Articles/Essays – Volume 52, No. 4

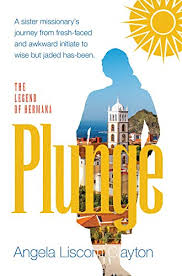

“I’m Not Shaving My Legs Until We Baptize!” | Angela Liscom Clayton, The Legend of Hermana Plunge

Deep into the narrative and mission of The Legend of Hermana Plunge, a new memoir by Angela Liscom Clayton, in a chapter focused on the consistent catcalling and unwanted advances she faced as a missionary in the Canary Islands in the late 1980s, a short retort epitomizes the first-person narrator that drives the book, Hermana Plunge. When the assistant to the president notices her unshaven legs in the car and triple takes, Hermana Plunge quickly informs him: “I’m not shaving my legs until we baptize!” (181).

This clever interjection isn’t just surprising and funny; it’s biting in its politics of gendered hypocrisy, as Hermana Plunge explains that a certain group of elders had grown out their beards under the baptism ruse. This does a good job of getting the AP to stop rubbernecking and rein in his judgement. In reality, and no one’s real business but her own, Hermana Plunge is growing out her leg hair so that she and other sister missionaries can go for their first waxing outing at a local salon on P-day, which doesn’t go as well as even the snappy comeback did.

The Legend of Hermana Plunge is an experiential, journal-informed patchwork of Angela Liscom Clayton’s proselytizing missionary experiences for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that runs chronologically from the time she receives her call while a BYU student—explaining her family’s rich missionary heritage, her upbringing in Pennsylvania, and her desire to serve in France—to her arrival in the Canaries, and her work and experiences across four different islands with ten different companions. At every turn, Clayton does well to record the pre-2012 mission era as much different than the current one, in which Women could not serve until age twenty-one or older, and notes the many instances when she felt obligated and empowered to speak and stand up to problematic, leadership-focused, entitled young men. Throughout, Clayton recollects calling for change from everyone from the mission president to the junior companions, preaching a more egalitarian missionary message of Christian love and service. Her practices prove sound and productive, and on October 22, 1989, she and Hermana Simmons witness six of their investigators attend church and get baptized in one day, earning her mission-wide fame and the nickname “Hermana Plunge.”

This unlikely transformation from Sister Liscom into Hermana Plunge is gratifying and surprising to read, especially as the author self describes early on: “I always saw myself on the fringe, not fitting in at BYU or in LDS culture. I had short hair, three earrings in each ear, and wore Suicidal Tendencies and Violent Femmes t-shirts to class. I didn’t dress or talk like people from Utah—no surprise, since I wasn’t from Utah. I hadn’t dated Mormon boys before Derek” (11). Paramount too is her individual account of what it was like to be a young, educated, unmarried woman of the faith, debating that going on a mission would put her into the “unmarriageable spinster” category, or staying would mark her as a “superficial twit.” Before the mission, she prays for a boyfriend, gets one she’s not crazy about, but has a long letter-writing relationship nonetheless until an inevitable breakup and “boyfriend bonfire.” The narrative is full of devout, chaste flirtations—in the letters, on the islands, and with other elders. These flames form and fuel a competitive and gossipy but tight-knit group of elders and sisters, who are most interested in doing the work of the Church while having fun. New friendships, food, and foreign experiences forge these young missionaries together, and Hermana Plunge learns, gaffes, loves, and leads, growing and becoming a new person in the world, guiding her to a love she’d never imagined, one the reader never would guess.

As much as it is recalled and recorded narrative, The Legend of Hermana Plunge is critique too, and immersion through the problematic gendered experiences of the mission format of the past. It is not written to be a gilded mission memoir, but a transparent and honest one, where power imbalance is called such, hypocrisies are voiced and wrestled with, and the experience of a middle-class American woman isn’t isolated from the native country, or the contemporary moments and politics that the missionaries find themselves in. The book is filled with rock songs, classic movie and book allusions, drugs and poverty and heartbreak and sickness, conversions, doubts, and hopes that all speak to and with the Canaries and their communities.

Clayton’s—or Plunge’s—own magnanimous personal insights at the end of her service are striking, and worth championing:

I found myself defending the flaws I shared, but things like leaders berating others and being egotistical were flaws I wouldn’t defend. I defended people who felt like they were on the outside, disenfranchised by the mission, but not the flawed and inadequate responses of the leaders to the rule-breakers. I was capable of empathy for those converts who broke the law of chastity, which seemed normal to me, but not to those who were too harsh in dealing with them, those who were prudish and preached a horror of the natural man. I didn’t defend laziness or dishonesty, but I detested tattling missionaries or those who pried and spied on others, considering that the greater sin. Self-justification and hypocrisy were the sins Jesus had decried, after all. But maybe all of these were also just human shortcomings. (224)

The Legend of Hermana Plunge is a rollicking, humorous, sincere look at the missionary experience, and a valuable addition to the LDS mission memoir category of faith-affirming texts. Because what is more valuable than an honest take of that impactful span of early years as told by an inspired minority counter-culture participant, replete with the universal tensions of individual friction and freedom? The memoir’s good faith is in its directness, and its good will is in the spirit of Clayton as an imperfect, effective, jaded missionary who is willing to tell it how it really happened, like it really was. As Clayton herself embraces after her first month in the mission: “I decided that the best way to deal with personal mortification was to own it and retell the stories to my fellow missionaries so they could enjoy the joke at my expense. It’s a strategy that hasn’t failed me yet” (25). Indeed, it’s a strategy that hasn’t failed her here, either.

Angela Liscom Clayton. The Legend of Hermana Plunge. Salt Lake City: By Common Consent, 2019. 211 pp. Paper: $12.95. ISBN: 978-1-948218-09-2.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue