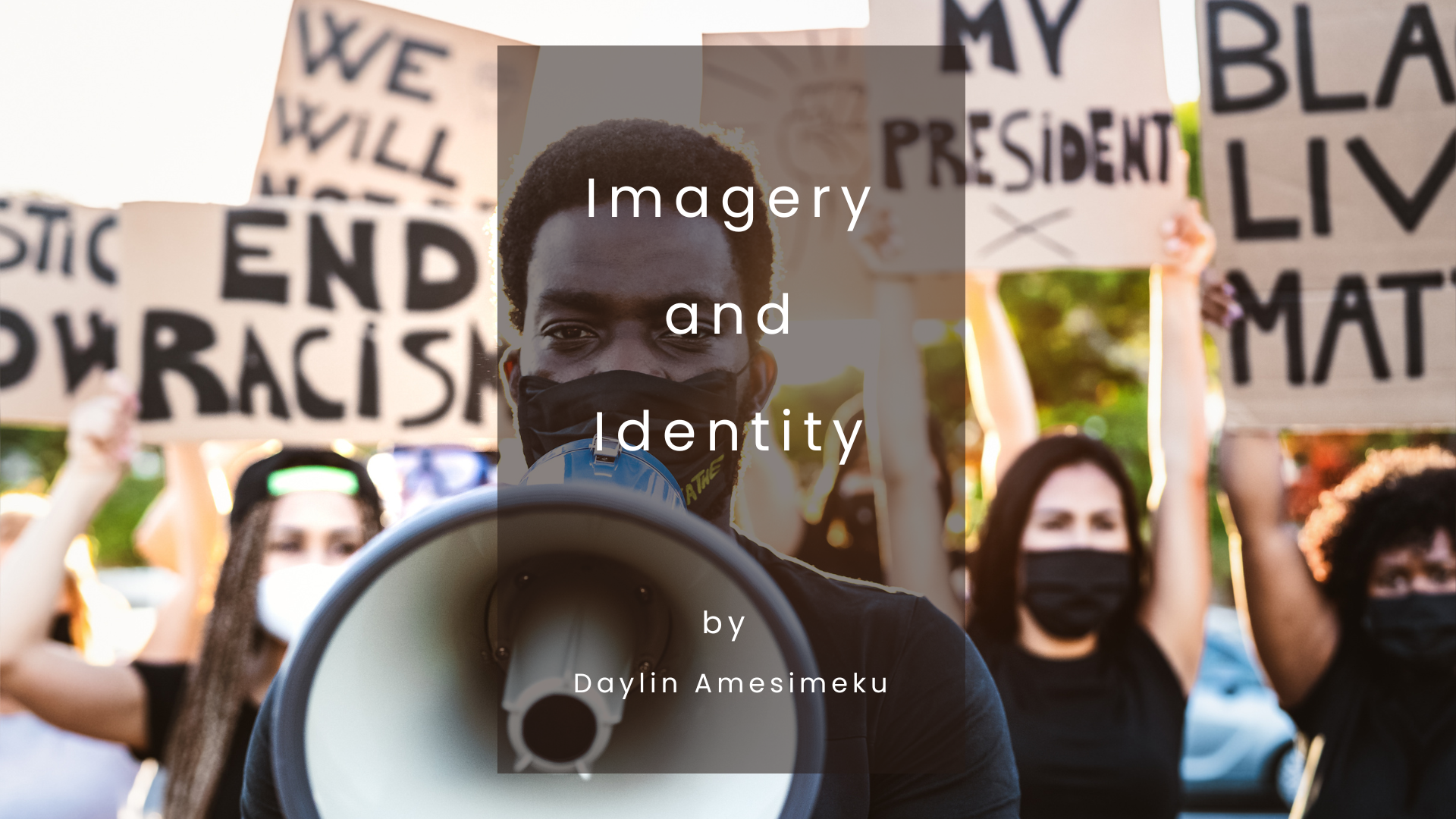

I started to understand race when I got older. Although this country afforded us a better life, it also introduced us to the disease of racism, and the United States’ long tortuous history with it. I daresay this nation’s legacy of race is the most important narrative in this country. Unfortunately, religious institutions including the LDS church were not exempt from this influence. And in my opinion the white supremacist view of race has unfortunately been present in the Church, even down to the imagery used. I had already made my peace with this, but now found myself thrown into turmoil on the realization that at such a tender age my daughter was differentiating between skin colors and internalizing it all.

A fundamental belief we members of the church share is that of deity as our father. I think as children we look for bonds and security from our parents and gain love for ourselves through those connections. If my belief is that I am a child of deity, then my connection to deity will be tied to love for myself. This realization gave me some consternation because the current image of deity was a foreigner to my little girl. And as a result, she could see herself being foreign to deity as well. If she knew she was brown, then she could obviously tell Jesus and Heavenly Father were not. And more importantly, that Jesus and Heavenly Father belong to the family of the classmates in her nursery class and not her own.

This point became even more poignant I when bought my daughter a puzzle that had a “nonconventional” Jesus—he was as dark-skinned as my husband. I gave it to her and said, “Here’s Jesus with children.” Her response was, “That’s not Jesus, that’s Dada.” It took a minute to suppress our shock, but then we explained to her that it truly was Jesus. It is important to note that we do not have any images of a “conventional” Jesus in our home. Her imagery of Jesus came strictly from her nursery class at church and visits to Grandma’s home. We also noticed how important it is to introduce alternate images to what she sees. We thought the absence of imagery would help her create her own; we now realized that we had to provide alternative imagery to what she was seeing so she could at least question it. Additionally, her calling the dark-skinned Jesus “Dada” made me realize what a filial relationship with Heavenly Father could feel like. If she could truly see Heavenly Father as her father, then should could see deity in herself, see herself and her family among the concourses of angels, and see a heaven that was made for her and those like her. As a woman and a mother, there is nothing I desire more for my daughter.

I have a testimony of the gospel of Jesus Christ, but I’m also honest enough with myself to reject specific cultural and human aspects of the Church that I do not believe are divine. White supremacy in religions, specifically in Christianity, is not unique to the LDS church. However, I do think the LDS church stands in a unique position to be everything it purports itself to be.

As I focus on what I can change, I am grateful for the small blessing of a child that has been able to communicate clearly at such a young age and taught me at my more mature age how important imagery is, and my responsibilities to her as a parent.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue